Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

LABOR Digest

Transféré par

hello_hoarder0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

27 vues2 pagesLabStan

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentLabStan

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

27 vues2 pagesLABOR Digest

Transféré par

hello_hoarderLabStan

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 2

NERI vs NLRC

Petitioners Virginia G. Neri and Jose Cabelin were hired by BCC, a

corporation engaged in providing technical, maintenance, engineering,

housekeeping, security and other specific services to its clientele.

-They were assigned to work in the Cagayan de Oro City Branch of

respondent FEBTC with Neri as radio/telex operator and Cabelin as

janitor, before being promoted to messenger on 1 April 1989.

On 28 June 1989, petitioners instituted complaints against FEBTC and

BCC to compel Far East to accept them as regular employees and for it

to pay the differential between the wages being paid them by BCC and

those received by FEBTC employees with similar length of service.

Labor Arbiter: held that BCC was an independent contractor as it had

proved that it has substantial capital hence, Neri and Cabelin were

employees of BCC and not of the Far East Bank.

Neri and Cabelins contention:

1. They contend that BCC in engaged in "labor-only" contracting

because it failed to adduce evidence purporting to show that it invested

in the form of tools, equipment, machineries, work premises and other

materials which are necessary in the conduct of its business.

2. That they perform duties which are directly related to the principal

business or operation of FEBTC ( a characteristic of labor only

contracting)

3. If the definition of "labor-only" contracting is to be read in

conjunction with job contracting,

then the only logical conclusion is that

BCC is a "labor only" contractor. Consequently, they must be deemed

employees of respondent bank by operation of law since BCC is merely

an agent of FEBTC following the doctrine laid down in Philippine Bank of

Communications v. National Labor Relations Commission

where it was

ruled that where "labor-only" contracting exists, the Labor Code itself

establishes an employer-employee relationship between the employer

and the employees of the "labor-only" contractor; hence, FEBTC should

be considered the employer of petitioners who are deemed its

employees through its agent, "labor-only" contractor BCC.

ISSUE: Whether or not BCC is engaged in a labor-only contracting. NO, it

is an INDEPENDENT CONTRACTOR.

RULING:

It is well-settled that there is labor-only contracting where:

(a) the person supplying workers to an employer does not have

substantial capital or investment in the form of tools, equipment,

machineries, work premises, among others; and,

(b) the workers recruited and placed by such person are performing

activities which are directly relatedto the principal business of the

employer.

BCC need not prove that it made investments in the form of tools,

equipment, machineries, work premises, among others, because it has

established that it has sufficient capitalization of Php 1.5M. BCC is

therefore a highly capitalized venture and cannot be deemed engaged in

labor-only contracting.

While there may be no evidence that it has investment in the form of

tools, equipment, machineries, work premises, among others, it is

enough that it has substantial capital.

The law does not require both substantial capital and investment in the

form of tools, equipment machineries, etc. This is clear from the use of

the conjunction "or" instead of and. Having established that it has

substantial capital, it was no longer necessary for BCC to further adduce

evidence to prove that it does not fall within the purview of "labor-only"

contracting.

There is even no need for it to refute petitioners' contention that the

activities they perform are directly related to the principal business of

respondent bank. On the other hand, the Court has already taken

judicial notice of the general practice adopted in several government

and private institutions and industries of hiring independent contractors

to perform special services. These services range from janitorial, security

and even technical or other specific services such as those performed by

petitioners Neri and Cabelin. While these services may be considered

directly related to the principal business of the employer,

nevertheless, they are not necessary in the conduct of the

principal business of the employer.

TABAS vs CALIFORNIA

-Petitioners Tabas et al were, prior to their stint with California,

employees of Livi Manpower Services, Inc. (Livi), which subsequently

assigned them to work as "promotional merchandisers" for the former

firm pursuant to a manpower supply agreement.

The agreement provided that California

a. "has no control or supervisions whatsoever over [Livi's]

workers with respect to how they accomplish their work or perform

[Californias] obligation";

b. the Livi "is an independent contractor and nothing herein

contained shall be construed as creating between [California] and [Livi] .

. . the relationship of principal[-]agent or employer[-]employee';

c. that "it is hereby agreed that it is the sole responsibility of

[Livi] to comply with all existing as well as future laws, rules and

regulations pertinent to employment of labor"

d. and that "[California] is free and harmless from any liability

arising from such laws or from any accident that may befall workers and

employees of [Livi] while in the performance of their duties for

[California].

7

-They signed a 6 month contract, which was renewed upon expiration.

Unlike regular California employees, who received not less than

P2,823.00 a month (with benefits), they received P38.56 plus P15.00 in

allowance daily.

-The petitioners now allege that they had become regular California

employees and demand similar benefits. They likewise filed a complaint

for illegal dismissal against California since they refused to rehire them.

Californias contention:

1. It is not the petitioners' employer

2. that the "retrenchment" had been forced by business losses as well as

expiration of contracts.

3. That the petitioners themselves admitted that they were LIVIs direct

employees

4. That they have been hired on a temporal or seasonal basis

Labor Arbiter: ruled that there was no ER-EE relationship between

California and the Petitioners.

ISSUE: WON California is liable against the petitioners. YES!

RULING:

California is liable BY OPERATION OF LAW (Either or Both shoulder

liability)

Notwithstanding the absence of a direct employer-employee

relationship between the employer in whose favor work had been

contracted out by a "labor-only" contractor, and the employees, the

former has the responsibility, together with the "labor-only"

contractor, for any valid labor claims, by operation of law.

The reason, is that the "labor-only" contractor is considered "merely an

agent of the employer,"

and liability must be shouldered by either one

or shared by both.

In the case at bar, Livi performs "manpower services", meaning to say, it

contracts out labor in favor of clients. We hold that it is one( a labor

only) notwithstanding its vehement claims to the contrary, and

notwithstanding the provision of the contract that it is "an independent

contractor."

The nature of one's business is not determined by self-serving

appellations one attaches thereto but by the tests provided by statute

and prevailing case law.

The bare fact that Livi maintains a separate line of business does not

extinguish the equal fact that it has provided California with workers to

pursue the latter's own business. In this connection, we do not agree

that the petitioners had been made to perform activities 'which are not

directly related to the general business of manufacturing,"

California's purported "principal operation activity. " The petitioner's

had been charged with "merchandizing [sic] promotion or sale of the

products of [California] in the different sales outlets in Metro Manila

including task and occational [sic] price tagging," an activity that is

doubtless, an integral part of the manufacturing business. It is not, then,

as if Livi had served as its (California's) promotions or sales arm or agent,

or otherwise, rendered a piece of work it (California) could not have

itself done; Livi, as a placement agency, had simply supplied it with the

manpower necessary to carry out its (California's) merchandising

activities, using its (California's) premises and equipment.

What is LIVIs or Californias liability?

The records show that the petitioners had been given an initial six-

month contract, renewed for another six months.

Accordingly, under Article 281 of the Code, they had become regular

employees-of-California-and had acquired a secure tenure. Hence, they

cannot be separated without due process of law.

California should be warned that retrenchment of workers, unless

clearly warranted, has serious consequences not only on the State's

initiatives to maintain a stable employment record for the country, but

more so, on the workingman himself, amid an environment that is

desperately scarce in jobs.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- CHAPTER 1 Caselette - Accounting CycleDocument51 pagesCHAPTER 1 Caselette - Accounting CycleAnna Parcia75% (4)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Memorandum of Contract For Sale and Purchase of PropertyDocument2 pagesMemorandum of Contract For Sale and Purchase of Propertydummy accountPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter of Intent For A Business TransactionDocument3 pagesLetter of Intent For A Business TransactionArielNicoleCaballeroZaragoza100% (6)

- Practical Accounting 2: Theory & Practice Advanced Accounting Installment SalesDocument65 pagesPractical Accounting 2: Theory & Practice Advanced Accounting Installment Salesclarence dominic espino0% (1)

- Brotherhood Labor Unity Movement Vs ZamoraDocument2 pagesBrotherhood Labor Unity Movement Vs Zamorahello_hoarder100% (1)

- San Beda Insurance Mem AidDocument24 pagesSan Beda Insurance Mem AidSean GalvezPas encore d'évaluation

- Safety Catalog 2015 Arrange - WurthDocument52 pagesSafety Catalog 2015 Arrange - WurthNithin Basheer50% (2)

- GST NotesDocument361 pagesGST NotesDamodar SejpalPas encore d'évaluation

- Jose Rizal Colleges Vs NLRCDocument1 pageJose Rizal Colleges Vs NLRChello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Jose Rizal Colleges Vs NLRCDocument1 pageJose Rizal Colleges Vs NLRChello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- San Juan vs. NLRCDocument1 pageSan Juan vs. NLRChello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Beauty Clinic Business PlanDocument19 pagesBeauty Clinic Business PlanAli Raza AwanPas encore d'évaluation

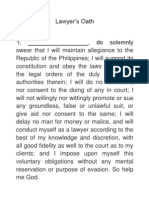

- Lawyer's OathDocument1 pageLawyer's OathKukoy PaktoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Durabuilt Vs NLRCDocument1 pageDurabuilt Vs NLRChello_hoarder100% (1)

- San Miguel Brewery Sales Force UnionDocument1 pageSan Miguel Brewery Sales Force Unionhello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Bautista VS, CA July 6, 2001Document6 pagesBautista VS, CA July 6, 2001Erisa RoxasPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Strategy, Organization Design, and EffectivenessDocument95 pages2 Strategy, Organization Design, and EffectivenessdennisPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Oppo MobilesDocument13 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Oppo MobilesAadithya S100% (2)

- Not FinalDocument1 pageNot Finalhello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Agrarian Reform Law and Soc LegDocument100 pagesAgrarian Reform Law and Soc Leghello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample DesignDocument1 pageSample Designhello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- CorpoDocument5 pagesCorpohello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 81561 January 18, 1991 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee ANDRE MARTI, Accused-AppellantDocument8 pagesG.R. No. 81561 January 18, 1991 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee ANDRE MARTI, Accused-AppellantnikkaremullaPas encore d'évaluation

- CivPro Cases Part 2 (First 10 Cases)Document23 pagesCivPro Cases Part 2 (First 10 Cases)hello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 81561 January 18, 1991 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee ANDRE MARTI, Accused-AppellantDocument8 pagesG.R. No. 81561 January 18, 1991 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee ANDRE MARTI, Accused-AppellantnikkaremullaPas encore d'évaluation

- AgriDocument1 pageAgrihello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Judicial Affidavit FormatDocument1 pageJudicial Affidavit FormatMuhammad Abundi MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- 209 Family Code Part 2Document4 pages209 Family Code Part 2hello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Executive Order No 209Document3 pagesExecutive Order No 209Anonymous fnlSh4KHIgPas encore d'évaluation

- Persons - 3rd Batch Cases 147-148Document32 pagesPersons - 3rd Batch Cases 147-148hello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Union Vs VivarDocument2 pagesUnion Vs Vivarhello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Gerardo B. Concepcion, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and MA. THERESA ALMONTE, RespondentsDocument9 pagesGerardo B. Concepcion, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and MA. THERESA ALMONTE, Respondentshello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Caurdaneta, San Miguel, and Union CasesDocument5 pagesCaurdaneta, San Miguel, and Union Caseshello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Persons - 3rd Batch Cases 147-148Document32 pagesPersons - 3rd Batch Cases 147-148hello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor CasesDocument23 pagesLabor Caseshello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Barrientos v. DaarolDocument1 pageBarrientos v. Daarolhello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Calinisan vs. RoaquinDocument1 pageCalinisan vs. Roaquinhello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- Barrientos v. DaarolDocument1 pageBarrientos v. Daarolhello_hoarderPas encore d'évaluation

- InvoiceDocument1 pageInvoiceVinit Abhang0% (1)

- Copy of Various Types of Tyre SegmentDocument9 pagesCopy of Various Types of Tyre Segmentprasadsawant121Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sin Tax in The PHDocument3 pagesSin Tax in The PHMary Louise R. ConcepcionPas encore d'évaluation

- Sales Personality: Learning CompetenciesDocument11 pagesSales Personality: Learning CompetenciesHannah Sophia MoralesPas encore d'évaluation

- Event: An Event Is Something That Happens at A Given Place and Time For A Reason With Someone orDocument30 pagesEvent: An Event Is Something That Happens at A Given Place and Time For A Reason With Someone orSriganeshPas encore d'évaluation

- Nissan Vs Mitsubishi in PakistanDocument136 pagesNissan Vs Mitsubishi in Pakistansyed usman wazir100% (2)

- Ambuja Cements BrandDocument17 pagesAmbuja Cements BrandVipin KvPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal ReviewDocument9 pagesJournal ReviewYat's YinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unrealized Gross ProfitDocument3 pagesUnrealized Gross Profitels emsPas encore d'évaluation

- Materials Management by Nagesh L TalekarDocument46 pagesMaterials Management by Nagesh L TalekarNagesh TalekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Fast Retailing (UNIQLO)Document7 pagesFast Retailing (UNIQLO)KAR WAI PHOONPas encore d'évaluation

- SCM Excel Based ModelsDocument16 pagesSCM Excel Based ModelssoldastersPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document23 pagesChapter 1AdeebPas encore d'évaluation

- Benson Tolomia Dagoy Banaybanay Cadiente VistaDocument25 pagesBenson Tolomia Dagoy Banaybanay Cadiente VistaClaire VensueloPas encore d'évaluation

- True Solution: UT IO N S OL UT IO NDocument1 pageTrue Solution: UT IO N S OL UT IO NTUSHAR DongrePas encore d'évaluation

- GST RUP11 Patch Document 2342288.1Document11 pagesGST RUP11 Patch Document 2342288.1lkalidas1998Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vice President Sales in San Diego Phoenix Dallas Resume Marian WilsonDocument2 pagesVice President Sales in San Diego Phoenix Dallas Resume Marian WilsonMarianWilsonPas encore d'évaluation

- 00 Memorial de Réplica EnglDocument81 pages00 Memorial de Réplica EnglcefuneslpezPas encore d'évaluation

- Debenhams Report 10 Apr 2019Document28 pagesDebenhams Report 10 Apr 2019danish100% (1)

- Evaluating A Company'S Resources, Capabilities, and CompetitivenessDocument23 pagesEvaluating A Company'S Resources, Capabilities, and CompetitivenessThuyDuongPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Analysis - Cadbury Beverages, Inc. Crush® BrandDocument5 pagesCase Analysis - Cadbury Beverages, Inc. Crush® BrandSamuel Chang100% (1)