Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Legislative Department Case Digest

Transféré par

iyangtotTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Legislative Department Case Digest

Transféré par

iyangtotDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1

Santiago v comelec

Political Law Separation of Powers

On 6 December 1996, Atty. Jesus S. Delfin filed with COMELEC a Petition to

Amend the Constitution to Lift Term Limits of elective Officials by Peoples

Initiative The COMELEC then, upon its approval, a.) set the time and dates for

signature gathering all over the country, b.) caused the necessary publication of

the said petition in papers of general circulation, and c.) instructed local election

registrars to assist petitioners and volunteers in establishing signing stations. On

18 Dec 1996, MD Santiago et al filed a special civil action for prohibition

against the Delfin Petition. Also, Raul Roco filed with the COMELEC a motion

to dismiss the Delfin petition, the petition having been untenable due to the

foregoing. Santiago argues among others that the Peoples Initiative is limited

to amendments to the Constitution NOT a revision thereof. The extension or the

lifting of the term limits of those in power (particularly the President)

constitutes revision and is therefore beyond the power of peoples initiative.

The respondents argued that the petition filed by Roco is pending under the

COMELEC hence the Supreme Court cannot take cognizance of it.

ISSUE: Whether or not the Supreme Court can take cognizance of the case.

HELD: COMELEC acted without jurisdiction or with grave abuse of discretion

in entertaining the Delfin petition.Since the Delfin Petition is not the initiatory

petition under R.A. No. 6735 and COMELEC Resolution No. 2300, it cannot be

entertained or given cognizance of by the COMELEC. The respondent

Commission must have known that the petition does not fall under any of the

actions or proceedings under the COMELEC Rules of Procedure or under

Resolution No. 2300, for which reason it did not assign to the petition a docket

number. Hence, the said petition was merely entered as UND, meaning,

undocketed. That petition was nothing more than a mere scrap of paper, which

should not have been dignified by the Order of 6 December 1996,

the hearing on 12 December 1996, and the order directing Delfin and the

oppositors to file their memoranda or oppositions. In so dignifying it, the

COMELEC acted without jurisdiction or with grave abuse of discretion and

merely wasted its time, energy, and resources. Being so, the Supreme Court can

then take cognizance of the petition for prohibition filed by Santiago

notwithstanding Rocos petition. COMELEC did not even act on Rocos

petition. In the final analysis, when the system of constitutional law is

threatened by the political ambitions of man, only the Supreme Court can

save a nation in peril and uphold the paramount majesty of the

Constitution. It must be recalled that intervenor Roco filed with the

COMELEC a motion to dismiss the Delfin Petition on the ground that the

COMELEC has no jurisdiction or authority to entertain the petition. The

COMELEC made no ruling thereon evidently because after having heard the

arguments of Delfin and the oppositors at the hearingon 12 December 1996, it

required them to submit within five days their memoranda or

oppositions/memoranda. Earlier, or specifically on 6 Dec 1996, it practically

gave due course to the Delfin Petition by ordering Delfin to cause the

publication of the petition, together with the attached Petition for Initiative, the

signature form, and the notice of hearing; and by setting the case for hearing.

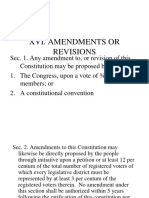

Amendment to the Constitution

On 6 Dec 1996, Atty. Jesus S. Delfin filed with COMELEC a Petition to

Amend the Constitution to Lift Term Limits of elective Officials by Peoples

Initiative The COMELEC then, upon its approval, a.) set the time and dates for

signature gathering all over the country, b.) caused the necessary publication of

the said petition in papers ofgeneral circulation, and c.) instructed local election

registrars to assist petitioners and volunteers in establishing signing stations. On

18 Dec 1996, MD Santiago et al filed a special civil action for prohibition

against the Delfin Petition. Santiago argues that 1.) the constitutional provision

on peoples initiative to amend the constitution can only be implemented by law

to be passed by Congress and no such law has yet been passed by

Congress,2.) RA 6735 indeed provides for three systems of initiative

namely, initiative on the Constitution, on statues and on local legislation. The

two latter forms of initiative were specifically provided for in Subtitles II and

III thereof but no provisions were specifically made for initiatives on the

Constitution. This omission indicates that the matter of peoples initiative to

amend the Constitution was left to some future law as pointed out by former

Senator Arturo Tolentino.

ISSUE: Whether or not RA 6735 was intended to include initiative

on amendments to the constitution and if so whether the act, as worded,

adequately covers such initiative.

HELD: RA 6735 is intended to include the system of initiative on amendments

to the constitution but is unfortunately inadequate to cover that system. Sec 2 of

Article 17 of the Constitution provides: Amendments to this constitution may

likewise be directly proposed by the people through initiative upon a petition of

at least twelve per centum of the total number of registered voters, of which

every legislative district must be represented by at least there per centum of the

registered voters therein. . . The Congress shall provide for the implementation

of the exercise of this right This provision is obviously not self-executory as it

needs an enabling law to be passed by Congress. Joaquin Bernas, a member of

the 1986 Con-Con stated without implementing legislation Section 2, Art 17

cannot operate. Thus, although this mode of amending the constitution is a

mode of amendment which bypasses Congressional action in the last analysis is

still dependent on Congressional action. Bluntly stated, the right of the people

to directly propose amendments to the Constitution through the system of

inititative would remain entombed in the cold niche of the constitution until

Congress provides for its implementation. The people cannot exercise such

2

right, though constitutionally guaranteed, if Congress for whatever reason does

not provide for its implementation.

***Note that this ruling has been reversed on November 20, 2006 when ten

justices of the SC ruled that RA 6735 is adequate enough to enable such

initiative. HOWEVER, this was a mere minute resolution which reads in part:

Ten (10) Members of the Court reiterate their position, as shown by their

various opinions already given when the Decision herein was promulgated, that

Republic Act No. 6735 is sufficient and adequate to amend the Constitution thru

a peoples initiative.

As such, it is insisted that such minute resolution did not become stare decisis.

Political Law Revision vs Amendment to the Constitution

On 6 Dec 1996, Atty. Jesus S. Delfin filed with COMELEC a Petition to

Amend the Constitution to Lift Term Limits of elective Officials by Peoples

Initiative The COMELEC then, upon its approval, a.) set the time and dates for

signature gathering all over the country, b.) caused the necessary publication of

the said petition in papers ofgeneral circulation, and c.) instructed local election

registrars to assist petitioners and volunteers in establishing signing stations. On

18 Dec 1996, MD Santiago et al filed a special civil action for prohibition

against the Delfin Petition. Santiago argues among others that the Peoples

Initiative is limited to amendments to the Constitution NOT a revision thereof.

The extension or the lifting of the term limits of those in power (particularly the

President) constitutes revision and is therefore beyond the power of peoples

initiative.

ISSUE: Whether the proposed Delfin petition constitutes amendment to the

constitution or does it constitute arevision.

HELD: The Delfin proposal does not involve a mere amendment to, but

a revision of, the Constitution because, in the words of Fr. Joaquin Bernas, SJ.,

it would involve a change from a political philosophy that rejects unlimited

tenure to one that accepts unlimited tenure; and although the change might

appear to be an isolated one, it can affect other provisions, such as, on

synchronization of elections and on the State policy of guaranteeing equal

access to opportunities for public service and prohibiting political dynasties.

A revisioncannot be done by initiative which, by express provision of Section 2

of Article XVII of the Constitution, is limited to amendments. The prohibition

against reelection of the President and the limits provided for all other national

and local elective officials are based on the philosophy of governance, to open

up the political arena to as many as there are Filipinos qualified to handle the

demands of leadership, to break the concentration of political and economic

powers in the hands of a few, and to promote effective proper empowerment for

participation in policy and decision-making for the common good; hence, to

remove the term limits is to negate and nullify the noble vision of the 1987

Constitution.

SUBIC BAY METROPOLITAN AUTHORITY

vs.

COMELEC

G.R. No. 125416 September 26, 1996FACTS:

March 13, 1992, Congress enacted

RA. 7227(The Bases Conversion and Development Act of 1992), which created

the Subic Economic Zone. RA 7227 likewise created SBMA to implement the

declared national policy of converting the Subic military reservation into

alternative productive uses.

November 24, 1992, the American navy turned over the Subic military

reservation to the Philippines government. Immediately, petitioner commenced

the implementation of its task, particularly the preservation of the sea-ports,

airport, buildings, houses and other installations left by the American navy.

On April 1993, the Sangguniang Bayan of Morong, Bataan passed

Pambayang Kapasyahan Bilang 10 , Serye 1993, expressing therein its absolute

concurrence, as required by said Sec. 12 of RA 7227, to join the Subic Special

Economic Zone and submitted such to the Office of the President.

May 24, 1993, respondents Garcia filed a petition with the Sangguniang

Bayan of Morong to annul Pambayang Kapasyahan Blg.10, Serye 1993.

The petition prayed for the following: a) to nullify Pambayang Kapasyang

Blg. 10 for Morong to join the Subic Special Economic Zone, b) to allow

Morong to join provided conditions are met.

Sangguniang Bayan ng Morong acted upon the petition by promulgating

Pambayang Kapasyahan Blg. 18, Serye 1993, requesting Congress of the

Philippines so amend certain provisions of RA 7227.

satisfied, respondents resorted to their power initiative under theLGC of

1991.

July 6, 1993, COMELEC denied the petition for local initiative on the

ground that the subject thereof was merely a resolution and not an ordinance.

February 1, 1995, the President issued Proclamation No. 532

defining the metes and bounds of the SSEZ including therein the portion of the

former naval base within the territorial jurisdiction of the Municipality of

Morong.

June 18, 19956, respondent Comelec issued Resolution No. 2845and2848,

adopting a "Calendar of Activities for local referendum

And providing for "the rules and guidelines to govern the conduct of the

referendum

3

July 10, 1996, SBMA instituted a petition for certiorari

Contesting the validity of Resolution No. 2848 alleging that public respondent

is intent on proceeding with a local initiative that proposes an amendment of a

national law

ISSUE:

1. WON Comelec committed grave abuse of discretion in promulgating

Resolution No. 2848 which governs the conduct of the referendum proposing

to annul or repeal Pambayang Kapasyahan Blg. 10

2. WON the questioned local initiative covers a subject within the powers of

the people of Morong to enact; i .e., whether such initiative "seeks the

amendment of a national law."

HELD:

1.YES. COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion. FIRST. The process

started by private respondents was an INITIATIVE but respondent Comelec

made preparations for a REFERENDUM only. In fact, in the body of the

Resolution as reproduced in the footnote below, the word "referendum" is

repeated at least 27 times, but "initiative" is not mentioned at all. The Comelec

labeled the exercise as a "Referendum"; the counting of votes was entrusted to a

"Referendum Committee"; the documents were called "referendum returns"; the

canvassers, "Referendum Board of Canvassers" and the ballots themselves bore

the description "referendum". To repeat, not once was the word "initiative" used

in said body of Resolution No. 2848. And yet, this exercise is unquestionably an

INITIATIVE.As defined, Initiative is the power of the people to propose

bills and laws, and to enact or reject them at the polls independent of

the legislative assembly. On the other hand, referendum is the right reserved to

the people to adopt or reject any act or measure which has been passed by a

legislative body and which in most cases would without action on the part of

electors become a law. In initiative and referendum, the Comelec exercises

administration and supervision of the process itself, akin to its powers over the

conduct of elections.

These law-making powers belong to the people, hence the respondent

Commission cannot control or change the substance or the content

of legislation.

2. The local initiative is NOT ultra vires because the municipal resolution is

still in the proposal stage and not yet an approved law.

The municipal resolution is still in the proposal stage. It is not yet an approved

law. Should the people reject it, then there would be nothing to contest and to

adjudicate. It is only when the people have voted for it and it has become an

approved ordinance or resolution that rights and obligations can be enforced or

implemented thereunder. At this point, it is merely a proposal and the writ or

prohibition cannot issue upon a mere conjecture or possibility. Constitutionally

speaking, courts may decide only actual controversies, not hypothetical

questions or cases. In the present case, it is quite clear that the Court

has authority to review Comelec Resolution No. 2848 to determine the

commission of grave abuse of discretion. However, it does not have the

same authority in regard to the proposed initiative since it has not

been promulgated or approved, or passed upon by any "branch

or instrumentality" or lower court, for that matter. The Commission on

Elections itself has made no reviewable pronouncements about the issues

brought by the pleadings. The Comelec simply included verbatim the proposal

in its questioned Resolution No. 2848. Hence, there is really no decision or

action made by a branch, instrumentality or court which this Court could take

cognizance of and acquire jurisdiction over, in the exercise of its review

powers.

GARCIA ET AL. VS COMELEC

G.R. No. 111511 October 5, 1993 [Initiative and Referendum; Recall

proceeding]

FACTS:

Enrique T. Garcia was elected governor of Bataan in the 1992 elections. Some

mayors, vice-mayors and members of the Sangguniang Bayan of the twelve

(12) municipalities of the province constituted themselves into a Preparatory

Recall Assembly to initiate the recall election of petitioner Garcia. They issued

Resolution No. 1 as formal initiation of the recall proceedings. COMELEC

scheduled the recall election for the gubernatorial position of Bataan.

Petitioners then filed a petition for certiorari and prohibition with writ of

preliminary injunction to annul the Resolution of the COMELEC because the

PRAC failed to comply with the "substantive and procedural requirement" laid

down in Section 70 of R.A. 7160 (Local Government Code 1991). They pointed

out the most fatal defect of the proceeding followed by the PRAC in passing the

Resolution: the deliberate failure to send notices of the meeting to 65 members

of the assembly.

ISSUES:

1) Whether or not the people have the sole and exclusive right to initiate recall

proceedings.

2) Whether or not the procedure for recall violated the right of elected local

public officials belonging to the political minority to equal protection of the

law.

RULING:

4

1) No. The history of Section 70 reveals a conscious effort on the part of our

lawmakers to institute an alternative mode of initiating recall apart from the old

means of commencement of the process solely by the people. The lawmakers

had observed that the mode was almost impossible to implement and had been

poorly used, thus precipitating the enactment of Section 3 Article X, which

sought to provide for a more responsible and accountable system of

decentralization with effective means of recall

There is nothing in the Constitution that will remotely suggest that the people

have the "sole and exclusive right to decide on whether to initiate a recall

proceeding." The Constitution did not provide for any mode, let alone a single

mode, of initiating recall elections.

The mandate given by section 3 of Article X of the Constitution is for Congress

to "enact a local government code which shall provide for a more responsive

and accountable local government structure through a system of

decentralization witheffective mechanisms of recall, initiative, and referendum .

. ." By this constitutional mandate, Congress was clearly given the power to

choose the effective mechanisms of recall as its discernment dictates.

What the Constitution simply required is that the mechanisms of recall, whether

one or many, to be chosen by Congress should be effective. Using its

constitutionally granted discretion, Congress deemed it wise to enact an

alternative mode of initiating recall elections to supplement the former mode of

initiation by direct action of the people. The legislative records reveal there

were two (2) principal reasons why this alternative mode of initiating the recall

process thru an assembly was adopted, viz: (a) to diminish the difficulty of

initiating recall thru the direct action of the people; and (b) to cut down on its

expenses.

2) No. Under the Sec. 70 of the LGC, all mayors, vice-mayors and sangguniang

members of the municipalities and component cities are made members of the

preparatory recall assembly at the provincial level. Its membership is not

apportioned to political parties. No significance is given to the political

affiliation of its members. Secondly, the preparatory recall assembly, at the

provincial level includes all the elected officials in the province concerned.

Considering their number, the greater probability is that no one political party

can control its majority. Thirdly, sec. 69 of the Code provides that the only

ground to recall a locally elected public official is loss of confidence of the

people. The members of the PRAC are in the PRAC not in representation of

their political parties but as representatives of the people. By necessary

implication, loss of confidence cannot be premised on mere differences in

political party affiliation. Indeed, our Constitution encourages multi-party

system for the existence of opposition parties is indispensable to the growth and

nurture of democratic system. Clearly then, the law as crafted cannot be faulted

for discriminating against local officials belonging to the minority.

Moreover, the law instituted safeguards to assure that the initiation of the recall

process by a preparatory recall assembly will not be corrupted by extraneous

influences. We held that notice to all the members of the recall assembly is a

condition sine qua non to the validity of its proceedings. The law also requires a

qualified majority of all the preparatory recall assembly members to convene in

session and in a public place. Needless to state, compliance with these

requirements is necessary, otherwise, there will be no valid resolution of recall

which can be given due course by the COMELEC.

Evardone v. Comelec, 204 SCRA 464, 472, December 2, 1991

Petitioner: Felipe Evardone

Respondents: Comelec, Alexander Apelado, Victorino Aclana and Noel NivalPonente: Padilla

Facts:

Felipe Evardone the mayor of Sulat, Eastern Samar, having been elected to the position during the

1988 local elections. He assumed office immediately after proclamation. In 1990, Alexander R.

Apelado, Victozino E. Aclan and Noel A. Nival filed a petition for the recall of Evardone with the

Office of the Local Election Registrar, Municipality of Sulat. The Comelec issued a Resolution

approving the recommendation of Election Registrar Vedasto Sumbilla to hold the signing of

petition for recall against Evardone.Evardone filed a petition for prohibition with urgent prayer of

restraining order and/or writ of preliminary injunction. Later, in an en banc resolution, the

Comelec nullified the signing process for being violative of the TRO of the court. Hence, this

present petition.

Issue 1: WON Resolution No. 2272 promulgated by the COMELEC by virtue of its powers

under the Constitution and BP 337 (Local Government Code) was valid.

Held: Yes

Ratio: Evardone maintains that Article X, Section 3 of the 1987 Constitution repealed Batas

Pambansa Blg. 337 in favor of one to be enacted by Congress. Since there was, during the period

material to this case, no local government code enacted by Congress after the effectivity of the

1987 Constitution nor any law for that matter on the subject of recall of elected government

officials, Evardone contends that there is no basis for COMELEC Resolution No. 2272 and that

the recall proceedings in the case at bar is premature. The COMELEC avers that the constitutional

provision does not refer only to a local government code which is in futurum butalso in esse .

It merely sets forth the guidelines which Congress will consider in amending the provisions of the

present LGC. Pending the enactment of the amendatory law, the existing Local Government

Code remains operative. Article XVIII, Section 3 of the 1987 Constitution express provides that

all existing laws not inconsistent with the 1987Constitution shall remain operative, until amended,

repealed or revoked. Republic Act No. 7160 providing for the Local Government Code of 1991,

approved by the President on 10 October 1991, specifically repeals B.P. Blg. 337 as provided in

Sec. 534, Title Four of said Act .But the Local Government Code of 1991 will take effect only on

1 January 1992 and therefore the old Local Government Code (B.P. Blg.337) is still the law

5

applicable to the present case. Prior to the enactment of the new Local Government Code, the

effectiveness of B.P. Blg. 337 was expressly recognized in the proceedings of the 1986

Constitutional Commission. We therefore rule that Resolution No. 2272promulgated by the

COMELEC is valid and constitutional. Consequently, the COMELEC had the authority to

approve the petition for recall and set the date for the signing of said petition.

Issue 2: WON the TRO issued by this Court rendered nugatory the signing process of the

petition for recall held pursuant to Resolution No. 2272.

Held: No

Ratio: In the present case, the records show that Evardone knew of the Notice of Recall filed by

Apelado, on or about 21 February 1990 as evidenced by the Registry Return Receipt; yet, he was

not vigilant in following up and determining the outcome of such notice. Evardone alleges that it

was only on or about 3 July 1990 that he came to know about the Resolution of the COMELEC

setting the signing of the petition for recall on 14 July 1990. But despite his urgent prayer for the

issuance of a TRO, Evardone filed the petition for prohibition onlyon 10 July 1990. Indeed, this

Court issued a TRO on 12 July 1990 but the signing of the petition for recall took place just the

same on the scheduled date through no fault of the COMELEC and Apelado. The signing

process was undertaken by the constituents of the Municipality of Sulat and its Election Registrar

in good faith and without knowledge of the TRO earlier issued by this Court. As attested by

Election Registrar Sumbilla, about 2,050 of the 6,090 registered voters of Sulat, Eastern Samar or

about 34% signed the petition for recall. As held in Parades vs. Executive Secretary there is no

turning back the clock. The right to recall is complementary to the right to elect or appoint. It is

included in the right of suffrage. It is based on the theory that the electorate must maintain a direct

and elastic control over public functionaries. It is also predicated upon the idea that a public office

is "burdened" with public interests and that the representatives of the people holding public offices

are simply agents or servants of the people with definite powers and specific duties to perform and

to follow if they wish to remain in their respective offices. Whether or not the electorate of Sulat

has lost confidence in the incumbent mayor is a political question. It belongs to the realm

of politics where only the people are the judge. "Loss of confidence is the formal withdrawal by an

electorate of their trust in a person's ability to discharge his office previously bestowed on him by

the same electorate. The constituents have made a judgment and their will to recall Evardone has

already been ascertained and must be afforded the highest respect. Thus, the signing process held

last 14 July1990 for the recall of Mayor Felipe P. Evardone of said municipality is valid and has

legal effect. However, recall at this time is no longer possible because of the limitation provided in

Sec. 55 (2) of B.P. Blg, 337. The Constitution has mandated a synchronized national and local

election prior to 30 June 1992, or more specifically, as provided for in Article XVIII, Sec. 5 on the

second Monday of May, 1992. Thus, to hold an election on recall approximately seven (7)

months before the regular local election will be violative of the above provisions of the applicable

Local Government Code

VETERANS FEDERATION PARTY VS. COMELEC, digested

Posted by Pius Morados on November 9, 2011

342 SCRA 247, October 6, 2000 (Constitutional Law Party List

Representatives, 20% Allocation)

FACTS: Petitioner assailed public respondent COMELEC resolutions ordering

the proclamation of 38 additional party-list representatives to complete the 52

seats in the House of Representatives as provided by Sec 5, Art VI of the 1987

Constitution and RA 7941.

On the other hand, Public Respondent, together with the respondent parties,

avers that the filling up of the twenty percent membership of party-list

representatives in the House of Representatives, as provided under the

Constitution, was mandatory, wherein the twenty (20%) percent congressional

seats for party-list representatives is filled up at all times.

ISSUE: Whether or not the twenty percent allocation for party-list lawmakers is

mandatory.

HELD: No, it is merely a ceiling for the party-list seats in Congress. The same

declared therein a policy to promote proportional representation in the

election of party-list representatives in order to enable Filipinos belonging to

the marginalized and underrepresented sectors to contribute legislation that

would benefit them.

It however deemed it necessary to require parties, organizations and coalitions

participating in the system to obtain at least two percent of the total votes cast

for the party-list system in order to be entitled to a party-list seat. Those

garnering more than this percentage could have additional seats in proportion

to their total number of votes.

Furthermore, no winning party, organization or coalition can have more than

three seats in the House of Representatives (sec 11(b) RA 7941).

Note:

Clearly, the Constitution makes the number of district representatives the

determinant in arriving at the number of seats allocated for party-list

lawmakers, who shall comprise twenty per centum of the total number of

representatives including those under the party-list. We thus translate this

legal provision into a mathematical formula, as follows:

No. of district representatives

- x .20 = No. of party-list

.80 representatives

This formulation means that any increase in the number of district

representatives, as may be provided by law, will necessarily result in a

corresponding increase in the number of party-list seats. To illustrate,

considering that there were 208 district representatives to be elected during the

1998 national elections, the number of party-list seats would be 52, computed

as follows:

208

x .20 = 52

.80

6

The foregoing computation of seat allocation is easy enough to comprehend.

The problematic question, however, is this: Does the Constitution require all

such allocated seats to be filled up all the time and under all circumstances?

Our short answer is No.

G.R. No. 147589 June 26, 2001

ANG BAGONG BAYANI vs. Comelec

x---------------------------------------------------------x

G.R. No. 147613 June 26, 2001

BAYAN MUNA vs. Comelec

Facts

Petitioners challenged the Comelecs Omnibus Resolution No. 3785

,

which

approved the participation of 154 organizations and parties, including those

herein impleaded, in the 2001 party-list elections. Petitioners sought the

disqualification of private respondents, arguing mainly that the party-list system

was intended to benefit the marginalized and underrepresented; not the

mainstream political parties, the non-marginalized or

overrepresented. Unsatisfied with the pace by which Comelec acted on their

petition, petitioners elevated the issue to the Supreme Court.

Issue:

1. Whether or not petitioners recourse to the Court was proper.

2. Whether or not political parties may participate in the party list elections.

3. Whether or not the Comelec committed grave abuse of discretion in

promulgating Omnibus Resolution No. 3785.

Ruling:

1. The Court may take cognizance of an issue notwithstanding the availability of

other remedies "where the issue raised is one purely of law, where public

interest is involved, and in case of urgency." The facts attendant to the case

rendered it justiciable.

2. Political parties even the major ones -- may participate in the party-list

elections subject to the requirements laid down in the Constitution and RA

7941, which is the statutory law pertinent to the Party List System.

Under the Constitution and RA 7941, private respondents cannot be disqualified

from the party-list elections, merely on the ground that they are political parties.

Section 5, Article VI of the Constitution provides that members of the House of

Representatives may "be elected through a party-list system of registered

national, regional, and sectoral parties or organizations . It is however,

incumbent upon the Comelec to determine proportional representation of the

marginalized and underrepresented, the criteria for participation, in

relation to the cause of the party list applicants so as to avoid desecration of the

noble purpose of the party-list system.

3. The Court acknowledged that to determine the propriety of the inclusion of

respondents in the Omnibus Resolution No. 3785, a study of the factual

allegations was necessary which was beyond the pale of the Court. The Court

not being a trier of facts.

However, seeing that the Comelec failed to appreciate fully the clear policy of

the law and the Constitution, the Court decided to set some guidelines culled

from the law and the Constitution, to assist the Comelec in its work. The Court

ordered that the petition be remanded in the Comelec to determine compliance

by the party lists.

Summary of Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 82 S. Ct. 691, 7 L. Ed. 2d 663 (1962).

Facts

Charles Baker (P) was a resident of Shelby County, Tennessee. Baker filed suit

against Joe Carr, the Secretary of State of Tennessee. Bakers complaint alleged

that the Tennessee legislature had not redrawn its legislative districts since

1901, in violation of the Tennessee State Constitution which required

redistricting according to the federal census every 10 years. Baker, who lived in

an urban part of the state, asserted that the demographics of the state had

changed shifting a greater proportion of the population to the cities, thereby

diluting his vote in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Baker sought an injunction prohibiting further elections, and sought the remedy

of reapportionment or at-large elections. The district court denied relief on the

grounds that the issue of redistricting posed a political question and would

therefore not be heard by the court.

Issues

1. Do federal courts have jurisdiction to hear a constitutional challenge to a

legislative apportionment?

2. What is the test for resolving whether a case presents a political question?

Holding and Rule

1. Yes. Federal courts have jurisdiction to hear a constitutional challenge to a

legislative apportionment.

2. The factors to be considered by the court in determining whether a case

presents a political question are:

7

1. Is there a textually demonstrable constitutional commitment of the

issue to a coordinate political department (i.e. foreign affairs or

executive war powers)?

2. Is there a lack of judicially discoverable and manageable standards

for resolving the issue?

3. The impossibility of deciding the issue without an initial policy

determination of a kind clearly for nonjudicial discretion.

4. The impossibility of a courts undertaking independent resolution

without expressing lack of the respect due coordinate branches of

government.

5. Is there an unusual need for unquestioning adherence to a political

decision already made?

6. Would attempting to resolve the matter create the possibility of

embarrassment from multifarious pronouncements by various

departments on one question?

The political question doctrine is based in the separation of powers and whether

a case is justiciable is determined on a case by cases basis. In regards to foreign

relations, if there has been no conclusive governmental action regarding an

issue then a court can construe a treaty and decide a case. Regarding the dates

of the duration of hostilities, when there needs to be definable clarification for a

decision, the court may be able to decide the case.

The court held that this case was justiciable and did not present a political

question. The case did not present an issue to be decided by another branch of

the government. The court noted that judicial standards under the Equal

Protection Clause were well developed and familiar, and it had been open to

courts since the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment to determine if an act

is arbitrary and capricious and reflects no policy. When a question is enmeshed

with any of the other two branches of the government, it presents a political

question and the Court will not answer it without further clarification from the

other branches.

MARIANO, JR. VS. COMELEC, digested

Posted by Pius Morados on November 10, 2011

G.R. No. 118627; 242 SCRA 213, March 7, 1995 (Constitutional Law

Requirements in challenging the constitutionality of the law)

FACTS: Petitioners suing as tax payers, assail a provision (Sec 51) of RA No.

7859 (An Act Converting the Municipality of Makati Into a Highly Urbanized

City to be known as the City of Makati) on the ground that the same attempts to

alter or restart the 3-consecutive term limit for local elective officials

disregarding the terms previously served by them, which collides with the

Constitution (Sec 8, Art X & Sec 7, Art VI).

ISSUE: Whether or not challenge to the constitutionality of questioned law is

with merit.

HELD: No. The requirements before a litigant can challenge the

constitutionality of a law are well-delineated. They are: (1) there must be an

actual case or controversy; (2) the question of constitutionality must be raised

by the proper party; (3) the constitutional question must be raised at the earliest

possible opportunity; and (4) the decision on the constitutional question must be

necessary to the determination of the case itself.

The court cannot entertain this challenge to the constitutionality of section 51.

The requirements before a litigant can challenge the constitutionality of a law

are well delineated. They are: 1) there must be an actual case or controversy; (2)

the question of constitutionality must be raised by the proper party; (3) the

constitutional question must be raised at the earliest possible opportunity; and

(4) the decision on the constitutional question must be necessary to the

determination of the case itself.

Petitioners have far from complied with these requirements. The petition is

premised on the occurrence of many contingent events, i.e., that Mayor Binay

will run again in this coming mayoralty elections; that he would be re-elected in

said elections; and that he would seek re-election for the same position in the

1998 elections. Considering that these contingencies may or may not happen,

petitioners merely pose a hypothetical issue which has yet to ripen to an actual

case or controversy. Petitioners who are residents of Taguig (except Mariano)

are not also the proper parties to raise this abstract issue. Worse, they hoist this

futuristic issue in a petition for declaratory relief over which this Court has no

jurisdiction.

Montejo vs. COMELEC

242 SCRA 415

March 16, 1995

Facts:

Petitioner Cerilo Roy Montejo, representative of the first district of Leyte,

pleads for the annulment of Section 1 of Resolution no. 2736, redistricting

certain municipalities in Leyte, on the ground that it violates the principle of

equality of representation.

The province of Leyte with the cities of Tacloban and Ormoc is composed of 5

districts. The 3rd district is composed of: Almeria, Biliran, Cabucgayan,

Caibiran, Calubian, Culaba, Kawayan, Leyte, Maripipi, Naval, San Isidro,

Tabango and Villaba.

Biliran, located in the 3rd district of Leyte, was made its subprovince by virtue

of Republic Act No. 2141 Section 1 enacted on 1959. Said section spelled out

the municipalities comprising the subprovince: Almeria, Biliran, Cabucgayan,

8

Caibiran, Culaba, Kawayan, Maripipi and Naval and all the territories

comprised therein.

On 1992, the Local Government Code took effect and the subprovince of

Biliran became a regular province. (The conversion of Biliran into a regular

province was approved by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite.) As a

consequence of the conversion, eight municipalities of the 3rd district

composed the new province of Biliran. A further consequence was to reduce the

3rd district to five municipalities (underlined above) with a total population of

146,067 as per the 1990 census.

To remedy the resulting inequality in the distribution of inhabitants, voters and

municipalities in the province of Leyte, respondent COMELEC held

consultation meetings with the incumbent representatives of the province and

other interested parties and on December 29, 1994, it promulgated the assailed

resolution where, among others, it transferred the municipality of Capoocan of

the 2nd district and the municipality of Palompon of the 4th district to the 3rd

district of Leyte.

Issue:

Whether the unprecedented exercise by the COMELEC of the legislative power

of redistricting and reapportionment is valid or not.

Held:

Section 1 of Resolution no. 2736 is annulled and set aside.

The deliberations of the members of the Constitutional Commission shows that

COMELEC was denied the major power of legislative apportionment as it itself

exercised the power. Regarding the first elections after the enactment of the

1987 constitution, it is the Commission who did the reapportionment of the

legislative districts and for the subsequent elections, the power was given to the

Congress.

Also, respondent COMELEC relied on the ordinance appended to the 1987

constitution as the source of its power of redistricting which is traditionally

regarded as part of the power to make laws. Said ordinance states that:

Section 2: The Commission on Elections is hereby empowered to make minor

adjustments to the reapportionment herein made.

Section 3 : Any province that may hereafter be createdThe number of

Members apportioned to the province out of which such new province was

created or where the city, whose population has so increases, is geographically

located shall be correspondingly adjusted by the Commission on Elections but

such adjustment shall not be made within one hundred and twenty days before

the election.

Minor adjustments does not involve change in the allocations per district.

Examples include error in the correct name of a particular municipality or when

a municipality in between which is still in the territory of one assigned district is

forgotten. And consistent with the limits of its power to make minor

adjustments, section 3 of the Ordinance did not also give the respondent

COMELEC any authority to transfer municipalities from one legislative district

to another district. The power granted by section 3 to the respondent is to adjust

the number of members (not municipalities.)

Romualdez-Marcos vs. COMELEC

CI TATI ON: 248 SCRA 300

FACTS:

Imelda, a little over 8 years old, in or about 1938, established her domicile in

Tacloban, Leyte where she studied and graduated high school in the Holy Infant

Academy from 1938 to 1949. She then pursued her college degree, education,

in St. Pauls College now Divine Word University also in

Tacloban. Subsequently, she taught in Leyte Chinese School still in

Tacloban. She went to manila during 1952 to work with her cousin, the late

speaker Daniel Romualdez in his office in the House of Representatives. In

1954, she married late President Ferdinand Marcos when he was still a

Congressman of Ilocos Norte and was registered there as a voter. When Pres.

Marcos was elected as Senator in 1959, they lived together in San Juan, Rizal

where she registered as a voter. In 1965, when Marcos won presidency, they

lived in Malacanang Palace and registered as a voter in San Miguel

Manila. She served as member of the Batasang Pambansa and Governor of

Metro Manila during 1978.

Imelda Romualdez-Marcos was running for the position of Representative of

the First District of Leyte for the 1995 Elections. Cirilo Roy Montejo, the

incumbent Representative of the First District of Leyte and also a candidate for

the same position, filed a Petition for Cancellation and Disqualification"

with

the Commission on Elections alleging that petitioner did not meet the

constitutional requirement for residency. The petitioner, in an honest

misrepresentation, wrote seven months under residency, which she sought to

9

rectify by adding the words "since childhood" in her Amended/Corrected

Certificate of Candidacy filed on March 29, 1995 and that "she has always

maintained Tacloban City as her domicile or residence. She arrived at the seven

months residency due to the fact that she became a resident of the Municipality

of Tolosa in said months.

ISSUE: Whether petitioner has satisfied the 1year residency requirement to be

eligible in running as representative of the First District of Leyte.

HELD:

Residence is used synonymously with domicile for election purposes. The

court are in favor of a conclusion supporting petitoners claim of legal residence

or domicile in the First District of Leyte despite her own declaration of 7

months residency in the district for the following reasons:

1. A minor follows domicile of her parents. Tacloban became Imeldas

domicile of origin by operation of law when her father brought them to Leyte;

2. Domicile of origin is only lost when there is actual removal or change of

domicile, a bona fide intention of abandoning the former residence and

establishing a new one, and acts which correspond with the purpose. In the

absence and concurrence of all these, domicile of origin should be deemed to

continue.

3. A wife does not automatically gain the husbands domicile because the term

residence in Civil Law does not mean the same thing in Political Law. When

Imelda married late President Marcos in 1954, she kept her domicile of origin

and merely gained a new home and not domicilium necessarium.

4. Assuming that Imelda gained a new domicile after her marriage and acquired

right to choose a new one only after the death of Pres. Marcos, her actions upon

returning to the country clearly indicated that she chose Tacloban, her domicile

of origin, as her domicile of choice. To add, petitioner even obtained her

residence certificate in 1992 in Tacloban, Leyte while living in her brothers

house, an act, which supports the domiciliary intention clearly manifested. She

even kept close ties by establishing residences in Tacloban, celebrating her

birthdays and other important milestones.

WHEREFORE, having determined that petitioner possesses the necessary

residence qualifications to run for a seat in the House of Representatives in the

First District of Leyte, the COMELEC's questioned Resolutions dated April 24,

May 7, May 11, and May 25, 1995 are hereby SET ASIDE. Respondent

COMELEC is hereby directed to order the Provincial Board of Canvassers to

proclaim petitioner as the duly elected Representative of the First District of

Leyte.

issue: whether or not petitioner lost her domicile of origin by operation of law

as a result of her marriage to the late president Marcos.

held: For election purposes, residence i s used synonymously with

domicile. the court upheld the qualification of petitioner, despite her own

declaration in her certificate of candidacy that she had resided in the district for

only 4 months, because of the followiing (a) a minor follows the domicile of her

parents: tacloban became petitioner1s domicile of origin by operation of law

when her father brought the family toLeyte; (b) domicile of origin is lost only

'hen there is actual removal or change of domicile, a bona fide intention of

abandoning the former residence and establishing a new one, and acts which

correspond with the purpose; i n the absence of clear and positive

proof of the concurrence of all these, the domicile of origi n should

be deemed to continue; (c) the wife does not automatically gain the

husbands domicile because the term residence in civil Law does not mean

the same thing in political Law; when petitioner married president Marcos in

1954, she kept her domicile of origin and merely gained a new home, not

adomicilium necessarium; (d) even assuming that she gained a new

domicile after her marriage and acquired the right to choose a new one

only after her husband died, her acts following her return to the country clearly

indicate that she chose tacloban, her domicile of origin, as her domicile of

choice.

Aquino v. comelec

62 SCRA 275 Political Law De Jure vs De Facto Government Marcos as

a De Jure President Under the 1973 Constitution

In January 1975, a petition for prohibition was filed to seek the nullification of

some Presidential Decrees issued by then President Ferdinand Marcos. It was

alleged that Marcos does not hold any legal office nor possess any lawful

authority under either the 1935 Constitution or the 1973 Constitution and

therefore has no authority to issue the questioned proclamations, decrees and

orders.

ISSUE: Whether or not the Marcos government is a lawful government.

HELD: Yes. First of, this is actually a quo warranto proceedings and Benigno

Aquino, Jr. et al, have no legal personality to sue because they have no claim to

the office of the president. Only the Solicitor General or the person who asserts

title to the same office can legally file such a quo warranto petition.

On the issue at bar, the Supreme Court affirmed the validity of Martial Law

Proclamation No. 1081 issued on September 22, 1972 by President Marcos

because there was no arbitrariness in the issuance of said proclamation pursuant

10

to the 1935 Constitution; that the factual bases (the circumstances of

lawlessness then present) had not disappeared but had even been exacerbated;

that the question as to the validity of the Martial Law proclamation has been

foreclosed by Section 3(2) of Article XVII of the 1973 Constitution.

Under the (1973) Constitution, the President, if he so desires; can continue in

office beyond 1973. While his term of office under the 1935 Constitution

should have terminated on December 30, 1973, by the general referendum of

July 27-28, 1973, the sovereign people expressly authorized him to continue in

office even beyond 1973 under the 1973 Constitution (which was validly

ratified on January 17, 1973 by the sovereign people) in order to finish the

reforms he initiated under Martial Law; and as aforestated, as this was the

decision of the people, in whom sovereignty resides . . . and all government

authority emanates . . ., it is therefore beyond the scope of judicial inquiry. The

logical consequence therefore is that President Marcos is ade jure President of

the Republic of the Philippines.

BENGSON vs. HRET and CRUZ

G.R. No. 142840

May 7, 2001

FACTS: The citizenship of respondent Cruz is at issue in this case, in view of

the constitutional requirement that no person shall be a Member of the House

of Representatives unless he is a natural-born citizen.

Cruz was a natural-born citizen of the Philippines. He was born in Tarlac in

1960 of Filipino parents. In 1985, however, Cruz enlisted in the US Marine

Corps and without the consent of the Republic of the Philippines, took an oath

of allegiance to the USA. As a Consequence, he lost his Filipino citizenship for

under CA No. 63 [(An Act Providing for the Ways in Which Philippine

Citizenship May Be Lost or Reacquired (1936)] section 1(4), a Filipino citizen

may lose his citizenship by, among other, rendering service to or accepting

commission in the armed forces of a foreign country.

Whatever doubt that remained regarding his loss of Philippine citizenship was

erased by his naturalization as a U.S. citizen in 1990, in connection with his

service in the U.S. Marine Corps.

In 1994, Cruz reacquired his Philippine citizenship through repatriation under

RA 2630 [(An Act Providing for Reacquisition of Philippine Citizenship by

Persons Who Lost Such Citizenship by Rendering Service To, or Accepting

Commission In, the Armed Forces of the United States (1960)]. He ran for and

was elected as the Representative of the 2nd District of Pangasinan in the 1998

elections. He won over petitioner Bengson who was then running for reelection.

Subsequently, petitioner filed a case for Quo Warranto Ad Cautelam with

respondent HRET claiming that Cruz was not qualified to become a member of

the HOR since he is not a natural-born citizen as required under Article VI,

section 6 of the Constitution.

HRET rendered its decision dismissing the petition for quo warranto and

declaring Cruz the duly elected Representative in the said election.

ISSUE: WON Cruz, a natural-born Filipino who became an American citizen,

can still be considered a natural-born Filipino upon his reacquisition of

Philippine citizenship.

HELD: petition dismissed

YES

Filipino citizens who have lost their citizenship may however reacquire the

same in the manner provided by law. C.A. No. 63 enumerates the 3 modes by

which Philippine citizenship may be reacquired by a former citizen:

1. by naturalization,

2. by repatriation, and

3. by direct act of Congress.

**

Repatriation may be had under various statutes by those who lost their

citizenship due to:

1. desertion of the armed forces;

2. services in the armed forces of the allied forces in World War II;

3. service in the Armed Forces of the United States at any other time,

4. marriage of a Filipino woman to an alien; and

5. political economic necessity

Repatriation results in the recovery of the original nationality This means that a

naturalized Filipino who lost his citizenship will be restored to his prior status

as a naturalized Filipino citizen. On the other hand, if he was originally a

natural-born citizen before he lost his Philippine citizenship, he will be restored

to his former status as a natural-born Filipino.

R.A. No. 2630 provides:

Sec 1. Any person who had lost his Philippine citizenship by rendering service

to, or accepting commission in, the Armed Forces of the United States, or after

separation from the Armed Forces of the United States, acquired United States

citizenship, may reacquire Philippine citizenship by taking an oath of allegiance

to the Republic of the Philippines and registering the same with Local Civil

Registry in the place where he resides or last resided in the Philippines. The

said oath of allegiance shall contain a renunciation of any other citizenship.

Having thus taken the required oath of allegiance to the Republic and having

registered the same in the Civil Registry of Magantarem, Pangasinan in

accordance with the aforecited provision, Cruz is deemed to have recovered his

original status as a natural-born citizen, a status which he acquired at birth as

the son of a Filipino father. It bears stressing that the act of repatriation allows

him to recover, or return to, his original status before he lost his Philippine

citizenship.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- NEW Handbook On Debt RecoveryDocument173 pagesNEW Handbook On Debt RecoveryRAJALAKSHMI HARIHARAN100% (5)

- Bill of Rights ReviewerDocument12 pagesBill of Rights Revieweriyangtot100% (7)

- B3 PDFDocument465 pagesB3 PDFabdulramani mbwana100% (7)

- StuntsDocument7 pagesStuntsiyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- Technical and Financial Proposal - Cloud Computing Hosting ServiceDocument5 pagesTechnical and Financial Proposal - Cloud Computing Hosting Serviceissa galalPas encore d'évaluation

- RP FinalDocument125 pagesRP FinalAditya SoumavaPas encore d'évaluation

- Santiago v. COMELEC Case DigestDocument5 pagesSantiago v. COMELEC Case Digestrachel cayangaoPas encore d'évaluation

- 4th Presentation ETHICS Module 7 and 8Document22 pages4th Presentation ETHICS Module 7 and 8Samuel Allen L. GelacioPas encore d'évaluation

- Xvi. Amendments or RevisionsDocument17 pagesXvi. Amendments or RevisionsAminaamin GuroPas encore d'évaluation

- Statutory ConstructionDocument9 pagesStatutory ConstructionJC HilarioPas encore d'évaluation

- 1987 Constitution: February 2, 1987Document518 pages1987 Constitution: February 2, 1987Jing Goal Merit100% (1)

- Philippine Constitution IntroductionDocument35 pagesPhilippine Constitution IntroductionRanay, Rachel Anne100% (1)

- DIWA PartylistDocument5 pagesDIWA PartylistJohn Lester TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Article VII - Executive - SummaryDocument11 pagesArticle VII - Executive - SummaryRyan JubeePas encore d'évaluation

- Synopsis (Article1156 1230)Document13 pagesSynopsis (Article1156 1230)Julius AmontosPas encore d'évaluation

- Masikip v. City of Pasig, G.R. No. 136349, January 23, 2006Document12 pagesMasikip v. City of Pasig, G.R. No. 136349, January 23, 2006FD BalitaPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER THREE: Aids To Construction: Ebarle v. SucalditoDocument18 pagesCHAPTER THREE: Aids To Construction: Ebarle v. SucalditoKatPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti - Fabella v. CADocument2 pagesConsti - Fabella v. CAIrish GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION - Course Outline and DefinitionsDocument32 pagesSTATUTORY CONSTRUCTION - Course Outline and DefinitionsEdgar Calzita AlotaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurisdiction of CourtsDocument9 pagesJurisdiction of CourtsisteypaniflorPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Philippine ConstitutionsDocument4 pagesHistory of Philippine ConstitutionsAngie Abellon100% (1)

- All AreasDocument648 pagesAll AreasGladys Morada100% (1)

- Torres V Comelec, 270 SCRA 583Document3 pagesTorres V Comelec, 270 SCRA 583ambotnimoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lambino Vs ComelecDocument38 pagesLambino Vs ComelecGerard CalderonPas encore d'évaluation

- Importance of Research On Our Daily LivesDocument1 pageImportance of Research On Our Daily LivesDanny De LeonPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Political LawDocument38 pagesIntroduction To Political LawJenny AbilleroPas encore d'évaluation

- Legislative Department, ContilawDocument98 pagesLegislative Department, ContilawI'em Wagas100% (1)

- The ConstitutionDocument168 pagesThe ConstitutionOscar Ryan SantillanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cass Vs Snow Brothers1Document4 pagesCass Vs Snow Brothers1frankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 - The Concept of The State Chapter 1 - General ConsiderationsDocument9 pagesChapter 3 - The Concept of The State Chapter 1 - General ConsiderationsJosine ProtasioPas encore d'évaluation

- Calalang V Williams PDFDocument4 pagesCalalang V Williams PDFPrincess Loyola TapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Family Code of The PhilippinesDocument14 pagesFamily Code of The PhilippinesYvette TevesPas encore d'évaluation

- Infographic PDFDocument1 pageInfographic PDFMarbert Dy NuñezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Rules of Statutory ConstructionDocument2 pagesBasic Rules of Statutory ConstructionRi bearPas encore d'évaluation

- Share 1589175960727 Notes Statutory Construction A CompendiumDocument50 pagesShare 1589175960727 Notes Statutory Construction A CompendiumJuly TadePas encore d'évaluation

- Anti Wire Tapping Case DigestDocument7 pagesAnti Wire Tapping Case Digestcrystine jaye senadrePas encore d'évaluation

- Imperium (B) Constitutional Law (C) State (D) ArchipelagoDocument7 pagesImperium (B) Constitutional Law (C) State (D) ArchipelagoRob3rtJohnsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Ferdinand E. Marcos vs. Hon. Raul Manglapus (177 Scra 668) Case DigestDocument1 pageFerdinand E. Marcos vs. Hon. Raul Manglapus (177 Scra 668) Case DigestDayday AblePas encore d'évaluation

- 6 G.R. No. L-22301Document2 pages6 G.R. No. L-22301Jessel MaglintePas encore d'évaluation

- Senate Blue Ribbon Vs MajaduconDocument7 pagesSenate Blue Ribbon Vs MajaduconSamantha LawrencePas encore d'évaluation

- Digests 1Document54 pagesDigests 1Mikko MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Bill of Rights Lecture NotesDocument7 pagesPhilippine Bill of Rights Lecture NotesDave UmeranPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digests On The SyllabusDocument1 pageCase Digests On The SyllabusCleofe SobiacoPas encore d'évaluation

- Brunei Second OutputDocument3 pagesBrunei Second Outputzasa1234aPas encore d'évaluation

- The 1987 Constitution of The Republic of The Philippines: PreambleDocument13 pagesThe 1987 Constitution of The Republic of The Philippines: PreambleIssa JavelosaPas encore d'évaluation

- CSCDocument23 pagesCSCIsaias S. Pastrana Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Polirev ReviewerDocument30 pagesPolirev ReviewerNas Laarnie NasamPas encore d'évaluation

- Inquiry in Aid of Legislation - AchacosoDocument6 pagesInquiry in Aid of Legislation - AchacosoNeil AchacosoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2018 PoliticalLaw PreWeek PDFDocument99 pages2018 PoliticalLaw PreWeek PDFAicaPascualPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 C Philo Midterms ReviewerDocument31 pages1 C Philo Midterms ReviewerNicole PTPas encore d'évaluation

- Abacan vs. Northwestern UniversityDocument10 pagesAbacan vs. Northwestern UniversityRalph VelosoPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Sangguniang KabataanDocument4 pagesHistory of Sangguniang KabataanMarjorie ManaloPas encore d'évaluation

- 96.padlan v. Sps - Dinglasan, G.R. No. 180321Document8 pages96.padlan v. Sps - Dinglasan, G.R. No. 180321royalwhoPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 2 Answer KeyDocument2 pagesAssignment 2 Answer KeyAbdulakbar Ganzon BrigolePas encore d'évaluation

- Batangas Catv vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 138810, September 29, 2004Document9 pagesBatangas Catv vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 138810, September 29, 2004FD BalitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti Law 1 Syllabus PDFDocument59 pagesConsti Law 1 Syllabus PDFverlyn ocretoPas encore d'évaluation

- Barangay Profiling Forms Collecting ToolDocument12 pagesBarangay Profiling Forms Collecting ToolMerché Florendo BrofasPas encore d'évaluation

- Disbarment - Legal and JudicialDocument1 pageDisbarment - Legal and JudicialAdam Cuenca100% (1)

- Final Examination in Statutory ConstructionDocument1 pageFinal Examination in Statutory ConstructionRichard C. AmoguisPas encore d'évaluation

- FAR EAST CORPORATION VS AIRTROPOLIS CONSOLIDATORS PHILIPPINES - Full TextDocument9 pagesFAR EAST CORPORATION VS AIRTROPOLIS CONSOLIDATORS PHILIPPINES - Full TextSam LeynesPas encore d'évaluation

- 72 Scra 520 Bocobo Vs Estanislao G.R. No. L-30458 August 31, 1976Document2 pages72 Scra 520 Bocobo Vs Estanislao G.R. No. L-30458 August 31, 1976Jun Rinon100% (1)

- Case Digest - G.R No. 119673Document1 pageCase Digest - G.R No. 119673Selynn CoPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Mandaluyong - Rules of Procedure of The Sangguniang PanlungsodDocument19 pagesCity of Mandaluyong - Rules of Procedure of The Sangguniang PanlungsodAnonymous iBVKp5Yl9APas encore d'évaluation

- ConstitutionDocument17 pagesConstitutionJomel Serra BrionesPas encore d'évaluation

- 66 Defensor - Santiago vs. COMELECDocument20 pages66 Defensor - Santiago vs. COMELECFrechie Carl TampusPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti CaseDocument52 pagesConsti CaseTania FrenchPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Names: Centaurium ErythraeaDocument1 pageCommon Names: Centaurium ErythraeaiyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- Simple Squamous Epithelium Simple Columnar EpitheliumDocument3 pagesSimple Squamous Epithelium Simple Columnar EpitheliumiyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Philippine ConstitutionsDocument7 pagesHistory of Philippine Constitutionsjackieferdie89% (47)

- GR No. 137873 April 20, 2001 Consunji vs. Court of Appeals Facts: RulingDocument12 pagesGR No. 137873 April 20, 2001 Consunji vs. Court of Appeals Facts: RulingiyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Dental Caries?Document4 pagesWhat Is Dental Caries?iyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- Stat DigestDocument3 pagesStat DigestiyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- Rodolfo C. Pacampara For Petitioners. Tito M. Villaluna For RespondentsDocument15 pagesRodolfo C. Pacampara For Petitioners. Tito M. Villaluna For RespondentsiyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal ResearchDocument25 pagesLegal ResearchiyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal ResearchDocument25 pagesLegal ResearchiyangtotPas encore d'évaluation

- Plant HR Business Partner in Chicago IL Resume David AndreDocument2 pagesPlant HR Business Partner in Chicago IL Resume David AndreDavidAndrePas encore d'évaluation

- College Online Applicant Profile SheetDocument2 pagesCollege Online Applicant Profile SheetRuvie Grace HerbiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Assistant Sub Inspector (BS-09) Anti Corruption Establishment Punjab 16 C 2020 PDFDocument3 pagesAssistant Sub Inspector (BS-09) Anti Corruption Establishment Punjab 16 C 2020 PDFAgha Khan DurraniPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Examinations Labor LawDocument1 pageFinal Examinations Labor LawAtty. Kristina de VeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus For Persons and Family Relations 2019 PDFDocument6 pagesSyllabus For Persons and Family Relations 2019 PDFLara Michelle Sanday BinudinPas encore d'évaluation

- FI Market Research TemplateDocument3 pagesFI Market Research TemplateAnonymous DCxx70Pas encore d'évaluation

- Close Reading Practice Sherman Alexies Superman and MeDocument4 pagesClose Reading Practice Sherman Alexies Superman and Meapi-359644173Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2024 01135 People of The State of V People of The State of Copy of Notice of A 1Document18 pages2024 01135 People of The State of V People of The State of Copy of Notice of A 1Aaron ParnasPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2Document30 pagesModule 2RarajPas encore d'évaluation

- Kashmir DisputeDocument13 pagesKashmir DisputeAmmar ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- K.E.E.I. Notes - Fall 2010Document8 pagesK.E.E.I. Notes - Fall 2010Kijana Educational Empowerment InitiativePas encore d'évaluation

- Court of Appeals Order AffirmingDocument16 pagesCourt of Appeals Order AffirmingLisa AutryPas encore d'évaluation

- Glo 20is 2017 PDFDocument317 pagesGlo 20is 2017 PDFKristine LlamasPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporaries of ChaucerDocument3 pagesContemporaries of ChaucerGarret RajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Accessing Resources For Growth From External SourcesDocument14 pagesAccessing Resources For Growth From External SourcesHamza AdilPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit - I: Section - ADocument22 pagesUnit - I: Section - AskirubaarunPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of Science and Technology in The PhilippinesDocument12 pagesDevelopment of Science and Technology in The PhilippinesJyra Shael L. EscanerPas encore d'évaluation

- 202 CẶP ĐỒNG NGHĨA TRONG TOEICDocument8 pages202 CẶP ĐỒNG NGHĨA TRONG TOEICKim QuyênPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Term Paper Guidelines T4 2022 1Document2 pagesMarketing Term Paper Guidelines T4 2022 1Chad OngPas encore d'évaluation

- CCES Guide 2018Document117 pagesCCES Guide 2018Jonathan RobinsonPas encore d'évaluation

- BTL VĨ Mô Chuyên SâuDocument3 pagesBTL VĨ Mô Chuyên SâuHuyền LinhPas encore d'évaluation

- LESSON 1-3 HistoryDocument13 pagesLESSON 1-3 HistoryFLORIVEN MONTELLANOPas encore d'évaluation

- Solidcam Glodanje Vjezbe Ivo SladeDocument118 pagesSolidcam Glodanje Vjezbe Ivo SladeGoran BertoPas encore d'évaluation

- IFF CAGNY 2018 PresentationDocument40 pagesIFF CAGNY 2018 PresentationAla BasterPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of Probable Cause: ArresteeDocument3 pagesAffidavit of Probable Cause: ArresteeMcKenzie StaufferPas encore d'évaluation

- School Calendar Version 2Document1 pageSchool Calendar Version 2scituatemarinerPas encore d'évaluation