Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Remembering Sylhet A Dasgupta

Transféré par

hujsed0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

106 vues5 pagesRemembering Sylhet a Dasgupta

Titre original

Remembering Sylhet a Dasgupta

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentRemembering Sylhet a Dasgupta

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

106 vues5 pagesRemembering Sylhet A Dasgupta

Transféré par

hujsedRemembering Sylhet a Dasgupta

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 5

COMMENTARY

august 2, 2008 EPW Economic & Political Weekly

18

anarchist movements and anti-globalisation

movements are also now added to the list

of terrorisms. One agency in the US even

once included Indias security agency,

the RAW in the list. Every year the list is

expanding. At present, ofcially designated

terrorist groups might be around 800 at

the global level; however, if we add non-

designated groups, the numbers might

cross 1,000.

Jehad has been linked to terrorism in

another context: that of globalisation. The

jehad against western symbolism,

hegemony in culture, power and against

western lifestyle has been conated with

terrorism by many. This jehad is however

a struggle against hegemony of another

culture and has existed before in history,

particularly in the Indian context. For

example, the Muslim sea traders were sup-

ported in their efforts to oppose Portuguese

hegemony through a jehad by the Zamorins

of Calicut. Kunhalis belonging to coastal

Kerala including Calicut, Malabar and

Kochi had also opposed Portuguese hege-

mony [Makdum 2008]. Another example

is that of the 1857 revolt (as revealed by

William Darlymples latest book on The

Last Moghul). Even colonialists of today

regard the struggle against western hegem-

ony a form of jehad (Clash of civilisations

according to Samuel P Huntington).

It is but obvious that the Darul Uloom

Deoband schools decision to denounce

all forms of terrorism must be appreci-

ated. At the same time, one must make a

contrast between terrorism and the jehad

against western hegemony (which is a

constructive one). This jehad should

o rient itself to recognise and protect the

rights of women, dalit Muslims and the

poor, through the process of opposing

western hegemony which has manifested

through the processes of globalisation

and capitalism.

References

Darul Uloom, Deoband (2008): Declaration: All India

Anti-Terrorism Conference, http://darululoom-

deoband.com/english/index.htm

Makdum, Shaykh Zainuddin (2008): Tuhfat Al-

Mujahidin, Other Books, Calicut.

This article is part of a larger study Where Is

Sylhet? Hindu and Muslim Voices from a

Forgotten Story of Indias Partition that has

been supported by a postdoctoral grant from

SEPHIS, International Institute of Social

History, The Netherlands. The author thanks

Khaleda Sultana Ahmed for her valuable

eldwork support for this project.

Anindita Dasgupta (historienne@yahoo.com)

teaches history at a Malaysian University, and is

currently a recipient of SEPHIS postdoctoral

grant to write an oral history of Indian Sylhetis.

Remembering Sylhet:

A Forgotten Story of Indias

1947 Partition

ANINDITA DASGUPTA

Studies of Indias Partition have

been focused on the cases of

Punjab and Bengal, but very

few have been based on the site

of partition in colonial Assam,

Sylhet. Urgent attention

is required to record the

historiography of partition in

Sylhet as many of those who had

experienced the phase of partition

are more than 80 years old now.

D

espite major methodological

strides

1

made in recent years, most

studies of Indias 1947 Partition

continue to remain focused on the two

better-known cases of Punjab and Bengal.

Remarkably little is known about other

partition sites the Sylhet district of colo-

nial Assam, for instance which was

ceded to (East) Pakistan following the

outcome of a referendum held on July 6

and 7, 1947 according to Mountbattens

partition plan of June 3, 1947. Besides a

small Hindu pocket consisting of Ratabari,

Patherkandi, Hailakandi and half of Kar-

imganj thana, the rest of the district left

Assam/India to join East Pakistan. Sixty

years afterwards, the stories of such lesser

known partition sites face the danger of

being overlooked and forgotten by what

may be called mainstream partition his-

toriography unless documented without

delay. Because oral history uses spoken

sources, even in the absence of written

documentation oral historians are able to

document the histories of groups which

have long been out of historical focus.

Given that the people who can remember

and retell the story of the 1947 Sylhet par-

tition, are more than 80 years old now,

this task assumes even greater urgency.

Eastward towards Assam

Of late, historians in south Asia have been

using non-traditional sources like memo-

ries, folk history and popular ction to

shed new light on the experiences of

o rdinary people whose lives were thrown

into turmoil by the 1947 Partition. Their

studies have helped esh out the hetero-

geneity and the unevenness in the expe-

rience of Partition and generated a de-

bate among academics. But in spite of

vast and rich research, this new history

still falls short of providing a wide-

ranging view of the local nuances of

P artition of India due to its near exclusive

focus on Punjab and Bengal. Against this

background, it may be interesting to turn

the lens further east and north of Bengal,

to look at a third site of partition, the

d istrict of Sylhet in the erstwhile colonial

province of Assam.

Assam was little known in British India

except for its tea production but which

eventually became included in Jinnahs

demand for a six-province Pakistan.

A Background

Sylhet, a Bengali-speaking district histori-

cally a part of East Bengal, was joined

with its Assamese-speaking neighbour

Assam in 1874 by the British who wanted

COMMENTARY

Economic & Political Weekly EPW august 2, 2008

19

!"#!$"!"%&!&'&( )* $#+$",(#%&'#-

./0123/4/25 "56/07 %1589/ :;:<<=

Advertisement No. 5/2008

AWARD OF FELLOWSHIPS

1. Applications for award of Fellowships for advanced research in the following areas are invited:

a. SociaI, PoIiticaI and Economic PhiIosophy;

b. Comparative Indian Literature (incIuding Ancient, MedievaI, Modern FoIk and TribaI);

c. Comparative Studies in PhiIosophy and ReIigion;

d. Comparative Studies in History (incIuding Historiography and PhiIosophy of History);

e. Education, CuIture, Arts incIuding performing Arts and Crafts;

f. FundamentaI Concepts and ProbIems of Logic and Mathematics;

g. FundamentaI Concepts and ProbIems of NaturaI and Life Sciences;

h. Studies in Environment;

i. Indian CiviIization in the context of Asian Neighbours; and

j. ProbIems of Contemporary India in the context of NationaI Integration and Nation-buiIding.

2. Since the nstitute is committed to advanced study, proposals involving empirical work with data collection and fieldwork

would not be considered.

3. Applications from scholars working in, and on, the North Eastern region are encouraged.

4. Scholars belonging to the weaker section of society would be given preference.

5. The nstitute shall publish the monographs of the Fellows on completion of their term.

6. The prescribed application form and details of the Fellowship grants payable to the Fellows are available on the website of

the nstitute www.iias.org and can also be obtained from the nstitute by sending a self-addressed envelop (5x11") with

postage stamp of Rs. 10 affixed. The application on the prescribed form may be sent to the Secretary, Indian Institute of

Advanced Study, ShimIa 171005. Applications can also be made on line at www.iias.org.

7. The term of Fellowship would initially be for a period of one year, extendable further, but in no case will it extend beyond two

years.

8. Fellows would be expected to remain in residence from mid March to mid December. Their stay at the nstitute during the

remaining months would be optional. They may proceed on Study Tours during this period.

9. The nstitute provides fully furnished rent free accommodation to Fellows within the campus. n addition, scholars will be

provided a personal fully furnished study (which may be on sharing basis) with computer and nternet facilities. The Fellows

will not be entitled for any House Rent Allowance (HRA).

10. The Fellows will be provided with free stationary. n addition, they would have access to nstitute vehicles for local travel on

payment of nominal charges.

11. On matters of health, Fellows are entitled for free medical treatment at the dispensary of the nstitute.

12. t is mandatory for in-service candidates to apply through proper channel.

TheFellowshipSelectionCommitteeis likelytomeet inthesecondweek of September 2008. Thoseinterestedcanget further detailsfrom

the PubIic ReIations Officer of the nstitute. He is available on e-mail at proiias@gmail.com

to make the latter province economically

viable and self-sustaining. For several

years afterwards, the Hindus of Sylhet

demanded for a return to the more

advanced Bengal, whereas the Muslims

of Sylhet by and large preferred to remain

in Assam where its leaders, along with

the Assamese Muslims, found a more

powerful political voice than they would

have had if they returned to a Muslim-

majority East Bengal. The indigenous

Assamese too supported the separation

of Sylhet from Assam for the entire

period from 1874-1947 as the Sylhetis or

inhabitants of Sylhet with their earlier

access to English education were seen as

competitors for jobs, and as exercising a

cultural hegemony over an incipient

Assamese middle class trying to come

into its own under the aegis of British

colonialism since 1826.

Ironically, when the opportunity for a

return to East Bengal (later East Pakistan)

came in 1947, the Sylheti Hindus defended

their right to remain in Assam/India while

many Sylheti Muslims wanted to separate.

When the referendum was held on July 6

and 7, the outcome was by and large

c onsistent with the demographic com-

position of the district where Muslims

had a numerical edge: 56.6 per cent of

Sylhetis voted for joining East Pakistan

and 43.3 per cent voted for remaining in

Assam/India. Following this outcome,

most of the Sylhet district was ceded to

East Pakistan.

Over the next few years, large numbers

of Sylheti Hindus from the ceded parts

of Sylhet district began to relocate to the

Indian north-east, particularly to southern

Assam, where they had established con-

siderable economic and social networks in

the period 1874-1947.

2

Over time there

emerged a de-territorialised Sylheti iden-

tity in Assam/India, as Sylhetis formed

pockets of minority groups despite con-

siderable indigenous opposition to refugee

settlement giving rise to powerful

i dentity politics in post-colonial years. In

spite of being challenged by assimilative

drives from time to time, festering citizen-

ship issues, and the loss of a rm territori-

alised identity, Sylhet and Sylheti-ness

continue to be recreated in many social,

cultural and political forms in different

parts of north-east India, particularly

Assam, which remains today home to a

large Sylheti settlement.

The Indian Sylheti Identity

The 1947 Sylhet referendum and partition

was the dening moment of the (Indian)

Sylheti identity for two reasons.

First, it marked the fracture of the

Sylheti identity into at least two: the East

Pakistani (since 1971, Bangladeshi) and

the Indian Sylheti. The Bangladeshi

S ylheti identity is commonly associated

with Muslims from the Sylhet division of

modern Bangladesh who claim to be

e thnically and culturally separate from

other Bengalis in Bangladesh. The Indian

COMMENTARY

august 2, 2008 EPW Economic & Political Weekly

20

Sylheti identity, on the other hand, is

l ittle understood or recognised outside

north-east India and it is associated

p rimarily with the Hindus from both the

ceded and the retained parts of erstwhile

Sylhet district and who sometimes claim,

ironically, to be a part of the greater

B engali diaspora (probashi bangali) in

post-colonial India.

It was also the beginning of a minori-

tised and de-territorialised Sylheti iden-

tity in post-independence India. The parti-

tion of Sylhet drastically reduced the

number of Bengali-speaking Sylhetis in

Assam, compared to the colonial times

when to the population of Sylhet one

adds the number of Bengalis who immi-

grated to Assam, there were more Ben-

galis in Assam than Assamese [Baruah

1990]. Secondly, even the ofcial name of

Sylhet was retained by East Pakistan/

Bangladesh. The small Hindu pocket that

remained with Assam/India was sub-

sumed within Assams Cachar district and

thereafter Sylhet altogether disappeared

from the map of independent India. While

Indian Sylhetis gradually learnt to asso-

ciate themselves territorially with

K arimganj, Shillong or Silchar, or

simply Assam, their imagined identity

remained tied to Sylhet in many different

ways. Thus, many little Sylhets, standing

un certainly bet ween a real and imagined

identity, were recreated in different parts

of north-east India over time.

Sylhet Partition Nuances

The Sylhet partition story has its own

nuances: Firstly, none of the academic

or popular works contain any direct

r eferences to major outbreaks of com-

munal violence in Sylhet during or after

the r eferendum. This is in striking con-

trast with the literature on Punjab and

Bengal partitions, which are replete

with accounts of communal violence,

betrayals, forced migration, rape,

a bduction, etc. There are intermittent

references to communal tension, fears,

petty criminal activities and rumours,

but none of the Hindu-Muslim riots/

clashes that one has come to associate

with the Punjab and Bengal cases. Admit-

tedly, some studies of the Bengal parti-

tion also point out that some of the

migration was caused by a perception of,

rather than actual, violence. Others sug-

gest that some of it was caused by eco-

nomic dis locations that made older pat-

terns of li velihood untenable, yet refer-

ences to sporadic violence in any such

study are inevitable. In contrast, the

absence of any direct mention of commu-

nal violence in Sylhet makes it an inter-

esting topic for future research.

Secondly, a signicant number of the

Sylhetis who migrated to Assam/India

soon after the referendum were excep-

tions to the general image people carried

about Indias Partition in 1947. They were

English-educated optees

3

or govern-

ment personnel who were given the

COMMENTARY

Economic & Political Weekly EPW august 2, 2008

21

opportunity to opt for transferring their

service either to India or Pakistan at the

time of Partition. This is a category of Par-

tition migrants that has not yet been

extensively explored by historians.

Thirdly, while Punjab and Bengal were

divided on the basis of religion, the Sylhet

referendum was a vote not on one, but on

two concentric issues of the reorganisa-

tion of India on a communal basis and of

Assam on a linguistic basis. The second

issue, writes Sujit Chaudhuri had its

origins in what can be called the long-

cherished quest of the Assamese carving

out a homogeneous province for them-

selves.

4

The Assam branch of Indian

National Congress was not totally opposed

to handing Sylhet over to East Pakistan as

a means of settling the old demand of

the indigenous Assamese to separate the

latter district from Assam.

5

Fourthly, unlike Punjab, and to a lesser

extent Bengal, there appears to a wide gap

between the ofcial and personal histories

of Sylhetis. While Sylhet is recreated and

relived in different ways in north-east

India, Partition history remains surpris-

ingly silent on this topic. A purely aca-

demic exercise of looking up the term Syl-

het in some of the more authoritative Par-

tition studies did not provide much infor-

mation other than what might go into the

writing of a footnote or two. Therefore,

one may say that Indian Sylhetis have no

history, only memories that are passed

down by family elders in the connes of

private spaces giving rise to a narrative of

immediacy and intimacy with Sylhet, that

the older generation lived with and trans-

mitted to the younger generation [Bhatta-

charjee 2006, p 156].

An Imagined Sylhet

Contemporary Sylheti identity has been

constructed through a reclaiming of Syl-

hetiness via folk songs, popular culture,

historical and social narratives, writes

Sukalpa Bhattacharjee [Bhattacharjee

2006, p 163]. Parents of marriageable

Indian girls continue to claim on

m atrimonial web sites that we follow a

traditional lifestyle basically of the value

of Sylhet.

6

Some of them go so far as to

claim that our native place is Sylhet.

7

A yearning for the lost homeland is also

discerned in the storytelling within

S ylheti families (my grandfather) told

me stories of our native place, Sylhet

writes a Sylheti blogger in cyberspace.

Of his childhood there, of the fresh air

and plentiful sh in Surma river. He told

me about books and food and politics.

He told me about the time Gandhi and

Nehru visited Sylhet. There was a

t winkle in his eyes as he described

S ubhash Chandra Boses visit to our native

home in Sylhet.

8

This nostalgia or shadowy memory of

the imagined homeland of Sylhet is also

discerned in much of Amit Chaudhuris

writings, where memories of Sylhet, the

lost homeland of his mother, are repeat-

edly evoked. In A Strange and Sublime

Address, Shonamama recalls his own

childhood in Sylhet when India was

one big piece and the British ruled us,

which was followed by a move to Shillong

with its mountains and waterfalls

[Chaudhuri 2001, p 53]. In Freedom Song,

Mini remembers her childhood in Puran

Lane in Sylhet in pre-Partition days. The

votes were counted after the referendum

writes Chaudhuri, their country was

goneafter two months they packed their

things and took a train to Guwahati and

then a bus to Shillong [Chaudhuri

2001, p 380]. Again, in an evocative arti-

cle titled At the Edge of the Clouds,

Chaudhuri writes that Shillong was the

town to which my mother and her fam-

ily moved, just before Sylhet, rst part of

Bengal, then Assam, was lost to Pakistan

with the referendum.

But this is not the only way in which

Sylhet is continuously remembered and

recreated in contemporary times. Sujit

Chaudhuri argues that had there been

no Partition, there would not have been

any foreigner issue in Assam.

9

He goes

on to say that the foreigner issue,

p rojected as a core question associated

with the survival of the Assamese nation-

ality has drawn its entire rationale from

Partition. Sanjib Baruah too points out

that the separation of Sylhet did not

bring the tensions between Bengalis

and Assamese to an end [Baruah 1990,

p 43]. Thus the legacy of the past con-

tinued to lurk behind the third genera-

tion locally-born children of Sylhetis

though in recent years much recon-

ciliation has been achieved. Yet, a sense

of rootlessness sometimes persists, as

Deb summarises the identity crisis of

the S ylhetis in g eneral in the following

words:

They were dened not by what they were

that was uncertain but by what they were

not. They were Indians because they were

not Bangladeshis, Hindus because they were

not Muslims, Bengalis because they were not

Assamese. They clung to their language

ercely, and yet they were not really Bengali,

because they spoke a dialect that aroused

only amusement and derision in the real

centre of Bengali culture and identity, in

Calcutta.

Thus, while Sylhet lives in innumera-

ble ways in the daily lives of thousands of

Indians, it is remarkable that a serious

effort at writing its history has yet to be

made. An article on the internet spells

out the Sylheti paradox of remembering

and forgetting its own history in these

words:

The greatest paradox is that we being such a

home-loving community, such rooted to our

soil, such grounded with the ethos of the

place but such deep, such unbelievable for-

getfulness. Such a great lapse of memory,

such wonderful epilepsy cannot be explained

unless we take into consideration the fact

this forgetfulness might have been one of

the strongest factors of our survival, physi-

cally as well as culturally, it evades all

explanations. None of our literature, none

of our later stories speak about this cul-

tural discontinuity and this silence, this

Open Review

Several international journals are moving

away f rom cl osed "Peer Revi ew" of

research papers, towards an "Open Review"

process. In open reviews anyone can com-

ment on a paper submitted for publication.

This will increase transparency in reviews

as well as enhance participation and

involvement of the research community.

EPW occasionally posts a submission on its

web site and invites comments. Visitors to

the EPW web site and readers of the journal

are encouraged to offer detailed comments.

EPW will discuss the comments with the

author and a revised version will be processed

for publication.

Please visit the Open Review section on

our web site (www.epw.in) to read and

comment on the paper currently submitted

for Open Review.

COMMENTARY

august 2, 2008 EPW Economic & Political Weekly

22

inexplicable silence may be more resonat-

ing than a lingering sadness, orchestrated

in prose, poetry or music.

10

In Conclusion

Sixty years afterwards, such lesser known

stories face the danger of being forgotten

by mainstream Partition historiography.

The custodians of Sylheti history or, the

eyewitnesses of the Sylhet partition are,

on an average, more than 80 years old

now. Their accounts need to be urgently

documented if one is to come close to a

nuanced understanding of Indias Parti-

tion. In the absence of professional histori-

cal research, Sylheti narratives continue

to construct their own heroes and villains

within the popular realm that may be at

variance with what might hold sway in

academic circles. Many Sylheti eyewit-

nesses themselves expressed the need for

objective historical research to this

researcher, who was often met with apolo-

getic statements like I am not a historian,

but I will tell you what I remember In

the absence of historians, one was advised

to speak with retired Assam government

ofcers from the 1940s and 1950s who

would be able to tell the real story

because they were there on the ground.

Some of the eyewitnesses remember

h azily or choose not to discuss the issue at

all. Many others have passed away, or

have relocated to different parts of India

and abroad to live with their children in

the twilight years of their lives. If a his-

tory of Sylhetis is not documented

urgently, no one will ever know what

really happened in the 1947 Sylhet refer-

endum and partition.

Notes

1 This paper is part of an ongoing larger study.

Therefore, only a few of the ideas developed by

the researcher have been presented here.

2 There is evidence of smaller numbers of Muslims

who migrated to East Pakistan from Assam.

3 Exchange of certain categories of state person-

nel between Pakistan and India was organised

by allowing them to opt for a position in the

other state. These optees, who arrived at the

time of Partition, took the place of counterparts

who travelled the other way. They took charge of

tasks at all levels and in all branches of govern-

ment. Other displaced people joined the state on

an individual basis. The inuence of these new-

comers on state formation and state policies in

the three countries has, to our knowledge, never

been studied, let alone compared http://www.

idpad.org/docs/Vol.%20I%20%20No.%201%20

January-June%202003.pdf accessed on 15/6/

2007.

4 S Chaudhuri, A God-sent Opportunity?, http://

www.india-seminar.com/2002/510/510%20sujit

%20chaudhuri.htm (2002) accessed on 15/

2/2008. Paraphrased by author.

5 Lord Wavell, the viceroy, wrote in his journal as

early as April 1946, that Gopinath Bordoloi, the

Congress Premier of Assam, gave the Cabinet

Mission to understand that Assam would be

quite prepared to hand over Sylhet to Eastern

Bengal (Wavell, the Viceroys Journal, No 21,

April 1, 1946, p 234, quoted from Amalendu

Guha, Planter-Raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle

and Electoral Politics in Assam 1826-1947, New

Delhi, Peoples Publishing House (1977), p 319.)

6 bmser.telugumatrimony.com/cgi-bin/viewpro-

le.php?id=B417467 accessed on 20/5/2007.

7 bmser.bharatmatrimony.com/cgi-bin/viewpro-

le.php?id=B258048 accessed on 20/5/2007.

8 http://209.85.175.104/search?q=cache:vGHosk

zOAQEJ:chaksville.blogspot.com/2007/09/of-

dadu-thakuma-and-b-52-bombers.html+our+n

ative+place+is+sylhet&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1

&gl=my accessed on 16/5/2008

9 Chaudhuri (2002), op cit.

10 http://personal.vsnl.com/syhlleti/para1.htm

accessed on 20/5/2007.

References

Chaudhuri, Amit (2001): Three Novels, Picador,

London.

Bhattacharjee, S (2006): Sylheti Narratives: Memory

to Identity in S Bhattacharjee and R Dev (eds),

Ethno-narratives: Identity and Experience in

North-East India, Anshah Publishing House,

New Delhi, p 156.

Baruah, S (1990): India against Itself: Assam and the

Politics of Nationality, University of Pennsylvania

Press, Philadelphia, p 40.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Indian History Research PaperDocument5 pagesIndian History Research Papercaq5kzrg100% (1)

- Vietnam National UniversityDocument34 pagesVietnam National University2156110198Pas encore d'évaluation

- Yen Ching HwangDocument30 pagesYen Ching HwangShazwan Mokhtar100% (1)

- Unifying Themes in British India's History from 1757-1857Document32 pagesUnifying Themes in British India's History from 1757-1857ThaísPas encore d'évaluation

- Himalayan Anthropology-The Indo-Tibetan InterfaceDocument581 pagesHimalayan Anthropology-The Indo-Tibetan InterfaceTim100% (1)

- Southeast Asia Research PaperDocument6 pagesSoutheast Asia Research Papertijenekav1j3100% (1)

- Some Problems in The Ancient History of The Hinduized States of South-East AsiaDocument15 pagesSome Problems in The Ancient History of The Hinduized States of South-East Asiakutty monePas encore d'évaluation

- Indian and Chinese Immigrant Communities: Comparative PerspectivesD'EverandIndian and Chinese Immigrant Communities: Comparative PerspectivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Sino-Javanese Alliance Under The Dutch Hegemony Duringthe18th CenturyDocument9 pagesSino-Javanese Alliance Under The Dutch Hegemony Duringthe18th Centurydaya.negri.fisPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Papers On Indian CultureDocument5 pagesResearch Papers On Indian Culturegvzexnzh100% (1)

- Indian Culture Research PaperDocument5 pagesIndian Culture Research Paperntjjkmrhf100% (1)

- Unifying Themes in The History of BritisDocument32 pagesUnifying Themes in The History of BritisTasaduq Ahmad 46Pas encore d'évaluation

- Approaches To Indian HistoryDocument2 pagesApproaches To Indian HistoryhdammuPas encore d'évaluation

- University of Hawai'i Press Journal of World HistoryDocument31 pagesUniversity of Hawai'i Press Journal of World Historybiplab singhPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Tribes in Transition The Need For Reorientation (Yogesh Atal) (Z-Library)Document199 pagesIndian Tribes in Transition The Need For Reorientation (Yogesh Atal) (Z-Library)bedudnwjhsussndhPas encore d'évaluation

- Ottoman Population RecordsDocument39 pagesOttoman Population Recordsfauzanrasip100% (1)

- Research Papers On Indian HistoryDocument11 pagesResearch Papers On Indian Historyh03x2bm3100% (1)

- Citizenship in Asian HistoryDocument18 pagesCitizenship in Asian HistorymulqisPas encore d'évaluation

- History Research Paper Topics IndiaDocument4 pagesHistory Research Paper Topics IndiagvznwmfcPas encore d'évaluation

- Living Buddhism: Migration, Memory, and Castelessness in South IndiaDocument20 pagesLiving Buddhism: Migration, Memory, and Castelessness in South IndiaShuddhabrata SenguptaPas encore d'évaluation

- BCAS v14n03Document78 pagesBCAS v14n03Len HollowayPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Education and YouthDocument7 pagesNotes On Education and YouthKinga SztabaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Development of Indian CivilizationDocument46 pagesThe Development of Indian CivilizationDebra ValdezPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian History Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesIndian History Research Paper Topicsdldtcbulg100% (1)

- The English East India Company's Language Policy and the Encounter with PersianDocument34 pagesThe English East India Company's Language Policy and the Encounter with PersianTahir MubarakPas encore d'évaluation

- South Asian Sociities Are Woven Not Around States But Around Plural Cultures and Indentities PDFDocument15 pagesSouth Asian Sociities Are Woven Not Around States But Around Plural Cultures and Indentities PDFCSS DataPas encore d'évaluation

- Acehnese Culture(s) : Plurality and Homogeneity.: Prof. Dr. Susanne SchröterDocument31 pagesAcehnese Culture(s) : Plurality and Homogeneity.: Prof. Dr. Susanne SchröterTeuku Fadli SaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Bayly, Susan Introduction To Caste, Society and Politics in IndiaDocument24 pagesBayly, Susan Introduction To Caste, Society and Politics in IndiaLikitha reddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Tribal Development ThesisDocument5 pagesTribal Development Thesisanngarciamanchester100% (2)

- Chinese Culture ThesisDocument6 pagesChinese Culture Thesiscandacegarciawashington100% (2)

- Wiley Royal Institute of International AffairsDocument3 pagesWiley Royal Institute of International AffairsVishikha 2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 5 ChinaDocument25 pages5 ChinaKarina TrichikPas encore d'évaluation

- Slavery and South Asian History PDFDocument369 pagesSlavery and South Asian History PDFnazeerahmad100% (2)

- 10 Slavery and Southern AsiaDocument370 pages10 Slavery and Southern AsiaGarvey LivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Midterm Exam Instructions: From 1-5, Each of Them Is 5 Points. From 6-9, Each of Them Is 10 Points. No.10 Is 25 PointsDocument4 pagesMidterm Exam Instructions: From 1-5, Each of Them Is 5 Points. From 6-9, Each of Them Is 10 Points. No.10 Is 25 PointsonhcetumPas encore d'évaluation

- Colonial Contact in Hidden LandDocument30 pagesColonial Contact in Hidden LandEKO PRAYITNO JOKO -Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vilyatpur 1848-1968: Social and Economic Change in a North Indian VillageD'EverandVilyatpur 1848-1968: Social and Economic Change in a North Indian VillagePas encore d'évaluation

- Foundation of Indian National CongressDocument11 pagesFoundation of Indian National CongressShah12Pas encore d'évaluation

- Romila ThaparDocument24 pagesRomila ThaparEricPas encore d'évaluation

- D..J. Rycroft 1-10Document10 pagesD..J. Rycroft 1-10Devika Hemalatha DeviPas encore d'évaluation

- Nations and Nationalism (Wiley) Volume 1 Issue 1 1995 Anthony Smith Obi Igwara Athena Leoussi Terry Mulhall - EditorialDocument2 pagesNations and Nationalism (Wiley) Volume 1 Issue 1 1995 Anthony Smith Obi Igwara Athena Leoussi Terry Mulhall - EditorialSinisa LazicPas encore d'évaluation

- Westernization in Indian CultureDocument18 pagesWesternization in Indian CultureSohel BangiPas encore d'évaluation

- Recent Research On South Asia by Swedish ScholarsDocument10 pagesRecent Research On South Asia by Swedish Scholarsபூ.கொ. சரவணன்Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mso 4 em PDFDocument8 pagesMso 4 em PDFFirdosh Khan100% (1)

- The Argumentative Indian Writings On Indian History, Culture and Identity (Amartya Sen)Document426 pagesThe Argumentative Indian Writings On Indian History, Culture and Identity (Amartya Sen)divyajeevan8980% (5)

- G Aloysius - Caste in and Above HistoryDocument24 pagesG Aloysius - Caste in and Above HistoryAfthab Ellath100% (1)

- Sem 2 History ProjectDocument31 pagesSem 2 History ProjectMeenakshiVuppuluri100% (1)

- Timeline ReflectionDocument2 pagesTimeline Reflectionapi-643841412Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ottoman Population 1890 SDocument39 pagesOttoman Population 1890 SnjfewipnfwePas encore d'évaluation

- Transformation of Tribal Society 1Document8 pagesTransformation of Tribal Society 1Alok Kumar BiswalPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper Topics AsiaDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Topics Asiaaflbsjnbb100% (1)

- Kin Clan Raja and Rule: State-Hinterland Relations in Preindustrial IndiaD'EverandKin Clan Raja and Rule: State-Hinterland Relations in Preindustrial IndiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Communication As ReligionDocument4 pagesCommunication As ReligionParthapratim ChakravortyPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Queer Politics in South Asia AnDocument15 pagesNotes On Queer Politics in South Asia AnRashmi MehraPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing Identities and Caste Politics in India before MandalDocument12 pagesChanging Identities and Caste Politics in India before MandalHarshPas encore d'évaluation

- An Ethnohistorical Dictionary ChinaDocument446 pagesAn Ethnohistorical Dictionary Chinawasi_budiartoPas encore d'évaluation

- RPH Activity Midterm Tejada 2Document3 pagesRPH Activity Midterm Tejada 2deanyangg25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Review by - John Mark Kenoyer - Beyond The Gorges of The Indus - Archaeology Before Excavationby Karl Jettmar (2003)Document4 pagesReview by - John Mark Kenoyer - Beyond The Gorges of The Indus - Archaeology Before Excavationby Karl Jettmar (2003)Paper BarrackPas encore d'évaluation

- Indians in FijiDocument241 pagesIndians in FijiRukshar KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Bangladesh Rock - The Legacy of Azam Khan-LibreDocument24 pagesHistory of Bangladesh Rock - The Legacy of Azam Khan-LibrehujsedPas encore d'évaluation

- Islam in Bangladeshi SocietyDocument8 pagesIslam in Bangladeshi SocietyhujsedPas encore d'évaluation

- Bengali Folk RhymesDocument18 pagesBengali Folk RhymesKoto SalePas encore d'évaluation

- Media 165435 enDocument24 pagesMedia 165435 enhujsedPas encore d'évaluation

- Document 6 Billah A. M. M. A The Development of Bengali Literature During Muslim RuleDocument11 pagesDocument 6 Billah A. M. M. A The Development of Bengali Literature During Muslim RuleHasanzubyre100% (1)

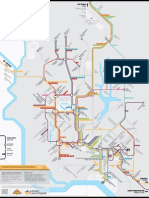

- Dhaka Bus Map-Alpha PDFDocument2 pagesDhaka Bus Map-Alpha PDFTara Vora RatePas encore d'évaluation

- BENGALI Lang and Culture PresentationDocument42 pagesBENGALI Lang and Culture Presentationhujsed100% (1)

- 9 THDocument6 pages9 THXoxxoPas encore d'évaluation

- Translation Theory Week 2Document5 pagesTranslation Theory Week 26448 Nguyễn Ngọc Tâm NhưPas encore d'évaluation

- ColonialismDocument3 pagesColonialismNikasha ChaudharyPas encore d'évaluation

- POSITION - PAPER World EnglishesDocument3 pagesPOSITION - PAPER World EnglishesPrincess Joy CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Borrowings in English - R4usnac Ecaterina - EG21ZDocument18 pagesBorrowings in English - R4usnac Ecaterina - EG21ZEkaterina RusnakPas encore d'évaluation

- Cfe2 L 52580 ks2 European Day of Languages Powerpoint - Ver - 1Document30 pagesCfe2 L 52580 ks2 European Day of Languages Powerpoint - Ver - 1Paul HasasPas encore d'évaluation

- Example: Dahlia Is From IndiaDocument5 pagesExample: Dahlia Is From Indiaсергей тютеревPas encore d'évaluation

- Charminar Pedestrianisation Project SummaryDocument2 pagesCharminar Pedestrianisation Project SummaryRENUKA UPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of English in My Life: CharlemagneDocument3 pagesThe Role of English in My Life: CharlemagneЛера КузуроPas encore d'évaluation

- Segmental and Supra Segmental PhonologyDocument2 pagesSegmental and Supra Segmental Phonologyahdia ahmed100% (2)

- The Morphemic Structure of The English LanguageDocument3 pagesThe Morphemic Structure of The English LanguageАйгера МерейPas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief History of 21st Century Philippines LiteratureDocument6 pagesA Brief History of 21st Century Philippines LiteratureLeigh Nathalie LealPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Persona Narrative Bcom 314Document2 pagesProfessional Persona Narrative Bcom 314api-546201224Pas encore d'évaluation

- Foniks and Other LiesDocument15 pagesFoniks and Other LiesRobert BruinsmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Williams 1902Document48 pagesWilliams 1902MatejaPas encore d'évaluation

- So Just Who Are The EnglishDocument2 pagesSo Just Who Are The Englishchoo zhen xing100% (1)

- The Royal Library AdditionDocument5 pagesThe Royal Library AdditionJoris KatkeviciusPas encore d'évaluation

- Year 3 Geography Oral Presentation 2Document1 pageYear 3 Geography Oral Presentation 2api-356327011Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Temples of Abu Simbel: Text by Khaled El-EnanyDocument10 pagesThe Temples of Abu Simbel: Text by Khaled El-EnanyRoshanPas encore d'évaluation

- Van Gogh Museum - BUILDINGDocument7 pagesVan Gogh Museum - BUILDINGFarra Lydia Binti Mohd ArifPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 3 Reading Comp. NewDocument4 pagesUnit 3 Reading Comp. NewSalah SalahPas encore d'évaluation

- Transcult - Nursing PPT Nurs 450 FinalDocument32 pagesTranscult - Nursing PPT Nurs 450 FinalJuan Cruz100% (1)

- American Culture in The 1950sDocument337 pagesAmerican Culture in The 1950sFiorenzo Iuliano100% (2)

- Name: Sendi Gustian Class: XI Social 2: Music Is Fun For Learning EnglishDocument3 pagesName: Sendi Gustian Class: XI Social 2: Music Is Fun For Learning EnglishGrazelle Emily VeloveyPas encore d'évaluation

- Class 7 - List of Topics To Be Covered (BSU 1.2) PDFDocument5 pagesClass 7 - List of Topics To Be Covered (BSU 1.2) PDFTalha Altaf - 45849/TCHR/GM2KPas encore d'évaluation

- BUTUANONDocument7 pagesBUTUANONHILVANO, HEIDEE B.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 9 Short Test 1A: GrammarDocument2 pagesUnit 9 Short Test 1A: GrammarСоня НизовцоваPas encore d'évaluation

- Dakshina KannadaDocument134 pagesDakshina KannadaSachidananda KiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Rome's Colosseum To Get New Hi-Tech FloorDocument9 pagesRome's Colosseum To Get New Hi-Tech FloorEnglish OnlinePas encore d'évaluation