Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

11

Transféré par

kochikaghochi0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

15 vues12 pagesvbsfg

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentvbsfg

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

15 vues12 pages11

Transféré par

kochikaghochivbsfg

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 12

Periodontology 2000, Vol.

29, 2002, 223234 Copyright C Blackwell Munksgaard 2002

Printed in Denmark. All rights reserved

PERIODONTOLOGY 2000

ISSN 0906-6713

The economics of periodontal

diseases

L. JncxsoN BnowN, BrvrnIv A. JonNs & Tnorns P. WnII

Periodontal diseases affect people all over the world.

They are among the endemic human diseases of our

planet. All cultures exhibit some form and distri-

bution of these diseases. Diet, genetics, personal oral

hygiene, social customs, group (public) preventive

services, as well as personal dental preventive, diag-

nostic, and therapeutic services all inuence the ex-

tent, severity and course of these diseases (12). It is

known that some systemic diseases can complicate

periodontal diseases. Recently, some research has

suggested that the reverse may also be true (16, 18,

2325, 27, 28, 33, 36, 41, 42).

The economic afuence of nations, their techno-

logical development, as well as the availability and

preparation of dental personnel, limit and shape the

scope of preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic

management of periodontal diseases. Thus, the eco-

nomics of periodontal diseases are fundamentally

different between afuent and poor countries. Less

afuent countries have fewer resources to use for all

human needs and wants, including management of

dental diseases. For poorer countries, periodontal

services are typically rudimentary. Management of

these diseases by trained personnel is rare, and in

some cases, almost nonexistent. As pointed out by

Neely, Le et al. (30, 31, 35), the course of peri-

odontal diseases in countries with little professional

preventive or therapeutic intervention may be view-

ed as a natural history of these diseases. In contrast,

the course of these diseases in technologically ad-

vanced countries is more aptly viewed as a clinical

course because of the presence of professional inter-

vention.

As risk and predisposing factors vary among the

peoples of the world, they may explain a good part

of the variation in the character and presentation of

periodontal diseases in different countries (2). There

remains, of course, enormous variation among indi-

viduals within countries and this variation also is ex-

223

plained by many of the same factors, modulated by

the host response of individuals.

Data on the economics of the periodontal diseases

in most countries are scarce. For many nations, the

national accounting and data collection systems are

not developed enough to provide broad and reliable

information. For technologically advanced coun-

tries, more data are available to sketch the economic

dimensions of periodontal disease. The United

States, in particular, has substantial data with which

to describe the extent of periodontal diseases found

in the population; the amount and type of peri-

odontal services provided; and the number and

characteristics of those who provide the services.

The remainder of this chapter uses the United

States as a case study for afuent countries. Much of

the information will be generally applicable to other

industrialized countries. Nevertheless, even among

afuent countries, one would expect national differ-

ences due to political, cultural, dietary, health deliv-

ery and individual diversity. The undeveloped coun-

tries of the world present a very different model of

the economics of periodontal disease which will be

addressed in the concluding sections.

Potential market for periodontal

services

The potential market for periodontal services is de-

termined by three primary factors: (i) the size of the

population, (ii) the extent and severity of periodontal

diseases within that population, and (iii) the scien-

tically efcacious means to treat or prevent these

diseases. These factors interact to create need for

care.

Brown et al.

U.S. population trends

U.S. population estimates by age for 1980 and 1990,

along with projections for 2000, 2010 and 2020 are

presented in Table1. These data provides us with a

review of the last 20years and a preview of what may

happen during the next 20years. The total popula-

tion has increased by about 50 million since 1980

and is expected to grow by another 50 million by

2020.

Most periodontal diseases affect adults. As will be

described later, the two age groups with the highest

utilization of periodontal services are those 4554

years old and 5564years old. The 4554 age group

has already experienced substantial growth since

1980, especially during the past 10years.

The 4554 age cohort will grow through 2010 and

then decline. The 5564 age cohort will experience

signicant growth during the next 20 years. Another

age group with a somewhat lower utilization, but

high disease, is the 65 and older age group. They will

grow by more than 50% between 2000 and 2020. This

increase along with any future changes in the behav-

ior of this elderly group (e.g. keeping more of their

teeth and/or working longer) may have a large im-

pact on the demand for periodontal services.

Epidemiology of periodontal diseases

The capacity to make longitudinal comparisons on

the extent and severity of periodontal diseases in the

United States is limited by changes in methodology

that have been used to measure these diseases in

nationally representative epidemiological surveys.

The two major national surveys available are the

First National Health and Nutrition Examination

Survey (34) (NHANES I) conducted between 1971

Table1. US residential population (in thousands)

Age 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

25 93,777 90,910 96,969 102,264 106,744

25-34 37,082 43,174 37,441 38,851 42,794

35-44 25,634 37,444 44,894 39,443 40,711

45-54 22,800 25,062 37,166 44,161 38,838

55-64 21,703 21,116 24,001 35,429 42,108

65 25,550 31,084 34,837 39,715 53,734

Total 226,546 248,790 275,308 299,863 324,929

Source: US bureau of census.

224

and 1974 and the Third National Health and Nu-

trition Examination Survey (45) (NHANES III) con-

ducted between 1988 and 1994. The earlier survey

used Russells Periodontal Index (40). With that

index, each tooth is visually assessed for gingivitis

and periodontitis. Gingival assessment is based on

the extent of inammation around a tooth. Severity,

as indicated by the degree of inammation at a site,

is not scored and the site around the tooth where

the defect is located is not identied. In contrast,

NHANES III included separate measurements of gin-

givitis and periodontitis. Bleeding on gentle probing

was used to indicate the presence of gingivitis (29).

Clinical attachment level was measured indirectly

from recession and pocket depth, which was meas-

ured linearly at specic sites around the teeth (3, 21).

Thus, trends will not be presented; rather the extent

and severity of gingivitis and periodontitis from

NHANES III will be reported.

Gingivitis

Using NHANES III data, Albandar and Kingman esti-

mated that approximately 54% of all U.S. adults ages

30years or older had gingivitis in the early 1990s (4).

Males had a slightly higher prevalence of gingival

bleeding than females. Mexican-Americans had a

higher prevalence than Non-Hispanic Blacks; Non-

Hispanic Whites had the lowest prevalence. Fifteen

percent of teeth demonstrated bleeding gingival at

some gingival site. Prevalence increased slightly with

age, reaching 60% in persons 70years and older.

Albandar & Kingman classied gingivitis by the ex-

tent of teeth with bleeding. Limited gingivitis in-

volved 24 teeth or 2550% of teeth examined. Ex-

tensive gingivitis involved 5 or more teeth or 50%

Table2. Percent and number of individuals (1000s)

by gingival status and age

Age Extensive Limited

Gingivitis Gingivitis

Percent Number Percent Number

35-39 11.03 2,027 20.46 3,760

45-49 8.00 903 22.94 2,592

55-59 10.40 788 23.18 1,799

65-69 14.48 838 20.18 1,357

75-79 17.58 432 23.22 998

All 10.50 10,900 21.80 22,613

Source: Albandar JM, Kingman A (4).

The economics of periodontal diseases

of teeth. Using these classications, 32% of U.S.

adults (over 33 million persons) aged 30years old

exhibited either limited or extensive gingivitis; 10.5%

(about 10.9 million persons) had extensive gingival

inammation; 21.8% (about 22.6 million persons)

had limited gingival involvement; and 67.7% of

adults were without an appreciable extent of gingi-

vitis. There was not a marked increase in the extent

of the disease with age. Males had somewhat more

extensive gingivitis than females.

Periodontitis

Albandar et al. classied mild periodontitis as one or

more teeth with 3mm probing depth and attach-

ment loss, or one or more posterior teeth with a

grade I furcation involvement (3, 44). They classied

moderate periodontitis as one or more teeth with 5

mm probing depth and attachment loss or two or

more teeth (30% of teeth examined) with 4mm

probing depth and attachment loss. Advanced peri-

odontitis involves two or more teeth (30% or more

of teeth examined) with 5mm probing depth and

attachment loss, or four or more teeth (60% of

teeth examined) with 4mm probing depth and

attachment loss, or one or more posterior teeth with

grade II furcation involvement. Moderate and ad-

vanced cases, especially those with furcation in-

volvement, are likely to require therapy and manage-

ment by a periodontist.

About 3.1% of adults 30years or older in the

United States were classied with advanced peri-

odontitis. See Table3. This represents about 3.2 mil-

lion persons. Moderate periodontitis was found in

9.5% of adults, totaling 9.9 millions persons. Another

21.8%, representing 22.6 million persons, exhibited

Table 3. Percent and number of individuals (1000s) with periodontitis by severity and age

Mean Tooth

Age Advanced Moderate Mild Loss

Percent Number Percent Number Percent Number Number

35-39 2.28 418 7.25 1330 16.65 3054 2.55

45-49 3.84 433 11.04 1247 22.10 2495 4.82

55-59 3.91 293 14.46 1082 28.22 2113 7.61

65-69 5.90 341 15.18 878 33.03 1910 8.18

75-79 3.32 81 19.92 487 29.52 722 11.02

All 3.10 3228 9.5 9874 21.80 22.620 4.76

Source: Albandar JM, Kingman A (4).

225

mild periodontitis. The percentage of adults with any

periodontitis (mild, moderate, or advanced) in-

creased with age to around 70years, and then leveled

off. This may have been the result of increasing loss

of teeth among this group. The prevalence and se-

verity of periodontitis were higher in males than fe-

males and higher in blacks and Mexican Americans

than in whites.

Need for periodontal services

From the population and epidemiologic data, it is

apparent that millions of people in the United States

have clinical signs of previous or current periodontal

disease. Also, the population at highest risk of these

diseases has increased during the past 20years and

is predicted to continue increasing for the next 20

years.

One approach to developing an estimate of the

potential market for periodontal services uses demo-

graphic and epidemiologic information to develop

an assessment of need for periodontal services. The

presence of clinical signs of tissue damage resulting

from past or current periodontal disease only sug-

gests a possible need for care. In addition, need as-

sessment requires a normative judgment as to the

amount and kind of services required by an individ-

ual in order to attain or maintain some level of

health. Oliver et al. provide a thorough discussion of

periodontal treatment needs as well as a review of

studies that estimated periodontal treatment needs

(39, 44).

Need for care generally arises because of the exist-

ence of untreated disease. In addition, the scientic

basis for efcacious therapy must exist. In afuent

societies, untreated disease in some population sub-

Brown et al.

groups usually coexists with the majority of the

population receiving the highest quality of care. In

less afuence societies, a preponderance of disease

may go without therapeutic intervention.

Using epidemiologic data from the 1985 National

Institute of Dental Research (NIDR) Survey of Em-

ployed Adults (32, 44), Oliver et al. developed an esti-

mate of hours of periodontal care needed annually

in the United States (38). They estimated that 13.5

26.2 million hours of scaling and surgery were

needed and that about 11.5 million hours of those

services were provided. They also estimated that

about 100 million hours of prophylaxes were needed

and 92 million hours were provided. If these esti-

mates are reasonably accurate, they suggest that the

size of the potential market for periodontal services

is considerable, and also that much, but not all, of

the periodontal services needed were being provided

in the middle 1980s. In a subsequent study, Oliver et

al. suggested that treatment needs may have been

declining over time from the 1970s through the mid-

1980s (37).

It should be noted that estimates of the potential

size of the market for periodontal services are based

on assumptions and data that may change over time.

Estimates are also dependent on the methods used

and provide only general guides to the extent of need

in a population. In fact, several conditions have

changed since the mid-1980s. The size of the popu-

lation at highest risk for periodontal disease has in-

creased and will continue to do so. Scientic ad-

vances have resulted in changes to treatment proto-

cols. Also the possibility of links between periodontal

disease and systemic diseases has emerged. Another

look at treatment needs in the 21st Century would

be useful.

Actual market for periodontal

services

Fundamentally, need assessment focuses on which,

and how many, services should be utilized. In al-

most all circumstances, this will differ from the

services actually utilized. Even if methods to esti-

mate the need for periodontal services were very

precise, they would provide only part of the infor-

mation required to describe the economics of peri-

odontal services. To understand the actual market

for these services, the effective demand for the

services, as well as the availability of human and

nonhuman resources, need to be considered. These

226

supply and demand factors play an important role

in translating unmet need into effective demand.

An understanding of the economic and social con-

ditions of the population, reluctance to seek pro-

fessional dental care, and the role that price plays

in determining care received may help explain the

differences between services needed and services

actually provided.

Demand for care

In the United States, professionally trained dentists

provide most periodontal services through private

markets shaped by supply and demand (19, 22, 43).

Public funding for periodontal services is meager.

This makes an assessment of the demand for peri-

odontal dental services very important for under-

standing the actual delivery of care.

In assessing demand, the consumer is the primary

source that drives the use of dental services. The de-

mand for dental care reects the amount of care de-

sired by patients at alternative prices. The demand

for dental services is signicantly responsive to

changes in dental fees the higher the fees, the

lower the demand. Other factors that inuence the

level of demand include income, family size, popula-

tion size, education levels, prepayment coverage,

health history, ethnicity and age.

Most factors that positively inuence demand for

dental care have been expanding. The United

States economy has grown robustly for most of

the past two decades, resulting in an increase in

discretionary income among Americans (17, 20).

People are becoming more knowledgeable about

dental health and what is required to maintain it.

As the population has become more afuent and

educated, the value placed on oral health has in-

creased. In addition, the desire for esthetic den-

tistry has grown and will probably continue to do

so. All of these factors have enhanced the demand

for dental services, in general, and periodontal ser-

vices, in particular.

Trends in utilization and expenditures

Estimates of the number of periodontal services pro-

vided were developed from the data collected by the

1990 and 1999 ADA Survey of Dental Services

Rendered (14, 15). These surveys collected dental

procedure data on the most frequent procedures

performed from a representative sample of dentists.

When compared to the full range of codes found in

a national dental claims database, the codes used in

The economics of periodontal diseases

Table 4. Periodontal procedures as a percentage of all procedures, 1990 and 1999

1990 1999

Periodontal 27,284,300 28,490,800

All 1,070,763,200 1,159,835,500

Source: 1990 survey of dental services rendered, 1999 survey of dental services rendered (14, 15).

the surveys accounted for over 98% of all periodontal

procedures.

Dentists in private practice performed a total of

28.5 million periodontal procedures in 1999, which

was higher than the 27.3 million procedures per-

formed in 1990. See table4. Periodontal procedures

accounted for 2.7% of all procedures completed by

dentists in the earlier year but were reduced slightly,

to 2.5% of all procedures, in 1999.

Table5 shows per patient annual estimates of peri-

odontal services for 1999 by patient age. Periodontal

services in individuals younger than 25years old

were uncommon. Among those older than 25years,

utilization of these services increased markedly with

age, starting at 0.15 procedures per patient among

2534year olds and rising to a peak of 0.42 pro-

cedures per patient among 5564year olds. The

elderly received fewer periodontal service, at 0.27

procedures per patient. Two possible explanations

for the decrease in periodontal services among those

65years and older are: (i) loss of teeth and/or (ii) loss

of dental insurance.

When prophylaxes and oral hygiene instruction

were included, services per patient were much

larger, ranging from a low of 1.35 to a high of 1.99

procedures per patient. The age pattern was similar

to the previous age pattern, except among patients

Table 5. Periodontal services per patient for the year

1999

Age Periodontal Periodontal

Services and Preventive

25 0.01 1.47

25-34 0.15 1.35

35-44 0.19 1.49

45-54 0.31 1.68

55-64 0.42 1.99

65 0.27 1.57

Source: 1999 survey of dental services rendered (15).

227

younger than 25years old. This age group received a

commensurate amount of services, but the ad-

ditional services were primarily preventive pro-

cedures.

A useful measure of overall activity in the market

for periodontal services is the total (national) expen-

diture for those services. Annual estimates of total

dental expenditure are available through the Health

Care Financing Administrations (HCFA) Ofce of the

Actuary (26). However, these estimates cannot be

broken down by type of service. Estimates of expen-

ditures for periodontal services were developed by

applying the fees from the 1999 ADA Survey of Den-

tal Fees to the total number of procedures calculated

from the 1999 Survey of Dental Services Rendered.

Claims data were used to supplement and rene

these data sources.

The total expenditure on periodontal and preven-

tive procedures was $14.3 billion in 1999. See table

6. The majority of the expenditure on periodontal

and preventive procedures was spent on preventive

procedures; $9.8 billion out of $14.3 billion. Peri-

odontal services alone accounted for $4.4 billion in

expenditure.

Segmentation of the periodontal market

The periodontal market is segmented between the

two main providers of periodontal services, peri-

odontists and general practitioners. General prac-

Table 6. Expenditures on periodontal and preven-

tive procedures, 1999

Periodontal and Periodontal

Preventive

General Practitioners $11,886,127,391 $2,041,393,268

Periodontists $2,401,722,549 $2,321,396,502

Total $14,287,849,940 $4,362,789,770

Source: 1999 Survey of dental services rendered, 1999

survey of dental fees, electronic claims data (10, 15).

Brown et al.

titioners usually see patients with periodontal prob-

lems rst and then refer them, as necessary, to peri-

odontists. Each of these groups of dentists plays a

different role in managing periodontal disease which

is seen in the procedures they perform and the ex-

penditure they receive.

Procedures performed by periodontists

and general practitioners

In 1999, general practitioners performed 59.4% of the

estimated 28.5 million periodontal procedures; peri-

odontists performed 41.4% of the procedures. See

gure1. Other specialists, mainly oral and maxillo-

facial surgeons and pediatric dentists, performed the

remaining 0.8%.

The market share of these groups has remained

fairly constant. General practitioners increased their

share slightly during the 1990s, at the expense of

periodontists. In 1990, general practitioners carried

out 57.8% of periodontal procedures. By 1999, their

share had increased by 1.6% to 59.4%. The peri-

odontists share decreased from 41.4% to 39.7%. The

percent performed by other specialists stayed con-

stant over this time period.

When preventive procedures were included, the

percent carried out by general practitioners in 1999

increased to 88.6%. See gure2. While this percen-

tage has stayed the same over the last 10 years, the

percentage of periodontal and preventive pro-

cedures carried out by periodontists has dropped

from 5.3% to 4.8%. This difference has transferred to

other specialists, whose share increased from 6.1%

to 6.6%.

The most common periodontal procedures car-

ried out by general practitioners and periodontists

were periodontal maintenance and scaling and root

planing. See Fig. 3 and 4. Periodontists completed

5.8 million periodontal maintenance procedures in

Fig. 1. Type of dentists conducting periodontal pro-

cedures, 1990 and 1999.

228

1990 and 7.5 million in 1999. For general prac-

titioners, the comparable numbers were 4.0 million

rising to 5.2 million. As for scaling and root plan-

ing, periodontists performed 3.2 million and gen-

eral practitioners, 11.0 million in 1990. In 1999,

periodontists performed 1.5 million and general

practitioners, 9.4 million. From 1990 to 1999, the

total number of periodontal maintenance pro-

cedures increased from 9.8 million to 12.7 million,

while scaling and root planing procedures de-

creased from 14.2 million to 10.9 million.

Among periodontists, the increase in periodontal

maintenance was related to a decrease in prophy-

laxes. In 1979, before the periodontal maintenance

code came into existence, periodontists completed

3.4 million prophylaxes. By 1990, after its introduc-

tion, the national estimate for prophylaxes in peri-

odontists ofces was 1.1 million. In 1999, it was

811,100. At the same time, general practitioners

steadily increased the number of prophylaxes while

also increasing their number of periodontal main-

tenance procedures. In 1979, general practitioners

ofces performed 111.7 million prophylaxes. This

increased to 177.4 million in 1990 and 190.2 million

in 1999.

Scaling and root planing, the other common peri-

odontal procedure, has declined since 1990. In 1999,

general practitioners performed 1.6 million fewer

procedures of this type. Among periodontists, the

number of scaling and root planings dropped by

53.1% from 3.2 million to 1.5 million.

While the two most common procedures per-

formed by periodontists and general practitioners

were the same, these two procedures accounted for

a different proportion of the periodontal case mix.

In 1990, periodontal maintenance and scaling and

root planing accounted for 94.9% of all periodontal

procedures carried out by general practitioners, but

only 79.6% for periodontists. The percentage

Fig. 2. Type of dentists conducting periodontal and pre-

ventive procedures, 1990 and 1999.

The economics of periodontal diseases

Fig. 3. Periodontal procedures conducted by general practitioners, 1990 and 1999.

Fig. 4. Periodontal procedures conducted by periodontists, 1990 and 1999.

dropped to 5.8% for general practitioners in 1999.

But between 1990 and 1995, a new periodontal code,

debridement (04355 CDT-2), came into existence.

Debridement was the third most common procedure

conducted by general practitioners. When included

with periodontal maintenance and scaling and root

planing, these three accounted for 95.3% of general

practitioners periodontal procedures. Periodontists

performed relatively few debridements. General

practitioners performed 1.6 million compared to the

79,500 conducted by periodontists. Periodontal

maintenance, and scaling and root planing ac-

counted for 79.7% of the periodontal procedures

conducted by periodontists in 1999. When debride-

ment was included, the three accounted for 80.4%,

(Table6).

The ADA Survey of Services Rendered included

over 95% of periodontal procedures, by volume, but

did not include all of the different procedures that

periodontists perform. A more complete picture of

the procedure distribution of periodontists is dis-

229

played in Table7. These data were collected by the

American Academy of Periodontology with the 2000

Practice Prole Survey (5). Clearly, the more com-

plex procedures, such as bone replacement graft

(D4263 and D4264), osseous surgery (D4240), and

soft tissue grafts (D4271 and D4273) were an im-

portant and growing portion of periodontists prac-

Fig. 5. Percent of procedures performed by periodontists.

Brown et al.

tice. They also carried out substantial amounts of

localized delivery of chemotherapeutic agents

(D4281) and intravenous sedation (D9241 and

D9242). Nevertheless, scaling and root planing,

periodontal maintenance, prophylaxes and oral hy-

Table 7. Number of procedures performed in a typical month

N Mean Median SD Min Max

Periodic Oral Eval (D0120) 602 45.7 30 36.0 1 99

Limited Oral Eval Problem Focused (D0140) 601 17.4 10 17.4 1 99

Comprehensive Oral Eval (D0150) 681 31.4 28 19.7 1 99

Detailed and Extensive Oral Eval (D0160) 194 18.3 10 21.8 1 99

Intraoral Radiographs Complete Series (D0210) 686 19.8 15 16.7 1 99

Vertical Bitewings 7 to 8 Films (D0277) 396 19.3 10 19.3 1 99

Bacteriologic Studies (D0415) 219 3.8 2 6.2 0 60

Adult Prophylaxis (D1110) 417 36.2 20 37.4 1 99

Tobacco Counseling (D1320) 252 15.1 10 17.6 1 99

Oral Hygiene Instruction (D1330) 581 56.7 50 35.0 1 99

Root Amputation (D3450) 577 3.0 2 5.2 1 75

Hemisection (D3920) 399 2.1 1 2.4 1 21

Gingivectomy or Gingivoplasty (D4210 & D4211) 486 4.0 2 5.0 1 40

Gingival Curettage, surgical, per quad (D4220) 163 11.8 5 20.1 1 99

Gingival Flap Procedure, Per Quad 353 10.3 5 15.0 1 99

Apically Positioned Flap (D4245) 311 14.1 6 18.2 1 99

Clinical Crown Lengthening (D4249) 695 9.7 8 9.5 1 99

Osseous Surgery, Per Quad (D4260) 715 27.1 20 20.8 1 99

Bone Replacement Graft (D4263 & D4264) 675 12.5 9 14.7 1 99

Guided Tissue Regeneration (D4266 & D4267 648 9.2 5 12.2 0 99

Pedicle Soft Tissue Graft Procedure (D4270) 379 4.1 2 7.3 1 99

Free Soft Tissue Graft Procedure (D4271) 606 7.9 5 9.9 1 99

Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft (D4273) 652 7.6 5 7.9 1 99

Distal or Proximal Wedge (D4274) 443 8.0 4 11.7 1 99

Periodontal Scaling and Root Planing, Per Quad (D4341) 706 40.3 30 28.7 1 99

Full Mouth Debridement (D4355) 278 8.6 4 15.9 1 99

Localized Delivery of Chemotherapeutic Agents (D4381) 507 10.5 5 16.7 1 99

Periodontal Maintenance Procedures (D4910) 693 76.7 99 30.4 1 99

Surgical Placement of Endosteal Implant Body (D6010) 528 9.2 5 11.4 1 99

Abutment Placement: Endosteal Implant (D6020) 322 7.4 4 9.3 1 60

Surgical Placement: Eposteal/Transosteal Implant (D6040 & D6050) 15 5.0 2 6.6 1 20

Implant Maintenance Procedures (D6080) 367 8.2 5 12.4 1 99

Repair Implant Supported Prosthesis (D6090) 82 1.6 1 1.3 1 6

Implant Removal (D6100) 121 1.4 1 1.0 1 6

Surgical Exposure for Orthodontic Reasons (D7280) 281 2.0 1 1.9 1 12

Surgical Exposure to Aid Eruption (D7281) 176 1.8 1 1.6 1 10

Transseptal Fiberotomy (D7291) 316 2.4 1 3.2 1 23

Removal of Exostosis Mandible or Maxilla (D7471) 284 2.9 2 3.5 1 20

Sinus Lift Procedures (D7950) 223 2.1 1 1.8 1 15

Ridge Augmentation (D7955) 448 3.3 2 6.1 1 99

Frenulectomy (D7960) 574 3.2 2 4.1 1 50

Intravenous Sedation/Analgesia (D9241 & D9242) 175 12.2 6 16.2 1 99

Therapeutic Drug Injection (D9610) 38 9.5 4 19.1 1 99

Application of Desensitizing Medicament/Resin (D9910; D9911) 414 10.9 5 20.6 1 99

Behavior Management (D9920) 48 3.7 2 5.2 1 50 '

Occlusal Guard (D9940) 439 5.9 3 7.0 1 50

Occlusal Adjustment Limited (D9951) 533 5.0 2 7.4 1 56

Occlusal Adjustment Complete (D9952) 261 10.9 5 20.6 1 99

Source: 2000 practice prole survey (5).

230

giene instruction remained the largest activities in

the periodontal ofce.

Periodontists performed 39.7% of all periodontal

procedures in 1999. They only carried out approxi-

mately 14% of the scaling and root planing, 27% of

The economics of periodontal diseases

gingival surgery and 59% of periodontal mainten-

ance. However, periodontists performed the over-

whelming majority of more complicated procedures,

such as soft tissue grafts, osseous grafts and osseous

surgery. See Fig. 5. According to data provided by the

American Academy of Periodontology, the data in

Fig. 5 may underestimate the proportion of osseous

and soft tissue grafts provided by periodontists.

Thus, general practitioners carry out a larger pro-

portion of the more common procedures while peri-

odontists carry out almost all of the osseous pro-

cedures.

Expenditures received by periodontists

and general practitioners

Total expenditure on periodontal and preventive

procedures in 1999 were $14.3 billion. Although gen-

eral practitioners performed 88.6% of periodontal

and preventive procedures, they received $11.9 bil-

lion, or 83.2%, of the expenditure. Periodontists re-

ceived $2.4 billion.

When preventive procedures are removed, the an-

nual expenditure for periodontal procedures is $4.4

billion. General practitioners performed 59.4% of all

periodontal procedures in 1999, but earned only $2.0

billion, or 46.8%, of the expenditure. Periodontists

earned $2.3 billion even though they completed

fewer procedures.

Periodontists earned a larger proportion of the na-

tional periodontal expenditure because of the type

of procedures they do. The nonsurgical procedures

of periodontal maintenance, scaling and root plan-

ing, and debridement accounted for 95.3% of the

periodontal procedures carried out by general prac-

titioners, but only 80.4% of the procedures carried

out by periodontists. These procedures have a much

lower average fee than the surgical procedures,

which accounted for 19.4% of the procedures carried

out by periodontists, but only 4.7% of the procedures

carried out by general practitioners.

Periodontists also have higher fees than general

practitioners (10). The average fee for a scaling and

root planing (04341 CDT-2) in 1999 was about 40%

higher for periodontists compared to general prac-

titioners. The fees for more complex procedures,

such as osseous surgery (04260 CDT-2), were over

50% higher for periodontists. Osseous surgery was

a common procedure for periodontists but not for

general practitioners. The higher fees among peri-

odontists probably reect the more complex cases

they treat compared to general practitioners, and

231

also the additional postgraduate training which they

had to undertake.

Periodontal workforce

While demand drives the market for periodontal ser-

vices, for completeness, one should factor in the

supply side of the equation. This requires an evalu-

ation of the adequacy of the number and types of

dental workforce personnel, as well as their pro-

ductivity and work patterns.

Number of periodontists

According to the ADAs Distribution of Dentists sur-

vey, there were 4238 periodontists in the U.S. in 1998

(9). This represents a 57% increase in the number of

periodontists since 1982 (6). In comparison, the over-

all number of private practice dentists grew by 30%

from1982 to1998. However, the growthinthe number

of periodontists seems to have slowed from 1993 to

1998 (8). Periodontists made up 2.3% of all private

practice dentists in 1982. This percentage grew to

2.8% in 1993 and remained at this level in 1998.

Incomes of periodontists

According to the ADAs Survey of Dental Practice, the

average net income for independent periodontists

was $138,575 in 1992 (7). This was 41.2% higher than

the average net income earned by dentists in general

practice during 1992. Five years later, the average net

income for periodontists had increased to $165,640,

or 24.1% higher than the average for a general prac-

titioner (11). When measured in constant dollars

(base 1998), the increase in real net income for

periodontists was one-third as large as the increase

for general practice dentists $7,215 vs. $21,478.

This may indicate that the supply of periodontists

relative to the demand for their services is greater

than it is for general practitioners.

Selected practice characteristics of

periodontists and general practitioners

The segmentation of the periodontal market be-

tween periodontists and general practice dentists

was described above. According to the Survey of

Dental Practice, in 1997 these two groups of dentists

were equally likely to be employed in solo practice

73.9% for periodontists and 72.6% for general prac-

Brown et al.

tice dentists (11). The percentage of females in prac-

tice was also comparable 7.2% for periodontists

and 8.0% for general practice dentists. Periodontists

were somewhat more likely than general practice

dentists to work part-time 18.3% vs. 15.7%. Peri-

odontists were more likely to employ a hygienist

85.8% vs. 71.2%. Average appointment length was

greater for periodontists 56.3min vs. 47.9min, and

periodontists reported a higher number of visits per

patient per year 5.8 vs. 3.4.

Among solo periodontists, the average number of

hours per week inthe ofce declinedfrom38.2 in1993

to 36.9 in 1998. Hours spent treating patients also de-

clined from 34.3 to 31.6. Average visits per week ex-

cluding hygienist appointments declined from48.2 to

45.2. However, the average appointment length in-

creased by almost three minutes, from 53.9min to

56.7min. Average number of weeks worked per year

held steady at 48, while there was an increase of ve

percentage points in those indicating part-time em-

ployment, from 12.4% in 1993 to 17.6% in 1998.

When assessing the adequacy of the periodontal

workforce, the segmentation of the market is import-

ant. Periodontists carry out the vast majority of the

more complicated procedures. General practitioners

perform most of the scaling and root planing and

other, less complex, procedures; however, peri-

odontists also perform a signicant proportion of

these services. Dental hygienists perform the huge

majority of preventive services. Depending on the

services being considered, the numbers of all three

types of providers are important for workforce evalu-

ation.

Currently, dentists nd they have a difculty lling

vacant positions for dental hygienists (11, 13). Thus,

rapid expansion of preventive services, without a

commensurate expansion of available dental hygien-

ists could be difcult. However, there is no indi-

cation that an expansion of preventive services

would occur without major new funding programs.

All periodontal services performed by general

practitioners represent less than ve percent of the

services carried out by general practitioners. General

practitioners have been increasing the percentage of

periodontal services in their practices slightly. With

over 100,000 general practitioners, the capacity to

further expand the more routine periodontal ser-

vices appears considerable.

Periodontists are critical to the provision of more

complicated therapy necessary for the management

of advanced cases of periodontal disease. General

practitioners would not be able to immediately ll a

void, if one should occur. However, there does seem

232

to be at least some capacity for these services to be

expanded. Almost 1 in 5 periodontists practice part-

time. If that percentage were to decline, capacity

would be increased.

Finally, the adequacy of the periodontal workforce

depends very much on the demand for those ser-

vices. The size of the periodontal market has been

constant since 1990. Need for periodontal treatment

is considerable, but all needed care may not be fully

realized. Utilization of periodontal procedures is in-

creasing at 0.5% annually, but this does not match

the rate of increase in the population and the num-

ber of periodontists (1.2%). With the current demand

conditions, there seems to be an adequate supply of

periodontists and of periodontal services.

A look at the future

After considering the U.S. as a case study of peri-

odontal services delivery, it is now time to take a

more global perspective. The prospects for peri-

odontal health, as well as the volume of and expen-

ditures for periodontal services, are far from certain.

When it comes to the future, everyones crystal ball

is cloudy.

This is especially true for the demand for dental

care, because future demand will depend on the

growth of the economies in various countries, socio-

economic shifts in the population, changes in thera-

peutic and preventive interventions, and the impact

of changing oral disease rates as well as the structure

of nancing arrangements. In those countries with

growing economies, the percentage of the popula-

tion that utilize periodontal services is likely to in-

crease with increasing afuence. Increasingly, edu-

cated populaces are likely to provide a stimulus to

dental demand in many countries. If major new

funding programs become available in some coun-

tries, or if major new treatment opportunities

emerge, per capita utilization may increase even

more.

There is consensus that the worlds population will

continue to grow. In the United States, the popula-

tion will also age and become more diverse. To a cer-

tain extent this is also true for the rest of the indus-

trialized world. Population growth in the nonindus-

trialized world is projected to increase even more

rapidly in the future than it has in the past. This will

result in an increase in the percentage of the worlds

population living in those regions of the world that

are not currently considered afuent. In those coun-

The economics of periodontal diseases

tries the age distribution is likely to become even

younger. Not only total population, but also the age

and socioeconomic distribution of the worlds popu-

lation, will be important for future demand for peri-

odontal services.

The future prevalence and extent of periodontal

disease is also uncertain. In the United States and

other afuent countries, both may be trending

downward. This could decrease future need for com-

plicated periodontal therapy in those countries. Fu-

ture prevalence and severity in the rest of the world

is unknown. For worldwide reduction of periodontal

disease, much depends on health education, pro-

motion and prevention.

Scientic advances could provide entirely new

treatment options. Technical and scientic advances

will occur but their timing and effect on demand are

unpredictable. Documentation of causal links be-

tween oral disease and some systemic diseases are

less certain and their impact on demand is more

problematic. Nevertheless, if it is shown that appro-

priate periodontal disease management can alter the

courses of some systemic diseases for the better, the

impact on the delivery of periodontal services could

be huge.

Periodontal delivery systems will probably not all

evolve in the same manner. The American economic

model for periodontal services and delivery is a good

model. It has largely been successful at meeting the

needs and desires of the U.S. population. It is a hi-

tech, private market model. These features are con-

sistent with the cultural preferences of the American

citizenry. Despite the large amount of tertiary peri-

odontal care that the U.S. provides, the nation has not

neglected prevention. The U.S. is one of the more

periodontally healthy countries. More work needs to

be conducted to bring this high quality care delivered

by extremely well-trained health professionals to

those inthe Americansociety that currently donot ac-

cess dental care to the same extent as the majority of

the population. This is an achievable goal but it re-

quires commitment and political will on the part of all

segments of the U.S. population.

While successful, the American model is not the

only model, even for afuent countries. There will

be commonalities in the features of a periodontal

services delivery system in industrialized countries,

but cultural and other diversity will ensure that sev-

eral models evolve in parallel. It is reasonable to ex-

pect that division of labor will become more pro-

nounced as the world economy expands and the

science-base advances. Afuent countries have the

economic resources to support more specialization,

233

and periodontology has been accorded some degree

of recognition as a specialty in several countries.

However, some countries may opt for less tertiary

treatment than the U.S. provides. This implies less

need for advanced periodontal training and prob-

ably less segmentation of the market between gener-

alists and specialists. Financing arrangements also

vary, ranging from signicant state supported n-

ancing to predominantly private prepayment to very

little third party nancing.

The nonindustrialized countries will necessarily

follow a different model until they generate the

economic strength to enable more resources to be

devoted to dentistry, in general, and periodontal

care, in particular. Much of the periodontal care

available in these countries will continue to be pro-

vided by nonprofessionally trained individuals. Un-

fortunately, extractions, and outright neglect, will

continue to play a central role in the short-run. How-

ever, prevention has a huge potential to not only im-

prove health, but to do so in a cost-effective manner

(17, 20). One can hope that prevention will become

a central strategy for the control of periodontal dis-

eases around the world. This will not be easy. Cur-

rently, there is not a preventive intervention for peri-

odontal diseases with the potency that uoride has

for caries. However science is progressing rapidly.

Powerful new preventive, diagnostic, and treatment

options are on the way, and the world can look for-

ward to improved periodontal health in the future

(12).

References

1. Albandar JM. Periodontal diseases in North America. Peri-

odontol 2000 2002: 3169.

2. Albandar JM. Global risk factors and risk indicators for

periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 2002: 177206.

3. Albandar JM, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Destructive peri-

odontal disease in adults 30 years of age and older in the

United States, 19881994. J Periodontol 1999: 70: 1329.

4. Albandar JM, Kingman A. Gingival recession, gingival

bleeding, and dental calculus in adults 30 years of age and

older in the United States, 19881994. J Periodontol 1999:

70: 3043.

5. American Academy of Periodontology. 2000 Practice Pro-

le Survey: Characteristics and Trends in Private Peri-

odontal Practice. Chicago: American Academy of Period-

ontology, 2001.

6. American Dental Association. 1982 Distribution of dentists

in the United States by region and state. Chicago: American

Dental Association, 1983.

7. American Dental Association. Specialists in private prac-

tice. In: 1993 Survey of Dental Practice. Chicago: American

Dental Association, 1993.

8. American Dental Association. 1993 Distribution of dentists

Brown et al.

in the United States by region and state. Chicago: American

Dental Association, 1994.

9. American Dental Association. 1998 Distribution of dentists

in the United States by region and state. Chicago: American

Dental Association, 1999.

10. American Dental Association. 1999 Survey of Dental Fees.

Chicago: American Dental Association, 2000.

11. American Dental Association. 1998 Survey of Dental Prac-

tice. Chicago: American Dental Association, 2000.

12. American Dental Association. Future of dentistry. Chicago:

American Dental Association, Health Policy Resources

Center, 2001.

13. American Dental Association and International Com-

munications Research. 1999 Workforce Needs Assessment

Survey. Total U.S. Results. In: Dental health policy analysis

series. Chicago: American Dental Association, 2000.

14. American Dental Association. 1990 Survey of dental ser-

vices rendered. Chicago: American Dental Association, Sur-

vey Center, 1994.

15. American Dental Association. 1999 Survey of dental ser-

vices rendered. Chicago: American Dental Association, Sur-

vey Center, 2001.

16. Arbes SJ Jr, Slade GD, Beck JD. Association between extent

of periodontal attachment loss and self-reported history

of heart attack: an analysis of NHANES III data. J Dent Res

1999: 78: 17771782.

17. Beazoglou T, Brown LJ, Hefey D. Dental care utilization

over time. Soc Sci Med 1993: 37: 14611472.

18. Beck JD, Garcia RA, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher SN.

Periodontal disease and cardiovacular disease. J Peri-

odontol 1996: 67: 11231137.

19. Brown LJ. Contrasting the economic outlook for dentistry

and medicine. J Med Pract Manage 1989: 5: 817.

20. Brown LJ, Beazoglou T, Hefey D. Estimated savings in

U.S. dental expenditures, 197989. Public Health Rep 1994:

109: 195203.

21. Brown LJ, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Periodontal status in

the United States, 19881991: prevalence, extent, and

demographic variation. J Dent Res 1996: 75: 672683.

22. Brown LJ, Lazar V. The economic state of dentistry.

Demand-side trends. J Am Dent Assoc 1998: 129: 1685

1691.

23. Dasanayake A. Poor periodontal health of the pregnant

woman is a risk factor for low birth weight. Ann Peri-

odontol 1998: 3: 206212.

24. Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes

mellitus: a two-way relationship. Ann Periodontol 1998: 3:

5161.

25. Grossi SG, Skrepinski FB, De Caro T, Robertson DC, Ho

AW, Dunford RG, Genco RJ. Treatment of periodontal dis-

ease in diabetics reduces glycosolated hemoglobin. J Peri-

odontol 1997: 67: 713719.

26. Health Care Financing Administration and Ofce of the

Acutary. 1996 National Health Expenditures (NHE). 1996.

27. Jeffcoat MK et al. Periodontal infection and pre-term birth.

J Am Med Assoc 2001: 132: 875880.

28. Kornman KS, Grave A, Wang HY, di Giovire FS, Newman

MG, Pirk FW, Wilson TG Jr, Higginbottom FL, Duff GW.

234

The interleuken-1 genotype as a severity factor in adult

periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 1997: 24: 7277.

29. Le HA. The Gingival Index, the Plaque Index and the Re-

tention Index systems. J Periodontol 1967: 38 (Suppl.): 6.

30. Le HA. The natural history of periodontal disease in man:

the rate of periodontal destruction before 40 years of age.

J Periodontol 1978: 49: 607620.

31. Le HA, nerud , Boysen H, Smith M. The natural history

of periodontal disease in man: tooth mortality rates before

40 years of age. J Periodontal Res 1978: 13: 563572.

32. Miller AJ, Brunelle JA, Carlos JP, Brown LJ, Le HA. Oral

health United States adults. Community Dent Health

1988: 5: 6971.

33. Mitchell-Lewis D, Engebretson SP, Chen J, Lamster IB, Pa-

papanou PN. Periodontal infections and pre-term labor:

early ndings from a cohort of young minority women in

New York. Eur J Oral Sci 2001: 109: 3439.

34. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and health stat-

istics: plan and operation of the health and nutrition ex-

amination survey, United States 197173. Hyattsville, MD:

National Center for Health Statistics, 1977.

35. Neely AL, Holford TR, Loe H, Anerud A, Boysen H. The

natural history of periodontal disease in man. Risk factors

for progression of attachment loss in individuals receiving

no oral health care. J Periodontol 2001: 72: 10061015.

36. Offenbacher SN, Katz V, Fertik G, Collins J, Boyd D, Mayno

E, McKaig R, Beck J. Periodontal disease as a possible risk

factor for pre-term low birthweight. Periodontol 1996: 67:

11031113.

37. Oliver RC, Brown LJ. Changing patterns of periodontal dis-

ease: a decline in treatment needs. J Dent Res 1988: 67:

355.

38. Oliver RC, Brown LJ, Loe H. An estimate of periodontal

treatment needs in the U.S. based on epidemiologic data.

J Periodontol 1989: 60: 371380.

39. Oliver RC, Brown LJ, Le HA. Periodontal treatment needs.

Periodontol 2000 1993: 2: 150160.

40. Russell AL. A system of classication and scoring for

prevalence surveys of periodontal disease. J Dent Res 1956:

35: 350359.

41. Scannapieco FA. The role of oral bacteria in respiratory

infection. J Periodontol 1996: 70: 793802.

42. Taylor GW et al. Severe periodontitis and risk for poor gly-

cemic control in patients with non-insulin dependent dia-

betes mellitus. J Periodontol 1996: 67: 10851093.

43. Tuominen R. Health Economics in Dentistry. Malibu, CA:

MedEd, 1994.

44. US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral

health of United States adults: the national survey of oral

health in U.S. employed adults and seniors, 19851986.

NIH Publication No. 872868. Bethesda, Maryland: Na-

tional Institute of Dental Research. 1987.

45. US Department of Health and Human Services and. Na-

tional Center for Health Statistics. Third national health

and nutrition examination survey, 19881994, NHANES III

Examination Data File (CD-ROM). Public use data le

documentation number, 76200. US Department of Health

and Human Services: 1996.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Respiratory System Notes - KEYDocument3 pagesRespiratory System Notes - KEYjoy100% (1)

- Amyotrophic Lateral SclerosisDocument70 pagesAmyotrophic Lateral SclerosisLorenz Hernandez100% (1)

- Physician Assistant Certification and Recertification Exam Review - PANRE - PANCEDocument14 pagesPhysician Assistant Certification and Recertification Exam Review - PANRE - PANCEThe Physician Assistant Life100% (3)

- A Mental Healthcare Model For Mass Trauma Survivors - M. Basoglu, Et. Al., (Cambridge, 2011) WW PDFDocument296 pagesA Mental Healthcare Model For Mass Trauma Survivors - M. Basoglu, Et. Al., (Cambridge, 2011) WW PDFraulPas encore d'évaluation

- Portfolio Template for Diploma in Occupational MedicineDocument11 pagesPortfolio Template for Diploma in Occupational MedicineChengyuan ZhangPas encore d'évaluation

- Per I Tons IllerDocument25 pagesPer I Tons IllerkochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Cytokine Gene Polymorphism and Immunoregulation in Periodontal DiseaseDocument25 pagesCytokine Gene Polymorphism and Immunoregulation in Periodontal DiseasekochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 3mespe Cements v5Document12 pages3mespe Cements v5kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijp 18 5 Mack 9Document6 pagesIjp 18 5 Mack 9kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 14Document13 pages14kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Antigen-Presentation and The Role of Dendritic Cells in PeriodontitisDocument23 pagesAntigen-Presentation and The Role of Dendritic Cells in PeriodontitiskochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 15Document9 pages15kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijp 18 5 Grandini 7Document6 pagesIjp 18 5 Grandini 7kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 11Document16 pages11kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijp 18 5 Editorial 1Document3 pagesIjp 18 5 Editorial 1kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijp 18 5 Hassel 11Document5 pagesIjp 18 5 Hassel 11kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Peri-Implant Bone Loss As A Function of Tooth-Implant DistanceDocument7 pagesPeri-Implant Bone Loss As A Function of Tooth-Implant DistancekochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijp 18 5 Coward 8Document9 pagesIjp 18 5 Coward 8kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijp 18 5 Elmowafy 13Document2 pagesIjp 18 5 Elmowafy 13kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Original Water Content in Acrylic Resin On Processing ShrinkageDocument2 pagesEffect of Original Water Content in Acrylic Resin On Processing ShrinkagekochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 6Document15 pages6kochikaghochi100% (1)

- Ijp 18 5 Botelho 2Document6 pagesIjp 18 5 Botelho 2kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 10Document10 pages10kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Use of Oral Implants in Compromised Patients: Daniel Van SteenbergheDocument3 pagesThe Use of Oral Implants in Compromised Patients: Daniel Van SteenberghekochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 9Document14 pages9kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 8Document15 pages8kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnosis of Periodontal Manifestations of Systemic DiseasesDocument13 pagesDiagnosis of Periodontal Manifestations of Systemic DiseaseskochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 3Document10 pages3kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 7Document8 pages7kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 5Document13 pages5kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 4Document18 pages4kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- Preoperative Radiologic Planning of Implant Surgery in Compromised PatientsDocument14 pagesPreoperative Radiologic Planning of Implant Surgery in Compromised PatientskochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 12Document13 pages12kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 14Document10 pages14kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- 11Document39 pages11kochikaghochiPas encore d'évaluation

- AcidifiersDocument17 pagesAcidifiersKarim Khalil100% (3)

- Joint InfectionsDocument10 pagesJoint InfectionsJPPas encore d'évaluation

- Hybrid Hyrax Distalizer JO PDFDocument7 pagesHybrid Hyrax Distalizer JO PDFCaTy ZamPas encore d'évaluation

- FEVER Approach (Paeds)Document3 pagesFEVER Approach (Paeds)NorFarah Fatin AnuarPas encore d'évaluation

- A Review On Acacia Arabica - An Indian Medicinal Plant: IJPSR (2012), Vol. 3, Issue 07 (Review Article)Document11 pagesA Review On Acacia Arabica - An Indian Medicinal Plant: IJPSR (2012), Vol. 3, Issue 07 (Review Article)amit chavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Europe PMC study finds computerized ADHD test improves diagnostic accuracyDocument22 pagesEurope PMC study finds computerized ADHD test improves diagnostic accuracyBudi RahardjoPas encore d'évaluation

- Don't Steal My Mind!: Extractive Introjection in Supervision and TreatmentDocument2 pagesDon't Steal My Mind!: Extractive Introjection in Supervision and TreatmentMatthiasBeierPas encore d'évaluation

- Daftar Obat Slow Moving Dan Ed Rawat Inap Maret 2021Document8 pagesDaftar Obat Slow Moving Dan Ed Rawat Inap Maret 2021Vima LadipaPas encore d'évaluation

- This Just In!: Queen Pin Carla!Document10 pagesThis Just In!: Queen Pin Carla!BS Central, Inc. "The Buzz"Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anvisa National Health Surveillance AgencyDocument52 pagesAnvisa National Health Surveillance AgencyVimarsha HSPas encore d'évaluation

- Navidas-Case StudyDocument5 pagesNavidas-Case StudyFran LanPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Manufacturing Units With Valid Ayush 64 Technology Transfer Agreement As On 15.06.2021Document5 pagesList of Manufacturing Units With Valid Ayush 64 Technology Transfer Agreement As On 15.06.2021Sunira EnterprisesPas encore d'évaluation

- Medicine in Situ Panchen TraditionDocument28 pagesMedicine in Situ Panchen TraditionJigdrel77Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kerala PDocument106 pagesKerala PJeshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Class 11 English Snapshots Chapter 7Document2 pagesClass 11 English Snapshots Chapter 7Alpha StarPas encore d'évaluation

- CCMP 2020 Batch Cardiovascular MCQsDocument2 pagesCCMP 2020 Batch Cardiovascular MCQsharshad patelPas encore d'évaluation

- Click Here Click Here To View Optimized Website For Mobile DevicesDocument4 pagesClick Here Click Here To View Optimized Website For Mobile DevicesFirman SalamPas encore d'évaluation

- Minor Surgical Procedures in Maxillofacial SurgeryDocument65 pagesMinor Surgical Procedures in Maxillofacial SurgerydrzibranPas encore d'évaluation

- Physiotherapy in LeprosyDocument4 pagesPhysiotherapy in LeprosymichaelsophianPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Avoid Medication ErrorsDocument2 pagesHow To Avoid Medication ErrorsLorenn AdarnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Akupuntur 7Document9 pagesAkupuntur 7Ratrika SariPas encore d'évaluation

- Jeff Hooper ThesisDocument445 pagesJeff Hooper ThesisRan CarilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Pacemaker - Mayo ClinicDocument15 pagesPacemaker - Mayo ClinicShehab AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

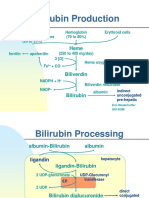

- Bilirubin Production: Hemoglobin (70 To 80%) Erythroid Cells Heme Proteins Myoglobin, Cytochromes (20 To 25%)Document5 pagesBilirubin Production: Hemoglobin (70 To 80%) Erythroid Cells Heme Proteins Myoglobin, Cytochromes (20 To 25%)Daffa Samudera Nakz DoeratipPas encore d'évaluation

- Inserto CHOL - LIQ SPINREACTDocument2 pagesInserto CHOL - LIQ SPINREACTIng BiomédicoPas encore d'évaluation