Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Unit 6: Project Evaluation

Transféré par

Raj ChavanTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Unit 6: Project Evaluation

Transféré par

Raj ChavanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

57

UNIT 6

Project Evaluation

When cost and benefit cash flows have been estimated and combined, a

project proposal is ready for evaluation. This unit shows how to calculate

the most widely used measures of project profitability, and discusses their

use in evaluating and ranking projects.

Learning Objectives When you have completed this unit you should:

A. Know how to calculate payback, return on investment, net present

value, and internal rate of return for a project.

B. Understand the advantages and disadvantages of each method.

C. Know how to use each method to evaluate and rank proposed

projects.

6-1. Is It Worth Doing?

Many more projects are proposed than are approved. How can the pro-

posals that are most profitable to the organization be selected? Each pro-

posal must be evaluated and, if resources are limited, compared against

other proposals. Evaluation decides whether the project qualifies as profit-

able, measured against a specified organization guideline (e.g., three-year

payback, or positive net present value at 10% discount rate). If the organi-

zation has unlimited resources, a favorable evaluation is sufficient for

project approval. Otherwise, the proposal must compete against other

qualified proposals for limited resources.

To evaluate proposed investments, one must first express them on a com-

mon basis and then apply some sort of economic criterion, or profitability

index. The usual common basis is estimated cash flow. No one economic

criterion dominates the field. There are several, and each has its particular

strengths, weaknesses, and impassioned champions and detractors. The

criteria discussed in this unit are the four most widely used. They include

payback, return on investment, net present value, and internal rate of

return.

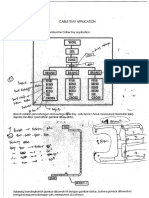

6-2. Project Cash Flow Table

A control improvement project starts as an idea. The idea takes on differ-

ent representations as it is developed. Representations may be as concrete

Friedmann05.book Page 57 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

58 UNIT 6: Project Evaluation

as a pilot plant demonstration of a proposed control scheme or as abstract

as a mathematical proof. The financial representation of a project is a

string of numbers, the expected yearly cash flows. These cash flows are the

algebraic sums of the benefit cash flows discussed in Unit 4 and the cost

cash flows covered in Unit 5. The combined cash flow table for a conven-

tional project starts with negative numbers, then switches to positive.

Example 6-1: The first costs of a four-unit control consolidation are

described in Example 5-2. The cash flows for the first costs of this project

are listed in the second column of Table 6-1. If benefits from the consolida-

tion are $40,000 per unit per year, the benefit cash flows will be $80,000 for

the second year, during which only two units will be run from the consoli-

dated control room, and $160,000/year thereafter for the life of the project.

Benefit cash flows are listed in the third column of Table 6-1. Combined

cash flows, the year-by-year algebraic sums of cost and benefit cash flows,

are listed in column four.

6-3. Nondiscounted Evaluation Methods

The earliest widely used evaluation methods are payback and return on

investment. The payback period (PP) is the time required to recover the

original capital investment from cash flow. The original capital investment

is the project first cost, and for payback calculation purposes, the cash

flows are benefits minus operating costs. PP thus can be defined as the

value that satisfies Eq. (6-1).

(6-1)

Cash Flows, $

Year Costs Benefits Combined

0 -200,000 0 -200,000

1 -190,000 0 -190,000

2 -140,000 80,000 -60,000

3 0 160,000 160,000

4 0 160,000 160,000

5 0 160,000 160,000

6 0 160,000 160,000

7 0 160,000 160,000

8 0 160,000 160,000

Table 6-1. Cash Flows for Control Consolidation

FC CF t d

0

PP

=

Friedmann05.book Page 58 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

UNIT 6: Project Evaluation 59

where:

FC = project first cost

CF = operating cash flow, not including first costs

Time is usually measured from the start of operations rather than from the

first expenditure.

Return on investment (ROI) uses the same first cost and cash flow defini-

tions. It is expressed as a percentage and measured by the ratio of average

yearly operating cash flow to first cost, as shown in Eq. (6-2).

(6-2)

where:

CF

i

= cash flow for ith year

n = project operating lifetime, in years

Example 6-2: A straightforward project has an estimated first cost,

invested at the start of the project, of $100,000. The project will take one

year before operation starts, so operating cash flows start in year 2. They

are estimated to be $40,000 per year for eight years. The overall cash flow

diagram is shown as Fig. 6-1. Payout period is 2.5 years, the time after

start-up at which operating cash flow equals first cost. ROI = 100 x

$40,000/100,000 = 40%.

Payback and ROI have similar advantages and disadvantages. Both are

easy to understand and easy to compute. Neither explicitly takes into

account the time value of money, since future cash flows are not dis-

counted as a function of time. As a result, these methods are biased in the

values placed on some cash flows compared to the discount methods cov-

ered in 6.4. Payback places no value on cash flows beyond those required

to cover first cost. ROI places equal value on immediate and remote cash

flows. These biases are not important if all the projects being compared

have similar lifetimes and cash flow trajectories. They can produce bad

decisions when comparing dissimilar projects. Payback and ROI have

been largely superseded by the discounted evaluation methods discussed

in the next section.

ROI 100 CF

i

( ) n

i 1 =

n

FC ( ) =

Friedmann05.book Page 59 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

60 UNIT 6: Project Evaluation

6-4. Discounted Evaluation Methods

The evaluation methods recommended by most economists are net present

value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR). Both of these methods take

into account the time value of money by discounting future cash flows as a

function of time. The time value of money is simply the effect of interest.

The future value (FV) of a present value (PV) after n years is determined

by Eq. (6-3), the compound interest formula.

FV

n

= PV (1 + k)

n

(6-3)

where k is the yearly fractional interest rate.

Table 6-2 shows a few future values of one dollar as a function of interest

rate and time. Discount factors for future values are calculated by rear-

ranging Eq. (6-3) into Eq. (6-4) to solve for PV.

PV = FV

n

/(l + k)

n

(6-4)

Fig. 6-1. Cash Flow Diagram for Example 6-2

Interest Rate

Year 5% 10% 20%

1 1.050 1.100 1.200

5 1.276 1.611 2.488

10 1.629 2.594 6.192

Table 6-2. Compounded Future Value of $1

Friedmann05.book Page 60 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

UNIT 6: Project Evaluation 61

The present value of one dollar of future value is the discount factor that

must be applied when evaluating future cash flow. Some discount factors

are plotted in Fig. 6-2 and listed in Table 6-3. Note that the entries in this

table are simply the inverse of the entries in Table 6-2.

Fig. 6-2. Discount Factor for Future Values

Interest Rate

Year 5% 10% 20%

1 0.952 0.909 0.833

5 0.784 0.621 0.402

10 0.614 0.386 0.161

Table 6-3. Discount Factors

Friedmann05.book Page 61 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

62 UNIT 6: Project Evaluation

If interest rate k is set at the cost of capital, the net present value of a string

of cash flows (CF

i

) over n years can be calculated by repeated application

of Eq. (6-4), as follows:

(6-5)

The project represented by the string of cash flows should be approved if

NPV is positive, since a positive value of NPV indicates that investment in

the project will earn at a rate greater than k. For instance, if capital can be

obtained by borrowing at 10%, a project with an NPV of $20,000 at k = 0.10

will yield $20,000 over and above interest costs.

The calculation procedure for internal rate of return uses the NPV calcula-

tion as a means to a different end. An unknown rate of return (r) is substi-

tuted for cost of capital (k) in Eq. (6-5), producing Eq. (6-6).

(6-6)

The internal rate of return (IRR) is that value of r which will result in a

zero value of NPV. Eq. (6-6) cannot be solved explicitly for r, so finding

IRR is a trial-and-error procedure. Those projects with an IRR greater than

a specified target rate should be approved.

Example 6-3: The cash flows for Example 6-2, shown in Fig. 6-1, can also

be used to calculate NPV and IRR. If a pretax cost of capital of 15% is

assumed, NPV can be calculated from Eq. (6-5) as follows:

NPV = -100,000 + 0 + 40,000/(1.15)

2

...40,000/(1.15)

9

= $56,081

IRR must be greater than 15%, since NPV is positive at that rate of return.

A rate of 30% produces a negative NPV of -10,009, so IRR must be less

than 30%, but closer to 30% than 15%. Two interpolations yield an IRR of

26.8%. Fig. 6-3 shows the effect of rate of return on NPV.

NPV of a nonconventional project may equal zero at more than one dis-

count rate, producing multiple internal rates of return. A necessary but

not sufficient condition is at least two changes of sign for cash flow. See

Exercise 6-10 for an example. Methods have been proposed (Ref. 1) to deal

NPV CF

0

CF

1

1 k + ( ) CF

2

1 k + ( )

2

CF

n

1 k + ( )

n

+ + +

CF

0

CF

i

1 k + ( )

i

( )

i 1 =

n

+

=

=

NPV CF

0

CF

i

1 r + ( )

i

( )

i 1 =

n

+ =

Friedmann05.book Page 62 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

UNIT 6: Project Evaluation 63

with these cases by identifying a single relevant rate of return for use in

determining project acceptability.

The advantage of these discount-based methods over payback and ROI is

their consistent valuation of future cash flows. Their historical disadvan-

tage, which limited their acceptance for a long time, is more difficult calcu-

lation. This objection is now irrelevant. Many calculator and personal

computer programs, especially spreadsheets, can be used for NPV and

IRR calculation.

NPV and IRR are equivalent methods for project evaluation, and the

choice between them for this purpose is a matter of taste. If the target rate

is set equal to the cost of capital and no other restrictions apply, the use of

NPV or IRR will produce identical results. They will not necessarily pro-

duce identical rankings, so care should be taken to use the appropriate

method when projects must be rank ordered. These situations are dis-

cussed in Section 6-6.

6-5. Using a Spreadsheet

Calculation of NPV using pencil and paper is slow and tedious. Calcula-

tion of IRR is even more repetitive, since it involves a trial-and-error pro-

cedure. For any problems more complex than evaluation of a single set of

Fig. 6-3. Effect of Rate of Return on NPV in Example 6-3

Friedmann05.book Page 63 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

64 UNIT 6: Project Evaluation

cash flows, the easiest way to get NPV and IRR values is through the use

of a spreadsheet program. The most popular spreadsheets, including the

widely used Excel

, have built-in NPV and IRR functions.

Operation of a computer spreadsheet is essentially an information entry

process. Calculation and display are automatically and immediately per-

formed when information is received. When an entry in one cell is

changed, all the dependent cells are altered to reflect that change. This fea-

ture allows rapid evaluation of alternatives.

Spreadsheets are particularly useful for contingency or what-if studies.

Once the original cash flows and function calls have been entered, each

change in cash flow immediately produces changes in the displayed val-

ues of NPV and IRR. Fig. 6-4 is a typical project evaluation printout from a

spreadsheet. Cash flows, discount rate, NPV, and IRR are shown. Only the

cash flow entries need to be altered to find the effects of a changed situa-

tion. The effect of a delayed start-up is shown in Fig. 6-5. The delay wipes

out cash flow for the first year, affecting NPV and IRR. Only the entry for

year one cash flow had to be changed. NPV and IRR were automatically

recalculated. All the engineering economy textbooks cited in Appendix A

have detailed descriptions of spreadsheet use for project evaluation.

6-6. Selection Among Proposals

The situation in which all projects are independent and the choice among

them is unlimited is an idealized state, more commonly encountered in

textbooks than in the real world. There are several ways to classify the

constraints that often limit project selection.

Fig. 6-4. Spreadsheet Project Evaluation Printout

Friedmann05.book Page 64 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

UNIT 6: Project Evaluation 65

Choice may be limited because multiple projects seek the same object. A

proposal to replace existing controls with a DCS cannot be evaluated inde-

pendently of a proposal to replace the same controls with multiple PLCs.

Acceptance of one proposal forecloses the opportunity for the other one.

Choice may also be limited by resource availability. The scarce resource

may be skilled labor (the process engineer who knows the plant has only

enough time to work on one control project) or productive capacity (the

only two plants making left-handed widgets cannot both be shut down for

control retrofits). In most cases the scarce resource is capital.

Capital investment literature uses a somewhat different classification

scheme. Opportunity-limited situations are lumped with those limited by

availability of resources other than capital. The conflicting projects are

mutually exclusive. The decision that must be made is no longer whether a

project qualifies for investment under organization guidelines, but which

one among qualifying proposals is most attractive. In this situation NPV

and IRR can produce different results. The literature includes many dis-

cussions (see Ref. 2 for example) of the conditions for which the two meth-

ods have ranking conflicts.

Example 6-4: Cash flows for mutually exclusive proposals A and B are

listed in Table 6-4. The required rate of return is equal to the cost of capital

at 10%, so both proposals qualify easily. NPV of proposal A at 10% cost of

capital is $6,699; IRR is 22%. NPV of proposal B is $7,136; IRR is 18.3%. If

projects are ranked by NPV, proposal B will be selected. If IRR is used,

proposal A will be selected.

NPV is considered to be the sounder methodology for ranking of mutually

exclusive proposals. It assumes that cash flows can be reinvested at the

cost of capital, while IRR assumes that cash flows can be reinvested to earn

Fig. 6-5. Spreadsheet Project Evaluation Printout after Cash Flow Change

Friedmann05.book Page 65 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

66 UNIT 6: Project Evaluation

the calculated rate of return. The NPV assumption is more conservative

and more likely.

The other restricted situation treated in the capital investment literature is

limited availability of capital, known as capital rationing. Theoretically,

capital should be available for any worthwhile project (i.e., one that will

earn a higher rate than the cost of capital). Actually, capital may be limited

for any number of reasons. Firms may limit capital expenditures because

of credit limits or fear of the market effects of increased borrowing. Divi-

sions and individual plants, where most decisions on control improve-

ment projects are made, are almost always subject to limits on the amount

of capital that can be committed without approval of higher authority.

There are usually more qualifying proposals than can be funded with

available capital, so some means must be found to discriminate among

them and select the most profitable.

Net present value is not very useful as a tool for this selection process. The

project with the largest NPV is expected to make the most money, but it

may not be the most efficient use of capital. The discount rate for NPV

might be raised until total capital outlay for qualified proposals is equal to

or less than the capital limit, but this is equivalent to reinventing internal

rate of return. It is simpler to use IRR directly. Projects are selected by

starting with the highest IRR and proceeding down the list until the capi-

tal limit is reached. Another possible method for ranking projects uses the

ratio of the net present value of net cash inflows to the initial investment.

This ratio is called the profitability index (Ref. 3). Profitability rankings

should be similar to those obtained using IRR.

Cash Flows, $

Year Project A Project B

0 -25,000 -25,000

1 10,000 0

2 10,000 5,000

3 10,000 10,000

4 10,000 30,000

Table 6-4. Mutually Exclusive Proposals

Friedmann05.book Page 66 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

UNIT 6: Project Evaluation 67

References

1. Hartman, J.C. and Schafrick, I.C., 2004. The Relevant Internal

Rate of Return. Engineering Economist 49, 3, pp. 139-155.

2. Barney, L.D. and Danielson, M.G., 2004. Ranking Mutually

Exclusive Projects: the Role of Duration. Engineering Economist

49, 1, pp. 43-61.

3. Peterson. S. and Pugh, D., 2005. How to Make a Good Capital

Decision. InTech 52. 3, p. 50.

4. Park C. S., 2002. Contemporary Engineering Economics (3d ed.), p.

809. Prentice-Hall.

Exercises

6-1. Payback is sometimes known as the fish-bait method of project

evaluation. Why?

6-2. Calculate payback, ROI, NP and IRR for the project for which cash flows

are listed in Table 6-2. Use a 10% discount rate.

6-3. The discount factor for earnings 5 years hence is known to be 0.497. What

is the percentage discount rate?

6-4. A firm evaluates proposals using a discount rate of 20%. This rate is

considerably higher than the cost of capital, which is available at 10%. List

some possible reasons for this behavior.

6-5. Payback, ROI, NP and IRR for the cash flows shown in Fig. 6-1 were

calculated in Examples 6-2 and 6-3. Which of these profitability measures

would be affected if the project started earning immediately instead of one

year after initial expenditures?

6-6. Two projects, A and B, are proposed for the same unit. Each project consists

of installation of a PLC to control a different part of the unit. Expected cash

flows for the projects are listed in Table 6-5. The criterion for project

approval is positive net present value at a discount rate of 15%. Which

projects should be approved?

Friedmann05.book Page 67 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

68 UNIT 6: Project Evaluation

6-7. If the PLCs for the projects in Exercise 6-6 lose power, failure may be

catastrophic. The PLCs should, therefore, be powered by an uninterruptible

power supply (UPS). An already installed UPS has the capacity to handle

one but not both PLCs. A new UPS to handle one PLC would cost $5000.

In this situation, which projects should be approved?

6-8. Under what circumstances can capital rationing make projects mutually

exclusive? Give an example.

6-9. In the example given in the solution to Exercise 6-8, what will happen if the

capital limit is less than $800,000? greater than $1,500,000?

6-10. Since you have demonstrated your mastery of the subject by reaching this

exercise, you have been asked to write a sequel to this unit. You are offered

an immediate $1000 cash payment, and royalty payments after completion

of the book are estimated to be $2000/year for 3 years. The book will take one

year to complete, and during that year you must forgo a consulting project

that would have earned you $5000. Is this an attractive proposal? What

range of discount rates would result in positive NPV?

Cash Flows, $

Year Project A Project B

0 -10,000 -10,000

1 3,000 -5,000

2 3,000 5,000

3 3,000 5,000

4 3,000 5,000

5 3,000 5,000

6 3,000 5,000

7 3,000 5,000

Table 6-5. Cash Flows for Exercise 6-6

Friedmann05.book Page 68 Tuesday, June 13, 2006 11:31 AM

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Systematic Investment Plans Mba ProjectDocument69 pagesSystematic Investment Plans Mba ProjectMaheshwari Stephen Pinto87% (150)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Notes IAS 19Document18 pagesNotes IAS 19Nasir IqbalPas encore d'évaluation

- Pdms Cable TrayDocument10 pagesPdms Cable TrayRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cs01304den 0112Document2 pagesCs01304den 0112Raj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Instrumentation Cables: BS 5308, Part 1 BS 5308, Part 2 and Gen. To BS 5308, Part 1Document88 pagesInstrumentation Cables: BS 5308, Part 1 BS 5308, Part 2 and Gen. To BS 5308, Part 1Raj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Proline Prosonic Flow 93W: Technical InformationDocument32 pagesProline Prosonic Flow 93W: Technical InformationRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Annexure For Pressure GaugeDocument2 pagesAnnexure For Pressure GaugeRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- XFDocument1 pageXFRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Drak A Mog CatalogDocument376 pagesDrak A Mog Catalogdadok999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Marine Electrical KnowledgeDocument53 pagesMarine Electrical KnowledgeRhn RhnPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Has 4-20 Ma Gained So Much Acceptance and Survived So Long?Document2 pagesWhy Has 4-20 Ma Gained So Much Acceptance and Survived So Long?Raj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- DVR Vs NVRDocument3 pagesDVR Vs NVRGvds SastryPas encore d'évaluation

- His AtlDocument7 pagesHis AtlRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- PL2303 XP2K Driver Revision NotesDocument1 pagePL2303 XP2K Driver Revision NotesPolo AlvarezPas encore d'évaluation

- What Does NAMUR NE 43 Do ForDocument1 pageWhat Does NAMUR NE 43 Do ForRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Siemens PTC RTD Thermocouples Section7 Rev1Document16 pagesSiemens PTC RTD Thermocouples Section7 Rev1DelfinshPas encore d'évaluation

- Surge Protec IIDocument14 pagesSurge Protec IIRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- SU-FMO Fire Alarm System Basics Presentation To Building Managers 7-28-2014Document30 pagesSU-FMO Fire Alarm System Basics Presentation To Building Managers 7-28-2014Ahmed MohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- One NoteDocument11 pagesOne NoteRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- EINTH012Document32 pagesEINTH012Raj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- and 330425 Accelerometer Acceleration Transducers - Datasheet - 141638 - Cda - 000 PDFDocument8 pagesand 330425 Accelerometer Acceleration Transducers - Datasheet - 141638 - Cda - 000 PDFdialixhPas encore d'évaluation

- His AtlDocument7 pagesHis AtlRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Area Classification: (IEC/EN 60529)Document1 pageArea Classification: (IEC/EN 60529)nestkwt1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chem Earth PointsDocument65 pagesChem Earth PointsRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Unitronics IdntolvurDocument24 pagesUnitronics IdntolvurRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 18 FiltrationDocument18 pagesChapter 18 FiltrationGMDGMD11Pas encore d'évaluation

- Why Has 4-20 Ma Gained So Much Acceptance and Survived So Long?Document2 pagesWhy Has 4-20 Ma Gained So Much Acceptance and Survived So Long?Raj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- BN330500dt PDFDocument19 pagesBN330500dt PDFvvPas encore d'évaluation

- Schneider Electric - Overload Relay Trip CurvesDocument84 pagesSchneider Electric - Overload Relay Trip CurvesMichael Parohinog GregasPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 8:: Including Risks in Cost EstimationsDocument7 pagesUnit 8:: Including Risks in Cost EstimationsRaj ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Study Guide AC305 Final ExamDocument1 pageStudy Guide AC305 Final Examebonybryant100% (2)

- ECON 365 NotesDocument82 pagesECON 365 Notesrushikesh KanirePas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Long-Term Financial ConceptsDocument40 pagesBasic Long-Term Financial ConceptsBr. Ivan Karlo Umali FSCPas encore d'évaluation

- Focus On Personal Finance 5th Edition Kapoor Solutions ManualDocument23 pagesFocus On Personal Finance 5th Edition Kapoor Solutions ManualDeanPetersrpmik100% (16)

- Mercader ACC 115-Q5 Finance Lease 2Document2 pagesMercader ACC 115-Q5 Finance Lease 2Mannuelle GacudPas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring Microsoft Office 2013 Volume 2 1St Edition Poatsy Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument33 pagesExploring Microsoft Office 2013 Volume 2 1St Edition Poatsy Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFJohnCraiggmyrp100% (13)

- Chapter 14Document9 pagesChapter 14aamna0% (2)

- Jcsgo Christian Academy: Senior High School DepartmentDocument4 pagesJcsgo Christian Academy: Senior High School DepartmentFredinel Malsi ArellanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Bus Fin Module 4 Basic Long-Term Financial ConceptsDocument21 pagesBus Fin Module 4 Basic Long-Term Financial ConceptsMariaShiela PascuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gross Profit - Margin RatioDocument16 pagesGross Profit - Margin RatioaaronPas encore d'évaluation

- The Math of Intrinsic ValueDocument33 pagesThe Math of Intrinsic ValuelogeshmechPas encore d'évaluation

- FV FV: ExplanationDocument54 pagesFV FV: Explanationenergizerabby83% (6)

- L7796 Otm Workbook KenyaDocument80 pagesL7796 Otm Workbook Kenyaangela mwangiPas encore d'évaluation

- Fundamentals of Managerial Economics: Prepared By: Prof. Rebecca T. GorospeDocument29 pagesFundamentals of Managerial Economics: Prepared By: Prof. Rebecca T. GorospeyelzPas encore d'évaluation

- Time Value of MoneyDocument15 pagesTime Value of MoneytamtradePas encore d'évaluation

- ICAI - Question BankDocument6 pagesICAI - Question Bankkunal mittalPas encore d'évaluation

- Principles of Corporate FinanceDocument36 pagesPrinciples of Corporate FinanceOumayma KharbouchPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1 - Financial Liabilities (AP & NP)Document38 pagesModule 1 - Financial Liabilities (AP & NP)faye pantiPas encore d'évaluation

- S16 - Scenario Manager - NPVDocument9 pagesS16 - Scenario Manager - NPVSRISHTI ARORAPas encore d'évaluation

- QF2101 1112S1 Tutorial 3Document3 pagesQF2101 1112S1 Tutorial 3Wei Chong KokPas encore d'évaluation

- Quiz Notes and Loans Receivable SY 2022 2023 SolutionDocument4 pagesQuiz Notes and Loans Receivable SY 2022 2023 Solutionreagan blairePas encore d'évaluation

- CFM 221 2023 Capital Budgets NotesDocument19 pagesCFM 221 2023 Capital Budgets NotesChantell KatlegoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pak Economy: (B) Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy (C) SixthDocument15 pagesPak Economy: (B) Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy (C) SixthSOHAIB HKPas encore d'évaluation

- Net Present Value (NPV) Definition - Calculation - ExamplesDocument3 pagesNet Present Value (NPV) Definition - Calculation - ExamplesKadiri OlanrewajuPas encore d'évaluation

- FIDIC RED BOOK History and ComparisonDocument83 pagesFIDIC RED BOOK History and ComparisonMubasher AwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Financed PascoDocument41 pagesBusiness Financed Pascoedadzie338Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ch17 InvestmentsDocument38 pagesCh17 InvestmentsRhedeline LugodPas encore d'évaluation

- Cpa A2.1 - Strategic Corporate Finance - Study ManualDocument206 pagesCpa A2.1 - Strategic Corporate Finance - Study ManualDamascene100% (2)