Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Civil Square - Merdeka Square of Malaysia

Transféré par

Oliver JJ Tan50%(2)50% ont trouvé ce document utile (2 votes)

223 vues24 pagesMorphology and design of a civil square in an urban context.

Titre original

Civil Square- Merdeka Square of Malaysia

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentMorphology and design of a civil square in an urban context.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

50%(2)50% ont trouvé ce document utile (2 votes)

223 vues24 pagesCivil Square - Merdeka Square of Malaysia

Transféré par

Oliver JJ TanMorphology and design of a civil square in an urban context.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 24

LEGIBILITY OF HISTORICAL URBAN SQUARE IN SHAPING IMAGE OF THE

CITY: A CASE STUDY OF MERDEKA SQUARE, KUALA LUMPUR

Tan Jun Jie

Master of Architecture, School of Architecture, Building & Design, Taylors University, Subang Jaya, 47500, Malaysia

Abstract

Since Dutch and British colonial settlements in Malaysia during 18

th

until 20

th

century, few historical cities such as

Georgetown, Melaka, Ipoh and Kuala Lumpur were developed. Many of the unique and historic buildings, open spaces and

other township components have contributed in shaping the character of these cities. Padang is one of the elements found in

the heart of many historical urban square in Malaysia, introduced during British colonial. It is a huge green open space for

many social activities and also a ground of exercising nations right of assembly for democracy. However, many of these

padang are in the threat as the victims of the rapid urbanization in this day and age. This paper is a review on the significance

and role of a padang in the image of the city of Malaysia. Case study was selected as the main research methodology where a

historical urban square in Kuala Lumpur- Merdeka Square was selected due to its distinctive character and significance as a

padang in the city. With historical approach in the research, the role and the fate of the padang were identified on the basis of

its morphological, sociological characteristics and architectural meanings to the nation and general public. The paper revealed

Merdeka Square have been disrupted by the invasion of rapid development which resulted to the disappearance of its original

unique identity as a civic square due to the changes in its use. This paper also suggests that the padang and its surrounding

built environment convey various architectural meanings which lead to the image formation of a city.

Keywords: Legibility; Historical urban square; Padang; Image of the city; Merdeka Square

1.0 Introduction

A city without old places is like a man without memory (Vani, 2005). Many cities have quarters that play

an irreplaceable role in shaping an image for the city. For most of the time, public squares are contributing to part

of the citys charm and appeal, as their aesthetical and functional qualities are essential in shaping the citys image

and identity. Public square in a city acts as a breathing space for the urban dwellers to have their recreational

activities and social interactions. A public place also providing a place for exercising the right of assembly and

free speech, heartbroken communion and civic discussion which are important to participatory democracy and the

good life (Child, 2004).

In Malaysias development and urban form, the elements that commonly be seen are urban squares, parks

and public open spaces, which most of them are locally known as padang. Padang is a Malay word which means

a large field turfed with grass with an area bigger than a football pitch (Zalina and

Ismail, 2008). In British India,

padang was begun as esplanade and extended to South East Asia later on (Hoyt, 1993). Hoyt (1993) described

the padang as an expanse of green known as a large closely trimmed lawn alien to pre-colonial, equatorial Malaya.

During British Colonial. Padang was one of the most notable features found in front of British administrative

buildings that being used for parades on formal occasions.

In the decades of rapid development where city urbanisation and technological advancement are taking place,

many historic cities are being threatened. The new development will insist an irreversible transformation to the

physical and also visual image which causes loss of identity. Consequently, all features such as open spaces,

streets and traditional activities; attributes that give a city its unique character and provide the sense of belonging

to its community are continuously disappeared. Many of these spaces have gradually disappeared, including the

padang in many cities in Malaysia.

This research will look into the contribution of a padang in shaping the citys image. This research will

explores the physical qualities of a padang which relate to the attributes of history, identity, place attachment and

meaning of it to the mental map of the public. This leads to the definition of legibility, that physical and visual

quality of the objects which give it a high probability to evoke a strong image in urban observers (Lynch, 1960).

An image interpretation and use in the design will be then be focused in the research through literature reviews

and case study. Image interpretation is being reviewed in terms of history, local context, spatial identity, and how

surrounding activities affect the identity of the padang. In this research, historical padang namely Merdeka Square

in Kuala Lumpur was chosen as case study sites due to its uniqueness and importance.

1.1 Merdeka Square

Merdeka Square has been witnessing the growth and development of Kuala Lumpur specifically within

its vicinity. However Merdeka Square had undergone to a certain extent of transformation and make over. It is

one of the earliest padang created by the British in Malaya and known as the Padang Club Selangor formerly

(Federal Department of Town and Country Planning, 2005). It is located at the central of an old government

administration district, and parallel with the Gombak River and sited opposite to hillock area of Bukit Aman (Bluff

Hill), the location for National Police Department headquarters. The padang was originally a military ground for

the police and army throughout the British colony (Federal Department of Town and Country Planning, 2005).

Eventually it became the centre for sports and recreation for the British and the elites group, often complemented

by a clubhouse. Cricket and football were played on regular basis and the padang evolved as the social and

recreational centre while serving its civic duty as the administration hub.

The creation of this padang is not made simply of leftover space between buildings and parking lots. It

is rather strong organizing places about which buildings and other parts of the city of Kuala Lumpur take form,

involving the process which is similar to many squares in all around the world. It is such a simple yet a unique

public place and well preserved since its creation by the British way back in the 1884. There were a lot of

ceremonies and parade held on this padang. Simultaneously, under the influence of enthusiastic European

sportsmen, it became a playing field for cricket and other team games and was made into level sward. As its

function as a civic square grew, many government offices were built around or near it including Sanitary Board

(1890), the Post Office (1894), the High Court (1904), the Survey Department (1909), and the Public Works

Department (1920) (Federal Department of Town and Country Planning, 2005).

It soon became the first Merdeka Parade in 1957 upon Malaysias Independence (Amree, 2007). It

underwent change from an urban square to a modern urban square with injection of sophisticated infrastructures

and facilities (big screen television, majestic flag pole, with parking space and commercial allotment underneath)

by today's professionals of globalization era. The padang is almost a restricted area. It opens only during special

occasions and on Merdeka Celebrations.

1.2 Problem Statement

In Malaysia, the historical Jalan Sultan which located at the heart of Kuala Lumpur is facing the threat

where the new MRT development is taking place while there were demonstrations and oppositions occurred in

recent years (the Star, 2012). This is happening near the most prominent urban squares located they in addition,

happen to be in the historic areas which were designated by the local authority as conservation zones. The

historical part of the Kuala Lumpur is facing the threat when the pressure for development has taken its toll on

the limited open spaces in the city centre in recent years.

Following the trend of the concept of a European plaza or roof top garden, there are many projects to

upgrade open space especially the padang where pavement, pavilion and concrete stage is included at the central

end of the padang. Similar case goes to Merdeka Square where no one among the early pioneers of this part of

the city of Kuala Lumpur would have imagined that their much admired padang would one day be completely

dug up and an enormous underground car park and commercial outlets built under it. Indeed, the completion of a

massive concrete platform during the 1990s backed by a gigantic digital monitor, bulky concrete performance

stage and flanked by what is reputed to be the worlds tallest flag-pole has totally changed the character of this

historical site (Chandran, 2004).

With all the changes and transformations, the issue now is, whether image and identity of Kuala Lumpur's

Merdeka Square can withstand the process of change and whether the process of transformation, one way or

another affects the image of the city.

1.3 Research Question

The research question is as bellow;

1. How does the design of an urban square affects the citys image and identity?

1.4 Aim and Objectives

The main aim is to examine the legibility of historical padang as an open space in a city and its

contributions in shaping the image of the city.

1.4.1 Research Objectives

1. To explore the character of a padang in terms of its history, morphology, function and image.

2. To identify the role and architectural meanings of a padang in the formation of a citys image.

3. To examine the level of legibility of a padang from the perception of general public.

2.0 Literature Review

2.1. Legibility of Urban Squares as Public Open Space

Public urban square is an open space which commonly found in the heart of a town used for social and

economic exchange, community gatherings (Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2009).

Many researchers have tried to identify the criteria of the ideal and successful urban squares as a public open

space.

Access and Linkages

To be successful, a public square needs to be easy to get to and get through (Project for Public Space, 2009). In

the physical dimension, a high quality public open space should have a clear and easy access and movement

system (Gehl 2002). It could be attained by creating linkage as clear paths which connect each other and by

integration of transportation mode and land use, the present of landmark as orientation. Successful squares are

always easily accessible by foot. The best pedestrian walkway are linking with narrow surrounding streets, well-

marked crosswalks, timed lights for pedestrian, slow-moving traffic and transit stops nearby (Project for Public

Space, 2009).

Comfort and Safety

In psychological dimension, the criteria of a successful public open space is promoting comfort and safety

(Danisworo, 1989). Comfort includes perceptions about safety, cleanliness, and the availability of places to sit

the importance of giving people the choice to sit where they want is generally underestimated (Project for Public

Space, 2009). While in the Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) principles, few strategies

are set to encourage users of a building, park, or street to feel safe about their surroundings while dissuade

offenders from committing crimes. According to Moffat (1983), the six main concepts are territoriality,

surveillance, access control, image/maintenance, activity support and target hardening.

Greeneries and Amenities

To improve comfort relaxation, natural elements are important factor in public open space. It could be achieved

by placing tress along pedestrian path and sitting area (Gehl, 2002) that enhance pleasant experience and anticipate

unpleasant climate. Other than greeneries, a square should feature amenities such as bench or waste receptacle

that make it comfortable for people to use (Project for Public Space, 2009). While in highlighting specific

activities, entrances or pathways, good lighting should be integrated into the design. Temporary installations such

as public art can act as a great magnet for children of all ages to come together. Whether temporary or permanent,

a good amenity will set up a genial ground for social interaction (Project for Public Space, 2009).

Activities and Sociability

In urban environments, public spaces such as squares can serve as successful social spaces and can function as a

focus for different activities (Ferdous, 2013). Public open space is successful when it becomes a conducive place

for social interaction with a wide range of activities occur. According to Murat (2013), public squares has the

main contribution to the social interaction. Urban squares act like social catalysts to gather citizens together for

various reasons and activities. The way and context of this social interaction displays the local identity.

2.3. Legibility of Urban Square as a Civic Open Space

Civic open space is the representation of a nation civic pride and dignity, and in the case of Malaysia,

often reflects the local community they represent (Federal Department of Town and Country Planning, 2005).

Civic squares and plazas often containing statues or fountains and primarily paved, sometimes providing a setting

for important public buildings (Khalid, 2008).

Image and Identity

Historically, squares were the centre of communities, and they traditionally helped shape the identity of entire

cities (Project for Public Space, 2009). Image of a square often relate to its form at the first sight. A public squares

form is influenced by the surrounding environment. Even though the word square points out a form itself, a

public square can be in any form such as rectangle, square, circle, triangle or amorphous (Murat, 2013). A distinct

form of a civic square that closely ties to the great civic buildings located nearby, such as cathedrals, city halls, or

libraries is often shaping the image of many squares. Sometimes a fountain was used to give the square a strong

image (Project for Public Space, 2009). Think of the majestic Trevi Fountain in Rome or the Swann Fountain in

Philadelphias Logan Circle. Today, creating a square that becomes the most significant place in a citythat gives

identity to whole communitiesis a huge challenge, but meeting this challenge is absolutely necessary if great

civic squares are to return.

Sense of Enclosure

Camillo Sitte, in his work City Planning According to Artistic Principles (1889) emphasizes that the main

requirement of a square is the sense of enclosure. Enclosure is one of the perceptual organization principles of

the Gestalt psychology. Grouping is the fundamental concept of the Gestalt approach. People tend to group objects

that look similar and close to each other. Furthermore enclosure or closure helps us to perceive objects as a whole

(Murat, 2013). The easiest and straightforward way of creating enclosure is grouping buildings around a central

space. Other than group, another aspect that need to be considered is the height of the surrounding enclosure.

Urban design guidelines by the Scottish Government (2009) suggest that for a square, the minimum ratio of height

of the building to the width of the square is 1:6 to create a good sense of enclosure.

Visual Attractions

Visual attractions of a public open space could be reach by attractive building facade architecture and interesting

scene and details (Gehl, 2002). Sitte (1889) focuses on the visual appearance rather than the functionality. The

ideal morphological aesthetic criteria of the urban square including monuments that are placed on the perimeter,

existence of the elements of surprise, attractiveness of architectural faades, and concavity and aesthetic

pavement. Different research literatures also mention the importance of these physical features and corroborate

the following outcomes together with the inclusion of water features and fountains and presence of monuments

or sculptures (Lynch, 2007).

History

History of a public squares is importance for the citys identity and they usually reflect the collective values of

the community (Murat, 2013). According to Levy (2012), the main difference between a public park and a public

square is that on a square, citizens are not connected to manifestations of nature, but to the heart of urban culture,

history and memory. In the last few decades, many urban squares have lost their function and memory due to the

new development. Thus, it is important to reconsider and review urban public square design approaches in order

to sustain and improve our existing squares or create enjoyable new ones.

2.4 Legibility of Urban Square in Shaping Citys Image

Lynch (1960) had identified the five physical elements that will help shaping the identity and structure

of a city, which are (1) paths, (2) edges, (3) districts, (4) nodes, and (5) landmarks. Lynchs elements all together

provide a complete image of the city: districts are structured with nodes, defined by edges, penetrated by paths,

and sprinkled with landmarks . . . elements regularly overlap and pierced one another (Lynch, 1960). A highly

legible or imageable city will contain structures or areas which is remarkable, distinct that would invite greater

attention and participation from the public.

Historically, it is proven that the padang can become strong features or elements in shaping the image of the

cities. Plaza de Mayor in Madrid, Tiananmen Square in Beijing, Time Square in New York, Trafalgar Square in

London, Old Town Square in Prague, Piazza San Marco in Venice, Saint Peters Square in Vatican City and Red

Square in Moscow are some examples of magnificent urban squares of the world. These urban squares seem to

have represented the cities that they are belong to, at the same time helping these cities to become sparkling places.

3.0 Methodology

Due to the complexity of the data collection and comprehensive investigation that needed to be done as

developed from the literature reviews, case study was chosen as the research methodology. Case study

methodology is ideal when a holistic and in-depth analysis is needed (Feagin, Orum and Sjoberg, 1991). Yin

(1994) defines the case study research method as an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary

phenomenon within its real-life context; when a contextual conditions needed to be studied deliberately. As

Merdeka Square is a historic open space that has gone through over hundred years of transformation, a historical

approach in the research is applied to study its morphology and comparison between history and contemporary

from various perspectives.

In this case study done in Merdeka Square, details from multiple sources of data are required to confirm the

validity of the processes (Yin, 1994). Case study is known as a triangulated research strategy (Tellis, 1997). Snow

and Anderson (1991) (cited in Tellis, 1997) asserted that triangulation can occur with data, investigators, theories,

and even methodologies. The integration in this paper is to combine the qualitative data in the form of texts or

images with the quantitative data in the form of numeric information. The qualitative research is to collect

explanatory data and then testing and verification by quantitative data collected.

The main part of the research is the qualitative research with case study done in Merdeka Square. Research

started by conducting pilot survey in Merdeka Square to identify the general design and activity pattern occurs in

the square. Site visit was done twice in the same day, being 12.30pm and 8.30pm on 17

th

November 2013.

Behavioural mapping and visual survey through photograph and diagrams are then carried out to identify how

variety and pattern of activities take place. The research will focus on image interpretation and use in the design

of urban squares. Image interpretation is looked at in terms history, morphology, function, image, and how

surrounding use of the surrounding affect the identity of Merdeka Square. An image interpretation is a process in

experiencing the environmental visual quality in the square.

In evaluating Merdeka Square, a framework that consists of 8 criteria including qualitative and quantitative

aspects as identified in the literature review is used. The 8 criteria are (1) access and linkages (2) comfort and

safety (3) greeneries and amenities (4) activities and sociability (5) image and identity (6) sense of enclosure (7)

visual attractions (8) history. The criteria are categorized into two sections. The first four criteria are relating to

first section: legibility of Merdeka Square as a public open space; the fifth criteria to eighth criteria is belonged to

second section: legibility of Merdeka Square as a civic open space. At the third section of the research: legibility

of Merdeka Square in shaping image of Kuala Lumpur, the frameworks used is referring to the five physical

elements as suggested by Lynch (1960) in his book The Image of the City: paths, edges, districts, nodes, and

landmarks, to examine its role as these five elements in the citys image.

Quantitative research is done through a survey to evaluate Merdeka Square from the perception of general

public. Photo survey is then designed and distributed online randomly. 30 respondents are collected after one

week of distribution of the photo survey online. Questions consist of three sections as follows: (1) perception

about the legibility of Merdeka Square as a public open space; (2) perception about the legibility of Merdeka

Square as a civic open space (3) perception about the legibility of Merdeka Square in shaping image of Kuala

Lumpur. The questions are set in statements about the square and the answers are measured in a five-point Likert

scale ranging from 1 for strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree, while 3 is considered to be the midpoint.

One open ended question was put at the last part of the questionnaire for respondents to give an overall perception

on design of Merdeka Square in terms of its role in shaping image of the city.

4.0 Results and Discussion

4.1 Access and Linkages

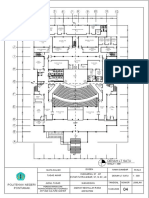

Map 1: Map of Merdeka Square showing location of bus stations and LRT station nearby. (Source: Google Map, 2013)

Merdeka Square is located right at the heart of the colonial district of Old Kuala Lumpur. The padang

therefore is surrounded by busy traffic network since the old days before Malaysias independence. Referring to

Map 1, it is now bounded by the Jalan Raja at the east and Jalan Kinabalu at the west. Jalan Raja which encircled

the padang and Lebuh Pasar at the east part are narrower for they were constructed the earliest than any other

areas in Kuala Lumpur. The padang also close to one of the main citys commercial district at Jalan Tuanku Abdul

Rahman and Jalan Masjid India. Along the street are three Kuala Lumpur remarkable landmarks, namely

Kompleks Dayabumi, the Railway Station and Offices and Sulaiman Building.

In term of public transportation, the padang is located near the Masjid Jamek LRT station which is within

350m walking distance. The two nearest bus station are the Dataran Merdeka, Jalan Raja Station and Bank Agro,

Lebuh Pasar Besar Station, which are within 100m and 160m walking distance respectively. Result from the

survey shows that majority people agree that the square has an easy accessibility by any mode transportation

including car, bus, LRT and walking (refer to Figure 1). This is because Merdeka Square is reachable by any

modes of transportation and the public transport stations are within walking distance.

Figure 1: Data collected from the photo survey. (Source: Author, 2013)

4.2 Comfort and Safety

Figure 2: Photograph showing backdrop of buildings and pedestrian pavement surrounding Merdeka Square. (Source: Author, 2013)

In term of safety environment, Merdeka Square has a good setting that it is surrounded by significant

colonial buildings which created a sense of ownership to the square. Around the padang is the well paved

pedestrian walkway and temporary steel railings which clearly demarcate the pedestrian from the green turfed

field (refer to Figure 2). Gathering spaces with water features and shrubs are located at the two ends: North and

South of the padang. With the clear designated pathways and common spaces, public access is being controlled

intangibly. Natural surveillance to the open square is achieved by the traffics and buildings around it.

As for the comfort aspect, the space is always clean where rubbish is hardly be seen during the site visits.

However, it is being found out that the square is lacking of shadings to promote walkability due to the lack of tall

shading trees. During night time, there is hardly any activities occur at the padang when no events are happening,

except the visitors who take a stroll there. The streets around the square are always in quiet (refer to Figure 3).

Figure 3: Photographs showing condition of Jalan Raja at 9.30pm. (Source: Author, 2013)

Although the padang and the buildings around it are lit up at night, sense of safety environment to the

visitors is still not promising. This phenomenon is reflected in the survey conducted. Result shows that there is no

major lead from the percentage of people feel safe and comfort over the percentage of people who disagree (Refer

to Figure 4). This shows that general public is still not convinced by the safety and comfort in Merdeke Square.

Figure 4: Data collected from the photo survey. (Source: Author, 2013)

4.3 Greeneries and Amenities

Figure 5: (a) left picture: Photograph showing plantations at the perimeter of the padang, (b) right picture: Photograph showing

plantations and water features at the northern part of the padang. (Source: Author, 2013)

The padang itself is a large field turfed with green. However, the taller greeneries which can provide

shadings are lacking. Tall palm trees are planted surround the boundary of the field with 10 meters apart from

each other (refer to Figure 5a); while the shrubs are only existing surround the water features at the northern part

(refer to Figure 5b). There is no seating or bench designated for the public and people are found sitting on the

steps or curbs around the water fountain.

At night, special lightings are only fitted and lighted up at some of the area (refer to Figure 6a): the flag

pole area, Sultan Abdul Samad Buildings and Tuscan column structure area (refer to Figure 6b). Other than that,

the padang is lighted up with ordinary street lights at the perimeter and a high power spot light irradiate over the

padang from the flag pole (refer to Figure 6c). Consequently, the quality of public realm is poor in terms of public

amenities and shadings.

Figure 6: (a) top picture: Photograph showing panaroma view the padang at 9pm. (Source: Author, 2013)

Figure 6: (b) bottom left picture: Photograph showing lightings at the Tuscan column structure, (c) bottom right picture: Photograph

showing spot light from the flagpole. (Source: Author, 2013)

4.4 Activities and Sociability

Figure 7: Photograph showing Merdeka Parade held at Merdeka Square on 31

st

August 2013. (Source: the Star, 2013)

Today, the padang is still the place for special events such as open air concerts, carnivals, starting or

finishing point for marathons. Parades and ceremonies such as independence celebration (Merdeka parade) is still

continuously taking place on the padang (refer to Figure 7). The flexible use of the padang for important civic

functions had led to the utilization of adjacent roads as part of the open spaces as a parade ground (Federal

Department of Town and Country Planning, 2005). In short, the padang was a centre for social life and a place to

promenade and place where the people communicate and unite.

However, it has become less significant when the major annual Merdeka parade shifted to grand avenue

of Putrajaya since 2003 (King, 2008) and the scale of the parade held at Merdeka Square these years were much

smaller than it used to be. The Sultan Abdul Samad Building was also left vacant when the court moved to

Putrajaya, the new administration centre of Malaysia (Wijnen, 2013). Except the tourists and a few number of

visitors, people were hardly be seen during the site visit, especially at night.

4.5 Image and Identity

Figure 8: Photograph showing bird eye view on Merdeka Square. (Source: Rhazlin, 2013)

The flat wide green turf which can be seen from a distance has become a backdrop and a floor for these

historical buildings. The square is always kept clean and the green turf is always well maintained. Its rectangular

form with surrounding buildings at the perimeter which features coherent architectural style, size and buildings

materials have created a distinctive image to the square. Water features are being found at the northern and

southern part of the padang. These features has led a good first impression to the visitors as shown in the result

from the survey done (refer to figure 9).

Figure 9: Data collected from the photo survey. (Source: Author, 2013)

These unique features that have historical value have shaped a strong character to the square which makes

it stands out from the other public squares, as agree by majority of the people from the survey done (refer to figure

10). For that reasons, Merdeka Square is successful in delivering the image and identity to the perception of

general public.

Figure 10: Data collected from the photo survey. (Source: Author, 2013)

4.6 Sense of Enclosure

Figure 11: Photograph showing surrounding buildings of Merdeka Square over the horizon. (Source: Author, 2013)

Referring to Figure 11, the horizontal expansiveness of vertical space: the Selangor Club (far left), St

Marys Church (at the far northern end) and the Secretariat (Bangunan Sultan Abdul Samad on the right) defining

the padang (King, 2008). Merdeka Square has walls- the colonial buildings and floor- the padang to provide the

sense of an enclosure and welcoming. It can be visually, socially, psychologically and physically accessible.

Figure 12: Data collected from the photo survey. (Source: Author, 2013)

However, the results from the survey done show that people are disagree that the square has a good sense

of enclosure (refer to Figure 12). By looking at the proportion of the height of the buildings to the width of the

square, the height of the surrounding enclosure is not convincing to create a good sense of enclosure. The padang

width is approximately 75 meters while the buildings are only two to three stories high (10-15 meters). The ratio

of the building height to the width of the square is now approximately 1: 6. This is below the minimum ratio as

suggested by urban design guidelines by the Scottish Government (2009), which is 1:7.

4.7 Visual Attractions

Figure 13: (a) top left picture: Bangunan Sultan Abdul Samad, (b) top right: 95-metre flagpole,

(c) bottom left picture: Tuscan column structure, (d) bottom right picture: Victoria Fountain (Source: Author, 2013)

The padang was the centre of social life for the European community and therefore it was surrounded by

many distinctive buildings which symbolizes the landmark of Kuala Lumpur, which most of them are still being

preserved till today. The building features include a coherent architectural style, size and buildings materials.

Moreover, it has been more than a decade it serves as a dominant ground in depicting one of the most prestigious

handsome building as well as important symbol of Kuala Lumpur, the Neo-saracenic style, Bangunan Sultan

Abdul Samad (refer to Figure 13a). It is a style that combined some features of Indian Muslim architecture with

Gothic and other European elements (King, 2008). At the southern end of the square is the 95-metre flagpole

(refer to Figure 13b). It is one of the tallest flagpole in the world, standing on top of a flat, round black marble

plaque. Tuscan column structure at the northern end of the padang is also making a good attraction to the public,

together with the fountain in front (refer to Figure 13c). It is one of the few structure that being lit up at night that

will look appealing to the visitors. The other attraction is the Victorian fountain which is located next to the

flagpole (refer to Figure 13d). These features has become strong visual attractions of the square, as agree by

majority of the people from the survey done (refer to Figure 14).

Figure 14: Data collected from the photo survey. (Source: Author, 2013)

4.8 History

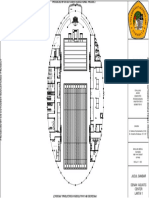

1887 1930 2007

Figure 15: The growth of Merdeka Square from 1887 to 2007. (Source: Zalina and Ismail, 2008)

Throughout almost 130 since its creation in 1884, Merdeka Square has witnessed many changes and

events. As can be seen in Figure 15, part of the padang at the both sides was occupied for several buildings and a

road. Bangunan Sultan Abdul Samad was built and occasionally it continued to be the centre of administrative

district. The most dramatic changes happened in the mid 1980s when it was completely dug up to accommodate

underground car park and commercial centres comprised of restaurants and business outlets known as Putra Plaza.

It was then roofed over and turned with many other landscape features on its top such as stage show, and gazebo,

and pedestrian walkways built around it. The underground plaza had, however, stopped operating after a big flood

hit Kuala Lumpur in 2003 (Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia, 2007). Now the padang is used as a marking point to

indicate the distance from any places in Malaysia to Kuala Lumpur city centre (Amree, 2007). It has become even

more easily spotted since the reputedly the worlds tallest flag pole was placed at the edge of it lawn.

Figure 16: (a) left picture: Merdeka Square in 1961, (b) right picture: Merdeka Square in 2013. (Source: HangPC2, 2013)

Today, half of the size of the padang and all new structures that were built later on surrounding are being

preserved from when it was created (refer to Figure 16). Mostly part of the Merdeka Square has been preserved

nicely and they are still in good condition which people still can trace back the original identity of the square.

However, they all had lost their original function which makes them now less significant. The urban culture where

it used to be the centre of administrative district and hold annual Merdeka parade in a large scale has disappeared.

This phenomenon is reflected through the survey conducted when the result shows that majority of the people do

not find the transformation of the square from the past is successful (refer to Figure 17). The memory of this space

in the local community is fading. Merdeka Square has, somehow, failed to reflect the collective values of the

Malaysian community.

Figure 17: Data collected from the photo survey. (Source: Author, 2013)

4.9 Kevin Lynchs The Image of the City: Five Elements

From the descriptive analysis, it can be summarized that the Dataran Merdeka and its surrounding area

may contribute as 5 elements of shaping the image of the city as follows:

Figure 18: Diagram of Merdeka Square- 5 elements of Kevin Lynchs Image of the City. (Source: Author, 2013)

Paths

Edges

Districts

Nodes

Landmarks

4.9.1 Paths

Paths here are the traffic roads. Pedestrian walkways are built along the roads. The padang is bounded

by two major roads: Jalan Raja at the east and Jalan Kinabalu at the west. Jalan Raja which encircled the padang

and Lebuh Pasar at the east part are narrower which less traffic is found. Intervening between the major and minor

roads has somehow created a unique but confusing path pattern to the Merdeka Square surrounding, where the

axiality and hierarchy in linkage are not clar.

4.9.2 Edges

Edges are defined by the rivers at the east: Gombak River and Klang River, as well as the main roads

with busy traffic surrounding the padang. Lack of river-crossing bridges and zebra crossing has stopped pedestrian

from the other nodes or districts to come over to Merdeka Square. Together with the heavy traffic roads that run

alongside the padang, Merdeka Square has formed a solid edge in between the neighbouring sites at the both sides

of it.

4.9.3 Districts

Each components surrounds the padang is architecturally and urbanistically associated with formal

compositional relationships in example the street that run along the padang, these two may form a district.

Merdeka Square itself, together with the Selangor Club, has formed a district where it is bounded by the paths

that alienate from the surroundings with the hard edges created insensibly. It has become a quiet district with less

pedestrian visiting throughout the day when there is no function on site.

4.9.4 Nodes

There is no node in the area of Merdeka Square. The nearest major nodes are the pedestrian nodes found

at Masjid Jamek LRT station and Central Market area along the riverside. The nodes at the opposite side of the

river have, however, left a quiet district at the other side of the river, which Merdeka square is located. It is now

only serve as passing point that allows people to come from many other commercial districts such as Jalan Masjid

India and Central Market.

4.9.5 Landmarks

The padang itself has become a landmark for Kuala Lumpur together with the Bangunan Sultan Abdul

Samad, 95-metre flagpole, and Daya Bumi tower. The smaller landmarks are the Selangor Club House. Being

dominance in its green characteristic and broad expanded flat open space, the padang is believed to operate as a

point of reference where from a distance, it can be observed from many angles and distances.

4.10 Summary

Table 1: Summary of all criteria for legibility of Merdeka Square as different architectural meanings and functions. (Source: Author, 2013)

Legibility Criteria Context

As

Public

Open

Space

Access and

Linkages

Well linkages with the road systems.

Good accessibility with public transportation.

Comfort and

Safety

Good setting and access control with proper pedestrian.

Lack of shadings, insufficient lightings at night.

Greeneries

and Amenities

Lack of tall vegetation.

Absence of designated seats.

Activities and

Sociability

Lack of social activities for locals constantly throughout the year.

Less significant as compared to previous years.

As

Civic

Open

Space

Image and

Identity

Good first impression visually.

Strong character with the layout and surrounding structures.

Sense of

Enclosure

Height of surrounding buildings is not enough.

Ratio of building height to width of square is too small.

Visual

Attractions

Strong visual attraction by the unique architecture and landmarks.

History Unsatisfying transformation.

Loosing of its original historical and sociological value.

In

Shaping

Citys

Image

(Kevin

Lynchs The

Image of the

City: Five

Elements)

As Paths Unique but confusing path pattern for users.

As Edges Hard edges formed by the bounded heavy traffic roads which break

pedestrian flow.

As Districts Quiet district with less pedestrian visiting.

Alienate from the other districts.

As Nodes No nodes existing on the padang area.

All nodes are far away from the square.

As Landmarks Serves as a prominent landmark for Kuala Lumpur.

Alignment of a number of good landmarks on site

As a padang, Merdeka Square has done substantially in terms of the physical built environment to serve

as a good open public space to the city. Connectivity including traffic and public transportation system is well

measured to ensure an easy accessibility to the site. However, when it comes to the user experience, some aspects

were not well considered such as the shadings from tall plantations, street amenities and good lighting during

night time. Activities that promote sociability is also lacking. These all aspects have additionally, made the square

a not cosy open space especially for the locals if they want to visit back for the second time. With only tourists

visiting at daily basis now, local sociability is missing.

Good setting with unique surrounding buildings have granted the square a strong character and identity

to the people. Merdeka Square has its irreplaceable value as a civic open space in Kuala Lumpur. However, it is

starting to loose from its original identity which now slowly turning into just a padang without activities that

chaining with the community. Citizens are no longer connected to the heart of urban culture, history and memory

of the historical civic square.

Figure 19: Data collected from the photo survey. (Source: Author, 2013)

The design of Merdeka Square has failed to represent the true identity of its belonging city, Kuala

Lumpur and this is reflected from the survey done (refer to Figure 19). What was being raised up as a major

concern is the true identity of Kuala Lumpur. As mentioned by one of the respondent from the survey, it was

surrounded by busy traffics, and it doesn't really show the unique of Malaysia culture.

When comes to analysing legibility of Merdeka Square in shaping image of the city, it is being found out

that its contribution as the five elements of a city (Kevin Lynch, 1960) were not being achieved successfully. As

the major component of the square and also to the city, the padang is now being questioned its functionality and

its role in contributing a good image to the city, when only the surrounding buildings and historical value of the

place are taking up the role. The Merdeka Square does not shape any image of Kuala Lumpur by itself, but

through the buildings surrounding it, said by one of the respondents from the survey. Another respondent also

said that there is not much image given by the design, the image given by the Merdeka Square is by the historical

value of the place that been through in Malaysia shapes the image. Despite the strong support from the historical

value, the design of the padang is no longer legible to serve as a major element in shaping the citys image as the

time pass through. Meaning of the Merdeka Square in the citys image is diminishing slowly in the mental map

of the general public.

5.0 Conclusion

Stories of Dataran Merdeka have uncovered it significant contributions to the vibrant social cultural

formation and development of Kuala Lumpur city centre. However, after years of transformation, its consistency

as a huge prominent green open square in the heat of the busiest district in Kuala Lumpur is being questioned.

Confidently, it has a strong unique character reinforced by buildings of various architectural styles and premier

events at once. However, with the gradually alterations of planning layout and activity pattern, functionality of

the padang is also affected. From a recreational ground and place for public contemplation, the padang has been

transformed into alienated district that only work well as a tourism spot.

The reviews also find that the legibility of an urban square in shaping city image does not stand on its

own, but because of strong character of surrounding elements and historical value of the place. It is hoped that

this finding might deliver a new perspective for the town planners and landscape architects to address for all

heritage conservation works to conserve the heritage values and also to identify role of the padang in the city. It

can be concluded that the padang and its surrounding area are conveying various role and architectural meanings

to the city and they are all are essential elements for the citys image. However, these meanings of Merdeka

Square to the mental map of the public is now weakening.

The findings implies that identity of a place is a chain connecting different elements, and the disturbance

of one element will affect all others. Inappropriate design and development in the city may be disturb the whole

urban environment. The changes and loss of original functionality which marked the character of a city will

directly weaken the place identity and memory of the place to the nation. This syndrome should be cured as they

will lead to the loss of place meaning. In response to this, the needs of conveying a firm framework for sustaining

valuable historical places within the city should become greatly important in town planning and urban design

practices.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my gratitude and many thanks to Dr. Roya Shokoochi for her guidance and

constant supervision as well as for providing necessary information regarding the research and also for her support

in completing this research paper. I would like to also thank to whom I had conversations with, and provided me

with many precious information.

References

Amree Ahmad. (2007). Padang banyak melahirkan jaguh sukan. Akhbar Kosmo. 19

th

August 2007. p.12.

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (2009). Urban Squares. Healthy Spaces & Places.

Australia. Retrieved from http://www.healthyplaces.org.au/site/urban_squares_full_text.php

Chandran, J. (2004). The padang; Kuala Lumpur in Kuala Lumpur; corporate, capital, cultural cornucopia. Arus

Intelek Sdn.Bhd. pp. 117,118 & 119.

Child, M.C. (2004).Squares: A public place design guide for urbanists. USA. University of New Mexico

Press.

Danisworo (1989) Konsep Peremajaan Kota, Institut Teknologi Bandung.

Feagin, J., Orum, A., & Sjoberg, G. (Eds.). (1991). A case for case study. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North

Carolina Press.

Federal department of Town and Country planning, Peninsula Malaysia. (2005). Open spaces in Urban

Malaysia. Ministry of Housing and Local Government Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. pp. 15-39.

Ferdous, F. (2011, May). The morphological evolution of the Bazaar Streets: A configurational analysis of

the urban layout of Dhaka City. Paper presented at the Environmental Design Research Association,

Chicago, IL.

Gehl, J. (2002). Public Space and Public Life City of Adelaide: 2002. Adelaide. Retrieved from

http://www.adelaidecitycouncil.com/assets/acc/Council/docs/public_spaces_and_public_life_report.pdf

HangPC2. (2013). KLs Dataran Merdeka Then & Now [Post 878] Message posted to

http://www.skyscrapercity.com/showthread.php?t=438753&page=126

Hoyt, S.H. (1993). Old Malacca. Oxford University Press. Kuala Lumpur. pp.67-68

Khalid, A. (2008). Toward a Sustainable Neighbourhood: The Role of Open Spaces. Archnet-IJAR (Vol.2).

King, R. (2008). Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya: Negotiating Urban Space in Malaysia. Singapore, NUS Press

Levy B. Urban Square as the Place of History, Memory, Identity, In: Dusica Drazic, Slavica Radisic, Marijana

Simu (eds), Memory of the City, Kulturklammer, Belgrade, 2012; pp 156-173.

Lynch, K. (1960). Image of the city. Cambridge, Mass. London, Eng.: MIT Press, repr. 2000.

Moffat. (1983). Model of First generation CPTED The Key Concepts; territoriality, surveillance (informal

and formal), access control, image/maintenance, activity programme support and target hardening.

Murat Z. Memluk (2013). Designing Urban Squares, Advances in Landscape Architecture, Dr. Murat Ozyavuz

(Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-1167-2, InTech, DOI: 10.5772/55826. Retrieved from

http://www.intechopen.com/books/advances-in-landscape-architecture/designing-urban-squares

Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia. (2007). Architectural heritage Kuala Lumpur. Maziza Sdn. Bhd. Kuala Lumpur

Project for Public Spaces (2009). 10 Principles for Successful Squares. Retrieved from

https://www.pps.org/reference/squaresprinciples/

Project for Public Spaces (2009). What Makes a Successful Place. Retrived from

https://www.pps.org/reference/grplacefeat/

Sitte, C., 1889 (2012). City Planning According to Artistic Principles [Reviewed by Thomas Sydney]. Retrieved

from http://architectureandurbanism.blogspot.com/2012/11/camillo-sitte-city-planning-according.html

Tellis, W. (1997). Application of Case Study Methodology. The Qualitative Report (Vol. 3, No. 3). Retrieved

from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR3-3/tellis2.html

The Scottish Government. (2009). Designing Streets: Consultation Draft: Part 6. Retrieved from

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2009/01/27140909/6

The Star. (2012). More than 1,000 gather in Jalan Sultan for Night of Activities. Retrieved from

http://www.thestar.com.my/story.aspx?file=/2012/2/8/central/10685748

The Star. (2013). Malaysians Celebrate 56

th

Merdela Day in patriotic fervor.. Retrieved from

http://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2013/08/31/merdeka-parade-nationwide.aspx

Wijnen, B. V. Merdeka Square. Retrieved from http://www.malaysiasite.nl/merdekaeng.htm

Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (Ed. 2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing.

Zalina, H. & Ismail, S. (2008). Role and Fate of Padang in Malaysia Historical Citites. Paper presented at: 5th

Great Asian Street Symposium 2008, Singapore 5-7 December 2008, National University of

Singapore.

Appendix A: Original Form of Photo Survey

Appendix B: Table of Data Collected from Survey

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Architectural floor plan layout for theater buildingDocument1 pageArchitectural floor plan layout for theater buildingZadha FaedhillahPas encore d'évaluation

- BMW Museum A Symbol of German Contemporary High-TechDocument14 pagesBMW Museum A Symbol of German Contemporary High-TechElizabeth MercyPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Architecture Research Final ReportDocument23 pagesAsian Architecture Research Final ReportTommy Tan75% (4)

- 5 Unusual Facts About Kengo Kuma PDFDocument9 pages5 Unusual Facts About Kengo Kuma PDFguuleedPas encore d'évaluation

- Concrete shell structures and their advantagesDocument10 pagesConcrete shell structures and their advantagesAbishaTeslinPas encore d'évaluation

- Piazz D'italiaDocument25 pagesPiazz D'italiaYeshu RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- 1973 Traditional Buildings of Indonesia Volume I Batak Toba PDFDocument54 pages1973 Traditional Buildings of Indonesia Volume I Batak Toba PDFNajli Eka RahmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading The Signs On Mosque ArchitectureDocument13 pagesReading The Signs On Mosque Architecturemiphz100% (1)

- Hares Seri SaujanaDocument10 pagesHares Seri SaujanaMohammad Akram KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Istiqlal Masjid, A Reflection of The Time of SukarnoDocument13 pagesThe Istiqlal Masjid, A Reflection of The Time of SukarnoMeiqi KohPas encore d'évaluation

- Xinsha Primary School's Innovative DesignDocument21 pagesXinsha Primary School's Innovative DesignAlya WaleedPas encore d'évaluation

- 31 Case Study Mode Gakuen Cocoon TowerDocument5 pages31 Case Study Mode Gakuen Cocoon TowerPrateekshaNathaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Review Buku Arsitektur Etnik: Pencerminan Nilai Budaya Dalam Arsitektur Di Indonesia.Document15 pagesReview Buku Arsitektur Etnik: Pencerminan Nilai Budaya Dalam Arsitektur Di Indonesia.Karlina Satrioputri100% (2)

- Mori TowerDocument14 pagesMori TowerHilal To100% (1)

- 'Natural' Traditions - Constructing Tropical Architecture in Transnational Malaysia and SingaporeDocument70 pages'Natural' Traditions - Constructing Tropical Architecture in Transnational Malaysia and SingaporeKurt ZepedaPas encore d'évaluation

- UTS BAHASA INGGRIS ARSITEKTURDocument1 pageUTS BAHASA INGGRIS ARSITEKTURHerryawan HerryawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Biography Teuku UmarDocument3 pagesBiography Teuku UmarAloel AmorPas encore d'évaluation

- S.R. Crown HallDocument2 pagesS.R. Crown HallAttarwala Abdulqadir Hashim FaridaPas encore d'évaluation

- Khan ShatyrDocument15 pagesKhan ShatyrMiftachKarimaHadi100% (1)

- A Case Study On Performance Based Design of Taipei 101 in TaiwanDocument12 pagesA Case Study On Performance Based Design of Taipei 101 in TaiwanAbhinav HiraPas encore d'évaluation

- CCTV Building Cantilever StructuresDocument8 pagesCCTV Building Cantilever StructuresSameer Ali100% (1)

- Arsitektur Neo ModernDocument28 pagesArsitektur Neo ModernErisa Weri NydiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bosowa University Makassar: Menara Phinisi UNM Building Project Architectural Engineering Group 3 NameDocument17 pagesBosowa University Makassar: Menara Phinisi UNM Building Project Architectural Engineering Group 3 Namealdy aldyPas encore d'évaluation

- ADB Lighting at Istana BudayaDocument3 pagesADB Lighting at Istana BudayaJay NeePas encore d'évaluation

- Lakeshore ApartDocument17 pagesLakeshore ApartmimiPas encore d'évaluation

- A4 Istana Budaya ReportDocument58 pagesA4 Istana Budaya Reportapi-289045350100% (1)

- ENGLISH GARDEN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTUREDocument31 pagesENGLISH GARDEN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTUREVernika AgrawalPas encore d'évaluation

- Dewan Tunku Canselor AnalysisDocument11 pagesDewan Tunku Canselor Analysisainos_alaiPas encore d'évaluation

- One World Trade Center - New YorkDocument16 pagesOne World Trade Center - New Yorkfebby khafilwaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Studi PresedenDocument10 pagesStudi PresedenHafidzZulfahmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Building Details Floor Plan: Night ViewDocument1 pageBuilding Details Floor Plan: Night ViewNur Shazwani WaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Pengantar Konteks Perkotaan: (Introduction To Urban Context) SyllabusDocument7 pagesPengantar Konteks Perkotaan: (Introduction To Urban Context) SyllabusNadya IrsalinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Beijing National Aquatics CenterDocument7 pagesBeijing National Aquatics Centerroxanao33Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hermitage HotelDocument10 pagesHermitage HotelBharata Hidayah AryasetaPas encore d'évaluation

- Riverside Museum Zaha HadidDocument13 pagesRiverside Museum Zaha HadidNitaNurhayatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Temporary ArchitectureDocument6 pagesTemporary ArchitectureMariah Concepcion100% (1)

- 30 ST Mary Axe - Abbas Riazibeidokhti PDFDocument18 pages30 ST Mary Axe - Abbas Riazibeidokhti PDFpuppyarav2726Pas encore d'évaluation

- Crown HallDocument15 pagesCrown HallnamrataPas encore d'évaluation

- Urban Renewal and ConservationDocument4 pagesUrban Renewal and ConservationDivya GorPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis Semiotik Budaya Terhadap Bangunan Masjid Jami' Tan Kok Liong Di BogorDocument196 pagesAnalisis Semiotik Budaya Terhadap Bangunan Masjid Jami' Tan Kok Liong Di BogorAudry RikumahuPas encore d'évaluation

- Kajian Konservasi Bangunan Cagar Budaya Pada Koridor Jl. Kepodang Kota SemarangDocument8 pagesKajian Konservasi Bangunan Cagar Budaya Pada Koridor Jl. Kepodang Kota Semarangawan conanPas encore d'évaluation

- Kuliah - Pengantar Bangunan Tinggi (SPA3-SK5)Document68 pagesKuliah - Pengantar Bangunan Tinggi (SPA3-SK5)Seungcheol ChoiPas encore d'évaluation

- The History and Structure of the Millennium Dome and O2 ArenaDocument12 pagesThe History and Structure of the Millennium Dome and O2 ArenaShanmuga PriyaPas encore d'évaluation

- 002 - Presentation On Folded Plate StructuresDocument40 pages002 - Presentation On Folded Plate StructuresSamreen KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Building Science 2Document43 pagesBuilding Science 2thisisthemanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gate of Creation-Tadao AndoDocument2 pagesThe Gate of Creation-Tadao AndoLakshiminaraayanan SudhakarPas encore d'évaluation

- Fuzhou Wusibei Thaihot PlazaDocument6 pagesFuzhou Wusibei Thaihot PlazaFirmanHidayatPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Architecture (ARC 2234) Project 1: Case StudyDocument29 pagesAsian Architecture (ARC 2234) Project 1: Case StudyTsaiWanChingPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Lee Rubber AssignmentDocument33 pagesFinal Lee Rubber Assignmentsusie_gal8675% (4)

- Presentasi Pengantar Arsitektur Zaha HadidDocument21 pagesPresentasi Pengantar Arsitektur Zaha HadidAbdullah Indra PratamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Judul Gambar Denah Aquatic Center Lantai 1: Ruang MakanDocument1 pageJudul Gambar Denah Aquatic Center Lantai 1: Ruang Makanrahman olengPas encore d'évaluation

- Suvarnabhumi AirportDocument16 pagesSuvarnabhumi AirportVannyPas encore d'évaluation

- Country: Bangladesh Building: Jatiyo Sangsad Bhaban Architect:Louis I KahnDocument18 pagesCountry: Bangladesh Building: Jatiyo Sangsad Bhaban Architect:Louis I KahnKavya JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Lou RuvoDocument22 pagesLou RuvoMaria HakpaPas encore d'évaluation

- Etika ProfesiDocument12 pagesEtika ProfesidillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Setia City Mall - Malaysia's 1st Green Mall. by IEN ConsultantsDocument2 pagesSetia City Mall - Malaysia's 1st Green Mall. by IEN ConsultantsNur SyahiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport, ChinaDocument8 pagesShenzhen Bao'an International Airport, ChinaSonit NemaPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical & Cultural Urban Space UploadDocument15 pagesHistorical & Cultural Urban Space Uploadirwan yuliantoPas encore d'évaluation

- InTech-Designing Urban SquaresDocument18 pagesInTech-Designing Urban SquaresValery OchoaPas encore d'évaluation

- 3D Spatial Development of Historic Urban Landscape To Promote A Historical Spatial Data SystemDocument13 pages3D Spatial Development of Historic Urban Landscape To Promote A Historical Spatial Data SystemIEREKPRESSPas encore d'évaluation

- Green Building Carbon Rating Tool ApplicationDocument4 pagesGreen Building Carbon Rating Tool ApplicationOliver JJ TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Tartini Violin Sonata Op 1 No 10 ViolinDocument6 pagesTartini Violin Sonata Op 1 No 10 ViolinOliver JJ TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Drawing1 ModelDocument1 pageDrawing1 ModelOliver JJ TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pachelbel Canon Violin3Document2 pagesPachelbel Canon Violin3Oliver JJ TanPas encore d'évaluation

- GNED 500 Social AnalysisDocument2 pagesGNED 500 Social AnalysisEshita SinhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ghana Constitution 1996Document155 pagesGhana Constitution 1996manyin1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Metabical Positioning and CommunicationDocument15 pagesMetabical Positioning and CommunicationJSheikh100% (2)

- What is a Literature ReviewDocument21 pagesWhat is a Literature ReviewJSPPas encore d'évaluation

- Operations Management Success FactorsDocument147 pagesOperations Management Success Factorsabishakekoul100% (1)

- Aviation Case StudyDocument6 pagesAviation Case Studynabil sayedPas encore d'évaluation

- Giles. Saint Bede, The Complete Works of Venerable Bede. 1843. Vol. 8.Document471 pagesGiles. Saint Bede, The Complete Works of Venerable Bede. 1843. Vol. 8.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Validated UHPLC-MS - MS Method For Quantification of Doxycycline in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm PatientsDocument14 pagesValidated UHPLC-MS - MS Method For Quantification of Doxycycline in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm PatientsAkhmad ArdiansyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrating GrammarDocument8 pagesIntegrating GrammarMaría Perez CastañoPas encore d'évaluation

- Compiler Design Lab ManualDocument24 pagesCompiler Design Lab ManualAbhi Kamate29% (7)

- Elderly Suicide FactsDocument2 pagesElderly Suicide FactsThe News-HeraldPas encore d'évaluation

- All Projects Should Be Typed On A4 SheetsDocument3 pagesAll Projects Should Be Typed On A4 SheetsNikita AgrawalPas encore d'évaluation

- Week C - Fact Vs OpinionDocument7 pagesWeek C - Fact Vs OpinionCharline A. Radislao100% (1)

- Q-Win S Se QuickguideDocument22 pagesQ-Win S Se QuickguideAndres DennisPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study of Outdoor Interactional Spaces in High-Rise HousingDocument13 pagesA Study of Outdoor Interactional Spaces in High-Rise HousingRekha TanpurePas encore d'évaluation

- Budokon - Mma.program 2012 13Document10 pagesBudokon - Mma.program 2012 13Emilio DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- Statistics Machine Learning Python DraftDocument319 pagesStatistics Machine Learning Python DraftnagPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Outline IST110Document4 pagesCourse Outline IST110zaotrPas encore d'évaluation

- ProbabilityDocument2 pagesProbabilityMickey WongPas encore d'évaluation

- Jason A Brown: 1374 Cabin Creek Drive, Nicholson, GA 30565Document3 pagesJason A Brown: 1374 Cabin Creek Drive, Nicholson, GA 30565Jason BrownPas encore d'évaluation

- Rak Single DentureDocument48 pagesRak Single Denturerakes0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cps InfographicDocument1 pageCps Infographicapi-665846419Pas encore d'évaluation

- Normal Distribution: X e X FDocument30 pagesNormal Distribution: X e X FNilesh DhakePas encore d'évaluation

- Development of Branchial ArchesDocument4 pagesDevelopment of Branchial ArchesFidz LiankoPas encore d'évaluation

- Graphic Design Review Paper on Pop Art MovementDocument16 pagesGraphic Design Review Paper on Pop Art MovementFathan25 Tanzilal AziziPas encore d'évaluation

- Grecian Urn PaperDocument2 pagesGrecian Urn PaperrhesajanubasPas encore d'évaluation

- Digoxin FABDocument6 pagesDigoxin FABqwer22Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coek - Info Anesthesia and Analgesia in ReptilesDocument20 pagesCoek - Info Anesthesia and Analgesia in ReptilesVanessa AskjPas encore d'évaluation

- Importance of SimilesDocument10 pagesImportance of Similesnabeelajaved0% (1)

- Reviews: Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery: A Shift in Eligibility and Success CriteriaDocument13 pagesReviews: Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery: A Shift in Eligibility and Success CriteriaJulia SCPas encore d'évaluation