Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

West Des Moines Valley Dahm Basler Neg Wake Forest Round1

Transféré par

DwaynetherocCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

West Des Moines Valley Dahm Basler Neg Wake Forest Round1

Transféré par

DwaynetherocDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Topicality

Our interpretation is that an affirmative should defend a topical action by the USfg as the

endpoint of their advocacy. This does not mandate roleplaying, immediate fiat or any

particular means of impact calculus.

The resolution indicates affs should advocate topical government change

Ericson 3 (Jon M., Dean Emeritus of the College of Liberal Arts California Polytechnic U., et

al., The Debaters Guide, Third Edition, p. 4)

The Proposition of Policy: Urging Future Action In policy propositions, each topic contains certain key elements, although they have

slightly different functions from comparable elements of value-oriented propositions. 1. An agent doing the acting ---The United

States in The United States should adopt a policy of free trade. Like the object of evaluation in a proposition of value, the

agent is the subject of the sentence. 2. The verb shouldthe first part of a verb phrase that urges action. 3.

An action verb to follow should in the should-verb combination. For example, should adopt here means to put a program or

policy into action though governmental means. 4. A specification of directions or a limitation of the action desired. The phrase

free trade, for example, gives direction and limits to the topic, which would, for example, eliminate consideration of increasing tariffs, discussing diplomatic

recognition, or discussing interstate commerce. Propositions of policy deal with future action. Nothing has yet occurred. The entire debate is

about whether something ought to occur. What you agree to do, then, when you accept the affirmative side in such a debate is to

offer sufficient and compelling reasons for an audience to perform the future action that you propose.

First, a limited topic of discussion that provides for equitable ground is key to productive

inculcation of decision-making and advocacy skills in every and all facets of life---even if

their position is contestable thats distinct from it being valuably debatable---we do NOT

force them back in the closet---this still provides room for flexibility, creativity, and

innovation, but targets the discussion

Steinberg & Freeley 8 *Austin J. Freeley is a Boston based attorney who focuses on criminal,

personal injury and civil rights law, AND **David L. Steinberg , Lecturer of Communication

Studies @ U Miami, Argumentation and Debate: Critical Thinking for Reasoned Decision

Making pp45-

Debate is a means of settling differences, so there must be a difference of opinion or a conflict of

interest before there can be a debate. If everyone is in agreement on a tact or value or policy, there is no need

for debate: the matter can be settled by unanimous consent. Thus, for example, it would be

pointless to attempt to debate "Resolved: That two plus two equals four," because there is simply

no controversy about this statement. (Controversy is an essential prerequisite of debate. Where there is no

clash of ideas, proposals, interests, or expressed positions on issues, there is no debate. In addition, debate cannot

produce effective decisions without clear identification of a question or questions to be

answered. For example, general argument may occur about the broad topic of illegal

immigration. How many illegal immigrants are in the United States? What is the impact of illegal immigration

and immigrants on our economy? What is their impact on our communities? Do they commit crimes? Do they take jobs from

American workers? Do they pay taxes? Do they require social services? Is it a problem that some do not speak English? Is it the

responsibility of employers to discourage illegal immigration by not hiring undocumented workers?

Should they have the opportunity- to gain citizenship? Docs illegal immigration pose a security threat to our country? Do illegal

immigrants do work that American workers are unwilling to do? Are their rights as workers and as

human beings at risk due to their status? Are they abused by employers, law enforcement, housing, and businesses? I low are their families

impacted by their status? What is the moral and philosophical obligation of a nation state to maintain its borders? Should we build

a wall on the Mexican border, establish a national identification can!, or enforce existing laws against employers? Should

we invite immigrants to become U.S. citizens? Surely you can think of many more concerns to be

addressed by a conversation about the topic area of illegal immigration. Participation in

this "debate" is likely to be emotional and intense. However, it is not likely to be

productive or useful without focus on a particular question and identification of a line

demarcating sides in the controversy. To be discussed and resolved effectively, controversies must be

stated clearly. Vague understanding results in unfocused deliberation and poor

decisions, frustration, and emotional distress, as evidenced by the failure of the United States Congress

to make progress on the immigration debate during the summer of 2007. Someone

disturbed by the problem of the growing underclass of poorly educated, socially

disenfranchised youths might observe, "Public schools are doing a terrible job! They are

overcrowded, and many teachers are poorly qualified in their subject areas. Even the best teachers can do little more than struggle to

maintain order in their classrooms." That same concerned citizen, facing a complex range of issues, might arrive at an unhelpful decision,

such as "We ought to do something about this" or. worse. "It's too complicated a problem to deal with." Groups of concerned

citizens worried about the state of public education could join together to express their

frustrations, anger, disillusionment, and emotions regarding the schools, but without a focus for their

discussions, they could easily agree about the sorry state of education without finding

points of clarity or potential solutions. A gripe session would follow. But if a precise

question is posedsuch as "What can be done to improve public education?"then a more profitable area of

discussion is opened up simply by placing a focus on the search for a concrete solution

step. One or more judgments can be phrased in the form of debate propositions, motions

for parliamentary debate, or bills for legislative assemblies. The statements "Resolved: That the federal

government should implement a program of charter schools in at-risk communities" and "Resolved: That the state of Florida should adopt a

school voucher program" more clearly identify specific ways of dealing with educational problems in a manageable form, suitable for debate.

They provide specific policies to be investigated and aid discussants in identifying points

of difference. To have a productive debate, which facilitates effective decision making

by directing and placing limits on the decision to be made, the basis for argument should be

clearly defined. If we merely talk about "homelessness" or "abortion" or "crime'* or

"global warming" we are likely to have an interesting discussion but not to establish

profitable basis for argument. For example, the statement "Resolved: That the pen is

mightier than the sword" is debatable, yet fails to provide much basis for clear

argumentation. If we take this statement to mean that the written word is more effective than physical force for some purposes, we

can identify a problem area: the comparative effectiveness of writing or physical force for a specific purpose. Although we now

have a general subject, we have not yet stated a problem. It is still too broad, too loosely worded to promote well-

organized argument. What sort of writing are we concerned withpoems, novels, government documents, website

development, advertising, or what? What does "effectiveness" mean in this context? What kind of physical force is being

comparedfists, dueling swords, bazookas, nuclear weapons, or what? A more specific question might be. "Would a mutual defense treaty

or a visit by our fleet be more effective in assuring Liurania of our support in a certain crisis?" The basis for argument

could be phrased in a debate proposition such as "Resolved: That the United States should enter into a mutual

defense treatv with Laurania." Negative advocates might oppose this proposition by arguing that fleet maneuvers would be a better solution.

This is not to say that debates should completely avoid creative interpretation of the

controversy by advocates, or that good debates cannot occur over competing interpretations of

the controversy; in fact, these sorts of debates may be very engaging. The point is that

debate is best facilitated by the guidance provided by focus on a particular point of

difference, which will be outlined in the following discussion.

Ocean education is crucial to the environment, scientific literacy and requires a focus on

policymaking. We have to create student networks of global ocean advocates, a purely local

focus ignores the fundamental interconnectedness of the ocean

Sosnowski 13 Sosnowski (Ford Apprentice Scholar in Marine Science a Eckerd College, Researcher at National Systematics Laboratory,

Smithsonian Institutions Natural Museum of Natural History) 13 (Amanda, Ocean Literacy: Fishing Down the Food Web, April 28, 2013,

http://www.eckerd.edu/academics/ford/files/13/AmandaSosnowski.pdf)

There is a desperate need for the ability to understand science, or scientific literacy, in todays society. Matters like technologys progress,

understanding the natural world around us, and environmental issues on a global scale all require a science literate public, as well as officials

supporting this concept. Global matters concerning the natural world are the source of practical understandings needed for informed decisions

in our everyday lives, such as health, sustenance, environmental sustainability, etc. Scientific literacy is an important way to note that science is

not isolated from other disciplines in our lives; it generally provides context for concepts in different disciplines. Perhaps the most

valuable skill gained from scientific literacy is the ability to understand concepts across different

subjects and make connections within a particular subject area, essentially producing a more

robust comprehension of information. It is necessary to revisit my introduction and why I understood ocean sciences to be a

great field to study: water is the basis for all life on earth. With that said, the ability to understand science, the study of the

physical and natural world, must be linked with the ability to understand the oceans, which contain the

basis for all life on earth. The question then arises: can scientific literacy exist without ocean literacy? Strange et al. (2007) argued:

Research consistently affirms the ocean's vital role in maintaining the unity of our world. Without its vast ocean, Earth could be inhospitably cold

like Mars or a stifling greenhouse like Venus. On the other hand, the interconnectedness of the ocean and the atmosphere has had negative

impacts. Ocean waters absorb airborne industrial chemicals that are carried thousands of miles from their source to the Arctic region. These

pollutants are found in the bodies of top predators such as polar bears, which absorb the chemicals through their diet of fish and seals.

Whether we live on the coast or inland, eat seafood or not, humans are inextricably tied to the ocean. Thus

the scientifically literate citizens we grow in our schools must become familiar with ocean issues

that may or may not be happening in their own backyards. The simple answer to this question is, no,

scientific literacy and ocean literacy are inextricably intertwined. While both scientific literacy and ocean literacy

are vital skills needed in todays society, most significant science concepts can be demonstrated through ocean examples such as biodiversity,

geography, climate, etc. The National Marine Educators Association has defined an ocean literate person as someone who has the ability to

understand the essential principles and fundamental concepts about the ocean, can communicate this information in a meaningful way, and make

informed and responsible decisions regarding the ocean and its resources (Strang et al., 2011). Because the oceans are at the

crux of extremely important environmental issues of our time, such as global climate change and the future health of our

planet, it is necessary to employ ocean literacy as the forefront form of scientific literacy.

Kritik

The Aff has failed in their goal of providing an accurate and effective genealogy of the

Middle Passage, and modern political antagonisms. Their narrative of the slave is one of a

countless series of stand-ins for the Animal, contingently reduced to something less than

humanity in order to justify violence. The very idea of the exposure to gratuitous

violence is the basic condition of the Animal in modern society and makes the world

fundamentally unethical and endless massacres inevitable

Sanbomatsu (associate professor of philosophy at Worchester Polytechnic) 11

(Jon, Introduction to Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, pg. 10-13)

This episteme to borrow Foucaults term, has subtended and conditioned the whole of civilization

from its beginning, providing the very basis of positive human culture. For centuries, our

sciences and systems of knowledge have conspired to divide sentient life, conscious being-in-

the-world, into two neat, mutually exclusive, and utterly fraudulent halves"the human"

versus "the rest" other, we end up disavowing our own humanity (itself, after all, a form of animality)

embracing a "machine civilization" based in death-fetishism. "How is it possible" Reich wondered, "that [man]

does not see the damages (psychic illnesses, biopathies, sadism, and wars) to his health, culture, and mind that

23 are caused by this biologic renunciation?" It is striking that Reich, Adorno, and Horkheimer, all of whom

were per- sonally forced to flee Germany by Hitler, had no qualms about comparing the human treatment of

animals to the treatment of Jews and other enemies of the 24 ;Third Reich under fascism. After the war,

Adorno famously wrote that "Auschwitz begins wherever someone looks at a slaughterhouse and

thinks: they're only animals," a once-obscure quote that recently has been given new life by animal

rights activists and sympathetic scholars. In fact, pointed com- parisons of our treatment of other animals to the

Nazis' treatment of the Jews and others in the Holocaust are peppered throughout Adorno's work, some- times

showing up in the most unexpected places (including a study of Beethoven's music). As Mendieta observes

here, Adorno drew an explicit link between Kant's denial of any meaningful subjectivity or

moral worth to ani- mals and the catastrophes of the twentieth century, including the rise of

National Socialism. "Nothing is more abhorrent to the Kantian," he wrote, "than a reminder of man's

resemblance to animals. This taboo is always at work when the idealist berates the materialist. Animals play

for the idealist system virtually the same role as the Jews for fascism?25 Indeed, is speciesism itself not a form

of fascism, perhaps even its paradig- matic or primordial form? The very word "massacre," Semelin

observes, originally meant "putting an animal to death": human massacres of other humans

have always been realized through the semiotic transposition of the one abject subject onto

the other. "Killing supposedly human animals' then becomes entirely possible."26 Adorno made a similar

point in Minima Mora- liat sixty years earlier: "The constantly encountered assertion that savages,

blacks, Japanese are like animals, monkeys for example, is the key to the pogrom. The

possibility of pogroms is decided in the moment when the gaze of a fatally-wounded animal falls on a human

being," What is crucial to bear in mind, however, as Victoria Johnson points out in her chapter here ("Ev-

eryday Rituals of the Master Race: Fascism, Stratification, and the Fluidity of Animal' Domination") the very

"power of such animal metaphors depends on a prior cultural understanding of other animals

themselves, as beings who are by nature abject, degraded, and hence worthy of

extermination." The animal, thus, rests at the intersection of race and caste systems. And nowhere is the link

between the human and nonhuman caste systems clearer than "in fascist ideology," for "no other discourse so

completely authorizes absolute violence against the weak," In our own contemporary society too, Johnson

emphasizes, we find daily life and meaning based on elaborate rituals in- tended to keep us from

acknowledging the violence we do to subordinate classes of beings, above all the animals. So numerous in fact

are the parallelssemiotic, ideological, psychological, historical, cultural, technical, and so forthbetween

the Nazis' extermination of the Jews and Roma and the routinized mass murder of nonhuman beings, that

Charles Pattersons recent book on the subject, Eternal Trehlinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust,

despite its strengths, only manages to scratch the surface of a topic whose true dimensions have yet to be

fathomed. In the ideological mechanisms used to legitimate killing, in the bad faith of the human beings who

collude with the killing through indifference or "ignorance of the facts," above all in the technologies of

organized mur- derpractices of confinement and control, modes of legitimation and decep- tion, methods of

elimination (gassing, shooting, clubbing, burning, vivisect- ing, and so on)the mass killing of animals today

cannot but recall the Nazi liquidation of European Jewry and Roma. The late Jacques Derrida observed that

"there are also animal genocides." he wrote with uncharacteristic moral sobriety: [T]he annihilation of certain

species is indeed in progress, but it is occurring through the organization and exploitation of an artificial,

infernal, virtually in- terminable survival, in conditions that previous generations would have judged

monstrous, outside of every supposed norm of a life proper to animals that are thus exterminated by means of

their continued existence or even overpopulation. As if, for example, instead of throwing people into ovens or

gas chambers (lets say Nazis) doctors and geneticists had decided to organize the overproduction and

overgeneration of Jews, gypsies, and homosexuals by means of artificial in- semination, so that, being more

numerous and better fed, they could be destined in always increasing numbers for the same hell, that of the

imposition of genetic experimentation or extermination by gas or fire. What would it mean for us to

come to terms with the knowledge that civilization, our whole mode of development and culture,

has been premised and built upon exterminationon a history experienced as "terror without end" (to

borrow a phrase from Adorno)? To dwell with such a thought would be to throw into almost

unbearable relief the distance between our narratives of inherent human dignity and grace

and moral superiority, on one side, and the most elemental facts of our actual social existence,

on the other. We congratulate ourselves for our social prog- ressfor democratic governance and

state-protected civil and human rights (however notional or incompletely defended)yet continue to

enslave and kill millions of sensitive creatures who in many biological, hence emotional and

cognitive, particulars resemble us. To truly meditate on such a contradiction is to comprehend our self-

understanding to be not merely flawed, but to be al- most comically delusional. Immanuel Kant dreamed of a

moral order in which we would all participate as equals in a "kingdom of ends" But it is time to ask

whether morality as such is even possible under conditions of universal bad faith and hidden

slaughter, in the same way that we might ask whether acts of private morality under National Socialism were

not compromised or diminished by the larger context in which they occurred.

Anti-blackness fails to explain the massacres of Messenians by the Spartans, Native

Americans by the Spanish, the Chinese by the Japanese, Roma and Jews by the Germans.

The Aff will doubtlessly say these were not structural antagonisms, they were merely

contingent slaughter but our argument is that everyone of these is emblematic of the

ongoing ontological division between human and animal and that everyone of these deaths

matter and should be mourned.

Johnson (associate professor of sociology at University of Missouri) 11

(Victoria, Everyday Rituals of the Master Race, in Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, pg. 203-4)

History is littered with episodes of the brutal exploitation and murder of groups that have

been portrayed as subhuman animals and therefore not de- serving of the moral and legal protections of

human beings. Going back as far as 300 BCE, Spartans turned the newly conquered

Messenians into a slave- serf class through rituals of subordination that required the

Messenians to wear "dog skins" to dance while drunk to humiliate themselves, and to be 1 hunted in an

annual war the Spartans declared on them. More recent exam- ples of the "animalization" of human

beings can be found throughout the co- lonial period, for instance in the European

characterization of Native Ameri- cans as "wild beasts," a view early Spanish explorers

adopted as they massacred entire towns, including women, children, and the elderly"not only

stabbing and dismembering" (de las Casas later described) "but cutting them to pieces 2 as if

dealing with sheep in the slaughter house." African human beings too were treated "like

animals"branded, muzzled, collared, bred, packed into small enclosures for transportation, and sold at

slave markets modeled after 3 cattle markets. Similarly, in the East, the Japanese characterized

the Chinese as subhuman and "animal"-like to justify the colonization of China and its

inhabitants in the early twentieth century. Thus the Japanese soldier who, later describing

how he felt pushing Chinese prisoners into a pit and setting them 4 on fire, said that it was

"identical to when he slaughtered pigs." Perhaps the best-known episode of the dehumanization

which is to say, animalizationof human populations was the Nazi extermination of Jews dur- 5 ing World

War Two. Scholars seeking to understand how engaging in acts of dehumanization "made sense" to the

perpetrators of atrocities have focused es pecially on the cultural narratives used by the Nazis to rationalize

their violence. According to Kenneth Burke, Hitlers war rhetoric constructed Jews through a "devil" function

that unified those who constituted absolute good in opposition to those who constituted absolute evil, and who

hence were beyond moral re- 6 demption. The more recent work of Felicity Rash has identified the ways that

Hitler used metaphor, metonymy, and personification to degrade opponents*! Not surprisingly these forms of

linguistic violence included numerous animal representations. Both Burke and Rash reveal a dualism

interwoven in Hitlers rhetoric between Aryans and "subordinate" beingsspecifically the Jews; whose very

nature was seen as being so fundamentally different from the "su- perordinate" Aryans as to constitute a

separate species. In Mein Kampf, Hitler depicts Jews as being biologically inferior: as unable to produce

culture, as lack- ing souls, as being less intelligent, and as being physically and mentally weaker than the

"master race." The latter term might as easily have been "the master 8 species." And in fact, Hitler

occasionally used the term "species" interchangeably with "race" in Mein Kampf . Such

examples could be multiplied. But there is another dimension to the "animalization" of human persons

that is often overlookednamely, that the power of such animal metaphors depends on a prior cultural

understanding of other animals themselves, as beings who are by nature abject, degraded,

and hence worthy of extermination. In fact, on examination we find that Nazi nar- ratives justifying the

domination of human subordinates are strikingly similar to beliefs about animals that are widely held to this

day, beliefs that human beings use to justify the exploitation and killing of nonhuman beings. For example,

defending the use of animals for experimentation, John Martin, a cardiovascular researcher and academic in

Great Britain, has argued that the superior moral status of human beings is sufficient justification for

vivisection and experimentation on primates. He argues that only human beings have the ability for abstract

thought and reflection, which allows us to learn over gen- 10 erations and to produce music and poetry. A

recent article in Christianity Today argued that "[h]umans alone have souls which confers upon them a unique

moral status. . . . Scriptures tells us that animals are soulless creatures 11 and will perish with the rest of

creation."

Their concept of Social Death prevents emancipation for all bodies. It plays into deeply

conservative notions of sociology that presume the social to be equivalent to the Human

and superior to the natural and that there exists a single, unitary social sphere that beings

can be ejected from by other humans. This dualism between social life and death is part of

a mode of thinking that makes oppression of billions of others possible.

Rejecting this way of thinking is a necessary prior step to addressing the destruction of

human and non-human animal life particularly for abjected Black and brown bodies

Taylor (Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Flinders University; PhD in Sociology from Manchester Metropolitan

University) 11

(Nik, Can Sociology Contribute To The Emancipation Of Animals?, Theorizing Animals: Rethinking Humanimal

Relations, pg. 209)

Social theory is littered with grand meta-theories which seek to reduce the complexities of social life to

something simple and, ulti- mately, explainable. Social life however is, in reality, messy and often refuses to

conform to this idealized view. Take, for example, our relationships with other animals. We eat them, wear

them, love them, live with them, abuse them, consider them family members, deify them, and much more.

Moreover, any individual in any one lifetime may do any, or all, of these with one, or many, animals. Our

relationships with other animals often defy categorization (as does much of social life) yet

for the most part we seek to explain and understand these relationships with recourse to

traditional social theories, now centuries old and having their roots in entirely different social sys- tems,

which maintain that we can, and should, neatly categorize social life. As social theory (and sociology in

particular) attempts to come to grips with 'the animal question' it is finding that a direct corollary of this is the

need to revisit 'the social question' as our current conceptions of animals are based on a belief in

the social-natural divide. Moreover it is precisely this divide which maintains current

oppressive animal practices. Within modernity, culture is cast as firm opposite, as 'Other,' to

nature. This "ideological fiction" (Haraway 1992, 13) is then embedded in such a way that it becomes the

taken-for-granted base of an epistemologically realist science which reiterates the 'truth' of these beliefs

axiomatically. These 'truths' are not limited to the justification of human domination of other

species but also include those of women and people of color. Furthermore this oppression of

Others is often inextricably interwoven. For example, Marjorie Spiegel (1988) documents how, historically,

African Americans were 'dehumanized' in order to justify their continued slavery. This was achieved, she

argues, largely by comparing them to negative stereotypes of non-human animals. Similarly Keith Thomas

points out that "once perceived as beasts people were likely to be treated accordingly. The ethic of human

domination removed animals from the sphere of concern. But it also legitimized the ill-treatment of humans

who were supposedly in an animal condition" (Thomas 1983, 44). More con- troversially, Patterson (2002)

points out the similarities in the justificatory rhetoric used by the Nazis and other eugenicists who historically

supported slavery and that used by modern proponents of animal use for human benefit. Whilst quick to

point out the dualistic, and thus reductivist, tendencies in other theoretical paradigms, social

scientists rarely apply this level of criticism to their own work. I am interested in what may happen

if, in taking 'the animal question' seriously, we seek to move away from this idea that human-animal

relationships (and the rest of social life) are neat and categorize-able and cease seeking 'the one'

theory which will explain it all. It is my contention that Sociology in its current forms can not contribute

effectively to the emancipation of animals in anything other than the most superficial of ways. This is due to

the fact that the vast majority of social thought is based in the very epistemological,

ontological (and methodological) systems that maintain the (anti-animal) status quo and thus

maintain the inferior status of animals in the first place. Indeed, it may even be argued that sociologists

inadvertently contribute to the maintenance of such oppression with their attachment to

theories and concepts which (often unintentionally) reinforce current oppressions. In order to

fully contribute to the emancipation of animals (and, for that matter, other oppressed groups),

sociologists must first address the very epistemic foundations of the discipline. This means re-

addressing social theory on the broadest of levels. This is not a new endeavor. It has been oft pointed out that

much Sociology is based upon essentialist and/or dualist thinking and that, in order to remain topical and

relevant to the changes in modern life, Sociology must abandon such modernist pretensions (e.g. Latour 1993).

Despite this, the history of Sociology is littered with failed attempts to move away from the structure-agency

divide and/or attempts to rethink this divide. Indeed some have argued that the social sciences "have alternated

between two types of equally power- ful dissatisfactions," those of micro and macro level theories (Latour

2004a. 16V This is evidenced in the numerous attempts within Sociology to either move beyond dualistic

modes of thought (e.g. Garfinkel 1967) or to re-unify the structure-agency divide (e.g. Giddens 1984). It is

worth noting here that such attempts to re-cast the structure- agency divide do so from within 'traditional'

Sociology with its 'mod- ernist' overtones. Traditional sociology, broadly conceived, is positivist in orientation

and as such operates under the assumption that there is a reality 'Out There' to be understood through the appli-

cation of various scientific methods to the problem at hand. As such, these theories begin from a structural

perspective which sees the structures or social forces in society as more powerful than those who inhabit them.

Arguably, this has little relevance to modern society with its unstructured and mobile character. That is to say

that there is increasing recognition that the hitherto assumed stability of society and the relationships within it

are now increasingly drawn into ques- tion. Gone are the ideas of the past where "'the social' was about

conformity; the rest was anomie, anomaly, pathology or deviance: the a-social, the anti-social" (Baurnan 2004,

21). Instead, in their place lie conceptions of society as liquid-modern,' as ultimately and irrevoca- bly mobile

and emergent, i.e. as constantly in a state of flux and change and as produced by its inhabitants as opposed to

being pre- existing. With this re-conceptualization of society as fluid, mobile, messy, and often un-

categorisable comes an emphasis on "the pro- cessuality of relationships" (Bauman 2004, 22). In other words

schol- ars are starting to abandon the idea of concrete relationships that have a pre-existing form and instead

see them as a processas always on the move, in flux and always under creation. Thus sociologists, now freed

from the limiting confines of studying only relationships, can begin instead to study their 'relating,' i.e. the

processes not the person (Latour 2004a, 20). Theoretically this allows a move away from the inherent

psychologism of Sociology and away from traditional, dualist accounts towards a "praxiological,

constructionist account" (Coulter 1989, 6). Crucially, for human-animal studies, this means that 'the social' is

no longer synonymous with 'the human.' To date, attempts to re-work social theory in such light have, how-

ever, failed and still return to either some form of essentialism or rest upon some kind of dualism(s) or, more

typically, both. After all, this way of knowing the social world is so deeply ingrained that it usually goes

unquestioned, even by sociologists. It is, however, this intellectual traditionof Cartesian dualistic

modes of thoughtwhich justifies many of the oppressions in our world today by creating

'Others' to whom we deny key things such as the right to be fully counted as a 'social being'

(for further discussion see Spiegel 1988). Thus it would seem logical to hypothesize that if such modes of

thought could be eradicated it may well lead to a concomitant eradication of the the forms of

oppression they so easily lead to and justify, chief amongst which is animal oppression.

Case

The Middle Passage did not uniquely privilege racism the affs starting point is both

historically incorrect and serves to justify the racism inherent in modernity and the

European Enlightenment

Gikandi 02 Simon, Currently Robert Hayden Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, he

is the recipient of awards from organizations such as the American Council of Learned Societies, the Mellon Foundation, and the Guggenheim

Foundation. His most recent books include Maps of Englishness: Writing Identity in the Culture of Colonialism and Ngugi Wa Thiong'O,

Available from Project MUSE, American Literary History, 14.3, pg. 604,

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_literary_history/v014/14.3gikandi.html, Race and Cosmopolitanism | ADM

Modernity has been a central category in Gilroy's work for a while now. As he sees it, the challenge of

blackness in the world today is how to come to terms with the economy of the modern. Many of the

arguments in Against Race are animated by Gilroy's conviction that whatever our origins and localities, we live under the

structure and sign of modernity. Our identity is premised on the teleology of modernity and its

promise of progress, human rights, and equality. At the same time, however, Gilroy is quick to

acknowledge that modernity is itself a sign of crisis, that it emerges from a regimen simultaneously defined by the

promise of right and reason and their failure. The most prominent sign of this failure, he argues, is race and

racialism. Some of the most poignant moments of Against Race are the ones in which Gilroy underlines how " modernity

transformed the ways 'race' was understood and acted upon" (57) or rehearses the long history in which the

central ideas of modernity were shaped and haunted by the reality of difference. This is a very important aspect of

Gilroy's book because it goes against the tendency, especially prevalent in American social theory, to

privilege race and racism as a peculiar and hence unique phenomenon of the New World, the

product of the experience of modern slavery. Against Race is an important book for students of

American culture precisely because of its European terms of reference, which enable the author to

trace the long hand of racialism to our western heritage, including our legacy of Enlightenment.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- SyllabusDocument2 pagesSyllabusDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Dummy PDFDocument1 pageDummy PDFDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Word PICs Bad UpdatedDocument7 pagesWord PICs Bad UpdatedDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Aff Uco FinalsasdfDocument15 pagesAff Uco FinalsasdfDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Wake Forest Athanasopoulos Dean Aff Harvard Round2Document7 pagesWake Forest Athanasopoulos Dean Aff Harvard Round2DwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- At Boehner DA AkashDocument2 pagesAt Boehner DA AkashDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Climate DealDocument1 pageClimate DealDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- A Thank You From 2 Mello + TracklistDocument1 pageA Thank You From 2 Mello + TracklistRutenbündelbälle McschmalzPas encore d'évaluation

- Carthage B - 1ACDocument10 pagesCarthage B - 1ACDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- CE Byrd Leverman Nabors Aff Ghill Round1Document10 pagesCE Byrd Leverman Nabors Aff Ghill Round1DwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- 2ac vs. SchopenhauerDocument14 pages2ac vs. SchopenhauerDwaynetheroc100% (1)

- Reps FirstDocument2 pagesReps FirstDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- A Door Into Ocean Negative - Wave 1 - HSS14Document55 pagesA Door Into Ocean Negative - Wave 1 - HSS14DwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Guest Workers Critical 1ncDocument18 pagesGuest Workers Critical 1ncDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Militarising Education for National SecurityDocument3 pagesMilitarising Education for National SecurityDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- DNG Aff 2acDocument15 pagesDNG Aff 2acDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Attorney Client LD TopicDocument122 pagesAttorney Client LD TopicDwaynetherocPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Grace Ogot - Green LeavesDocument3 pagesGrace Ogot - Green Leavessurbhi sabharwal79% (14)

- Police Report Writing Answer KeyDocument2 pagesPolice Report Writing Answer KeyJean Rafenski Reynolds100% (3)

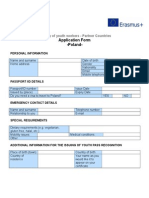

- Application Form PolandDocument4 pagesApplication Form PolanddeeavlasiePas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan The Happiest Boy in The WiorldDocument10 pagesLesson Plan The Happiest Boy in The WiorldHanah Abegail Navalta50% (6)

- Conversations With My Higher SelfDocument3 pagesConversations With My Higher SelfSchmolmuellerPas encore d'évaluation

- Policy BriefDocument38 pagesPolicy Briefsy4hinPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study Module Understanding Transport ChainDocument16 pagesCase Study Module Understanding Transport ChainWan Sek ChoonPas encore d'évaluation

- My Hero Dad's BraveryDocument8 pagesMy Hero Dad's BraveryGurdip KaurPas encore d'évaluation

- Counselor Brief StatementDocument3 pagesCounselor Brief Statementapi-251294159Pas encore d'évaluation

- Amber Black Resume 2019Document1 pageAmber Black Resume 2019api-461359632Pas encore d'évaluation

- CreativityDocument18 pagesCreativityVivek ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Story Rumble ProcessDocument2 pagesStory Rumble ProcessHeather TatPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Annotated BibliographyDocument7 pagesFinal Annotated Bibliographyapi-486295966Pas encore d'évaluation

- Modernization Theory and Dependency TheoryDocument3 pagesModernization Theory and Dependency Theorywatanglipu hadjar100% (4)

- A New Earth Essay: Understanding Tolle's InsightsDocument10 pagesA New Earth Essay: Understanding Tolle's InsightsRyan De la TorrePas encore d'évaluation

- Listening SkillDocument17 pagesListening SkillDanielle NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Aon Hewitt Model of EngagementDocument10 pagesAon Hewitt Model of Engagementgurbani100% (1)

- Sample Exemplar (Dummy Only)Document12 pagesSample Exemplar (Dummy Only)Arlyn TapisPas encore d'évaluation

- DiglossiaDocument5 pagesDiglossialksaaaaaaaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Expectancy Violations Theory - SimplifiedDocument3 pagesExpectancy Violations Theory - SimplifiedRajesh CheemalakondaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philo-Social Foundations of Education: Ornstein Levine Gutek VockeDocument25 pagesPhilo-Social Foundations of Education: Ornstein Levine Gutek VockeLeonard Finez100% (1)

- Madeline, A Picture Book Written and Illustrated by Ludwig Bemelmans in 1939 Is A Classic inDocument1 pageMadeline, A Picture Book Written and Illustrated by Ludwig Bemelmans in 1939 Is A Classic inElyssa Dahl0% (1)

- GETS 1 v3Document137 pagesGETS 1 v3Paul PastranaPas encore d'évaluation

- 12) "BLISS": Katherine MansfieldDocument7 pages12) "BLISS": Katherine MansfieldMariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nef Elem Filetest 04 AnswerkeyDocument6 pagesNef Elem Filetest 04 AnswerkeyoliverazristicPas encore d'évaluation

- Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (ACE-R) (1) - NewDocument13 pagesAddenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (ACE-R) (1) - NewEcaterina ChiriacPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 3 Practice ExamDocument3 pagesUnit 3 Practice ExamKaraLyn HatcherPas encore d'évaluation

- Flexible Working As An Employee Recruitment and Retention Tool in The Public Sector in Bosnia and HerzegovinaDocument7 pagesFlexible Working As An Employee Recruitment and Retention Tool in The Public Sector in Bosnia and HerzegovinaKhan Khan0% (2)

- White-Paper-Leadershi Blind Spot WP 050817Document7 pagesWhite-Paper-Leadershi Blind Spot WP 050817V MejicanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Deep Fakes (Final)Document7 pagesDeep Fakes (Final)Excel ChukwuPas encore d'évaluation