Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Demons Dreamers and Madmen

Transféré par

শূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দার0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

268 vues17 pagesDemons, Dreamers, and Madmen: The Defense of Reason in Descartes's Meditations by Frankfurt, H.G.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDemons, Dreamers, and Madmen: The Defense of Reason in Descartes's Meditations by Frankfurt, H.G.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

268 vues17 pagesDemons Dreamers and Madmen

Transféré par

শূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারDemons, Dreamers, and Madmen: The Defense of Reason in Descartes's Meditations by Frankfurt, H.G.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 17

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

Harry G. Frankfurt: Demons, Dreamers, and Madmen

is published by Princeton University Press and copyrighted, 2007, by Princeton

University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form

by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information

storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading

and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any

network servers.

Follow links for Class Use and other Permissions. For more information send email to:

permissions@pupress.princeton.edu

1

Introduction

IntheTheaetetus,Platodescribesthinkingasaconversation

conductedbythesoulwithitself.

1

Thishassometimesbeen

takenasareasonforadmiringhisuseofthedialogueform.

Koyregoessofar,infact,astomaintainthatthedialogue

istheformpar excellence forphilosophicinvestigation,be-

causethoughtitself,atleastforPlato,isadialoguethesoul

holds with itself.

2

But a dialogue is not a conversation

with oneself. It is a conversation with other people. If

thinking is indeed internal discourse, then dialogue can

hardlybetheideallyappropriateliteraryforminwhichto

conveyit.Amuchmoreappropriatevehicleisthemedita-

tion, in which an author represents the autonomous give

andtakeofhisownsystematicreections.

Moral and religious meditations were published before

theseventeenthcentury,butDescarteswasthersttouse

theforminanexclusivelymetaphysicalwork.

3

Duringhis

lifetimehepublishedthreemajorphilosophicalbooks.One

ofthese,Principles of Philosophy,wasmeantasatextforuse

intheschools,anditsformwasdictatedbythisintention.

But in the Discourse on Method and in the Meditations,

Descartes was free to write philosophy as he liked. Both

1

189eand263e.

2

AlexanderKoyre,Discovering Plato (NewYork:ColumbiaUniver-

sityPress,1945),p.3n.

3

EtienneGilson,E

tudes sur le role de la pensee medievale dans la for-

mation du syste`me cartesien (Paris:J.Vrin,1951),pp.186187.

4 Chapter 1

booksareautobiographical.LikePlatosdialogues,theydo

notemasculatethephilosophicalenterprisebyseveringits

connection with the lives of men. Descartes differs from

Plato, however, in the way he solves one of the touchiest

problemsofphilosophicalwritingtoprotectthevitalin-

dividuality of philosophical inquiry without betraying the

anonymityofreason.

Plato never enters the dramatic scenes he creates. He

mayintendtosignifybythisself-effacementhisrefusalto

use the stage of inquiry for personal display.

4

There is a

certaintension,however,betweenhisconceptionofinquiry

andtheliterarygenrehechose.Platoinsiststhatphiloso-

phy and rhetoric are antithetical, but his dialogues would

have been lifeless if he had rigorously excluded rhetoric

fromthem.Ifthecharactersinadialoguearetoappearas

persons,andnotmerelyasdevicesforpunctuatingthetext,

rhetorical elements must naturally intrude into their dis-

coursejustastheydointotheconversationsofrealpeople.

Descartesavoidsthisdifcultybydecliningtoplacehis

inquiry within a social context. He does his thinking in

private,andnooneappearsinhisMeditations buthimself.

To be sure, his style is personal and sometimes even inti-

mate.Butwhilehewritesautobiography,thestoryhetells

isofhiseffortstoescapethelimitsofthemerelypersonal

andtondhisgenericidentityasarationalcreature.What-

everactuallymayhavebeenhismotivesinpublishingthe

Discourse anonymously, philosophically it was appropriate

forhimtodoso.Hisattitudetowardphilosophyisnicely

implicit in the paradox of an anonymous autobiography,

4

See Ludwig Edelstein, Platonic Anonymity, American Journal of

Philology,LXXXIII(1962),122.

Introduction 5

which serves to reveal a man but which treats the mans

identityasirrelevant.

Religious meditations are characteristically accounts of

a person seeking salvation, who begins in the darkness of

sinandwhoisledthroughaconversiontospiritualillumi-

nation.Whilethepurposeofsuchwritingistoinstructand

initiateothers,themethodisnotessentiallydidactic.The

author strives to teach more by example than by precept.

InabroadwaytheMeditations isaworkofthissort:Des-

cartess aim is to guide the reader to intellectual salvation

by recounting his own discovery of reason and his escape

thereby from the benighted reliance on his senses, which

hadformerlyentrappedhiminuncertaintyanderror.

InreadingtheFirstMeditationitisessentialtounder-

stand that while Descartes speaks in the rst person, the

identity he adopts as he addresses the reader is not quite

his own. Students of Descartes often fail to take into ac-

count the somewhat ctitious point of view from which

heapproacheshissubject,andthisfrequentlyleadstoseri-

ousmisunderstanding.AshebeginstheMeditations,Des-

cartessstanceisnotthatofanaccomplishedscholarwho

hasalreadydevelopedthesubtleandprofoundphilosophi-

cal position set forth in that work. Instead, he affects a

pointofviewhehaslongsinceoutgrownthatofsomeone

whoisphilosophicallyunsophisticatedandwhohasalways

beenguidedmoreorlessunreectivelyinhisopinionsby

commonsense.

Thisisnotverysurprising,ofcourse,inviewoftheauto-

biographical nature of his book. Descartess meditations

occurred years before he wrote the Meditations, and the

FirstMeditationrepresentsanearlystageofhisownphilo-

sophicalthinking.HemakesthisquiteexplicitintheCon-

6 Chapter 1

versation with Burman,whereheexplainsthatintheFirst

Meditation he is attempting to represent a man who is

rst beginning to philosophize, and where he discusses

some of the limitations by which the perspective and un-

derstanding of such a person are bound.

5

The lack of so-

phistication that Descartes affects consists essentially in a

failure to appreciate the radical distinction between the

senses and reason. Thus it concerns doctrine, not talent,

anditisbynomeansinconsistentwiththeresourcefulness

andingenuitythatDescartesdisplaysintheFirstMedita-

tion.Thetalentavailabletohimashestartshisinquiryis

his own. It is only the assumptions that govern his initial

stepsthatarena veandphilosophicallycrude.

ThispointisalsoimplicitinthemethodDescartesem-

ploystopresenthisideasintheMeditations.Hedescribes

this method in a well-known passage near the end of his

Reply to the Second Objections. There he distinguishes

between what he calls the analytic and the synthetic

methodsofproof,andheobservesthatinmyMeditations

I have followed analysis alone, which is the true and best

way of teaching.

6

When the synthetic method is used, a

systemofthoughtisformallyarrangedindeductiveorder:

denitions, axioms, and postulates are neatly laid out, as

in a geometry textbook, and each theorem is exhibited as

conclusivelydemonstrablefromthesematerials.Butthere

5

CharlesAdam,ed.,Entretien avec Burman (Paris:Boivin,1937),p.

64;CharlesAdamandPaulTannery,Oeuvres de Descartes (Paris:L.Cerf,

18971913),Vol.VII,p.156,ll.35.IwillhereafterrefertotheAdam

andTanneryeditionasAT.Thevolumewillappearinromannumeral,

thepagenumberwillfollowinarabic,throughout.

6

AT VII, 156, ll. 2123. E. S. Haldane and G. R. T. Ross, The

Philosophical Works of Descartes (NewYork:Dover,1955),Vol.II,p.49.

IwillhereafterrefertotheHaldaneandRosseditionasHR.

Introduction 7

isnoinklingofhowthematerialswerearrivedatorofhow

thevarioustheoremswerefoundtobederivablefromthem.

The work of discovery and creation is ignored, taken en-

tirely for granted, and attention is directed exclusively to

thecerticationofitsresults.

Descartesacknowledgesthesuitabilityofthismethodfor

theexpositionofasubjectlikegeometry,wheretheprimary

notionsinvolvedintheproofsarereadilygrantedbyall.

7

Heregardsitasquiteunsuitableinaworkdevotedtometa-

physics,however,eventhoughheisconvincedthatthepri-

marynotionsofmetaphysicaldiscourseareultimatelymore

intelligiblethanthoseofgeometry.Forwhiletheconcepts

hendsbasicinmetaphysicsareinherentlyveryclear,they

are discordant with the preconceptions to which we have

since our earliest years been accustomed.

8

If they are ad-

vanced abruptly, therefore, they are quite likely to be re-

jectedasinappropriateorimplausible.Itisaccordinglymost

desirabletopresenttheminsuchawaythatthereadercan

appreciatetheirsignicanceandrecognizetheirpriority.

This happens when the exposition is according to the

analytic method, which shows the true way by which a

thingwasmethodicallydiscovered.

9

Analyticaccountsare

designed not merely to evoke agreement but to facilitate

insight;theauthorinviteshisreaderstoreproducethefruit-

fulprocessesofhisownmind.Heguidesthemtoconstruct

ortodiscoverforthemselvestheconceptsandconclusions

which,bythesyntheticmethod,wouldbehandedtothem

ready-made.Forthisreasonanappropriateuseoftheana-

lytic method requires a relatively unsophisticated starting

7

HRII,49;ATVII,156,ll.2930.

8

HRII,50;ATVII,157,ll.1112.

9

HRII,48;ATVII,155,ll.2324.

8 Chapter 1

point. The reader cannot be supposed to possess already

the fundamental concepts of the subject at issue, or to be

from the start in a position to grasp the truths that the

inquiryissupposedtoattain.

Descartess method of exposition in the Meditations

obligeshimtoshowscrupulousrespectforthephilosophi-

calna veteofhisintendedreader.Ashedevelopshisargu-

menthemustnotrequireeithertheuseortheunderstand-

ingofmaterialsthatthetexthasnotalreadyprovidedand

that could be acquired legitimately only through philo-

sophical investigations the reader cannot be assumed to

have completed. He must take no step for which he has

failedtomakesuitablepreparation;atnostageofthework

mayhepresumeanygreaterphilosophicalprogressthanhe

himselfhasledhisreadertoachieve.

Descartes was of course fully aware of this. He insists

that he certainly tried to follow that order most strictly

intheMeditations;heputforwardrst[thosethings]that

mustbeknownwithoutanyhelpfromthethingsthatfol-

low, and all the rest are then arranged in such a way that

theyaredemonstratedsolelyonthebasisofthingspreced-

ingthem.

10

Nowthisprovidesavaluableprincipleforuse

in interpreting the Meditations. For it justies presuming

that there is an error in any interpretation according to

which Descartes is required to rely at a given point upon

philosophicalmaterialnotalreadydevelopedatsomeear-

lierstageinhispresentation.

NowoneofDescartessmostprovocativedoctrinesdoes

not appear in the Meditations at all. In a number of his

letters he maintains that what God can do is not limited

bythelawsoflogic,andthattheselawsare,infact,subject

10

HRII,48;ATVII,155,ll.1114.

Introduction 9

tothedivinewill.Thetruthsofmathematics,hewrites

toMersenne,

wereestablishedbyGodandentirelydependonHim,

as much as do all other creatures. To say that these

truthsareindependentofHimis,ineffect,tospeak

ofGodasaJupiterorSaturnandtosubjectHimto

theStyxandtotheFates. . . . You will be toldthatif

God established these truths He would be able to

change them, as a king does his laws; to which it is

necessarytoreplythatthisiscorrect. . . .

11

In another letter, to Mesland, Descartes says: the power

ofGodcanhavenolimits. . . . God cannothavebeende-

terminedtomakeittruethatcontradictionscannotbeto-

gether, and consequently He could have done the con-

trary.

12

There can be little doubt that Descartes actually

heldthisremarkabledoctrine.Butheneversetsitforthin

theMeditations,perhapsbecausehefeareditwoulddisturb

thetheologianswhosesupportortolerationhewasanxious

toenjoy.Itwouldthereforebequiteimpropertointerpret

the philosophical position he develops in the Meditations

insuchawaythathisviewsconcerningthedependenceof

the eternal verities on the will of God play an essential

roleinit.

In view of Descartess emphasis on the importance of

order in the Meditations, no advice could be worse than

that given by Prichard. After observing that Descartess

bookisextraordinarilyunequalandthatsomeparts...

deal with what is important and very much to the point

11

LettertoMersenne,15April1630;ATI,145,ll.713;145,l.28

146,l.1.

12

LettertoMesland,2May1644;ATIV,110.

10 Chapter 1

whileothersareveryarticialandunconvincing,Prichard

suggeststhat

theproperattitudeforthereaderandthecommenta-

toristoconcentrateattentiononwhatseemtheim-

portantpartsandtobotherverylittleabouttherest.

ForthatreasonIshallinfactconsidercloselycertain

portionswhichseemtomecentralandalmostignore

therest,andIwouldsuggestthatyoushoulddothe

sameinreadinghim.

13

Descartes would nothave been surprised bythis attitude;

in the Preface to the Meditations, in fact, he anticipates

beingreadmoreorlessasPrichardsuggests.Buthewarns

therethatthosewhodonotcaretocomprehendtheorder

andconnectionsofmyreasoningsandwhoareoutonlyto

prattleaboutisolatedpassages,asmanyareaccustomedto

do,willnotreceivemuchprotfromreadingthisessay.

14

Ifhisaccountofhisthoughtisviewedasformingamere

collection of philosophical atomsa compendium into

whichonemayplausiblydipatanypointtheresultwill

oftenbeafailuretograspwhathewishestoconvey.

IntheFirstMeditationDescartesdenesthephilosoph-

ical enterprise he proposes to undertake; he also sketches

andillustratestheprocedurebywhichheintendstocarry

it out. Without a thorough comprehension of what goes

oninthisMeditation,itisnotpossibletounderstandhis

conceptionofthetasksofmetaphysicsortoevaluateintelli-

gently his solutions to the problems he considers in his

book. This comprehension may seem easy to come by.

13

H. A. Prichard, Knowledge and Perception (Oxford: Clarendon

Press,1950),p.72.

14

HRI,139;ATVII,9,l.2810,l.2.

Introduction 11

Afterall,theFirstMeditationhasareputationforlucidity

and its arguments are very familiar. In fact, however, the

Meditation is far from fully accessible to a casual reading

andimportantaspectsofitareveryoftenmisunderstood.

DescarteshimselfremarksoftheMeditations asawhole

that on many things it often scarcely touches, since they

areobvioustoanyonewhoattendssufcientlytothem.

15

Butitismoreprudenttotakethisstatementasawarning

than as a reassurance, particularly in view of Descartess

admonitionthatifeventheveryleastthingputforwardis

notnoted,thenecessityoftheconclusionsfailstoappear.

16

Becauseofitsbasicimportance,andbecauseoftherather

deceptive clarity inclining many readers to overlook its

complexities, the First Meditation needs to be examined

withspecialcare.

MyaiminPartOneofthisbookistogiveanaccount

oftheviewsDescartesdevelopsintheFirstMeditationand

of the arguments by which he supports them. When he

says or does something that seems questionable, I shall

sometimesattempttoshowthathisstatementorhisproce-

dure ismore plausible thanit looks.Descartess brilliance

is at times too hasty and impatient; there are gaps in his

expositionthatheneglectedordisdainedtoll.Especially

whenhisfailuresseemmostblatantanddamaging,Ishall

endeavorwhenever,atleast,Icanseehowtooffersav-

ing explanations which he himself might reasonably have

provided. Whether these explanations actually succeed in

savinghimfromcriticismis,ofcourse,anothermatter.

IngeneralIshallbelessconcernedwithexploringand

evaluating the details of Descartess views for their own

15

HRII,49;ATVII,156,ll.35.

16

HRII,4849;ATVII,156,ll.13.

12 Chapter 1

sakes than with clarifying the structure of the inquiry he

conductsintheFirstMeditation.Ihaveanulteriorpurpose

inthis.PartTwoofthisbookislargelydevotedtoelaborat-

ing an interpretation of Descartess discovery and valida-

tionofreason.Inseekingtounderstandthenatureofthe

questionthathefounditnecessarytoaskaboutreason,and

theanswertoitthathethoughtitpossibletogive,Ihave

founditusefultorecognizethatintheFirstMeditationhe

raisesaquestionofthesamesortaboutthesensesandtries

(unsuccessfully,ofcourse)toprovidethesamesortofan-

swertoit.Thisparallelismbetweenhisdiscussionsofthe

sensesandofreasonis,indeed,partoftheevidenceforthe

thesisaboutthelatterthatIdevelopinPartTwo.Thefact

thatDescartesseeshisproblemintheFirstMeditationin

a certain way increases, I believe, the plausibility of my

claimthatheseesthesimilarproblemthathefaceslaterin

the Meditations in a similar way. It is therefore important

formyargumentinPartTwo,thoughperhapsnotdecisive,

thatImakeclearjustwhatgoesonintheFirstMeditation.

PartOnepresupposesthatthereaderisfamiliarwiththe

FirstMeditation.Here,then,isatranslationofit.

FirstMeditation

CONCERNINGTHOSETHINGSTHAT

CANBECALLEDINTODOUBT

It is now several years since I observed how many false

thingsIacceptedastrueearlyinmylife,andhowdubious

allthosethingsarethatIafterwardsbuiltuponthem;and,

therefore, that everything must be thoroughly overthrown

foronceinmylifeand begunanewfromtherstfounda-

tions,ifIwantevertoestablishanythingsolidandperma-

nentinthesciences.Butthetaskseemedenormous,andI

Introduction 13

awaited a time of life so mature that no time better suited

forundertakingsuchstudieswouldfollow.Onthataccount

IhavedelayedsolongthatfromnowonIwouldbeatfault

if I were to use up in deliberating the time left for acting.

Today, then, I have opportunely freed my mind from all

cares andarranged a periodof assured leisure formyself. I

am quite alone. At last I shall have time to devote myself

seriouslyandfreelytothisgeneraloverthrowofmyopinions.

For this purpose, however, it will not be necessary for

me to show that all my opinions are falsewhich, very

likely,Icouldnevermanagetodo.Butreasonalreadyper-

suadesmethatassentmustbewithheldnolessscrupulously

from things that are not entirely certain and indubitable

[indubitata]thanfromthingsthatareplainlyfalse.Forthe

rejectionofallmyopinions,therefore,itwillbeenoughif

I discoverin eachone ofthem somereason fordoubting.

Andtheyneednotbegoneoveronebyoneforthatpur-

posethatwouldbeanendlesstask.Butwhenthefounda-

tions have been undermined, whatever has been built up

uponthemwillcollapseofitself.HenceIshallimmediately

attack thevery principleson whicheverything Ionce be-

lieveddepended.

Unquestionably,whatever Ihave accepteduntil nowas

true inthe highest degreeI have received eitherfrom the

sensesorthroughthesenses.Fromtimetotime,however,

I have caught them deceiving, and it is prudent never to

trustentirelyinthosewhohavecheatedusevenonce.

Butitmaybethateventhoughthesensesdodeceiveus

fromtimetotimeregardingthingsthatareverysmallortoo

faraway,thereareneverthelessmanyotherthingsregarding

whichoneplainlycannotdoubteventhoughtheyarede-

rived from those same senses: for example, that I am now

here, sitting by a re, dressed in a winter cloak, touching

14 Chapter 1

this paper with my hands, and the like. Indeed, by what

reasoningcoulditbedeniedthattheseveryhandsandthis

wholebodyofmineexist?UnlessperhapsIweretoconsider

myself to be like certain madmen, whose brains are being

broken down by a vapor from the black bile, a vapor so

perverse that they calmly assert that they are kings (when

they are in extreme poverty), or that they are dressed in

purple(whentheyarenaked),orthattheyhaveearthenware

headsorthattheyarenothingbutpumpkins,orblownout

of glass. But they are madmen, and I should seem no less

madifIweretotaketheminanywayasamodelformyself.

Howeminentlyreasonable!AsifIwerenotamanwho

isusedtosleepingatnightandtoexperiencingindreams

all those very thingsor, from time to time, things even

lessprobablethantheonessuchmadmenexperience,while

theyareawake.Indeed,howoftenamIpersuadedduring

my nightly rest of these familiar thingsthat I am here,

wearingacloak,sittingbyarealthoughIlieundressed

betweenthesheets.

But now, at any rate, I am surely looking at this paper

withwakefuleyes,thisheadthatIamshakingisnotasleep,

Iamdeliberatelyandknowinglyextendingthishand,and

Iamhavingfeelings.Asleepingmanwouldnothavesuch

distinctexperiences.

AsifIdidnotrecallhavingbeendeludedatothertimes

bysimilarthoughtsindreams!NowthatIthinkoverthese

mattersmoreattentively,Iseesoplainlythatonecannever

by any certain indications distinguish being awake from

dreamingthatIamamazed.Andthisveryamazemental-

mostconrmstheconjecturethatIamdreaming.

Wellthen,supposethatwearedreaming,andthatthese

thingsthatweopenoureyes,moveourhead,extendour

handsarenottrue,andeventhatwedonotactuallyhave

Introduction 15

hands or a body. Even so it surely must be acknowledged

that things seen during sleep are like painted representa-

tions,whichcouldnotbeformedexceptin thelikenessof

truly real things. And so it must be acknowledged that at

least things of these kindseyes, head, hands, and the

whole bodyexist as real things, not imaginary, but true.

Forasamatteroffactevenwhenpaintersthemselvesstrive

to depict sirens and satyrs with the most extraordinary

forms,theycannotprovidethemwithnaturesthatarenovel

ineveryrespect,butcanonlymixtogetherthepartsofdif-

ferentanimals.Oreveniftheyshouldhappentothinkup

somethingsonovelthatnothingatalllikeithadbeenseen,

and thus something that is entirely ctitious and false, at

leastthecolorsoutofwhichtheycomposeitwouldsurely

have to be true colors. And for the same reason, even if

things of these kindseyes, head, hands, and the like

couldbeimaginary,stillitmustbeacknowledgedthatcer-

tain other simpler and more universal things are true and

that out of these true colors are formed all the true and

thefalserepresentationsofrealthingsinourthought.These

seemtobeofthatsort:corporealnatureingeneralandits

extension,theshapeofextendedthings,thequantity(orthe

size and number) of those things, the place in which they

exist,thetimethroughwhichtheylast,andthelike.

Inthelightoftheseconsiderations,perhapsweareright

toconcludethatphysics,astronomy,medicine,andallother

disciplines that depend on a consideration of composite

thingsareindeeddoubtful;andthatarithmetic,geometry,

andothersofthatsort,whichtreatonlyofthesimplestand

mostgeneralthingsandscarcelycarewhetherthosethings

areinnatureornot,containsomethingcertainandindubi-

table [indubitati]. For whether I am awake or asleep, two

and three joined together are ve, and a square does not

16 Chapter 1

havemorethanfoursides.Anditseemsthatitcannotbe

the case that truths so evident should incur any suspicion

offalsity.

Neverthelessthereisacertainopinion,longestablished

inmymind,thatthereisaGodwhocandoeverythingand

bywhomIhavebeencreatedasIam.NowhowdoIknow

hehasnotbroughtitaboutthatthereisnoearthatall,no

sky, no extended thing, no shape, no size, no place, and

thatallthesethingsshouldneverthelessseemtometoexist

justastheydonow?Andwhatismore,justasIsometimes

judge that others are mistaken about the very things that

theyconsiderthemselvestoknowmostperfectly,howdoI

knowthatGodhasnotbroughtitaboutthatIammistaken

everytimeIaddtwoandthreetogetherorcountthesides

of a square or [do something even simpler], if anything

simplercanbeimagined?

And yet, perhaps God willed that I should not be de-

ceivedinthatfashion,forheissaidtobesupremelygood.

But if it should be inconsistent with his goodness to

have created me so that I am always mistaken, it would

seem no less foreign to his goodness to allow that I

should be sometimes mistaken, which, however, cannot

bemaintained.

Of course, there may be some who prefer to deny so

powerfulaGodratherthantobelievethatallotherthings

areuncertain.Butletusnotopposethem,andletusgrant

thatallthisregardingGodisctitious.Letthemsuppose

thatIhavebecomewhatIambyfate,orbychance,orby

aconnectedseriesofthings,orinanyotherwayyouplease.

Sinceitseemstobeakindofimperfectiontobemistaken

andtoerr,thelesspowertheyascribetotheauthorofmy

origin,themoreprobableitwillbethatIamsoimperfect

thatIamalwaysmistaken.

Introduction 17

Icertainlyhavenoresponsetothesearguments.Onthe

contrary,Iamnallyforcedtoacknowledgethatofthose

things I formerly considered to be true there is nothing

regarding which it is not legitimate to doubt. And this

is not through lack of consideration or frivolity, but for

valid and meditated reasons. If I want to nd something

certain, therefore, assent must be carefully withheld from

those things one after another no less than from things

obviouslyfalse.

Butitisnotyetenoughtohaveobservedthesethings;

I must be careful to bear them in mind. For the familiar

opinionscomebackagainandagainanddominatemybe-

lief,whichistiedtothemevenentirelyagainstmywillby

long use and the privilege of intimate acquaintance. Nor

willIevergetoutofthehabitofassentingtoandtrusting

in them as long as I take them to be as they really are:

doubtfulinaway,tobesure(ashasjustnowbeenshown),

but nonetheless highly probableopinions that it is far

morereasonabletobelievethantodeny.

Thatiswhy,inmyview,Ishallnotbeactingincorrectly

if,withmywillplainlysetinacontrarydirection,Ideceive

myselfandpretendforawhilethattheyarealtogetherfalse

andimaginary.Thennally,thescalesbeingbalancedwith

prejudicesonbothsides,nobadhabitwillanylongertwist

myjudgmentawayfromtherightperceptionofthings.For

Iknowthatnodangerorerrorwillensueduringthattime

and that my disbelief cannot be overindulged, since I am

nowcommittednottoactingbutonlytoknowing.

I will suppose, therefore, not a supremely good God,

the source oftruth, but some evil spirit whois supremely

powerfulandcunningandwhohasexpendedallhisenergy

indeceivingme.Iwillsupposethatthesky,theair,earth,

colors,shapes,sounds,andallexternalthingsarenothing

18 Chapter 1

butthedelusionsofdreamsbymeansofwhichhehasset

trapsformycredulity.Iwillconsidermyselfashavingno

hands,noeyes,noesh,noblood,nosensesofanykind,

but as thinking falsely that I have all those things. I will

remainrmlyxedinthislineofthought[meditatio]and

thus,evenifitisnotinmypowertoknowanythingtrue,

stillthisisinmypowerIwillatleastnotassenttoany-

thing false. With rm resolution I will be on my guard

so thatthe deceiver, however powerful,however cunning,

cannottrickmeinanyway.

Butthisisalaboriousundertaking,andakindoflaziness

reduces me to the ordinary way of life. Just as a prisoner

who happened to be enjoying an imaginary liberty in

dreamsisafraidtowakeupwhenhelaterbeginstosuspect

that he is asleep, and readily connives with the agreeable

illusions, so I willingly slide back into my old opinions. I

dreadtobeawakenedlestmypeacefulrestshouldbesuc-

ceeded by a laborious wakefulness that would have to be

spentnotinthelight,butinthemidstoftheinextricable

darknessofthedifcultiesthathavejustbeenraised.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Dramatic Form and Philosophical Content in Plato's Dialogues Arthur A. Krentz PDFDocument17 pagesDramatic Form and Philosophical Content in Plato's Dialogues Arthur A. Krentz PDFhuseyinPas encore d'évaluation

- Plato's Idea of PhilosophyDocument18 pagesPlato's Idea of PhilosophyAkif Abidi100% (1)

- Demons, Dreamers, and Madmen: The Defense of Reason in Descartes's MeditationsD'EverandDemons, Dreamers, and Madmen: The Defense of Reason in Descartes's MeditationsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (4)

- D. C. SchindlerDocument11 pagesD. C. SchindlerAlexandra DalePas encore d'évaluation

- Burger Ronna - The Phaedo - A Platonic Labyrinth - Yale University Press (1984) PDFDocument299 pagesBurger Ronna - The Phaedo - A Platonic Labyrinth - Yale University Press (1984) PDFHotSpirePas encore d'évaluation

- M-01.Plato's Philosophical Concepts PDFDocument15 pagesM-01.Plato's Philosophical Concepts PDFAshes MitraPas encore d'évaluation

- Great Thinkers in 60 Minutes - Volume 1: Plato, Rousseau, Smith, Kant, HegelD'EverandGreat Thinkers in 60 Minutes - Volume 1: Plato, Rousseau, Smith, Kant, HegelPas encore d'évaluation

- Descartes and The Ontology of Subjectivity - B.C. FlynnDocument21 pagesDescartes and The Ontology of Subjectivity - B.C. FlynnFelipePas encore d'évaluation

- PHILO 2 (Definition of Philosophy Branches of Philosophy)Document19 pagesPHILO 2 (Definition of Philosophy Branches of Philosophy)Edward Amoyen AbellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Derrida and The Philosophical History of Wonder: Genevieve LloydDocument19 pagesDerrida and The Philosophical History of Wonder: Genevieve LloydNikola TatalovićPas encore d'évaluation

- Socrates Thesis of What Is GoodDocument5 pagesSocrates Thesis of What Is GoodOnlinePaperWritersCanada100% (2)

- A Hibrid Techne of The SoulDocument17 pagesA Hibrid Techne of The SoulmartinforcinitiPas encore d'évaluation

- Love's Reason From Heideggerian Care to Christian CharityDocument11 pagesLove's Reason From Heideggerian Care to Christian CharityDante KlockerPas encore d'évaluation

- Landry Aaron J 2014 PHDDocument207 pagesLandry Aaron J 2014 PHDKATPONSPas encore d'évaluation

- (PDF) Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human PersonDocument1 page(PDF) Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human PersonRic Allen GarvidaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2010 Eugenio Benitez InterpretationDocument18 pages2010 Eugenio Benitez InterpretationAlice SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- On Philosophical Style by Brand BlandshardDocument17 pagesOn Philosophical Style by Brand Blandshardenieves78100% (1)

- Malabou PDFDocument13 pagesMalabou PDFdicoursfigurePas encore d'évaluation

- Dialectical Thinking: The Capacity of the Mind to Rise Above ItselfDocument8 pagesDialectical Thinking: The Capacity of the Mind to Rise Above ItselfpalzipPas encore d'évaluation

- The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument13 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University PressTeiaPas encore d'évaluation

- DialecticAsAMysticalDiscipline RevDocument9 pagesDialecticAsAMysticalDiscipline RevMicaela BonacossaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparison of Plato's PhaedoDocument12 pagesA Comparison of Plato's PhaedonewianuPas encore d'évaluation

- Fred Moten The Touring MachineDocument37 pagesFred Moten The Touring Machinemanuel arturo abreuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard ProblemDocument5 pagesThe Hard ProblemHayzeus00Pas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Questions and Ancient AnswersDocument2 pagesContemporary Questions and Ancient AnswerspoisonriverPas encore d'évaluation

- Ronna Burger The Phaedo A Platonic Labirynth 1985Document149 pagesRonna Burger The Phaedo A Platonic Labirynth 1985André DecotelliPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Intentionality and The Myths of The GivenDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Intentionality and The Myths of The GivenPickering and ChattoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fernando Pessoa's Philosophical PersonasDocument12 pagesFernando Pessoa's Philosophical PersonasKevin PinkertonPas encore d'évaluation

- Uts PhilosophersDocument16 pagesUts PhilosophersWinly Blanco TortorPas encore d'évaluation

- The Platonic Philosophy 2022Document7 pagesThe Platonic Philosophy 2022Motseki Dominic ManonyePas encore d'évaluation

- Harold Cherniss and the Study of PlatoDocument12 pagesHarold Cherniss and the Study of PlatoOevide SeinPas encore d'évaluation

- Brenkman - The Other and The OneDocument62 pagesBrenkman - The Other and The OneJoan LubinPas encore d'évaluation

- Against RationalismDocument27 pagesAgainst RationalismsagarnitishpirtheePas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding the Philosopher's Love of WisdomDocument5 pagesUnderstanding the Philosopher's Love of WisdomLeonelynmerza33% (3)

- 1Document2 pages1Lhuna Khem TraigoPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Philosophy, Inc. The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific MethodsDocument11 pagesJournal of Philosophy, Inc. The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methodsbennyho1216Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy Textbook Chapter 01Document22 pagesPhilosophy Textbook Chapter 01Sukhveer SangheraPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes in Interpreting Plato's DialoguesDocument27 pagesNotes in Interpreting Plato's DialoguesElevic PernisPas encore d'évaluation

- POSITION PAPER (Pearlwines)Document7 pagesPOSITION PAPER (Pearlwines)Lorraine Claire WinesPas encore d'évaluation

- Nasruddin Hodja - A Master of The Negative WayDocument11 pagesNasruddin Hodja - A Master of The Negative WaySeyedAmir AsghariPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper On PlatoDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Platoafnkaufhczyvbc100% (1)

- Methods in Philosophizing Lesson 1 Part 2Document14 pagesMethods in Philosophizing Lesson 1 Part 2Sebastian CamagongPas encore d'évaluation

- Raoul Mortley What Is Negative Theology The Western OriginDocument8 pagesRaoul Mortley What Is Negative Theology The Western Originze_n6574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Oedipus Constructed: A Theory of AssimilationDocument2 pagesOedipus Constructed: A Theory of AssimilationPedro Roa OrtegaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy ReviewrDocument14 pagesPhilosophy ReviewrHershe TabernillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Intelligibles are not Outside the IntellectDocument13 pagesWhy Intelligibles are not Outside the IntellectbrizendinePas encore d'évaluation

- Derrida's and Levinas' convergences in critiquing metaphysics (39Document2 pagesDerrida's and Levinas' convergences in critiquing metaphysics (39Ryan AlisacaPas encore d'évaluation

- (Daniel Cohen) Arguments and Metaphors in PhilosopDocument234 pages(Daniel Cohen) Arguments and Metaphors in PhilosopMeral KızrakPas encore d'évaluation

- Heidegger Die Frage Nach Dem Sinn Des SeinsDocument35 pagesHeidegger Die Frage Nach Dem Sinn Des SeinsGlenn Rey AninoPas encore d'évaluation

- Vicki Kirby - Quantum Anthropologies - Life at Large-Duke University Press (2011)Document181 pagesVicki Kirby - Quantum Anthropologies - Life at Large-Duke University Press (2011)Aadhya BodhisattvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Zaborowski - Plato & Max Scheler On The Affective World PDFDocument17 pagesZaborowski - Plato & Max Scheler On The Affective World PDFAlvino-Mario FantiniPas encore d'évaluation

- HOF - Hale.derrida and VanTil.6.30.04Document18 pagesHOF - Hale.derrida and VanTil.6.30.04Christopher CannonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Laws of Thought - Issue 106 - Philosophy NowDocument2 pagesThe Laws of Thought - Issue 106 - Philosophy NowBanderlei SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- DeconstructionDocument4 pagesDeconstructionidaidutPas encore d'évaluation

- Transformative Philosophy A Study of Sankara Fichte and HeideggerDocument199 pagesTransformative Philosophy A Study of Sankara Fichte and HeideggerdositheePas encore d'évaluation

- Euthyphro PDFDocument16 pagesEuthyphro PDFDianaNakashimaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Ulysses RequiresDocument65 pagesWhat Ulysses Requiresশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Ulisses JR WorkoutDocument2 pagesUlisses JR WorkoutJake OrthweinPas encore d'évaluation

- TASC Test Practice Items - MathDocument16 pagesTASC Test Practice Items - Mathশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- James Joyce, Ulysses: January 1984Document56 pagesJames Joyce, Ulysses: January 1984শূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Anapanasatisuttam PDFDocument45 pagesAnapanasatisuttam PDFZaid Lopez VeynaPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 Pack Abs E-BookDocument15 pages6 Pack Abs E-BookKushagra KrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bodybuilding Abs WorkoutDocument2 pagesBodybuilding Abs Workoutশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Abdominal WorkoutDocument1 pageAbdominal WorkoutdangerdaveballPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviews: Theory of SeeingDocument5 pagesReviews: Theory of Seeingশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Full Body Workout B PDFDocument17 pagesFull Body Workout B PDFDiogo Proença74% (23)

- Penguin Random House Internship Program 12.2021Document1 pagePenguin Random House Internship Program 12.2021শূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- AbdominalsDocument13 pagesAbdominalsBeniamin CociorvanPas encore d'évaluation

- Compaso2011 21 SchalkDocument14 pagesCompaso2011 21 SchalkTaim EngPas encore d'évaluation

- FULL BODY WORKOUT A PDF Jeremyethier PDFDocument15 pagesFULL BODY WORKOUT A PDF Jeremyethier PDFGaston.R100% (1)

- Biswarup Das - SunyataaDocument5 pagesBiswarup Das - Sunyataaশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Pearson Chapter 1Document57 pagesPearson Chapter 1শূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Bodybuilding Abs WorkoutDocument2 pagesBodybuilding Abs Workoutশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Quantum Field Theory for Mathematicians ExplainedDocument48 pagesQuantum Field Theory for Mathematicians Explainedশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Front End Web Developer: Course SyllabusDocument10 pagesFront End Web Developer: Course Syllabusramarao_pand100% (1)

- Boss Everline's Workout LogDocument2 pagesBoss Everline's Workout Logশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism (2 Vol Set) (Gnv64)Document912 pagesThe Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism (2 Vol Set) (Gnv64)Shari Boragine88% (8)

- Review of Iser's Reception Theory PDFDocument5 pagesReview of Iser's Reception Theory PDFsarajamalsweet100% (1)

- Tolstoy and Nietzsche Comparison PDFDocument17 pagesTolstoy and Nietzsche Comparison PDFশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Archetypal CriticismDocument19 pagesArchetypal Criticismশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Allah UpanishadDocument2 pagesAllah Upanishadশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Spivak (2004) - Righting WrongsDocument59 pagesSpivak (2004) - Righting WrongsMartha SchwendenerPas encore d'évaluation

- Three Women's Texts and A Critique of ImperialismDocument20 pagesThree Women's Texts and A Critique of Imperialismশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy Bits On NietzscheDocument26 pagesPhilosophy Bits On Nietzscheশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- RG Veda - BreretonDocument14 pagesRG Veda - Breretonশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Katha Upanishad - MascaroDocument8 pagesKatha Upanishad - Mascaroশূর্জেন্দু দত্ত-মজুম্দারPas encore d'évaluation

- Data Analysis and Modeling Bcis New CourseDocument2 pagesData Analysis and Modeling Bcis New CourseSpandan KcPas encore d'évaluation

- Ordinary AnnuityDocument2 pagesOrdinary Annuityolivia leonorPas encore d'évaluation

- Sol MT PDFDocument4 pagesSol MT PDFMohamed AttarPas encore d'évaluation

- Signal Processing For Intelligent Sensor Systems With MATLAB 2nd Edition PDFDocument664 pagesSignal Processing For Intelligent Sensor Systems With MATLAB 2nd Edition PDFwijdijwij100% (1)

- Linear CongruencesDocument6 pagesLinear CongruencesJUNALYN MANATADPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 005 Cost Behavior AnalysisDocument153 pagesChapter 005 Cost Behavior AnalysisKim NgânPas encore d'évaluation

- HNHS NLC Class Program v.3Document2 pagesHNHS NLC Class Program v.3Moriah Rose BetoPas encore d'évaluation

- CHEN64341 Energy Systems Coursework Andrew Stefanus 10149409Document12 pagesCHEN64341 Energy Systems Coursework Andrew Stefanus 10149409AndRew SteFanus100% (1)

- Newton's Second Law LabDocument2 pagesNewton's Second Law LabMichael NPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture13 ADCS TjorvenDelabie 20181111202Document126 pagesLecture13 ADCS TjorvenDelabie 20181111202ahmed arabPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Image Quality Using LANDSAT 7Document9 pagesAnalysis of Image Quality Using LANDSAT 7sinchana G SPas encore d'évaluation

- 3rd Grade Worksheets - Week 11 of 36Document110 pages3rd Grade Worksheets - Week 11 of 36Kathy RunklePas encore d'évaluation

- Digital Signal Generation and Spectral Analysis LabDocument4 pagesDigital Signal Generation and Spectral Analysis LabPette MingPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice MCQs For Mass, Weight and Density, Work, Energy and Power - Mini Physics - Learn Physics OnlineDocument4 pagesPractice MCQs For Mass, Weight and Density, Work, Energy and Power - Mini Physics - Learn Physics OnlinekarpeoPas encore d'évaluation

- Calcualtion INERTIA BASESDocument12 pagesCalcualtion INERTIA BASESJomyJose100% (1)

- CS188 Midterm 1 Exam with AI Search and Sudoku ProblemsDocument14 pagesCS188 Midterm 1 Exam with AI Search and Sudoku ProblemsMuhammad AwaisPas encore d'évaluation

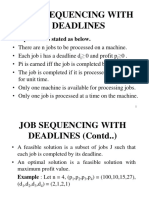

- Job Sequencing With The DeadlineDocument5 pagesJob Sequencing With The DeadlineAbhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Universal Playfair Cipher Using MXN MatrixDocument5 pagesUniversal Playfair Cipher Using MXN MatrixIJEC_EditorPas encore d'évaluation

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics 10: A. Preliminary/Routinary ActivityDocument12 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics 10: A. Preliminary/Routinary ActivityWilson MoralesPas encore d'évaluation

- Sense and ReferenceDocument10 pagesSense and ReferenceRonald ChuiPas encore d'évaluation

- 17ME61-Scheme and SyllabusDocument3 pages17ME61-Scheme and SyllabusSukesh NPas encore d'évaluation

- PhysicsDocument18 pagesPhysicsSheraz KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Management Professional WorksheetDocument24 pagesProject Management Professional WorksheetSowmya N Maya100% (1)

- Basic Terms in StatisticsDocument13 pagesBasic Terms in Statisticskmay0517Pas encore d'évaluation

- ch16 PDFDocument18 pagesch16 PDFShanPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Probability Worksheet PDFDocument20 pagesBasic Probability Worksheet PDFFook Long WongPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Bahasa Inggris 2Document16 pagesJurnal Bahasa Inggris 2Gabriel ArmandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre-Calculus: Quarter 1 - ModuleDocument21 pagesPre-Calculus: Quarter 1 - ModuleJessa Varona JauodPas encore d'évaluation

- Icse 10 Computer Chinni TR NoteDocument8 pagesIcse 10 Computer Chinni TR NoteAD SOLUTIONSPas encore d'évaluation

- SyllabusDocument228 pagesSyllabusGOKUL SPas encore d'évaluation