Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Arab Spring

Transféré par

Javeriarehan0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

56 vues18 pagesThe document provides background information on the Arab Spring, a wave of protests and demonstrations that began in December 2010 in Tunisia and spread to other countries in the Arab world. By December 2013, rulers had been forced from power in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen due to uprisings. Protests also occurred in other countries. The Arab Spring was fueled by public dissatisfaction with authoritarian regimes, corruption, economic issues, and demands for political change, especially among youth populations. Long-simmering tensions in several countries were exacerbated by events like the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia in 2010, which helped spark the initial uprising there.

Description originale:

This document explores details about the Arab spring.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThe document provides background information on the Arab Spring, a wave of protests and demonstrations that began in December 2010 in Tunisia and spread to other countries in the Arab world. By December 2013, rulers had been forced from power in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen due to uprisings. Protests also occurred in other countries. The Arab Spring was fueled by public dissatisfaction with authoritarian regimes, corruption, economic issues, and demands for political change, especially among youth populations. Long-simmering tensions in several countries were exacerbated by events like the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia in 2010, which helped spark the initial uprising there.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

56 vues18 pagesThe Arab Spring

Transféré par

JaveriarehanThe document provides background information on the Arab Spring, a wave of protests and demonstrations that began in December 2010 in Tunisia and spread to other countries in the Arab world. By December 2013, rulers had been forced from power in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen due to uprisings. Protests also occurred in other countries. The Arab Spring was fueled by public dissatisfaction with authoritarian regimes, corruption, economic issues, and demands for political change, especially among youth populations. Long-simmering tensions in several countries were exacerbated by events like the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia in 2010, which helped spark the initial uprising there.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 18

6/10/2014 10:03:00 AM

The Arab Spring (Arabic: , ar-rab al-arab) is a

revolutionary wave of demonstrations and protests (both non-violent and

violent), riots, and civil wars in the Arab world that began on 18 December

2010.

By December 2013, rulers had been forced from power in Tunisia,[3] Egypt

(twice),[4] Libya,[5] and Yemen;[6] civil uprisings had erupted in Bahrain[7]

and Syria;[8] major protests had broken out in Algeria,[9] Iraq,[10]

Jordan,[11] Kuwait,[12] Morocco,[13] and Sudan;[14] and minor protests

had occurred in Mauritania,[15] Oman,[16] Saudi Arabia,[17] Djibouti,[18]

Western Sahara,[19] and the Palestinian territories.

Weapons and Tuareg fighters returning from the Libyan Civil War stoked a

simmering conflict in Mali which has been described as "fallout" from the

Arab Spring in North Africa.[20] The sectarian clashes in Lebanon were

described as a spillover of violence from the Syrian uprising and hence the

regional Arab Spring.[21]

The protests have shared some techniques of civil resistance in sustained

campaigns involving strikes, demonstrations, marches, and rallies, as well as

the effective use of social media[22][23] to organize, communicate, and

raise awareness in the face of state attempts at repression and Internet

censorship.[24][25]

Many Arab Spring demonstrations have been met with violent responses

from authorities,[26][27][28] as well as from pro-government militias and

counter-demonstrators. These attacks have been answered with violence

from protestors in some cases.[29][30][31] A major slogan of the

demonstrators in the Arab world has been Ash-sha`b yurid isqat an-nizam

("the people want to bring down the regime")

The Arab Spring is widely believed to have been instigated by dissatisfaction

with the rule of local governments, though some have speculated that wide

gaps in income levels may have had a hand as well.[45] Numerous factors

have led to the protests, including issues such as dictatorship or absolute

monarchy, human rights violations, political corruption (demonstrated by

Wikileaks diplomatic cables),[46] economic decline, unemployment, extreme

poverty, and a number of demographic structural factors,[47] such as a

large percentage of educated but dissatisfied youth within the

population.[48] Also, some - like Slovenian philosopher Slavoj iek - name

the 20092010 Iranian election protests as an additional reason behind the

Arab Spring.[49] The Kyrgyz Revolution of 2010 might also have been a

factor influencing its beginning.[50] Catalysts for the revolts in all Northern

African and Persian Gulf countries have included the concentration of wealth

in the hands of autocrats in power for decades, insufficient transparency of

its redistribution, corruption, and especially the refusal of the youth to

accept the status quo.[51] Increasing food prices and global famine rates

have contested but peaceful elections, fast-growing but liberal economy,

secular constitution but Islamist government, created a model (the Turkish

model) if not a motivation for protestors in neighbouring states.[52]

Tunisia experienced a series of conflicts over the past three years, the most

notable occurring in the mining area of Gafsa in 2008, where protests

continued for many months. These protests included rallies, sit-ins, and

strikes, during which there were two fatalities, an unspecified number of

wounded, and dozens of arrests.[53][54] The Egyptian labor movement had

been strong for years, with more than 3,000 labor actions since 2004.[55]

One important demonstration was an attempted workers' strike on 6 April

2008 at the state-run textile factories of al-Mahalla al-Kubra, just outside

Cairo. The idea for this type of demonstration spread throughout the

country, promoted by computer-literate working class youths and their

supporters among middle-class college students.[55] A Facebook page, set

up to promote the strike, attracted tens of thousands of followers. The

government mobilized to break the strike through infiltration and riot police,

and while the regime was somewhat successful in forestalling a strike,

dissidents formed the "6 April Committee" of youths and labor activists,

which became one of the major forces calling for the anti-Mubarak

demonstration on 25 January in Tahrir Square.[55]

In Algeria, discontent had been building for years over a number of issues.

In February 2008, United States Ambassador Robert Ford wrote in a leaked

diplomatic cable that Algeria is 'unhappy' with long-standing political

alienation; that social discontent persisted throughout the country, with food

strikes occurring almost every week; that there were demonstrations every

day somewhere in the country; and that the Algerian government was

corrupt and fragile.[56] Some have claimed that during 2010 there were as

many as '9,700 riots and unrests' throughout the country.[57] Many protests

focused on issues such as education and health care, while others cited

rampant corruption.[58]

In Western Sahara, the Gdeim Izik protest camp was erected 12 kilometres

(7.5 mi) south-east of El Aain by a group of young Sahrawis on 9 October

2010. Their intention was to demonstrate against labor discrimination,

unemployment, looting of resources, and human rights abuses.[59] The

camp contained between 12,000 and 20,000 inhabitants, but on 8 November

2010 it was destroyed and its inhabitants evicted by Moroccan security

forces. The security forces faced strong opposition from some young Sahrawi

civilians, and rioting soon spread to El Aain and other towns within the

territory, resulting in an unknown number of injuries and deaths. Violence

against Sahrawis in the aftermath of the protests was cited as a reason for

renewed protests months later, after the start of the Arab Spring.[60]

The catalyst for the current escalation of protests was the self-immolation of

Tunisian Mohamed Bouazizi. Unable to find work and selling fruit at a

roadside stand, on 17 December 2010, a municipal inspector confiscated his

wares. An hour later he doused himself with gasoline and set himself afire.

His death on 4 January 2011[61] brought together various groups

dissatisfied with the existing system, including many unemployed, political

and human rights activists, labor, trade unionists, students, professors,

lawyers, and others to begin the Tunisian Revolution.[53]

The killing of Ambassador Stevens and three other Americans in Libya is

brutal proof that the turbulence that has shaken the Middle East since the

Arab Spring began has dangerous consequences for the United States.

Libya, of course, is a country that the United States helped liberate from

Qaddafis tyranny, and Americans understandably expected that gratitude,

not murder, would be the result. Counter-demonstrations in Tripoli suggest

that many Libyans remain thankful for U.S. support and oppose the violence,

but the scale of demonstrations in Libya as well as large protests in Egypt

and Yemen suggest that the region remains a dangerous place for Americans

and that many people in these countries have a hostile view of the United

States.

The collapse of authority in many countries has led to lawlessness.

Dictatorship, for all its brutality and many faults, meant that American

officials were not harmed by angry mobsunless the government wanted

the mobs to do so. Dictators fell, but strong regimes have not always taken

their place. Power vacuums replaced tyrannies in Iraq, Libya, and Yemen.

Should Assad go, Syria too will probably have a weak government at best.

As a result, even a small group of militants can wreak havoc.

THE CAUSES OF THE ARAB SPRING

William Quandt has astutely argued that authoritarian regimes base their

survival on four ingredients: ideology, repression, payoffs, and elite

solidarity. In Tunisia and Egypt the ideological justifications for rule had long

since failed to have any purchase on the population. The acceptance of

neoliberal rhetoric by the governing elite stripped them of their socialist and

developmental justification for authoritarian rule. In its place they

increasingly resorted to a conspiratorial nationalism, blaming economic

failure on a shadowy and shifting coalition of external actors. Given Hosni

Mubaraks close working relationship with the Israeli government and

Egypts financial dependence on American aid, the use of nationalist

paranoia as a justification for rule was bound to have a limited appeal. This

was especially the case amongst an increasingly youthful population who

had no memory of the post-colonial glory of Nasser in Egypt or Bourgiba in

Tunisia.

The increasingly brazen nature of regime corruption in both Egypt and

Tunisia was enabled through the exclusion of the majority of the population

from the economy. Family members of the ruling elite flaunted their wealth

in the streets of Tunis and Cairo as standards of living for the majority of the

population stagnated. The constituency for revolutionary change steadily

expanded as the percentage of the population between 15 and 29 years-old

rose, by 50 percent in

Tunisia and 60 percent in Egypt since 1990. Finally, as the membership of

the coalition of the dispossessed increased, the ability of the Egyptian and

Tunisian regimes to provide pay-offs was also put under increasing pressure.

In order to buy off its population the Egyptian government was reportedly

spending $3 billion a year subsidising the price of bread (Egypt is the worlds

largest importer of wheat with Tunisia coming in at number seventeen).

Through 2007 and 2008 the world price of wheat steadily rose, causing a

thirty-seven percent increase in the price of bread in Egypt.

Although the death of Mohamed Bouazizi acted as a catalyst for the

sustained protest against the formerly robust dictatorships in Tunisia, Egypt

and then Libya and Syria, the structural drivers had long been in place.

Finally, in the face of extended street protests Quandts fourth pillar of

regime stability, elite solidarity cracked. In Tunisia, Ben Ali ordered Rachid

Ammar, the head of the army to fire on protestors. With a strategic eye on

the presidents increasing unpopularity and his own place in any future post-

regime change Tunisia Anwar refused, and sealed the fate of Ben Alis rule. A

similar dynamic was soon at work in Egypt, where Field Marshall Mohamed

Hussein Tantawi refused to order the army to fire on demonstrators, thus

guaranteeing his survival after the regime change that inevitably followed

his refusal to sanction violence.

Unlike the arrival in the Middle East of the World Bank and the IMF in the

1980s or the demonstration effect of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the

liberation of Kuwait in 1989 and 1991, the Arab Spring of 2011 was a wholly

indigenous movement driven forward by the brave agency of young people

in Cairo and Tunisia. The contrast between the hesitant, contradictory and

reactive approach of the Obama administration and the dynamic behaviour

of the Arab Street only served to highlight that it was Arabs once again

making their own history, in spite and not because of the international

dynamics that had long been predicted to bring change to the region.

11

Caus

es

Authoritarianism

Demographic structural factors

Political corruption

Human rights violations

Inflation

Kleptocracy

Sectarianism

Unemployment

Self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi

Higher Food Prices due to the Russian

export ban on its remaining 2010

harvest which was damaged by wild

fires[1][2]

Goals Democracy

Free elections

Human rights

Employment

Regime change

Islamism

Secularism

Meth

ods

Civil disobedience

Civil resistance

Defection

Demonstrations

Insurgency

Internet activism

Protest camps

Revolution

Riots

Self-immolation

Sit-ins

Strike actions

Urban warfare

Uprising

s of September 2012, governments have been overthrown in four countries.

Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia on 14 January

2011 following the Tunisian Revolution protests. In Egypt, President Hosni

Mubarak resigned on 11 February 2011 after 18 days of massive protests,

ending his 30-year presidency. The Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was

overthrown on 23 August 2011, after the National Transitional Council (NTC)

took control of Bab al-Azizia. He was killed on 20 October 2011, in his

hometown of Sirte after the NTC took control of the city. Yemeni President

Ali Abdullah Saleh signed the GCC power-transfer deal in which a

presidential election was held, resulting in his successor Abd al-Rab Mansur

al-Hadi formally replacing him as the president of Yemen on 27 February

2012, in exchange for immunity from prosecution.

Inspired by the uprising in Tunisia and prior to his entry as a central figure in

Egyptian politics, potential presidential candidate Mohamed ElBaradei

warned of a "Tunisia-style explosion" in Egypt.[195]

Protests in Egypt began on 25 January 2011 and ran for 18 days. Beginning

around midnight on 28 January, the Egyptian government attempted,

somewhat successfully, to eliminate the nation's Internet access,[25] in

order to inhibit the protesters' ability use media activism to organize through

social media.[196] Later that day, as tens of thousands protested on the

streets of Egypt's major cities, President Hosni Mubarak dismissed his

government, later appointing a new cabinet. Mubarak also appointed the

first Vice President in almost 30 years.

The U.S. embassy and international students began a voluntary evacuation

near the end of January, as violence and rumors of violence

escalated.[197][198]

On 10 February, Mubarak ceded all presidential power to Vice President

Omar Suleiman, but soon thereafter announced that he would remain as

President until the end of his term.[199] However, protests continued the

next day, and Suleiman quickly announced that Mubarak had resigned from

the presidency and transferred power to the Armed Forces of Egypt.[200]

The military immediately dissolved the Egyptian Parliament, suspended the

Constitution of Egypt, and promised to lift the nation's thirty-year

"emergency laws". A civilian, Essam Sharaf, was appointed as Prime Minister

of Egypt on 4 March to widespread approval among Egyptians in Tahrir

Square.[201] Violent protests however, continued through the end of 2011

as many Egyptians expressed concern about the Supreme Council of the

Armed Forces' perceived sluggishness in instituting reforms and their grip on

power.[202]

Hosni Mubarak and his former interior minister Habib al-Adli were convicted

to life in prison on the basis of their failure to stop the killings during the first

six days of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution.[203] His successor, Mohamed

Morsi, was sworn in as Egypt's first democratically elected president before

judges at the Supreme Constitutional Court.[204] Fresh protests erupted in

Egypt on 22 November 2012. On 3 July 2013, the military overthrew the

replacement government and President Morsi was removed from

power.[205]

Emergency law[edit]

Main article: Emergency law in Egypt

An emergency law (Law No. 162 of 1958) was enacted after the 1967 Six-

Day War. It was suspended for 18 months in the early 1980s[55] and has

otherwise continuously been in effect since President Sadat's 1981

assassination.[56] Under the law, police powers are extended, constitutional

rights suspended, censorship is legalised,[57] and the government may

imprison individuals indefinitely and without reason. The law sharply limits

any non-governmental political activity, including street demonstrations,

non-approved political organizations, and unregistered financial

donations.[55] The Mubarak government has cited the threat of terrorism in

order to extend the emergency law,[56] claiming that opposition groups like

the Muslim Brotherhood could come into power in Egypt if the current

government did not forgo parliamentary elections and suppress the group

through actions allowed under emergency law.[58] This has led to the

imprisonment of activists without trials,[59] illegal undocumented hidden

detention facilities,[60] and rejecting university, mosque, and newspaper

staff members based on their political inclination.

Police brutality[edit]

Further information: Law enforcement in Egypt

According to a report from the U.S. Embassy in Egypt, police brutality has

been common and widespread in Egypt.[64] In the five years prior to the

revolution, the Mubarak regime denied the existence of torture or abuse

carried out by the police. However, many claims by domestic and

international groups provided evidence through cellphone videos or first-

hand accounts of hundreds of cases of police abuse.[65

Corruption in government elections[edit]

Corruption, coercion to not vote, and manipulation of election results

occurred during many of the elections over 30 years.[77] Until 2005,

Mubarak was the only candidate to run for the presidency, on a yes/no

vote.[78] Mubarak won five consecutive presidential elections with a

sweeping majority. Opposition groups and international election monitoring

agencies accused the elections of being rigged. These agencies have not

been allowed to monitor the elections. The only opposing presidential

candidate in recent Egyptian history, Ayman Nour, was imprisoned before

the 2005 elections.[79] According to a 2007 UN survey, voter turnout was

extremely low (around 25%) because of the lack of trust in the corrupt

representational system.[

Demographic and economic challenges[edit]

Unemployment and reliance on subsidized goods[edit]

Further information: Demographics of Egypt, Demographic trap and Youth

bulge

Population pyramid in 2005. Many of those 30 and younger are educated

citizens who are experiencing difficulty finding work.

The population of Egypt grew from 30,083,419 in 1966[80] to roughly

79,000,000 by 2008.[81] The vast majority of Egyptians live in the limited

spaces near the banks of the Nile River, in an area of about 40,000 square

kilometers (15,000 sq mi), where the only arable land is found. In late 2010

around 40% of Egypt's population of just under 80 million lived on the fiscal

income equivalent of roughly US$2 per day, with a large part of the

population relying on subsidized goods.[1]

According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics and other

proponents of demographic structural approach (cliodynamics), a basic

problem in Egypt is unemployment driven by a demographic youth bulge:

with the number of new people entering the job force at about 4% a year,

unemployment in Egypt is almost 10 times as high for college graduates as

it is for people who have gone through elementary school, particularly

educated urban youththe same people who were out in the streets during

the revolution.[82][83]

A poor neighbourhood in Cairo.

Poor living conditions and economic conditions[edit]

Further information: Economy of Egypt

Egypt's economy was highly centralised during the tenure of President

Gamal Abdel Nasser but opened up considerably under President Anwar

Sadat and Mubarak. From 2004 to 2008 the Mubarak-led government

aggressively pursued economic reforms to attract foreign investment and

facilitate GDP growth, but postponed further economic reforms because of

global economic turmoil. The international economic downturn slowed

Egypt's GDP growth to 4.5% in 2009. In 2010 analysts said the government

of Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif would need to restart economic reforms to

attract foreign investment, boost growth, and improve economic conditions.

Despite high levels of national economic growth over the past few years,

living conditions for the average Egyptian remained relatively poor,[84]

though better than many other countries in Africa[82] where no significant

social explosions were observed, which indicates that poverty cannot be

regarded as a real cause of the Egyptian revolution.

Corruption among government officials[edit]

Further information: Crime in Egypt

Political corruption in the Mubarak administration's Ministry of Interior rose

dramatically due to the increased level of control over the institutional

system necessary to prolong the presidency.[85] The rise to power of

powerful businessmen in the NDP, in the government, and in the People's

Assembly led to massive waves of anger during the years of Prime Minister

Ahmed Nazif's government. An example is Ahmed Ezz's monopolising the

steel industry in Egypt by holding more than 60% of the market share.[86]

Aladdin Elaasar, an Egyptian biographer and an American professor,

estimated that the Mubarak family was worth from $50 to

$70 billion.[87][88]

The wealth of Ahmed Ezz, the former NDP Organisation Secretary, was

estimated to be 18 billion Egyptian pounds;[89] the wealth of former

Housing Minister Ahmed al-Maghraby was estimated to be more than

11 billion Egyptian pounds;[89] the wealth of former Minister of Tourism

Zuhair Garrana is estimated to be 13 billion Egyptian pounds;[89] the wealth

of former Minister of Trade and Industry, Rashid Mohamed Rashid, is

estimated to be 12 billion Egyptian pounds;[89] and the wealth of former

Interior Minister Habib al-Adly was estimated to be 8 billion Egyptian

pounds.[89]

The perception among Egyptians was that the only people to benefit from

the nation's wealth were businessmen with ties to the National Democratic

Party; "wealth fuels political power and political power buys wealth."[90]

During the Egyptian parliamentary election, 2010, opposition groups

complained of harassment and fraud perpetrated by the government.

Opposition and civil society activists called for changes to a number of legal

and constitutional provisions which affect elections.

[

citation needed

]

In 2010, Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI)

report assessed Egypt with a CPI score of 3.1, based on perceptions of the

degree of corruption from business people and country analysts (with 10

being clean and 0 being totally corrupt).[91]

Lead-up to the protests[edit]

To prepare for a possible overthrow of Mubarak, opposition groups studied

the work of Gene Sharp on non-violent revolution and worked with leaders

of Otpor!, the student-led Serbian uprising of 2000. Copies of Sharp's list of

198 non-violent "weapons", translated into Arabic and not always attributed

to him, were circulated in Tahrir Square during its occupation.[92][93]

Tunisian revolution[edit]

Main article: Tunisian revolution

Further information: Arab Spring

After the ousting of Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali due to mass

protests, many analysts, including former European Commission President

Romano Prodi, saw Egypt as the next country where such a revolution might

occur.[94] The Washington Post commented, "The Jasmine Revolution [...]

should serve as a stark warning to Arab leaders beginning with Egypt's 83-

year-old Hosni Mubarak that their refusal to allow more economic and

political opportunity is dangerous and untenable."[95] Others held the

opinion that Egypt was not ready for revolution, citing little aspiration of the

Egyptian people, low educational levels, and a strong government with the

support of the military.[96] The BBC said, "The simple fact is that most

Egyptians do not see any way that they can change their country or their

lives through political action, be it voting, activism, or going out on the

streets to demonstrate."[97]

Self-immolation[edit]

A protester holds an Egyptian flag during the protests that started on 25

January 2011 in Egypt

Following the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia on 17

December, a man set himself ablaze on 17 December in front of the Tunisian

parliament;[98] and about five more attempts of self-immolation

followed.[96]

National Police Day protests[edit]

Opposition groups planned a day of revolt for 25 January, coinciding with the

National Police Day. The purpose was to protest against abuses by the police

in front of the Ministry of Interior.[99] These demands expanded to include

the resignation of the Minister of Interior, an end to State corruption, the

end of Egyptian emergency law, and term limits for the president.

Many political movements, opposition parties, and public figures supported

the day of revolt, including Youth for Justice and Freedom, Coalition of the

Youth of the Revolution, the Popular Democratic Movement for Change, the

Revolutionary Socialists and the National Association for Change. The April 6

Youth Movement was a major supporter of the protest and distributed

20,000 leaflets saying "I will protest on 25 January to get my rights". The

Ghad El-Thawra Party, Karama, Wafd and Democratic Front supported the

protests. The Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt's largest opposition group,[100]

confirmed on 23 January that it would participate.[100][101] Public figures

including novelist Alaa Al Aswany, writer Belal Fadl, and actors Amr Waked

and Khaled Aboul Naga announced they would participate. However, the

leftist National Progressive Unionist Party (the Tagammu) stated it would not

participate. The Coptic Church urged Christians not to participate in the

protests.[100]

Twenty-six-year-old Asmaa Mahfouz was instrumental[102] in sparking the

protests.[103][104] In a video blog posted a week before National Police

Day,[105] she urged the Egyptian people to join her on 25 January in Tahrir

Square to bring down Mubarak's regime.[106] Mahfouz's use of video

blogging and social media went viral[107] and urged people not to be

afraid.[108] The Facebook group set up for the event attracted 80,000

attendees.

In the 1960s an American political scientist, Malcolm Kerr, coined the phrase

the Arab Cold War to describe the regional rivalry between two blocks of

Arab states each backed by superpower patrons. Mr Kerr accepted that this

rivalry ended in the 1970s but in the first decade of the 21st century several

commentators claimed that, following increased US intervention after 9/11,

once again the Middle East was being divided into two blocks and a new

Middle Eastern Cold War was taking shape. This bipolarity saw one camp led

by the US and its principle allies Saudi Arabia, Israel and Egypt face

down a second, self-styled resistance camp composed of Iran, Syria,

Lebanons Hezbollah and the Palestinian militia/party, Hamas. As in the

1950s and 60s, these two blocks found themselves competing in numerous

minor conflicts, political battles and the media, in a bid to dominate the

region, with Lebanon, Iraq and Palestine forming the key battlegrounds.

The Arab Spring has changed this. While Israel and Saudi Arabia persist with

their old narrative about the threat from Iran, in reality the popular uprisings

of 2011 has changed the environment around all three states. New actors

that had previously stood back from the region, such as Turkey and Qatar,

stand to increase their influence and clout as a consequence of the unrest

while formerly influential states such as Egypt and Syria look set for

prolonged instability and weakness. Alongside this the global context has

changed. The emerging BRICS powers have enhanced their influence and

importance, at the very moment that the US and EU appear weaker

following internal economic turmoil. The result is that instead of two clear

blocks competing, the Middle East after the Arab Spring looks set to be

multi-polar, with many different regional and global powers vying for

influence in the different political and, possibly, military conflicts that the

uprisings have created.

The idea that social forces such as ideas, norms and rules influence states

identities and interests has gained increased acknowledgement in the study

of the current international system, as mainstream international relations

theories seem to offer only limited applications to contemporary events. As

Nicholas Onuf argues, international politics is a world of our making; there

is a process of interaction between agency and structure and the

international system is constituted by ideas, not material forces (Onuf,

1989:341). Using the Arab Spring as a case study throughout this essay, it

will be argued that social constructivism can explain events in the

international system due to its ontological position that emphasizes that

structures not only constrain; they also constitute the identity of actors

Many of the mainstream international relations theories assume that all

states concerned have a level of similarity resulting in fixed generalization

and theory construction (Fierke in Dunne, 2010:179). However, despite the

generalization, these theories failed to predict and explain international

politics in times such as the outbreak of the Cold War, post-Cold War events,

and recently the Arab Spring. Social constructivism, on the other hand,

differs from these generalizations as it emphasizes the importance of social

dimensions and gives more meaning to norms, language, rules and identities

(Barnett, 2011:151-153). These make the international system a constant

process of construction and interaction, where structures are shaped by

agency and vice versa and are not fixed through generalizations. As

Alexander Wendt wrote: Anarchy is what states make of it; unlike the

rationalists, who emphasize that structures constrain, norms and identity

have constitutive roles in relation to the relationship between agency and

structure (Wendt, 1992). Therefore, constructivists see knowledge as

constructed as opposed to created. Epistemologically, social constructivism

is in-between positivist and post-positivist perspectives, making it adaptive,

organized and constrained at the same time.

One of the interpretations of the origins of the Arab Spring is that it erupted

in Tunisia, a small country that was more educated than the Arab norm and

with strong links to Europe (BBC, 2013). Social constructivism can explain

this as the proliferation of democratic norms, largely brought about through

media technologies and social networks interactions, often labeled as the

concept of globalization, which led the youth in the Middle East to become

the main agent and force of change during the Arab Spring. It can be argued

that the Arab Spring would not have happened without social interaction, as

these exchanges both on the domestic and international level mutually

constituted conflict. Contrary to Samuel P. Huntingtons The Clash of

Civilizations theory (Huntington, 1993), Arabs did not despise Western

liberty but they instead desired it (Mogahed, 2012). Ideas of human rights,

freedom, social equity and dignity flooded the Middle East and weakened the

structure that had been established in the area for centuries. Even though

structure clearly sets parameters in a political system, these parameters are

not bound to be irreversible. Indeed, it might be because many leaders in

the Middle East assumed that their set parameters were irreversible, that

they believed in the durability of their political authoritarianism (El-Mahdi,

2012:13). Because they felt reassured in their supposedly safe identity and

structure, the increased influx of ideas and Western norms through a

process of globalization was not deemed as a threat. But the agents of

political socialization were adept at influencing the peoples consciousness,

especially through media (El-Mahdi, 2012:63). The more frequent the social

interactions became, through the help of social platforms such as Facebook,

Twitter and BlackBerry Messenger, the more the people were ready to

reconstruct their social identities. As Toby Dodge wrote: The demands for

full citizenship, for the recognition of individual political rights, were a

powerful unifying theme across the Arab revolutions (Dodge, 2012). This

human consciousness was one of the most powerful tools for the structural

change, where the relationship between material forces and ideas

consequently led to the people questioning the origins of what they had

accepted as a fact of their lives, resulting in the idea to establish an

alternative pathway, an alternative world in the Middle East

6/10/2014 10:03:00 AM

6/10/2014 10:03:00 AM

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Arab Revolts: Dispatches on Militant Democracy in the Middle EastD'EverandThe Arab Revolts: Dispatches on Militant Democracy in the Middle EastPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument5 pagesArab Springpaolomas36Pas encore d'évaluation

- Devs in Middle East The Arab Spring and Its FalloutDocument15 pagesDevs in Middle East The Arab Spring and Its FalloutPakistanPas encore d'évaluation

- Primavara ArabaDocument57 pagesPrimavara ArabaLoredana GavrilPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Uprising A Glimmer of HopeDocument7 pagesArab Uprising A Glimmer of HopeSadiq JalalhshsPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Uprising, A Glimmer of Hope For A New Beginning in Middle EastDocument6 pagesArab Uprising, A Glimmer of Hope For A New Beginning in Middle EastIkra MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Giobalization in A Changing World: The Big QuestionsDocument39 pagesGiobalization in A Changing World: The Big QuestionsMarco Antonio Tumiri L�pezPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument5 pagesArab SpringAmoùr De Ma ViePas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument5 pagesArab SpringAnupama RawatPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Spring.. How Did It SpreadDocument3 pagesArab Spring.. How Did It SpreadjhanaviPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument23 pagesArab Springsafaasim62Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Spring Uprising MiddleEastDocument9 pagesThe Spring Uprising MiddleEast654fh7qcxzPas encore d'évaluation

- Autocratic Style AssignmentDocument5 pagesAutocratic Style AssignmentLeeroy ButauPas encore d'évaluation

- The Middle East C RisisDocument17 pagesThe Middle East C RisisHarshit UpadhyayPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Spring Research PaperDocument5 pagesArab Spring Research Paperfvf2j8q0100% (1)

- The Arab SpringDocument11 pagesThe Arab SpringArafat DreamtheterPas encore d'évaluation

- The Arab Spring Was A Series of ProDocument5 pagesThe Arab Spring Was A Series of Prosst nkbps100% (1)

- The Arab SpringDocument5 pagesThe Arab SpringBest PricePas encore d'évaluation

- CTC - Topic ADocument3 pagesCTC - Topic ARuhaan AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Arab SpringDocument4 pagesThesis Arab Springlisamoorewashington100% (1)

- Thesis Statement For Arab SpringDocument8 pagesThesis Statement For Arab Springchristinajohnsonanchorage100% (2)

- Arab Spring-1Document30 pagesArab Spring-1Ishika JainPas encore d'évaluation

- The Egyptian RevolutionDocument26 pagesThe Egyptian Revolutionahmed hassanPas encore d'évaluation

- Revolutio in EgyptDocument12 pagesRevolutio in Egyptsukhjeet98Pas encore d'évaluation

- Democratic and Political Dynamics of Middle East: An Analysis of Internal and External InfluenceDocument8 pagesDemocratic and Political Dynamics of Middle East: An Analysis of Internal and External Influencesadafshahbaz7777Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assess The Political Cultural and EconomDocument17 pagesAssess The Political Cultural and EconomNAYEON KANGPas encore d'évaluation

- Pol Science Final DraftDocument15 pagesPol Science Final DraftAkshayvat KislayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Arab Uprising: Causes, Prospects and ImplicationsDocument10 pagesThe Arab Uprising: Causes, Prospects and Implicationssak_akPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Spring Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesArab Spring Thesis StatementAddison Coleman100% (1)

- GCSP Policy Paper N°11: The Arab Revolt: Roots and PerspectivesDocument6 pagesGCSP Policy Paper N°11: The Arab Revolt: Roots and PerspectivesAnonymous uAIHiQZQMPas encore d'évaluation

- 18 December 2010 in With The: Tunisia Tunisian RevolutionDocument1 page18 December 2010 in With The: Tunisia Tunisian RevolutionMansaf AbroPas encore d'évaluation

- Corruption of Arab Leaders: Causes of "Arab Spring" - Current Affairs CSS 2015 Solved PaperDocument5 pagesCorruption of Arab Leaders: Causes of "Arab Spring" - Current Affairs CSS 2015 Solved Paperengrsana ullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Background Narrative Arabian SpringDocument14 pagesBackground Narrative Arabian Springyaqoob008Pas encore d'évaluation

- Background Guide: League of Arab StatesDocument11 pagesBackground Guide: League of Arab StatesAbhilash ChandranPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument5 pagesArab SpringPaul DookPas encore d'évaluation

- Excerpt of "Identity: The Demand For Dignity and The Politics of Resentment"Document5 pagesExcerpt of "Identity: The Demand For Dignity and The Politics of Resentment"wamu885100% (1)

- Arabic SpringDocument4 pagesArabic SpringLibre AccesoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dissertation CourseworkDocument4 pagesDissertation CourseworkThomasPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument1 pageArab SpringStefan NedeljkovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Tanggol, Khalil Tamkeen A. Is 12 Xa Egypt and Tunis During The Arab SpringDocument3 pagesTanggol, Khalil Tamkeen A. Is 12 Xa Egypt and Tunis During The Arab SpringKHALIL TAMKEEN ALI TANGGOLPas encore d'évaluation

- Libya Revolution DocumentDocument11 pagesLibya Revolution Documentapi-299863619Pas encore d'évaluation

- Freedom Index 2012 Booklet - FinalDocument40 pagesFreedom Index 2012 Booklet - FinalAdriana PopescuPas encore d'évaluation

- $RFMA1AQDocument5 pages$RFMA1AQducnguyenminh01102002Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Lure of Authoritarianism: The Maghreb after the Arab SpringD'EverandThe Lure of Authoritarianism: The Maghreb after the Arab SpringPas encore d'évaluation

- The Arab SpringDocument5 pagesThe Arab SpringAzzedine AzzimaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument40 pagesArab SpringEsih WinangsihPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Spring Research PapersDocument7 pagesArab Spring Research Paperskbcymacnd100% (1)

- From The Arab AwakeningDocument7 pagesFrom The Arab AwakeningSalim UllahPas encore d'évaluation

- Possible Causes:: Image: Goran Tomasevic / ReutersDocument4 pagesPossible Causes:: Image: Goran Tomasevic / ReutersManini JaiswalPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument1 pageArab SpringPtb4docPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab SpringDocument10 pagesArab Springaliya fatimaPas encore d'évaluation

- He 2011 Libyan UprisingDocument23 pagesHe 2011 Libyan UprisingSachin SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Without Pplag FinalDocument16 pagesArab Without Pplag FinalDoyel MehtaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Spring AssignmentDocument9 pagesArab Spring AssignmentMuhibban e Aehle e Bait علیہ السلام The Best onesPas encore d'évaluation

- Theimpactofconflictandpoliticalinstabilityon AfricaDocument12 pagesTheimpactofconflictandpoliticalinstabilityon AfricaSusan SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Purification of The HeartDocument8 pagesPurification of The HeartJaveriarehanPas encore d'évaluation

- Annelies Marie (Anne) Frank (: Achterhuis English: The Secret Annex), in Which She Documents Her Life inDocument2 pagesAnnelies Marie (Anne) Frank (: Achterhuis English: The Secret Annex), in Which She Documents Her Life inJaveriarehanPas encore d'évaluation

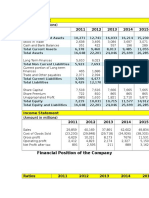

- Financial Position of The Engro FoodsDocument2 pagesFinancial Position of The Engro FoodsJaveriarehanPas encore d'évaluation

- Organization Government BusinessDocument2 pagesOrganization Government BusinessJaveriarehanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bachelor of Science Information Technology MinDocument2 pagesBachelor of Science Information Technology MinYoyo ManuPas encore d'évaluation

- 2015-16 Principal Internship Weekly Reflection Log For Daniel SanchezDocument17 pages2015-16 Principal Internship Weekly Reflection Log For Daniel Sanchezapi-317986262Pas encore d'évaluation

- Villanueva v. Oro - Insurance ProceedsDocument4 pagesVillanueva v. Oro - Insurance ProceedsLord AumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study Humanized RobotsDocument3 pagesCase Study Humanized RobotsAakash YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Undergraduate Curriculum Vitae: PublicationsDocument1 pageUndergraduate Curriculum Vitae: PublicationsMuhammad Zaim EmbongPas encore d'évaluation

- Bosch CM Coach enDocument21 pagesBosch CM Coach enHélder AraujoPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Publishers - Scholarly Open AccessDocument22 pagesList of Publishers - Scholarly Open AccessHerman SjahruddinPas encore d'évaluation

- 2550m FormDocument1 page2550m FormAileen Jarabe80% (5)

- HP Board of School Education Dharamshala Syllabus: Subject: Computer Science Class: 9Document4 pagesHP Board of School Education Dharamshala Syllabus: Subject: Computer Science Class: 9Principal AveriPas encore d'évaluation

- Tasawwuf: SlamicDocument221 pagesTasawwuf: SlamicMas ThulanPas encore d'évaluation

- Director Manager Operations Pharmacy in Los Angeles CA Resume Philip HoDocument2 pagesDirector Manager Operations Pharmacy in Los Angeles CA Resume Philip HoPhilipHo2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 024 - Abuse of Authority by A Majority of Shareholders in A Company (380-409) .UnlockedDocument30 pages024 - Abuse of Authority by A Majority of Shareholders in A Company (380-409) .UnlockedAlishaPas encore d'évaluation

- GA5FF - tcm266 646875Document1 pageGA5FF - tcm266 646875peterpunk75Pas encore d'évaluation

- MIP291Document1 pageMIP291RogerioPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter One: Introduction To Business TaxesDocument9 pagesChapter One: Introduction To Business TaxesKai KimPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual Config OLT C320Document12 pagesManual Config OLT C320Achmad SholehanPas encore d'évaluation

- Walmart CaseDocument1 pageWalmart Casemaria clara drzeviechi silvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Law RTP May 2023Document57 pagesLaw RTP May 2023ROCKYPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Presidents of The People's Republic of China - WikipediaDocument10 pagesList of Presidents of The People's Republic of China - WikipediaAli Nawaz tanwariPas encore d'évaluation

- E Directory Project ReportDocument11 pagesE Directory Project ReportVidhimanya Chamber of Commerce and IndustryPas encore d'évaluation

- Katrine PHD ThesisDocument207 pagesKatrine PHD ThesiszewhitePas encore d'évaluation

- Cartridge Valves Technical Information Directional Valves DCV 03Document12 pagesCartridge Valves Technical Information Directional Valves DCV 03francis_15inPas encore d'évaluation

- Family Managed Business Vs Non Family BusinessDocument4 pagesFamily Managed Business Vs Non Family BusinessKARISHMA RAJ0% (1)

- SinusitisDocument30 pagesSinusitisAbdiqani MahdiPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes Unit 1Document23 pagesNotes Unit 1div300482Pas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Degree PlanDocument8 pagesEngineering Degree Planashvinbalaraman0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Containerised Generator Sets DNVDocument17 pagesContainerised Generator Sets DNVEmmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Simulation of Manufacturing Process of NitrobenzeneDocument83 pagesSimulation of Manufacturing Process of NitrobenzeneRashid Fikri100% (1)

- Nirosoft Mobile Water Purification BrochureDocument4 pagesNirosoft Mobile Water Purification BrochureIsrael ExporterPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fractal Nature of The Programming Discourse CommunityDocument8 pagesThe Fractal Nature of The Programming Discourse Communityjoey9zPas encore d'évaluation