Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Attitudes and Perceptions of Const Workforce On Waste

Transféré par

Citizen Kwadwo AnsongTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Attitudes and Perceptions of Const Workforce On Waste

Transféré par

Citizen Kwadwo AnsongDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Attitudes and perceptions of

construction workforce on

construction waste in Sri Lanka

Udayangani Kulatunga, Dilanthi Amaratunga and Richard Haigh

Research Institute for the Built and Human Environment, University of Salford,

Salford, UK, and

Raufdeen Rameezdeen

Department of Building Economics, Faculty of Architecture,

The University of Moratuwa, Moratuwa, Sri Lanka

Abstract

Purpose The construction industry consumes large amounts of natural resources, which are not

properly utilised owing to the generation of waste. Construction waste has challenged the performance

of the industry and its sustainable goals. The majority of the causes underlying material waste are

directly or indirectly affected by the behaviour of the construction workforce. Waste occurs on site for

a number of reasons, most of which can be prevented, particularly by changing the attitudes of the

construction workforce. Therefore, the attitudes and perceptions of the construction workforce can

inuence the generation and implementation of waste management strategies. The research reported

in this paper is based on a study aimed at evaluating the attitudes and perceptions of the construction

workforce involved during the pre- and post-contract stages towards minimising waste.

Design/methodology/approach A structured questionnaire survey was carried out to

understand and evaluate the attitudes and perceptions of the workforce. Four types of

questionnaires were prepared for project managers/site managers, supervisors, labourers, and

estimators.

Findings The ndings indicate the positive perceptions and attitudes of the construction workforce

towards minimising waste and conserving natural resources. However, a lack of effort in practising

these positive attitudes and perceptions towards waste minimisation is identied. The paper further

concludes that negative attitudes towards subordinates, attitudinal differences between different

working groups, and a lack of training to reinforce the importance of waste minimisation practices

have obstructed proper waste management practices in the industry.

Originality/value The paper reveals the effect of the attitudes and perceptions of the construction

workforce towards waste management applications, which would be of benet to construction

managers in designing and implementing better waste management practices.

Keywords Attitudes, Construction industry, Employees, Waste management, Sri Lanka

Paper type Research paper

Introduction and background to the study

Construction output is increasing rapidly in most countries, resulting in a

corresponding increase in the utilization of natural resources. Holm (1998) argues

that approximately 40 percent of the materials produced are utilized in building and

construction work. Further, the construction industry consumes 25 percent of virgin

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/1477-7835.htm

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of A.N. Hewamanage in collecting the

data for this paper.

Construction

waste in

Sri Lanka

57

Management of Environmental

Quality: An International Journal

Vol. 17 No. 1, 2006

pp. 57-72

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited

1477-7835

DOI 10.1108/14777830610639440

wood, and 40 percent of the raw stone, gravel, and sand used globally each year.

Ganesan (2000) states that materials account for the largest input into construction

activities, in the range of 50-60 percent of the total cost. In addition, a wide variety of

materials is used in the construction industry. Unfortunately, this large portion of

materials is not utilized efciently by the industry. Evidence shows that approximately

40 percent of the waste generated globally originates from the construction and

demolition of buildings (Holm, 1998) and this forms a major portion of the solid waste

discarded in landlls around the world. For instance, in the USA it is approximately 29

percent (Bossink and Brouwers, 1996) and in Australia 44 percent of landlls by mass

(McDonald, 1996).

Further, research indicates that 9 percent of the total purchased materials end up as

waste (by weight) and 1-10 percent of every single material contributes to the solid

waste stream of the site (Bossink and Brouwers, 1996). Many researchers have shown

that there is a positive correlation between waste prevention and environmental

sustainability (Federle, 1993; Lingard et al., 2001).

Construction and demolition waste have become a burden to clients, as they have

to bear the costs of waste eventually (Skoyles and Skoyles, 1987). The cost of waste

blunts the competitive edge of contractors, making their survival more difcult in a

competitive environment (Macozoma, 2002). CIRIA (1995, cited in Teo and

Loosemore, 2001) estimates that companies that produce a higher level of waste

are at a 10 percent disadvantage in tendering. Thus, Alwi et al. (2002) argue that

construction waste can signicantly affect the performance and productivity of an

organisation. Moreover, the generation of waste is a loss of prots for the contractors

due to extra overhead costs, delays and extra work in cleaning, lower productivity,

etc. (Skoyles and Skoyles, 1987).

Construction waste is also a cost to the environment that threatens its

resilience. The unavailability of dumping sites to accommodate the higher volumes

of debris from construction sites is becoming a serious problem (Chan and Fong,

2002), and a day may come when restrictions are imposed on construction waste

disposal.

The above context illustrates the problems associated with construction waste.

Improving the quality and efciency of the construction industry is highlighted by

Egan (1998), where one way of achieving this target is stated as the reduction of waste

at all stages of the construction process. Further, the report Better Public Buildings

(Department of Culture, Media and Sport, 2002) identies measuring efciency and

waste as one of the priority areas for the industry to improve its performance. Thus, it

can be seen that construction waste management has become an important area to

improve the performance of the industry in terms of economic, quality, and

sustainability aspects. Accordingly, this paper reports the ndings of a survey carried

out in Sri Lanka to evaluate the attitudes and perceptions of construction workforce

towards waste management practices. The next section describes construction waste

with particular reference to the Sri Lankan context, with a literature review on the

origins of construction waste and attitudes of construction workforce. This is followed

by the research methodology. The paper concludes with the ndings of the survey and

a discussion based on them.

MEQ

17,1

58

Construction waste

Even though there is widespread recognition across the world of the importance of

moving towards sustainability, the construction industry is notorious for producing

huge amounts of construction and demolition waste (Kwan et al., 2003). The Building

Research Establishment (1982, cited in Skoyles and Skoyles, 1987) denes construction

waste as the difference between the purchased materials and those used in a project.

According to Hong Kong Polytechnic (1993) construction waste is the by-product

generated and removed from construction, renovation and demolition work places or

sites of building and civil engineering structures. Further, construction waste has

been dened as building and site improvement materials and other solid waste

resulting from construction, re-modeling, renovation, or repair operations (Harvard

Green Campus Initiative, 2004).

Although resource optimization is one of the main objectives of any organization,

less attention is paid to construction waste minimisation even though it makes a great

contribution to the aforesaid objective. This is due to the perception regarding waste,

which has no value and which the junkman can take away (Leenders et al., 1990).

However, it can be argued that construction waste does not fall under this denition, as

it is has a residual value and is avoidable.

Construction waste in the context of the Sri Lankan construction industry

Cost of waste has a signicant impact on the Sri Lankan construction industry. Thus, a

number of studies have been carried out in this context. According to Jayawardane

(1994), concrete and mortar showed 21 and 25 percent of wastage, respectively, due to

the excess use of materials in the rectication of inaccuracies. Even though it has been

identied that minimisation of waste to a certain extent is unavoidable (Skoyles and

Skoyles, 1987), Jayawardane (1994) states that the wastage of materials in most

construction sites in Sri Lanka is beyond acceptable limits. This fact has been further

proved by a study carried out by Rameezdeen and Kulatunga (2004), as shown in

Figure 1. The box plot indicates the spread of wastages of materials and their mean

values as sand (25 percent), lime (20 percent), cement (14 percent), bricks (14 percent),

ceramic tiles (10 percent), timber (10 percent), rubble (7 percent), steel (7 percent),

cement blocks (6 percent), paint (5 percent) and asbestos sheets (3 percent).

Origins of construction waste

Construction waste stems from construction, refurbishment, and repair work, and can

emerge at any stage of a project from inception to completion. Generation of the stream

of waste is inuenced by various factors. Gavilan and Bernold (1994) classify the

causes of waste into six categories:

(1) design;

(2) procurement;

(3) handling of materials;

(4) operation;

(5) residual-related; and

(6) other.

Construction

waste in

Sri Lanka

59

As waste impairs the efciency, effectiveness, value, and protability of construction

activities, there is a need to identify the causes of waste generation and to control them

within reasonable limits. Ekanayake and Ofori (2000) classied the causes of waste

into four major categories, as shown in Table I.

The construction industry is labour-intensive. Thus, activities initiating from the

inception to completion of a project are backed up by the human component. It can be

argued that a majority of the aforementioned causes of waste are directly or indirectly

affected by the attitudes and perceptions of the personnel involved in the construction

industry. Accordingly, the human factor involved during the pre-contract stage has a

signicant inuence on the prevention of waste. Ekanayake and Ofori (2000) identied

design change during the construction project as the most signicant cause of the

generation of site waste. Awareness of waste generation factors and the attitudes of

designers can help to minimise the generation of waste that originates from the

design cause. For instance, proper identication of a clients requirements, proper

detailing of the documents, etc. can avoid most of the changes during the design stage,

thus avoiding the rework which generates waste.

Furthermore, the human factor involved during the post-contract stage can

inuence the minimisation of waste in ordering materials according to the appropriate

quantity and quality, the use of proper storage facilities, proper handling of materials,

etc. Formoso et al. (1999) argued that the lack of attention of site management to

determining waste is a major barrier for the minimisation of waste. Teo and Loosemore

(2003) highlighted the inadequate contribution of site managers to the development

and implementation of waste management plans. Further, research has shown that the

attitudes of construction labourers towards waste minimisation activities are negative

(Formoso et al., 1999; Alwi et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Box plot for wastage of

materials

MEQ

17,1

60

In the Sri Lankan context, it has been identied that cutting and management are the

most signicant causes of waste (Rameezdeen and Kulatunga, 2004). Therefore it is

argued that in any waste prevention programme, cutting and management waste

should be given priority over other causes by means of design interventions (such as

dimensional coordination) and by providing adequate supervision and proper

organization of site activities to avoid design and management waste, respectively.

The above discussion highlights the relationship between the attitudes and

perceptions of the construction workforce and the generation of waste. Skoyles and

Skoyles (1987) suggest that waste occurs on site for a number of reasons, most of

which can be prevented, particularly by changing attitudes. Accordingly, this study is

focused on identifying the attitudes and perceptions of the construction workforce

during the pre- and post-contract stages. The following section discusses the attitudes

and perceptions of the construction workforce.

Attitudes of the construction workforce

Attitudes

Attitudes are an important concept in helping people to understand their social world.

They help us to dene how we perceive and think about others, as well as how we

behave towards them (Wayne State University, 2004).

Design Lack of attention paid to dimensional co-ordination of products

Changes made to the design while construction is in progress

Designers inexperience in method and sequence of construction

Lack of attention paid to standard sizes available on the market

Designers unfamiliarity with alternative products

Complexity of detail in drawings

Errors in contract documents

Incomplete contract documents at commencement of project

Selection of low-quality products

Operational Errors by tradespersons or labourers

Accidents due to negligence

Damage to work done caused by subsequent trades

Use of incorrect material, thus requiring replacement

Required quantity unclear due to improper planning

Delays in passing information to the contractor on types and sizes of products to

be used

Equipment malfunctioning

Inclement weather

Material handling Damages during transportation

Inappropriate storage leading to damage or deterioration

Materials supplied in loose form

Use of materials which are closed to working place

Unfriendly attitude of project team and labourers

Theft

Procurement Ordering errors

Lack of possibilities to order small quantities

Purchased products that do not comply with specication

Source: Ekanayake and Ofori (2000)

Table I.

Sources and causes of

construction waste

Construction

waste in

Sri Lanka

61

Judd et al. (1991; cited in Wayne State University, 2004) dene attitudes as the

evaluation of various objects that are stored in memory. In a simpler manner, an

attitude can be dened as a psychological tendency to evaluate a particular object or

situation in a favourable or unfavourable way, which causes someone to behave in a

certain way towards it (Ajzen, 1993; cited in Teo and Loosemore, 2003). This was

further supported by Teo and Loosemore (2003), who emphasised the importance of

attitudes to those who hold them, as they help people to categorise, structure and

prioritise the world around them. Thus, attitudes are important to managers as they

determine peoples behaviour and provide an insight into their motivating values and

beliefs. According to the tri-component model (Table II), an attitude includes affect

(feeling), cognition (thought), and behaviour (Spooncer, 1992).

There are basically two schools of thoughts regarding the development of attitudes

(Wayne State University, 2004):

(1) By changing the environment Some people say that matters are arranged so

that people have to behave in a certain manner, eventually their attitudes will

change in line with that way. For example, re-use of materials can be made a

rule on site.

(2) By changing attitudes In the second school of thought, it is said that if one

could change peoples attitudes, their behaviour would change accordingly. For

example, the importance of waste management practices can be conveyed to

employees.

In practice, considering both points of view is signicant, i.e. reuse of materials should

be made a rule as well as better knowledge being given to employees regarding the

importance of waste management practices.

In terms of the formation of attitudes, ve steps can be listed as part of the process

(Spooncer, 1992):

(1) Knowledge of the correct procedures and the ability to carry them out.

(2) Knowledge of the reasons behind the correct procedures and practices.

(3) Examples set by managers, sometimes called the culture of the organisation

or the way we do things here.

(4) The reinforcement of important messages.

(5) Support of these attitudes through the procedures and reward systems of the

organisation.

This highlights the importance of attitudes in the social environment and the inuence

that attitudes can have on human behaviour. Further, it identies the possible ways

Component Characteristics

Affect Emotional reactions

Cognition Internalised mental representations, beliefs, thoughts

Behaviour The tendency to respond or overtly act in a

particular way

Table II.

Components of attitudes

MEQ

17,1

62

and means of developing and changing human attitudes by applying certain

approaches. Accordingly, the following section discusses the attitudes and perceptions

of the construction workforce.

Attitudes and perceptions of the construction workforce

Waste has been accepted as an inevitable by-product, with a strong belief that waste

reduction activities will not be able to eliminate the generation of waste completely

(Teo and Loosemore, 2001). These negative perceptions are the main barriers to

effective waste management.

As the construction industry is labour-intensive, the attitudes and perceptions of

people inuence its growth. This fact is unquestionably true for the generation

and controlling of waste. The importance of attitudes in waste management was

identied by Hussey and Skoyles as early as 1974, when they asserted that it is a

change in this attitude rather than a change in technique which is likely to have

most effect overall (Hussey and Skoyles, 1974). Teo and Loosemore (2001) found

that attitudes towards waste reduction have become one of the reasons behind the

difculties of the management of waste in the construction industry. Loosemore

et al. (2002) and Skoyles and Skoyles (1987) highlight the importance of human

factors in the minimisation of waste, and argue that waste can be prevented by

changing peoples attitudes. However, according to Skoyles and Skoyles (1987,

cited in Teo and Loosemore, 2001), the involvement of people is being ignored in

the waste management equation.

The structure of the construction industry itself inuences the attitudes of the

people involved in it. For example, the construction industry rewards fast workers

and bonuses are paid for early completion (Teo and Loosemore, 2001). Thus the

attitudes of people are formed in such a way as to obtain rewards even by

foregoing waste management practices. Further, due to the high involvement of

subcontractors in projects for a shorter period, adaptation of procedures cannot be

identied. For example, Jayawardane (1994) found that the wastage of materials by

subcontract labour is higher than that by direct labour.

For the successful implementation of waste management measures on a project,

collective effort and responsibility from all parties involved in it is important.

According to Teo and Loosemore (2001), attitudes regarding waste differ from one

organization to another, depending on their culture and waste management

policies. In addition, various occupational groups have different attitudes towards

the generation and control of waste (Teo and Loosemore, 2001).

The above arguments support the view that the waste generated by construction is

not something to be ignored and the attitudes of the people involved in the industry

play a major role in controlling waste. Graham and Smithers (1996) state that for

successful waste management practices, interdisciplinary approaches between all

stakeholders are essential. Therefore, by identifying the attitudes and perceptions of

the construction workforce, areas that require special attention can be identied,

leading to the identication of better waste management practices. In the Sri Lankan

context, research is limited in this area; thus, this study is aimed at identifying the

attitudes and perceptions of different individuals at pre- and post-construction stages

in the Sri Lankan construction industry. Accordingly, the following section briey

Construction

waste in

Sri Lanka

63

identies the specic aims and objectives of this study, followed by the research

methodology adopted.

Aims and objectives and research methodology

Aims and objectives

The principal aim of the study is to identify the attitudes and inuence of the

construction workforce during pre- and post-contract stages towards waste

management practices in the Sri Lankan construction industry. To achieve this aim,

the following objectives were formulated:

.

to identify the attitudes of contractors during the pre-contract stage (estimators)

towards construction waste management practices on various issues;

.

to identify the attitudes of different levels of employees of contractor

organisations (site managers, supervisors, skilled and unskilled labourers)

regarding issues pertaining to construction waste management practices;

.

to compare and contrast the differential attitudes of employees at the

pre-construction stage with employees at the post-construction stage; and

.

to identify the possible ways of developing waste management practices within

the construction industry.

Research methodology

A structured questionnaire survey was carried out to understand and evaluate the

attitudes and perceptions of the workforce. The sample for the questionnaire survey

was selected from building contractors in the Sri Lankan construction industry. Four

types of questionnaires were prepared for project managers/site managers,

supervisors, labourers and estimators. The sample of the questionnaire survey is

shown in Table III.

Results and discussion

Likert scales are commonly used in attitudinal measurements (Ryerson University,

2004). Since this research is also focused on ascertaining the attitudes of the

construction workforce, the questionnaires were prepared based on the Likert scale

with a ve-point scale ranging from strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor

disagree, disagree, to strongly disagree. Data is analysed using the median and

mode of the results where appropriate. Data gathered through the questionnaires leads

to the following ndings.

Category

Number of

questionnaires

issued

Number of

respondents

Percentage

response

Estimators 24 20 83

Project managers/site managers 55 55 100

Supervisors 107 107 100

Workers 586 586 100

Table III.

Sample of the

questionnaire survey

MEQ

17,1

64

Perception of contractors during the pre-construction stage

In a construction organization, the estimator plays a major role, as he/she is the key

person who is responsible for success in securing contracts. According to the data

collected, 55 percent of estimators presumed that their organisations performed well in

the area of waste management, while 30 and 15 percent stated their response as

disagree and not sure, respectively. Despite this, 75 percent of estimators believed

that the cost of waste severely affects the cost of projects. However, the perception of 95

percent of estimators is that wastage of materials is unavoidable. A majority of the

estimators state that waste management strategies do not exist in their organisations,

as shown in Figure 2.

During the estimating process, there is an allowance for waste to compensate the

cost of waste during the construction stage. Unfortunately, the results of the survey did

not support this argument. It can be clearly seen from Figure 3 that the amounts

obtained from the actual waste are greater than the waste allowances at the

pre-construction stage. Thus, it can be argued that most contractors are unable to

recover the loss arising due to wastage of materials.

Figure 3.

Difference between actual

waste and the wastage

allowances made during

the pre-construction stage

Figure 2.

Responses of estimators

regarding company

performance towards

waste, knowledge of

existing strategy and

effect of cost of waste

Construction

waste in

Sri Lanka

65

Further, the research identied that 75 percent of estimators agreed that actual

wastage is higher than the allowance they consider at the pre-construction stage. The

competitive nature of the industry (65 percent) and the unavailability of actual data

from previous projects (75 percent) have prevented them from using actual amounts in

their tenders.

The lack of attention to the material waste allowances was further proven by the

ranks given by the estimators to their priorities at the pre-construction stage. Table IV

clearly shows that prots and overheads of the project govern estimators priorities,

while they pay least attention to construction wastage allowances. Thus, during the

pre-construction stage less attention is paid to construction waste, and more priority is

given to other bidding strategies.

Estimators apply various mechanisms to build up the norm for material wastage

allowances. This research revealed that past experience and norms in the Building

Schedule of Rates are used by the majority of estimators, while about 30 percent go for

work studies. Even though frequent updating is essential to build up reliable norms, a

lack of data ow from construction sites to estimators was identied, which impairs

the knowledge of estimators regarding actual material wastage.

Perceptions of contractors during the post-contract stage

It is during the post-contract stage that waste-controlling tools and management

strategies are actually implemented. Thus, the attitudes and perceptions of the

personnel involved during the post-contract stage are vital for effective waste

management.

Almost all the personnel that responded agreed that natural resources should be

conserved, (100 percent agreement from both managers and supervisors, and 99

percent agreement from workers). This indicates that all the respondents have a

positive perception regarding the degradation natural resources and the importance of

preserving them.

As discussed earlier, for the development of attitudes and the environment of the

organisation can be arranged in such a way as to direct the behaviours of people in a

certain manner. For example, organisational strategies and company policies can be

introduced to inuence workers attitudes in positive directions. To comply with this,

knowledge regarding the existence of a waste management strategy in the

organisation was evaluated (Figure 4). Supervisors have the highest positive

perception regarding this, followed by managers. However, workers knowledge of

such strategies is comparatively low only 10 percent of them strongly agreed with

this fact. Further, 19 percent of workers were not sure about this. This shows the

Factor Rank

Prot 1

Overheads of the project 2

Location 3

Type of client 4

Contingencies 5

Waste allowance 6

Table IV.

Priorities at the

pre-construction stage

MEQ

17,1

66

different awarenesses of various working groups regarding the environment or the

culture of the organisation. Further, understanding of the organisational strategies

diminishes from the top to the bottom of the hierarchy. In addition, this gives a better

picture of communication standards within the organisation. Due to a lack of

awareness of such strategies, workers do not accept them as explicit activities in

organisations. Thus, it can be suggested that as construction workers are the ultimate

handlers of construction materials, the optimum usage of such strategies cannot be

achieved.

To establish waste management practices within all the levels of working groups in

an organization, proper recognition should be given and it should be incorporated

within all other operations on the site (Cole, 2000). The importance given by different

personnel to waste management was assessed as part of this survey. Although the

overall attitude to the importance of waste management is highly positive in all the

working groups, the attention paid to waste management in actual practice is not so

apparent, as highlighted in Figure 5. This may be due to the lack of time devoted to

waste management practices in the real-life context. It can also be identied that

Figure 4.

Existence of waste

management strategy

Figure 5.

Importance of waste

management

Construction

waste in

Sri Lanka

67

labourers gave the least attention to waste management practices. The reason behind

this is suggested to be the time constraints of the construction industry and the lack of

benets gained by such practices. From the perspective of labourers, few personal

benets are gained by adopting waste management practices. As construction work is

organised in a way to reward fast workers, and in most of circumstances payments are

made on piece rate basis, tradesmen are more ready to use a fresh piece of material

rather than spending little more time with cut pieces.

When managers were asked to rank the perceived barriers to the implementation of

waste management principles, attitudes of people and difculty in changing existing

work practices were identied as the main barriers, while cost ineffectiveness was

identied as the barrier that had the least impact (Table V).

When implementing a strategy and moving towards a specic target, a better

understanding between the parties involved is important. Negative attitudes and lack

of condence may not yield the maximum benets. According to the research reported

in this paper, the majority of supervisors and workers believe that their management

and co-workers have a positive perception regarding the importance of construction

waste management. In contrast, the management of the organizations do not have a

good perception regarding workers attitudes. Table V further highlights this fact, as

the majority of the managers believe that the main barrier to better waste management

are the attitudes of workers. This shows the negative attitudes of managers towards

their workers and the positive attitudes of workers towards their managers. In such a

situation, the effectiveness of the managerial functions will not come in to practice

properly due to the lack of condence between parties.

As discussed earlier, ve steps are involved in the formation of positive attitudes

within an organisation or in making people behave in a certain way. Two of these are

providing knowledge about correct procedures and the reinforcement of important

messages. This can be done mainly through the implementation of training

programmes. Hence, the level of training and knowledge provided to workers about the

consequences and opportunity costs of wasteful practices can inuence their attitudes

towards waste management practices. Forty-two and 60 percent of supervisors and

labourers, respectively, answered that waste management applications were not

included in their training sessions. This indicates a lack of knowledge and

Barrier Rank

Attitudes of the workers cannot be changed 1

Difculty in changing existing work practices 2

There is no stated company policy on waste management 3

Lack of industry norms 4

Time-consuming (rather than reusing a broken brick, it is easier to use a new one) 5

There is no incentive to manage waste 6

Requires more personnel 7

It is not perceived as part of the managers job 8

Waste management is not cost-effective 9

Table V.

Barriers to waste

management practices

MEQ

17,1

68

reinforcement of ideas to the workforce regarding the importance of waste

management practices.

Even though 98 percent of managers identied waste management as being as

important as other site activities (Figure 5), the least priority was given to waste

management in actual practice, whereas the highest priority was given to monitoring

quality, followed by progress and cost factors (Table VI).

Comparison of attitudes of construction estimators and contractors

A difference in the perception of estimators and site managers was identied relating

to the performance of organisations in the area of waste management (Figure 6). The

majority of site managers (85 percent) believe that their organisations perform well in

the area of waste management, while only 55 percent of estimators believe this.

However, only 45 percent of site managers and 60 percent of estimators believe that

their company has a waste management strategy.

This indicates the differences in attitudes and perceptions of different groups of

people within the same organisation, one group having a negative perception and the

other having a positive perception regarding the performance of waste management

applications and the existence of an associated company policy. Therefore it can be

Activity Rank

Monitoring the quality of work 1

Monitoring the progress of work 2

Cost control 2

Assessing the resource requirements, procurement and incorporating them in the work 4

Safety management 5

Holding site meetings to discuss issues and problems 6

Waste management 7

Table VI.

Priorities of site activities

Figure 6.

Comparison of perceptions

of estimators and site

managers

Construction

waste in

Sri Lanka

69

argued that these contradictory perceptions negatively inuence effective waste

management practices at the organization level.

Conclusion

Minimisation of construction waste has been emphasised in terms of improving

performance while achieving the sustainable goals of the industry. Since the

construction industry is labour-intensive, the attitudes and perceptions of the

workforce affect its growth, and minimisation of waste is not an exception. Therefore, a

change in the attitudes and perceptions of the construction workforce is vital to gain

the maximum benets from waste management practices. Thus, this research has

focused on the Sri Lanka construction workforce to evaluate and identify the inuence

of their attitudes and perceptions on waste management strategies. The research

reported in this paper indicates the positive perceptions and attitudes of the

construction workforce towards minimising waste and conserving natural resources.

However, the behaviour of construction workforce in the actual scenario indicates a

lack of effort in practising their positive attitudes and perceptions towards waste

minimisation. The reasons behind this lack of practice of waste management

applications were found to be other priorities during the pre- and post-construction

stages, such as prot, time, cost, etc.

It can also be concluded that negative attitudes towards subordinates, attitudinal

differences between different working groups, and a lack of training to reinforce the

importance of waste minimisation practices have obstructed proper waste

management practices in the construction industry. Further, inadequate

communication of strategies from the top level to the bottom level of the

organisation, and a lack of data ow from construction sites to estimators, have

negatively affected waste management applications. Thus, the development of better

communication channels within the organisation, the use of reliable practices (work

studies) to establish waste allowances, providing proper training to the construction

workforce regarding waste management practices, and introducing incentives for

better waste management practices would help to develop and implement waste

management applications in the construction industry and thereby improve its

performance.

References

Alwi, S., Hampson, K. and Mohamed, S. (2002), Waste in the Indonesian construction projects,

Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Creating a Sustainable Construction

Industry in Developing Countries, November 11-13, Stellenbosch, pp. 305-15.

Bossink, B.A.G. and Brouwers, H.J.H. (1996), Construction waste: quantication and source

evaluation, Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 122 No. 1, pp. 55-60.

Chan, H.C.Y. and Fong, W.F.K. (2002), Management of construction and demolition materials

and development of recycling facility in Hong Kong, Proceedings of the International

Conference on Innovation and Sustainable Development of Civil Engineering in the 21st

Century, Beijing, pp. 172-5.

Cole, R.J. (2000), Building environmental assessment methods: assessing construction

practices, Construction Management and Economics, Vol. 18 No. 8, pp. 949-57.

MEQ

17,1

70

Department of Culture, Media and Sport (2002), Better Public Buildings, Department of Culture,

Media and Sport, London.

Egan, J. (1998), Rethinking Construction: Report from the Construction Task Force, Department

of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, London.

Ekanayake, L.L. and Ofori, G. (2000), Construction material waste source evaluation,

Proceedings of Strategies for a Sustainable Built Environment, Pretoria, August 2,

available at: www.sustainablesettlement.co.za/event/SSBE/Proceedings/ekanyake.pdf

Federle, M.O. (1993), Overview of building construction waste and its potential for materials

recycling, Building Research Journal, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 31-7.

Formoso, T.C., Hirota, E.H. and Isatto, E.L. (1999), Method for waste control in the building

industry, available at: http://construction.berkeley.edu/,tommelein/IGLC-PDF/

Formoso&Isatto&Hirota.pdf

Ganesan, S. (2000), Employment, Technology and Construction Development, Ashgate Publishing

Company, Aldershot.

Gavilan, R.M. and Bernold, L.E. (1994), Source evaluation of solid waste in building

construction, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 120 No. 3,

pp. 536-52.

Graham, P.M. and Smithers, G. (1996), Construction waste minimization for Australian

residential development, Asia Pacic Building and Construction Management Journal,

Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 14-19.

Harvard Green Campus Initiative (2005), Construction waste management, available at: http://

216.239.59.104/search?q=cache:KDlWMburqfUJ:www.greencampus.harvard.edu/hpbs/

documents/CDWaste.pdf %22construction waste%22 and denitions&hl=en

Holm, F.H. (1998), Ad Hoc Committee on Sustainable Building, Norwegian Building Research

Institute, Blinderm.

Hong Kong Polytechnic (1993), Reduction of Construction Waste: Final Report, The Hong Kong

Construction Association, Hong Kong.

Hussey, H.J. and Skoyles, E.R. (1974), Wastage of materials, Building, Vol. 22, February,

pp. 91-4.

Jayawardane, A.K.W. (1994), Are we aware of the extent of wastage on our building

construction sites?, Engineer, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 41-5.

Kwan, M.M.C., Wong, E.O.W. and Yip, R.C.P. (2003), Cultivating sustainable construction waste

management, Journal of Building and Construction Management, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 19-23.

Leenders, M.R., Fearon, H.E. and England, W.B. (1990), Purchasing and Management, Irwin,

Homewood, IL.

Lingard, H., Gilbert, G. and Graham, P. (2001), Improving solid waste reduction and recycling

performance using goal setting and feedback, Construction Management and Economics,

Vol. 19 No. 8, pp. 809-17.

Loosemore, M., Lingard, H. and Teo, M.M.M. (2002), In conict with nature waste

management in the construction industry, in Best, R. and Valance, G. (Eds), Post Design

Issues Innovation in Construction, Arnold, London, pp. 256-76.

McDonald, B. (1996), RECON waste minimization and environmental programme, Proceedings

of the CIB TG16 Commission Meeting and Presenataions, RMIT, Melbourne.

Construction

waste in

Sri Lanka

71

Macozoma, D.S. (2002), Construction site waste management and minimisation: international

report, International Council for Research and Innovation in Buildings, Rotterdam,

available at: www.cibworld.nl/pages/begin/Pub278/06Construction.pdf

Rameezdeen, R. and Kulatunga, U. (2004), Material wastage in construction sites: identication

of major causes, Journal of Built-Environment Sri Lanka, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 35-41.

Ryerson University (2004), Ordinal scale, available at: www.ryerson.ca/,mjoppe/

ResearchProcess/741process10a2.htm

Skoyles, E.R. and Skoyles, J.R. (1987), Waste Prevention on Site, Mitchell Publishing, London.

Spooncer, F. (1992), Behavioural Studies for Marketing and Business, Stanley Thornes,

Leckhampton.

Teo, M.M.M. and Loosemore, M. (2001), A theory of waste behavior in the construction

industry, Construction Management and Economics, Vol. 19 No. 7, pp. 741-9.

Teo, M.M.M. and Loosemore, M. (2003), Changing the environmental culture of the construction

industry, paper presented at the ASCE Construction Research Congress Conference,

University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, pp. 345-76.

Wayne State University (2004), Attitude, Detroit, MI, available at: http://sun.science.wayne.

edu/,wpoff/cor/grp/change.html

Corresponding author

Udayangani Kulatunga can be contacted at U.Kulatunga@salford.ac.uk

MEQ

17,1

72

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com

Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hydropower Best PracticeDocument14 pagesHydropower Best PracticeCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Improving Construction ProductivityDocument56 pagesImproving Construction ProductivitychienthangdoPas encore d'évaluation

- Discusion Board 2 - Reform MovementsDocument4 pagesDiscusion Board 2 - Reform MovementsCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Assistance To Cooperation During The BLDG Const StageDocument10 pagesAssistance To Cooperation During The BLDG Const StageCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- AGC Guide To Construction Financing 2nd EditionDocument26 pagesAGC Guide To Construction Financing 2nd EditionCitizen Kwadwo Ansong100% (1)

- What Is Lean Construction?Document54 pagesWhat Is Lean Construction?Citizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Cash FlowDocument146 pagesCash FlowCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Discusion Board 2 - Reform MovementsDocument4 pagesDiscusion Board 2 - Reform MovementsCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection 2 - Who Should Be Allowed To VoteDocument4 pagesReflection 2 - Who Should Be Allowed To VoteCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Defining Distance LearningDocument14 pagesDefining Distance LearningCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- The Evolution of American Voting Rights in 242 Years Shows How Far We, Panetta and Reaney, 2015Document15 pagesThe Evolution of American Voting Rights in 242 Years Shows How Far We, Panetta and Reaney, 2015Citizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection 1 - How Should Society Balance The Need For Tolerance With The Need To Protect ItselfDocument5 pagesReflection 1 - How Should Society Balance The Need For Tolerance With The Need To Protect ItselfCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection 4 - Where Does A Nation's Identity Come FromDocument3 pagesReflection 4 - Where Does A Nation's Identity Come FromCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Motivations For Environmental Collaboration Within The Building and Construction IndustryDocument34 pagesMotivations For Environmental Collaboration Within The Building and Construction IndustryCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- The Factors Affecting Construction Performance in Ghana: The Perspective of Small-Scale Building ContractorsDocument8 pagesThe Factors Affecting Construction Performance in Ghana: The Perspective of Small-Scale Building ContractorsCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- 27 Minutes 18Document95 pages27 Minutes 18Citizen Kwadwo Ansong100% (2)

- Differing Perspectives On Collaboration I ConstDocument16 pagesDiffering Perspectives On Collaboration I ConstCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Contractor Practices For Managing Extended Supply Chain Tiers - SCM-04-2013-0142Document5 pagesContractor Practices For Managing Extended Supply Chain Tiers - SCM-04-2013-0142Citizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Pink Form - 1988 EditionDocument24 pagesPink Form - 1988 EditionCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Improving Construction Supply Chain An CollaborationDocument12 pagesImproving Construction Supply Chain An CollaborationCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing Maturity Development of Purchasing Management in ConstructionDocument44 pagesAssessing Maturity Development of Purchasing Management in ConstructionCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of A Hybrid Ultrasonic and Optical Sensing For Precision LinearDocument15 pagesDevelopment of A Hybrid Ultrasonic and Optical Sensing For Precision LinearCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Management Practices in The Ghanaian House Building IndustryDocument14 pagesManagement Practices in The Ghanaian House Building IndustryCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Project Management Practices in Public Sector in West Bank Ministry of Public Works HousingDocument163 pagesAnalysis of Project Management Practices in Public Sector in West Bank Ministry of Public Works HousingCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- An Optimal Target Cost Contract Witha Risk Neutral OwnerDocument20 pagesAn Optimal Target Cost Contract Witha Risk Neutral OwnerCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Equitable Risks Allocation of Projects Inside China-Analyses From Dephi Survey StudiesDocument15 pagesEquitable Risks Allocation of Projects Inside China-Analyses From Dephi Survey StudiesCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Risk Criticality and Allocation in Privatised Water Supply Projects in Indonesia by WibowoDocument27 pagesRisk Criticality and Allocation in Privatised Water Supply Projects in Indonesia by WibowoCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- PhysicsLAB - Period of A PendulumDocument3 pagesPhysicsLAB - Period of A PendulumCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument11 pagesAdvantages and DisadvantagesFaizan Fathizan100% (1)

- Allocating Vendor Risks in The Hanford Waste CleanupDocument12 pagesAllocating Vendor Risks in The Hanford Waste CleanupCitizen Kwadwo AnsongPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

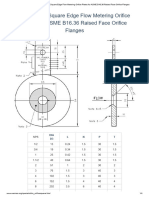

- Wermac - Dimensions of Square Edge Flow Metering Orifice Plates For ASME B16.36 Raised Face Orifice FlangesDocument4 pagesWermac - Dimensions of Square Edge Flow Metering Orifice Plates For ASME B16.36 Raised Face Orifice Flangestechnicalei sulfindoPas encore d'évaluation

- ExtruderDocument104 pagesExtruderAnuj Gupta80% (5)

- Oertli - SculeDocument307 pagesOertli - SculeDore EmilPas encore d'évaluation

- Sofia ShewaregaDocument1 pageSofia ShewaregafiliPas encore d'évaluation

- Aliens Colonial Marines ManualoptimizationguideDocument4 pagesAliens Colonial Marines ManualoptimizationguideMax LuxPas encore d'évaluation

- Abap RicefwDocument2 pagesAbap RicefwSchatenz ZnetahcsPas encore d'évaluation

- Creed Corporation Is Considering Manufacturing A New Engine Designated As PDFDocument2 pagesCreed Corporation Is Considering Manufacturing A New Engine Designated As PDFDoreenPas encore d'évaluation

- TMC 2007 Technical BackgroundDocument27 pagesTMC 2007 Technical Backgroundluigi_mattoPas encore d'évaluation

- Irshad Ansari: Al Raha Village Mafraq Abu Dhabi UAEDocument2 pagesIrshad Ansari: Al Raha Village Mafraq Abu Dhabi UAEirshadPas encore d'évaluation

- TR CD 04e - Compex Ex01 04Document1 pageTR CD 04e - Compex Ex01 04Ullas KrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Ahmed Madad Proposal NormalDocument29 pagesAhmed Madad Proposal NormalDhaabar Salaax100% (1)

- Skil Router 1830 ManualDocument136 pagesSkil Router 1830 Manualrorcacho100% (1)

- UNITROL Expert Days 2017 Switzerland PDFDocument1 pageUNITROL Expert Days 2017 Switzerland PDFmringkelPas encore d'évaluation

- SGL Carbon - Graphite HeDocument28 pagesSGL Carbon - Graphite HevenkateaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lean Think PDFDocument13 pagesLean Think PDFசரவணகுமார் மாரியப்பன்Pas encore d'évaluation

- Applying eTOM (Enhanced Telecom Operations Map) Framework To Non-Telecommunications Service Companies - An Product/Service/Solution Innovation ExampleDocument45 pagesApplying eTOM (Enhanced Telecom Operations Map) Framework To Non-Telecommunications Service Companies - An Product/Service/Solution Innovation ExampleorigigiPas encore d'évaluation

- 4maint MGMT BIE2004 Wk4 2023Document39 pages4maint MGMT BIE2004 Wk4 2023aimanfznnnPas encore d'évaluation

- RENK Coupling Solutions enDocument182 pagesRENK Coupling Solutions enhumayun121Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Operations ManagementDocument40 pagesIntroduction To Operations ManagementDanielGómezPas encore d'évaluation

- Project SQLDocument5 pagesProject SQLHazaratAliPas encore d'évaluation

- Powder Actuated ToolsDocument1 pagePowder Actuated ToolsJayvee Baradas ValdezPas encore d'évaluation

- VCTDS-03143-En Sea Water Valve PU 2192Document8 pagesVCTDS-03143-En Sea Water Valve PU 2192TimPas encore d'évaluation

- Flexible Rolling of Aluminium Alloy Sheet - Process Optimization and Control of Materials Properties PDFDocument26 pagesFlexible Rolling of Aluminium Alloy Sheet - Process Optimization and Control of Materials Properties PDFAnderssonChitivaPas encore d'évaluation

- EX2100 Excitation SystemDocument26 pagesEX2100 Excitation SystemJeziel Juárez100% (2)

- As 1172.2-1999 Water Closet (WC) Pans of 6 3 L Capacity or Proven Equivalent CisternsDocument7 pagesAs 1172.2-1999 Water Closet (WC) Pans of 6 3 L Capacity or Proven Equivalent CisternsSAI Global - APACPas encore d'évaluation

- Steven Paul JobsDocument2 pagesSteven Paul JobsBharath SriramPas encore d'évaluation

- Clamp Ring Closures: Sizes: 4-Inch and LargerDocument4 pagesClamp Ring Closures: Sizes: 4-Inch and LargerFilipPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 Enystar enDocument74 pages05 Enystar enAnonymous BBX2E87aHPas encore d'évaluation

- HYPERGROWTH by David Cancel PDFDocument76 pagesHYPERGROWTH by David Cancel PDFAde Trisna100% (1)

- Jurnal e CommerceDocument8 pagesJurnal e Commercewawan_goodPas encore d'évaluation