Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

2011 Poverty Food Insecurity Williams

Transféré par

wahyupujilestari0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

16 vues9 pagesabout poverty food insecurity

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentabout poverty food insecurity

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

16 vues9 pages2011 Poverty Food Insecurity Williams

Transféré par

wahyupujilestariabout poverty food insecurity

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 9

NEW RESEARCH

Poverty, Food Insecurity, and the Behavior

for Childhood Internalizing

and Externalizing Disorders

Natalie Slopen, M.A., Garrett Fitzmaurice, Sc.D., David R. Williams, M.P.H., Ph.D.,

Stephen E. Gilman, Sc.D.

Objective: This study investigated the associations of poverty and food insecurity over a

2-year period with internalizing and externalizing problems in a large, community-based

sample. Method: A total of 2,810 children were interviewed between ages 4 and 14 years at

baseline, and between ages 5 and 16 years at follow-up. Primary caregivers reported on

household income, food insecurity, and were administered the Child Behavior Checklist, from

which we derived indicators of clinically signicant internalizing and externalizing problems.

Prevalence ratios for the associations of poverty and food insecurity with behavior problems

were estimated. Results: At baseline, internalizing and externalizing problems were signif-

icantly more prevalent among children who lived in poor households than in nonpoor

households, and among children who lived in food insecure households than in food-secure

households. In adjusted analyses, children from homes that were persistently food insecure

were 1.47 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.94) times more likely to have internalizing problems and 2.01

(95% CI 1.21 to 3.35) times more likely to have externalizing problems compared with

children from households that were never food insecure. Children from homes that moved

from food secure to insecure were 1.78 (95% CI 1.07 to 2.94) times more likely to have

externalizing problems at follow-up. Conclusions: Persistent food insecurity is associated

with internalizing and externalizing problems, even after adjusting for sustained poverty and

other potential confounders. These results implicate food insecurity as a novel risk factor for

child mental well-being; if causal, this represents an important factor in the etiology of child

psychopathology, and potentially a new avenue for prevention. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc.

Psychiatry, 2010;49(5):444452. Key Words: Food insecurity, Poverty, Internalizing prob-

lems, Externalizing problems, Prospective.

P

overty and food insecurity have adverse

impacts on the course of child develop-

ment, in part by raising the risk for care-

giver depression

1-3

and for chronic iron de-

ciency and vitamin deciencies.

4,5

According to

the U.S. Census, 37.3 million persons in the

United States (12.5%) were poor in 2007, as

specied by the U.S. federal poverty guidelines,

which take into account total household income

and number of people residing in the household;

for a family of four, this equates to an income

below $21,203.

6

During this time, approximately

18.0% of children were poor, with black (or

African American) and Hispanic children dispro-

portionately affected. Food insecurity, dened as

limited or uncertain availability of food because

of inadequate resources, is one of many difcul-

ties associated with poverty.

7

In a 2007 report, the

U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated that

11% of U.S. households experienced food insecu-

rity in 2005. Food insecurity was almost twice as

common for households with children relative to

households without children (15.6% vs. 8.5%),

and 30% of single female-households were food

insecure.

7

Like poverty, risk of food insecurity is

also patterned by race/ethnicity. In the U.S.,

there is overlap in the populations of individuals

meeting the denitions of poverty and food in-

security; yet, individuals with food insecurity are

This article is discussed in an editorial by Dr. Tamara Dubowitz on

page 437.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 444 www.jaacap.org

not always poor, and poor individuals are not

always food insecure.

7

For children, experiences

of household poverty and/or food insecurity

may have an impact on numerous domains of

life, including family processes and parental

well-being, cognitive and academic performance,

and general health outcomes; each of these fac-

tors may affect internalizing or externalizing

problems.

8,9

There is limited prospective research that has

considered the relationship among poverty, food

insecurity, and childrens mental health. Prospec-

tive study designs enable a rigorous test of the

effect of these determinants on child mental

health, and are most informative for examining

causal inference; this is of substantial importance

for researchers and clinicians who are interested

in identifying optimal points for intervention.

Several prospective studies on the relationship

between poverty and child psychopathology

suggest that chronic poverty is associated with

an elevated risk of psychopathology.

10-13

For

example, Bor et al.

10

found that chronic low

family income (near or below the poverty line in

Australia) was associated with an increased risk

of internalizing, externalizing, and social, atten-

tional, and thought problems at age 5 years.

10

Costello et al

11

found that an income supplemen-

tation that moved families out of poverty was

associated with a reduction in oppositional de-

ant disorder and conduct disorder symptoms.

After the income supplementation, the level of

behavioral symptoms for children who were

poor at baseline but no longer poor at follow-up

fell to those of children who were never poor,

whereas the level of symptoms among persis-

tently poor children remained elevated in com-

parison to the never-poor children.

We are not aware of any prospective research

on poverty and child mental health that has

addressed the issue of food insecurity; however,

cross-sectional studies suggest an independent

link between food insecurity and higher levels of

child behavioral/emotional problems.

2,14-19

For

example, Whitaker et al.

2

analyzed data from the

Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study and

found a positive gradient in the prevalence of

child behavior problems with increasing levels of

food insecurity among children at age 3 years

(i.e., 22.7% for those who were fully food inse-

cure, 31.1% for marginally food insecure, and

36.7% for food insecure). Alaimo et al.

14

analyzed

nationally representative adolescent data and

found that food-insufcient adolescents were ap-

proximately four times more likely to meet diag-

nostic criteria for dysthymia and ve times more

likely to have made a suicide attempt; in contrast,

low family income (i.e., 130% of the poverty

line) did not predict these outcomes. We were

able to locate only one study that used a prospec-

tive design to examine the impact of food inse-

curity on child development,

20

although this

study focused on social skills rather than inter-

nalizing and externalizing symptoms. Although

prospective research on food insecurity and child

mental health is lacking, there has been some

work in this area with adults. In a prospective

study over 3 years, Hein et al

1

found that onset

of food insufciency status was positively asso-

ciated with onset of maternal major depression

status while adjusting for many sociodemo-

graphic characteristics, including income. The

Project on Human Development in Chicago

Neighborhoods (PHDCN) provides an opportu-

nity to investigate the role of poverty and food

insecurity on risk for childhood psychopathol-

ogy. The present study used data over a 2 year

period to examine the impact of trajectories of

household poverty and food insecurity on

change in child outcomes. We hypothesized that

(a) persistent poverty and movement into pov-

erty status are positively associated with inter-

nalizing and externalizing problems, and (b) per-

sistent food insecurity and movement into food

insecure status are positively associated with

internalizing and externalizing problems.

METHOD

Sample

The PHDCN includes a prospective study of children

and their families from 80 distinct neighborhoods over

an 8-year period (19952002). A three-stage sampling

design was used to enroll children and their primary

caregivers into the study: rst, 80 neighborhood clus-

ters from all neighborhoods in Chicago were selected

based on a stratied probability sample of neighbor-

hood clusters heterogeneous on race, ethnicity, and

income; second, block groups within each neighbor-

hood cluster were selected; and third, households with

children 6 months post partum, aged 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and

18 living in the selected block groups, were enrolled in

the study.

21

The participation rate at the time of

recruitment was 75%. The current study uses data

from children aged 4 through 14 years collected be-

tween 1997 and 2001; children and primary caregivers

were interviewed twice, with an average period of 24

months between interviews.

POVERTY, FOOD INSECURITY, AND BEHAVIOR

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 445 www.jaacap.org

Internalizing and Externalizing Problems

Internalizing and externalizing problems were measured

using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for children 4

through 18 years of age.

22

This measure was adminis-

tered to the primary caregiver at baseline and follow-up.

The CBCL contains questions pertaining to the childs

emotions and behavior in the past 6 months. The care-

giver was asked to identify whether each statement has

been very true, somewhat true, or not true. The

internalizing subscale provides a rating for the extent to

which the child has exhibited symptoms of anxiety,

depression, or withdrawal. The externalizing subscale

provides a rating of the extent to which the child has

exhibited symptoms of aggression, hyperactivity, or non-

compliance. Both scales have satisfactory validity and

internal consistency.

22

We dened problem levels of

internalizing and externalizing as scores at or above the

90

th

percentile (T-score 64, based on published norms).

High scores on the CBCL 1991/4-18 correspond closely

to clinical diagnostic outcomes (i.e., anxiety, mood, dis-

ruptive behavior, and conduct disorders)

23,24

dened by

the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disor-

der(DSM) III-R

25

Poverty Status

Family poverty was dened according to the U.S.

federal poverty threshold, which was originally de-

signed to identify individuals and families with insuf-

cient income to meet basic needs. The federal poverty

threshold takes into account total household income

and number of persons living in the household. We

created a measure of income to needs for this study

by calculating a ratio of household income over the

federal poverty threshold; an income-to-needs ratio of

less than 1 indicates that a family is below the poverty

line. The federal poverty threshold has particular sa-

lience for the current study, given that government

benets such as welfare are linked to it. We dened

family poverty over the course of the study based on

poverty status at both time points (persistently poor,

previously poor, newly poor, and never poor).

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity refers to limited or uncertain access

to nutritionally adequate and safe foods due to lack of

resources (p. 278).

26

The current gold-standard mea-

sure of food insecurity is the 18-item U.S. Food Secu-

rity Scale, which includes eight child-referenced items

that make up the Childrens Food Security Scale.

7

Unfortunately, the PHDCN did not include a validated

measure of food insecurity; only a single item was

included, which may only partially capture the con-

struct of interest. In this study, the primary caregiver

provided information about household food insecurity

status at baseline and follow-up in response to a single

question, which referred to the past 6 months: Has

there been a time when there was not enough money

at home to buy food? (yes/no). This variable was

strongly correlated with caregiver report of having to

cut his/her meal size one or more times in the past 6

months (correlation 0.65, p .0001), which provides

some assurance that our item reect the construct of

interest. These two items were the only interview

questions that measured access to food. We created a

four-category variable to reect trajectory of food

insecurity over time (persistently food insecure, previ-

ously food-insure, newly food insecure, never food

insecure).

Demographic Characteristics

We included several child and primary caregiver co-

variates in the analyses. Child covariates included age

at interview, gender, and race/ethnicity (black, white,

Hispanic, and other). Household characteristics in-

cluded the number of people residing in the house-

hold, and caregiver cohabitation status over time

(never partnered/married; newly partnered/married;

previously partnered/married; always partnered/

married). Primary caregiver covariates included age at

baseline and follow-up, education at baseline (high

school degree vs. less than high school), major depres-

sion at baseline (based on an adapted version of the

Composite International Diagnostic Interview short

form for DSM-IV

27

), and alcohol problems at baseline

(dened as a scoring 3 on the Short Michigan Alco-

hol Screening Test

28

).

Statistical Analyses

Regression analyses were used to relate internalizing

and externalizing problems to patterns of poverty and

food insecurity. Our rst set of models examined

baseline associations among poverty, food insecurity,

and problem status while adjusting for sociodemo-

graphic characteristics of the child (age, gender, and

race/ethnicity), household (cohabitation status, num-

ber of persons in the household), and caregiver (age,

depression, education, and alcohol problem). Our sec-

ond set of models examined the effect of poverty and

food insecurity trajectories on internalizing and exter-

nalizing problems at follow-up, controlling for base-

line problem status, and child, household and care-

giver covariates. The prospective models for

internalizing and externalizing problems followed the

same model-building strategy: the rst two models

estimated the separate effects of poverty and food

insecurity, and the third model included poverty and

food insecurity simultaneously. All analyses were

based on Poisson regression models, which yield prev-

alence ratios for the relation between the risk factors of

interest and child internalizing and externalizing prob-

lems.

29-31

Generalized estimating equations were used

to obtain variance estimates that account for the nested

structured of the data.

SLOPEN et al.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 446 www.jaacap.org

Across the variables in our analysis, the percentage

of participants with missing data ranged from 0% to

27%; more than half of our sample had at least one

missing value, and the overall participation rate at

wave 3 was 79.5%. Multiple imputation of missing

data was performed using IVEware,

32

retaining all

respondents who were enrolled in age cohorts 3, 6, and

9 at wave 1 (N 2,810). This strategy best preserved

the original sample characteristics and reduced bias

that could result from attrition. PROC MIANALYZE in

SAS v.9.1 was used to combine the results from the 10

imputed datasets for all analyses.

RESULTS

The mean age of the child participants was 8.2

years at baseline, and 10.7 years at follow-up

(Table 1). Female participants comprised slightly

more than half of the sample (50.5%). Approxi-

mately 32% of the sample was non-Hispanic

black, 14% was non-Hispanic white, 42% was

Hispanic, and 12% was coded as other race.

The mean age of the primary caregivers in the

sample was 35.6 years at baseline and 38.1 years

at follow-up. The prevalence of poverty and food

insecurity declined between baseline and follow-

up: at baseline, 40% of families in the study were

below the poverty line, and 23% of families were

food insecure; at follow-up, the prevalences fell

to 30% and 18%, respectively. Although poverty

and food insecurity have some degree of overlap,

these constructs are not entirely overlapping: at

baseline, 52% of the sample was neither food

insecure or poor, whereas 15% of our sample was

both food insecure and poor; 8% was food inse-

cure but not poor, whereas 25% was poor but not

food insecure.

The prevalence of internalizing and externaliz-

ing problems was stable across waves, with ap-

proximately 18% of children categorized as having

internalizing problems, and 7% of children catego-

rized as having externalizing problems at both time

points. There was a relatively high degree of co-

morbidity between internalizing and externalizing

problems: at baseline, 27% of children with inter-

nalizing problems also met criteria for externalizing

problems; at follow-up, 25% of children with inter-

TABLE 1 Characteristics of Study Participants (N 2,810)

Characteristic

Baseline Follow-up

N % Mean (SE) N % Mean (SE)

Below poverty line 1,135 40.38 856 30.48

Food insecure 643 22.90 516 18.36

Total household income ($ US) 2,810 31,1163 (481.11) 2810 37,669 (1101.54)

Child characteristics

Internalizing problems 508 18.07 482 17.16

Externalizing problems 213 7.57 191 6.79

Child age (years) 2,810 8.16 (0.05) 2810 10.67 (0.08)

Gender

Male 1,391 49.50

Female 1,419 50.50

Race

Non-Hispanic black 897 31.92

Non-Hispanic white 388 13.82

Hispanic 1,195 42.54

Other 329 11.72

Primary caregiver

characteristics

Caregiver age, years 2,810 35.58 (0.31) 2810 38.09 (0.29)

Less than high school

education

1059 37.70

Caregiver depression 416 14.82

Caregiver alcohol problem 96 3.43

No live-in partner/spouse 915 32.57 907 32.28

Number in household 2810 5.34 (0.05) 2810 5.22 (0.14)

Note: N values are based on multiply imputed data, and are shown rounded to full numbers. SE standard error for parameter estimates.

POVERTY, FOOD INSECURITY, AND BEHAVIOR

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 447 www.jaacap.org

nalizing problems also met criteria for externalizing

problems. Internalizing and externalizing problems

were signicantly more prevalent among children

who lived in poor households as compared with

nonpoor households (internalizing problems:

22.3% vs. 15.2%, p .0001; externalizing problems:

10.3% vs. 5.7%, p .0001), and among children

who lived in food-insecure households as com-

pared with food-secure households (internalizing

problems: 27.6% vs. 15.4%, p .0001; externalizing

problems: 10.6% vs. 6.7%, p 0.002). Children

exposed to poverty and food insecurity at the same

time had the greatest prevalence of internalizing

problems (30.0%) and externalizing problems

(12.3%) relative to all other groups.

Before examining the prospective associations

among poverty, food insecurity, and childhood

internalizing and externalizing problems, we ex-

amined the baseline associations, adjusted for

child, household, and caregiver characteristics

(child age, gender, race/ethnicity; caregiver age,

cohabitation status, depression, alcohol prob-

lems, education; and number in the household).

In this analysis, poverty status was signicantly

associated with internalizing problems: children

from households below the poverty line were

1.32 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.62) times more likely to

have internalizing problems, relative to children

from households above the poverty line. Poverty

status was also associated with externalizing

problems (prevalence ratio [PR] 1.38, CI 0.99

to 1.92). Children in food insecure households

were 1.49 (95% CI 1.24 to 1.79) times more

likely to have internalizing problems, and 1.47

(95% CI 1.10 to 1.97) times more likely to have

externalizing problems, relative to children in

food secure households.

Internalizing and Externalizing Problems Over the

Follow-Up Period

Internalizing Problems. In the prospective models

adjusted for prior problem status and sociode-

mographic characteristics (Table 2), persistent

poverty was marginally associated with internal-

izing problems at follow-up (PR 1.33, 95% CI

0.99 to 1.77). Movement into poverty status was

not signicantly associated with internalizing

problems, although the effect estimate was in the

expected direction (PR 1.35, 95% CI 0.94 to

1.93). In contrast, there was a signicant associa-

tion between persistent food insecurity and inter-

nalizing problems: children from homes that

were food insecure at baseline and follow-up

(i.e., persistent food insecurity) were 1.56 (95% CI

1.20 to 2.02) times more likely to have inter-

nalizing problems, relative to children from

homes that were never food insecure. Children

from homes that moved from food secure at

baseline to food insecure at follow-up were 1.39

times more likely to have internalizing problems

at follow up, although this association did not

TABLE 2 Estimated Prevalence Ratios (and 95% Condence Intervals) for Internalizing Problems at Follow-up

(N 2,810)

a

Number with

Internalizing

Problems

% with Internalizing

Problems in Each

Category Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Poverty Status

Persistently poor 150 22.38 1.33 (0.99, 1.77) 1.21 (0.89, 1.65)

Previously poor 88 18.94 1.13 (0.84, 1.51) 1.08 (0.80, 1.46)

Newly poor 38 20.62 1.35 (0.94, 1.93) 1.25 (0.87, 1.81)

Never poor 206 13.83 1.00 1.00

Food Insecurity Status

Persistently food insecure 83 31.24 1.56 (1.20, 2.02)** 1.47 (1.12, 1.94)*

Previously food insecure 81 21.26 1.22 (0.93, 1.59) 1.19 (0.90, 1.56)

Newly food insecure 56 22.34 1.39 (0.98, 1.99) 1.37 (0.96, 1.96)

Never food insecure 263 13.72 1.00 1.00

Note: N values are based on multiply imputed data, and are shown rounded to full numbers.

a

In addition to covariates presented, all models adjusted for child characteristics (gender, age, race, and internalizing problems at baseline), caregiver

characteristics (age, education, cohabitation status, depression, and alcohol problem), and number people living in the household. Prevalence ratios

should be interpreted as the increase or decrease in the probability of internalizing or externalizing problems, in comparison to the reference level.

*p 0.05; **p 0.01.

SLOPEN et al.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 448 www.jaacap.org

reach statistical signicance (95% CI 0.98 to

1.99). As shown in model 3, persistent food

insecurity was a signicant predictor of internal-

izing problems at follow-up, even when poverty

trajectory is included in the model (PR 1.47,

95% CI 1.12 to 1.94).

Externalizing Problems. Persistent poverty and

movement into poverty status were not signi-

cantly associated with externalizing problems at

follow-up (Table 3). However, signicant associ-

ations were observed for trajectories of house-

hold food insecurity. Children from homes that

were food insecure at baseline and follow-up

(i.e., that experienced persistent food insecurity)

were 2.11 (95% CI 1.30 to 3.45) times more

likely to have externalizing problems at follow-

up, relative to children from homes that were

never food insecure. In addition, children from

homes that moved from food secure at baseline

to food insecure at follow-up were 1.80 (95% CI

to 1.09 to 2.98) times more likely to have exter-

nalizing problems at follow-up, relative to chil-

dren from homes that were food secure at both

times. The associations between persistent food

insecurity and movement into food insecurity

status with externalizing problems remained sig-

nicant even when trajectory of poverty status

was included in the model (model 3). Of note, a

comparable set of analyses of the continuous

scores for internalizing and externalizing symp-

toms yielded similar results.

Finally, to test the sensitivity of the poverty

threshold used in the prospective analyses, we

reanalyzed the data with the threshold for pov-

erty status set to 130% of the federal poverty line

(the eligibility standard for the federal Supple-

mental Nutrition Assistance Program); in these

analyses, the prevalence ratios were largely

unchanged.

DISCUSSION

The present study used data from two waves of

the PHDCN to investigate associations among

poverty, food insecurity, and child mental health.

Our ndings are of importance from a preven-

tion standpoint, because both poverty and food

insecurity are modiable conditions that can be

addressed through social and economic interven-

tions at the level of the community, state, or

federal government.

33,34

The analyses of baseline

data revealed that children from households be-

low the poverty line were signicantly more

likely to have internalizing problems, and that

children from food insecure households were

signicantly more likely to have internalizing

and externalizing problems, independent of pov-

erty status.

TABLE 3 Estimated Prevalence Ratios (and 95% Condence Intervals) for Externalizing Problems at Follow-up

(N 2,810)

a

Number With

Externalizing

Problems

Percent With

Externalizing

Problems in

Each Category Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Poverty status

Persistently poor 75 11.16 1.37 (0.91, 2.06) 1.17 (0.76, 1.80)

Previously poor 26 5.52 0.88 (0.49, 1.58) 0.83 (0.47, 1.45)

Newly poor 18 9.88 1.31 (0.70, 2.45) 1.21 (0.67, 2.18)

Never poor 72 4.84 1.00 1.00

Food insecurity status

Persistently food insecure 38 14.49 2.11 (1.30, 3.45)** 2.01 (1.21, 3.35)**

Previously food insecure 31 8.20 1.52 (0.91, 2.54) 1.51 (0.88, 2.56)

Newly food insecure 30 11.76 1.80 (1.09, 2.98)* 1.78 (1.07, 2.94)*

Never food insecure 92 4.80 1.00 1.00

Note: N values are based on multiply imputed data, and are shown rounded to full numbers.

a

In addition to covariates presented, all models adjusted for child characteristics (gender, age, race/ethnicity, and externalizing problems at baseline),

caregiver characteristics (age, education, cohabitation status, depression, and alcohol problem), and number of persons living in household. Prevalence

ratios should be interpreted as the increase or decrease in the probability of internalizing or externalizing problems, in comparison to the reference level.

*p 0.05; **p 0.01.

POVERTY, FOOD INSECURITY, AND BEHAVIOR

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 449 www.jaacap.org

In the prospective analysis, although the asso-

ciations were in the expected direction, trajectory

of poverty status did not signicantly predict

internalizing or externalizing problems, control-

ling for prior problem status, and other charac-

teristics. This nding was contrary to our rst

hypothesis and was inconsistent with prior re-

search that has documented an association be-

tween poverty trajectory and change in mental

health.

11,13

These results may differ from previ-

ous research because of study design: our study

included only two waves of data, with approxi-

mately 2 years between data collection, whereas

other studies have had a longer observation

period and/or more frequent assessment and

have used symptom scores rather than diagnostic

outcomes.

11,13,35

Our ndings for the trajectory of

food insecurity provided support for our second

hypothesisnamely, that children who lived in

households that were food insecure at both time

points had a greater likelihood of internalizing

and externalizing problems at follow-up, inde-

pendent of problem status at baseline. The strong

and signicant associations between persistent

food insecurity and internalizing and externaliz-

ing problems after adjustment for poverty status

indicates that the associations between food in-

security and internalizing and externalizing

problems are not confounded by poverty status.

Our pattern of results raises several questions.

In particular, it is noteworthy that household

poverty is signicantly associated with internal-

izing problems and marginally associated with

externalizing problems in the cross-sectional

analysis of the baseline data, but that persistent

poverty or movement into poverty status was not

a statistically signicant predictor of internaliz-

ing or externalizing problems at follow-up. This

inconsistency may be caused by unadjusted con-

founding in the cross-sectional results that is

accounted for in the prospective analyses by

control of prior internalizing or externalizing

problem status. Alternatively, it could also be

linked to length of follow-up. It is also challeng-

ing to reconcile our ndings that trajectory of

food insecurity is predictive of internalizing and

externalizing problems at follow-up, yet trajec-

tory of poverty status is not. It is possible that

food insecurity is a more proximal measure of

stress load in the household, which may ulti-

mately lead to the associations we observe. Fi-

nally, it is puzzling that caregiver depression

(measured at baseline) is a signicant predictor

of internalizing and externalizing problems at

baseline but not at follow-up; this may suggest

that the effects of caregiver depression on child

outcomes are largely contemporaneous in nature,

rather than persisting over the long term. Unfor-

tunately, we are unable to examine the associa-

tion between caregiver depression at follow-up

and behavior at follow-up because we do not

have a usable measure of caregiver depression at

this time.

Several mechanisms may explain the associ-

ations between food insecurity and mental

health problems that we observed. Food and

nutrition are important aspects of daily life;

psychologically, routines involving food are

important for the childs comfort and feelings

of security. Moreover, all individuals in the

household are potentially affected by food in-

security; therefore mental and physical well-

being of family members may be compromised,

which may have an impact on familial efcacy

for a wide range of activities.

9

In addition, food

insecurity may have negative consequences for

a childs nutrient balance and physical health,

as well as cognitive and academic outcomes,

which place children at risk for the develop-

ment of behavior problems.

9,36

Each of these

potential mechanisms represents an important

direction for future research.

The ndings for this study should be consid-

ered in the context of several limitations. First,

household food insecurity was measured using a

single dichotomous question; this crude measure

is not able to capture the full extent of food

insecurity that a child has experienced, and does

not measure child hunger experiences. However,

within our data, this single-item measure is

strongly correlated with caregiver report of cut-

ting meal sizes, which indicates a lack of food

available to members in the household. Evidence

suggests that even slight forms of food insecurity

and undernutrition can have lasting effects;

37

therefore we believe that the available measure is

a useful, albeit imperfect, indicator. Second, our

study is limited by incomplete data and loss to

follow-up. We controlled for variables associated

with attrition, which should prevent bias; in

addition, we used multiple imputation to pre-

serve the original sample composition. Third, the

federal poverty line is not specic to region or

urban/rural location; it is possible that the pov-

erty line does not accurately represent the

amount of money that a family requires to be

SLOPEN et al.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 450 www.jaacap.org

self-sufcient in an urban area such as Chicago.

As a result, some individuals categorized as

nonpoor might meet criteria for poor if the

threshold was adjusted for city-specic costs of

living. However, as noted in the results section,

our sensitivity analysis indicated that the results

were largely unchanged when we altered the

threshold for poverty status. Fourth, our mea-

sures of internalizing and externalizing problems

are limited to caregiver report; these ratings may

be biased as the result of caregiver mental health.

Although some researchers have hypothesized

that depressed mothers report distorted percep-

tions of childrens behavior, a review on this

topic did not nd evidence to support this hy-

pothesis.

38

Nevertheless, to rule out this possibil-

ity, we repeated our analyses excluding children

that had caregivers with major depression at

baseline; our ndings remain largely the same.

Finally, although we adjusted for a broad set of

caregiver characteristics, it is important to con-

sider the possibility that unmeasured factors re-

lated to parenting characteristics may predict

both food insecurity and psychological symp-

toms in children. The above limitations highlight

the need for additional prospective research that

includes frequent and detailed measures of chil-

dren and caregivers.

39

The present study has several implications for

understanding the etiology of child psychiatric

disorders, given that CBCL scores converge with

DSM psychiatric diagnoses and reect substan-

tial psychopathology.

23,24

This set of ndings

contributes to our understanding about the etiol-

ogy of childhood disorders, as it demonstrates

that (a) continued exposure to household food

insecurity is predictive of internalizing and ex-

ternalizing problems, and (b) excess risk for

internalizing and externalizing disorders is not

discernible among children who lived in house-

holds that were food insecure at baseline and

then became food secure at follow-up. This sug-

gests that interventions that alleviate household

poverty and food insecurity among families ex-

periencing these conditions may be effective in

reducing the prevalence of childhood behavior

problems. Our ndings illustrate the importance

of screening children and caregivers about their

access to food within the clinical setting, and

developing an infrastructure to connect clients

with nutritional resources (e.g., Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP], food pan-

tries) when household food insecurity is present.

Our results suggest that in addition to fullling a

physical need, food has an important role in

psychological well-being; therefore, food insecu-

rity may be an important trait for clinicians to

assess, as it may have a role in the development

of behavioral problems.

In conclusion, poverty and food insecurity are

risk factors that can be targeted for intervention.

An example of a successful poverty intervention

is the Minnesota Family Investment Program.

34

This program has demonstrated that increased

employment rates and small increases in income

for working poor parents can reduce child pov-

erty and lead to reductions in externalizing prob-

lems among children. Research has also docu-

mented that the Food Stamp Program (now

referred to as SNAP) and the Special Supplement

Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Chil-

dren are able to increase nutrient intake among

low income children.

39

Additional research is

required to expand our ability to effectively pro-

vide adequate nutrition to children and families

that have poor access to high-quality foods, and

to improve our understanding of adequate nu-

trition in relation to child mental health. In

summary, our ndings provide evidence for a

prospective association between food insecurity

and increased risk for internalizing and external-

izing problems. This study highlights the impor-

tance of efforts to develop and strengthen pro-

grams that protect vulnerable families from the

experiences and consequences of poverty and

food insecurity. &

Accepted February 16, 2010.

Ms. Slopen and Drs. Fitzmaurice, Williams, and Gilman are with the

Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Williams is also with Harvard

University.

This work was supported by a doctoral research award from the

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Award 200610MDR-

168591-163832).

Disclosure: Ms. Slopen and Drs. Fitzmaurice, Williams, and Gilman

report no biomedical nancial interests or potential conicts of interest.

Correspondence to Natalie Slopen: Department of Society, Human

Development, and Health, Harvard School of Public Health, 677

Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: nslopen@hsph.

harvard.edu

0890-8567/10/2010 American Academy of Child and Adoles-

cent Psychiatry

DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.018

POVERTY, FOOD INSECURITY, AND BEHAVIOR

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 451 www.jaacap.org

REFERENCES

1. Hein CM, Siefert K, Williams DR. Food insufciency and

womens mental health: ndings from a 3-year panel of welfare

recipients. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1971-1982.

2. Whitaker RC, Phillips SM, Orzol SM. Food insecurity and the risks

of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their

preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e859-e868.

3. Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG. Children of affec-

tively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child

Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1134-1141.

4. Heseker H, Kubler W, Pudel V, et al. Psychological disorders as

early symptoms of a mild-to-moderate vitamin deciency. Ann N

Y Acad Sci. 1992;669:352-357.

5. Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Hagen J, et al. Poorer behavioral and

developmental outcome more than 10 years after treatment for

iron deciency in infancy. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E51.

6. Bishaw A, Semega J. American Community Survey Reports,

ACS-09, Income, Earnings, and Poverty Data from the 2007

American Community Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Census

Bureau, U.S. Government Printing Ofce; 2008.

7. Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S. Measuring Food Security in the

United States: Household Food Security in the United States,

2005. Washington, DC: USDA Economic Research Service. Eco-

nomic Research Report No. 29; 2007.

8. Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children.

Future Child. 1997;7:55-71.

9. Ashiabi GS, ONeal KK. A framework for understanding the

association between food insecurity and childrens developmen-

tal outcomes. Child Develop Perspect. 2008;2:71-77.

10. Bor W, Najman JM, Andersen MJ, et al. The relationship between

low family income and psychological disturbance in young

children: an Australian longitudinal study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry.

1997;31:664-675.

11. Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, et al. Relationships between

poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. J Am Med

Assoc. 2003;290:2023-2029.

12. Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation

and early child development. Child Dev. 1994;65:296-318.

13. McLeod JD, Shanahan MJ. Trajectories of poverty and childrens

mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 1996;37:207-220.

14. Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Family food insufciency, but

not low family income, is positively associated with dysthymia

and suicide symptoms in adolescents. J Nutr. 2002;132:719-725.

15. Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA, Jr.Food insufciency and

American school-aged childrens cognitive, academic, and psy-

chosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108:44-53.

16. Cook JT, Frank DA. Food security, poverty, and human develop-

ment in the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:193-209.

17. Murphy JM, Wehler CA, Pagano ME, et al. Relationship between

hunger and psychosocial functioning in low-income American

children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:163-170.

18. Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household food

insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler develop-

ment. Pediatrics. 2008;121:65-72.

19. Weinreb L, Wehler C, Perloff J, et al. Hunger: its impact on

childrens health and mental health. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e41.

20. Jyoti DF, Frongillo EA, Jones SJ. Food insecurity affects school

childrens academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. J

Nutr. 2005;135:2831-2839.

21. Earls F, Buka SL. Project on Human Development in Chicago

Neighborhoods. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice;

1997.

22. Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18

and 1991 Prole. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry,

University of Vermont; 1991.

23. Kasius MC, Ferdinand RF, van den Berg H, et al. Associations

between different diagnostic approaches for child and adolescent

psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:625-632.

24. Ferdinand RF. Validity of the CBCL/YSR DSM-IV scales anxiety

problems and affective problems. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:126-

134.

25. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Man-

ual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III-R. Washington, DC: American

Psychiatric Association; 1987.

26. Kleinman RE, Murphy JM, Wieneke KM, et al. Use of a single-

question screening tool to detect hunger in families attending a

neighborhood health center. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:278-284.

27. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen H. The

World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic

Interview short-form (CIDI-SF). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res.

1998;7:171-185.

28. Selzer ML, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short

Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST). J Stud Alcohol.

1975;36:117-126.

29. McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, et al. Estimating the relative risk in

cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J

Epidemiol. 2003;157:940-943.

30. Zou G. A modied Poisson regression approach to prospective

studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702-706.

31. Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or

prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199-

200.

32. Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, et al. A multi-

variate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a

sequence of regression models. Survey Methodol. 2001;27:85-95.

33. Siefert K, Finlayson TL, Williams DR, et al. Modiable risk and

protective factors for depressive symptoms in low-income Afri-

can American mothers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:113-123.

34. Gennetian LA, Miller C. Children and welfare reform: a view

from an experimental welfare program in Minnesota. Child Dev.

2002;73:601-620.

35. Dearing E, McCartney K, Taylor BA. Change in family income-

to-needs matters more for children with less. Child Dev. 2001;72:

1779-1793.

36. Skalicky A, Meyers AF, Adams WG, et al. Child food insecurity

and iron deciency anemia in low-income infants and toddlers in

the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:177-185.

37. Chilton M, Chyatte M, Breauz J. The negative effects of poverty

and food insecurity on child development. Indian J Med Res.

2007;126:262-272.

38. Richters JE. Depressed mothers as informants about their chil-

dren: a critical review of the evidence for distortion. Psychol Bull.

1992;112:485-499.

39. Rose D, Habicht JP, Devaney B. Household participation in the

Food Stamp and WIC programs increases the nutrient intakes of

preschool children. J Nutr. 1998;128:548-555.

SLOPEN et al.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

VOLUME 49 NUMBER 5 MAY 2010 452 www.jaacap.org

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- 2022 WR Extended VersionDocument71 pages2022 WR Extended Versionpavankawade63Pas encore d'évaluation

- Configuring BGP On Cisco Routers Lab Guide 3.2Document106 pagesConfiguring BGP On Cisco Routers Lab Guide 3.2skuzurov67% (3)

- PC Model Answer Paper Winter 2016Document27 pagesPC Model Answer Paper Winter 2016Deepak VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- Injections Quiz 2Document6 pagesInjections Quiz 2Allysa MacalinoPas encore d'évaluation

- YIC Chapter 1 (2) MKTDocument63 pagesYIC Chapter 1 (2) MKTMebre WelduPas encore d'évaluation

- Siemens Make Motor Manual PDFDocument10 pagesSiemens Make Motor Manual PDFArindam SamantaPas encore d'évaluation

- Core ValuesDocument1 pageCore ValuesIan Abel AntiverosPas encore d'évaluation

- Skills Checklist - Gastrostomy Tube FeedingDocument2 pagesSkills Checklist - Gastrostomy Tube Feedingpunam todkar100% (1)

- Determination Rules SAP SDDocument2 pagesDetermination Rules SAP SDkssumanthPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes:: Reinforcement in Manhole Chamber With Depth To Obvert Greater Than 3.5M and Less Than 6.0MDocument1 pageNotes:: Reinforcement in Manhole Chamber With Depth To Obvert Greater Than 3.5M and Less Than 6.0Mسجى وليدPas encore d'évaluation

- Fds-Ofite Edta 0,1MDocument7 pagesFds-Ofite Edta 0,1MVeinte Años Sin VosPas encore d'évaluation

- MMS - IMCOST (RANJAN) Managing Early Growth of Business and New Venture ExpansionDocument13 pagesMMS - IMCOST (RANJAN) Managing Early Growth of Business and New Venture ExpansionDhananjay Parshuram SawantPas encore d'évaluation

- B I o G R A P H yDocument17 pagesB I o G R A P H yRizqia FitriPas encore d'évaluation

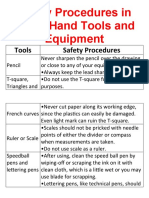

- Safety Procedures in Using Hand Tools and EquipmentDocument12 pagesSafety Procedures in Using Hand Tools and EquipmentJan IcejimenezPas encore d'évaluation

- PDFDocument10 pagesPDFerbariumPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 13 (Automatic Transmission)Document26 pagesChapter 13 (Automatic Transmission)ZIBA KHADIBIPas encore d'évaluation

- Shakespeare Sonnet EssayDocument3 pagesShakespeare Sonnet Essayapi-5058594660% (1)

- Disassembly Procedures: 1 DELL U2422HB - U2422HXBDocument6 pagesDisassembly Procedures: 1 DELL U2422HB - U2422HXBIonela CristinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Monologues PDFDocument5 pagesSample Monologues PDFChristina Cannilla100% (1)

- Amount of Casien in Diff Samples of Milk (U)Document15 pagesAmount of Casien in Diff Samples of Milk (U)VijayPas encore d'évaluation

- What's New in CAESAR II: Piping and Equipment CodesDocument1 pageWhat's New in CAESAR II: Piping and Equipment CodeslnacerPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Post - Exploring The Intersection of Work and Well-Being - A Guide To Occupational Health PsychologyDocument3 pagesHealth Post - Exploring The Intersection of Work and Well-Being - A Guide To Occupational Health PsychologyihealthmailboxPas encore d'évaluation

- Apron CapacityDocument10 pagesApron CapacityMuchammad Ulil AidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Congenital Cardiac Disease: A Guide To Evaluation, Treatment and Anesthetic ManagementDocument87 pagesCongenital Cardiac Disease: A Guide To Evaluation, Treatment and Anesthetic ManagementJZPas encore d'évaluation

- Toeic: Check Your English Vocabulary ForDocument41 pagesToeic: Check Your English Vocabulary ForEva Ibáñez RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 1 SBL NotesDocument13 pagesCHAPTER 1 SBL NotesPrieiya WilliamPas encore d'évaluation

- Recitation Math 001 - Term 221 (26166)Document36 pagesRecitation Math 001 - Term 221 (26166)Ma NaPas encore d'évaluation

- Micro EvolutionDocument9 pagesMicro EvolutionBryan TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Radon-222 Exhalation From Danish Building Material PDFDocument63 pagesRadon-222 Exhalation From Danish Building Material PDFdanpalaciosPas encore d'évaluation

- Government College of Nursing Jodhpur: Practice Teaching On-Probability Sampling TechniqueDocument11 pagesGovernment College of Nursing Jodhpur: Practice Teaching On-Probability Sampling TechniquepriyankaPas encore d'évaluation