Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding PDF

Transféré par

Anonymous pJfAvlTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding PDF

Transféré par

Anonymous pJfAvlDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

www.medscape.

com

From Journal of Pediatric Health Care

Introduction

Abnormal vaginal bleeding is a common cause for concern among adolescents and their families, as well as a frequent

cause of visits to the emergency department and health care provider. While there are many causes of abnormal vaginal

bleeding, the most likely cause among otherwise healthy adolescents is dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) resulting

from an immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, which results in anovulatory cycles and unpredictable bleeding.

However, abnormal vaginal bleeding also may be the presenting symptom of a more serious underlying condition or

problem. Furthermore, depending on the cause and severity of the bleeding, significant morbidity and mortality may be

associated with it. This article will discuss many of the common causes of DUB, as well as the diagnostic work-up and

management for this condition.

Definitions

Normal Bleeding

For most girls, menarche usually occurs within 2 to 3 years after the appearance of breast buds (Carswell &

Stafford, 2008).

The mean age of menarche varies somewhat based on ethnicity: 12.7 years for non-Hispanic White girls, 12.3

years for Black girls, and 12.5 years for Mexican American girls (Wu, Mendola, & Buck, 2002).

Many teens then experience "irregular" periods for 2 to 3 years following menarche because of anovulatory cycles

and an immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (Gray and Emans, 2007, Lavin, 1996).

Once "regular" menses are established, normal menstrual cycles are 21 to 40 days long, with bleeding usually

lasting 2 to 7 days and an average blood loss of 20 to 80 mL (Mitan & Slap, 2008).

Abnormal Bleeding

Menorrhagia is bleeding that lasts more than 7 consecutive days or is more than 80 mL of blood loss but still

occurs at regular intervals.

Bleeding that occurs at irregular intervals is termed metrorrhagia, and heavy irregular bleeding is

menometrorrhagia.

If menstrual cycles occur at intervals from 41 days to 3 months apart, this is considered to be oligomenorrhea.

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is defined as abnormal shedding of the uterine lining in the absence of a structural

or medical abnormality and is most often due to anovulation (Gray and Emans, 2007, Mitan and Slap, 2008).

Although underlying pathology accounts for less than 10% of abnormal bleeding (Mitan & Slap, 2008), DUB is a

diagnosis of exclusion, and other causes must be ruled out.

Key to diagnosing the etiology of abnormal menstrual bleeding is a good history of the patient's cycles, including an

assessment of the amount of flow, to determine if her experiences are truly outside the realm of normal.

Differential Diagnosis

Of the many causes of abnormal bleeding ( Box ), some causes require immediate exclusion because failure to do so

may result in significant morbidity and mortality.

Authors and Disclosures

Laura J. Benjamins, MD, MPH, Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, The University of Texas Medical School

at Houston, Houston, TX.

Laura J. Benjamins, MD, MPH

Posted: 07/13/2009; J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23(3):189-193. 2009 Mosby, Inc.

Box. Differential Diagnosis For Abnormal Bleeding in Adolescents

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding in Adolesce... http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704152_print

1 of 7 30/07/2010 9:25

Pregnancy

Implantation

Ectopic pregnancy

Threatened, spontaneous, or missed abortion

Retained products of conception

Placenta accreta

Hematologic

Thrombocytopenia

von Willebrand disease

Factor deficiencies

Coagulation defects

Platelet dysfunction

Endocrine

Thyroid disorders

Hyperprolactinemia

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

Adrenal disorders

Ovarian failure

Infectious

Cervicitis (especially chlamydia)

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Pathology of the Reproductive Tract

Polyp

Fibroid

Myoma

Cervical dysplasia

Endometriosis

Medication

Hormonal contraceptives

Antipsychotics

Platelet inhibitors

Anticoagulants

Trauma

Sexual abuse

Laceration

Foreign body

Related to abortion or other surgical procedure

Other

Stress

Excessive exercise

Eating disorders

Systemic disease

Intrauterine device

Data from Emans, S. J., 2005.

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding in Adolesce... http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704152_print

2 of 7 30/07/2010 9:25

Pregnancy-related complications can present with any pattern of abnormal bleeding, with ectopic pregnancy being

one of the more serious conditions to consider.

Severe thrombocytopenia can be assessed quickly with a complete blood cell count.

A teen is more likely to have an underlying abnormality if she has to be hospitalized and her hemoglobin is less than

10 g/dL (Claessens & Cowell, 1981).

Pelvic inflammatory disease may present with vaginal bleeding in addition to lower abdominal pain.

While adult women frequently have underlying pathology such as fibroids, dysplasia, or cancer, teens rarely

present with such conditions. However, these conditions are sometimes seen in young women, and they must

remain in the differential of abnormal bleeding (Emans, 2005).

History

Medical and Surgical History

Systemic disease

Anemia

History of abortion and/or dilation and curettage

Current and recent medications: prescribed, over the counter, herbal

Prior chemoth6erapy

Menstrual History

Age at menarche

-The patient who is older at menarche is more likely to have a longer time of anovulatory, "irregular" cycles (Vihko &

Apter, 1984)

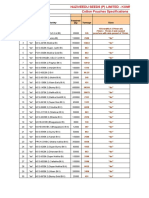

Length of cycles as determined by recording data on a calendar (Figure)

Length of bleeding in days as determined by recording data on a calendar

The number, if any, of "regular" periods experienced by the patient

Number of pads or tampons used in a 24-hour period and for how many days

-More than three soaked pads or six full regular-absorbency tampons a day for 3 or more days likely equates to

greater than 80 mL of blood loss (Brown, 2005)

History of flooding, clots or leaking, especially overnight, because this may be associated with a clotting disorder

(Brown, 2005)

Characteristics of the patient's very first period

-A "heavy" first period may be indicative of a bleeding diathesis, most commonly von Willebrand disease

(Claessens and Cowell, 1981, Brown, 2005)

Figure. Menstrual Calendar

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding in Adolesce... http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704152_print

3 of 7 30/07/2010 9:25

Social and Sexual History

Risk factors for sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy:

-Age of sexual debut and number of lifetime partners

-Date of last sexual activity and use of protection or not (condoms)

-History of a sexually transmitted infection in patient and partner(s)

-Sexual abuse (may also be associated with trauma)

Bleeding abnormalities may be associated with eating disorders and/or extreme physical activity; therefore, one

should ask about:

-Diet

-Exercise

Stress is associated with anovulation and DUB; therefore, one should inquire about:

-Illicit drug use

-Psychosocial stressors

Family History

Other female relatives with heavy periods or history of hysterectomy after childbirth because of bleeding (common

for von Willebrand disease)

Other family members with clotting problems, such as after circumcision, dental extraction, or a surgical procedure

Autoimmune diseases

Endocrine disorders

Cancer

Review of Systems

In addition to the pattern of bleeding and the amount of flow, other complaints found on the review of symptoms may

identify an underlying etiology (Table).

General: Fatigue; change in weight; night sweats, or hot flashes

Head, eyes, ears, nose, throat: Gum or nose bleeding

Cardiovascular: Palpitations; tachycardia

Respiratory: Shortness of breath

Gastrointestinal: Diarrhea; constipation

Genitourinary: Dysuria; vaginal discharge; dyspareunia; dysmenorrhea

Hematologic: Easy bleeding or bruising

Neurologic: Headaches; double vision or loss of vision

Table. Review of Systems and Physical Examination Findings and Possible Differential Diagnoses

Review of systems Physical examination Differential diagnoses

Heavy periods since menarche

Signs and symptoms of anemia

tachycardia, flow murmur, pallor

Bleeding disorder; most likely von

Willebrand

Easy bruising, gum bleeding, nose

bleeds

Bruises, petechiae

Platelet dysfunction;

thrombocytopenia

Heat/cold intolerance, weight

changes, diarrhea or constipation

Goiter, brittle hair, and nails Thyroid disorders

Nipple discharge

Galactorrhea, possible peripheral visual

field deficits

Prolactinemia; prolactinoma;

antipsychotic agents

Abnormal hair growth Facial hair, acne Polycystic ovarian syndrome

Dysuria, discharge

Vaginal discharge, inflamed vagina or

cervix

Vaginitis; cervicitis

Abdominal pain

Cervical motion, adnexal or uterine

tenderness

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding in Adolesce... http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704152_print

4 of 7 30/07/2010 9:25

Skin: Abnormal hair growth; acne; hair loss

Other: Nipple discharge

Physical Examination

In a patient with prolonged or heavy bleeding, an evaluation should al ways begin with vital signs. Attention is focused on

signs of anemia, as well as clues of other possible underlying causes ( Table ).

Vital signs: Is the patient hemodynamically stable, tachycardic, or hypotensive? Are there orthostatic changes?

General: Is the patient pale, or does she appear tired? Is there altered mental status? Is there obesity, or is the

patient excessively thin?

Head, eyes, ears, nose, throat: Is there conjunctival pallor, epistaxis, or gum bleeding?

Neck: Are lymphadenopathy or thyromegaly noted?

Breast: Is galactorrhea noted? If so, nipple discharge should be evaluated microscopically for fat globules.

Heart: Is a flow murmur present?

Abdomen: Are hepatosplenomegaly or lower abdominal pain identified?

Genitourinary: On external examination, are discharge, inflammation, lacerations, or other signs of trauma found? Is

the clitoris of normal size? Is the bleeding in fact from the vagina? Is a foreign body (e.g., a retained tampon)

present? Is the cervix normal, and does movement of it or the adnexa or uterus result in pain?

-For patients who cannot tolerate a speculum or bimanual examination, a pelvic examination may need to be done

under anesthesia.

Skin: Are findings of bruises, petechiae, acne, hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans, or striae noted?

Neurologic: Are visual field deficits noted?

Laboratory and Other Studies

Initial work-up should include the following:

Urine pregnancy test and/or quantitative serum pregnancy test

Complete blood cell count with differential and platelet count

A pelvic ultrasound also may aid in the diagnosis

If bleeding is severe or an underlying bleeding disorder is suspected because of the history of physical examination, the

following can be ordered (Brown, 2005):

Prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time

Bleeding time and platelet aggregation

Table. Review of Systems and Physical Examination Findings and Possible Differential Diagnoses

Review of systems Physical examination Differential diagnoses

Heavy periods since menarche

Signs and symptoms of anemia

tachycardia, flow murmur, pallor

Bleeding disorder; most likely von

Willebrand

Easy bruising, gum bleeding, nose

bleeds

Bruises, petechiae

Platelet dysfunction;

thrombocytopenia

Heat/cold intolerance, weight

changes, diarrhea or constipation

Goiter, brittle hair, and nails Thyroid disorders

Nipple discharge

Galactorrhea, possible peripheral visual

field deficits

Prolactinemia; prolactinoma;

antipsychotic agents

Abnormal hair growth Facial hair, acne Polycystic ovarian syndrome

Dysuria, discharge

Vaginal discharge, inflamed vagina or

cervix

Vaginitis; cervicitis

Abdominal pain

Cervical motion, adnexal or uterine

tenderness

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding in Adolesce... http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704152_print

5 of 7 30/07/2010 9:25

von Willebrand panel (done prior to initiating hormonal therapy)

Factor levels and activity (depending on family history and ethnicity)

If an endocrine disorder is suspected:

Thyroid-stimulating hormone to screen for thyroid disorders

Prolactin (can be mildly elevated after a breast examination; levels >100 ng/mL suggest a pituitary adenoma)

Total and free testosterone (usually elevated in polycystic ovarian syndrome)

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate to assess for adrenal tumors

Luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone (may aid in the evaluation of pituitary or ovarian function)

For patients with suspected infectious etiologies:

Wet mount of discharge if bleeding not severe

Urine nucleic amplification test for gonorrhea and chlamydia

Management

The management of abnormal vaginal bleeding is determined by the underlying etiology and by the severity of the

bleeding. The goals of controlling abnormal bleeding include preventing complications, such as anemia, as well as

restoring regular cyclical bleeding. Underlying systemic, endocrine disorders or bleeding disorders are addressed, and

patients may require referral to appropriate specialists for further evaluation and management if one of these conditions is

identified. Guidelines for management of abnormal bleeding related to hormonal contraception, bleeding diatheses, and

polycystic ovarian syndrome can be found elsewhere (see Brown, 2005, Emans, 2005, Mitan and Slap, 2008, Speroff and

Fritz, 2005).

For the patient in whom no other etiology is found, management of DUB will in part be directed by the amount of flow, the

degree of associated anemia, and patient and family comfort with different treatment modalities (Gray and Emans, 2007,

Mitan and Slap, 2008, Speroff and Fritz, 2005).

Light to Moderate Flow; Hemoglobin >12 g/dL

Reassurance

Multivitamin with iron

A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug may help to decrease flow

Re-evaluate patient in 3 months; sooner if bleeding persists or becomes more severe

Moderate Flow; Hemoglobin 10 to 12 g/dL

Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) (e.g., monophasic with 30 to 35 g of ethinyl estradiol)

-One pill twice daily for 1 to 5 days, until the bleeding stops

Once the bleeding stops, continue OCPs with a new pack, one pill daily, for 3 to 6 months

Iron supplementation (e.g., ferrous sulfate 325 mg twice daily) for 6 months to replenish iron stores

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be helpful

Heavy Flow; Hemoglobin 8 to 10 g/dL; Hemodynamically Stable

May be able to manage the patient as under "Moderate Flow" if the family can assist with the management plan and

follow-up

If bleeding persists, increase the OCP to 3 or 4 times a day for a few days until the bleeding slows, then taper to

two then one pill daily; patient may require an antiemetic prior to each pill to help prevent nausea

Follow closely; once bleeding stops, continue daily pills for 6 months

Heavy Flow; Hemoglobin <7 g/dL or if Hemodynamically Unstable

Admit to the hospital

Consider blood transfusion depending on degree and persistence of bleeding, as well as severity of hemodynamic

instability

Begin OCP with 50 g of ethinyl estradiol every 6 hours until bleeding slows

Taper administration of pills to one pill a day over the next 7 days (e.g., one pill every 6 hours for 2 days, then every

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding in Adolesce... http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704152_print

6 of 7 30/07/2010 9:25

8 hours for 2 days, every 12 hours for 2 days, then once daily)

Anti-emetic agents likely will be needed

If bleeding does not slow after the first two doses of the 50 g OCP, conjugated estrogens given intramuscularly or

intravenously at a dose of 25 mg every 6 hours to a maximum 6 doses may be initiated

If bleeding still persists, consider dilation and curettage

For patients with a contraindication to estrogen-containing regimens, progesterone, 10 mg once daily for 5 to 10 days,

may be effective for light to moderate flow. Patients also may be cycled monthly on a progesterone-only regimen. Other

alternatives include depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, 150 mg intramuscularly every 3 months, or a levonorgestrel

intrauterine device (which lasts for 5 years). These latter methods, however, often are associated with irregular bleeding

and spotting themselves.

Summary

Abnormal vaginal bleeding in adolescents is a common occurrence, and the primary care provider should be comfortable

with its evaluation and management. While most adolescents will require only outpatient management and reassurance as

their cycles become ovulatory over time, health care providers must evaluate each teen closely so that significant

pathology can be quickly identified and treated appropriately.

Correspondence: Laura J. Benjamins, MD, MPH, University of Texas Medical School at Houston, 1133 John Freeman Blvd, JJL 495, Houston, TX

70030; E-mail: laura.j.benjamins@uth.tmc.edu

J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23(3):189-193. 2009 Mosby, Inc.

References

Brown, D. L. (2005). Congenital bleeding disorders. Current Problems in Pediatric & Adolescent Health Care, 35,

38-62.

Carswell, J. M., & Stafford, D. E. J. (2008). Normal physical growth and development. In L. S. Neinstein, C. N.

Gordon, D. K. Katzman, D. S. Rosen, & E. R. Woods (Eds.), Adolescent health care: A practical guide (5th ed.)

(pp. 3-26) Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Claessens, E. A., & Cowell, C. A. (1981). Dysfunctional uterine bleeding in the adolescent. Pediatric Clinics of

North America, 28, 369-378.

Emans, S. J. (2005). Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. In S. J. Emans, M. R. Laufer, & D. P. Goldstein (Eds.),

Pediatric and adolescent gynecology (5th ed., pp. 270286). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Gray, S. H., & Emans, S. J. (2007). Abnormal vaginal bleeding in adolescents. Pediatrics in Review, 28, 175-182.

Lavin, C. (1996). Dysfunctional uterine bleeding in adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 8, 328-332.

Mitan, L. A. P., & Slap, G. B. (2008). Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. In L. S. Neinstein, C. N. Gordon, D. K.

Katzman, D. S. Rosen, & E. R. Woods (Eds.), Adolescent health care:Apractical guide (5th ed.) (pp. 687-690).

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Speroff, L., & Fritz, M. A. (2005). Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility

(7th ed., pp. 547571). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Vihko, R., & Apter, D. (1984). Endocrine characteristics of adolescent menstrual cycles: Impact of early menarche.

Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 20, 231-236.

Wu, T., Mendola, P., & Buck, G. M. (2002). Ethnic differences in the presence of secondary sex characteristics and

menarche among US girls: The third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-1994. Pediatrics, 110,

752-757.

Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding in Adolesce... http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704152_print

7 of 7 30/07/2010 9:25

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- D. Michael Quinn-Same-Sex Dynamics Among Nineteenth-Century Americans - A MORMON EXAMPLE-University of Illinois Press (2001)Document500 pagesD. Michael Quinn-Same-Sex Dynamics Among Nineteenth-Century Americans - A MORMON EXAMPLE-University of Illinois Press (2001)xavirreta100% (3)

- Analysis of The Tata Consultancy ServiceDocument20 pagesAnalysis of The Tata Consultancy ServiceamalremeshPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 CAAT-AIR-GM03 Guidance-Material-for-Foreign-Approved-Maintenance-Organization - I3R0 - 30oct2019 PDFDocument59 pages7 CAAT-AIR-GM03 Guidance-Material-for-Foreign-Approved-Maintenance-Organization - I3R0 - 30oct2019 PDFJindarat KasemsooksakulPas encore d'évaluation

- IsaiahDocument7 pagesIsaiahJett Rovee Navarro100% (1)

- 2nd Quarter Exam All Source g12Document314 pages2nd Quarter Exam All Source g12Bobo Ka100% (1)

- Value Chain AnalaysisDocument100 pagesValue Chain AnalaysisDaguale Melaku AyelePas encore d'évaluation

- Task Performance Valeros Roeul GDocument6 pagesTask Performance Valeros Roeul GAnthony Gili100% (3)

- 06 Ankit Jain - Current Scenario of Venture CapitalDocument38 pages06 Ankit Jain - Current Scenario of Venture CapitalSanjay KashyapPas encore d'évaluation

- EScholarship UC Item 8k05n5csDocument10 pagesEScholarship UC Item 8k05n5csAnonymous pJfAvlPas encore d'évaluation

- Left Ovarian Brenner Tumor: Key-Word: Ovary, NeoplasmsDocument2 pagesLeft Ovarian Brenner Tumor: Key-Word: Ovary, NeoplasmsAnonymous pJfAvlPas encore d'évaluation

- Aafp PDFDocument8 pagesAafp PDFAnonymous umFOIQIMBAPas encore d'évaluation

- Executive Summary of Methanol Poisoning - 03Document13 pagesExecutive Summary of Methanol Poisoning - 03Anonymous pJfAvl100% (1)

- Oxygen-Free Radicals Impair Fracture Healing in Rats: A Were ofDocument3 pagesOxygen-Free Radicals Impair Fracture Healing in Rats: A Were ofAnonymous pJfAvlPas encore d'évaluation

- Determination of Physicochemical Pollutants in Wastewater and Some Food Crops Grown Along Kakuri Brewery Wastewater Channels, Kaduna State, NigeriaDocument5 pagesDetermination of Physicochemical Pollutants in Wastewater and Some Food Crops Grown Along Kakuri Brewery Wastewater Channels, Kaduna State, NigeriamiguelPas encore d'évaluation

- Kangaroo High Build Zinc Phosphate PrimerDocument2 pagesKangaroo High Build Zinc Phosphate PrimerChoice OrganoPas encore d'évaluation

- HP MSM775 ZL Controller Installation GuideDocument21 pagesHP MSM775 ZL Controller Installation GuidezarandijaPas encore d'évaluation

- Task 2 - The Nature of Linguistics and LanguageDocument8 pagesTask 2 - The Nature of Linguistics and LanguageValentina Cardenas VilleroPas encore d'évaluation

- Venue:: Alberta Electrical System Alberta Electrical System OperatorDocument48 pagesVenue:: Alberta Electrical System Alberta Electrical System OperatorOmar fethiPas encore d'évaluation

- Solution Document For Link LoadBalancerDocument10 pagesSolution Document For Link LoadBalanceraralPas encore d'évaluation

- RPS Manajemen Keuangan IIDocument2 pagesRPS Manajemen Keuangan IIaulia endiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Budget ProposalDocument1 pageBudget ProposalXean miPas encore d'évaluation

- أثر البحث والتطوير على النمو الاقتصادي - دراسة قياسية لحالة الجزائر (1990 -2014)Document17 pagesأثر البحث والتطوير على النمو الاقتصادي - دراسة قياسية لحالة الجزائر (1990 -2014)Star FleurPas encore d'évaluation

- Mbtruck Accessories BrochureDocument69 pagesMbtruck Accessories BrochureJoel AgbekponouPas encore d'évaluation

- Indiabix PDFDocument273 pagesIndiabix PDFMehedi Hasan ShuvoPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution Epidemiology and Etiology of Temporomandibular Joint DisordersDocument6 pagesEvolution Epidemiology and Etiology of Temporomandibular Joint DisordersCM Panda CedeesPas encore d'évaluation

- For Printing Week 5 PerdevDocument8 pagesFor Printing Week 5 PerdevmariPas encore d'évaluation

- Julian BanzonDocument10 pagesJulian BanzonEhra Madriaga100% (1)

- Agitha Diva Winampi - Childhood MemoriesDocument2 pagesAgitha Diva Winampi - Childhood MemoriesAgitha Diva WinampiPas encore d'évaluation

- Cotton Pouches SpecificationsDocument2 pagesCotton Pouches SpecificationspunnareddytPas encore d'évaluation

- Lyndhurst OPRA Request FormDocument4 pagesLyndhurst OPRA Request FormThe Citizens CampaignPas encore d'évaluation

- Did Angels Have WingsDocument14 pagesDid Angels Have WingsArnaldo Esteves HofileñaPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL Week 7 MathDocument7 pagesDLL Week 7 MathMitchz TrinosPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Networking ProjectDocument11 pagesSocial Networking Projectapi-463256826Pas encore d'évaluation

- Peptic UlcerDocument48 pagesPeptic Ulcerscribd225Pas encore d'évaluation

- Forensic BallisticsDocument23 pagesForensic BallisticsCristiana Jsu DandanPas encore d'évaluation