Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Public Choice Volume 23 Issue 1 1975 (Doi 10.1007/bf01718099) James M. Buchanan - Utopia, The Minimal State, and Entitlement PDF

Transféré par

vald7770 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

32 vues6 pagesA review of Robert Nozick's book, "anarchy, state, and utopia" by james m. Buchanan-k. Nozick treats three topics that are superficially distinct but closely related at a more fundamental level of analysis. A framework for a utopian framework is familiar, attractive, and hopefully convincing, he says.

Description originale:

Titre original

Public Choice Volume 23 issue 1 1975 [doi 10.1007%2Fbf01718099] James M. Buchanan -- Utopia, the minimal state, and entitlement (1).pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentA review of Robert Nozick's book, "anarchy, state, and utopia" by james m. Buchanan-k. Nozick treats three topics that are superficially distinct but closely related at a more fundamental level of analysis. A framework for a utopian framework is familiar, attractive, and hopefully convincing, he says.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

32 vues6 pagesPublic Choice Volume 23 Issue 1 1975 (Doi 10.1007/bf01718099) James M. Buchanan - Utopia, The Minimal State, and Entitlement PDF

Transféré par

vald777A review of Robert Nozick's book, "anarchy, state, and utopia" by james m. Buchanan-k. Nozick treats three topics that are superficially distinct but closely related at a more fundamental level of analysis. A framework for a utopian framework is familiar, attractive, and hopefully convincing, he says.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 6

Book Reviews

UTOPI A, THE MI NI MAL

STATE, AND ENTI TLEMENT

James M. Buchanan-k

Robert Nozick' s important book, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, treats three

major topics that are superficially distinct but closely related at a more

fundamental level of analysis. In their order of presentation, these are (1) the moral

legitimacy of the minimal state and the moral illegitimacy of any other state, (2)

the entitlement theory of distributive justice, and (3) a framework for Utopia. I

shall discuss these topics in the order of the appeal of Nozick' s argument to me,

that is, in the order (3), !1), and (2). His discussion of a utopian framework is

familiar, attractive, and hopefully convincing. Despite the possibility of identifying

important gaps in the analysis, I can accept much of the argument for the minimal

state. But I find Nozick' s entitlement theory of justice t o be unconvincing.

A Libertarian Framework f or Utopia

Economists will recognize Nozick' s framework for Utopia as the world of

competitive clubs (associations), with voluntary entry and exit. The Ti ebout theory

of local government and the related t heory of clubs were initially analyzed in terms

of their efficiency-generating attributes, and most of the subsequent discussion has

been within this setting (see Tiebout, and Buchanan 1965). Dennis Mueller has also

called at t ent i on to the equit T aspects of these models, aspects that economists have

largely neglected. Nozick' s contribution here lies in shifting the analysis of

competitive clubs to the most fundamental realm of discourse, the comparative

evaluation of idealized social orders.

*This is a review article of Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (New York: Basic

Books, 1974). I am indebted to my colleagues, Nicolaus Tideman, Gordon Tullock, and

Richard Wagner for helpful comments.

122 PUBLIC CHOICE

Nozick asks the reader t o dream for himself an ideal world, constrained only

by the recognition that other men, real and imagined, can dream their own worlds.

This rules out the self-interested temptation to invent a Utopia where others bend

to the dreamer' s will. In this conceptual setting, Nozick describes a world in which

each person holds membership in that club which most satisfies his desires, securing

a net value from his membership that is at least equal t o the value of his

contribution to ot her members. Nozick does not, and should not, lay down

constraints on the limits of club action, and his model allows for widely divergent

ranges of activities. So long as persons may voluntarily emigrate and form new clubs

or, i f permitted, j oi n other existing clubs, there are no moral arguments against the

particular activities of any group. In this analysis, and particularly as he moves from

the idealized to the real world, Nozick does not fully consider problems raised by

the definition of rights of members, by the possible absence of effective

entrepreneurship, by the presence of scale economies or diseconomies including

threshold limits and transactions costs, by the potential for interpersonal

discrimination. He acknowledges the incompleteness of his model, however, and his

discussion lends itself admirably to elaboration and extension by more specialized

scholars.

The Minimal State

These clubs are not "states," in Nozick' s usage, and they are, along with their

individual members, presumably subject to the constraints of the minimal state

which is exhaustively discussed earlier in the book. Nozick' s initial objective is the

refutation of the anarchists' claim that any state is immoral. He tries to show that

an entity with the required properties of a state will emerge spontaneously from a

sequence of morally acceptable actions by persons. Nozick places emphasis on this

invisible-hand explanation of the state, and he specifically introduces the analogue

t o the spontaneous coordination of the market.

The starting point is Locke' s state of nature, in which each person has certain

natural rights (more on this below). Anarchy cannot prevail because each person

will recognize that some will t ry to violate the rights of others. Enforcement and

punishment will be necessary, and specialists in these tasks will emerge. Individuals

will purchase the services of protective associations, and, in the ordinary course of

things, one association will come t o a dominant, but not exclusive, position in the

community. To this point, there is no problem. Nozick' s conjectural history is

essentially a positive model of rational individual behavior. The next critical step,

however, is the derivation of exclusivity for one protective association, even in the

absence of voluntary purchase of its services by all persons in the community. To

take this step, Nozick switches to an explicitly normative model and invokes

criteria of morality to evaluate behavior. Through a very complex argument which

involves the risks associated with allowing independents to punish clients of the

protective agency, risks to all clients and not only t o those who are guilty, Nozick

justifies the prohibition oF independents' rights to punish on allegedly moral

grounds. But, this prohibition, in itself, would violate the natural rights of the

REVIEW 12 3

independents; hence they must be compensated which may, in turn, require that

the agency tax its own clients. The compensation will normally take the form of

offers to provide the protective services o the agency to nonclients at below-cost

p r i c e s .

The last part of the argument is not congenial to the public-choice economist,

who is not likely to be primarily interested in morality, which must be recognized

as Nozick' s principal domain. The discussion does expose the contractarian

presuppositions of the whole public-choice framework. In the latter, the legitimacy

of collective action is derived from voluntary agreement, from contract among

individuals with defined rights. The institution of free and voluntary exchange is

generalized to suggest contractual origins of collective action. And even i f this

aspect is not emphasized, "moral legitimacy" is thereby accorded to those activities

of collectivities that embody observed agreement on the part of all persons in the

membership.

Mt hough he does not discuss the point explicitly, Nozick presumably rejects

contractarian explanations of the state on the grounds that these become apologies

for coercion. And, to Nozick, coercion is the primary attribute of the state. The

contractarian is on admittedly weak ground when he uses his criteria to evaluate

existing institutions, which demonstrably embody coercion, on the "as i f"

presumption of contractual origins. This is notably the case when the argument is

not informed by a categorical distinction between ,the constitutional and the

postconstitutional stages o agreement, a distinction that I have repeatedly urged on

fellow social philosophers. Nozick does not seem cognizant of this distinction,

especially when he discusses RaMs' possible response to criticisms of the directly

redistributive measures dictated by Rawlsian precepts of justice. RaMs' possible

argument to the effect that these precepts are designed to be applicable at the

macro level of structure and, therefore, that micro level objections are unfounded,

is held to be invalid by Nozick. While the Rawlsian macro-micro terminology is

highly misleading, there is no inconsistency when the distinction is understood in

the constitutional-postconstitutional context. Contractual agreement may be

reached on rules that operate in subsequent periods so as to embody apparent

coercion.

The Entitlement Theory of Justice

In Part II of the book, Nozick is concerned with defense of the minimal state

against all arguments for extension, holding that all extensions violate the natural

rights of persons. His analysis is, however, devoted almost exclusively to the state' s

possible role in redistribution, which is, of course, the most difficult of all

extensions t o defend. Nozick simply leaves out of account the provision of public

goods (Musgrave's allocation branch), the "economic theory of the state," which

may be contractually derived. He does so, presumably, on the anticontractarian

grounds not ed above, although the possible benefits to be realized from j oi nt or

cooperative ventures t end to be neglected throughout the analysis.

Nozick presents an entitlement t heory of distributive justice, which states

that any distribution of holdings is just i f it has been acquired justly. The process of

124 PUBLIC CHOICE

acquisition and transfer of holdings becomes the central focus of at t ent i on and not

the particular characteristics of any distribution. I share Nozick' s criticism of what

he calls "time-slice" principles of justice, principles whose criteria are drawn from

end results independently of process. On the other hand, Nozick' s own principle of

entitlement seems to me to be open to comparable criticism because it, t oo, looks

at an existent distribution and then applies historical criteria to determine its moral

acceptability. But why is a young Kennedy or Rockefeller "ent i t l ed" to an

inheritance merely because it was voluntarily bequeat hed t o him? 1 What "nat ural

t i ght " is t aken from him when such transfers are limited? And why does it mat t er

at all whether the propert y so bequeat hed was acquired j ust l y or unjustly? As

Bernard Williams not ed in his earlier review (Times Literary Supplement, 17

January t 975), Nozick' s moral evaluation of process would suggest t hat most of

America properly belongs to the Indians (perhaps Marlon Brando has something

after all).

This sort of question exposes the weak link in Nozick' s whole logical

structure, his defense of the starting point in Locke' s state of nature, where persons

are defined with claims to certain ' "natural rights," bot h with respect to physical

objects and to ot her persons. Nozick' s efforts in this respect are no more successful

t han those of Murray Rot hbard and Dax4d Friedman.

Why must a starting poi nt be defined at all? One ultimate purpose may be

of locating some basis for evaluating the social order t hat we observe. In a very real

sense, the starting poi nt is always the status quo, and proposals for i mprovement

must be i nformed by this existential reality. Conceptual origins are helpful,

however, to the ext ent t hat they aid in the evaluation. It will be useful to outline

three recent usages of conceptual origins of social order. These are (1) Nozick' s

state of nature defined in Lockean terms where each person has certain natural

rights, (2) the "original posi t i on" posited by J ohn RaMs, in which persons put on

the "veil of ignorance." and (3) the natural equilibrium in Hobbesian anarchy,

which I have used as a basis for analysis (Buchanan, 1975).

t f distributive justice is to be applied to possible imputations of holdings only

in terms of the process through which these imputations have been created or have

evolved, and i f the moral acceptability of this process is the ultimate test, it

becomes essential t hat some morally justifiable starting point be described. This is

Nozick' s schemata, with Locke' s state of nature in which persons possess natural

@t s assuming the central role.

If, by contrast, criteria for the justice or injustice of social arrangements are

derived from the contractual process through .which these arrangements have been

chosen, or might have been chosen, the origin must be defined in such a way as to

make general agreement possible. I f agreement is to emerge from self-interest,

individuals' roles cannot be identifiable. (We agree on "fai r" rules for a game only

in *he setting in which our own positions are uncertain.) This is the purpose of

1This is admittedly an extreme example with perhaps unfair emotional overstones.

Nozick's argument becomes much more pesuasive if it could, somehow, be limited to apply to

the distribution of earnings based on relative e/tort. But it is precisely the extreme examples

that make the moral acceptance of the entitlement theory so difficult.

REVIEW 125

RaMs' original position. Although ambiguities in RaMs' presentation must be

acknowledged, Nozick' s criticism of the Rawlsian principles on the grounds that

these are derived from end-result norms seems to me to be misplaced.

(Unfortunately, many of the interpretations of RaMs' principles do treat these

strictly as end-result norms.)

Finally, i f the purpose is not that of making moral judgments about the

existing social order, but instead is that of seeking the basis for

mutually-advantageous changes in the socio-tegat-political structure of society, it is

helpful to think of conceptual origins in which men are observed to be unequal in

the distribution of endowments. In this context. I have found the natural

equilibrium in a Hobbesian rather than a Lockean state of nature to offer

productive insights. In the former, rights are not defined, and individuals may differ

in strengths and abilities. The protective state that emerges from the basic

constitutional contract in this setting need not itself by Hobbesian. In my

derivation, this state is similar to the minimal state described by Nozick. In my

analysis, however, all persons are brought into the protective umbrella, are brought

under law and are subjected to punishment on violation of law, because they retain

n o rights by remaining outside the contract. My contractarian model does not,

however, allow the state to be closed of f at these limits. I f contractual agreements

emerge for the provision of jointly-consumed public goods, there may be a role for

a productive as well as for a protective state. These need not, however, have

common boundaries, and the desired provision of public goods may be organized

through clubs or associations (local governmental units) among which migration is

possible. Aside from utility interdependence, however, direct redistributive action is

not conceptually possible within the strict contractarian framework i f at t ent i on is

confined to the post-constitutional level. However, at the constitutional stage,

where individual income and wealth positions are not known, structural

arrangements may be agreed upon that will allow for apparent redistribution at the

postconstitutional stage (Buchanan and Tullock). In this respect, my own

derivation can be made consistent with the RaMsian process, although not wi t h

particular principles.

Nozick' s wholly different approach forces me to acknowledge the basic

weakness in the constractarian approach, not ed above. There is a fundamental

difference between those institutions embodying apparent coercion that may be

conceptually legitimatized as having emerged from contractual agreement and those

institutions, again embodying apparent coercion, that have been observed to emerge

from actual agreement. And, of course, the latter are rare indeed. Nonetheless, I

should still argue that the contractarian approach does generate criteria that

disqualify certain intrusions on individual liberty. "Could we have reached

agreement?" seems to me t o be a more appealing intellectual question and a more

discriminating instrument for evaluation than "did this violate someone' s natural

rights?" And surely "can we reach agreement?" offers a more satisfactory propect

for achieving meaningful change than "what do we have the right t o do?"

Agreement is operationally testable; men fight over disputes about rights.

126 PUBLIC CHOICE

To establish morally legitimate claims to rights, Nozick would have us l ook at

the process of acquisition. In a world where the minimal state exists, and where its

own limits are widely accepted, this might be a meaningful approach. But why

should agreement emerge when the claims that seem justified by Nozick' s process

conflict with individual rights that seem to be embodied in the democratic franchise

of the supraminimal state? How can Nozick expect his argument for the minimal

state t o be convincing until and unless he first unravels, also through agreement, the

maze of conflicting "public entitlements" that membership in the modern state

seems to carry with it?

The multiplicity of conflicting claims should not be overemphasized. Within

limits, the social process remains orderly, and thereby reasonably productive. Had

Nozick grounded his entitlement theory of.rights, not on norms of justice but on

those of productive social order, his whole analysis would have been more readily

acceptable. I f men can agree on rights, the problem of social order is largely

resolved. I am not convinced that Nozick's argument does much toward securing

such agreement. And i f I, who share so many of Nozick' s libertarian

presuppositions, am not persuaded, how can he expect to fare with his peers in the

Cambridge (Massachusetts) intellectual establishment?

REFERENCES

Buchanan, James M. "An Economic Theory of Clubs." Economica, 32 (February

1965), 1-14.

, and Tullock, Gordon. The Calculus of Consent. Ann Arbor: University of

Michigan Press, 1962.

, The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathan. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Friedman, David. The Machinery of Freedom. New York: Harper, 1973.

Nozick, Robert. Anarchy, State and Utopia. New York: Basic Books, 1974.

MueUer, Dennis. "Achieving the Just Pol i t y. " American Economic Review, 64 (May

1974), 147-152.

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971.

Rothbard, Murray. For a New Liberty. New York: Macmi/lan, 1974.

Tiebout, C. M. "A Pure Theory of Local Government Expenditure. " Journal of

Political Economy, 64 (October 1956), 416-424.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Water Law OutlineDocument65 pagesWater Law OutlinejmccloskPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Gear Krieg - Axis Sourcebook PDFDocument130 pagesGear Krieg - Axis Sourcebook PDFJason-Lloyd Trader100% (1)

- Case 104-Globe Mackay Cable and Radio Corp V NLRCDocument1 pageCase 104-Globe Mackay Cable and Radio Corp V NLRCDrobert EirvenPas encore d'évaluation

- Immanuel Wallerstein Precipitate DeclineDocument6 pagesImmanuel Wallerstein Precipitate DeclineGeriPas encore d'évaluation

- Imbong Vs OchoaDocument2 pagesImbong Vs OchoaReyn Arcenal100% (1)

- Privacy-Enhancing Technologies: 1. The Concept of PrivacyDocument18 pagesPrivacy-Enhancing Technologies: 1. The Concept of PrivacyarfriandiPas encore d'évaluation

- Inventing Eastern Europe The Map of Civili - Larry WolffDocument436 pagesInventing Eastern Europe The Map of Civili - Larry WolffGiorgos KyprianidisPas encore d'évaluation

- Command History 1964Document209 pagesCommand History 1964Robert Vale100% (1)

- Human Rights: Global Politics Unit 2Document28 pagesHuman Rights: Global Politics Unit 2Pau GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- CITES Customs Procedure GuideDocument1 pageCITES Customs Procedure GuideShahnaz NawazPas encore d'évaluation

- X. Property Relations - Salas, Jr. Vs AguilaDocument2 pagesX. Property Relations - Salas, Jr. Vs AguilaSyElfredG100% (1)

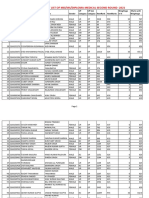

- UP MDMS Merit List 2021 Round2Document168 pagesUP MDMS Merit List 2021 Round2AarshPas encore d'évaluation

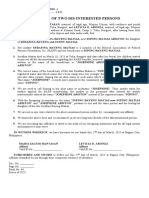

- Criminal Complaint - Stephanie BaezDocument14 pagesCriminal Complaint - Stephanie BaezMegan ReynaPas encore d'évaluation

- Josephine Matias Ariston-BARPDocument1 pageJosephine Matias Ariston-BARPJules DerickPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis and Summary. SPAIN UNIQUE HISTORYDocument4 pagesAnalysis and Summary. SPAIN UNIQUE HISTORYLYDIA HERRERAPas encore d'évaluation

- The Comparison Between Clausewitz and Sun Tzu in The Theorytical of WarDocument8 pagesThe Comparison Between Clausewitz and Sun Tzu in The Theorytical of WarMuhd Ariffin NordinPas encore d'évaluation

- General Knowledge: Class Code - 007Document5 pagesGeneral Knowledge: Class Code - 007Suresh KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Norms Standards Municipal Basic Services in India NIUADocument41 pagesNorms Standards Municipal Basic Services in India NIUASivaRamanPas encore d'évaluation

- So, Too, Neither, EitherDocument13 pagesSo, Too, Neither, EitherAlexander Lace TelloPas encore d'évaluation

- The Tradition of Baralek Gadang (Big Party) Weddings in Minangkabau SocietyDocument3 pagesThe Tradition of Baralek Gadang (Big Party) Weddings in Minangkabau SocietySaskia Putri NabillaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Trial and Execution of BhuttoDocument177 pagesThe Trial and Execution of BhuttoSani Panhwar67% (3)

- Letter From ED To Corps Reg SBM2.0 Guidelines 26.10.2021 - FinalDocument3 pagesLetter From ED To Corps Reg SBM2.0 Guidelines 26.10.2021 - FinalEr Pawan JadhaoPas encore d'évaluation

- 201232630Document40 pages201232630The Myanmar TimesPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 1 Administrative System at The Advent of British RuleDocument11 pagesUnit 1 Administrative System at The Advent of British RuleneelneelneelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Politics NOTESDocument6 pagesPhilippine Politics NOTESMERBUEN BACUSPas encore d'évaluation

- Fiqh 2 - Kitab Al-HajjDocument7 pagesFiqh 2 - Kitab Al-HajjNoor-uz-Zamaan AcademyPas encore d'évaluation

- Independence and Partition (1935-1947)Document3 pagesIndependence and Partition (1935-1947)puneya sachdevaPas encore d'évaluation

- EIIB Employees Challenge Deactivation OrderDocument7 pagesEIIB Employees Challenge Deactivation OrderjannahPas encore d'évaluation

- Ch08 - Water SupplyDocument20 pagesCh08 - Water SupplyRudra Pratap SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Aunt Bessie EssayDocument2 pagesAunt Bessie Essayapi-250139208Pas encore d'évaluation