Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Korean Woman Mammography Screening

Transféré par

Jesse M. MassieDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Korean Woman Mammography Screening

Transféré par

Jesse M. MassieDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Health Care for Women International, 29:151164, 2008

Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0739-9332 print / 1096-4665 online

DOI: 10.1080/07399330701738176

Stages of Change: Korean Womens Attitudes

and Barriers Toward Mammography Screening

HEE SUN KANG

Department of Nursing, College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University, 221 Heuksukdong

Dongjakku, Seoul, Korea

EILEEN THOMAS

University of Colorado, School of Nursing, Denver, Colorado, USA

BO EUN KWON

Seoul Womens College of Nursing, Seoul, Korea

MYUNG-SUN HYUN

College of Nursing, Ajou University, Suwon, Korea

EUN MI JUN

Department of Nursing, College of Medicine, Dongeui University, Busan, Korea

The positive and negative aspects of breast cancer screening were

measured to gain insight into the barriers that prevent Korean

women from participating in mammography screening. Breast

cancer screening behaviors, attitudes, and barriers were identied

from a convenience sample of 328 Korean women recruited in

Seoul, Gyeonggi, and Jeju, South Korea. Pros, cons, and decisional

balance constructs of the transtheoretical model of behavior change

were used to identify stages of change in attitude related to

mammography screening. There were signicant differences inpros

(F = 5.175, p = .001) and cons (F = 3.357, p = .012) across the

ve stages of change for mammography. Participants indicated

that the major barriers to mammography screening were, in order

of frequency, the belief that an absence of symptoms meant there

was no need for a breast examination, the high cost of breast cancer

screening, lack of time, lack of information, embarrassment, fear

about x-rays and test results, reliance on breast self-examination

Received 22 March 2006; accepted 17 August 2007.

Address correspondence to Eileen Thomas, PhD, RN, Assistant Professor, University

of Colorado, School of Nursing, 4200 E 9th Avenue, C288-18, Denver, CO 80262, USA.

E-mail: Eileen.Thomas@uchsc.edu

151

152 H. S. Kang et al.

(BSE), and discomfort or pain. The benets of breast cancer

screening should be emphasized among Korean women.

Previous studies primarily have focused on Korean womens screening

rates and predictive factors of participation in all three measures of

breast cancer screening. Little information is available, however, on Korean

womens attitudes toward and barriers to mammography. The authors used

the transtheoretical model of behavioral change to explore Korean womens

BSE, clinical breast examination (CBE) and mammography screening

behaviors; examined womens attitudes toward various stages of change

related to mammography screening; and identied barriers to mammography

screening. Findings suggest that attitudes toward breast cancer screening

and barriers to mammography screening should be explored further among

Korean women, but these barriers are not unique to a specic geographical

location. We recommend that future research should take a more global and

interdisciplinary approach.

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer in Korean women.

Mortality rates are slowly rising in Korea, and the incidence is expected to

increase over time (Ahn, Yoo, & Korean Breast Cancer Society, 2006; Choi,

Kim, Shin, Noh, & Yoo, 2005). Unlike in the United States and Switzerland,

where the incidence does not peak until women are over the age of 50 years,

incidence rates begin to rise when Korean women are in their early thirties

and peak between the ages of 40 and 50 (Bouchardy et al., 2006; Smigal

et al., 2006).

Breast cancer is dened as a multifactorial disease caused by nongenetic

and genetic factors. Currently, there are no accepted and recognized standard

methods of breast cancer prevention. Although there remains discord

within the healthcare community about appropriate breast cancer screening

measures, currently breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination

(CBE), and mammography offer the greatest hope for reducing mortality and

improving survival (Thomas, 2004, p. 296). For women with an average

risk of getting breast cancer, the American Cancer Society (ACS, 2001)

recommends annual mammography screening beginning at age 40, annual

CBE for women aged 40 and older, and CBE every 3 years for women

between the ages of 20 and 40 (Smith et al., 2003). The Korean Breast

Cancer Society and the Korean National Cancer Center recommend monthly

BSE for women aged 30 and older, CBE every 2 years for women aged 35

and older, and regular mammography screening and CBE at least once every

1 to 2 years for women aged 40 and older (National Cancer Center, 2006).

However, a national survey showed that Korean womens breast cancer

screening rates remain at a low level of 13.3% (Sung, Park, Shin, & Choi,

2005).

Korean Womens Attitudes Toward Mammography 153

BACKGROUND

The transtheoretical model of behavioral change has been used to assess

womens breast cancer screening behaviors and to promote breast cancer

screening (Tu et al., 2002). Developed in 1979, the transtheoretical model is

the result of a comparative analysis of 18 major theories of psychotherapy

and behavioral change and is used to conceptualize the process of intentional

behavior change. According to this model, behavior change is viewed as a

ve-stage process or continuum related to a persons readiness to change.

The ve stages are precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action,

and maintenance. Each stage is characterized by changes in decisional

balance, or the balance between benets and costs associated with engaging

in a particular behavior (Prochaska, Norcross, & DiClemente, 1994).

Findings from previous studies in diverse age groups and ethnic popula-

tions indicated that the decisional balance between pros and cons regarding

mammography was associated with mammography stage in Filipino, Latino,

African American, Chinese, and White women (Otero-Sabogal, Stewart,

Shema, & Pasick, 2006). However, more research is being recommended:

with more diverse populations (Spencer, Pagell, & Adams, 2005). In addition,

there are inconsistent results on the crossover between the pros and cons of

mammography screening that occurred in the contemplation stage (Chamot,

Charvet, & Perneger, 2001) or in closer to the action stage (Prochaska,

Velicer, et al., 1994). There is also a paucity of research on the decisional

balance and stage of change of mammography among Korean women,

although health care providers must gain a better understanding of the

decisional balance and subsequent stages of change to develop the most

effective screening promotion strategies. Also, efforts to explore barriers

to mammography that have not been examined in previous studies may

increase early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among Korean

women. Overall, this study will help bridge the gap in existing knowledge.

METHODS

Setting and Sample

A cross-sectional, descriptive study design was used for this study. A

convenience sample of 328 women aged 30 years and older with no

history of breast cancer was recruited from three urban areas in South

Korea: Seoul, Gyeonggi, and Jeju. Data were collected over a 4-month

period, from June 1 through September 30, 2004, using self-administered

questionnaires. The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee

of the National Health Insurance Corporation Ilsan Hospital, and all

participants provided informed consent prior to completing the survey. To

154 H. S. Kang et al.

increase the representative nature of our study, we included unemployed

and employed women. All participants were informed about the purpose of

the study and were told that participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Inclusion criteria were women aged 30 and over. Women with a history of

breast cancer were excluded from the study.

Procedure

The study was conducted in a hospital, medical ofces, and apartment

complexes. Women who agreed to take part in the study were provided with

a self-administered questionnaire that took 15 to 20 minutes to complete.

Screening behavior was identied in response to questions concerning BSE,

CBE, and mammography.

Instrument

The questionnaire included questions regarding demographic characteristics,

breast cancer screening behavior, attitudes toward mammography, and

stages of change for mammography. Age was categorized into three

groups: 30 to 34, 35 to 39, and 40+ years. Questions regarding education

(middle school, high school, or college), marital status (married or not

married), and employment (employed or not employed) also were included.

Socioeconomic status was categorized into three groups according to

monthly income: <2000000, 2000000 to <3000000, and 3000000 won

(< $2,135, $2,135 to 3,202, and $3202 [USD]).

Women were asked whether they had ever had a CBE or mammogram

and whether they were practicing monthly BSE. The questions were

answered by checking yes or no. BSE was categorized as monthly,

irregular, or never had.

Attitude (pros, cons, and decisional balance) toward mammography and

the ve changes in attitude toward mammography screening were measured

using an instrument developed by Rakowski and colleagues (1997) and

translated by Lee (2003). This scale has 13 items and consists of two subscales

that represent the positive (pros, six items) and negative (cons, seven items)

aspects of mammography screening. The pros include statements regarding

the benets of mammograms, such as, Having a mammogram every year

or two will give me a feeling of control over my health. The cons include

negative statements about mammograms, such as, Mammograms have a

high chance of leading to breast surgery that is not needed. Responses were

measured on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to

5 (strongly agree). Scores on the pros and cons subscale are calculated

by averaging the six pro and seven con items, respectively. The possible

score for pros ranged from 6 to 30, with a higher score indicating a more

favorable view of mammography. Scores on the cons subscale are calculated

Korean Womens Attitudes Toward Mammography 155

by averaging the seven con items. The possible score for cons ranged

from 7 to 35, with a higher score indicating a more unfavorable view of

mammography. The validity for pros and cons has been established (Lee,

2003; Rakowski et al., 1997). The reliability of the original scales was.74 for

pros and.73 for cons. The reliability of the translated scales was.74 for pros

and.72 for cons (Lee, 2003) and.77 and.69 for pros and cons, respectively,

in this study. Scores on pros and cons were converted into standardized

T scores (M = 50, SD = 10), and then decisional balance was calculated

by subtracting the T score for the cons scale from the T score for the

pros scale. Positive values of decisional balance reect a globally favorable

attitude toward mammography, and negative values reect an unfavorable

attitude.

The stages of change for mammography screening were examined

using an algorithm that has ve stages: precontemplation, contemplation,

relapse, action, and maintenance (Lee, 2003). Each stage of change denes

individuals readiness to alter their behavior based on actions they have taken

and their future plans. Women were classied in the precontemplation stage

if they reported never having had a mammogram and were not planning

to have one that year. Women were classied in the contemplation stage

if they had never received a mammogram but were planning to have one

within a year. Women were considered relapsed if they had received a

mammogram previously and were not planning to have one within a year.

Women were classied in the action stage if they had had a mammogram

and were planning to have another within a year. Women were dened as

regular users in the maintenance stage if they had received a mammogram

regularly and were planning to have another within a year.

At the end of the questionnaire, participants were asked to describe

from one to three barriers that prevent them from following recommended

guidelines for mammography screening.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS for Windows program (version 12.0).

Attitude toward mammography, distribution of the ve stages of change,

and selected demographic factors were expressed using descriptive statistics

that included frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations.

Cronbachs alpha was used to measure internal consistency for the scales

on each instrument. One-way analysis of variance was performed to assess

differences in mean scores of pros and cons in the different stages of

mammography adoption, and post-hoc analysis was used to determine at

which stages mean differences existed. Content analysis was used for analysis

of the open-ended questionnaire to determine barriers that prevent women

from obtaining mammography exams.

156 H. S. Kang et al.

The current breast cancer screening guidelines of the Korean Breast

Cancer Society and Korean National Cancer Center recommend that women

aged 35 years and older should have a CBE and women aged 40 years and

older should have regular mammograms. Based on recommended breast

cancer screening guidelines, we analyzed CBE only in women aged 35 and

over and mammography screening behavior in women aged 40 years and

over.

FINDINGS

A total of 328 women participated in the study. The average age was

37.69 years (SD = 6.09), with a range of 30 to 61 years. Two-thirds

of the participants (66.8%; n = 219) had at least a college education,

and approximately one-third (30.2%) had a high school education. Most

participants were married (89.6%, n = 294), with 30% reporting a monthly

household income below 2,000,000 won (1,000 won is equivalent to

approximately U.S. $1), 30.4% reporting an income of between 2,000,000

and 3,000,000 won, and 39.6% reporting an income of more than 3,000,000

won. Over half of the participants (52.7%) were employed.

BSE, CBE, and Mammography Behaviors

Only 2.7% of women reported following recommended screening guidelines

for monthly BSE, 62.2% practiced BSE irregularly, and 35% had never

performed a BSE. The majority of participants had never had a CBE, and

only 25.7% (n = 53) of women aged 35 years and older had ever received a

CBE. Among participants aged 40 years and older, almost half (48.3%) had

never had a mammogram.

Stages of Change

Among women aged 40 years and older, 30% (n = 36) were precontempla-

tors, 18.3% (n = 22) were contemplators, 23.3% (n = 28) were in the relapse

stage, 13.3% (n = 16) were in the action stage, and 15% (n = 18) were in

the maintenance stage.

Attitude (Pros, Cons, and Decisional Balance)

The item mean scores for pros, cons, and decisional balance were 3.48

(SD = .63), 2.81 (SD = .67), and 1.66 (SD = 16.19), respectively. The

mean scores for women aged 3034, 3539, and 40 and over were 3.35

(SD = .56), 3.57 (SD = .56), and 3.54 (SD = .71) for pros and 2.83 (SD

= .63), 2.84 (SD = .69), and 2.76 (SD = .71) for cons, respectively. There

Korean Womens Attitudes Toward Mammography 157

were statistically signicant differences only in pros among three age groups

(F = 4.06, p = .018). Tukeys post-hoc tests revealed that the pro scores of

30- to 34-year-olds were signicantly lower than that of 35- to 39-year-old

age groups ( p = .047). The scores for decisional balance varied from 6.89

to 15.52.

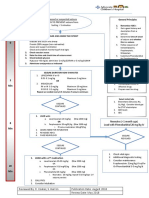

Pros and Cons Within the Stages of Change

There were signicant differences in pros (F = 5.175, p = .001) and cons (F

= 3.357, p = .012) across the ve stages of change for mammography (Table

1). Tukeys post-hoc tests revealed that individuals in the precontemplation

stage had a signicantly lower mean pro score than those in the maintenance

( p< .0001) stage. In contrast, individuals in the precontemplation stage had

a signicantly higher mean con score than those in the maintenance ( p =

.030) stage. Mean T-scores of pros increased from the precontemplation to

the maintenance stage. The scores of decisional balance varied from 6.89 in

the precontemplation stage to 15.52 in the maintenance stage. The crossover

occurred between precontemplation and contemplation stage.

Perceived Mammography Screening Barriers

Participants were asked to describe barriers that prevented them from having

regular mammograms. A belief that an absence of symptoms means that there

is no need for a breast examination was the most cited reason, followed by

the high cost of breast cancer screening, lack of time, lack of information,

embarrassment, fear about x-rays and test results, reliance on BSE, and

discomfort or pain (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The ndings from this study indicate that most Korean women perform BSE

irregularly or not at all. According to the recent American Cancer Society

guidelines for breast cancer screening (Smith et al., 2003), it is acceptable

for women to choose not to perform BSE because the ability of this method

to reduce breast cancer mortality remains controversial. Helping women to

gain familiarity with their own breast composition and encouraging women

to be aware of changes in their breasts may be more effective than BSE.

Furthermore, the importance of recognizing and reporting these changes, as

well as any symptoms, to a health professional should be emphasized.

There is a paucity of studies that explore CBE in Korean women. It also

has been difcult to assess CBE performance. Our estimate of the percentage

of Korean women who have ever received a CBE, however, was far below

that of Korean American women (53%; Lee, Fogg, & Sadler, 2006). There

T

A

B

L

E

1

P

r

o

s

,

C

o

n

s

,

a

n

d

D

e

c

i

s

i

o

n

a

l

B

a

l

a

n

c

e

A

c

r

o

s

s

S

t

a

g

e

s

o

f

C

h

a

n

g

e

(

N

=

1

2

0

)

5

s

t

a

g

e

s

o

f

r

e

a

d

i

n

e

s

s

t

o

C

h

a

n

g

e

P

r

e

c

o

n

t

e

m

p

l

a

t

i

o

n

C

o

n

t

e

m

p

l

a

t

i

o

n

R

e

l

a

p

s

e

A

c

t

i

o

n

M

a

i

n

t

e

n

a

n

c

e

(

n

=

3

6

)

(

n

=

2

2

)

(

n

=

2

8

)

(

n

=

1

6

)

(

n

=

1

8

)

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

M

(

S

D

)

M

(

S

D

)

M

(

S

D

)

M

(

S

D

)

M

(

S

D

)

F

(

p

)

T

u

k

e

y

H

S

D

P

r

o

s

3

.

2

1

3

.

5

2

3

.

6

0

3

.

6

0

4

.

0

7

5

.

1

7

5

P

C

<

M

(

.

7

8

)

(

.

4

4

)

(

.

5

7

)

(

.

6

0

)

(

.

8

3

)

(

.

0

0

1

)

C

o

n

s

2

.

9

9

2

.

6

8

2

.

9

3

2

.

4

9

2

.

4

0

3

.

3

5

7

P

C

<

M

(

.

5

9

)

(

.

6

9

)

(

.

7

4

)

(

.

8

7

)

(

.

5

5

)

(

.

0

1

2

)

T

p

r

o

s

4

5

.

7

8

5

0

.

6

1

5

1

.

9

8

5

2

.

0

3

5

9

.

5

3

5

.

1

7

5

P

C

<

M

(

1

2

.

4

3

)

(

6

.

9

7

)

(

9

.

0

6

)

(

9

.

6

2

)

(

1

3

.

2

1

)

(

.

0

0

1

)

T

c

o

n

s

5

2

.

6

7

4

8

.

1

3

5

1

.

7

9

4

5

.

3

0

4

4

.

0

2

3

.

3

5

7

P

C

<

M

(

8

.

7

4

)

(

1

0

.

2

2

)

(

1

0

.

9

2

)

(

1

2

.

9

3

)

(

8

.

2

3

)

(

.

0

1

2

)

D

e

c

i

s

i

o

n

a

l

b

a

l

a

n

c

e

6

.

8

9

2

.

4

8

.

1

9

6

.

7

3

1

5

.

5

2

7

.

6

7

6

P

C

<

A

,

M

(

1

4

.

4

6

)

(

1

3

.

7

2

)

(

1

4

.

0

4

)

(

1

9

.

1

9

)

(

1

2

.

1

8

)

(

<

.

0

0

0

1

)

C

,

R

<

M

T

p

r

o

s

a

n

d

T

c

o

n

s

:

s

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

i

z

e

d

T

s

c

o

r

e

s

(

M

=

5

0

,

S

D

=

1

0

)

;

D

e

c

i

s

i

o

n

a

l

b

a

l

a

n

c

e

:

T

p

r

o

s

T

c

o

n

s

.

158

Korean Womens Attitudes Toward Mammography 159

TABLE 2 Perceived Mammography Screening Barriers (N = 208)

Barriers n (%)

No need for a breast exam and no symptoms 88 (30.6)

Cost of breast cancer screening 54 (18.8)

Lack of time 39 (13.5)

Lack of information 30 (10.4)

Embarrassment 25 (8.7)

Fear about x-ray and test results 22 (7.6)

Reliance on BSE 19 (6.6)

Discomfort/pain 11 (3.8)

are a few possible explanations for this. First, Korean doctors spend a small

amount of time examining each client and may not have enough time to

perform a CBE. Second, Korean women do not feel comfortable exposing

their breasts in an examination, especially to male doctors. A previous study

reported that Korean women feel shameful and humiliated during breast

cancer screening exams when the physician is male (Im, Park, Lee, & Yun,

2004). Thus, female clinicians should be made available to women who

are uncomfortable with male doctors. Clinician condence and comfort also

should be explored as potential barriers that prevent women from having a

CBE.

Although mammography is recommended for women aged 40 and

older, almost half of the participants in this age range had never had a

mammogram. This is far lower than the 60% screening rate proposed in the

Korea health plan 2010 (Korea National Institute of Health, 2005). Clinicians

should stress the importance of breast cancer screening and recommend

mammograms since they could have an important effect on whether women

initiate and maintain regular mammography screening (Hur, Kim, & Park,

2005; Rauscher, Hawley, & Earp, 2005). There were no signicant differences

in the con scores among age groups. Women between the ages of 30 and 34,

however, had the lowest pro scores. The benets of mammography should

be stressed when educating this age group.

As expected, women in the maintenance stage perceived fewer barriers

and more benets to mammography, and there was an association between

pros and cons and stage of change of mammography supporting previous

studies (Chamot et al., 2001; Lee, 2003; Otero-Sabogal et al., 2006). In

samples of Swiss women (Chamot et al., 2001), Korean women (Lee,

2003), and Filipino, Latino, African American, Chinese, and White women

(Otero-Sabogal et al., 2006), the pros were signicantly associated with stage

of adoption. In addition, positive mammography attitudes were strongly

associated with initiation of mammography among rural American women

(Rauscher et al., 2005), and perceived benets was one of the predictors of

stage of mammography adoption among rural Korean women (Hur, Kim, &

Park, 2005). Based on this study nding and those from previous studies, the

160 H. S. Kang et al.

pros of mammography appear to be a common factor associated with stage

of mammography adoption across cultures. These results show that one

strategy to increase mammography adoption is to improve attitudes toward

mammography, and women can benet from an education intervention to

raise awareness of benets of mammography.

Only the maintenance stage was differentiated from the precontem-

plation stage in this study, however, in contrast to ndings in previous

studies (Chamot et al., 2001). This may owe to differences in populations

or small samples. The proscons crossover was closer to the contemplation

stage, supporting a previous study of 909 Swiss women aged 40 to 80 years

(Chamot et al., 2001). But it was different from that of previous studies of

women in the United States, which showed crossover just before the action

stage (Prochaska, Velicer, et al., 1994). These discrepancies could be due to

differences in populations. This nding, however, supports that the crossover

always happened prior to the action stage (Prochaska, Velicer, et al., 1994).

More studies across various populations and a repeated study with Korean

women are needed.

Prochaska (1994) named approximately a 10 T-point (approximately

1.0 SD) increase in pros for progressing from the precontemplation stage

to the action stage as a strong principle and a 0.5-SD decrease in cons

for progressing from the precontemplation stage to the action stage as

a weak principle. Interestingly, the magnitude of the difference from

precontemplation to action in this study was 6.3 T points (0.63 SD) for

pros and 7.4 T points (0.74 SD) for cons. Results of this study partially

supported Prochaskas strong and weak principles of change. This result is

more consistent with the weak principle of change, although the magnitude

of decrease in cons is somewhat higher than predicted by the weak principal

of change. Further replication studies would be helpful.

Participants mentioned several barriers that prevented them from having

mammography exams. The most common reason was that they believed

that without any obvious signs or symptoms, a breast exam is not required.

This nding is consistent with previous reports that women who do not

experience breast symptoms are less likely to receive mammograms (Im et

al., 2004; Ogedegbe et al., 2005; Sabatino, Burns, Davis, Phillips, & McCarthy,

2006). It is important to educate women that the early stages of breast cancer

may preclude signs and symptoms and to emphasize that mammography can

detect cancer that is not yet palpable.

Cost was also one of the barriers identied by participants, supporting

previous ndings (Ko, Sadler, Ryujin, & Dong, 2003; McAlearney, Reeves,

Tatum, & Paskett, 2005; Sabatino et al., 2006). At the time the data for

this study were collected, women had to pay 50% of each mammography

exam. The cost for mammograms was lowered to a 30% copayment

in 2006, however, and cancer screening for low-income women is free.

Even so, health care providers cannot ignore the fact that cost may be

Korean Womens Attitudes Toward Mammography 161

a major barrier for some women. In addition, sonograms, recommended

when mammography results are ambiguous, are not covered by health

insurance. Sonograms are relatively common among young Oriental women

because their breast tissue is dense. Efforts to lower screening costs or to

expand health insurance coverage for breast cancer screening is needed

to lower the economic burden and promote participation in screening.

Several participants stated that lack of time and information were barriers to

mammography. Philippine women also considered lack of time as a barrier

(Ko et al., 2003). Many women work full time, and most Korean clinics

are open only during the week. Women who do not have time to make

an appointment during the week would benet from time made available

during lunch, evenings, or weekends.

Lack of knowledge is also a major barrier to breast cancer screening

(Guerra, Krumholz, & Shea, 2005; Ogedegbe et al., 2005). October is

national breast cancer awareness month in Korea, as well as in many

Western countries. Many free public educational programs are offered,

and events such as a fund-raising marathon, free mobile mammography

examinations, and pink ribbon festivals are held to raise breast cancer

awareness. Even though these campaigns are helpful, some women who

need regular screening are not being reached. Thus, more efforts are required

to disseminate information about the importance of early breast cancer

screening.

Previous studies have reported that many women are not comfortable

exposing their breasts to or being touched by male technicians during

mammography exams (Im, Lee, & Park, 2002; Ogedegbe et al., 2005; Poulos

& Llewellyn, 2005; Sharp et al., 2003). Arrangements should be made to

have more female technicians to support women who are reluctant to have

their mammography exams conducted by males. Discomfort and pain during

mammography also can prevent women from returning for follow-up or

future exams (Ogedegbe et al., 2005; Sabatino et al., 2006; Sharp et al., 2003).

It is important to train technicians to be gentle and sensitive to womens

feelings. Fear about x-ray and test results is another barrier identied in

the literature and supported by this studys results. Our ndings support

a previous study that found that women fear exposure to x-rays as well

as the chance of nding cancer (Thompson, Montano, Mahloch, Mullen, &

Taylor, 1997). When educating women, the effects of the x-rays used in

mammography should be clearly explained.

One limitation of this study is that it was restricted to a convenience

sample of a small number of women, and results do not necessarily apply

to women in the broader Korean population. We also did not differentiate

between high- and low-risk groups. In spite of these limitations, this study

provides useful information for developing strategies to provide appropriate

screening intervention, patient education, breast cancer screening behavior

counseling, and changes in Korean health policy.

162 H. S. Kang et al.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of participants in this study did not receive regular breast cancer

screening, which supports the need to promote breast cancer awareness

among Korean women. Breast cancer screening can be encouraged by

emphasizing the benets of regular screening and decreasing the barriers.

The results of this study support the literature in regard to barriers

that prevent Korean women from following the recommended guidelines

for mammography. A salient issue regarding whether to have regular

mammograms is the value of early detection. Thus, it is important to

raise awareness of regular breast cancer screening, decrease the barriers

that prevent women from having mammograms, and reach out to women

who are in need of more education and assistance with payment for this

screening procedure. Disseminating information more assertively through

mass media, such as television, radio, newspapers, magazines, the Internet,

and mobile phones, is one way to raise awareness of important health

concerns. Lowering the cost of screening and using more women clinicians

or technicians also would be helpful to women who prefer them. Strategies to

promote screening would be more effective if cultural beliefs toward breast

cancer and screening were considered. Additional studies with larger samples

need to be conducted to explore barriers that prevent Korean women from

having CBE and mammography, particularly among women aged 40 years

and older.

The results of this study provide additional support for constructs of

the transtheoretical model of behavior change as they apply to screening

mammography. The results of this study indicate that nurses should keep

in mind that there are various barriers to mammography screening when

promoting mammography and educating clients about its benets; the

educational material should include information on barriers. Findings also

indicate that efforts at different levels, both personal and intrapersonal,

should be made to promote breast cancer screening.

REFERENCES

Ahn, S., Yoo, K. Y., & Korean Breast Cancer Society, (2006). Chronological changes

of clinical characteristics in 31115 new breast cancer patients among Koreans

during 19962004. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 99(2), 209214.

American Cancer Society. (2001). Breast cancer facts & gures

20012002. Retrieved November 10, 2006, from http://www.cancer.org/

docroot/STT/content/STT 1x Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 20012002.asp

Bouchardy, C., Morabia, A., Verkooijen, H. M., Fioretta, G., Wespi, Y., & Schafer, P.

(2006). Remarkable change in age-specic breast cancer incidence in the Swiss

canton of Geneva and its possible relation with the use of hormone replacement

therapy. BMC Cancer, 6, 78.

Korean Womens Attitudes Toward Mammography 163

Chamot, E., Charvet, A. I., & Perneger, T. V. (2001). Predicting stages of adoption of

mammography screening in a general population. European Journal of Cancer,

37, 18691877.

Choi, J., Kim, Y. J., Shin, H. R., Noh, D. Y., & Yoo, K. Y. (2005). Long-term prediction

of female breast cancer mortality in Korea. Asian-Pacic Journal of Cancer

Prevention, 6(1), 1621.

Guerra, C. E., Krumholz, M., & Shea, J. A. (2005). Literacy and knowledge,

attitudes and behavior about mammography in Latinas. Journal Health Care

Poor Underserved, 16(1), 152166.

Hur, H. K., Kim, G. Y., & Park, S. M. (2005). Predictors of mammography participation

among rural Korean women age 40 and over. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi, 35(8),

14431450.

Im, E., Lee, E. O., & Park, Y. S. (2002). Korean womens breast cancer experience.

Western Journal of Nursing Research, 24(7), 751771.

Im, E., Park, Y. S., Lee, E. O., & Yun, S. N. (2004). Korean womens attitudes toward

breast cancer screening tests. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(6),

583589.

Ko, C., Sadler, G., Ryujin, L., & Dong, A. (2003). Filipina American womens

breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors. Public Health,

3(1), 2732.

Korea National Institute of Health. (2005). Health People 2010. Seoul: Authors.

Lee, Y. J. (2003). Predicting factors corresponding to the stage of adoption

for mammography based on transtheoretical model. Unpublished doctoral

dissertation, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

Lee, E. E., Fogg, L. F., & Sadler, G. R. (2006). Factors of breast cancer screening

among Korean immigrants in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health, 8(3),

223233.

McAlearney, A. S., Reeves, K. W., Tatum, C., & Paskett, E. D. (2005). Perceptions

of insurance coverage for screening mammography among women in need of

screening. Cancer, 103(12), 24732480.

National Cancer Center. (2006). Cancer information (2nd ed.). Goyangsi: Korea

National Cancer Center.

Ogedegbe, G., Cassells, A. N., Robinson, C. M., Duhamel, K., Tobin, J. N., Sox, C.

H., et al. (2005). Perceptions of barriers and facilitators of cancer early detection

among low-income minority women in community health centers. Journal of

the National Medical Association, 97(2), 162170.

Otero-Sabogal, R., Stewart, S., Shema, S. J., & Pasick, R. J. (2006). Ethnic differences

in decisional balance and stages of mammography adoption. Health Education

& Behavior,. [Serial online]. August 4, 2006; doi:10.1177/1090198105277854

Poulos, A., & Llewellyn, G. (2005). Mammography discomfort: A holistic perspective

derived from womens experiences. Radiography, 11, 1725.

Prochaska, J. O. (1994). Strong and weak principles for progressing from precontem-

plation to action on the basis of twelve problem behaviors. Health Psychology,

13(1), 4751.

Prochaska, J. O., Norcross, J. C., & DiClemente, C. C. (1994). Changing for good.

New York: William Morrow.

164 H. S. Kang et al.

Prochaska, J., Velicer, W., Rossi, J., Goldstein, M., Marcus, B., Rakowski, W., et

al. (1994). Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors.

Health Psychology, 13(1), 3946.

Rakowski, W., Clark, M. A., Pearlman, D. N., Ehrich, B., Rimer, B. K., Goldstein, M.

G., et al. (1997). Integrating pros and cons for mammography and Pap testing:

Extending the construct of decisional balance to two behaviors. Preventive

Medicine, 26(5), 664673.

Rauscher, G. H., Hawley, S. T., & Earp, J. L. (2005). Baseline predictors of initiation

vs. maintenance of regular mammography use among rural women. Preventive

Medicine, 40, 822830.

Sabatino, S., Burns, R., Davis, R., Phillips, R., & McCarthy, E. (2006). Breast cancer risk

and provider recommendation for mammography among recently unscreened

women in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 285291.

Sharp, P., Michielutte, R., Freimanis, R., Cunningham, L., Spangler, J., & Burnette,

V. (2003). Reported pain following mammography screening. Archives Internal

Medicine, 163(7), 833836.

Smigal, C., Jemal, A., Ward, E., Cokkinides, V., Smith, R., Howe, H., et al. (2006).

Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: Update 2006. CA: A Cancer

Journal of Clinicians, 56, 168183.

Smith, A. A., Saslow, D., Sawyer, K. A., Burke, A., Burke, W., Costanza, M. E., et al.

(2003). American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: Update

2003. CA: A Cancer Journal of Clinicians, 53, 141169.

Spencer, L., Pagell, F., & Adams, T. (2005). Applying the transtheoretical model to

cancer screening behavior. Ame J Health Behavior, 29, 3656.

Sung, N., Park, E., Shin, H., & Choi, K. (2005). Participation rate and related socio-

demographic factors in the national cancer screening program. J Prev Med Public

Health, 38(1), 93100.

Thomas, E. C. (2004). African American womens breast memories, cancer beliefs,

and screening behaviors. Cancer Nursing, 27(4), 295302.

Thompson, B., Montano, D., Mahloch, J., Mullen, M., & Taylor, V. (1997). Attitudes

and beliefs toward mammography among women using an urban public

hospital. Journal of Health Care Poor Underserved, 8(2), 186201.

Tu, S., Yasui, Y., Kuniyuki, A., Schwartz, S., Jackson, J., & Taylor, V. (2002). Breast

cancer screening: Stages of adoption among Cambodian American women.

Cancer Detection and Prevention, 26, 3341.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Persistent Fear and Anxiety Can Affect Young Childrens Learning and Development PDFDocument16 pagesPersistent Fear and Anxiety Can Affect Young Childrens Learning and Development PDFCristina AlexeevPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Emergency Severity IndexDocument114 pagesEmergency Severity Indexpafin100% (3)

- Voice Production in Singing and SpeakingBased On Scientific Principles (Fourth Edition, Revised and Enlarged) by Mills, Wesley, 1847-1915Document165 pagesVoice Production in Singing and SpeakingBased On Scientific Principles (Fourth Edition, Revised and Enlarged) by Mills, Wesley, 1847-1915Gutenberg.org100% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Manage Odontogenic Infections Stages Severity AntibioticsDocument50 pagesManage Odontogenic Infections Stages Severity AntibioticsBunga Erlita RosaliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ongoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedDocument18 pagesOngoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Antenatal & Postnatal Care: 1. General InformationDocument7 pagesAntenatal & Postnatal Care: 1. General InformationanishnithaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vroom Tips: Brain Building BasicsDocument7 pagesVroom Tips: Brain Building BasicsJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Fundamentals of Tooth Preparation Periodontal AspectsDocument74 pagesFundamentals of Tooth Preparation Periodontal AspectsVica Vitu100% (3)

- 3.mechanical VentilationDocument33 pages3.mechanical Ventilationisapatrick8126Pas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative Report On School Nursing - EditedDocument16 pagesNarrative Report On School Nursing - EditedAbby_Cacho_9151100% (2)

- Ozone Therapy in DentistryDocument16 pagesOzone Therapy in Dentistryshreya das100% (1)

- UrinalysisDocument43 pagesUrinalysisJames Knowell75% (4)

- Clinical Evoked PotentialsDocument13 pagesClinical Evoked PotentialsHerminaElenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Growth Chart IDocument1 pageGrowth Chart IJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Placement Changes and Emergency Department Visits in The First Year of Foster CareDocument9 pagesPlacement Changes and Emergency Department Visits in The First Year of Foster CareJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Effective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementDocument12 pagesEffective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Status EpileticusDocument2 pagesStatus EpileticusJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Oral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportDocument10 pagesOral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Identifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportDocument11 pagesIdentifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Considerations Related To The Behavioral Manifestations of Child MaltreatmentDocument15 pagesClinical Considerations Related To The Behavioral Manifestations of Child MaltreatmentJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Making The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesDocument5 pagesMaking The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- IJMEDocument7 pagesIJMEJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Ckeck List Operacional - Usda Inst Saude e SegDocument3 pagesCkeck List Operacional - Usda Inst Saude e SegQualidade CooperalfaPas encore d'évaluation

- Difficult Patient Encounters: Assessing Pediatric Residents' Communication Skills Training NeedsDocument19 pagesDifficult Patient Encounters: Assessing Pediatric Residents' Communication Skills Training NeedsJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- i-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLDocument1 pagei-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Jpeds Aom 208Document3 pagesJpeds Aom 208Jesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Cbig Cross-ReportingDocument25 pagesCbig Cross-ReportingJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Suidi Oklahoma ProviderDocument28 pagesSuidi Oklahoma ProviderJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- SB773Document257 pagesSB773Jesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsDocument8 pagesWhat Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Vroom Tips: Brain Building BasicsDocument16 pagesVroom Tips: Brain Building BasicsJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- dBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGDocument4 pagesdBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- 2018 OdhhsDocument124 pages2018 OdhhsJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Child Abuse Neglect Prevention OklahomaDocument44 pagesChild Abuse Neglect Prevention OklahomaJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceDocument40 pagesPreventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Recommendations For Preventive Pediatric Health Care: Bright Futures/American Academy of PediatricsDocument2 pagesRecommendations For Preventive Pediatric Health Care: Bright Futures/American Academy of PediatricsJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Domestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Document44 pagesDomestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Jesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- COVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixDocument1 pageCOVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixJesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Document1 pageIntimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Jesse M. MassiePas encore d'évaluation

- Life Calling Map Fillable FormDocument2 pagesLife Calling Map Fillable Formapi-300853489Pas encore d'évaluation

- Concrete MSDS 1 PDFDocument5 pagesConcrete MSDS 1 PDFmanil_5100% (1)

- Radial Club Hand TreatmentDocument4 pagesRadial Club Hand TreatmentAshu AshPas encore d'évaluation

- MMMM 3333Document0 pageMMMM 3333Rio ZianraPas encore d'évaluation

- Maxillofacial Privileges QGHDocument4 pagesMaxillofacial Privileges QGHSanam FaheemPas encore d'évaluation

- CapstoneDocument40 pagesCapstoneDevanshi GoswamiPas encore d'évaluation

- A Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen PlanusDocument1 pageA Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen Planus600WPMPOPas encore d'évaluation

- HouseflyDocument16 pagesHouseflyRitu Puri50% (2)

- Proctor Tobacco History Report Canadian Trial Rapport - Expert - ProctorDocument112 pagesProctor Tobacco History Report Canadian Trial Rapport - Expert - Proctorkirk_hartley_1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reverse Optic Capture of The SingleDocument10 pagesReverse Optic Capture of The SingleIfaamaninaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bagian AwalDocument17 pagesBagian AwalCitra Monalisa LaoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 16-17 - Opioids AnalgesicsDocument20 pagesLecture 16-17 - Opioids AnalgesicsJedoPas encore d'évaluation

- Resume Massage Therapist NtewDocument2 pagesResume Massage Therapist NtewPartheebanPas encore d'évaluation

- MedAspectsBio PDFDocument633 pagesMedAspectsBio PDFDuy PhúcPas encore d'évaluation

- 2014 Windsor University Commencement Ceremony PROOFDocument28 pages2014 Windsor University Commencement Ceremony PROOFKeidren LewiPas encore d'évaluation

- WHO 1991 128 PagesDocument136 pagesWHO 1991 128 PagesLilmariusPas encore d'évaluation

- Bradford Assay To Detect Melamine ConcentrationsDocument3 pagesBradford Assay To Detect Melamine ConcentrationsVibhav SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Dance BenefitsDocument9 pagesDance Benefitsapi-253454922Pas encore d'évaluation

- Patch ClampDocument4 pagesPatch ClampXael GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dengulata KosamDocument3 pagesDengulata KosamChina SaidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rangkuman by Yulia VionitaDocument21 pagesRangkuman by Yulia VionitaRizqi AkbarPas encore d'évaluation