Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Mneumonics PsychDx

Transféré par

Suraj MukatiraTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Mneumonics PsychDx

Transféré par

Suraj MukatiraDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Current Psychiatry

Vol. 7, No. 10 27

Mnemonics in a mnutshell:

32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis

Clever, irreverent, or amusing,

a mnemonic you remember

is a lifelong learning tool

Jason P. Caplan, MD

Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry

Creighton University School of Medicine

Omaha, NE

Chief of psychiatry

St. Josephs Hospital and Medical Center

Phoenix, AZ

Theodore A. Stern, MD

Professor of psychiatry

Harvard Medical School

Chief, psychiatric consultation service

Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, MA

F

rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS,

mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall

important lists (such as criteria for depression,

screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening

causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics effcacy

rests on the principle that grouped information is easi-

er to remember than individual points of data.

Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting

diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and

research, on board examinations, and for insurance

reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di-

agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and

teaching.

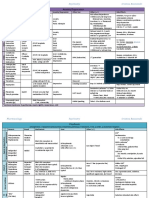

In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli-

nicians diagnose:

affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)

1,2

anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)

3-6

medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29)

7,8

personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)

9-11

addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)

12,13

causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).

14

We also discuss how mnemonics improve ones

memory, based on the principles of learning theory.

How mnemonics work

A mnemonicfrom the Greek word mnemonikos

(of memory)links new data with previously learned

information. Mnemonics assist in learning by reducing

the amount of information (cognitive load) that needs

J

U

P

I

T

E

R

I

M

A

G

E

S

27_CPSY1008 27 9/12/08 3:20:58 PM

C

o

p

y

r

i

g

h

t

D

o

w

d

e

n

H

e

a

l

t

h

M

e

d

i

a

F

o

r

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

u

s

e

o

n

l

y

For mass reproduction, content licensing and permissions contact Dowden Health Media.

Current Psychiatry

October 2008 28

Mnemonics

BOX 1. MNEMONICS FOR DIAGNOSING AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Depression

SIG: E CAPS*

Suicidal thoughts

Interests decreased

Guilt

Energy decreased

Concentration decreased

Appetite disturbance

(increased or decreased)

Psychomotor changes

(agitation or retardation)

Sleep disturbance

(increased or decreased)

* Created by Carey Gross, MD

Dysthymia

HES 2 SAD

2

Hopelessness

Energy loss or fatigue

Self-esteem is low

2 years minimum of depressed

mood most of the day, for more

days than not

Sleep is increased or decreased

Appetite is increased or decreased

Decision-making or concentration

is impaired

Mania

DIG FAST

Distractibility

Indiscretion

Grandiosity

Flight of ideas

Activity increase

Sleep defcit

Talkativeness

Depression

C GASP DIE

1

Concentration decreased

Guilt

Appetite

Sleep disturbance

Psychomotor agitation or retardation

Death or suicide (thoughts or acts of)

Interests decreased

Energy decreased

Hypomania

TAD HIGH

Talkative

Attention defcit

Decreased need for sleep

High self-esteem/grandiosity

Ideas that race

Goal-directed activity increased

High-risk activity

Mania

DeTeR the HIGH*

Distractibility

Talkativeness

Reckless behavior

Hyposomnia

Ideas that race

Grandiosity

Hypersexuality

* Created by Carey Gross, MD

to be stored for long-term processing and

retrieval.

15

Memory, defned as the persistence of

learning in a state that can be revealed at a

later time,

16

can be divided into 2 types:

declarative (a conscious recollection of

facts, such as remembering a relatives

birthday)

procedural (skills-based learning, such

as riding a bicycle).

Declarative memory has a conscious

component and may be mediated by the

medial temporal lobe and cortical associa-

tion structures. Procedural memory has less

of a conscious component; it may involve

the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and a variety

of cortical sensory-perceptive regions.

17

Declarative memory can be subdivided into

working memory and long-term memory.

With working memory, new items of infor-

mation are held briefy so that encoding

and eventual storage can take place.

Working memory guides decision-

making and future planning and is intri-

cately related to attention.

18-21

Functional

MRI and positron emission tomography

as well as neurocognitive testing have

shown that working memory tasks ac-

tivate the prefrontal cortex and brain

regions specifc to language and visuo-

spatial memory.

The hippocampus is thought to rapidly

absorb new information, and this data is

consolidated and permanently stored via

the prefrontal cortex.

22-26

Given the hippo-

campus limited storage capacity, new infor-

mation (such as what you ate for breakfast

3 weeks ago) will disappear if it is not re-

peated regularly.

17

28_CPSY1008 28 9/12/08 3:21:03 PM

Current Psychiatry

Vol. 7, No. 10 29

Clinical Point

TK

Clinical Point

TK

BOX 2. MNEMONICS FOR DIAGNOSING ANXIETY DISORDERS

Long-term memory, on the other hand, is

encoded knowledge that is linked to facts

learned in the past; it is consolidated in

the brain and can be readily retrieved.

Neuroimaging studies have demonstrat-

ed opposing patterns of activation in the

hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, de-

pending on whether the memory being

recalled is:

new (high hippocampal activity, low

prefrontal cortex activity)

old (low hippocampal activity, high

prefrontal cortex activity).

27

Mnemonics are thought to affect working

memory by reducing the introduced cog-

nitive load and increasing the effciency of

memory acquisition and encoding. They

reduce cognitive load by grouping ob-

jects into a single verbal or visual cue that

can be introduced into working memory.

Learning is optimized when the load on

BOX 3. MNEMONICS FOR DIAGNOSING MEDICATION ADVERSE EFFECTS

Antidepressant discontinuation

syndrome

FINISH

7

Flu-like symptoms

Insomnia

Nausea

Imbalance

Sensory disturbances

Hyperarousal (anxiety/agitation)

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

FEVER

8

Fever

Encephalopathy

Vital sign instability

Elevated WBC/CPK

Rigidity

WBC: white blood cell count

CPK: creatine phosphokinase

Serotonin syndrome

HARMED

Hyperthermia

Autonomic instability

Rigidity

Myoclonus

Encephalopathy

Diaphoresis

Clinical Point

TK

Generalized anxiety disorder

Worry WARTS

3

Wound up

Worn-out

Absentminded

Restless

Touchy

Sleepless

Posttraumatic stress disorder

TRAUMA

5

Traumatic event

Re-experience

Avoidance

Unable to function

Month or more of symptoms

Arousal increased

Anxiety disorder due to a

general medical condition

Physical Diseases That Have

Commonly Appeared Anxious:

Pheochromocytoma

Diabetes mellitus

Temporal lobe epilepsy

Hyperthyroidism

Carcinoid

Alcohol withdrawal

Arrhythmias

Generalized anxiety disorder

WATCHERS

4

Worry

Anxiety

Tension in muscles

Concentration diffculty

Hyperarousal (or irritability)

Energy loss

Restlessness

Sleep disturbance

Posttraumatic stress disorder

DREAMS

6

Disinterest in usual activities

Re-experience

Event preceding symptoms

Avoidance

M onth or more of symptoms

Sympathetic arousal

29_CPSY1008 29 9/16/08 12:06:16 PM

Current Psychiatry

October 2008 30

Mnemonics

BOX 4. MNEMONICS FOR DIAGNOSING PERSONALITY DISORDERS

working memory is minimized, enabling

long-term memory to be facilitated.

28

Mnemonics may use rhyme, music, or

visual cues to enhance memory. Most mne-

monics used in medical practice and edu-

cation are word-based, including:

Acronymswords, each letter of which

stands for a particular piece of information

to be recalled (such as RICE for treatment

of a sprained joint: rest, ice, compression,

elevation).

Acrosticssentences with the frst let-

ter of each word prompting the desired

recollection (such as To Zanzibar by mo-

tor car for the branches of the facial nerve:

temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular,

cervical).

Alphabetical sequences (such as ABCDE

of trauma assessment: airway, breathing,

circulation, disability, exposure).

29

An appropriate teaching tool?

Dozens of mnemonics addressing psychi-

atric diagnosis and treatment have been

published, but relatively few are widely

used. Psychiatric educators may resist

teaching with mnemonics, believing they

might erode a humanistic approach to pa-

tients by reducing psychopathology to a

laundry list of symptoms and the art of

psychiatric diagnosis to a check-box en-

deavor. Mnemonics that use humor may

be rejected as irreverent or unprofession-

al.

30

Publishing a novel mnemonic may be

viewed with disdain by some as an easy

way of padding a curriculum vitae.

Entire Web sites exist to share mnemon-

ics for medical education (see Related

Resources, page 33). Thus it is likely that

trainees are using them with or without

their teachers supervision. Psychiatric ed-

Paranoid personality disorder

SUSPECT

9

Spousal infdelity suspected

Unforgiving (bears grudges)

Suspicious

Perceives attacks (and reacts

quickly)

Enemy or friend? (suspects

associates and friends)

Confding in others is feared

Threats perceived in benign

events

Schizotypal personality disorder

ME PECULIAR

9

Magical thinking

Experiences unusual perceptions

Paranoid ideation

Eccentric behavior or appearance

Constricted or inappropriate affect

Unusual thinking or speech

Lacks close friends

Ideas of reference

Anxiety in social situations

Rule out psychotic or pervasive

developmental disorders

Borderline personality disorder

IMPULSIVE

10

Impulsive

Moodiness

Paranoia or dissociation under stress

Unstable self-image

Labile intense relationships

Suicidal gestures

Inappropriate anger

Vulnerability to abandonment

Emptiness (feelings of)

Schizoid personality disorder

DISTANT

9

Detached or fattened affect

Indifferent to criticism or praise

Sexual experiences of little interest

Tasks done solitarily

Absence of close friends

Neither desires nor enjoys

close relationships

Takes pleasure in few activities

Antisocial personality disorder

CORRUPT

9

Cannot conform to law

Obligations ignored

Reckless disregard for safety

Remorseless

Underhanded (deceitful)

Planning insuffcient (impulsive)

Temper (irritable and aggressive)

Borderline personality disorder

DESPAIRER*

Disturbance of identity

Emotionally labile

Suicidal behavior

Paranoia or dissociation

Abandonment (fear of)

Impulsive

Relationships unstable

Emptiness (feelings of)

Rage (inappropriate)

* Created by Jason P. Caplan, MD

30_CPSY1008 30 9/12/08 3:21:12 PM

Current Psychiatry

Vol. 7, No. 10 31

ucators need to be aware of the mnemonics

their trainees are using and to:

screen these tools for factual errors

(such as incomplete diagnostic criteria)

remind trainees that although mne-

monics are useful, psychiatrists should ap-

proach patients as individuals without the

prejudice of a potentially pejorative label.

Our methodology

In preparing this article, we gathered

numerous mnemonics (some published

and some novel) designed to capture the

learners attention and impart informa-

tion pertinent to psychiatric diagnosis and

treatment. Whenever possible, we credited

each mnemonic to its creator, butgiven

the diffculty in confrming authorship of

(what in many cases has become) oral his-

toryweve listed some mnemonics with-

out citation.

Our list is far from complete because we

likely are unaware of many mnemonics,

and we have excluded some that seemed

obscure, unwieldy, or redundant. We have

not excluded mnemonics that some may

view as pejorative but merely report their

existence. Including them does not mean

that we endorse them.

This article lists 32 mnemonics related

to psychiatric diagnosis. Thus, it seems

odd that an informal survey of >60 resi-

dents at the Massachusetts General Hos-

pital (MGH)/McLean Residency Training

Program in Psychiatry revealed that most

were aware of only 2 or 3 psychiatric mne-

monics, typically:

SIG: E CAPS (a tool to recall the criteria

for depression)

Histrionic personality disorder

PRAISE ME

9

Provocative or seductive behavior

Relationships considered more

intimate than they are

Attention (need to be the center of)

Infuenced easily

Style of speech (impressionistic,

lacking detail)

Emotions (rapidly shifting, shallow)

Make up (physical appearance

used to draw attention to self)

Emotions exaggerated

Narcissistic personality disorder

GRANDIOSE

11

Grandiose

Requires attention

Arrogant

Need to be special

Dreams of success and power

Interpersonally exploitative

Others (unable to recognize

feelings/needs of)

Sense of entitlement

Envious

Dependent personality disorder

RELIANCE

9

Reassurance required

Expressing disagreement diffcult

Life responsibilities assumed by others

Initiating projects diffcult

Alone (feels helpless and

uncomfortable when alone)

Nurturance (goes to excessive

lengths to obtain)

Companionship sought urgently

when a relationship ends

Exaggerated fears of being left

to care for self

Histrionic personality disorder

ACTRESSS*

Appearance focused

Center of attention

Theatrical

Relationships (believed to be

more intimate than they are)

Easily infuenced

Seductive behavior

Shallow emotions

Speech (impressionistic and vague)

* Created by Jason P. Caplan, MD

Avoidant personality disorder

CRINGES

9

Criticism or rejection preoccupies

thoughts in social situations

Restraint in relationships due to

fear of shame

Inhibited in new relationships

Needs to be sure of being liked

before engaging socially

Gets around occupational activities

with need for interpersonal contact

Embarrassment prevents new

activity or taking risks

Self viewed as unappealing or inferior

Obsessive-compulsive personality

disorder

SCRIMPER*

Stubborn

Cannot discard worthless objects

Rule obsessed

Infexible

Miserly

Perfectionistic

Excludes leisure due to devotion

to work

Reluctant to delegate to others

* Created by Jason P. Caplan, MD

continued

31_CPSY1008 31 9/12/08 3:21:17 PM

Current Psychiatry

October 2008 32

Mnemonics

BOX 6. MNEMONICS FOR DIAGNOSING DELIRIUM

BOX 5. MNEMONICS FOR DIAGNOSING ADDICTION DISORDERS

DIG FAST (a list of criteria for diagnos-

ing mania)

WWHHHHIMPS (a tool for recalling

life-threatening causes of delirium).

Although this unscientifc survey may

be biased because faculty or trainees at

MGH created the above 3 mnemonics,

it nonetheless begs the question of what

qualities make a mnemonic memorable.

Learning theory provides several clues.

George Millers classic 1956 paper, The

magical number seven, plus or minus two:

some limits on our capacity for processing

information, discussed the fnding that 7

seems to be the upper limit of individual

pieces of data that can be easily remem-

bered.

31

Research also has shown that re-

cruiting the limbic system (potentially

through the use of humor) aids in the recall

of otherwise dry, cortical information.

32,33

Intuitively, it would seem that nonre-

peating letters would facilitate the recall of

the linked data, allowing each letter to pro-

vide a distinct cue, without any clouding

by redundancy. Of the 3 most popular psy-

chiatric mnemonics, however, only DIG

FAST fts the learning theory. It contains 7

letters, repeats no letters, and has the lim-

bic cue of allowing the learner to imagine a

person with mania digging furiously.

SIG: E CAPS falls within the range of

7 plus or minus 2, includes a limbic cue

Causes

I WATCH DEATH

Infection

Withdrawal

Acute metabolic

Trauma

CNS pathology

Hypoxia

Defciencies

Endocrinopathies

Acute vascular

Toxins or drugs

Heavy metals

Life-threatening causes

WWHHHHIMPS*

Wernickes encephalopathy

Withdrawal

Hypertensive crisis

Hypoperfusion/hypoxia of the brain

Hypoglycemia

Hyper/hypothermia

Intracranial process/infection

Metabolic/meningitis

Poisons

Status epilepticus

* Created by Gary W. Small, MD

Deliriogenic medications

ACUTE CHANGE IN MS

14

Antibiotics

Cardiac drugs

Urinary incontinence drugs

Theophylline

Ethanol

Corticosteroids

H2 blockers

Antiparkinsonian drugs

Narcotics

Geriatric psychiatric drugs

ENT drugs

Insomnia drugs

NSAIDs

Muscle relaxants

Seizure medicines

Substance dependence

ADDICTeD

12

Activities are given up or reduced

Dependence, physical: tolerance

Dependence, physical: withdrawal

Intrapersonal (Internal)

consequences, physical or

psychological

Cant cut down or control use

Time-consuming

Duration or amount of use is greater

than intended

Substance abuse

WILD

12

Work, school, or home role

obligation failures

Interpersonal or social consequences

Legal problems

Dangerous use

Alcohol abuse

CAGE

13

Have you ever felt you should

CUT DOWN your drinking?

Have people ANNOYED you

by criticizing your drinking?

Have you ever felt bad or

GUILTY about your drinking?

Have you ever had a drink frst

thing in the morning to steady

your nerves or get rid of a

hangover (EYE-OPENER)?

32_CPSY1008 32 9/12/08 3:21:21 PM

Current Psychiatry

Vol. 7, No. 10 33

(although often forgotten, it refers to the

prescription of energy capsules for depres-

sion), but repeats the letter S.

WWHHHHIMPS, with 10 letters, ex-

ceeds the recommended range, repeats the

W (appearing twice) and the H (appearing

4 times), and provides no clear limbic cue.

It may be that recruiting the limbic sys-

tem provides the greatest likelihood of

recall. Recruiting this system may add in-

creased valence to a particular mnemonic

for a specifc individual, but this same

limbic valence may limit its usefulness in

a professional context.

References

1. Abraham PF, Shirley ER. New mnemonic for depressive

symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(2):329-30.

2. Christman DS. HES 2 SAD detects dysthymic disorder.

Current Psychiatry 2008;7(3):120.

3. Coupland NJ. Worry WARTS have generalized anxiety

disorder. Can J Psychiatry 2002;47(2):197.

4. Berber MJ. WATCHERS: recognizing generalized anxiety

disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(6):447.

5. Khouzam HR. A simple mnemonic for the diagnostic criteria

for post-traumatic stress disorder. West J Med 2001;174(6):424.

6. Short DD, Workman EA, Morse JH, Turner RL. Mnemonics

for eight DSM-III-R disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry

1992;43(6):642-4.

7. Berber MJ. FINISH: remembering the discontinuation

syndrome. Flu-like symptoms, Insomnia, Nausea, Imbalance,

Sensory disturbances, and Hyperarousal (anxiety/agitation).

J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(5):255.

8. Christensen RC. Identify neuroleptic malignant syndrome

with FEVER. Current Psychiatry 2005;4(7):102.

9. Pinkofsky HB. Mnemonics for DSM-IV personality disorders.

Psychiatr Serv 1997;48(9):1197-8.

10. Senger HL. Borderline mnemonic. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154(9):

1321.

11. Kim SI, Swanson TA, Caplan JP, eds. Underground clinical

vignettes step 2: psychiatry. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins; 2007:130.

12. Bogenschutz MP, Quinn DK. Acronyms for substance use

disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(6):474-5.

13. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire.

JAMA 1984;252(14):1905-7.

14. Flaherty JH. Psychotherapeutic agents in older adults.

Commonly prescribed and over-the-counter remedies: causes

of confusion. Clin Geriatr Med 1998;14:101-27.

15. Sweller J. Cognitive load theory, learning diffculty, and

instructional design. Learn Instr 1994;4:295-312.

16. Squire LR. Memory and brain. New York, NY: Oxford University

Press; 1987.

17. DeLuca J, Lengenfelder J, Eslinger P. Memory and learning.

In: Rizzo M, Eslinger P, eds. Principles and practice of behavioral

neurology and neuropsychology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders;

2004:251.

18. Dash PK, Moore AN, Kobori N, et al. Molecular activity

underlying working memory. Learn Mem 2007;14:554-63.

19. Awh E, Vogel EK, Oh SH. Interactions between attention and

working memory. Neuroscience 2006;139:201-8.

20. Knudson EI. Fundamental components of attention. Ann Rev

Neurosci 2007;30:57-78.

21. Postle BR. Working memory as an emergent property of the

mind and brain. Neuroscience 2006;139:23-36.

22. Fletcher PC, Henson RN. Frontal lobes and human memory:

Insights from functional neuroimaging. Brain 2001;124:849-

81.

23. Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal

cortex function. Ann Rev Neurosci 2001;24:167-202.

24. Schumacher EH, Lauber E, Awh E, et al. PET evidence for a

modal verbal working memory system. Neuroimage 1996;3:79-

88.

25. Smith EE, Jonides J, Koeppe RA. Dissociating verbal and

spatial working memory using PET. Cereb Cortex 1996;6:11-20.

26. Wager TD, Smith EE. Neuroimaging studies of working

memory: a meta-analysis. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2003;3(4):

255-74.

27. Frankland PW, Bontempi B. The organization of recent and

remote memories. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005;6:119-30.

28. Sweller J. Cognitive load during problem solving: effects on

learning. Cogn Sci 1988;12(1):257-85.

29. Beitz JM. Unleashing the power of memory: the mighty

mnemonic. Nurse Educ 1997;22(2):25-9.

30. Larson EW. Criticism of mnemonic device. Am J Psychiatry

1990;147(7):963-4.

31. Miller GA. The magical number seven, plus or minus two:

some limits on our capacity for processing information.

Psychol Rev 1956;63:81-97.

32. Schmidt SR. Effects of humor on sentence memory. J Exp

Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 1994;20(4):953-67.

33. Lippman LG, Dunn ML. Contextual connections within

puns: effects on perceived humor and memory. J Gen Psychol

2000;127(2):185-97.

Related Resources

Free searchable database of medical mnemonics. www.

medicalmnemonics.com.

Robinson DJ. Mnemonics and more for psychiatry. Port

Huron, MI: Rapid Psychler Press, 2001.

Recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice, on board examinations,

and for insurance reimbursement. Mnemonics are well-suited to learning and

recalling lists of signs and symptoms required for accurate psychiatric diagnosis.

Bottom Line

Clinical Point

We included some

mnemonics that

may be viewed as

pejorative, but that

does not mean

we endorse them

33_CPSY1008 33 9/12/08 3:21:26 PM

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Drugs - Opium For The Masses PDFDocument63 pagesDrugs - Opium For The Masses PDFconfused59775% (4)

- Speech On Drug Abuse 1Document2 pagesSpeech On Drug Abuse 1Lorentz Rarugal Asis86% (7)

- FungiDocument24 pagesFungiNatosha Mendoza100% (1)

- Holmes Ra He Stress TestDocument2 pagesHolmes Ra He Stress TestHendri PrasetyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychiatry Student Guide: MEDD 421 Clinical Skills 2019-2020Document25 pagesPsychiatry Student Guide: MEDD 421 Clinical Skills 2019-2020Rubie Ann TillorPas encore d'évaluation

- First Aid PsychiatryDocument156 pagesFirst Aid PsychiatryMae Matira AbeladorPas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Mimics 2016Document24 pagesMedical Mimics 2016Susan Redmond-VaughtPas encore d'évaluation

- Neoplasms of The LungDocument17 pagesNeoplasms of The Lungnathan asfahaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mnemonics in A Mnutshell - 32 Aids To Psychiatric Diagnosis - Current PsychiatryDocument8 pagesMnemonics in A Mnutshell - 32 Aids To Psychiatric Diagnosis - Current Psychiatrygfish6Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pharmacology Workbook Class of 20 20: (Revised: March, 2018)Document22 pagesPharmacology Workbook Class of 20 20: (Revised: March, 2018)Navdeep RandhawaPas encore d'évaluation

- Translate Kaplan Sadock Sinopsis Psikiatri Komprehensif Halaman 721 730 PDF FreeDocument76 pagesTranslate Kaplan Sadock Sinopsis Psikiatri Komprehensif Halaman 721 730 PDF FreeHadi GunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Statement - FinalDocument2 pagesPersonal Statement - Finalapi-383932502Pas encore d'évaluation

- INTRODUCTION TO NEUROPHARMACOLOGYyyDocument27 pagesINTRODUCTION TO NEUROPHARMACOLOGYyyEbad RazviPas encore d'évaluation

- DIT Answers Combined PDFDocument17 pagesDIT Answers Combined PDFJohnHauftmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pharmacology (1) - 104-122Document19 pagesPharmacology (1) - 104-122Dental LecturesMMQPas encore d'évaluation

- Mirtazapine PDF PDFDocument23 pagesMirtazapine PDF PDFBoneGrisslePas encore d'évaluation

- Psychiatrypoisoning E.ODocument24 pagesPsychiatrypoisoning E.OZeenat JunaidPas encore d'évaluation

- UW Notes - 13 - PsychiatryDocument21 pagesUW Notes - 13 - PsychiatryDor BenayounPas encore d'évaluation

- Clozapine Care GuideDocument16 pagesClozapine Care GuideERWIN SUMARDIPas encore d'évaluation

- NeurologyDocument4 pagesNeurologyClaudioAhumadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy Lecture 19,20,21: 1 Hour 04,06,08-11-2013Document64 pagesAnatomy Lecture 19,20,21: 1 Hour 04,06,08-11-2013Batot EvaPas encore d'évaluation

- 3.5 The Approach To Trauma - 2 Hour Lecture-TzDocument74 pages3.5 The Approach To Trauma - 2 Hour Lecture-TzOjambo FlaviaPas encore d'évaluation

- Psych Notes Case FilesDocument5 pagesPsych Notes Case FilesMitz JunePas encore d'évaluation

- Cardiovascular Complications of Antipsychotic MedicationsDocument3 pagesCardiovascular Complications of Antipsychotic MedicationsAakash ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- PsychiatryDocument92 pagesPsychiatrykimPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Introduction To PsychiatryDocument29 pages01 Introduction To PsychiatryPatricia Denise OrquiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Psychiatric Nursing: Mercedes A Perez-Millan MSN, ARNPDocument33 pagesIntroduction To Psychiatric Nursing: Mercedes A Perez-Millan MSN, ARNPSachiko Yosores100% (1)

- Ect (Part I) : Mira Hezrina Binti Marzaki Group 5Document13 pagesEct (Part I) : Mira Hezrina Binti Marzaki Group 5f4rog4iePas encore d'évaluation

- Article - Medical ErrorsDocument4 pagesArticle - Medical ErrorsDavid S. ChouPas encore d'évaluation

- The Audio PANCE and PANRE Episode 9Document4 pagesThe Audio PANCE and PANRE Episode 9The Physician Assistant Life100% (1)

- 2012-13 Psychiatry Board ReviewDocument79 pages2012-13 Psychiatry Board Reviewlizzy596100% (1)

- Pharmacology - (5) Psychotic DrugsDocument8 pagesPharmacology - (5) Psychotic DrugsSamantha DiegoPas encore d'évaluation

- MedbooksDocument1 pageMedbooksLavinia BădiciPas encore d'évaluation

- Malingering NbiDocument5 pagesMalingering NbiPridina SyadirahPas encore d'évaluation

- Medication Assisted Treatment of Opioid Use.2Document13 pagesMedication Assisted Treatment of Opioid Use.2tatanmenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Neuro Notes UWDocument91 pagesNeuro Notes UWM.DalaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Terms in The Field of PsychiatryDocument18 pagesTerms in The Field of PsychiatryOchie YecyecanPas encore d'évaluation

- Joshua Dodot Case StudyDocument2 pagesJoshua Dodot Case StudyJoshua Ringor100% (1)

- Introduction To History Taking Aims:: Summary of Procedure and NotesDocument6 pagesIntroduction To History Taking Aims:: Summary of Procedure and Notesmj.vinoth@gmail.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychiatry Notes - Depressive DisorderDocument2 pagesPsychiatry Notes - Depressive DisorderLiSenPas encore d'évaluation

- Anxiety Disorder MCQsDocument6 pagesAnxiety Disorder MCQsIhtisham Ul Haq 1525-FSS/BSPSY/F20Pas encore d'évaluation

- Why Psychiatry? Some Thoughts For Medical Students.Document3 pagesWhy Psychiatry? Some Thoughts For Medical Students.Davin TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Geriatric Giants - DR SeymourDocument108 pagesGeriatric Giants - DR SeymourSharon Mallia100% (1)

- PSYCH - PsychosomaticdelasalleDocument58 pagesPSYCH - Psychosomaticdelasalleapi-3856051100% (1)

- Tranylcypromine in Mind Part II - Review of Clinical PH - 2017 - European Neuro PDFDocument18 pagesTranylcypromine in Mind Part II - Review of Clinical PH - 2017 - European Neuro PDFdanilomarandolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Neuroleptics & AnxiolyticsDocument65 pagesNeuroleptics & AnxiolyticsAntonPurpurovPas encore d'évaluation

- Dementia: Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument53 pagesDementia: Diagnosis and Treatmentakashdeep050% (1)

- Neurocognitive Disorders Delirium: For Major Neurocognitive DisorderDocument2 pagesNeurocognitive Disorders Delirium: For Major Neurocognitive DisordermjgirasolPas encore d'évaluation

- PsychopharmacologyDocument49 pagesPsychopharmacologysazaki224Pas encore d'évaluation

- Resident Handbook Rev 8.22.2014 - Redacted PDFDocument244 pagesResident Handbook Rev 8.22.2014 - Redacted PDFDr-Shoaib ZafarPas encore d'évaluation

- June 2021 MCQ Psychiatry at DAMSDocument61 pagesJune 2021 MCQ Psychiatry at DAMSAli HusseinPas encore d'évaluation

- DR - Usama.mahmoud Psychiatry - Notes MSDocument64 pagesDR - Usama.mahmoud Psychiatry - Notes MSMariam A. KarimPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods Used in EpidemologyDocument53 pagesMethods Used in EpidemologySameera banuPas encore d'évaluation

- Current Clinical Strategies: Handbook of Psychiatric DrugsDocument72 pagesCurrent Clinical Strategies: Handbook of Psychiatric Drugsmike116Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anxiety/Depression: S AlprazolamDocument2 pagesAnxiety/Depression: S AlprazolamleesaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consulatation Liaison Psychiatry English Lecture 2012 10Document58 pagesConsulatation Liaison Psychiatry English Lecture 2012 10Vean Doank100% (1)

- Psychiatry Made EasyDocument14 pagesPsychiatry Made EasyD. W. S JayarathnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Second-Generation Antipsychotics and Pregnancy ComplicationsDocument9 pagesSecond-Generation Antipsychotics and Pregnancy ComplicationsDian Oktaria SafitriPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychiatry ExamDocument4 pagesPsychiatry Examapi-3703352Pas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated Bibliography FinalDocument9 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Finalapi-546389655Pas encore d'évaluation

- Year 6 Clerkship - Welcome & Curriculum Class 2020 (Revised 25.04.2019)Document190 pagesYear 6 Clerkship - Welcome & Curriculum Class 2020 (Revised 25.04.2019)Ali SemajPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychiatric Case Clerking for Medical StudentsD'EverandPsychiatric Case Clerking for Medical StudentsPas encore d'évaluation

- Mood Disorders V 2 Hand OutDocument27 pagesMood Disorders V 2 Hand OutSuraj MukatiraPas encore d'évaluation

- ADHD2015 BWDocument15 pagesADHD2015 BWSuraj MukatiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Peds Lecture 3Document19 pagesPeds Lecture 3Suraj Mukatira100% (1)

- Chapter - 058 - Stroke Elseivier Powerpoint For My Class LectureDocument52 pagesChapter - 058 - Stroke Elseivier Powerpoint For My Class LectureSuraj Mukatira100% (2)

- n3180 - Ch. 10 Pain Ppt-StudentDocument43 pagesn3180 - Ch. 10 Pain Ppt-StudentSuraj MukatiraPas encore d'évaluation

- #4 Postpartum.2013SCpptx (1) .PPTX - 0Document35 pages#4 Postpartum.2013SCpptx (1) .PPTX - 0Suraj MukatiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Health AssesmentDocument3 pagesHealth AssesmentSuraj MukatiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Hesi HintsDocument4 pagesHesi HintsSuraj Mukatira100% (1)

- High Risk Newborn: 2013studentDocument64 pagesHigh Risk Newborn: 2013studentSuraj MukatiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Autoimmune Disorder Case StudyDocument38 pagesAutoimmune Disorder Case StudySuraj MukatiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 6Document10 pagesChapter 6Suraj MukatiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Street SlangDocument38 pagesStreet SlangChae No100% (1)

- Research Roadmap 3.1: The Reflective StatementDocument2 pagesResearch Roadmap 3.1: The Reflective Statementmtlol17Pas encore d'évaluation

- AmphetamineDocument15 pagesAmphetamineIoanadmic83% (6)

- The History of DrugsDocument15 pagesThe History of DrugsMark Maylben O. DezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Advertisement ONE (Educating People On How To Accept Them)Document11 pagesAdvertisement ONE (Educating People On How To Accept Them)Vivek RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cns Stimulants: DR Laith M Abbas Al-Huseini M.B.CH.B, M.SC., M.Res., PH.DDocument38 pagesCns Stimulants: DR Laith M Abbas Al-Huseini M.B.CH.B, M.SC., M.Res., PH.DHemantPas encore d'évaluation

- Research ProposalDocument11 pagesResearch Proposalcodybarrow10Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hills Like White ElephantsDocument9 pagesHills Like White ElephantsJosé JaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Excessive Use of Gadgets To The Students of Grade 10-ThriftinessDocument17 pagesEffects of Excessive Use of Gadgets To The Students of Grade 10-ThriftinessKanao Tsuyuri100% (1)

- Schedules of ReinforcementDocument7 pagesSchedules of ReinforcementBlue OrangePas encore d'évaluation

- Ordinary Test Ordinario Unit 3 B2+Document6 pagesOrdinary Test Ordinario Unit 3 B2+Estefania MagañaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nicotine and Its Overdose EffectsDocument4 pagesNicotine and Its Overdose EffectsahmedaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Levels of Care For Addiction TreatmentDocument4 pagesLevels of Care For Addiction TreatmentChanPas encore d'évaluation

- Amy Winehouse Cause of DeathDocument2 pagesAmy Winehouse Cause of Deathmazuki287350% (2)

- Abstinence Journal ReflectionDocument3 pagesAbstinence Journal Reflectionapi-451295416Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cinimatic Unisystem CompiledDocument189 pagesCinimatic Unisystem CompiledWurzelwerk100% (1)

- Kubla Khan Heaven and HellDocument8 pagesKubla Khan Heaven and HellRxyPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug AwarenessDocument42 pagesDrug AwarenessElmer AbesiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Shopping ManiaDocument15 pagesShopping Maniaabdakbar100% (6)

- 6 Classification of DrugsDocument6 pages6 Classification of DrugsDaddyDiddy Delos ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Chemistry Project On NicotineDocument19 pagesChemistry Project On NicotinePrashant Kumar63% (8)

- Advocates For Recovery BrochureDocument2 pagesAdvocates For Recovery BrochurePeer Coach Academy ColoradoPas encore d'évaluation

- Astrology of AddictionsDocument2 pagesAstrology of Addictionsanu056100% (1)

- Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesLesson Plangracezel cachuelaPas encore d'évaluation

- KrokodilDocument6 pagesKrokodilapi-253316831Pas encore d'évaluation

- Smoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearDocument12 pagesSmoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearBernardo Villavicencio VanPas encore d'évaluation

- Substance Abuse Group ProjectDocument9 pagesSubstance Abuse Group Projectapi-253915117Pas encore d'évaluation