Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Semco Case Study

Transféré par

ioeuserCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Semco Case Study

Transféré par

ioeuserDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SEMCO (A): A MOST UNUSUAL WORKPLACE

Reference no 300-153-1

Technical assistance

t +44 (0) 1234756410, e ecch@ecch.com

North American customers:

t +1 781 2395884, e ecchusa@ecch.com

Document ID: 11020-1388-16C1B-00016Cl E

the case for learning

Distributedbyeech, UKi!lnd USA

www.eech.eem

All rights reserved

NorthAmerica

t +17812395884

f +1 781 2395885

e ecchuseeecch.com

Rest oftheworld

t +44 {Djl 234 750903

f +44 (0)1234 751125

e eccheecco.ccm

GRADUATE SCHOOL OF

MANAGEMENT

UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN

AUSTRALIA

300-153-1

o

U

Semco 'A':

A Most Unusual Workplace

This case was writtenby Fernando Chaddad, Managerat AndersenConsulting in

Sao Paulo, Brazil, under the supervision ofProfessor GaryJ Stockport, Graduate

School ofManagement, University of Western Australia. It is intendedto be usedas

the basisfor class discussion rather thanto illustrate either effective or ineffective

handlingofa management situation.

The case was compiledfrom publishedsources.

2001 GJ Stockport and F Chaddad, University of Westem Australia, Perth, Australia.

ef'J:iJ' -?o Distributedby The EuropeanCase ClearingHouse, England andUSA.

;: North America, phone: +1 781 239 5884, fax: +1 781239 5885, e-mail: ECCHBabson@aol.com.

Air Rest of the World, phone: +44 (0)1234 750903, fax: +44 (0)1234751125, e-mail: ECCH@craufield.ac.uk:.

C(.:t All rights reserved. Printed in UKand USA. Web Site: http://www.ecch.cranfield.ac.lIk.

, c'

300-153-1

Introduction

Semco is a small business located in an old industrial district in Sao Paulo, Brazil, with 2000revenues

approaching US$ lOOm and a direct staff of less than 300. It manufactures pumps, dishwashers, digital

scanners, mixers for anything from bubble gum to rocket fuel, and cooling units. Since the early 1990's,

Semco has been crawled over by the media and hundreds of curious corporations, including 150 of the

Fortune top 500 American companies.

Why does such a small company generate such a great amount of publicity? Ricardo Semler, the

Harvard-educated Semco CEO who was only in his early 20' s when he took over the company in 1980,

explains: "At Semco, the basic question we work on is: how do you get people to want to come to work

on a grey Monday morning? This is the only parameter we care about, which is 100%a motivation

issue. Everything else - quality, profits, growth - will fall into place if enough people are interested in

coming to work on Monday morning." (1)

Semco's reputation as a most unusual workplace has been projected internationally. Semco prides itself

on being a democratic, transparent place with little controls as each individual is responsible for his or

her own actions. In Brazil, thousands of applicants swamp Semco every time a job opening is made

public. Semler himself has been twice awarded the prize of Brazil's "Most Admired Business Leader".

Abroad, Semler has gained a guru-like reputation in the business speakers' circle, sharing the

microphone in the 1997World Masters of Business Seminar with Lee Iacocca, Norman Schwarzkopf

and Stephen Covey.

The democracy that permeates Semco seems to work. According to Semler, who himself owns 90% of

Semco: "Look at the results. Productivity is up seven-fold, and profits are up five-fold. We took a

moribund company and made it thrive, chiefly by refusing to squander our g r ~ s t asset: people." (2)

Company Background

Antonio Curt Semler was born in Vienna in 1912. Upon graduation from Vienna's Polytechnic as an

engineer, he accepted a position with DuPont company in a chemicals and textiles plant in Argentina.

By the early 1950's, he had moved to Brazil and had secured a patent for a centrifuge which could

separate lubricating oil from vegetables. Hence Semco, a contraction of Semler & Company, was

started inSao Paulo in 1953.

2

300-153-1

Fortunately for this one-product company, the centrifuge became a market leader. Three Brazilian

partners then joined Semco with badly needed capital and a knowledge of the country. The 1960's were

a time of fast growth for the Brazilian economy, and Semco was well positioned to take advantage of

the favourable scenario. As the Brazilian government made public through a National Shipbuilding

Plan its intention to spur shipbuilding in the country, Semco signed partnership agreements with two

British pump manufacturers and became a major marine pump supplier.

By1980, almost 90% of Semco's revenues were related to marine products such as pumps, components

for propellers, and water-oil separators for ship engines. Sales had been stable at US$4m for several

years. As the early-1980's recession loomed in Brazil, the shipbuilding industry was especially battered,

much like any other capital-goods industry. At Semco, the business slowdown was severe enough to

jeopardise Semco's very existence. Semco management spent much of 1980 in search of bank loans to

keep afloat, and even considered selling assets.

Ricardo Semler Steps In

It was in this difficult period for Semco that Ricardo Semler, then aged 20, joined Semco as his father

and Semco founder, Antonio Curt Semler, had expected.

Ricardo Semler, who in his own words "spent much of [his] adolescence playing rock & roll in a band,

was shocked by the oppression [... ] when [he] first started working at Semco (3)" in the purchasing

department at age 16. "The amount of rules and procedures numbed me. I couldn't help thinking that

Semco could be run differently, [... ] without keeping track of whether people were late, without all

these numbers and rules." (3) After graduating from Sao Paulo's prestigious State Law School, he

rejoined Semco in 1980. Soon thereafter, his father would transfer to him the majority of Semco shares

as well as the responsibility to run the business. Upon taking charge, young Semler's first action was to

remove more than half of those who had belonged to his father's trusted management team. Several

years after being in charge of Semco, Semler applied to undertake an MBA at Harvard Business School

but he was turned down on two occasions. He would later undergo executive training at Harvard,

spending three stints of one month per year there over a three-year period.

3

300-153-1

In the early 1980's, Semco needed orders badly amidst a deep recession. However, business was

unlikely to come from the shipping industry, then in complete standstilL Thus, Ricardo Semler and an

experienced new hire in the sales department named Harro Heyde set out to broaden Semco's product

line. They would convince manufacturers around the world to let Semco manufacture their pumps and

mixers in Brazil. By 1982, Semco was cash flow positive again and able to payoff its debt.

After this lesson, Semler decided to avoid dependency on one industry, thus diversifying away from

marine equipment through acquisitions. For US$ 0.5m, Semco acquired two businesses from Asea

Brown Boveri and Merck, respectively. The first acquisition was Flakt, which manufactured

refrigeration equipment for ships and ventilation systems for marine engine rooms. The second

acquisition was BAC (Baltimore Aircoil), a company that manufactured air-conditioning equipment.

Along with the two acquisitions came two new plants and 120 people. By 1984, another acquisition

followed: the Hobart plant, a Dart & Kraft Brazilian business unit with a headcount of 150 that

manufactured dishwashers, fryers, scales and slicers. The period that followed the Semco acquisition

spree was characterised by incremental improvements to the new Semco, such as the streamlining of

budgeting by paring 400 cost centres down to 50.

Making Unusual Decisions

Semler was in his mid-20s and busy in the effort to integrate recent acquisitions into the old Semco as

he confessed in a medical appointment that he had physically collapsed more than once in his usually

long workdays. Convinced of the threat that he would be retuming frequently to the doctor's should he

not mend his ways, Semler embarked on a delegation initiativ'e so that he could manage his time more

reasonably.

At the same time, Semler felt that something about Semco had to be done as welL The old Semco had

been a traditional, hierarchical company that was almost brought down to its knees by a recession. The

new Semco seemed organised and well disciplined, still in Semler's words "we could not get our

people to perform as we wanted, or to be happy with their jobs" (4). Feeling the company needed

enthusiasm, Semler started to experiment with unusual decisions, such as eliminating the company

dress code and the end-of-day security searches. Next came the revoking of parking privileges for

management, and the elimination of executive dining rooms. Members of management that were used

to the old, traditional Semco found it increasingly difficult to stay.

4

300-153-1

In Semler's own words, "These ideas didn't just come to me. I was testing some of the things I'd learnt

in the rock group, where if the drummer doesn't fee11ike coming to rehearsals you know something's

wrong. You can hassle him as much as you want but the problem remains." (5)

The cultural shift that Semler kicked off gained momentum from 1985 onwards. What started as a

seemingly innocuous string of decisions such as the elimination of parking privileges took a much

larger shape as workers in the Hobart plant became increasingly more responsible for their own work.

Soon they were setting their own production quotas and redesigning the dough mixers they made.

The empowerment that progressively permeated the organisation shocked some supervisors, who felt

their power had been taken away. They would complain to Semler in hallways: "I can't even tell if my

people are arriving on time." (6) Aformer Commercial Director who spoke against the changes noted

that "we lost control of some of the decisions which are [now made] by the employees..... I feel I have

to take the decisions. As an Executive Director you should be responsible for some of the decisions.

But when everyday the workers from the factory come with another proposition - we need this or we

need that- you do not have time to think about the strategy of the company." (7)

By the late 1980's, the unstoppable cultural changes had reached Semco's structure. The old Semco,

which had been a traditionally functional organisation, became the hew Semco with an "amoeba-like"

structure of groups of no more than 10 members. In Semler's words, "I have never met anyone who

works effectively with more than 10 or 12 people at the same time. If you PJIt together a group of 200,

the transparency is lost and you need to put control systems inplace to make sure people are coming in

on time. Then it all becomes a boarding school problem." (8)

At some point in the mid-1980's, three Semco engineers proposed a new kind of work unit. They

wanted to take a small group of people raised in Scmco'sculture and set them free of day-to-day

activities such as production problems, orders and inventory. Instead, they would focus on innovation

of any type, which could include: the creationof new product lines, improvement of manufacturing

processes, or the development of new market strategies.

The so-called Nucleus of Technology Innovation (NTI) was thus started. NTI members would be part

of a totally flat hierarchy with neither bosses nor subordinates. Their performance would be assessed

5

300-153-1

every 6 months by Partners, which would decide whether the NTI members would be allowed 6

additional months of work or not. By the end of their first six months, NTI had 18 projects under way,

and over the next few years they uncorked an array of inventions, changes and refinements. One

particularly curious invention was a scale that weighs fright trains moving at full speed. Further, NTI

compensation and performance would be closely related, as NTI members would be entitled to

royalties emanating from new creations and a share of any savings identified. Semco management

calculated that a Semco engineer that made US$ 25k a year (in 1987 dollars) on average would be paid

anywhere between US$15k and US$85k per year depending on performance.

Next, a company-wide job rotation programme touched every position at Semco - including the CEO-

ship, which would be shared by 6 rotating "Counsellors". This informal board would frequently meet

on day-to-day decisions, while the CEO-ship would be rotated among the Counsellors every 6 months.

Semler gave up the CEO title and became a Counsellor. The Semco hierarchy, which once housed 12

levels, was pared down to only 4. And as the results followed, the Counsellors felt it would be unfair

not to implement a profit-sharing programme that would reach every corner of Semco - including the

factory floors. After a company-wide debate, the Semco Profit-Sharing Programme (SemcoPar) was

designed. Every quarter, it would deliver 23%of each autonomous business unit's profits to the

employees of each individual business unit.

Hand-in-hand with empowerment and transparency came the elimination of unnecessary controls. For

instance, nobody at Semco knows exactly how many people the company employs. Semler explains:

"When we walk through our plants, we rarely even know who works for us: Some of the people in the

. .

factory are full-time employees; some work for us part-time; some work for themselves and supply

Semco with components or services; some work for themselves under contract to outside companies

(even competitors); and some of them work for each other. We could decide to find out which is which

and who is who, but [... ] we think it is all useless information." (9)

Semler is keen to point out that the apparent lack of control systems does not harm efficiency. Quite on

the contrary, "we delivered our last cookie factory with all its 16,000components right on time. One of

our competitors, a company with tight controls and hierarchies, delivered a similar factory to the same

client a year and two months late." (10)

6

300-153-1

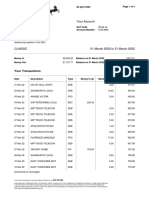

Company-wide transparency means that every single Semco employee, white collar and blue collar

alike, are given a monthly sheet with the their business unit results. When asked whether he could

actually read a P&L, one blue collar employee replied: "Yes, I do understand Semco's P&L. I was given

a crash course some time ago. It was eo-funded by the union." (11)

Regarding any potential collateral effects of transparency, Semler explains that "people warned me

that all sorts of information about our company would get into the wrong hands, that we had to protect

ourselves. It's a waste of time to worry about leaks. First of all, we do not know whose the wrong

hands are. The competition used to be [... ] a mile away, but now it comes from companies [... ] in

Taiwan or in Finland. Second, I've never seen a company overtake another because it had seen its

[quarterly reports] or even the specifications for a valve. Third, we want to be a moving target." (12)

As of whether Semco practices may be a target of employee abuse, Semler points out that "we've had a

few employees take wholesale advantage of our open stockrooms and trusting atmosphere, but we

were lucky enough to find and prosecute them without putting in place a lot of insulting watchdog

procedures for the nine out of ten who are honest. We've seen a few cases of greed when people set

their own salaries too high." (13)

Semco's results in the 1980's were solid. By 1988, Semco's sales had soared to U$35m, almost nine times

of what it had been when Semler took charge in 1980. Productivityalso improved dramatically, as per-

employee sales increased from US$10.8kper head in 1980to US$92kin 1992. When asked about how

has Semco survived in the 1980's, Semler replied "hard work, of course. And good luck - fundamental

to all business success. But most important, I think, were the drastic changes we made in our concept

of management. Without those changes, riot even hard work and good luck could have pulled us

through." (14)

Semco Practices as at 2000

Semco is a company entirely different from the one Ricardo Semler inherited from his father and

Semco-founder two decades ago. A brief overview of Semco as at 2000can be summarised as follows:

7

300-153-1

Strategy:

No "Grand Strategy": Semco does not have a "grand plan". Semler mentions that "I don't know what we

shall be making in 15 years' time, or how we shall be making it - it won't be my decision. But as a

shareholder, I'm more confident in this investment than I would be in a conventional company whose

grand strategy seemed failsafe by today's lights." (15) Further, Semler points out that "I think that

strategic planning and vision are often barriers to success." (16)

NTI's

Associates

Co-ordinators

Partners

Gunsellors

Semco

structure

operations, such as the next year's investment plan;

Structure:

Circular Organisation: Layers of hierarchy of the organisation have been reduced from twelve to four

fluid, concentric circles (see figure 1). Semler is one of six CEO's who are called Counsellors. The

next circle are those in-charge of business units and are called Partners. The third circle are the first-

line supervisors who are called Co-ordinators. The rest are called Associates. Semco is run by

various committees (where the union is represented) which makes all the decisions on strategy and

Figure 1: Semco's structure. Source: "Maoerick!" by Ricardo Semler, ArrowBusiness, London, pages 183-192

Nucleus of Technology Innauation (NTI): Groups, usually engineers, are periodically freed of day-to-

day responsibilities, in order to invent new products, discover how to reduce costs or improve

8

300-153-1

processes and products. They-oftenpopose new strategies or new lines of business. Their

compensation is related to the results of their entrepreneurship;

Satellite Programme: Counsellors, Partners, Co-ordinators and Associates are encouraged to set up

their own businesses to sell to Semco items that used to be done in-house. They can also sell to

competition. To ease the transition, Semco leases out the equipment they need at reasonable rates.

One former Semco employee who now owns and runs a satellite business explains that "we

received technical support and help to physically set up the job shop, but no direct cash infusions"

(17). Interestingly, these satellite businesses borrow not only Semco hardware but also Semco

values. According to [oao Scares, a former Semco employee and union representative who now

runs a successful satellite: "Transparency is most important to our 15 employees, who have access

to the company's books. It is a way of encouraging dedication and loyalty to my company." (18)

When asked whether he was trying to get rid of surplus personnel and old machinery, Semler said

"Some of these machines are actually brand new. As far as the employees go, some of them have an

entrepreneurial flair and will succeed [in their satellites], whereas the ones that do not succeed and

go bankrupt can return the equipment and get back to work with us." (19)

Staffing:

Sticking to Basics: There is no support staff doing dead-end jobs. Everyone sends his or her own fax

and meets their guest. There is no executive dining room or reserved parking space;

"Lostin Space": New recruits are let Idose in Semco for about a year. They have no bosses, no job

descriptions. They are simply asked to spend time in all departments. After about a year, they

negotiate a longer-term involvement with a department;

Reverse Evaluation: Promotions in rank and salary are voted on by those who have worked with the

person concerned. Every six months, a Co-ordinator or Partner is rated by those who have worked

with him. Those who are rated consistently Iow eventually leave the company. (See appendix 1 for

selected questions of the supervisor evaluation tool);

Self-set Pay: The members of Semco themselves decide what their pay will be. They are involved in

salary surveys. Hence, surveys have high credibility. The principle is that employees will think not

only of their welfare but also that of the company and that common sense will prevail. SemIer says

9

300-153-1

that "paying people whatever they want seems a sure route to bankruptcy, but we've done this for

eight years, and we've never performed better (20). When asked about how much he made himself,

Sem1er explained that "my pay varies between US$150k and US$400k per year depending on

circumstances. The decision that the other Counsellors have to make every 6 months is not whether

I make too much or too little, but whether they want to keep me or not for this amount" (21);

Risk Salary: On a voluntary basis, employees (Associates) have joined the risk-salary system where

they take an automatic cut of 25%in pay when business is bad but also get 125%of pay when the

business has had a good year;

Family Silverware: When a newjob opportunity is available, the applicant's characteristics are

graded from 0 to 100. The evaluation criteria are put together by the individuals with whom the

new opening will have the most day-to-day contact. The applicant's score is obtained through

multiple interviews, and then compared against the ideal candidate (score of 100 points) as defined.

If a person in the organisation scores 70, he or she will get the job over an outsider even if the

outsider scored 95, as Semco personnel are familiar with Semco's culture;

Job security: Job security is not offered nor is it asked;

Strikes: Unfortunately, strikes have not beeneliminated yet. Associates cancall a strike anytime.

There is no punishment for going on strike. During a strike in the Hobart plant in the mid 1980's,

the employees found out that they were free to enter the Semco premises during the strike and even

use the cafeteria for meetings. On the other hand, they also found out thatSemco never negotiates

during strikes. Only after the employees are back to work is Semco ready to negotiate.

Systems:

Few rules: There are few rules. There are no rules on travel. There is no internal audit group. The

assumption is that common sense will prevail;

Few Controls: Semco does not control expenses such as travel. Semler explains that "we used to

spend a lot of time discussing about [travel expenses]. Some people stay in 4-star hotels and some

live like spartans. No one checks expenses, so there is no way of knowing. The point is, we don't

care. If we can't trust people with our money and their judgement, we sure as hell shouldn't be

10

300-153-1

sending them overseas to do business in our name." (22) When asked about Semco before Semler's

arrival, one job shop worker said that "1felt very uncertain in those times, with guards checking my

bag at the end of the workday. When I went to the toilet, the supervisor would watch me from the

raised platform and harass me if it took me too long. These days are over now." (23)

Shared Values:

Semler explains that Semco has 3 fundamental values - democracy, profit sharing and information -

thatall work in a complicated circle where each is dependent on the other two (24).

Information

Profit

Sharing

Democracy

~ : : --+-

Figure 2: Semco's shared values

Democracy: This is the cornerstone of the Semco culture. Everyone participates in major decisions.

For example, the purchase of a new plant site or a major acquisition is done via a direct vote of all

members of the organisation. Semler believes that "the main problem afflicting [most] companies is

autocracy. America, Britain and Brazil are all very proud of their democratic values in civic life, but

I have yet to see a democratic workplace. That is the difficult transition that.is going on. We are still

constricted by a system that doesn't allow democracy into business or into the workplace." (25) One

Counsellor explains that Semco's core values are"freedom, trust and commitment" mentioning

that "we were thus able to take the fear out of the organisation" (26);

Information: Information is available to everybody. Nothing is kept secret. Everyone is trained how

to read financial statements. An employee can talk with media without fear of repercussion. Semler

adds that"participation gives people control of their work, profit-sharing gives them a reason to do

it better and information tells them what's working and what isn't." (27)

11

300-153-1

Profit-Sharing (SemcoPar): Periodically, the employees of Semco determine what their profit share

should be (usually 23%in the last several years) and they also decide how to split the profit share;

Style:

The Workplace: Offices have no walls. Only plants separate the workers who are encouraged to

mingle with each other freely. Work is clustered in a way that a complete product, not just a

component, is made;

Workat home: Everyone is encouraged to do at home the work that can be done there; Semler

himself works about three mornings a week at home;

Flexitime: The workers decide on their working hours. Experience has been such that individual

preferences have been subordinated to group schedules;

Memos: Memos must be kept to one page. There are no exceptions.

Skills:

Sabbatical training: By approval of eo-workers, everyone is encouraged to recharge or learn new

skills. One is encouraged to envision what he or she would like to become say five years hence and

then take the initiative to get the necessary training;

Job rotation: On a regular basis, everyone is encouraged to ~ h n g e jobs inSemco, This way, they

learn new skills and there is more than one person ready to take on a job that has been vacated.

Finally, Semler seems to believe Semco is on the right track. In a 1992 survey for instance, 93% of

Associates and Co-ordinators said they are happy to go to work on Monday mornings. Semler believes

that "people go to work because they are looking to do something with their life. I have never met

anyone who goes to work for the money. In the same way I have never met any businessman who is in

business to make money." (28) Semco counsellor [oao Vendramim believes the unique culture is one of

the company's greatest assets, mentioning that "what I like most [about Semco] is the environment of

freedom, absence of fear, encouragement to take risks [and] the opportunity to have a nice feeling of

belonging to something very interesting." (29)

12

300-153-1

In the meantime, Semco has become one of Latin America's fast-growing companies. Semco continues

to grow through partnerships. One of Semco's latest ventures is ERM Brasil, one of Brazil's largest

environmental consulting companies, a joint venture with Environmental Resources Management.

Another example is the partnership with the New-York based consultancy firm Cushman Wakefie1d. In

Brazil, Cushman Wakefield Semco is in the business of real estate asset management.

The latest Semco partnership to date was announced in February 2000. Semco then joint-ventured with

Bidcom, creating Semco Bidcom. The start-up would invest over the next few years in equipment and

software aiming to turn the world-wide-web into a tool for the construction industry. Initially, Semco

Bidcom would rent a virtual platform that allows the design of construction works as well as the on-

line trading of materials and services.

In the early 2000' s, Semco's initiative to pursue growth in industries unrelated to its core businesses is

taking the company once more to new territories. According to Semco counsellor [oao Vendramim,

"my view is that [our] challenge now is to accommodate the culture of our foreign partners with ours-

we have several Joint Ventures - ,and still maintaining the core of our culture and our basic values, in a

globally changing business environment, and the ever increasing need to understand and face

diversity." (30)

After a best-seller book on Semco and the extensive press coveragethat followed, Sem1er joined the

international speakers' circle in the late 1990's and gained a guru-like reputation, sharing the

microphone in the 1997 World Masters of Business Seminar with Lee Iacocca, Norman Schwarzkopf

and Stephen Covey. Regarding the new technology-based economy that emerged in the late 1990's,

SemIer said in the June 2000 Forbes CEO Annual Conference that he was happy to see "the end of the

week-ends" (31), mentioning that the internet and the world-wide-web lead to longer working hours

for most people, now able to work at home over week-ends as welL

Ricardo Sem1er pondered about the future strategy of Semco and how the organisation could become

even more of an unusual workp1ace.

.13

300-153-1

Bibliography

(1) "It's Still Rock & Roll Time To Me - Semco's Chief', Financial Times, 15/5/97 page 18

(2) "City Diary: Semier's Secret", Sunday Telegraph, 12/9/93 page 37

(3) Ricardo Semler: "Maverick!", Arrow Business Books, London 1993, page 65

(4) Ibid., page 65

(5) "It's Still Rock & Roll Time To Me - Semco's Chief', Financial Times, 15/5/97 page 18

(6) Ricardo Semler: "Maverick!", Arrow Business Books, London 1993, page 89

(7) "The Maverick Solution", BBCFor Business video production, 1995

(8) Ibid.

(9) Ricardo Semler: "Why My Former Employees Still Work ForMe", Harvard Business Review, Jan/Feb

1994, page 64

(10) Ricardo Semler: "Why MyFormer Employees Still Work For Me", Harvard Business Review,

Jan/Feb 1994, page 74

(11) "The Maverick Solution", BBCFor Business video production, 1995

(12) Ricardo Semler: "Why MyFormer Employees Still Work ForMe", Harvard Business Review,

Jan/Feb 1994, page 72

(13) Ricardo Semler: "Why My Former Employees Still Work ForMe", Harvard Business Review,

Jan/Feb 1994, page 65

(14) Ricardo Semler: "Managing Without Managers", Harvard Business Review, Sep/Oct 1989, page

77

(15) "The Boyfrom Brazil: Ricardo Semler" by Simon Caulkin.Observer, 17/10/93 page 8

(16) Ricardo Semler: "Why MyFormer Employees Still Work ForMe", HarvardBusiness Review,

[an/Fob 1994, page 64

(17)

(18)

(19)

(20)

(21)

(22)

78

(23)

"The Maverick Solution", BBCFor Business video production, 1995

Ibid.

Ibid.

"How the Maverick Boss Keeps Himself on His Toes" by Robert Heeler, Mail on Sunday, 8/1/95

"The Maverick Solution", BBCFor Business video production,1995

Ricardo Semler: "Managing Without Managers", Harvard Business Review, Sep/Oct 1989, page

"The Maverick Solution", BBCFor Business video production, 1995

14

300-153-1

(24) Ricardo Sem1er: "Managing Without-Managers", Harvard Business Review, Sep/Oct 1989, page

77

(25) "Has Work Reached The End of Line?" by Victor Keegan, The Guardian, 28/9/93 page 2

(26) "The Maverick Solution", BBCFor Business video production, 1995

(27) " A Welcome Breath ofLaisser Faire", Financial Times, 30/10/96 page 11

(28) Ibid.

(29) [oao Vendramim in an e-mail interviewwith Gary Stockport and Femando Chaddad, 21/9/00

(30) Ibid.

(31) "Sem Week-End", by Cesar Ciobbi, Agencia Estado de 5ao Paulo, 17/06/00

15

Appendix 1:Selected Questions of the Supervisor Evaluation Tool

When an employee makes a small mistake, the subject is:

a. Irritated and unwilling to discuss the mistake

b. Irritated but willing to discuss it

c. Realises the mistake and discusses it in a constructive manner

d. Ignores the mistake and only pays attention to more important matters

The subject reacts to criticism:

a. Poorly, ignoring it

b. Poorly, rejecting it

c. Reasonably well

d. Well, accepting it

The subject is:

a. Constantly tense

b. Usually tense, but relaxed on occasion

c. Usually relaxed, but tense on occasion

d. Constantly relaxed

When the subject's department achieves a high level of productivity, the subject usually:

a. Takes credits for others' success

b. Gives the credit to those who did the work

c. Gives credit to the team as a whole

The subject is:

a. A weak leader, unable to motivate the team

b. A weak leader, but able to motivate the team

c. A strong leader, but unable to motivate the team

d. A strong leader, but able to motivate the team

During a crisis, the subject

a. Disrupts the team's unity

b. Does not affect the team's unity

c. Helps the group stick together

The subject is

a. Not very creative and resists new ideas

b. Too creative and change-oriented, disturbing the atmosphere

c. Adequately creative and change-oriented

16

300-153-1

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Leveraged Buy Out Deal of TataDocument7 pagesThe Leveraged Buy Out Deal of TataNeha ChouhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Statement 2022 3Document4 pagesStatement 2022 3Dulo WegnerPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study Richard Semler at SEMCODocument9 pagesCase Study Richard Semler at SEMCOResty Febrianty100% (1)

- Land Form No. 1-71.regulationsDocument211 pagesLand Form No. 1-71.regulationsSha Riz80% (61)

- Ben & JerryDocument11 pagesBen & Jerryfatin hidayuPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study Distribution Channels KomatsuDocument5 pagesCase Study Distribution Channels KomatsuRahul Rajasekhar MenonPas encore d'évaluation

- Kentucky Fried Chicken in JapanDocument3 pagesKentucky Fried Chicken in Japanezeasor arinzePas encore d'évaluation

- Anne Mulcahy - Leading Xerox Through The Perfect StormDocument18 pagesAnne Mulcahy - Leading Xerox Through The Perfect Stormabhi.slch6853Pas encore d'évaluation

- General Electric Medical Systems, 2002Document10 pagesGeneral Electric Medical Systems, 2002Jyotsna GautamPas encore d'évaluation

- When Workers Rate The BossDocument3 pagesWhen Workers Rate The BossSHIVANGI MAHAJAN PGP 2021-23 BatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Semco Unique Self OrganziationDocument12 pagesSemco Unique Self OrganziationAaron Ross100% (6)

- Semco Case StudyDocument10 pagesSemco Case StudySonal Srivastava100% (2)

- Affidavit of Non ImprovementDocument1 pageAffidavit of Non Improvementnagelyn mejiaPas encore d'évaluation

- SEMCO - Employee-Powered Leadership - Brazil - 2005Document14 pagesSEMCO - Employee-Powered Leadership - Brazil - 2005Avinash GadalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Microsoft and Sendit CaseDocument6 pagesMicrosoft and Sendit CaseCamilla CenciPas encore d'évaluation

- Ricardo Semler & Semco, Thunderbird ResearchDocument12 pagesRicardo Semler & Semco, Thunderbird ResearchRomuald KamtoPas encore d'évaluation

- Internal and External CommunicationDocument18 pagesInternal and External CommunicationioeuserPas encore d'évaluation

- Value Chain AnalysisDocument6 pagesValue Chain Analysisamolk_87Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ricardo Semler - Maverick - SummaryDocument9 pagesRicardo Semler - Maverick - SummaryHasanErkelPas encore d'évaluation

- Eurocode 0 Structural Design Eurocode 1 Structures:: Basis Of: Actions OnDocument3 pagesEurocode 0 Structural Design Eurocode 1 Structures:: Basis Of: Actions OnSAN RAKSAPas encore d'évaluation

- EVA and Compensation Management at TCSDocument9 pagesEVA and Compensation Management at TCSioeuser100% (1)

- Global Mobile Corporation: Case AnalysisDocument7 pagesGlobal Mobile Corporation: Case AnalysisGayatri KapoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Maverick (Review and Analysis of Semler's Book)D'EverandMaverick (Review and Analysis of Semler's Book)Pas encore d'évaluation

- AminaDocument2 pagesAminaKendrick Edwardo100% (1)

- Group 1 Presentation - Mavrick - Ricardo SemlerDocument33 pagesGroup 1 Presentation - Mavrick - Ricardo SemlerLombe Mutono100% (7)

- Ricardo Semler and Semco S.A.Document10 pagesRicardo Semler and Semco S.A.Sarah RuenPas encore d'évaluation

- Semco Case StudyDocument12 pagesSemco Case StudyArittraKarPas encore d'évaluation

- SEMCO - A Maverick OrganisationDocument8 pagesSEMCO - A Maverick Organisationrakeshb11Pas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study of SemcoDocument13 pagesCase Study of SemcoVinesh MoilyPas encore d'évaluation

- RicardoDocument5 pagesRicardosaddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study #3 FormattedDocument7 pagesCase Study #3 FormattedHector Miramontes0% (1)

- Build Satya Nadella FINALDocument27 pagesBuild Satya Nadella FINALQuoc Tuan LePas encore d'évaluation

- Semco BrazilDocument17 pagesSemco BrazilAniruddhShastree100% (1)

- OD ExerciseDocument15 pagesOD ExerciseNavinPas encore d'évaluation

- GE AnalysisDocument14 pagesGE Analysisaby0% (1)

- Ricardo Semler - Group 3Document3 pagesRicardo Semler - Group 3Arpit MalviyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gillette Case Submission Group 1 Section BDocument14 pagesGillette Case Submission Group 1 Section BShruti Pandey100% (2)

- SemcoDocument29 pagesSemcocompangelPas encore d'évaluation

- Ricardo Semler: Halimatu Sadiya Ali Gina Von HardenbergDocument19 pagesRicardo Semler: Halimatu Sadiya Ali Gina Von HardenbergHalimatu Sadiya AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Case 1 AnswersDocument3 pagesCase 1 AnswersMuhammad SulemanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases For Analysis 2: The Paradoxical Twins: Acme and Omega ElectronicsDocument5 pagesCases For Analysis 2: The Paradoxical Twins: Acme and Omega Electronicsmohamed alaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hausser Food Products CompanyDocument1 pageHausser Food Products CompanyOlojo Oloyomi MichaelPas encore d'évaluation

- When Teams Can't DecideDocument12 pagesWhen Teams Can't DecideanassaleemPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment On OBDocument24 pagesAssignment On OBHarshit MarooPas encore d'évaluation

- Maria SharapovaDocument26 pagesMaria SharapovaSwapnil ChonkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 7 - Oscar MayerDocument17 pagesGroup 7 - Oscar Mayershagun100% (1)

- Statistics Case - Shell - Sampling (Mohamed Hussain)Document1 pageStatistics Case - Shell - Sampling (Mohamed Hussain)Dhona ?100% (1)

- Disney PixarDocument9 pagesDisney PixarrockysanjitPas encore d'évaluation

- Putting People First For Org Success - Exec SummaryDocument1 pagePutting People First For Org Success - Exec SummaryRaúl MaldonadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Merger & AcquisitionDocument29 pagesMerger & AcquisitionHamizar HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- Building Effective One On One Work Relationship 20110818Document1 pageBuilding Effective One On One Work Relationship 20110818Meidi ImanullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Haier Group: OEC ManagementDocument10 pagesHaier Group: OEC ManagementNitinchandan KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- ATH TechnologiesDocument3 pagesATH TechnologiesAnurag PGXPM15Pas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Edmondson & Smith (2006) Too Hot To Handle How To Manage Relationship Conflict PDFDocument28 pages5 Edmondson & Smith (2006) Too Hot To Handle How To Manage Relationship Conflict PDFNadia Farahiya RachmadiniPas encore d'évaluation

- TycoDocument10 pagesTycoAnna0082Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kapur - Sports in Your PocketDocument4 pagesKapur - Sports in Your Pocketak1147Pas encore d'évaluation

- Closing The Gender Pay GapDocument4 pagesClosing The Gender Pay Gapapi-530290964Pas encore d'évaluation

- AssignmentDocument9 pagesAssignmentAnjana CramerPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Management-II Case Analysis: Eureka Forbes LTD: Managing The Selling Efforts (A)Document4 pagesMarketing Management-II Case Analysis: Eureka Forbes LTD: Managing The Selling Efforts (A)Kalai VaniPas encore d'évaluation

- This Study Resource Was: Relationship With Richard PatricofDocument1 pageThis Study Resource Was: Relationship With Richard PatricofCourse HeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Paradoxical TwinsDocument4 pagesParadoxical TwinsCarolina ArregocesPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational Behaviour Book SummaryDocument71 pagesOrganizational Behaviour Book SummaryEhab Mesallum100% (12)

- Ricardo Semler & Semco, Thunder BirdDocument12 pagesRicardo Semler & Semco, Thunder Birdsahin04Pas encore d'évaluation

- Caso de Estudio Ricardo SemlerDocument12 pagesCaso de Estudio Ricardo SemlerJhon MaykolPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson From SEMCODocument5 pagesLesson From SEMCONoman QureshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Semco Case Study SmsDocument25 pagesSemco Case Study SmsSahal T YousephPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment (Social Research and Case Analysis) : Critical Appreciation Paper (Reaction Paper)Document2 pagesAssignment (Social Research and Case Analysis) : Critical Appreciation Paper (Reaction Paper)himanoj1982Pas encore d'évaluation

- Paradeep DFRDocument22 pagesParadeep DFRioeuserPas encore d'évaluation

- Ommune IT SolutionsDocument21 pagesOmmune IT SolutionsioeuserPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study TrainingDocument5 pagesCase Study Trainingapnamanish99886Pas encore d'évaluation

- RFP For ATM/BRANCH Connectivity Using VSAT/CDMA/RF/FWT: Punjab National BankDocument23 pagesRFP For ATM/BRANCH Connectivity Using VSAT/CDMA/RF/FWT: Punjab National BankioeuserPas encore d'évaluation

- 381-Article Text-1337-1-10-20171221Document7 pages381-Article Text-1337-1-10-20171221Fitri ElitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Acct Statement - XX3873 - 24082023Document18 pagesAcct Statement - XX3873 - 24082023riddhi .brainlyPas encore d'évaluation

- 16 Answers PDFDocument57 pages16 Answers PDFKate ProductionsPas encore d'évaluation

- Discuss The Contemporary Approaches To Management - AssignmentDocument6 pagesDiscuss The Contemporary Approaches To Management - AssignmentPanashe GoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Social ScienceDocument300 pagesSocial Sciencepriyaluck885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rotolok Blowing Seal Valve AMD v3Document4 pagesRotolok Blowing Seal Valve AMD v3wijaya adidarmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mason Isolation MountsDocument1 pageMason Isolation MountsarunjacobnPas encore d'évaluation

- Longmont Re-Roofing GuidelinesDocument4 pagesLongmont Re-Roofing GuidelinesAllen WilburPas encore d'évaluation

- Official Response From Suresh KalmadiDocument2 pagesOfficial Response From Suresh KalmadiNDTVPas encore d'évaluation

- Hotel InvoiceDocument1 pageHotel InvoiceAmri HakimPas encore d'évaluation

- Home Economics LiteracyDocument3 pagesHome Economics LiteracyLouchelle MacasasaPas encore d'évaluation

- Panel DiscussionDocument2 pagesPanel DiscussionjenPas encore d'évaluation

- PNB Foreclosed Properties PPSB Cabanatuan 3.21.13 FlyerDocument2 pagesPNB Foreclosed Properties PPSB Cabanatuan 3.21.13 FlyerAngelo AndalPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On International Trade FinanceDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On International Trade Financeafdtsdece100% (1)

- Bangladesh Telecommunications Company Limited (BTCL) Duplicate Bill (Single Month)Document1 pageBangladesh Telecommunications Company Limited (BTCL) Duplicate Bill (Single Month)Akbar CottonPas encore d'évaluation

- Technical Manual. Level & Pressure Transmitter TYPE PL3700Document30 pagesTechnical Manual. Level & Pressure Transmitter TYPE PL3700stéphane pervesPas encore d'évaluation

- National Institute of Textile Engineering & Research (Niter)Document128 pagesNational Institute of Textile Engineering & Research (Niter)Nirnoy ChowdhuryPas encore d'évaluation

- Bus Math-Module 6.5 Test of of Significant DifferencesDocument131 pagesBus Math-Module 6.5 Test of of Significant Differencesaibee patatagPas encore d'évaluation

- ECON Inflation, Spending, and WagesDocument2 pagesECON Inflation, Spending, and WagesRaylin JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Procter & Gamble Company: Examining Product DecisionsDocument8 pagesProcter & Gamble Company: Examining Product Decisionsshivam kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- American March Pump 460 ODSDocument24 pagesAmerican March Pump 460 ODSjuan davidPas encore d'évaluation

- 5) The Economic Theory of RegulationDocument23 pages5) The Economic Theory of RegulationBrian HuPas encore d'évaluation

- CV Derry 2022Document1 pageCV Derry 2022mks iainsagPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020 Ba I Reading ListDocument14 pages2020 Ba I Reading ListDaisy NPas encore d'évaluation

- Daiwik Spandana BrochureDocument15 pagesDaiwik Spandana BrochureRitvikLalithPas encore d'évaluation