Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The When

Transféré par

reacharunkTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The When

Transféré par

reacharunkDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

S90

THEORY OF

AIICIIITECTUKE. l)o(

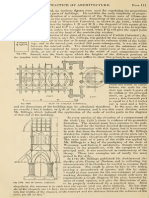

from the aiiglcb of the plan as tliore are ribs intciukd. until tluy mutually intersect each

otiier. Tlie curvatures of the ribs will be clonj^atea as they recede from the primiti\

arch, till tliey reach the centre on the place wlure the groins cross, and where of course the

flongat.d curve is a maximijm The rihs thus form, when they are of the same curvature,

portions of an inveited conoid.

1499j. In the next example

i Ji<t.

59?i/i-), the primitive arches are unequal in height, thi;

ai-ch A i)eing higher than 15 'I'he jilan remains tlie same as in that immediately preceding;

but from the inecjuality of heiglit, a d, c b, must be joined by curved lines, determined on

one side by the point a. where e a intersects th^' 1 mger arch. A curved summit rib. as

well longitudinal! V as transversely, may occur with equal or unequal heights of primitive

<rches (as in

Jig.

59'Ji.)

;

but the stellar form on the plan still remains, though diHerei.tly

niodilied, with the same, or a less or greater, number of ribs on the plan

(Jiff.

590k. ). By

truncating, as it were, the summit ribs, level or otherwise, with the tops of the primitive

arches, and introducing en tlie plan a jiolygon or a circle touching quadiants inscribed in

the square, we obtain, by means of (he rising conoidal

quadrants, figures which perform the office of a key-

stone. In this, as we have aliove observed, the con-

struction of the work is totally diff'eient from rih

vaulting, inasmuch as each course, in rising, supports

the next, after the manner of a dome, and is not de-

pendent on ribs for carrying the filling-in pieces.

Hence the distinction between fanwork and radiating

rib work so judiciously made by Mr. Willis.

1499aa. The sixth example

(Jiff-

590/.) has pri-

mitive arches of ditferent heights, forming an irre-

gular star on plan, that is to say, the points are of

different angles. The figure will scarcely need ex-

planation after what has been already said in relation

ti) the subject

I499i''. A polygonal space may be vaulted in

three different ways. First, by a central column

serving for the recejjtion of the ribs of the vault, the

:olumn or pillar performing In such case the office of a wall, as in the chapter-houses of

Worcester, Salisbury, Wells, and Lincoln. This mode evidently admits of the largest

sjiace being covered, on account of the subdivision of the whole area by means of the

Central pillar. The second mode is by a pendent for the reception of the arches, as in the

Lady Chapel at Caudebec, (given in the section Wasonrv). This mode is necess;irily re-

jtricted in practice to small spans, on account of the limits attached to the power of

materials; albeit in theory its range is as extensive as the former. The last method is by at

Fig.SOO;.

once vaulting the space from wall to wall, as in

Jiff.

590m., like the vaulting to the kitchen

of the monastery of Durham Cathidral, or.

Jiff.

.590n., similar to the chai)ter-house at York,

of which, the upper part being of wood. Ware quaintly observes,

"

The people of Yorkshire

fondly admire and justly boast of their cathedral and chapter-house. The principle of

vaulting at the chapter-house may be admired and imagined in stone; not so the vaidt of

the nave

;

it is manifestlv one of those sham productions which cheat here tl)ere is no

merit in deceiving." The principle, as Ware justly observes, is perfectly m isonie, and

might be easily carried out with stone ribs and panel stones, it being nothing more than

an extension of that exhibited in the third examjjle of simple groining

(Jiff.

590/.;

above

given; and the same remark apulies to the Durham kitchen.

I499ec We propose to offer explanations of the nature of the vaulting at King's College

Chapel at Cainbridge, and the silly story related by Walpole of Sir Christopher Wren,

raying, "that if <?ny man would show him wnere to jilacc the lir.'jt stone he would

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Rieus VaultsDocument1 pageRieus VaultsreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Piers Vaults.: When MayDocument1 pagePiers Vaults.: When MayreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- The Henry VI: (Jig. 1:516.) - Sidi?sDocument1 pageThe Henry VI: (Jig. 1:516.) - Sidi?sreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1070)Document1 pageEn (1070)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Common: Tlie TlieDocument1 pageCommon: Tlie TliereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory: Common Round WoodDocument1 pageTheory: Common Round WoodreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Arches.: ArcadesDocument1 pageArches.: ArcadesreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Of Architecture.: Dome DomeDocument1 pageOf Architecture.: Dome DomereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Now Roman: Tlie IsDocument1 pageNow Roman: Tlie IsreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Common: IklmnoDocument1 pageCommon: IklmnoreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- On Roman: ThaiDocument1 pageOn Roman: ThaireacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Piers Vaults.: Then MuchDocument1 pagePiers Vaults.: Then MuchreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1383)Document1 pageEn (1383)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory: of ArchitectureDocument1 pageTheory: of ArchitecturereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory: Its Is It IsDocument1 pageTheory: Its Is It IsreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Deem Much Xiv. AsDocument1 pageDeem Much Xiv. AsreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- This (Diet Liigher, Line Line: Is TlieDocument1 pageThis (Diet Liigher, Line Line: Is TliereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1279)Document1 pageEn (1279)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- St'ttiiig Is Ol' It Is, TlieDocument1 pageSt'ttiiig Is Ol' It Is, TliereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Where Made Much WhenDocument1 pageWhere Made Much WhenreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1026)Document1 pageEn (1026)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1283)Document1 pageEn (1283)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- London Morar MayDocument1 pageLondon Morar MayreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- May May: The Manner When TheDocument1 pageMay May: The Manner When ThereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1016)Document1 pageEn (1016)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Orders.: of of of in Englisli Feet. in FeetDocument1 pageOrders.: of of of in Englisli Feet. in FeetreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice of Architecture.: Aemfdcob GK OMDocument1 pagePractice of Architecture.: Aemfdcob GK OMreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Above DomeDocument1 pageAbove DomereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1034)Document1 pageEn (1034)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1027)Document1 pageEn (1027)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- BC HM, Nop,: Tmeolly of ArchitectureDocument1 pageBC HM, Nop,: Tmeolly of ArchitecturereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1040)Document1 pageEn (1040)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- I'Ractice: of ArchitectureDocument1 pageI'Ractice: of ArchitecturereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Architecture.: TiiicoryDocument1 pageArchitecture.: TiiicoryreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Tiieouy or Architecture.: CommonlyDocument1 pageTiieouy or Architecture.: CommonlyreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- ENDocument1 pageENreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1346)Document1 pageEn (1346)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory: of ArchitectureDocument1 pageTheory: of ArchitecturereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1063)Document1 pageEn (1063)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- EF AC EK CA DB: Ivfasonry. Then TheDocument1 pageEF AC EK CA DB: Ivfasonry. Then ThereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- The Aswân Obelisk: With some remarks on the Ancient EngineeringD'EverandThe Aswân Obelisk: With some remarks on the Ancient EngineeringPas encore d'évaluation

- Lonne: Still Is TlieDocument1 pageLonne: Still Is TliereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- '2fi5's. Is, Tlie ItsDocument1 page'2fi5's. Is, Tlie ItsreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory of the Earth With Proofs and Illustrations, Volume 2 (of 4)D'EverandTheory of the Earth With Proofs and Illustrations, Volume 2 (of 4)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tos Presentation: Submitted by Elsa Rose Roll No. 12 S1 S2 Batch ADocument23 pagesTos Presentation: Submitted by Elsa Rose Roll No. 12 S1 S2 Batch AEvin JoePas encore d'évaluation

- En (1326)Document1 pageEn (1326)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Practical Stair Building and Handrailing: By the square section and falling line systemD'EverandPractical Stair Building and Handrailing: By the square section and falling line systemPas encore d'évaluation

- Salt Lake Grotto National Speleological SocietyDocument5 pagesSalt Lake Grotto National Speleological SocietyRussell HartillPas encore d'évaluation

- We The The WeDocument1 pageWe The The WereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Literary and Structural Analysis of The First Dome On Justinian's Hagia Sophia, ConstantinopleDocument13 pagesLiterary and Structural Analysis of The First Dome On Justinian's Hagia Sophia, ConstantinopleLycophronPas encore d'évaluation

- The From MayDocument1 pageThe From MayreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory: of ArchitectureDocument1 pageTheory: of ArchitecturereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice of Architecture.: We MindDocument1 pagePractice of Architecture.: We MindreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Hi. ANH and The Many MayDocument1 pageHi. ANH and The Many MayreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Common: CarpentryDocument1 pageCommon: CarpentryreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Arcliitravp, Ivicze, Laid Latter This in inDocument1 pageArcliitravp, Ivicze, Laid Latter This in inreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1018)Document1 pageEn (1018)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- General Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsuranceDocument19 pagesGeneral Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsurancereacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1464)Document1 pageEn (1464)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1451)Document1 pageEn (1451)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1458)Document1 pageEn (1458)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1459)Document1 pageEn (1459)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocument1 pageMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1382)Document1 pageEn (1382)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocument1 pageAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1383)Document1 pageEn (1383)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- The The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesDocument1 pageThe The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesreacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1386)Document1 pageEn (1386)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1376)Document1 pageEn (1376)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1374)Document1 pageEn (1374)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- En (1372)Document1 pageEn (1372)reacharunkPas encore d'évaluation

- Okjop, E9Uweeiowuweuhjqwhjwqhhwqjdhjwjkxjasljxlassj A Short-Circuit Design Forces in Power Lines and SubstationsDocument28 pagesOkjop, E9Uweeiowuweuhjqwhjwqhhwqjdhjwjkxjasljxlassj A Short-Circuit Design Forces in Power Lines and Substationsamit77999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Design of Sanitary Sewer SystemDocument11 pagesDesign of Sanitary Sewer SystemAhmad SanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab 1aDocument6 pagesLab 1aAre NepPas encore d'évaluation

- Diseño Cercha Metalica Tipo I VerificadoDocument36 pagesDiseño Cercha Metalica Tipo I VerificadoJosé Mario Blacutt AléPas encore d'évaluation

- IS 3370 (Part 3) 1967 R 1999Document14 pagesIS 3370 (Part 3) 1967 R 1999Nayag Singh100% (1)

- Digital Signal ProcessingDocument2 pagesDigital Signal ProcessingAnonymous HyOfbJ60% (1)

- The Physics of VolleyballDocument2 pagesThe Physics of VolleyballMary Grace Arcayan LoberianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Harry G. Brittain (Ed.) - Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients, Vol. 28-Elsevier, Academic Press (2001) PDFDocument349 pagesHarry G. Brittain (Ed.) - Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients, Vol. 28-Elsevier, Academic Press (2001) PDFngochieu_909Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cse169 01Document49 pagesCse169 01hhedfiPas encore d'évaluation

- ENSC3024 Ideal Gas Lab 1Document12 pagesENSC3024 Ideal Gas Lab 1Max ShervingtonPas encore d'évaluation

- One-Factor Short-Rate Models: 4.1. Vasicek ModelDocument8 pagesOne-Factor Short-Rate Models: 4.1. Vasicek ModelbobmezzPas encore d'évaluation

- BS 300Document121 pagesBS 300Anonymous GhWU5YK8Pas encore d'évaluation

- 3 V/5 V, 450 A 16-Bit, Sigma Delta ADC AD7715 : Ma Max at 3 V SuppliesDocument32 pages3 V/5 V, 450 A 16-Bit, Sigma Delta ADC AD7715 : Ma Max at 3 V SuppliesMichele BacocchiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pirs509a BeamnrcDocument289 pagesPirs509a BeamnrcskcomhackerPas encore d'évaluation

- II B. Tech II Semester Regular Examinations April/May - 2013 Electrical Machines - IiDocument8 pagesII B. Tech II Semester Regular Examinations April/May - 2013 Electrical Machines - IiAR-TPas encore d'évaluation

- Adnan Aljarallah 1988 Kinetic of MTBE Over AmberlystDocument6 pagesAdnan Aljarallah 1988 Kinetic of MTBE Over AmberlystJason NunezPas encore d'évaluation

- Density of States - MSE 5317 PDFDocument8 pagesDensity of States - MSE 5317 PDFJohn AllenPas encore d'évaluation

- Fixed-Point Signal ProcessingDocument133 pagesFixed-Point Signal ProcessingRaveendra MoodithayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Four Bar Mechanism and Analysis in CreoDocument9 pagesFour Bar Mechanism and Analysis in CreoJigneshPas encore d'évaluation

- E Me 4076 Mechanical Vibrations T 120032004Document4 pagesE Me 4076 Mechanical Vibrations T 120032004鲁肃津Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bock LeafletDocument20 pagesBock Leaflettasos7639Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4. Translational Equilibrium and Friction.: Free-Body DiagramsDocument16 pagesChapter 4. Translational Equilibrium and Friction.: Free-Body DiagramsAlma GalvànPas encore d'évaluation

- TYPD ExercisesDocument10 pagesTYPD ExercisesConstance Lynn'da GPas encore d'évaluation

- Charles Law Strategic Intervention Material in ChemistryDocument11 pagesCharles Law Strategic Intervention Material in ChemistryDwell Joy Armada78% (9)

- Wolfson Eup3 Ch18 Test BankDocument18 pagesWolfson Eup3 Ch18 Test BankifghelpdeskPas encore d'évaluation

- Duraturf Product Group Harver Magnetic Induction: Harver Induction InfoDocument8 pagesDuraturf Product Group Harver Magnetic Induction: Harver Induction Infoadrianajones4Pas encore d'évaluation

- Incubator ReportDocument26 pagesIncubator ReportxiastellaPas encore d'évaluation

- ACI 350-06 ErrataDocument7 pagesACI 350-06 ErrataLuis Ariel B. MorilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Crystallization: A. BackgroundDocument8 pagesCrystallization: A. Backgroundchamp delacruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Shear Wall Design ReportDocument26 pagesShear Wall Design ReportAli ImranPas encore d'évaluation