Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Ordinary Affects by Kathleen Stewart

Transféré par

rajah418100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

76 vues3 pagesReview Kathleen Stewart Ordinary Affect

Titre original

OrdinaryAffects Review

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentReview Kathleen Stewart Ordinary Affect

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

76 vues3 pagesOrdinary Affects by Kathleen Stewart

Transféré par

rajah418Review Kathleen Stewart Ordinary Affect

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 3

Ordinary Affects by Kathleen Stewart

Reviewed by Kate Eichhorn

In Ordinary Affects, anthropologist Kathleen Stewart explores everyday lifes surging

affects (9) through a series of poetic fieldnotes. But this is not a book about knowing

everyday subjects and objects, nor the spaces they inhabit but rather an enactment of the

intensity and texture of the ordinary and the feelings it evokes. Stewart wisely rejects

the discursive norms of her discipline there are few citations and no diagrams.

Appropriately, Ordinary Affects is a deeply vernacular text.

At times, there is a surprising beauty in the texture of Stewarts accounts of everyday

forms, flows, powers, pleasures, encounters, distractions, drudgery (29). More often,

the texture is thread-bear and soiled. After reading the book, I am compelled to repeat her

stories. Most of what I remember is ugly and abject, like the story about the handsome

young man in the mechanics uniform at the Walgreens who covers his mouth when he

speaks nothing can conceal his misshapen teeth. The image sticks because we share his

embarrassment. But is it pity or repulsion we feel when Stewart tells us about the

destitute handyman who sets out to cohabitate with his ex girlfriends paraplegic

daughter, assuming she will be happy to take in any man who arrives on her doorstep?

Feelings bind subjects to objects and here, as in everyday life, disgust proves especially

sticky.

Stewarts stories spill over and threaten to contaminate both proper scholarly writing and

any pretense of a stable American way of life. In Ordinary Affects, the homeless camp

and trailer park are never far off, and the author, an associate professor of Anthropology

at the University of Texas, rarely steps foot on campus. Like everyone else, shes too

busy standing in line at the Target and Foodland buying vacuum cleaner bags and crib

sheets and chasing her daughter up and down the aisles. Everyday labours, joys and

necessities interrupt her investigation at every turn but they also keep it on track.

By the time Stewart drags us into the Utopian Hotel on page 85, weve started to relax

our judgment. The refrigerator stocked full of ordinary frozen dinners in the hotel

lobby may be a chilling vault of disgusting trans fats, or a symbol of mass production and

excess consumption, but were with Stewart on this journey into the everyday, so the

frozen dinners, like the people running the hotel, are strangely gracious and homey

just part of a way of doing things differently. For the same reason, there is no need for

suspicion when the guy at the toll booth pays for the next car in line sometimes people

are just decent. Whats wrong with that?

In Ordinary Affects, stress is palpable. People are stockpiling cases of coke, pumping

their bodies full of health shakes, and shuttling their families off to gated communities. If

Free-floating affects lodge in the surface tension of stress, loneliness, dread, yearning

(94), this book is written from the ground of a nation in crisis. But reading Stewarts

fieldnotes on American life, the familiar also begins to look a little different. Through her

attentiveness to the everyday, she offers a deeply political commentary refreshingly free

of didacticism. In a brief introduction, which is marked by a familiar scholarly style of

writing that seems strangely misaligned with her overall project, Stewart acknowledges

that Ordinary Affects is concerned with neoliberalism, advanced capitalism and

globalization, but explains that it is an experiment, not a judgment (i). But is her

experiment effective?

As one reads through Stewarts successive entries, ranging in length from a few sentences

to three or four pages, repeated themes, words and images begin to create patterns of

recognition and force the books subtle argument to the surface. Not surprisingly, many

of her entries take place in and around the edges of department stores and malls. This is

America. Shopping is part of the fabric of everyday life. Malls are monuments to the

nations bloated consumerism. But in life, contradictions are commonplace, so Stewarts

malls arent simply symbols of excess but also contact zones places where people meet,

form communities, swap familiar comforts. Even the RVers who congregate in Wal-Mart

parking lots to refuel, stock up and sleep are given their due respect. A compelling

geriatric subculture, the RVers brazenly shop without a conscience in an era when it is

difficult to ignore the politics of shopping. But are these elderly nomads evil or simply

distracted too distracted to notice the employees locked inside the Wal-Mart all night or

the whirl-marters on non-shopping sprees all day? If you approach Stewarts series

of poetic fieldnotes looking for a critical commentary on neoliberalism, advanced

capitalism or globalization, her depiction of these gas-guzzling retirees may appear too

generous. However, where there is community and contradiction, is there not also the

potential for change? Such lingering questions appear to be what Stewarts experiment

is all about.

All her life shes been yelling Pay attention! but now shes not so sure thats such a

good idea. Hypervigilance has taken root. But these are not the fieldnotes of a paranoid

who has chosen to hunker down in a house buttressed with surveillance cameras and

fortified with supplies for the next big attack. It is the distracted that Stewart seeks to

challenge, and she does so simply by adopting a method rooted in a practice of everyday

life collecting.

As she observes in one of the books briefest fieldnotes, when people collect found

objects snatched off the literal or metaphorical side of the road.all kinds of other things

are happening too (21). This succinct methodological statement reminds us that

collecting is never simply an act of accumulation. Like Benjamins Arcades Project,

which Stewart cites as one source of inspiration for her much more modest undertaking,

Ordinary Affects transfigures the most banal practices and objects by juxtaposing them to

cast new constellations. Stewarts ability to produce moments of illuminating tension

through the careful arrangement of her fieldnotes may not express a single argument nor

offer a definitive judgment on American life in the new millennium, but it does produce

both shock and reflection in the reader. And somewhere between the thick description of

the fieldnote and the flow of the poetic line, she wakes us up again and again to the

realization that in order to even begin understanding whats going on, we must first

simply take notice.

Kate Eichhorn is the author of Fond (BookThug, 2008) and the co-editor of Canadian

Innovative Womens Poetry and Poetics (forthcoming from Coach House Books in

2009). She is an assistant professor of Culture and Media Studies at The New School.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Performances of Sacred Places: Crossing, Breathing, ResistingD'EverandThe Performances of Sacred Places: Crossing, Breathing, ResistingSilvia BattistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Behar and Mannheim Couple in Cage Visual Anthropology Review 1995aDocument10 pagesBehar and Mannheim Couple in Cage Visual Anthropology Review 1995aanatecarPas encore d'évaluation

- Dance Fase QuadDocument20 pagesDance Fase QuadLenz21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Octave Mirbeau: Two Plays - Business Is Business & CharityD'EverandOctave Mirbeau: Two Plays - Business Is Business & CharityPas encore d'évaluation

- Experiments in Imagining Otherwise (Lola Olufemi)Document160 pagesExperiments in Imagining Otherwise (Lola Olufemi)flxnmzPas encore d'évaluation

- Senses of Upheaval: Philosophical Snapshots of a DecadeD'EverandSenses of Upheaval: Philosophical Snapshots of a DecadePas encore d'évaluation

- POGGIOLI, Renato. "The Concept of A Movement." The Theory of The Avant-Garde 1968Document13 pagesPOGGIOLI, Renato. "The Concept of A Movement." The Theory of The Avant-Garde 1968André CapiléPas encore d'évaluation

- Window Shopping: Cinema and the PostmodernD'EverandWindow Shopping: Cinema and the PostmodernÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (2)

- Bourriaud Relational AestheticsDocument18 pagesBourriaud Relational AestheticsLucie BrázdováPas encore d'évaluation

- Lisa Robertson PDFDocument21 pagesLisa Robertson PDFargsuarez100% (1)

- Artistic ResearchDocument6 pagesArtistic Researchdivyvese1100% (1)

- Paolo Virno, 'Post-Fordist Semblance'Document6 pagesPaolo Virno, 'Post-Fordist Semblance'dallowauPas encore d'évaluation

- Red Art New Utopias in Data CapitalismDocument250 pagesRed Art New Utopias in Data CapitalismAdam C. PassarellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kleist - On The Marionette TheaterDocument6 pagesKleist - On The Marionette TheaterAlejandro AcostaPas encore d'évaluation

- (Breaking Feminist Waves) Henriette Gunkel, Chrysanthi Nigianni, Fanny Söderbäck - Undutiful Daughters - New Directions in Feminist Thought and Practice-Palgrave Macmillan (2012)Document245 pages(Breaking Feminist Waves) Henriette Gunkel, Chrysanthi Nigianni, Fanny Söderbäck - Undutiful Daughters - New Directions in Feminist Thought and Practice-Palgrave Macmillan (2012)Αθηνά Γεωργία ΚουμελάPas encore d'évaluation

- Deleuze-Spinoza and UsDocument7 pagesDeleuze-Spinoza and UsElizabeth MartínezPas encore d'évaluation

- Lacan A Love LetterDocument13 pagesLacan A Love LetterborismalinovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Emancipated Spectator - Boal RanciereDocument14 pagesEmancipated Spectator - Boal RanciereLuka RomanovPas encore d'évaluation

- Brandon Labelle Interview by Anna RaimondoDocument32 pagesBrandon Labelle Interview by Anna RaimondomykhosPas encore d'évaluation

- Balzac GaitDocument7 pagesBalzac Gaithieratic_headPas encore d'évaluation

- Simon Sheikh: Spaces For Thinking. 2006Document8 pagesSimon Sheikh: Spaces For Thinking. 2006Miriam Craik-HoranPas encore d'évaluation

- ZJJ 3Document23 pagesZJJ 3jananiwimukthiPas encore d'évaluation

- Robert Walser - Frau BähniDocument5 pagesRobert Walser - Frau BähniOCorpoNegroPas encore d'évaluation

- Concrete Poetry As An International Movement Viewed by Augusto de CamposDocument12 pagesConcrete Poetry As An International Movement Viewed by Augusto de CamposPaulo MoreiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Feuer, Jane - The Self-Reflexive Musical and The Myth of EntertainmentDocument9 pagesFeuer, Jane - The Self-Reflexive Musical and The Myth of Entertainmentpedrovaalcine100% (1)

- Skin Culture and Psychoanalysis-IntroDocument15 pagesSkin Culture and Psychoanalysis-IntroAnonymous Dgn6TCsbB100% (1)

- A Savage PerformanceDocument17 pagesA Savage PerformanceHafidza CikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Interview - Johann Kresnik - TANZFONDSDocument5 pagesInterview - Johann Kresnik - TANZFONDSodranoel2014Pas encore d'évaluation

- On Falling: A Study Room Guide On Live Art & FallingDocument22 pagesOn Falling: A Study Room Guide On Live Art & FallingthisisLiveArtPas encore d'évaluation

- Ight of Real TearsDocument222 pagesIght of Real Tearsmichael_berenbaum100% (1)

- Latour's 15 ModesDocument2 pagesLatour's 15 ModesTerence Blake100% (2)

- Clemena Antonova, How Modernity Invented Tradition PDFDocument7 pagesClemena Antonova, How Modernity Invented Tradition PDFLudovico Da FeltrePas encore d'évaluation

- Eric Alliez PDFDocument2 pagesEric Alliez PDFBrendaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lusi PDFDocument19 pagesLusi PDFجو ترزيتشPas encore d'évaluation

- Deleuze and GuattariDocument24 pagesDeleuze and GuattariMuhammad Tahir Pervaiz100% (1)

- Global Art and Politics of Mobility TranDocument39 pagesGlobal Art and Politics of Mobility TranTadeu RibeiroPas encore d'évaluation

- Performing Research - Sibylle PetersDocument23 pagesPerforming Research - Sibylle PetersthisisLiveArtPas encore d'évaluation

- Sarat Maharaj Method PDFDocument11 pagesSarat Maharaj Method PDFmadequal2658Pas encore d'évaluation

- Memory Deleuze TDocument16 pagesMemory Deleuze TCosmin Bulancea100% (1)

- Philosophers - Tone - PDF Harry PartchDocument21 pagesPhilosophers - Tone - PDF Harry PartchChris F OrdlordPas encore d'évaluation

- Interview With Mladen DolarDocument10 pagesInterview With Mladen DolarAkbar HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- Berlin ChronicleDocument301 pagesBerlin ChronicleLaila Melchior100% (1)

- Against Dead TimeDocument16 pagesAgainst Dead TimethlroPas encore d'évaluation

- HaackeDocument30 pagesHaackespamqyrePas encore d'évaluation

- The Stage and The Carnival (Romanian Theatre Aafter Ccensorship)Document214 pagesThe Stage and The Carnival (Romanian Theatre Aafter Ccensorship)adigpopPas encore d'évaluation

- AN Anthropology OF Contemporary ART: Practices, Markets, and CollectorsDocument22 pagesAN Anthropology OF Contemporary ART: Practices, Markets, and CollectorsChristina GrammatikopoulouPas encore d'évaluation

- Chance and Indeterminacy As Curatorial StrategiesDocument20 pagesChance and Indeterminacy As Curatorial StrategiesjessicaberlangaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Essay On Stage: Singularity and PerformativityDocument15 pagesThe Essay On Stage: Singularity and PerformativitySlovensko Mladinsko Gledališče ProfilPas encore d'évaluation

- Decolonizing Curatorial Lepeck FF PDFDocument16 pagesDecolonizing Curatorial Lepeck FF PDFNicolas Licera VidalPas encore d'évaluation

- Karl Ove Knausgård's Acceptence SpeechDocument15 pagesKarl Ove Knausgård's Acceptence SpeechAlexander SandPas encore d'évaluation

- Potaznik ThesisDocument34 pagesPotaznik ThesisItzel YamiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Etienne Souriau - Time in The Plastic Arts PDFDocument15 pagesEtienne Souriau - Time in The Plastic Arts PDFDaniel Bozhich100% (1)

- Pina BauschDocument22 pagesPina BauschQuattro Quattro Sei100% (1)

- Nature's Nocturnal Services - Light Pollution As A Non-Recognised Challenge For Ecosystem Services Research and ManagementDocument5 pagesNature's Nocturnal Services - Light Pollution As A Non-Recognised Challenge For Ecosystem Services Research and ManagementTuấn Anh PhạmPas encore d'évaluation

- Décor Marcel BroodthaersDocument20 pagesDécor Marcel BroodthaerseurostijlPas encore d'évaluation

- CHRISTIANSEN, Steen - Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis RevisitedDocument191 pagesCHRISTIANSEN, Steen - Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis RevisitedtibacanettiPas encore d'évaluation

- Icolas Bourriaud Postproduction Culture As Screenplay: How Art Reprograms The WorldDocument47 pagesIcolas Bourriaud Postproduction Culture As Screenplay: How Art Reprograms The Worldartlover30Pas encore d'évaluation

- Erasure in ArtDocument14 pagesErasure in Artjerome2ndPas encore d'évaluation

- 2015-10-15 Notes On Agamben - Resistance in ArtDocument2 pages2015-10-15 Notes On Agamben - Resistance in ArtFranz Williams100% (1)

- Visions of KingshipDocument40 pagesVisions of KingshipShailka MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Curtis Bir AnDocument15 pagesCurtis Bir AnVal CurtisPas encore d'évaluation

- Latam Mrosummit 2014-1-24Document13 pagesLatam Mrosummit 2014-1-24rajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Netra TantraDocument27 pagesNetra Tantrarajah41863% (8)

- When The Hindu Goddess Moves To DenmarkDocument8 pagesWhen The Hindu Goddess Moves To Denmarkrajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Doniger On Kama SutraDocument4 pagesDoniger On Kama Sutrarajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elizabeth Sharpe - The Secrets of The Kaula CircleDocument104 pagesElizabeth Sharpe - The Secrets of The Kaula Circlewagnerjoseph4079100% (1)

- Blavatsky Archive - 1906 CommitteDocument33 pagesBlavatsky Archive - 1906 Committerajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bankside Urban ForestDocument53 pagesBankside Urban Forestrajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Annie Besand and The Moral Code - A ProtestDocument22 pagesAnnie Besand and The Moral Code - A Protestrajah418100% (1)

- PukaarDocument28 pagesPukaarrajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Besant Lead Beater Letters Full 2Document5 pagesBesant Lead Beater Letters Full 2rajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gregory Tillet Chapters 1-3Document123 pagesGregory Tillet Chapters 1-3rajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Invisible ManDocument18 pagesInvisible Manrajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study Clickability NetAppDocument2 pagesCase Study Clickability NetAppphil_hinePas encore d'évaluation

- WyvernDocument1 pageWyvernrajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Xpress Math XTN User GuideDocument158 pagesXpress Math XTN User Guiderajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aircraft Finance Guide 2012Document132 pagesAircraft Finance Guide 2012rajah418100% (1)

- Hypotheses On The Orphic CircleDocument7 pagesHypotheses On The Orphic Circlerajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Herbert Tucker's "The Fix of Form: An Open Letter"Document6 pagesHerbert Tucker's "The Fix of Form: An Open Letter"rajah418Pas encore d'évaluation

- Greenwood Tarot Book ChescaDocument39 pagesGreenwood Tarot Book Chescarajah418100% (8)

- Lion Air Eticket Itinerary / ReceiptDocument2 pagesLion Air Eticket Itinerary / Receipthalil ariantoPas encore d'évaluation

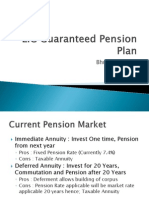

- LIC Guaranteed HNI Pension PlanDocument9 pagesLIC Guaranteed HNI Pension PlanBhushan ShethPas encore d'évaluation

- BRAC Bank Limited - Cards P@y Flex ProgramDocument3 pagesBRAC Bank Limited - Cards P@y Flex Programaliva78100% (2)

- Math2 q1 Week 6 Day1-5Document98 pagesMath2 q1 Week 6 Day1-5zshaninajeorahPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 18 Multiple Choice Answers With ExplanationDocument10 pagesCHAPTER 18 Multiple Choice Answers With ExplanationClint-Daniel Abenoja75% (4)

- Investment Climate Brochure - Ethiopia PDFDocument32 pagesInvestment Climate Brochure - Ethiopia PDFR100% (1)

- F15F16Document1 pageF15F16MinamPeruPas encore d'évaluation

- Free Market CapitalismDocument18 pagesFree Market CapitalismbalathekickboxerPas encore d'évaluation

- Philexport CMTA Update 19sept2017Document15 pagesPhilexport CMTA Update 19sept2017Czarina Danielle EsequePas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Barcelona Metropolitan Strategic PlanDocument42 pages1st Barcelona Metropolitan Strategic PlanTbilisicds GeorgiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaction PaperDocument13 pagesReaction PaperPhilip CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Super Final Applied Economics First Periodical ExamDocument4 pagesSuper Final Applied Economics First Periodical ExamFrancaise Agnes Mascariña100% (2)

- Population: Basic Statistics: We Are Continuing To GrowDocument4 pagesPopulation: Basic Statistics: We Are Continuing To GrowarnabnitwPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Options For Building CompetitivenessDocument53 pagesStrategic Options For Building Competitivenessjeet_singh_deepPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Form BDFSDDocument44 pages3 Form BDFSDMaulik RavalPas encore d'évaluation

- SAP S 4 HANA FI 1610 Overview Mindmap Edition PDFDocument2 pagesSAP S 4 HANA FI 1610 Overview Mindmap Edition PDFkamranahmedaslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Challenges and Opportunities For Regional Integration in AfricaDocument14 pagesChallenges and Opportunities For Regional Integration in AfricaBOUAKKAZ NAOUALPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Culture in Russia: Budui Ana-MariaDocument10 pagesBusiness Culture in Russia: Budui Ana-Mariahelga_papp5466Pas encore d'évaluation

- Flight Ticket - Ahmedabad To MumbaiDocument2 pagesFlight Ticket - Ahmedabad To Mumbaieva guptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Singpapore Companies Data (Extracted 14 April 2020)Document114 pagesSingpapore Companies Data (Extracted 14 April 2020)Irene LyePas encore d'évaluation

- Group 9 Design by Kate Case Analysis PDFDocument7 pagesGroup 9 Design by Kate Case Analysis PDFSIMRANPas encore d'évaluation

- Asg1 - Nagakin Capsule TowerDocument14 pagesAsg1 - Nagakin Capsule TowerSatyam GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bankura TP ListDocument16 pagesBankura TP ListDeb D Creative StudioPas encore d'évaluation

- Records - POEA PDFDocument1 pageRecords - POEA PDFTimPas encore d'évaluation

- OSCM-IKEA Case Kel - 1 UpdateDocument29 pagesOSCM-IKEA Case Kel - 1 UpdateOde Majid Al IdrusPas encore d'évaluation

- Peri Up Flex Core ComponentsDocument50 pagesPeri Up Flex Core ComponentsDavid BourcetPas encore d'évaluation

- Universal Remote SUPERIOR AIRCO 1000 in 1 For AirCoDocument2 pagesUniversal Remote SUPERIOR AIRCO 1000 in 1 For AirCoceteganPas encore d'évaluation

- CIBP Projects and Working Groups PDFDocument37 pagesCIBP Projects and Working Groups PDFCIBPPas encore d'évaluation

- Rex 3e Level 4 - Unit 6Document10 pagesRex 3e Level 4 - Unit 677Pas encore d'évaluation

- Script For EconomicsDocument5 pagesScript For EconomicsDen mark RamirezPas encore d'évaluation