Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Transgender Men's Sexual Health and HIV Risk

Transféré par

Lukas Berredo0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

55 vues9 pagesWhat are transgender men’s sexual health and HIV prevention needs, based on a search of literature published since the beginning of 2004?

Titre original

Transgender Men’s Sexual Health and HIV Risk

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentWhat are transgender men’s sexual health and HIV prevention needs, based on a search of literature published since the beginning of 2004?

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

55 vues9 pagesTransgender Men's Sexual Health and HIV Risk

Transféré par

Lukas BerredoWhat are transgender men’s sexual health and HIV prevention needs, based on a search of literature published since the beginning of 2004?

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 9

Rapid Review #33: September 2010

Transgender Mens Sexual Health

and HIV Risk

Question

What are transgender mens sexual health and HIV prevention needs,

based on a search of literature published since the beginning of 2004?

Key Take-Home Messages

There is very little research about transmens sexual health, or their

rates of HIV and STI infection. Existing research involving relatively

small groups of transmen has found low rates of HIV infection. (4;6)

A systematic review of the HIV prevention needs of transgender

people, published in 2008, found five US studies that reported

information on rates of HIV among FTM (4):

Three studies in which participants self-reported their HIV status

found HIV prevalence of 0%.

One study where participants self-reported HIV status found HIV

prevalence of 3%.

In the only study where participants took antibody tests, the HIV

prevalence rate among study participants was 2%.

HIV risk among transmen is not well understood. A number sexual

behaviours and sex-related behaviours put transmen at risk of

becoming infected with, and transmitting, HIV and other STIs. An

important finding from two relatively small studies of transgender

people in the Philadelphia and Chicago regions was that transmen

were significantly more likely than transwomen to engage in risky

sexual behavior. (5;9)

Contextual factorsindividual, interpersonal, and structural/societal

factorsmay affect the sexual health and HIV risk of transmen. While

individual and interpersonal factors have been identified and

Ontario HIV Treatment Network ~ 1300 Yonge Street Suite 600 Toronto Ontario M4T 1X3

ph: 416 642 6486 | toll-free: 1-877 743 6486 | fax: 416 640 4245 | www.ohtn.on.ca | info@ohtn.on.ca

EVIDENCE INTO ACTION

The OHTN Rapid Response

Service offers HIV/AIDS programs

and services in Ontario quick

access to research evidence to

help inform decision making,

service delivery and advocacy.

In response to a question from

the field, the Rapid Response

Team reviews the scientific and

grey literature, consults with

experts, and prepares a brief fact

sheet summarizing the current

evidence and its implications for

policy and practice.

Suggested Citation:

OHTN Rapid Response Service. Rapid

Review: Transgender Mens Sexual

Health and HIV Risk. Ontario HIV

Treatment Network, Toronto, ON,

September,2010

Prepared by:

Glenn Betteridge

Michael G. Wilson, PhD

Program Leads / Editors:

Michael G. Wilson, PhD

Jean Bacon

Sean B. Rourke, PhD

Contact::

rapidresponse@ohtn.on.ca

discussed is the literature (1;4-10), virtually no research studies have

been conducted to better understand their impact on the HIV risk for

transmen.

We did not find any published evaluations of HIV prevention

interventions specific to transmen. One intervention used a pre-test

and two post-test questionnaires (without a control group) to evaluate

an intervention delivered to mixed groups of transgender men and

women. The intervention appeared effective in improving participants

attitudes toward condom use, safer sex self-efficacy and in reducing

sexual risk behaviours. (11)

Numerous researchers, health care providers, academics, and

community members call for more research into the lives and sexual

health and HIV prevention needs of transgender people, or

specifically of transmen. (1;4-6;9;11-14)

The Issue and Why Its Important

In order to develop evidence-informed programs and interventions that promote

healthful sexual lives among transmen in Ontario, it is important to understand

the ways in which transmen may be at risk for sexually transmitted infections

(STIs), including HIV. It is also important to understand the ways in which the

strengths, social structures, and resources within transmen communities can

play a role in protecting and promoting their sexual health.

There is very little published research evidence about the sexual health and HIV

prevention needs of transmen, in Ontario or elsewhere. And there is very little

research evidence documenting HIV rates among transmen. In contrast, there

is considerably more research on HIV risk among and the HIV prevention needs

of transwomen (MTF). That research indicates that there are numerous

biological/physiological, behavioural, social and economic factors that have

placed certain groups of transwomen at extremely high risk of HIV.(4)

While significant differences exist between transwomen and transmen and their

communities, there are important similarities that beg us to ask whether

transmen are also at elevated risk for acquiring STIs, including HIV. Both

transwomen and transmen: 1) face social exclusion and marginalization due to

the fact that often society and social instructions are hostile to people who do

not conform to binary gender categorization (i.e., male vs. female); 2) choose

medical and non-medical ways to change their bodies or physical appearance to

make them more closely fit their gender identity; and 3) identify with a range of

sexual orientations and engage in an array of sexual behaviours, in a range of

circumstances, with people of varying genders and sexual orientations (5).

These three factors may influence the sexual health and well-being of transmen,

including the risk that some transmen may acquire STIs / HIV infection.

Transmens unique experiences and bodies may also influence their sexual

healthfulness and HIV risk.

What We Found

To determine the HIV prevention and sexual health needs of transmen, it is

important to identify and understand how specific behaviours and underlying

factors influence the sexual health and HIV risk of transmen. Peer reviewed

research studies and commentary by experts in the field (both academic and

community) provide evidence to inform our understanding.

In our search we found numerous articles that reported on sexual health, HIV

prevalence and HIV risk among transgender people but data for transmen and

transwomen were not reported separately. For example, a review article

includes data from studies involving 207 transgender people (15) and a needs

assessment of transgender people in Boston (10) do not provide data

separately for transmen and transwomen.

Rates of STIs and HIV among Transmen

Historically, the common assumption in the academic and peer-reviewed

literature was that transmen were not at risk of becoming infected with HIV, and

certainly not at risk to the same extent as transwomen (3;5), because transmen

are often assumed to be primarily having sex with nontranswomen (5). Perhaps

as a corollary to this, there is very little research about HIV rates among

transmen with no published research studies or estimates of the rates of HIV

among transmen in Canada (at least based on our searches), and only a small

number of studies involving small groups of transmen in various locations in the

USA.

A systematic review of the HIV prevention needs of transgender people,

published in 2008, found five US studies that reported information on rates of

HIV among FTM (4):

Three studies in which participants self-reported their HIV status found HIV

prevalence of 0%.

One study where participants self-reported HIV status found HIV prevalence

of 3%.

In the only study where participants took antibody tests, the HIV prevalence

rate among study participants was 2%.

In addition, the 2008 systematic review reported low rates of self-reported STI

diagnosis in two studies in which minority transmen were the majority of study

participants (6% in one study; and 7% in the other study) .(4) Furthermore, in

one recent study, one out of 45 transmen reported being HIV-positive (2.2%). (6)

In the same study, nearly 47% of study participants reported that they had been

diagnosed with an STI during their lifetime.

Transmens HIV risk

HIV risk among transmen is not well understood. (5) Recently some researchers

and other authors have begun to question the assumption that transmen were

at low risk for HIV infection, and some have conducted research on their HIV risk

behaviours. One systematic review (4) and a small number of needs

assessment studies (2;5;9;16) of transgender people in the USA describe or

suggest sexual and other risk behaviours, as well as contextual factors, that put

transmen at risk of HIV infection. These HIV risk factors may also place

transmen at risk of other STIs.

A Note on Language:

The language used to describe

transgender identity is con-

stantly evolving. (2) We use the

term transmen to refer to peo-

ple who were assigned female

at birth and who have a male

gender identity or masculine

gender expression. This use of

language is consistent with re-

cent publications developed by a

community-based researcher

and members of the transmens

community. (1;3) We also use

the terms FTM and MTF

where warranted to accurately

convey the methodology, results

and discussion from a published

research study.

In general, the literature we reviewed identifies a number sexual behaviours and

sex-related behaviours that put transmen at risk of becoming infected with, and

transmitting, HIV:

unprotected sex, including unprotected anal intercourse, unprotected

vaginal (front hole) intercourse, and unprotected oral intercourse (2;4;5;9)

sex while under the influence of alcohol and other drugs (4;6)

engaging in commercial sex work (4)

sex with populations who have high rates of HIV infection, including MSM,

gay men, and trans women (4)

Unprotected anal intercourse and vaginal (referred to by some transmen as

frontal or front hole sex (3;6)) are understood as a high risk activities for HIV

transmission among transmen. However, only three research studies

distinguished between unprotected anal/vaginal/frontal intercourse versus

unprotected oral sex:

Washington, DC (17): Within a group of 60 African American transmen

(termed natal females in this study):

67% reported unprotected genital-genital contact in their lifetime,

22% reported unprotected genital-genital contact in the last month.

15% reported unprotected genital-anal contact in their lifetime, and

3% reported unprotected genital-anal contact in the last month.

None reported ever having engaged in unprotected sex with a known

HIV-positive partner.

Across the USA (6): Questions about vaginal (frontal) sex, anal sex and

condom use for these activities were asked of a group of 45 predominantly

White transmen from across the USA who have sex with non-transmen

(trans MSM).

Approximately 82% reported ever having vaginal (front) sex; 69% in

the past year.

Among people who reported vaginal (front) sex, 33.3% reported that

they never used a condom or only used a condom about half the

time or less.

Approximately 71% reported ever having anal sex with 60% reporting

engaging in anal sex in the past year.

Among people who reported anal sex, 17.7% reported that they

never used a comdom or only used a condom about half the time or

less.

As part of an evaluation of an intervention to reduce HIV and STI risk in the

transgender community, 181 transgender people (141 MTF; 34 MTF) answered

questions about their sexual behaviour. (11) However, the reported results do

not distinguish between the two groups of people.

Sharing of injecting drug equipment, including for the injection of hormones or

silicone, is also a high risk activity for HIV transmission. In the studies that

examined this issue with transmen, rates of lifetime needle sharing were low:

3% shared unclean needles (17); 0% needle-sharing for hormone use.(6) One

study of 181 transmen and transwomen reported no needle sharing.(11)

An important finding from two relatively small studies of transgender people in

the Philadelphia and Chicago regions was that transmen were significantly more

likely than transwomen to engage in risky sexual behavior. (5;9) Transmen were

less likely than transwomen to have used protection the last time they had sex

(5), and significantly more likely to have engaged in high risk sexual activities in

the three months prior to being interviewed for the study (5;9). When the

Chicago study participants were asked about their future sexual behaviours,

transmen were more likely than transwomen to engage in unprotected sex, non-

monogamous sex, sex while drunk or high, and sex with an HIV-positive person.

(9)

Transmen identify with a range of sexual orientations.(6;16) One study found

that transmen were significantly more likely that transwomen to identify their

sexual orientation as homosexual.(16) However, sexual orientation and

homosexual were not defined for study participants. In the study, of the 27

homosexual identified FTMs, 28% reported oral-penis sex; 42% reported vagina-

penis sex; 42% reported anal-penis sex; 71% reported oral-vagina sex; 88%

reported oral-vagina sex; and 88% reported vagina-vagina sex. (16) This

evidence suggests that transmen have sex with MSM and/or gay men, groups

with historically high rates of HIV in the USA and Canada.

Numerous contextual factors (i.e., individual, interpersonal, and structural/

societal factors) that may be detrimental to transgender peoples health and

sexual health have also been noted in the literature. These contextual factors

have largely been discussed with respect to both transmen and transwomen.

Individual Factors

mental health issues and impact of psycho-social stresses (8),

including suicidal thoughts(4), and anxiety and depression (7)

misperceptions or a low perceived risk of HIV (4;5;9)

low self-esteem (1;5), internalized stigma and shame (7)

fear of rejection by prospective sexual partners and perceived

shortage of sexual partners (7)

seeking self-affirmation and validation of gender identity through sex

with desired partners (6;7)

physiological and/or sex-drive changes associated with hormone

use and surgeries (1;5;8)

Interpersonal Factors

physical and sexual abuse and violence at home (4)

complicated gender and power dynamics in relationship with non-

transmen (1;6)

difficulties associated with disclosure of trans identity to, and

discussing their bodies and sex with, prospective sexual partners,

including inadequate language to communicate these issues (6;10)

and the need among transgender people for physical, emotional,

and sexual safety (12)

partners resistance to condom use (6)

Structural/Societal Factors

narrowly constructed gender norms (9) and societal oppression of

gender non-conformity (7)

barriers to employment, social services, housing, legal assistance

(4) and health and mental health care (2;4)

These factors have been identified and discussed is the literature. Yet, virtually

no evaluations have been conducted to assess their impact on the HIV risk and

sexual health of transmen. In addition, the research does not provide insight

into how prevalent these factors are or how they interact with one another. As a

result, there is virtually no published research evidence about the effect of

individual and interpersonal factors on transmens sexual decision-making,

sexual behaviour and sexual health outcomes.

In one recent research study about interpersonal contextual factors, the

relationship between interpersonal communication skills, sexual

communication, and sexual health among 41 transgender people was

examined. (12) The study found that transgender people held multiple, often

competing goals in safer sex conversations as a means for negotiating

emotional, physical, and sexual health in relationships. The authors also note

that risk to sexual health might arise in situations where guarding against

threats to physical and emotional safety and, as a result, sexual health

strategies that stress condom use or sexual history discussion may

inadvertently place transgender individuals at risk of physical or emotional

harm.

In contrast to the lack of research on individual and interpersonal factors,

access and barriers to health care for transgender people (a structural/societal

factor) has been researched in more depth. This research has examined

barriers including attitudes, perceptions, and denial of health care and other

discriminatory behaviours by health care providers and other staff.(2;10) Being

transgender may also present a larger barrier for transmen as compared to

transwomen when attempting to access primary health care. For instance, two

studies found that more transmen than transwomen faced barriers for physical

exams. (9;11;18) These barriers are likely attributed to the fact that some

medical procedures are associated with female anatomy (e.g., pap smear) and

are routinely included in such exams and that some transman may struggle

psychically with the female manifestations of their bodies.

Sexual health and HIV prevention needs of transmen

A small number of needs assessments, conducted among transmen in the USA,

report on and discuss the health and social service, sexual health and HIV

prevention needs of transgender people, including transmen.(2;5;9;16) Many

of these needs flow out of the individual, interpersonal and structural/societal

factors that impact the lives of transgender people (listed in the previous

section of this document). In addition, numerous articles discuss the health and

sexual health needs of transgender people, but do not report original research

study results. Finally, the discussion section of one research article identifies

the specific sexual health and HIV prevention needs of transmen who have sex

with non-transmen (trans MSM).(6)

This literature identifies, the health, sexual health, and HIV prevention

challenges and needs of transgender people (and in some cases transmen,

where specified):

greater visibility and affirmation of transgender identity (7)

lack of language to talk about transgendered bodies (12)

access to trans-knowledgeable and appropriately trained service providers

(5;6;8;10;18-21), which could include:

improved history-taking, interviewing and data collection by health

care providers, including training on how to use and interpret forms

(authors refer to policy recommendations and training from the

Center for Excellence on Transgender HIV Prevention (6;19) and the

California STD/HIV Prevention Training Center (4;19)

health care practice should follow recognized standards of care for

transgender people, health care providers and staff should seek out

training, and physical spaces should be made more accessible to

transgender people (authors refer to standards developed by the

World Professional Association for Transgendered Health

(8;18;19;21), the Tom Waddell Health Center (18-20), and the

Transgender Training Project of the New England AIDS Education

and Training Center(4;8;18;20)

lack of knowledge among gynecologists of the special needs of

transgender people (22)

involving transgender people in training health care providers and

staff (20)

basic HIV prevention education for transmen and their sexual partners (5;6)

sexual health resources and services for non-trans MSM must be fully

accessible to trans MSM (6)

the unique needs of transgender experience, identity and bodies, sexuality,

and sexual safety (which are distinct from male or female sexuality) should

be addressed in sex health promotion interventions (7;12)

sexual risk reduction efforts need to take into account the multiple

meanings of sexual safety (12)

provide opportunities to develop and practice strategies for discussing and

negotiating sexual safety (12)

One evaluation of an intervention to reduce HIV and STI risk among transgender

people collected information on transgender mens and trangender womens

sexual health behaviours, challenges and needs.(11) These included:

trouble getting aroused (38%)

low sexual desire (34%)

difficulty reaching orgasm with a partner (28%)

not informing primary health care provider of trans identity (48%)

concealing their sexual identity from others (64%)

discrimination as a result of gender identity of presentation (66%)

Sexual health, HIV prevention programs and interventions for transmen

We did not find any published evaluations of HIV prevention interventions

specific to transmen.

One evaluation of an intervention to reduce HIV and STI risk among trangender

people was published in 2005.(11) The intervention (All Gender Health)

consisted of a two-day seminar in community-based venues and included

lectures, panel discussions, videos, music, exercises and small group

discussions. The intervention was delivered to 235 tansgender people, and

181 (141 MTF; 34 MTF) completed the evaluation. The evaluation involved pre-

test, post-test and three-month follow-up questions about attitudes, self-

efficacy, and behaviours. The vast majority (93%) of people who participated

in evaluation identified as White, and 73% had completed at least some

college education. The study provided three key findings:

The intervention appeared effective in improving participants attitudes

toward condom use and safer sex self-efficacy, and in reducing their

sexual risk behaviours (i.e., unprotected anal or vaginal sex outside of a

primary, monogamous relationship decreased from 16% at pre-test to 9%

at follow-up).

An improvement in safer sex self-efficacy was observed between pre- and

post-test measures but this was not sustained at the three-month follow-

up. While the seminar provided a tremendous boost to participants self-

esteem and self-confidence, participants struggled to hold on to these

gains in their daily lives.

Transmen were significantly more likely than transwomen to drop out of

the two-day intervention and not complete the post-intervention

questionnaire. As a result of the challenges encountered with attracting

and retaining transmen in the study, the authors suggest that transmen

might be better targeted with a separate intervention.

In addition, participants in another study of trans MSM reported high levels of

internet use. This raises the potential for using the internet to disseminate

accurate sexual health info among transmen and their non-transgender

sexual partners, and to raise awareness about transmen in the gay male

communities. (6)

Research is needed

The extent to which transmen (and transwomen to a lesser extent) have been

left out of sexual health and HIV prevention research and interventions is

poignantly illustrated by the fact that the most recent US Centers for Disease

Control Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Prevention Interventions (August

2009) does not include any best- or promising-evidence interventions for

transgender people. Moreover, neither the CDC (7;20)nor the Public Health

Agency of Canada includes transgender as a category for the collection and

reporting of HIV surveillance data. A model for more complete data collection

does existsince 2002 MTF and FTM have been gender reporting options

in publicly funded HIV testing and counseling sites in California.(13)

In the literature we reviewed, numerous researchers, health care providers,

academics and community members call for more research into the lives and

sexual health and HIV prevention needs of transgender people and specifically

of transmen. Specific recommendations include:

Working collaboratively with transmen to conduct research. (5)

Involving larger and more diverse samples of trans MSM, including trans

MSM of colour and harder to reach people. (6)

Conducting more research among transgender children and adolescents.

(14)

Engaging in more inclusive data collection methods to better capture

subgroups of transgender people. (1)

Engaging in qualitative research to inform the development and design of

References

1. Sevelius, J, Schiem, A, and Giam-

brone, B. What are transgender

men's HIV prevention needs? San

Francisco, CA: University of Califor-

nia San Fancisco, Centre for AIDS

Prevention Studies, Technology and

Information Exchange Core; 2010.

Report No.: Fact Sheet 67.

2. Kenagy GP. Transgender health:

Findings from two needs assess-

ment studies in Philadelphia.

Health & Social Work 2005;30

(1):19-26.

3. Gay Mens Sexual Helath Alliance.

Primed: The Back Pocket Guide for

Transmen and Men Who Dig Them.

Toronto, Canada: Gay Mens Sexual

Helath Alliance; 2010.

4. Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ,

McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz

N. Estimating HIV prevalence and

risk behaviors of transgender per-

sons in the United States: A sys-

tematic review. AIDS and Behavior

2008;12(1):1-17.

5. Kenagy GP, Hsieh C-M, Kennedy G.

The risk less known: Female-to-

male transgender persons' vulner-

ability to HIV infection. AIDS Care

2005;17(2):195-207.

6. Sevelius J. "There's no pamphlet for

the kind of sex I have": HIV-related

risk factors and protective behav-

iors among transgender men who

have sex with nontransgender

men. Journal of the Association of

Nurses in AIDS Care 2009;20

(5):398-410.

7. Bockting WO. Transgender identity

and HIV: Resilience in the face of

stigma. Focus: A Guide to AIDS

Research 2008;23(2):1-4.

8. Feldman JL, Goldberg JM. Trans-

gender primary medical care. Inter-

national Journal of Transgenderism

2006;9(3-4):3-34.

9. Kenagy GP, Bostwick WB. Health

and social service needs of trans-

gender people in Chicago. Interna-

tional Journal of Transgenderism

2005;8(2-3):57-66.

10. Sperber J, Landers S, Lawrence S.

Access to health care for transgen-

dered persons: Results of a needs

assessment in Boston. Interna-

tional Journal of Transgenderism

2005;8(2-3):75-91.

11. Bockting WO, Robinson BE, Forberg

J, Scheltema K. Evaluation of a

sexual health approach to reducing

HIV/STD risk in the transgender

community. AIDS Care 2005;17

(3):289-303.

12. Kosenko KA. Meanings and dilem-

mas of sexual safety and communi-

cation for transgender individuals.

Health Communication 2009;25

(2):131-41.

quantitative instruments to increase their relevance to the lives of

transgender people (5)

Exploring transgender peoples perceptions of their own gender identity,

bodies and sexual orientation, the range of sexual behaviours in which they

engage, and the types of physical and psychological transitions they

undergo. (5;9)

Further exploring the HIV risk factors for transmen (types of sex partners,

level of participation in commercial sex work, frequency of sharing drug and

hormone injecting equipment). (4)

Examining the effect of hormone treatment on sexual behavior patterns. (4)

Disentangling and identifying the nature of the complex relationship

between HIV risk behaviours and contextual factors.(4;13)

Identifying types of social supports and characteristics of relationships that

are most likely to produce an environment that fosters reduced risk

behaviours. (4;12)

Examine how to sustain over time the immediate positive impacts observed

in one sexual health promotion program of transgender people. (11)

Factors that May Affect Local Applicability

Existing research about risk factors and the prevalence of HIV among transmen

should be viewed with caution for a number of reasons. First, there are only a

small number of studies and those studies are limited in terms of sample size.

Second, study participants were selected in ways that did not limit selection

biases. Third, sexual risk behaviours were not defined consistently across the

various studies. Finally, the study designs do not permit study findings to be

extended beyond the group of transmen who participated in a particular study.

Further, all of the existing research we found involved transmen in the USA.

Given that the HIV epidemic in the USA is roughly comparable to that in Canada,

the research questions and methodologies (and challenges identified by those

who conducted the research) may have potential to be adapted to the Canadian

context.

What We Did

To identify any systematic reviews we hand searched the Cochrane HIV/AIDS

review group. In addition, we searched the Cochrane Library, Health-

Evidence.ca and DARE by entering transgender as a search term. Next, we

searched Medline and Embase using the following combination of search terms:

(Transvestism [MeSH] OR Transsexualism [MeSH] or transgender [text term])

AND (HIV or sexual health (text terms)). We searched CINAHL using a

combination of text terms (transgender AND [HIV or sexual health]). All

databases were searched from 2004 to 6 July 2010.

13. San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

HIV Evidence Report: Transgender

Persons and HIV. San Francisco,

CA: San Francisco AIDS Founda-

tion; 2009.

14. Stieglitz KA. Development, risk, and

resilience of transgender youth.

Journal of the Association of

Nurses in AIDS Care 2010;21

(3):192-206.

15. Bockting W, Huang C-Y, Ding H,

Robinson B, Rosser BRS. Are trans-

gender persons at higher risk for

HIV than other sexual minorities? A

comparison of HIV prevalence and

risks. International Journal of

Transgenderism 2005;8(2-3):123-

31.

16. Kenagy GP. The health and social

service needs of transgender peo-

ple in Philadelphia. International

Journal of Transgenderism 2005;8

(2-3):49-56.

17. Xavier JM, Bobbin M, Singer B,

Budd E. A needs assessment of

transgendered people of color

living in Washington, DC. Interna-

tional Journal of Transgenderism

2005;8(2-3):31-47.

18. Dutton L, Koenig K, Fennie K. Gyne-

cologic Care of the Female-to-Male

Transgender Man. Journal of Mid-

wifery and Women's Health

2008;53(4):331-7.

19. Keller K. Transgender health and

HIV. Bulletin of Experimental Treat-

ments for AIDS 2009;21(4):40-50.

20. Lurie S. Identifying training needs

of health-care providers related to

treatment and care of transgen-

dered patients: A qualitative needs

assessment conducted in New

England. International Journal of

Transgenderism 2005;8(2-3):93-

112.

21. Phillips JC, Patsdaughter CA. Tran-

sitioning into competent health and

HIV care for transgender persons.

Journal of the Association of

Nurses in AIDS Care 1920;(5):335-

8.

22. van Trotsenburg MAA. Gynecologi-

cal aspects of transgender health-

care. International Journal of Trans-

genderism 2009;11(4):238-46.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Research For Sex Work 15Document40 pagesResearch For Sex Work 15Lukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Trans Health and Human RightsDocument36 pagesTrans Health and Human RightsDhanzz JiePas encore d'évaluation

- Community Guide: Young Sex WorkersDocument5 pagesCommunity Guide: Young Sex WorkersLukas Berredo100% (1)

- Policy Brief: Young Sex WorkersDocument14 pagesPolicy Brief: Young Sex WorkersLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Teacher's Guide To Inclusive EducationDocument28 pagesTeacher's Guide To Inclusive EducationLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Including Non-Binary People: Guidance For Service Providers and EmployersDocument36 pagesIncluding Non-Binary People: Guidance For Service Providers and EmployersLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Intersectionality ToolkitDocument24 pagesIntersectionality ToolkitLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Norm Criticism ToolkitDocument68 pagesNorm Criticism ToolkitLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights and Gender IdentityDocument52 pagesHuman Rights and Gender IdentityTRANScending BordersPas encore d'évaluation

- The Report of The 2015 U.S. Transgender SurveyDocument302 pagesThe Report of The 2015 U.S. Transgender SurveyLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Counting Trans People inDocument32 pagesCounting Trans People inLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Non-Binary People's Experiences of Using UK Gender Identity ClinicsDocument32 pagesNon-Binary People's Experiences of Using UK Gender Identity ClinicsLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Report On The Mental Health of LGBT People in ChinaDocument64 pagesReport On The Mental Health of LGBT People in ChinaLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Non-Binary People's Experiences in The UKDocument96 pagesNon-Binary People's Experiences in The UKLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Impunity and Violence Against Transgender Women Human Rights Defenders in Latin AmericaDocument44 pagesImpunity and Violence Against Transgender Women Human Rights Defenders in Latin AmericaTRANScending BordersPas encore d'évaluation

- Creating Inclusive Workplaces For LGBT Employees in ChinaDocument60 pagesCreating Inclusive Workplaces For LGBT Employees in ChinaLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Survey of The Living Conditions of Transgender Female Sex Workers in Beijing and Shanghai PDFDocument79 pagesA Survey of The Living Conditions of Transgender Female Sex Workers in Beijing and Shanghai PDFLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Omg I'm TransDocument40 pagesOmg I'm TransLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- An Activist's Guide To The Yogyakarta PrinciplesDocument75 pagesAn Activist's Guide To The Yogyakarta PrinciplesLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Report of The Online Survey On Homophobic and Transphobic BullyingDocument23 pagesReport of The Online Survey On Homophobic and Transphobic BullyingTRANScending BordersPas encore d'évaluation

- The State of Trans and Intersex OrganizingDocument36 pagesThe State of Trans and Intersex OrganizingTRANScending BordersPas encore d'évaluation

- Being LGBT in Asia: China Country Report (English)Document60 pagesBeing LGBT in Asia: China Country Report (English)Lukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- On The TeamDocument57 pagesOn The TeamTRANScending BordersPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights Report - UkraineDocument56 pagesHuman Rights Report - UkraineLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Needs and Rights of Trans Sex WorkersDocument14 pagesThe Needs and Rights of Trans Sex WorkersLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Affirmative Care For Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming PeopleDocument14 pagesAffirmative Care For Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming PeopleLukas Berredo100% (1)

- Trans Legal Mapping Report: Recognition Before The Law (English)Document69 pagesTrans Legal Mapping Report: Recognition Before The Law (English)Lukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Blueprint For The Provision of Comprehensive Care For Trans Persons and Their Communities in The Caribbean and Other Anglophone CountriesDocument88 pagesBlueprint For The Provision of Comprehensive Care For Trans Persons and Their Communities in The Caribbean and Other Anglophone CountriesTRANScending BordersPas encore d'évaluation

- Implementing Comprehensive HIV and STI Programmes With Transgender PeopleDocument212 pagesImplementing Comprehensive HIV and STI Programmes With Transgender PeopleLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- Asia and The Pacific Trans Health BlueprintDocument172 pagesAsia and The Pacific Trans Health BlueprintLukas BerredoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Pigeon Disease - The Eight Most Common Health Problems in PigeonsDocument2 pagesPigeon Disease - The Eight Most Common Health Problems in Pigeonscc_lawrence100% (1)

- TraceGains Inspection Day FDA Audit ChecklistDocument2 pagesTraceGains Inspection Day FDA Audit Checklistdrs_mdu48Pas encore d'évaluation

- Goals in LifeDocument4 pagesGoals in LifeNessa Layos MorilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Nitric AcidDocument7 pagesNitric AcidKuldeep BhattPas encore d'évaluation

- Pay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountDocument1 pagePay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountVee-kay Vicky KatekaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Bhert - EoDocument2 pagesBhert - EoRose Mae LambanecioPas encore d'évaluation

- Flusarc 36: Gas-Insulated SwitchgearDocument76 pagesFlusarc 36: Gas-Insulated SwitchgearJoey Real CabalidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca FinalDocument91 pagesKeratoconjunctivitis Sicca FinalJanki GajjarPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Do Banana Milk - Google Search PDFDocument1 pageHow To Do Banana Milk - Google Search PDFyeetyourassouttamawayPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaction Paper-RprDocument6 pagesReaction Paper-Rprapi-543457981Pas encore d'évaluation

- 6 Kuliah Liver CirrhosisDocument55 pages6 Kuliah Liver CirrhosisAnonymous vUEDx8100% (1)

- VPD RashchrtDocument2 pagesVPD RashchrtMarco Ramos JacobPas encore d'évaluation

- NORSOK M-630 Edition 6 Draft For HearingDocument146 pagesNORSOK M-630 Edition 6 Draft For Hearingcaod1712100% (1)

- Enviroline 2405: Hybrid EpoxyDocument4 pagesEnviroline 2405: Hybrid EpoxyMuthuKumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Feeder BrochureDocument12 pagesFeeder BrochureThupten Gedun Kelvin OngPas encore d'évaluation

- Discharge PlanDocument3 pagesDischarge PlanBALOGO TRISHA MARIEPas encore d'évaluation

- E61 DiagramDocument79 pagesE61 Diagramthanes1027Pas encore d'évaluation

- Soil SSCDocument11 pagesSoil SSCvkjha623477Pas encore d'évaluation

- Business Plan Example - Little LearnerDocument26 pagesBusiness Plan Example - Little LearnerCourtney mcintosh100% (1)

- Review - Practical Accounting 1Document2 pagesReview - Practical Accounting 1Kath LeynesPas encore d'évaluation

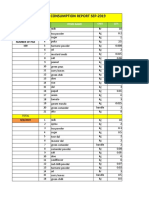

- Daily Staff Food Consumption Reports Sep-2019Document4 pagesDaily Staff Food Consumption Reports Sep-2019Manjit RawatPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample SWMSDocument4 pagesSample SWMSJuma KavesuPas encore d'évaluation

- EIL Document On Motor, PanelDocument62 pagesEIL Document On Motor, PanelArindam Samanta100% (1)

- Classification of Speech ActDocument1 pageClassification of Speech ActDarwin SawalPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Practice 6Document5 pagesReading Practice 6Âu DươngPas encore d'évaluation

- PPR Soft Copy Ayurvedic OkDocument168 pagesPPR Soft Copy Ayurvedic OkKetan KathanePas encore d'évaluation

- انظمة انذار الحريقDocument78 pagesانظمة انذار الحريقAhmed AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Alugbati Plant Pigment Extraction As Natural Watercolor SourceDocument6 pagesAlugbati Plant Pigment Extraction As Natural Watercolor SourceMike Arvin Serrano100% (1)

- Mainstreaming Gad Budget in The SDPDocument14 pagesMainstreaming Gad Budget in The SDPprecillaugartehalagoPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychoanalysis AND History: Freud: Dreaming, Creativity and TherapyDocument2 pagesPsychoanalysis AND History: Freud: Dreaming, Creativity and TherapyJuan David Millán MendozaPas encore d'évaluation