Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Good Bird Magazine Vol3 Issue1

Transféré par

mbee3Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Good Bird Magazine Vol3 Issue1

Transféré par

mbee3Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Good Bird

magazine!

Volume 3-1 Spring 2007

www.goodbirdinc.com

Empower the Human/Ani mal Bond wi th Posi ti ve Rei nforcement

The ABCs of Behavior

Bite Me!

If Horses Had Wings

Ex cues Me? You Want

me to do What?

Training your Parrot

to Talk on Cue

Flighted Parrots

in the Home

Scientific Studies and

Feather Picking

Foraging: An Integral

Component of

Enrichment

The ABCs of Behavior

Bite Me!

If Horses Had Wings

Ex cues Me? You Want

me to do What?

Training your Parrot

to Talk on Cue

Flighted Parrots

in the Home

Scientific Studies and

Feather Picking

Foraging: An Integral

Component of

Enrichment

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 3

Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich

4 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

Photo credit: Roelant Jonker/ Grace Innemee www.CityParrots.org

FROM THE EDITORS PERCH

Food for Thought

By Barbara Heidenreich . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT FOR GOOD BIRD . . . . . . .10

FEATURE ARTICLES

The ABCs of Behavior

By Susan G. Friedman, PhD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

ENRICHMENT (PART TWO)

Foraging Opportunity: An Integral Component of

Environmental Enrichment

By Jim McKendry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Bite Me!

By Gay Noeth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

If Horses Had Wings

By Cheryl Ward . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .79

Ex cues Me? You Want me to do What?

By Barbara Heidenreich . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .71

REGULAR FEATURES

PROFILE OF AN ANIMAL LOVERHELEN DISHAW . . . .54

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

HOW DID THEY TRAIN THAT? EXPERTS SHARE THEIR

TRAINING STRATEGIES

Training your Parrot to Talk on Cue

By Barbara Heidenreich . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .38

WHAT IS YOUR BIRD SAYING?

LEARN TO READ BIRD BODY LANGUAGE . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

LEARNING TO FLY

Flighted Parrots in the Home

By Barbara Heidenreich . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30

SCIENCE FOR THE BIRD BRAIN

(A Synopsis of Scientific Papers)

The Avian Brain and Intelligence (Part Two)

By Diane Starnes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .45

PICKIN PARROTS

Scientific Studies and Feather Picking

By Natasha Laity Snyder . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .41

YOUR GOOD BIRD! READER SUCCESS STORIES

Eclectus Parrots and Diet

By Andrea Frederick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56

Severely in Need of Patience

By Kimberly Sturman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57

Getting Closer to Nature

By Maria Isabel Sampaio . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

OUT OF THE MOUTHS OF PARROTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27

CONFERENCE, EVENT REVIEWS AND PRESS

RELEASES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .60

UPCOMING EVENTS AND SEMINARS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .65

QUOTH THE RAVENER, WE MEAN PARROT! . . . . . . . .22

Table of Contents

Good Bird

magazine!

Empowering the human-animal bond with positive reinforcement

Volume 3-1

Spring 2007

Publisher:

Good Bird Inc.

Editorial Director:

Barbara Heidenreich

Contributors:

Georgi Abbot

Helen Dishaw

Andrea Frederick

Susan Friedman, PhD

Barbara Heidenreich

Natasha Laity Snyder

Jim McKendry

Gay Noeth

Maria Isabel Sampaio

Diane Starnes

Kimberly Sturman

Cheryl Ward

Art Direction:

Persidea, Inc.

Advertising Offices:

Persidea, Inc.

7600 Burnet Road, Suite 300

Austin, TX 78757 USA

Phone: 512-472-3636

Email: goodbird@persidea.com

Photography:

Georgi Abbott

Arlene Alpar

Helen Dishaw

Matt Edmonds

Kate Friedman

Jon Guenther

Barbara Heidenreich

Grace Innemee

Roelant Jonker

Jim McKendry

Karen Povey

Sam Sharnik

Cheryl Ward

Web Design:

King Ink Studios

www.KingInkStudios.com

Trademark: Good Bird

is a registered trademark of

Good Bird Inc. It and other trademarks in this publica-

tion are the property of their holders.

Copyright: Good Bird

Magazine may not be repro-

duced in whole or in part in any form by any means of

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or

recording, by any information storage and retrieval

system now known or hereafter invented without the

express written permission from Good Bird Inc.

Reproduction or use in whole or in part of the con-

tents of this magazine is prohibited.

Disclaimer: Good Bird Inc. does not necessarily

endorse or assume liability for any of the advertisers,

products or services listed in this publication. Good

Bird

Magazine is an entertainment and information

resource on positive reinforcement training. Good Bird

Inc. does not accept responsibility for any loss, injury,

or inconvenience sustained by anyone using this pub-

lication.

For subscriptions, submissions or letters to the editor

please contact us at:

Good Bird Inc.

P.O. Box 684394

Austin, TX 78768

Phone: 512-423-7734

Email: info@goodbirdinc.com

www.goodbirdinc.com

Good Bird

Magazine is the ultimate resource for com-

panion parrot owners seeking information on positive

reinforcement training. Good Bird Magazine is pub-

lished quarterly (four times per year) by Good Bird

Inc.; PO Box 684394; Austin, TX 78768 USA.

Subscription Rate: Standard print subscriptions for US

addresses are $19.00. To subscribe or for other sub-

scription options, please visit our website at

www.goodbirdinc.com. Postmaster: Send address

changes to Good Bird Inc.; PO Box 684394; Austin, TX

78768 USA. Customer Service: For change of address,

please contact Good Bird Inc. at

info@goodbirdinc.com. For other customer service

issues please email info@goodbirdinc.com Back issues:

Previously published issues may be ordered at

www.goodbirdinc.com when available.

Front Cover: African grey parrot photographed by Helen

Dishaw.

Back Cover: Feral nanday conures in Florida photographed

by Matt Edmonds. To purchase photographs by Matt visit

www.mewondersofnature.com

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 9

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

T

he topic of using food as a

reinforcer for training seems

to be a hot topic these days.

Back in the very first issue of Good

Bird Magazine I addressed this in

the article titled Food, Glorious

Food. Using Food to Train.

However our subscribership has

grown since then and I imagine not

everyone has this issue in their col-

lection. In addition we have been

sold out of this issue for some time.

Insert obnoxious beeping noise here

becauseit is time for a special bul-

letin. Back issues of Good Bird

Magazine are now available for download! That is right.

All issues of Good Bird Magazine can now be down-

loaded from www.GoodBirdInc.com. (While you are

there check out our spiffy new website.) We will contin-

ue to print and mail hard copies of future issues, as well

as have them available for download.

Back to the topic of food as a reinforcer, it came to my

attention recently due to some comments sent to the

Good Bird Inc YouTube site

(www.youtube.com/GoodBirdInc). On this site I have

posted a few videos of training in action. While most

comments have been quite complimentary a few

expressed concern that the animals presented behav-

iors for food reinforcers as opposed to attention or

love. I thought I would take this opportunity to

address this concern. Without a doubt attention/love

can be a great positive reinforcerIF your bird finds

attention a pleasurable experience. For some individu-

als this is not the case. An excellent example is shared

in this issue by Cheryl Ward in her article about

DaVinci, a much traumatized horse. This horse had

plenty of history prior to coming to his new home that

taught him to distrust humans. Cheryl could not even

touch him at first. Food reinforcers were the most effi-

cient positive way to build a bridge with this animal.

Read DaVincis story on page 79.

Toby, a Meyers parrot who stars in a YouTube video

and also the Good Bird DVD Parrot Behavior and

Training: An introduction to Positive Reinforcement

Training Part 1, showed such high levels of aggressive

behavior prior to training that handling was not an

option. Attention such as head scratches and praise

resulted in biting behavior. Food

however allowed Tobys caregiv-

er, Joseph the chance to rebuild

that relationship.

By no means would I consider

these two examples failures

because food was involved. To

the contrary they surpassed what

most have accomplished with

their animals! Now that these two

animals (and caregivers) have

learned how positive reinforce-

ment works there is the opportu-

nity to expand the list of positive

reinforcers to include attention,

tactile, toys, etc. Whether you use food, attention, a

head scratch or verbal praise to reinforce your bird,

remember what matters most is what your bird thinks

of what you have to offer. For more a more detailed dis-

cussion of using food to reinforce behavior download

Good Bird Magazine Volume 1 Issue 1.

More new stuff! In addition to a new website and

downloadable back issues of Good Bird Magazine, I

have another exciting new product to announce. Part 2

of my DVD series is here! DVD 2 is titled Training your

Parrot for the Veterinary Exam. I think this one is even

better than the first. Besides step by step instructions

on how to train behaviors such as getting on a scale,

kenneling, towel restraint, nail trims and more, it also

includes an interview and visit with celebrated avian

veterinarian Dr. Scott Echols. You can order your copy

by visiting www.GoodBirdInc.com. Wholesale orders

also being accepted. Contact info@goodbirdinc.com for

details.

Keep your eye on the Good Bird Inc website and also

sign up for our email newsletter at www.good-

birdinc.com/calendar.html. You will be the first to

know when new products are announced.

Barbara Heidenreich

From the Editors Perch

10 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

Positive Reinforcement for Good Bird

Hi Barb,

I LOVE your article in the last Good Bird Magazine

about oral medications. YOU nailed it. GREAT JOB

Barb really. This information is so important, as YOU

well know. I learned so much from the medical proce-

dure class I took from you on Raising Canine and I

loved that you said someday we hope that this will be

the norm. My heart sang. I learned so much from

watching you in Cleveland at the PEAC conference I

want to try to learn more, more, more.

You are truly one of my favorite people. I also saw

my picture in magazine, thanks.....what a treat. I'm

famous.

Deb Stambul

Hello Barbara,

I attended this weekends Parrot Behavior and

Training Workshops hosted by ACHAP and thorough-

ly enjoyed them. My 26 year old Goffin cockatoo is

already responding to my newly discovered training

techniques! Thank you so much!

Judy Sawin

Barbara

I wanted to get back to you and let you know how

much I enjoyed your workshop on Saturday. I am the

student who came with the lovely Quaker parrot,

Jessie. The information you shared was very helpful.

Your delivery was great! The way you reconciled your

concepts with those of other professionals in the field

was very easy to understand and rational.

Jen Hessel

Barbara,

I just wanted to say a big Thank You for the great

afternoon yesterday! I am impressed how long you

were able to engage Diji my umbrella cockatoo and

how far you progressed with Beebee my red sided

eclectus towards the step up behavior! I learned a lot

from observing you and I hope I can keep it up. I

revised Beebee's shaping plan and now that I've seen

how Diji's reward can be simply attention and food

rewards are not necessarily required for him, I think I'll

be able to guide him to more pleasant activities besides

whining.

I never thought we'll get to work with more than two

birds and your advice regarding the flight/ recall train-

ing with some of my birds is very helpful. So now I'm

thinking of dozens of other training questions I'd like

to go over.

I'm also glad I got your DVD to review your posi-

tioning for the step up training. The part where you

teach the macaw to step up is perfect to apply to further

Beebee's training.

Virama Schmitten

Hello,

The new website is fabulous! I just preordered my

Training your Parrot for the Veterinary Exam DVD and

navigated around on the site a little. It was good to see

you in Houston a few weeks ago. I am inspired to work

on training more and hope to eventually contribute a

success story or two.

Love what you're doing for the pet bird community!

Jennifer White

continued on page 29

Originally Presented at the Grey Poopon Challenge

Conference, Dec. 2000

BACKGROUND

I

once had a psychology professor who started every

class shaking his head chanting, Behavior is noth-

ing if not complex. Truer words were never spo-

ken, and when it comes to the complex behavior of our

companion parrots, we definitely have our hands full.

With the potential for feather plucking, picking, shred-

ding, and clippingincessant screaming, screeching,

calling and shriekingnot to mention biting, nipping,

gnawing and clawing - Im never quite sure who to

turn to for help, Dr. Skinner or Dr. Seuss!

Reducing problem behaviors seems especially com-

plicated. I have this image in mind of the desk toy with

silver balls hanging from strings attached to a wooden

frame. The moment you pull back one of the balls and

release it, the others are set in motion and continue

clicking against one another for a long time before they

finally come to rest. Like this toy, behavior sets in

motion a cascade of perpetual interactions so that ana-

lyzing any one behavior in isolation is essentially

meaningless. Behavior is part of an endless reciprocal

interaction among an individuals genetics, behavioral

history and the environmental context in which the

behavior is performed.

In the face of such complexity, no wonder we all have

moments where we feel overwhelmed and empty-

handed when working with our parrots. To improve

our ability to understand and influence our parrots

behavior, we need a systematic approach which pro-

vides an organized framework and simplifies the seem-

ing complexity that threatens to obscure our view.

AS SIMPLE AS ABC

One such approach to understanding specific behav-

iors is known as ABC analysis. The letters stand for the

three elements of a simplified behavioral equation

which includes the antecedents, behavior, and conse-

quences. With this strategy, we seek to identify through

careful observation the events and conditions that

occur before the target behavior - antecedents, as well as

identifying the results that follow the behavior -conse-

quences. This simple analysis, when paired with keen

observation skills and creative problem-solving, will

help us clarify the way in which the basic components

of behavior are interrelated. It is this clarity that leads

us to important insights and teaching strategies.

HOW TO

There are six steps to analyzing the ABCs: (1) describe

the target behavior in clear, observable terms; (2)

describe the antecedent events that occur and conditions

that exist immediately before the behavior happens; (3)

describe the consequences that immediately follow the

behavior; (4) examine the antecedents, the behavior and

the consequence in sequence; (5) devise new antecedents

and/or consequences to teach new behaviors or change

existing ones; (6) evaluate the outcome.

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 11

The ABCs of Behavior

By S.G. Friedman, Ph.D

What to do if a parrot bites when asked to step up onto the hand from

inside the cage?

Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich

12 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

Lets look at one example: Veda, my otherwise

charming Alexandrine Parakeet, Psittacula eupatria,

bites fast and forcefully when I ask her to step onto my

hand from inside her cage. Seeing the problem in isola-

tion and decked-out in its full complexity, we might

hypothesize that she is aggressive, territorial, hormon-

al, defensive, or dominating. Alternatively, she could

be recalcitrant, stubborn, uncooperative or simply a

stinker who is also spoiled rotten! Any one, or all, of

these hypotheses might be accurate, but in terms of

problem-solving, they serve only to label the behavior,

not resolve it. And, since they do not describe observ-

able behaviors per se, one can never really be sure

about the accuracy of the label.

THE ABC ANALYSIS

What follows is my analysis of Vedas biting behav-

ior using the ABC approach:

First, the background and setting: When asked to

step onto my hand from inside her cage, Veda often,

but not always, bites me! She does not bite under any

other circumstance or in any other situation. She does

it any time of day and with all her family members.

However, once out of her cage, Veda steps up and

down without hesitation, from all locations, including

the top of her cage. For three or four hours each day,

Veda plays happily on her tree perch in the family

room, enjoys cuddles, and generally relaxes by preen-

ing, playing with toys and nibbling. She is by all other

measures an outstanding companion bird.

Step 1: Describe the behavior in observable terms.

Veda widens her eyes, tightens her grip on her perch,

pulls her body back and waits in this position for a sec-

ond or two. If I dont move my hand she bites it hard.

Step 2: Describe the antecedents.

Any time I walk up to Vedas cage, I greet her to let

her know Im there. I open her cage door, slowly put

my hand in front of her and say, Step up, Veda.

Step 3: Describe the consequences.

I remove my bitten hand (hurt and annoyed), and

Veda stays in her cage. Case, or should I say door,

closed.

Step 4: Examine the antecedents, the behavior, and

the consequences in sequence.

Any time I walk up to Vedas cage, I greet her to let

her know Im there; I open her cage door, slowly put

my hand in front of her and say, Step up, Veda. Veda

Seeing the problem in isolation, we might hypothesize that she is aggres-

sive, territorial, hormonal, defensive, or dominating. But do these labels

help resolve the problem?

Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich

THE ABC ANALYSIS

Step 1: Describe the behavior in observable

terms.

Step 2: Describe the antecedents.

Step 3: Describe the consequences.

Step 4: Examine the antecedents, the behavior,

and the consequences in sequence.

Step 5: Devise new antecedents and/or

consequences.

Step 6: Evaluate the outcome

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 13

widens her eyes, tightens her grip on her perch, pulls

her body back and waits in this position for a second or

two. If I dont move my hand, she bites it hard. I

remove my bitten hand (hurt and annoyed), and Veda

stays in her cage.

Lets stop here for a minute to examine the insights

that resulted from this analysis, as it helped me clarify

several important things. First, far from being a biter or

having a biting problem in any chronic or generalized

sense, I learned that Veda displays a very specific set of

responses, in a specific location with a different

antecedent than I had originally assumed. Before ana-

lyzing the ABCs of Vedas biting behavior, I had not

realized that she tenses her body, pulls away from her

perch and widens her eyes in a valiant attempt to warn

me to withdraw. How remarkable!

In this light, it becomes so clear that the critical

antecedent to her biting is not my putting my hand in

her cage; its ignoring her non-aggressive communica-

tion, requesting me to remove it. Only when I ignore

her communication and persist does she resort to bit-

ing. So, who set the silver balls in motion this time,

Veda or me?

It is also evident that by withdrawing my hand and

leaving her in her cage, I was in fact, reinforcing the bit-

ing. With each of these interactions, I was unwittingly,

but explicitly, teaching Veda that biting is an effective

and necessary way to get my hand out of her cage;

apparently so, since warning me non-aggressively did

not work. Im sure she would say it was nothing per-

sonal but that I was quite dense! Cant you just hear

her explaining this to our baby cockatoo? Listen up,

baby. No matter how kind and gentle you want to be,

these humans respond to one thing and one thing only,

aggression. Why, its a jungle in here!

Step 5: Devise new antecedents and/or conse-

quences.

After careful consideration of my options, in this case

I chose to change the antecedents to decrease Vedas

biting. First, I no longer say, Step up! when I want her

to come out of her cage. Instead I ask her, Wanna step

up? If she displays the warning behaviors, I take that

as an unqualified No, but thanks for asking! and I

calmly remove my hand from her cage. I then leave her

cage door open, allowing her to exit how and when she

chooses. As an additional strategy, I trained her to step

onto a perching stick for those rare times when staying

in her cage is not an option. We practice stepping onto

the stick a few times a week, for which she earns an

avalanche of praise and kisses.

Only when I ignore her communication and persist does she resort to biting.

Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich

A caregiver can change the antecedents to decrease biting behavior, such

as retraining the behavior from a different perch.

Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich

Step 6: Evaluate the outcome.

Changing the antecedents to decrease Vedas biting

has been a huge success. Of course it is not surprising

that she no longer bites me. By heeding her warnings, I

dont give her the opportunity, or the reason, to do so.

I continue to present my hand to her and ask if she

wants to step up. If she tenses her stance, pulls away

and/or widens her eyes I remove my hand and go on

to other things (you know, like cleaning cages and

changing water bowls).

What has been very unexpected is that after a few

months of letting her decide how to come out of her

cage, she now rarely declines my offer to take her out

on my hand, choosing instead to step up nicely and

hitch a ride! Who knows maybe the freedom of

choice was important to her or she benefited from more

control over her own destiny; perhaps her trust level

increased when I lowered my apparent dominance.

These are all very interesting possibilities.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

In my opinion, we generally focus too much on conse-

quences to influence behavior. This is especially true of

negative behaviors that we want to decrease or eliminate.

In this way, we limit ourselves to rewarding or punishing

more or less. One of the exciting benefits of this simple

analysis strategy is that it fosters careful consideration of

the antecedents, that is, the things we do to promote

or provoke behavior. Antecedents should be brilliant-

ly arranged to ensure that the appropriate behavior is

facilitated. Doing so makes selecting consequences easy

when the behaviors are all acceptable, the consequences

are all positive! I truly believe (and my experience work-

ing children bears this out) behind every negative behav-

ior is a poorly arranged antecedent.

Some of you may have other insights to add to my

analysis or other solutions to suggest. There is certainly

more than one way to productively analyze a behavior

sequence and more than one useful solution to be

devised. The right analysis and solution is the one that

produces the desired outcome, fits the style in which you

and your bird are comfortable interacting and improves

your relationship with your bird. With Veda, all three cri-

teria were met. In our teaching, we are limited only by

our powers of observation, our creativity and our resolve

to treat our parrots humanely and with compassion.

Of course, behavior is not always as linear as it

appears when analyzing the ABCs; but I think the more

important insight is that none of us, including our

remarkable parrots, behaves in isolation from the

events around us. Although analyzing behavior can

sometimes be like walking into the hall of mirrors at an

amusement park, other times behavior is very straight-

forward. It is at those times that a simplified approach

to analyzing behavior is just what we need to increase

our understanding and develop better teaching strate-

gies. I have found analyzing the ABCs of parrot behav-

ior to be very useful for clarifying the related compo-

nents of many, many different types of behavior. Once

these relationships are clear, the path to creative, posi-

tive solutions and teaching plans become more clear as

well. I hope you will try analyzing the ABCs and find

doing so a helpful addition to your parrot mentors

toolbox.

This original version of this article is reprinted with

permission from the TGPC Internet Conference,

December 2000.

Susan G. Friedman, Ph.D., is a psychology professor at

Utah State University. An applied behaviorist for more than

25 years, her area of expertise is learning and behavior, with

a special emphasis on childrens behavior disorders. Prior to

living in Utah, Susan was a professor at the University of

Colorado after which she lived in Lesotho, Africa for 5 years.

While there, she directed the first American School of

Lesotho.

Susan has written on the topic of learning and behavior for

popular parrot magazines and is the first author on two

chapters found in G. Harrisons Avian Veterinary

Compendium and A. Lueschers Manual Parrot Behavior).

Several of her articles can be found on the web at www.the-

gabrielfoundation.org/HTML/friedman.htm. Susan has

taught animal behavior workshops with Steve Martin at his

ranch facility (see www.naturalencounters.com) and several

zoos around the country; speaks at bird clubs and confer-

ences; and is a core member of the California Condor

Recovery Team. Her well-attended on-line course, Living

and Learning with Parrots: The Fundamental Principles of

Behavior, is described at www.behaviorworks.org.

When asked how she became interested in working with com-

panion parrots in particular, Susan explains with a wink, "I

have always enjoyed working with juvenile delinquents.

14 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 15

INTRODUCTION

W

hen avicultural and parrot behavior writers

refer to `parrots in generalized contexts

they often fall short of the reality that over

350 different species of parrot exist throughout the

world, each adapting to possess a unique suite of

behaviors relevant to the ecological pressures it faces in

its natural environment. One of the most common, and

from my perspective frustrating, generalizations is that

`parrots feed for an hour each morning and an hour

each afternoon. We need to think logically and realize

that each of the 350+ parrot species have adapted

unique feeding behavior schedules relative to ecologi-

cal factors such as resource availability and variability,

the specific energetic quotient of the species-specific

diet and potentially even the differences in physiology

for a species. Scientific field studies have illustrated

that even amongst the few species formally observed,

foraging activities can reach well in excess of 6 hours

per day for some parrot species, compared with ranges

of up to just 72 minutes per day in captive parrots fed

a pellet based diet (Meehan et al, 2003). When consid-

ering the energy expenditure and behavioral activity

required for the duration and complexity of foraging

activity, it should not be surprising that parrots placed

within environments where foraging opportunities are

limited may face potentially accumulative stressors

related to an inability to express exploratory behaviors.

Generalized early morning and late afternoon feeding

sessions are often described for `Cockatoos, a family

incidentally consisting of 12 different species groups in

Australia alone, each with variable feeding and dietary

preferences and habits. Lets take the example of the

Glossy Black Cockatoo Calpyptorynchus lathami, a

species that is highly specific in its diet preference, feed-

ing almost exclusively from the seeds of a single, tree

Enrichment (Part Two)

FORAGING OPPORTUNITY: AN INTEGRAL COMPONENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL ENRICHMENT

By Jim McKendry

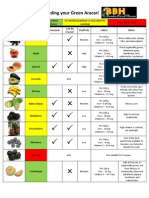

Photo credit: Arlene Alpar New and innovative artificial enrichment items facilitate companion par-

rots `working for food.

Photo credit: Arlene Alpar

These products enable keepers to hide food and chewable items and effec-

tively increase the required feeding duration.

Photo credit: Arlene Alpar

16 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

genus. It is reasonable to assume that the obtainable

energy from a single Casuarina sp. cone is such that a

Glossy Black Cockatoo must engage in feeding for

extensive periods of the day to satisfy its baseline ener-

gy requirements for survival, hence we can observe

species such as Glossies feeding in their native habitat

frequently throughout the day. My observations of

other black cockatoo species such as Yellow-tailed and

Red-tailed indicate that they will also engage in feeding

for extensive periods during the day depending on

environmental conditions. I have video footage of Red-

tailed Black cockatoos feeding at midday on a 33 degree

Celsius day, having been observed feeding at regular

intervals from 6am onwards. So much for `an hour in

the morning. Foraging enrichment is perhaps the most

significant husbandry element required for ensuring

that the potential for stereotypical and displaced behav-

iors is minimized, particularly for species that have

proven to be highly prone to behavioral abnormality

onset due to activity deficit in captivity.

In a recent scientific study investigating the correla-

tion between foraging opportunity and feather picking

in captive parrots, Meehan et al (2003), found that lack

of foraging complexity and opportunities to actively

forage for food is directly linked to the establishment of

psychogenic feather picking in Amazon parrots.

Beyond feather picking reduction in response to

increased foraging opportunity, Meehan et al (2004)

found that by pairing foraging enrichment with con-

specific `pair housing completely prevented the devel-

opment of stereotypical behaviors in Orange-winged

Amazon parrots whilst stereotypical behaviors were

found to progressively develop amongst individuals of

the same species when deprived of such enrichment

and social interactivity. This highlights the importance

of reflecting on the suitability of maintaining singly

kept parrots within companion animal contexts and

depriving them of natural, social interactions.

My own work with Gang-Gang cockatoos strongly

correlates with the findings of these studies and it was

with great relief that I finally had some qualified scien-

tific research to support my own hypothetical consid-

erations for the Gang-Gangs I had been working with

for a number of years. Indeed, simply by reviewing the

dynamics of diet provision and increasing foraging

opportunities by focusing on natural food sources

Foraging stimulus from an early age will help to reduce behaviours such

as feather picking.

Photo credit: Jim McKendry

Working for Casuarina cone seeds is an essential component of the daily

diet of this pair.

Photo credit: Jim McKendry

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 17

resulted in the extinction of feather chewing behaviors

in three of the four Gang-Gang cockatoos I have reha-

bilitated, the fourth being resolved using a combina-

tion of improved foraging strategies, modification of

the social environment and reducing imprinting relat-

ed dependencies over time.

Food presentation variability is perhaps the key

component in achieving a dynamic foraging envi-

ronment for both companion and aviary parrot keep-

ers. The following suggestions can be implemented

to enhance foraging and exploratory behaviors with

captive parrots:

Size: Simply changing the size of food items can

have an effect on rate and duration of engagement

in feeding by parrots kept in captivity. Finely

chopping foods into very small pieces often

extends feeding sessions and minimizes waste by

reducing the likelihood of large chunks of food

being discarded. Alternatively, for some species,

larger chunks skewered on to feeding sticks or

perch extensions and hung at difficult to access

locations within the enclosure may also serve to

extend feeding and foraging duration. Parrots

need to be encouraged to `work more for their

food in captivity!

Texture: By changing the texture of food types

such as pureeing blends of fruits, grating instead

Split logs provide great opportunities to hide food items.

Photo credit: Jim McKendry

Natural substrate in aviaries facilitates excellent foraging for social flocks.

Photo credit: Jim McKendry

Food treats placed throughout an aviary keep a parrot engaged and

searching for extended periods and reduces the potential for stereotypical

behaviours developing.

Photo credit: Jim McKendry

18 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

of chopping vegetables, leaving the skin on fresh

foods despite the perceived `wastage and also by

accessing obscure or exotic fruit and vegetable

types, may result in renewed enthusiasm for previ-

ously discarded fresh foods.

Seasonal Availability: Research done on the

nomadic foraging behaviors of parrot species such

as Macaws (Renton, 2002) and my own observa-

tions of many Australian parrot species, indicates

that their feeding patterns and geographical move-

ments follow the seasonal availability of a range of

diverse foods. This can be duplicated to some

degree in captivity by varying the diet dependant

on seasonal availability of fresh foods rather than

providing the same base diet year round.

Location and Access: Wild parrots `work for their

food and therefore much of their metabolized ener-

gy is used for this purpose. By varying food loca-

tion and being creative with its presentation in

captivity we can increase activity, feeding duration

and behavioral function with the aim of reducing

behavioral abnormalities. More food bowls, less

food in each, varied and even obscure positioning

it creates an interesting environment that pro-

motes behavioral and cognitive activity.

Amount: The amount of each food type provided

in a varied diet can change. Providing formulated

foods as an essential base to the diet assists with

the ability to carefully vary amounts of other

dietary items such as nuts, seeds, fruits, vegetables

and live-food and maintain the nutritional integri-

ty of the overall weekly consumption. Varying the

amount of each food component, in combination

with changing location and presentation, can

result in an environment that facilitates stimula-

tion via exploration by the parrot.

Live Food: While zoos have been using live foods,

such as mealworms, for many years, companion par-

rot owners and many breeders have not investigated

this diet option. As a keeper at Currumbin Wildlife

Sanctuary I was able to see the application of live

food feeding firsthand and the high degree of accept-

ance of mealworms amongst a diverse range of

Australian native parrot species in the collection.

Incredible Animals will customize a behavior

program for youbecause each pet/owner is

unique and the consultation should be specific

to your needs.

Consultations services are available in your home

or by phone.

Heidi has consulted on animal behavior for

Walt Disney World, London and Dublin Zoos

and Zoo New England.

Incredible Animals provides positive reinforcement

training, behavior management techniques,

husbandry skills, and habitat development.

Specializing in birds catering to all exotic pets

and the people they own.

Feel Like You Live In A Zoo?

Incredible Animals

Heidi Fowle, Behavioral Consultant

617-269-9863 creatureteacherheidi@yahoo.com

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 19

Mealworms can be `gutloaded with additional nutri-

ents that may be deficient in the diet of the species

and once accepted prove to be highly palatable. By

presenting items such as mealworms in simple ways

such as inside open logs or sprinkled over a foraging

tray of suitable substrate for grazing species results

in the stimulation of natural exploratory behaviors

that are being actively reinforced.

Beyond the above strategies, perhaps the simplest

and most effective is the daily provision of `browse

a term used to describe natural foraging substances

such as leafy, seed and flower producing branches.

Investigating the natural history of the species you

keep and providing fresh foraging material represen-

tative of their natural environment and diet, or a

suitable substitute, can provide a range of mental

and physical benefits to the birds. The innate foun-

dations and learned spectrum of foraging behaviors

of many parrot species are thankfully now being

more closely considered. My first-hand observations

with Gang-Gang cockatoos suggest that this particu-

lar species exhibits characteristics of an intense for-

aging need that when unsatisfied in captive condi-

tions serves as a primary precursor to the onset of

feather picking behaviors. Aphenomenon referred to

as `contra-freeloading behavior can be seen daily

amongst my small flock of Gang-Gang cockatoos,

who will actively forage and work to procure food

amongst Corymbia, Eucalypt and Casuarina browse

for many hours in preference to accessing free feed

offerings. This has reinforced my belief that this

species requires particularly diligent husbandry

standards for optimal behavioral health. Where con-

tra-freeloading behavior reconciles with `Optimal

Foraging theories is yet to be fully understood, but

at this stage we can be confident in suggesting that

we need to seriously consider the importance of pro-

viding opportunities for parrots to be provided with

feeding challenges as an important component of

achieving optimum conditions in captivity.

CONCLUSION:

It has now been scientifically demonstrated that

enhanced foraging enrichment programs significantly

reduce a range of behavioral abnormalities commonly

Even a simple palm frond can provide hours of opportunity for a parrot to actively exercise.

Photo credit: Arlene Alpar

20 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

seen in captive parrots and enhances the long-term

well-being and preparedness for life if provided from

as early an age as possible. It would be extremely pro-

gressive of parrot owners to consider at least applying

some of these enrichment principles to the husbandry

of parrots in their care.

REFERENCES

Meehan, C.L., Millam, J.R. & Mench, J.A. 2003, Foraging

opportunity and increased physical complexity both

prevent and reduce psychogenic feather picking by

young Amazon parrots, Applied Animal Behavior

Science, vol. 80, pp. 71-85.

Meehan, C.L., Garner, J.P. & Mench, J.A. 2004,

Environmental enrichment and development of cage

stereotypy in Orange-winged Amazon parrots

Amazona amazonica, Developmental Psychobiology, vol,

44, pp. 209-218.

Renton, K. 2002, Seasonal variation in occurrence of

macaws along a rainforest river, Journal of Field

Ornithology, vol. 73, pp. 15-19.

Jim has been intensively keeping parrots in both companion

and aviary environments for over 10 years. During that time

he has focused on developing an understanding of the specific

behavioral and general care dynamics of captive parrot species.

He has a Bachelors degree in Teaching (ACU) and a Bachelor

of Applied Science degree from the University of Queensland.

Jim operates Parrot Behavior & Enrichment Consultations

and has provided consultative services to hundreds of parrot

owners, both within Australia and internationally, as well as for

pet-keeping magazines and journals. He is the founder of the

Companion Parrot Support Network, is a former committee

member and Companion Parrot Consultant for the Parrot

Society of Australia Inc and has lectured for numerous bird

clubs and societies in South-east Queensland. Jim currently

writes a regular column Pet Parrot Pointers for Australian

Birdkeeper Magazine and is an editorial consultant on parrot

behavior for this publication.

During 2003/2004 Jim worked as a Presentations Keeper at

Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary. This professional experience

further enhanced his animal training skills with a range of

avian species such as raptors, water birds and of course, par-

rots. He is an active member of the International Association of

Avian Trainers and Educators and the writer and presenter of

the Parrot Behavior & Care workshops held at Currumbin

Wildlife Sanctuary.

In recent years, Jim has focused almost exclusively on work-

ing with Gang-Gang Cockatoos and rehabilitating juvenile

feather chewers of this species. He currently cares for a small

collection of Australian Cockatoos and an African Grey Parrot.

He provides private consultation services via phone, e-mail and

in-home access that cater for all aspects of companion parrot

behavior, enrichment and general care. For more information

on Parrot Behavior & Enrichment Consultations range of serv-

ices please visit www.pbec.com.au.

Corymbia flowers provide wonderful foraging enrichment for lorikeet

species such as the Purple-crowned Lorikeet.

Photo credit: Jim McKendry

Safe flowers can provide great natural foraging enrichment items for

species such as these Amazons.

Photo credit: Arlene Alpar

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 21

What is Your Bird Saying?

LEARNING TO READ AND INTERPRET BIRD BODY LANGUAGE

By Barbara Heidenreich

1._____________________ 2._____________________ 3._____________________

5.___________________________________

Training is a way for people to communicate to parrots. But how do parrots communicate to us? They commu-

nicate through their body language. Subtle changes in feather position, eye position and body posture can give us

a glimpse into what a bird might be thinking. Some postures indicate fear or aggression. Other let us know our

birds are relaxed and comfortable. The greater our sensitivity is to our birds body language the easier it will be for

us to avoid doing things that might cause our birds to be uncomfortable. In turn we can help foster an even

stronger relationship based on trust.

Look at the following photos and see if you can read and interpret the body language of these birds. Apractice

that can help you fine tune your skills is to try to describe the exact body postures you are observing, rather than

using general labels such as content or nervous. Answers are on page 85.

WHAT IS THIS BIRDS BODY LANGUAGE SAYING?

Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich

Photo credit: Barbara Heidenreich

5.___________________________________

Photo credit: Roelant Jonker/Grace Innemee www.cityparrots.org

22 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

Photo credit: Roelant Jonker/ Grace Innemee www.CityParrots.org

Quoth the Raven...er, we mean the Parrot

I once had a sparrow alight upon my shoulder for a

moment, while I was hoeing in a village garden, and I felt

that I was more distinguished by that circumstance that I

should have been by any epaulet I could have worn.

Henry David Thoreau

US Transcendentalist author (1817 - 1862)

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 23

Bite Me!

By Gay Noeth

B

iting is one of the most common, complained

about parrot behaviors. It is so common that

many people say that if you own a parrot you are

going to eventually get bit, as if to imply that its just

their nature to bite. Another camp says biting is a

learned behavior. This isnt entirely true either. They

have a beak, they need to eat, they need to chew, they

need to take bites of food. No, they come with a form

of biting already in their repertoire. Its much more a

matter of how they use that biting ability.

Lets see if we can make sense out of the two above

statements and where they might fit in with our pets.

Lets take a closer look at what biting may mean from

the parrots point of view and how biting may become

a problem behavior.

BITING AS A NATURAL BEHAVIOR

As noted, birds have beaks and the ability to bite

down on anything that enters those beaks. For a bird to

bite down, the number one thing to consider is that

there must be proximity. If whatever is being bitten

cant enter the beak (even the tip) it would be impossi-

ble for the bird to bite it. So we can start with one fact.

Proximity or nearness is a must for a bite to occur!

Birds dont have hands. Parrots sense of exploratory

touch is via beak, tongue and feet. It is common for

young birds to explore new things with their beak and

tongue. This in itself does not a biter make. It is our job,

as caregivers, at this stage to reinforce gentle exploration

and to divert that exploration to appropriate items.

Parrots chew. Give them acceptable things to chew.

BITING AS A LEARNED BEHAVIOR

Why would a parrot bite his caregiver? In human

terms it could be an attempt to say no to a request.

For example, if someone approaches us and tells us to

do something, we have vocal skills to say no. If our

no is ignored, we may repeat it and perhaps turn

away. If the person persists we may push them away. A

parrot doesnt necessarily have the human vocal skills

to appropriately communicate no, although there is

no doubt that they have BIRD signals to convey the

same message.

It should also be

noted that many of our pet

birds are being kept clipped. If

they find themselves in a frightening

situation, what options do they have for

self defense? They cant flee very easily. In many

cases the other option available to them is to bite in

hopes of getting rid of the feared object or offender.

That bite would again be a means of saying no,

although with a slightly different meaning. In this sit-

uation it would be self preservation, similar to a

human being attacked and doing whatever was nec-

essary to stop the attacker.

In both cases, the bite is a NO or STOP response to

some sort of aversive stimuli. The bird bites to tell you

no, it doesnt want to partake in something, or no

you must keep away from me. The bite was a final

way for the bird to get us to pay attention to what it

was telling us, much like a human stomping their foot

to add emphasis! Imagine it as a loud NO!

The problem now is that it is too late to change the

event, the bite has already occurred. The consequence

in the birds eye will now vary depending on what hap-

pened after the bite. Did you finally understand the

no and back away? Did you teach the bird that for

you to understand your birds discomfort you needed

him to bite? This is where the statement biting is a

learned behavior gets its foundation. We teach the

bird that to get us to stop, the bird should bite us.

BITING FOR ATTENTION

Once biting is solid in the birds behavioral bank, it

may become generalized to get us to pay attention in

different situations, not just as a means to say no. It

Photo Credit: Gay Noeth

24 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

draws our attention when we are ignoring the bird, it

draws our attention when it wants something, it gets us

to notice when it doesnt want something, and it gets

our regard when the bird is scared.

In our fast paced world these days, almost everyone

is running into time constraints. We often find our-

selves juggling several jobs at a time. Sometimes (unin-

tentionally) our birds become part of this juggling. Its

during our rush of life or a result of, that we can some-

times teach our birds to bite to get our attention.

Perhaps you are busy watching a show or reading

emails with your bird close by and your bird wants

some direct attention. Sometimes in this scene your

bird will give you a little nip. What too often happens

in this case is that the caregiver will reach out and pet

his or her bird without even giving thought to what

message might have been conveyed to the bird. If this

is repeated a few times the bird learns that if the care-

giver is distracted, a small nip will bring his or her

attention back.

If this type of bite occurs, you can very quietly and

calmly remove your bird from your person and set him

on a nearby perch. In a few moments your bird can be

given the opportunity to rejoin you and gain the

desired attention. If your bird wants to be on you while

you are doing other things just remember to give your

bird that scratch or attention every so often for sitting

calmly without biting.

BODY LANGUAGE AND BITING

Why should a bird have to bite us to tell us some-

thing? What would it do to another bird in the same sit-

uation? It is true that parrots do nip at each other, but

seldom with the ferocity shown to some humans and

not generally as a first reaction.

In a typical parrot to parrot confrontation, two things

initially occur at about the same time. Feathers will lift

slightly, posture will become more upright to appear

larger and eyes will pin (pupils constrict). If neither

bird backs down a bit it is common to hear a slight

squawk and to see feathers raise more. Some species

may slick their feathers tight in this situation. At this

stage parrots with crests will have them fully upright

and tail feathers will also usually be fanned. Often one

of the birds will back down or move away. The postur-

ing is all that is required. It should be the same with us.

All we should require from the bird is the smallest of

body language.

Do we fail to notice those initial slight feather posi-

tion changes, the pinning of the eyes? Do we continue

to force our will when the feathers are raised more?

What other option did we actually give our birds when

we failed to notice these changes? By ignoring these

overt body language displays, we often leave the bird

no other choice but to bite us to get his point across.

NATURAL OR LEARNED BEHAVIOR

Birds learn, as do all living things. If our responses

teach them that we never pay attention to the subtle

signs that generally precede a bite, they may learn that

those signs are an unnecessary and wasteful use of

energy. They will simply quit showing them as an indi-

vidual step and instead show them at the same time as

the bite is occurring. We teach them to cut to the chase.

It is true that parrots do nip at each other, but seldom with the ferocity

shown to some humans and not generally as a first reaction.

Photo Credit: Gay Noeth

By ignoring these overt body language displays, we left the bird no other

choice but to bite us to get his point across.

Photo Credit: Gay Noeth

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 25

Is biting a learned behavior or is it a natural behavior?

The answer is that its a combination of both. They have

a beak for a reason and its only natural for them to use it

when life necessitates that, but we certainly teach them to

use it far more than it would ever be used in the wild.

ADDRESSING BITING BEHAVIOR

Hopefully youve already been able to identify what

needs to be changed when dealing with your bird.

What is the purpose of your birds biting? Is it to

remove you in some way? Is it to gain your attention?

Is it just to voice a no response? Quite likely, its all of

the above at different times. Biting can become multi-

functional because it is one thing human caretakers

notice. Different antecedents (situations) may result in

a bite. Perhaps the way you approached or your ener-

gy level, or maybe it is fear mediated but regardless of

the reason, the bird is trying to tell you something.

How do you proceed once you know situations that

foster biting behavior? Remember, one of the first facts

about biting was the need for proximity. Keep that in

mind for your interactions. If your bird cant reach your

skin, he cant bite you. No! You dont need to keep your

distance forever. You likely want a relationship with

your bird that allows closeness, but as a temporary

measure you may have to limit this.

The different places to begin addressing this problem

are as varied as the reasons for the bite. Each person

will have to look at their own individual situation and

decide where that starting place is. Ive given just a few

ideas of possible starting places for the most common

types of bites but again I must stress, you must look at

what function the bite has for your bird. What is your

bird getting out of the bite? Its only once you have an

understanding of this that you can address the biting in

the correct manner.

IM SCARED

If an animal bites as a fear response, the first thing to

identify is the subject of the fear. Is it an overall fear of

everything or a more refined fear? With any type of fear

biting it is important to slowly desensitize the bird

from the feared item by shaping proximity to the item.

If its fear of a person, I would suggest that for the first

few days the person quietly walk by the cage and drop

a favorite treat in a food bowl. Try to do this several

times a day. No requests on the bird, no lingering at the

cage, just drop and move on. Try to notice as you are

doing this, at what distance the body language changes

to comfort. If after a few days of dropping in the treat,

the bird is now looking towards the person when he or

she enters, you can proceed with the following:

Begin with the person at the closest distance that the

bird shows body language indicative of comfort

(This is where having watched that previous body

language will help you)

Have the person start to approach the bird, Note the

distance at which the bird showed its first sign of

slight unease.

Have the person step a bit farther away than this dis-

tance. Watch the bird body language to ensure there

is comfort. If the bird is still moving around his cage,

paying attention to things like his toys and food, the

bird is still in his comfort zone.

Have the person remain in the same position for a

few moments. When its time to move away, have

the person walk by the cage and drop a favorite treat

in the bowl with no other demands. Do not try to

push closer.

Indicate the distance achieved by putting a piece of

tape on the floor. Repeat this distance several times

with the bird receiving a treat after each short session.

Over time the person can advance closer, but just

slightly. I cant stress enough that these advances

may be very tiny increments, which is why I suggest

the marker on the floor. Repeat the procedure above

doing several sessions at that distance.

During this process the bird is becoming systemati-

cally desensitized to the person and also learning that

good things (treats) come from that person.

GETTING TO YES

Are you asking or demanding a behavior from your

parrot? Is it a behavior the bird can easily do? Is it a

behavior the bird really needs to do at this particular

moment? The secret in the cases of a bird that bites to

say no is to train the bird to say yes! in the desired

situation.

26 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

The most common request that results in a bite is the

step up request. There are many variables to be consid-

ered if a bird seems apprehensive about stepping up.

What have the past consequences taught the parrot about

stepping up? Where is your hand and how is it placed

when you cue the behavior? Are there more distractions

in the room than normal that are confusing to the bird?

Parrots want to step upwards. By this I mean the

hand should be held higher than foot level of the

bird. The hand should also be held perfectly still until

both feet are firmly on the hand and the bird has

regained his balance. Too often we begin moving the

bird, before that second foot is even on our hand. We

basically boost the bird off of its perch. Many parrots

find this uncomfortable and may be reluctant to step

up the next time a hand is offered. It is also conducive

to building trust to let the hand remain in the same

spot long enough to give the bird the option of step-

ping back down should he choose to do so.

If your bird appears to say no when you are shap-

ing a behavior (such as stepping up) you need to take a

closer look and make sure you arent requesting too big

of an increment or more than the bird understands at

that time. You may need to slow down a little or move

back a step in your shaping plan. It isnt so much say-

ing no as it is saying I dont understand and Im get-

ting frustrated.

CHANGING YOUR APPROACH

Remember that a parrot needs to be in proximity to

bite. One way to avoid being bit when cueing for the

behavior of step up, is to keep your hand at a distance

from the bird while you make the request. Only move

your hand in for the bird to step onto once it has shown

the desire or willingness to actually step up. This is

generally noted by the bird lifting one foot into the air.

If for any reason the bird decides it doesnt want to step

up, your hand is not close enough to be bit.

You can also solidify the behavior so that the bird

will step up more often when cued. You can accomplish

this by using positive reinforcement training. Dont just

work on stepping the bird up when its necessary; cue

your parrot for the behavior from many different loca-

tions throughout the day, always reinforcing the behav-

ior with something desired by your bird. This can be as

simple as allowing the bird to step back down where it

was. Every step up behavior doesnt need to be a move

to a new location. Soon, because of all the positive rein-

forcement given, your bird will be willingly stepping

up whenever you request it. Just remember to keep it

positively reinforcing.

CONCLUSION

Usually there is little doubt after reviewing the reasons

for repeated biting that we have reinforced the behavior.

Biting is a behavior that simply by virtue of its nature on

our human skin, is very difficult not to reinforce (give the

bird a desired outcome). We cant help but notice a bite.

We cant help but pay attention. We also know that par-

rots certainly have a beak and the knowledge of how to

use it, but it is generally us humans that prompt its use

on human skin.

The solution is to listen to our birds and be observant

to what they are trying to tell us. Rather than correct a bit-

ing problem once it has developed, a far better solution

would be to never teach them the need to bite us in the

first place. Always keep in mind that there just may be

some things your bird doesn't like, or some situations

that make him uneasy. Respect that, rather than push

them into biting.

Gay Noeth lives with her husband and animals (birds, goats,

rabbits and a dog) near Paradise Hill Sask, Canada. They have

been living with birds for the last twelve years and raising

small numbers of African Greys, poicephalus and parrotlets for

the past seven years. Gay has been very interested in the behav-

ioral aspects of birds for the last four years, attending different

seminars and workshops to learn more. Gay is constantly try-

ing to better the lives of her personal pets, plus learn how to

help others better live with their pets.

Parrots want to step upwards. By this I mean the hand should be held

higher than foot level of the bird.

Photo Credit: Gay Noeth

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 27

G

ood Bird Magazine takes a pretty scientific

approach to behavior. We also fully understand

that the A word, (anthropomorphism: pro-

jecting human emotions and feelings to an animal) can

cause a miss-interpretation of behavior. But dont let

that mislead you! We also enjoy a loving relationship

with our birds and get a kick out of those stories about

birds doing things that seem uncharacteristically

human. Perhaps the tales we enjoy the most are the

ones in which a parrot seems to say the right thing at

the right time. We realize birds may or may not under-

stand what they are saying, but it makes us laugh any-

way. Here are some stories we found amusing, con-

tributed by our readers.

AN EVENING AT HOME WITH PICKLES

By Georgi Abbott

Pickles is a Congo African grey parrot owned by

Georgi and Neil Abbott Here is a story courtesy of

Georgi.

The phone rings as Pickles is dining on his snack of

green beans. As it's ringing, Pickles is repeating the

ringing in the bowl which he discovers produces a

really interesting echo. So while Neil answers the

phone, Pickles continues the bowl ringing. He real-

izes the beans are impeding the good sounds so he

tosses them out, one by one. But now he notices

daddy is engrossed in a telephone conversation and

wants in on the act.

Pickles often carries on telephone conversations

with himself and in between, he makes what must be

the sound he hears of someone talking on the other

end of the phone kind of an electronic garbling. So

while Neil is talking, Pickles' own conversation goes

like this ... Ring. Beep. Hello? (garble) What?

(garble) mmmmm. (garble) Everybody's home.

(garble) Huh? (garble) Wanna good story? (garble)

Okay bye. Beep.

Pickles has put an end to his conversation and

decides Daddy must be coached to do so too . Okay

bye. Beep. Okay bye. Beep. Okay BYE. Beep. OKAY

BYE!!! Daddeeeeeeeeeee! Go BYE!!!!!!

Neil finally tells his friend that Pickles has ordered

him off the phone and hangs up. Neil tells Pickles what

a brat he is while Pickles skips away, head bobbing and

snickering. Neil goes after him Come here my lit-

tle Chickadee. Pickles does the chickadee song,

Chicka dee dee dee but it quickly changes to Dad

dee dee dee.

Neil asks Pickles if hes a Chickadee but Pickles

explains that he is in fact a Big Eagle. He doesnt do the

usual raising of wings that other parrots do, he raises

himself as tall and fluffy as possible and exclaims

Beeeeagle.

Fine, says Neil Step up Big Eagle. And takes him

to the couch beneath the window to bird and people

watch. Pickles becomes a fierce guard dog. Athena,

our Doberman, likes to sit on the corner of the couch

and bark at anybody walking by and Pickles has taken

up the cause. He sits in the same spot and barks Woof

Woof Woof! This alerts Athena who comes to join

him. The two of them stand barking their warnings to

all intruders. I can only imagine what this looks like to

people walking by.

We settle in to watch American Idol. Pickles is

American Idols BIGGEST fan and is always in com-

plete disagreement with Simon. The worse the singer,

Out of the Mouths of Parrots

Photo credit: Georgi Abbott

28 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

the more Pickles sings along interjecting with

Whatta good song! Woo hoo!

After American Idol is over, we watch an amusing

sitcom. Neil and I arent laughing out loud but we

notice that Pickles is and always at the right time.

What the heck? We thought our bird particularly

clever with an exceptional understanding of humor

until we realized the show was either using canned

laughter or a live audience and Pickles was picking

up on it.

A commercial comes on and I go to the kitchen to

make a snack. Neil and I always let each other know

when the program comes back on and before I finish

making the snacks, I hear him say Its on. So I drop

everything to go back to the couch. But the commer-

cials still on. I ask Neil why he called me back but he

said he didnt. We look at Pickles. Cant be. I go

back to the kitchen and seconds later I hear Its on.

I go back to find Neil shrugging and pointing accus-

ingly at Pickles.

Since then, when Pickles announces a program is

on, we have to warn the other No its not. And of

course Pickles has picked that up too so all we hear

during commercials is him saying Its on. No its

not. Its on. No its not. Luckily, Pickles had decid-

ed that commercials are whats really important so

mostly he only announces Its on when the com-

mercials start. Pickles knows many commercials by

heart and announces all the sounds and words before

they happen.

Later, Pickles perches on the arm of the couch next to

Neil's face and asks Wanna snack? Neil agrees and

hands him a pine nut. Want anudder snack? Neil

gives him another. About every three or four snacks,

Pickles cranes his neck out to give and receive a kiss

from daddy.

Snack time is over and Pickles asks for a good story

and tells daddy to talk to the beak. He says this

while placing his beak against Neil's lips or cheek I

don't think he really cares about the story. He just likes

the sound and feel of the vibration against his beak.

Today it's the lips and Neil's going cross eyed trying to

watch Pickles eyes for signs that Pickles is not pleased

at this particular story. He's a gentle bird but only a

fool would get complacent with a bird around their

face. But all is well and Pickles draws bored with Neil's

tale of how the chickadees like to eat Mountain Ash

berries and how they eat so many that they become

funny little drunken flyers.

Its almost bed time and Pickles is getting sleepy.

Neil is watching TV while lying down with his arm

draped across the back of the couch, absent minded-

ly scratching Pickles neck. Pickles grabs Neils fin-

ger to swing upside down but Neil isnt prepared.

Pickles slides, on his back, down the back of the

couch, across Neils chest, continuing to slide across

the couch seat, landing on the floor still on his

back. He never flapped his wings or panicked, just

shot from top to bottom like a sleek upside down,

out-of-control little bobsled then lay on his back on

the floor with little footsies clenching and unclench-

ing as a sign for Neil to offer him a finger to grab

hold of.

I thought, well that will teach Pickles to hold onto

us a little better but nope once rescued and brought

back to the top, hanging upside down, he let go to do

it all over again. But this time he landed wedged

between Neil and the back of the couch. Much to

Pickles disappointment, he was never again able to

duplicate that same downhill momentum. So much

for the 2010 Winter Olympics.

Now its time for bed and after feeding Pickles his

nighttime almond, Pickles climbs into his cage and

into his tent. He waits for a minute or two then

pokes his head out to say Lights off! backs up and

parks himself. We turn out his light and partially

cover his cage while Pickles tucks his head under his

wing to dream of snacks and toys and songs and

scratches to come.

continued from page 10

POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT

FOR GOOD BIRD

Hi Barbara,

This is a long shot, I know.......but I will ask.

I am interested in purchasing a particular back issue

of Good Bird Magazine that is not available on your

website. I have ALL issues but that one and I do so

want to include that issue to complete my set. I am

hoping, perhaps, that you might have a copy stashed

somewhere that you could part with.

Do you have Volume 1 Issue 2 / Summer 2005 available?

I LOVE your magazine and books, your philosophies

and your work with parrots.

I hope to meet you at the Canada conference with

Susan Friedman in April 2007.

Thanks,

Mary Bacon

Exquisite Exotics Aviary

www.CongoAfricanGreyParrots.com

www.RedFactorCanaries.com

Customer Service,

I am a new subscriber to your magazine and found it

very helpful and enjoyed reading. What I would like to

know is when did your magazine first come into print?

Was it 2005? If so, I was wondering if you had the four

issues for 2005 and the first three issues for 2006. I would

like to purchase those issues if you still have them.

Thank you,

Paula

Editors response: Good news! All back issues of Good

Bird Magazine are now available for download at the Good

Bird Inc website. Visit this link to get your desired back

issues. www.goodbirdinc.com/backissues.html

www.goodbirdinc.com Good Bird Magazine 29

512-472-3636

goodbird@persidea.com

To reach

bird owners

worldwide

You need to be seen!

Call Persidea today

to reserve your ad space.

30 Good Bird Magazine www.goodbirdinc.com

Learning to Fly is devoted to understanding, dis-

cussing, and exploring the many intricate details of

flight. Whether one chooses to clip flight feathers or

accept the responsibilities of caring for a flighted bird is

a personal decision. However, there are many things to

know and learn about flight that can be helpful to

flighted and non flighted bird owners everywhere.

(Especially when that supposedly non flighted bird

flies out the door!)

Flighted behaviors may not be a good goal for every

bird or caregiver. Should you decide to pursue this

path, keep in mind that flighted behaviors are most

successfully trained to the highest level following a

structured plan based on positive reinforcement train-

ing strategies. Following these practices can reduce, but

do not eliminate, the risk of flying birds outdoors.

FLIGHTED BIRDS IN THE HOME

By Barbara Heidenreich

Flight is engaging, stunning, beautiful to watch and

quite frankly usually fun to train. I am often asked by

enthusiastic parrot owners who feel the same if they

should consider allowing their birds to be flighted.

Despite my love of flighted parrots this question can be

difficult to answer. So much needs to be taken into con-

sideration. The first question to consider is if the bird is

even a good candidate for flight, or will he realistically

even be able to learn to fly? The second is if the mem-

bers of the household are prepared to put on their pos-

itive reinforcement training ponchos and transform

into the best trainers they can be!

This is because training and managing behavior of

flighted companion parrots can present a new set of

challenges much different from their non flighted

counter parts. Flighted parrots are afforded better

opportunity to make choices. For example should a

flighted parrot find a situation to be an aversive expe-

rience it can choose to fly away. This appears to have an

important effect on influencing certain behaviors. For

example if a parrot is being approached for the behav-

ior of step up onto the hand, and the person requesting

the behavior resorts to negative reinforcement as a

training strategy, rather than bite, typically the parrot

will fly away. One benefit to this is that the parrot is not

engaging in aggressive behavior. For the inexperienced

trainer this can help avoid teaching a bird to bite for a

desired result in the given example. However this also

presents the new challenge of learning how to train the

behavior without the use of force or aversives. How is