Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Cleaver V Mutual Reserve

Transféré par

Aisha MillerTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Cleaver V Mutual Reserve

Transféré par

Aisha MillerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

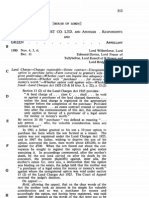

1Q. B. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION.

147

disputes to arbitration. This, however, is not a higher interpre- 1891

tation than was necessarily put on the language of the old Act, BAKEB

under which it was the universal practice to refer these cases, v * '

m

,

and does not mean that in all cases the written agreement to

FlRE AND

. . . LlL''E ASSUIt-

refer must be signed by both parties. I t is quite unnecessary AXCE CO.

to say more as to the decision in Caerleon Tinplate Co. v. A. L. smith, j .

Hughes (1) than that it turned entirely upon the peculiar facts

of the case; for I am convinced that the learned judges who

gave that decision would decide the present case in the same

way that we are deciding it. My brother Charles at chambers

was quite right, and his decision must be upheld.

Appeal dismissed.

Solicitors for plaintiff: Smiles & Co., for Beleher, Cardiff.

Solicitors for defendants : Bell, BrodricJc, <& Gray, for Gray &

Dodsworth, York.

W. J. B.

[IN THE COUET OP APPEAL.] 0. A.

CLEAVER AND OTHERS V. MUTUAL RESERVE FUND LIFE

1S91

ASSOCIATION. X6o

2

8.

3:

Insurance {Life)Insurance in favour of WifeDeath of Insured through

Crime of WifePublic PolicyResulting Trust in favour of Insured's

EstateAction hy Executors Married Women's Property Act, 1882

(45 & 46 Vict. c. 75), s. 11.

The executors of a person who has effected an insurance on his life for the

benefit of his wife can maintain an action on the policy notwithstanding the

fact that the death of the insured was caused by the felonious act of the wife.

The trust created by the policy in favour of the wife under the Married

Women's Property Act, 1882, s. 11, having become incapable of being per-

formed by reason of her crime, the insurance money forms part of the estate of

the insured; and as between his legal representatives and the insurers no

question of public policy arises to afford a defence to the action.

APPEAL from the judgment of the Queen's Bench Division

upon a question of law raised by the pleadings and ordered to

be decided by the Court pursuant to Order xxxiv. , r. 2, before

trial of the issues of fact.

(1) 60 L. J. (Q.B.) 640.

148 QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. [1892]

C A. The facts as al l eged by t he pl eadi ngs were as fol l ows:

1891 The st at ement of claim st at ed t hat J ames Maybri ck effected

CLEAVER an i nsurance on his life wi t h t he defendant s for 2000Z., i n favour

MUTUAL ^

u

^

s w

^

e

> Fl or ence El i zabet h Maybri ck. The policy st at ed t hat ,

EESEHVE f

or

tf

ie

consi derat i ons t her ei n ment i oned, t he Mut ual Eeser ve

FUND LIEE

ASSOCIATION. Fund Life Association received James Maybrick as a member of

the said association, and t hat there should be payable to Florence

E. Maybrick, his wife, if living at the time of the death of the

said member, otherwise to the legal representatives of such

member, the sum of 2000Z., within ninety days after receipt of

satisfactory evidence to the association of the death of the said

member. James Maybrick died on May 11, 1889. By his will he

appointed Thomas Maybrick and Michael Maybrick his exe-

cutors. On August 1, 1889, Florence E. Maybrick assigned by

deed to the plaintiff Cleaver the said policy and all her interest

thereunder, and notice of such assignment was duly given to the

defendants before the action. On August 30, 1889, Cleaver was

duly appointed administrator of the property and effects of

Florence E. Maybrick under 33 & 34 Vict. c. 23, s. 9 (the Act

to Abolish Forfeitures for Treason and Felony). The plaintiffs,

as such assignee or administrator and executors respectively

claimed payment of the insurance money.

By the statement of defence it was alleged that James

Maybrick died from poison, intentionally administered to him

by Florence E. Maybrick, and that she was, at the assizes

held at Liverpool on Jul y 25, 1889, tried and convicted upon

an indictment charging her with the wilful murder of James

Maybrick. The sentence of death passed upon Florence

E. Maybrick was afterwards commuted to penal servitude for

life.

The question of law to be decided was whether, if it were

proved that James Maybrick died from poison intentionally

administered to him by Florence E. Maybrick, that would afford

a defence to the action; (a) as against the plaintiff Cleaver as

assignee of the policy from Florence E. Maybrick; (J) as

against the plaintiff Cleaver as administrator under 33 & 34 Vict.

c. 23, s. 9; (c) as against the plaintiffs, Thomas Maybrick and

Michael Maybrick, as executors of James Maybrick.

1 Q. B. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. 149

The Divisional Court (Denman and Wills, J J.) gave judg- C.A.

ment for the defendants. 1891

CLEAVEB

Nov. 2 and 3. Sir Charles Russell, Q.C., and Reginald J. Smith, v.

for the plaintiffs. The executors of James Maybrick are entitled RESEUVE

to recover on the policy. This policy was a perfectly valid policy ASSOCIATION.

in its inception. So the case has no analogy to a case like Prince

of Wales Association v. Palmer (1), which was decided on the ground

that the insurance was a fraud ab initio. I t is clear that the

event happened upon which by the terms of the policy it was .to

become payable. The argument for the defendants is that public

policy may be invoked to relieve the defendants from performing

their contract. But it is contended that no question of public

policy arises as between the executors and the defendants; if any

such question comes in at all, it is at a later stage. The contract

of the defendants was with the insured, James Maybrick. The

right to recover on the policy vests in his executors, and it is

only when it is a question as to the application of the money by

them that considerations of public policy arise. I t is argued by

the defendants that the policy makes the money payable to the

wife only. That is not so. I t must be read by the light of the

Married Women' s Property Act, 1882. The contract was with

James Maybrick, and, there being no trustee appointed under

the 11th section, the policy, and all rights under it, vested in

his legal personal representatives. They hold in trust for the

wife so far only as any trust for her is legally recognisable; but

if the trust for her benefit cannot legally be performed by

reason of a rule of public policy, the money will form part of the

insured's personal estate. Whether that be so or not, however,

does not concern the defendants. They have nothing to do with

the application of the money. There can be no rule of public

policy that prevents the executors from recovering the money

which the defendants contracted with the insured to pay upon

his death, and in respect of which they have received the con-

sideration. The rule of public policy acted upon in Amicable

Assurance Society v. Bolland (2), applies only to cases where the

insured, with whom the contract is made, by his own crime

(1) 25 Beav. 605. (2) 4 Bli. (N.S.) 194 (Fauntleroy's Case).

150 QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. [1892]

C. A. causes his death. The rule in such a case is that it is against

189] public policy that the assignees of the contracting party should

CLEAVEU receive benefit from the contract through his crime. That has

MUTUAL

n o

application where the death is caused by the crime of a person

EESKHVK

w

ho is not a party to the contract: Waineivriqlit v. Bland. (1)

ASSOCIATION. [They also cited Horn v. Anglo-Australian Insurance Co. (2);

Moore v. Woolsey. (3) ]

Sir E. Clarice, 8.G., and Hextall, for the defendants. This

insurance was obviously effected under s. 11 of the Married

Women's Property Act, 1882, and it gives the whole benefit of

the insurance-money to the wife, if she survives the insured. I t

has been held in such a case that the insurance money goes to

the wife, not the husband's trustee in bankruptcy : Holt v.

Everall (4). I t is against public policy that a person should profit

through his or her own criminal act. I t was held in Amicable

Assurance Society v. Bolland (5) on that principle that the

assignees of a man who died through his own crime by the hands

of justice could not recover on a policy of insurance upon his

life. The policy must be read as subject to an implied exception

of the case where the insured dies by the hands of his wife. The

legal interest in the policy may be vested in the executors ; but

under the Married Women' s Property Act, they would be

trustees of the money for the wife: see Be Dash; King v.

Barley. (6) The Court will not allow her through other persons

to obtain a benefit which it is against public policy that she

should obtain. By the terms of the policy and the 11th section

of the Married Women's Property Act, the wife is the only

person interested in the policy money. The trust in her favour

cannot be said to have been performed. I t remains unperformed.

But the money cannot be recovered by her or any person suing

as her trustee, because the death of the husband was caused by

her criminal act. The case is similar in principle to the case

where a man insures his own life and then commits suicide

feloniously.

Sir Charles Bussell, Q.C., in reply.

Cur. adv. vult.

(1) 1 Mood. & Bob. 481. (4) 2 Ch. D. 266.

(2) 30 L. J. (Ch.) 511. (5) 4 Bli. (N.S.) 194.

(3) 4 E. & B. 243. (6) 57 L. T. (N.S.) 219.

1Q. B. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. 151

Dec. 8. LORD ESHEE, M.E. In this case the executors of the ' C. A.

will of James May brick in that capacity sue the defendants upon a 1891

policy of life insurance granted by them to the testator. James ~\ ~

Maybrick is dead, and the. defendants admit that during his v.

lifetime they granted him the policy ; but they insist that they RESERVE

are not liable to pay the sum insured to his executors, because ^"JJ^QJ^IQ^-

they would hold it in trust for the wife of James Maybrick, and

his death was occasioned by the criminal act* of his wife, that is

to say, she murdered him. ' They say that it.would be contrary

to public policy that under such circumstances they should be

compelled to pay this money to the plaintiffs, and therefore that

public policy excuses them from that which would otherwise be

the due fulfilment of their contract. No doubt there is a rule

that, if a contract be made contrary to public policy, or if the

performance of a contract would be contrary to public policy,

performance cannot be enforced either at law or in equi t y; but

when people vouch that rule to excuse themselves from the

performance of a contract, in respect of which they have received

the full consideration, and when all that remains to be done

under the contract is for them to pay money, the application of

the rule ought to be narrowly watched, and ought not to be

carried a step further than the protection of the public requires.

This policy of insurance is in a somewhat peculiar form, which

I suppose is of recent invention. I t does not state on the face

of it with whom it is made, but states that for the considerations

therein mentioned the defendants make the insured a member,

and promise that on his death the policy money shall be pay-

able to Florence Maybrick his wife, if then living, otherwise to

his legal personal representatives. I will first consider what the

legal effect of such a policy would be apart from the Married

Women's Property Act, and if no such act had been passed.

The contract is with the husband, and with nobody else. The

wife is no party to it. Apart from the statute, the right to sue

on such a contract would clearly pass to the legal personal

representatives of the husband. The promise is one which

could only take effect upon his death, and therefore it must be

meant to be enforced by them. The condition on which the

money is to become payable is the death of James Maybrick.

152 QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. [1892]

C. A. There is no exception in case of his death by the crime of any

1891 other person, not even by the crime of the wife. Therefore the

CLEAVEU condition expressed by the policy, as that on which the money

MUTUAL *

S

^ become payable, has been fulfilled. Consequently, so far,

RESEHVE

arj

(i jf

n 0

question of public policy came in, there would be no

FUND LI FE

U

. .

ASSOCIATION-, defence to an action against the defendants by the executors of

Lord Esher,M.R. James Maybrick. Apart from the statute, what would be the

effect of making the money payable to the wife ? I t seems to me

that as between the executors and the. defendants it would have

no effect. She is no party to the contract; and I do not think

that the defendants could have any right to follow the money

they were bound to pay and consider how the executors might

apply it. I t does not seem to me that, apart from the statute,

such a policy would create any trust in favour of the wife.

James Maybrick might have altered the destination of the

money at any time, and might have dealt with it by will or

settlement. If he had done so, the defendants could not have

interfered. I think that, apart from the statute, no interest

would have passed to the wife by reason merely of her being

named in the policy; and, if the husband wished any such

interest to pass to her, he must have left the money to her by

will or settled it upon her during his life, otherwise it would

have passed to his executors or administrators. The question

might arise how such a policy would have to be treated at law,

apart from the statute. Supposing such a policy were made in

favour of some person other than the person effecting the

insurance, and not being any of the persons named in s. 11 of

the Married Women's Property Actas, for instance, a nephew

or nieceand supposing that the person, in whose favour the

policy had been made, or to or upon whom the insurance money

had been left by will or settled, became the criminal cause of

the death of the insured, it would then be necessary to consider,

independently of the statute, what the effect of the policy

would be, and whether the insurance company could vouch

this doctrine of public policy as a defence to the action.

That the person who commits murder, or any person claiming

under him or her, should be allowed to benefit by his or her

criminal act, would no doubt be contrary to public policy.

1Q. B. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. 153

But this doctrine' ought not to be stretched beyond what is c. A..

necessary for the protection of the publ i c; and, if the matter 1891

can be dealt with so that such person should not be benefited, I CLEAVER ~

do not see any reason why the defendants in such a case should .., "

be allowed to say, though they might have received premiums RESERVE

perhaps for thirty years and still retained the same, that public ASSOCIATION.

policy forbade their paying the sum of money which they had

Lord E9her> M

.

R

,

contracted to pay. I t seems to me that this question of public

policy does not arise as between the executors and the defend-

ants. The question arises at a later stage. When the money is

in the hands of the executors, the question arises how, under the

circumstances, they must deal with it. If, in consequence of

the death of the insured having been caused by the crime of a

person in whose favour the policy is expressed to be made, or to

or upon whom the policy-money is left by will or settled, such

person is not entitled to insist on its being paid to him, but he

nevertheless claims the money from the executors, they may

then vouch the doctrine of public policy, and may say that by

reason of it such person has forfeited his or her right to the

money. What would be the consequence of t hat ? The exe-

cutors cannot be entitled to keep the money themselves. I t

seems to follow as a necessary result that they would hold it

as part of the estate of the testator. If the Married Women' s

Property Act had not been passed, or if the policy had made the

money payable to some person other than the insured's wife or

children, I should say that, on the true construction of the

policy, the only persons who could claim under it, and give a

valid receipt for the money insured, were the executors of the

insured; that as between them and the insurers the rule of

public policy referred to could have no application, and, there-

fore, that the insurers must pay the money to the executors, and

it would be for them to deal with it subject to the rules of public

policy; but the insurers would have nothing to do with the

application of the money after they had paid it. That would be

a matter entirely between the executors and any person, claiming

the money under any will or settlement made by the insured.

But this case must be considered further with reference to

the Married Women' s Property Act, 1882. Sect. 11 of that Act

VOL. I. 1892. M 2

154 QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. [1892]

C. A. provides that a policy of insurance effected by any man on his

1891 own life, and expressed to be for the benefit of his wife or of his

CLEAVEU children, or of his wife and children, or any of them, shall create

MUTUAL

a

*

r u s

t i

n

favour of the objects therein named, and the moneys

RESERVE payable under such policy shall not, so long as any object of the

ASSOCIATION, trust remains unperformed, form part of the estate of the insured

LordEsher.M.R. or be subject to his debts. Therefore, it is not provided that

such moneys shall never form part of the insured's estate, but

only that they shall not form part of his estate so long as any

object of the trust remains unperformed. That gives rise to t he

necessary implication, that, when no object of the trust remains

unperformed, the money is to. form part of his estate. Then

it is provided that " t he insured may, by the policy or any

memorandum under his hand, appoint a trustee or trustees of the

moneys payable under the policy, and, in default of any. such

appointment of a trustee, such policy shall, immediately on its

being effected, vest in the insured and his legal representatives

in trust for the purposes aforesaid." Under this provision, no

trustee having been appointed, the policy vests in the executors

who are trustees for the purposes of the trust in favour of the

wife, but only as long as the object of the trust remains unper-

formed. When the object of the trust no longer remains unper-

formed, the policy is to form part of the estate of the insured.

Suppose the wife had died before the husband, the defendants

could not have said that they would not continue the policy or

receive any more premiums, and that the policy was at an end.

I n that case the performance of the trust for the wife would have

become impossible. I take it that the proper reading of the

section is that, if the performance of the object of the trust has

become impossible, it must be treated as if it had been per-

formed ; and, therefore, there would in such case be no object of

the trust remaining unperformed. Applying the rule of public

policy to this, construction of the section, the wife here has

by her crime rendered the trust in her favour incapable of per-

formance. I t must, therefore, be treated as if it did not exist;

an object that cannot be performed cannot, for the purposes of

the section, be said to remain unperformed. Then, by necessary

implication, according to the section, the policy forms part of

1Q. B. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. 155

the insured's estate. As I have said, the rule of public policy is C. A.

not to be carried further than is necessary to ensure its object. 1891

On this construction of the section, it is unnecessary, under these CLEAVER

circumstances, to vouch the rule as between the executors and the ^i

v

^

UAh

defendants. The defendants must pay the money to the execu- RESERVE

T 1' UNDLIFE

tors, and then it will be for the executors to deal with it according ASSOCIATION.

to their duty as executors. They would be trustees of it for the LordEsher.M.R.

wife if she had not forfeited i t ; but her interest being forfeited,

it forms part of the insured's estate. If there are creditors, it

will go to them so far as may be necessary to satisfy their

claims. If anything is left, it will go to t he children of the

insured if there are any. The rule of public policy in such a

case prevents the person guilty of the death of the insured, or

any person claiming through such person, from taking the

money; but t he children would not claim through the mother,

but through the father. What is there against public policy

in such a result ? I think that, if the Court were to deprive the

children of the insured, who do not claim through the mother, of

the insurance-money under such circumstances, on the ground of

public policy, it would be a gross injustice. Any one claiming

through the wife is shut out by the rule of public policy ; so t hat

any assignee from her, or other person claiming through her,

cannot recover the money; but the rule of public policy does

not apply as between the executors representing the estate of

the insured and the defendants, and, therefore, their rights and

liabilities must be governed by the contract. That contract

does not make any exception in the case of the death of t he

insured being caused by the crime of any other person. Conse-

quently, I think that the suggested defence fails so far as the

executors of the insured are concerned. So far as regards the

assignee claiming through the wife, he has no title, and has not

made out his claim. For these reasons, I think that the decision

of the Divisional Court was wrong, and that the appeal should be

allowed.

FKY, L. J. Of the questions stated by the order of the master

in this .case one only has been argued before usnamely,

whether the murder of James Maybrick by his wife Florence, if

M 2 2

156 QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. [1892]

C. A. proved, would afford a defence to this action brought by the exe-

1891 cutors of James Maybrick. This question has been answered in

CLEAVEH the affirmative by the Divisional Court, and the judgment has

MUTUAL t een maintained before us by the same line of argument as was

BESERVE adopted by the Court, which is shortly as follows: The executors

FUND LI FE

A J

.

J

ASSOCIATION, of James Maybrick, it is said, are suing as trustees for Florence,

Fry, L.J. and can have no better title than their cestui que t rust : it is

against public policy to allow a criminal to claim any benefit by

virtue of his crime; she is, therefore, disentitled to claim the

proceeds of the policy in question, and the executors, who are

her trustees, are equally disentitled. This line of argument

appears to me equally untenable whether there be or be not such

a principle of public policy as that stated. If there be not, there

is no objection to the action; if there be, it disqualifies Florence

Maybrick from asserting that she is the cestui que trust of the

executors, and negatives the proposition that the plaintiffs are

suing for her benefit. They may be suing for their own benefit

or for the benefit of the estate of the deceased or of some other

person; but if the principle be valid, they cannot possibly be

suing for her benefit.

These observations are to my mind sufficient to dispose of

the case; but, considering its importance and the fulness with

which it has been argued, I shall descend somewhat more

on detail. The principle of public policy invoked is in my

opinion rightly asserted. I t appears to me that no system

of jurisprudence can with reason include amongst the rights

which it enforces rights directly resulting to the person asserting

them from the crime of that person. If no action can arise from

fraud, it seems impossible to suppose that it can arise from

felony or misdemeanour. , I t may be that there is no authority

directly asserting the existence of the principle; but the decision

of the House of Lords in Fauntleroy's Case (1) appears to proceed

on this principle, and to be a particular illustration of it. This

principle of public policy, like all such principles, must be

applied to all cases to which it can be applied without reference

to the particular character' of the right asserted or the form of its

assertion. In Fauntleroy's Case (1) it was held to prevent the

(1) 4-Bli. (N.S.) 194.

1Q. B. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. 157

assignees of a forger from claiming the benefit of a policy on his C. A.

death at the hands of justice by reason of his forgery. I t would 1891

equally apply, it appears to me, to the case of a cestui que trust CLEAVEU

asserting a right as such by reason of the murder of the prior jf

UT

'

UAL

tenant for life or of the assured in a policy: and it must be so KKSEBVB

. . . T i i F UND L I F E

far regarded in the construction of Acts of Parliament that ASSOCIATION.

general words which might include cases obnoxious to this FryTiTj-

principle must be read and construed as subject to it.

James Maybrick insured his life in the policy in question in

the year 1888, and by the proposal which was made part of the

policy he expressed the .policy to be effected for the benefit of

his wife, and in the policy itself she is named as the payee of the

policy-moneys in the event, which happened, of her surviving

her husband. Independently of the Married Women's Property

Act, 1882, the effect of this transaction was, in my opinion, to

create a contract by the defendants with James Maybrick that

the defendants would, in the event which, has occurred, pay

Florence Maybrick the 2000Z. assured; it would be broken by

non-payment to her; but the cause of action resulting from such

breach would vest in the executors of the assured, and not in the

payee. She was, independently of the statute, a stranger to the

contract; it might have been put an end to by the contracting

parties without her consent, and the breach of it would have

given her no cause of action against any one.

The 11th section of the Married Women' s Property Act, 1882,

deals with policies like the present, effected for the expressed

benefit of a wife, and, amongst other things, contains these

alternative provisions. I t enables the insured to appoint a

trustee or trustees of the moneys payable under the policy ; in

default of such appointment, it provides that the policy shall vest

in the assured and his legal personal representatives. I t is impos-

sible to consider the insertion of the name of Florence Maybrick

in the policy as the nomination of her as trustee for herself;

there is no nomination of any other t rust ee; consequently the

statute applied, and, in spite of her nomination as payee, vested

the policy in James Maybrick and his legal personal represen-

tativesnamely, the plaintiffs. The section in question goes

further, and declares the trusts on which such a policy is to be

158 QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. [1892]

0. A. held. According to its language, the effecting of this policy

1891 created a trust in favour of the object namedthat is, Florence

CLEAVEK Maybrickand the section enacted that the moneys payable

MUTUAL under it should not, so long as any object of the trust remained un-

KESERVE performed, form part of the estate of the insured. Now, the trust

FUND LI FE

r r

ASSOCIATION, thus created by statute, and the language of the statute creating

Fry, L.J. it, must, in my opinion, be both subject to the principle of public

policy which I have statednamely, the trust is one which can-

not be enforced by a murderess of her husband, and the language

of the statute must be read as if 'it contained an exception of

such a case. Consequently the trust which the statute was in-

tended to create has either never arisen or it has, by the act of

the cestui que trust, become incapable of enforcement. If the

executors of the insured were in such a case as the present to

refuse to sue the office, it is inconceivable to me that the mur-

deress could maintain >a suit against them to enable her to use

their names; or,- in fact, that she could be allowed to sue in any

way in aCour t of Equity as cestui que trust of a fund which she

had created by her crime. - But if the executors are not trustees

for Florence Maybrick,-for whom are they' trustees?' 'This ques-

tion seems to admit of' an easy answer. Whenever' there is

property produced by the payments of A. which is held in trust

for B., and that-trust fails or is satisfied, a resulting trust arises

for A. or his estate. This resulting trust is recognised by the

section of the Act in question, because it takes the property out

of the estate of the insured so long as any object of the trust

remains unperformed: language which implies, if it does not

assert, that when no object of the trust remains to be performed

the policy-moneys form part of the estate of the insured. If it

be suggested that this view only removes the difficulty a step

further off, and that the possible right of the wife under her

husband's will or intestacy forms an objection to the action by

the executors, the reply is obviousthat the principle of public

policy must be applied as often as any claim ' is made by the

murderess, and will always form an effectual "bar to any benefit

which she may seek to acquire as the result of her crime. ' It

follows from the view which I -have expressed that I think it

needless to inquire what the particular trusts may be on which

1Q.B. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. 159

the convict's property is held by the administrator appointed C. A.

under the statute of 1870. He took only the property which 1891

Florence Maybrick had in the moneys in question ; and as she CLEAVEE

took nothing, in my judgment, by reason of her crime, he takes MUTUAL

nothing likewise. RBSEBVB

. FUND LI FE

I t may be argued that having regard to the fact that ASSOCIATION.

Mrs. Maybrick is the prime object of the insurance, and that Fry, L.J.

she is named on the face of the policy as payee, the contract

of insurance must be taken to imply an exception of the case of

the death of the insured when caused by the crime of the person

so named; and it is suggested that Fawitleroy's Case (1) in the

House of Lords supports this contention. This argument does

not appear to me to be tenable. The policy is effected under,

and therefore affected by, a statutory enactment, the effect of

which in the present case is to vest the policy in. the executors

of the insured as trustees in the event of Mrs. May brick's being

entitled to claim in trust for her, and in every other event in

trust for the estate of James Maybrick;just in' the same way as

if before the statute a policy had been' t aken out by James

Maybrick, and he had by a separate instrument declared the like

trusts of it. Now, it is to my mind illogical to make the crime

of one cestui que trust a bar to the claim of another, or of the

trustees for that other cestui que t rust ; and if the supposed

defence were to prevail we should so hold. If Mrs. Maybrick

had inflicted a mortal, but not immediately fatal, wound on her

husband, had then committed suicide, leaving him surviving,

and his executors had claimed on his death, it appears to me

that the crime which caused his death would have furnished no

defence. In a word, I think that the rule of public policy should

be applied so as to exclude from benefit the criminal and all

claiming under her, but not so as to exclude alternative or inde-

pendent rights. In Fauntleroy's Case (1) the plaintiffs were the

assigns of the criminal, and were claiming through him. I n the

present case the plaintiffs are the assigns in law of the innocent

husband, and are claiming through him. The authority, there-

fore, of that case goes to shew that neither Florence Maybrick

nor the administrator of her estate, who claims through her, can'

(1) 4 Bli. (N.S.) 194.

160 QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. [1892]

C. A. t ake any benefit. But t hat appears to me t o t hrow no i mpedi -

1891 ment i n t he way of a sui t by t hose who cl ai m wi t h clean hands

OLEAVEU t hemsel ves and as assigns of t he i nnocent i nsured. I n a word,

MUTUAL ^ appears t o me t hat t he cri me of one person may pr event t hat

RESERVE person from t he assertion of what would otherwise be a r i ght , and

FUND LIEE . .

. ASSOCIATION, may accelerate or beneficially affect the rights of third persons,

Fry, L.J. but can never prejudice or injuriously affect those rights. I n

my opinion, therefore, public policy prevents Florence Maybrick

from asserting any title as cestui que trust of this fund, and

thereby brings into operation the resulting trust in favour of the

estate of the insured, and so enables the executors to maintain

an action as plaintiffs without any taint derived from the crime

committed by Florence Maybrick.

LOPES, L.J. The action is brought by the personal represen-

tatives of James Maybrick, and the question we have to consider

is whether the crime of his wife, Florence Maybrick, incapacitates

them from recovering upon the policy of insurance effected by

the husband with the defendants the amount of the policy-money,

which, by the terms of the policy, is made payable to the wife if

she survive the husband. The contract was between the hus-

band and the defendants. The husband died by the criminal

act of the wife. The right of action upon the contract passes to

the legal personal representatives upon his death. I do not

doubt that the principle of public policy would prevent the wife

from recovering the amount of the policy money from them, and

so reaping benefit from her crime; because no trust can be

enforced which contravenes the law. The simple answer to the

defence set up is that the executors are entitled to say that they

are suing for the benefit of the estate of the deceased husband;

and, therefore, no question of public policy arises. I t appears

to me clear that such would have been the case, if the Married

Women' s Property Act, 1882, had not been passed. I agree with

the Master of the Eolls and Lord Justice Fry, that the effect of

the section of that Act which has been referred to is to create

a resulting trust in favour of the husband's estate which takes

effect when by reason of the crime of the wife the trust in her

favour becomes incapable of being performed in consequence of

1Q. B. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION. 161

the rule of public policy. The trust in favour of the wife must C. A.

then be regarded as struck out, and, that being so, a resulting 1891

trust in favour of the husband's estate arises. For these reasons, CLEAVER

I agree that the appeal should be allowed. '

M

*

Appeal allowed. ]?UND LIFE

ASSOCIATION.

Solicitors for the plaintiffs: Sh'arpe, Parkers, & Co., for Cleaver,

Eolden, & Co.

Solicitors for the defendants: Robinson & Stannard.

E. L.

RADCLIFFE v. BARTHOLOMEW. Nov. 9.

JusticesJurisdictionTime within which Complaint must be made

12 & 13 Vict. c. 92, s. 14.

By s. 14 of the Act for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (12 & 13

Vict. c. 92), every complaint under the provisions of the Act is to be made

" within one calendar month after the cause of such complaint shall arise."

On June 30 an information was laid against the appellant in respect of an act

of cruelty alleged to have been committed by him on May 30. An objection

to the jurisdiction of the justices having been taken, on the ground that the

complaint had not been made within one calendar month after the cause of

complaint had arisen :

Held, that the day on which the alleged offence was committed was to be

excluded from the computation of the calendar month within which the com-

plaint was to be made; that the complaint was therefore made in time, and

the justices had jurisdiction to hear the case.

CASE stated by justices.

An information under 12 & 13 Vict. c. 92, s. 2, was laid on

June 30, 1891, by the respondent against the appellant, charging

him with ill-treating certain sheep on May 30, 1891. By s. 14

of that Act it is enacted that " every complaint under the provi-

sions of this Act shall be made within one calendar month after

the cause of such complaint shall arise." At the hearing before

the justices a preliminary objection was taken on behalf of the

appellant that, as the offence was alleged to have been com-

mitted on May 30 and the information was not laid until June 30,

the complaint had not been made " within one calendar month "

after the cause of complaint had arisen, and that therefore the

justices had no jurisdiction to hear the case. The justices

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- University of Ghana Law JournalDocument15 pagesUniversity of Ghana Law JournalBernard Nii Amaa100% (1)

- Yu Vs PaclebDocument2 pagesYu Vs PaclebMarie Bernadette Bartolome100% (2)

- Bombay High Court Original Side FormsDocument147 pagesBombay High Court Original Side FormsAbhishek Sharma100% (2)

- COMMERCIAL LAW I (SALE OF GOODSDocument37 pagesCOMMERCIAL LAW I (SALE OF GOODSNaana Awuku-ApawPas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument12 pagesCase StudyShreejana Rai100% (1)

- Case BriefDocument24 pagesCase BriefPritha BhangalePas encore d'évaluation

- Notes ContractDocument50 pagesNotes ContractS S PPas encore d'évaluation

- Fernandez VsDocument56 pagesFernandez VsfirstPas encore d'évaluation

- Restrictive Covenants in Employment ContractsDocument15 pagesRestrictive Covenants in Employment ContractsAnshu SethiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Handled by Atty. Elman Is Not Intended To Replace Your Books and Major References. God BlessDocument10 pagesHandled by Atty. Elman Is Not Intended To Replace Your Books and Major References. God BlessCharlotte GallegoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gabin v. Villanueva, CA, 51 OG 5749Document3 pagesGabin v. Villanueva, CA, 51 OG 5749Cza PeñaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jawapan Final LAWDocument9 pagesJawapan Final LAWNur Fateha100% (1)

- Banker and Customer RelationshipDocument24 pagesBanker and Customer RelationshipNana OpokuPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Economic TortsDocument7 pagesNotes On Economic TortsMARY ESI ACHEAMPONGPas encore d'évaluation

- CUTTER V POWELL CONTRACT DISPUTEDocument11 pagesCUTTER V POWELL CONTRACT DISPUTEEbby FirdaosPas encore d'évaluation

- Law Notes Vitiating FactorsDocument28 pagesLaw Notes Vitiating FactorsadelePas encore d'évaluation

- The Rule of Last OpportunityDocument4 pagesThe Rule of Last Opportunityashwani kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Inevitable Accidents With The Case Law Holmes VDocument2 pagesInevitable Accidents With The Case Law Holmes VAnonymous snwawPWqPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Rights Versus Mineral RightsDocument7 pagesLand Rights Versus Mineral RightsMordecaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of Evidence Notes MLTDocument15 pagesLaw of Evidence Notes MLTKomba JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Land AssignmentDocument7 pagesLand AssignmentDiana MillsPas encore d'évaluation

- Amalgamated Investment and Property Co LTD V John Walker & Sons LTDDocument12 pagesAmalgamated Investment and Property Co LTD V John Walker & Sons LTDthinkkim100% (1)

- Tenure and EstatesDocument2 pagesTenure and EstatesAdam 'Fez' Ferris100% (2)

- Conflict of Law NotesDocument11 pagesConflict of Law Notesfarheen haiderPas encore d'évaluation

- Midland Bank Trust Co LTD and Another V Green (1981) AC 513Document20 pagesMidland Bank Trust Co LTD and Another V Green (1981) AC 513Saleh Al Tamami100% (1)

- Intention To Create A Legal RelationshipDocument1 pageIntention To Create A Legal RelationshipShalim JacobPas encore d'évaluation

- AMPONSAH V AMPONSAHDocument4 pagesAMPONSAH V AMPONSAHNaa Odoley OddoyePas encore d'évaluation

- Law of Torts - KLE Law Academy NotesDocument133 pagesLaw of Torts - KLE Law Academy NotesSupriya UpadhyayulaPas encore d'évaluation

- The - Cape - Brandy - Syndicate - V - The - Commissioner Inland RevenueDocument19 pagesThe - Cape - Brandy - Syndicate - V - The - Commissioner Inland RevenueNoel100% (1)

- Privity of Contract in Indian LawDocument12 pagesPrivity of Contract in Indian LawR100% (1)

- Mere Silence Is No FraudDocument3 pagesMere Silence Is No FraudKalyani reddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Case List - Mid TermDocument9 pagesCase List - Mid TermGhanashyam DevanandPas encore d'évaluation

- The Queen v. Flattery (1877) 2 Q.B.D. 410Document4 pagesThe Queen v. Flattery (1877) 2 Q.B.D. 410Bond_James_Bond_007100% (1)

- Privity of Contracts ExplainedDocument6 pagesPrivity of Contracts ExplainedShashank Surya100% (1)

- Uganda Christian University, Mukono Faculty of Law Family Law Ii Reading List and Course OutlineDocument11 pagesUganda Christian University, Mukono Faculty of Law Family Law Ii Reading List and Course OutlineKyomuhendoTracyPas encore d'évaluation

- Remoteness of Damages: Meaning and ConceptDocument12 pagesRemoteness of Damages: Meaning and ConceptNamrata BhatiaPas encore d'évaluation

- MischiefDocument8 pagesMischiefKritika GoyalPas encore d'évaluation

- Customary Laws in TanzaniaDocument7 pagesCustomary Laws in TanzaniaKAPIPI TV100% (1)

- Fuji Finance v Aetna Life Insurance Co LtdDocument21 pagesFuji Finance v Aetna Life Insurance Co LtdKirk-patrick TaylorPas encore d'évaluation

- Advocate's Lien: A Critical Review of The Stance in IndiaDocument27 pagesAdvocate's Lien: A Critical Review of The Stance in IndiaApoorvnujsPas encore d'évaluation

- Hickman V Kent or Romney Marsh Sheepbreeders' Association (1915)Document4 pagesHickman V Kent or Romney Marsh Sheepbreeders' Association (1915)Bharath SimhaReddyNaiduPas encore d'évaluation

- Premachandra and Dodangoda v. Jayawickrema andDocument11 pagesPremachandra and Dodangoda v. Jayawickrema andPragash MaheswaranPas encore d'évaluation

- State of Kerala v. M.A. Mathai: Cases - Voidable Contracts Case Name Citation JudgementDocument4 pagesState of Kerala v. M.A. Mathai: Cases - Voidable Contracts Case Name Citation JudgementAishwarya ShankarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lachhman Das and Anr V, Mt. Gulab Devi-1Document14 pagesLachhman Das and Anr V, Mt. Gulab Devi-1Atul100% (1)

- Rights and Duties of Buyer and SellerDocument4 pagesRights and Duties of Buyer and SellerGarvit MendirattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Labour Law ContinuationDocument15 pagesLabour Law Continuationيونوس إبرحيم100% (1)

- Indemnity and Guarantee AssignmentDocument5 pagesIndemnity and Guarantee AssignmentShayan KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Caparo Industries V DickmanDocument47 pagesCaparo Industries V DickmanGeni FranzisPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract Act, 1872Document68 pagesContract Act, 1872Vidhi Vidhyavan100% (1)

- CONFLICTSDocument4 pagesCONFLICTSJon SantiagoPas encore d'évaluation

- In Re New British Iron Company, (1898) 1 Ch. 324Document9 pagesIn Re New British Iron Company, (1898) 1 Ch. 324Jikku Seban GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Tort LawDocument7 pagesTort LawKetisha AlexanderPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 5 Intention To Create Legal RelationDocument7 pagesChapter 5 Intention To Create Legal RelationZuhyri MohamadPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter One. Meaning, Nature and Classification of Law. Meaning and Importance of Legal MethodDocument69 pagesChapter One. Meaning, Nature and Classification of Law. Meaning and Importance of Legal MethodRANDAN SADIQPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter-Iv: R. V. ArnoldDocument24 pagesChapter-Iv: R. V. ArnoldvivekPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 4 Duty of Disclosure Materiality of Facts and MisrepresentationDocument19 pagesUnit 4 Duty of Disclosure Materiality of Facts and MisrepresentationIsrael KalabaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1894 (EC-16) Nordenfelt V Maxim Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Co LTD (Restrained of Trade)Document2 pages1894 (EC-16) Nordenfelt V Maxim Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Co LTD (Restrained of Trade)Mehreen AkmalPas encore d'évaluation

- Blog - Ipleaders - in - Indian Evidence Act Extent and ApplicabilityDocument11 pagesBlog - Ipleaders - in - Indian Evidence Act Extent and Applicabilityindian democracyPas encore d'évaluation

- School of Law Makerere UniversityDocument15 pagesSchool of Law Makerere UniversityNathan NakibingePas encore d'évaluation

- Manager, ICICI Bank V Prakash Kaur and OrsDocument10 pagesManager, ICICI Bank V Prakash Kaur and Orsarunav_guha_royroyPas encore d'évaluation

- West Wake Price & Co V ChingDocument15 pagesWest Wake Price & Co V ChingAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Law Firm Strategies for the 21st Century: Strategies for Success, Second EditionD'EverandLaw Firm Strategies for the 21st Century: Strategies for Success, Second EditionChristoph H VaagtPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights: Previous Year's MCQs of Tripura University and Answers with Short ExplanationsD'EverandHuman Rights: Previous Year's MCQs of Tripura University and Answers with Short ExplanationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Going for Broke: Insolvency Tools to Support Cross-Border Asset Recovery in Corruption CasesD'EverandGoing for Broke: Insolvency Tools to Support Cross-Border Asset Recovery in Corruption CasesPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1: Topic 2: Sales Force CompositeDocument5 pagesModule 1: Topic 2: Sales Force CompositeAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Banking NotesDocument21 pagesBanking NotesAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1: Topic 1: Nature of ProductionDocument2 pagesModule 1: Topic 1: Nature of ProductionAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Crown v. CeyDocument14 pagesThe Crown v. CeyAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Banking NotesDocument21 pagesBanking NotesAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Lennox Linton V AG of Antigua and BarbudaDocument51 pagesLennox Linton V AG of Antigua and BarbudaAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Minority Shareholder Protections in the Commonwealth CaribbeanDocument44 pagesMinority Shareholder Protections in the Commonwealth CaribbeanAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Feasey V Sun Life AssuranceDocument64 pagesFeasey V Sun Life AssuranceAisha Miller100% (1)

- West Wake Price & Co V ChingDocument15 pagesWest Wake Price & Co V ChingAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Philosophy of Human RightsDocument25 pagesThe Philosophy of Human RightsAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Insurance Policy DisputeDocument3 pagesInsurance Policy DisputeAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Elcock V Johnson (1949) 2 All E.R. 381Document11 pagesElcock V Johnson (1949) 2 All E.R. 381Aisha Miller100% (2)

- Best Buds LTD V Garfield Dennis PDFDocument6 pagesBest Buds LTD V Garfield Dennis PDFAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Policy and InsurabilityDocument12 pagesPublic Policy and InsurabilityAisha MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Error . Charles John Manning And: Heinonline - 9 Eng. Rep. 766 1694-1865Document10 pagesError . Charles John Manning And: Heinonline - 9 Eng. Rep. 766 1694-1865Aisha Miller100% (1)

- Oblicon DigestsDocument10 pagesOblicon DigestsPapo ColimodPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 3 - 1Document15 pagesWeek 3 - 1Ngân Hải PhíPas encore d'évaluation

- Judge Murphy's DecisionDocument95 pagesJudge Murphy's DecisionDan LehrPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic v. Dignos-SoronoDocument11 pagesRepublic v. Dignos-SoronoSP ZeePas encore d'évaluation

- Randstad v. Wilson (Non-Compete 2008)Document3 pagesRandstad v. Wilson (Non-Compete 2008)gesmerPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is A CompanyDocument8 pagesWhat Is A CompanyManvi TomarPas encore d'évaluation

- 02 Perena v. ZarateDocument8 pages02 Perena v. ZaratePaolo Enrino PascualPas encore d'évaluation

- Juris Case Digests 2Document11 pagesJuris Case Digests 2Wresen AnnPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court: Sycip, Salazar and Associates For Petitioners. Office of The Solicitor General For RespondentDocument8 pagesSupreme Court: Sycip, Salazar and Associates For Petitioners. Office of The Solicitor General For RespondentMamerto Egargo Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Diskusi 1. D1-Anissa Asyahra-20.05.051.0253-Manajemen Keuangan 2Document9 pagesDiskusi 1. D1-Anissa Asyahra-20.05.051.0253-Manajemen Keuangan 2Anissa AsyahraPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Laws LL and LW 4-3-2015Document45 pagesCivil Laws LL and LW 4-3-2015KrishnaKousikiPas encore d'évaluation

- Hwy 417/i-385 Annexation MapDocument1 pageHwy 417/i-385 Annexation MapGabe CavallaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Damages in A Commercial Context TexasbarcleDocument94 pagesDamages in A Commercial Context TexasbarcleFilippe OliveiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Law As A Practise of CourtsDocument10 pagesLaw As A Practise of Courtsasmita_malviyaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Carbonell V Metrobank PDFDocument15 pages4 Carbonell V Metrobank PDFCla SaguilPas encore d'évaluation

- Cuaycong vs. CuaycongDocument6 pagesCuaycong vs. CuaycongAngelica AbalosPas encore d'évaluation

- Court upholds housing developer's claim against homeowner for exceeding approved building heightDocument30 pagesCourt upholds housing developer's claim against homeowner for exceeding approved building heightZairus Effendi Suhaimi100% (1)

- Aricles 29-35Document23 pagesAricles 29-35TinersPas encore d'évaluation

- Court rules annotation an encumbranceDocument2 pagesCourt rules annotation an encumbrancePaulo VillarinPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 110358 RobledoDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 110358 Robledomarkhan18Pas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Law of Nepal, Nepal Kanun YouTube ChannelDocument19 pagesEvidence Law of Nepal, Nepal Kanun YouTube ChannelDeepak DhakalPas encore d'évaluation

- Estacion Vs BernardoDocument20 pagesEstacion Vs BernardoMelissa AdajarPas encore d'évaluation

- Position and Rights of A Minor in Partnership Firm PDFDocument4 pagesPosition and Rights of A Minor in Partnership Firm PDFamritam yadavPas encore d'évaluation