Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Court of Appeals Amicus - Gessler V IEC

Transféré par

Colorado Ethics Watch0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

127 vues19 pagesAmicus curiae brief of Colorado Ethics Watch in Gessler v. Grossman, et al., Colorado Court of Appeals Case No. 2014CA670 - appeal of fine for ethics violation

Titre original

Court of Appeals Amicus - Gessler v IEC

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentAmicus curiae brief of Colorado Ethics Watch in Gessler v. Grossman, et al., Colorado Court of Appeals Case No. 2014CA670 - appeal of fine for ethics violation

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

127 vues19 pagesCourt of Appeals Amicus - Gessler V IEC

Transféré par

Colorado Ethics WatchAmicus curiae brief of Colorado Ethics Watch in Gessler v. Grossman, et al., Colorado Court of Appeals Case No. 2014CA670 - appeal of fine for ethics violation

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 19

COLORADO COURT OF APPEALS

Court Address: 2 East 14th Avenue

Denver, CO 80203

District Court for Denver County

Honorable Herbert L. Stern, III

Case No. 13cv0030421

______________________________________

SCOTT GESSLER,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

DAN GROSSMAN, SALLY H. HOPPER, BILL

PINKHAM, MATT SMITH, and ROSEMARY

MARSHALL, in their official capacities as

members of the Independent Ethics Commission,

and THE INDEPENDENT ETHICS

COMMISSION,

Defendants-Appellees.

_______________________________________

Attorneys for Proposed Amicus Curiae Colorado

Ethics Watch:

Luis Toro, #22093

Margaret Perl, #43106

1630 Welton Street, Suite 415

Denver, CO 80202

Telephone: 303-626-2100

Email: ltoro@coloradoforethics.org

pperl@coloradoforethics.org

COURT USE ONLY

________________________

Case No. 2014CA670

BRIEF OF AMI CUS CURI AE COLORADO ETHICS WATCH

IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. STATEMENT OF IDENTITY OF AMICUS CURIAE ...................................... 1

II. ARGUMENT ....................................................................................................... 2

A. Colorados Citizens Enacted Ethics Reform and Created the IEC to Enforce

Constitutional and Statutory Ethical Standards ...................................................... 2

B. The IEC Acted Well Within its Article XXIX Jurisdiction ............................. 6

C. There is No History of the IEC Improperly Expanding its Jurisdiction

Beyond the Authority in Article XXIX ................................................................10

III. CONCLUSION .............................................................................................14

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE .......................................................................15

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ................................................................................16

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

City of Arlington v. FCC, 133 S. Ct. 1863, 1868 (2013) ........................................... 7

Colorado State Civil Service Emp. Ass'n v. Love, 448 P.2d 624, 630 (1968) ........... 9

Developmental Pathways v. Ritter, 178 P.3d 524, 533 (Colo. 2008) .............. passim

Jet Courier Service, Inc. v. Mulei, 771 P.2d 486, 492 (Colo. 1989) ......................... 8

McCool v. Sears, 186 P.3d 147, 150 (Colo. App. 2008) ........................................... 7

North Colo. Medical Ctr., Inc. v. Committee on Anticompetitive Conduct, 914 P.2d

902, 907 (Colo. 1996) ............................................................................................. 7

Sierra Club v. Billingsley, 166 P.3d 309, 312 (Colo. App. 2007). ............................ 7

Statutes

C.R.S. 24-6-402 ....................................................................................................13

C.R.S. 24-9-105 ..................................................................................................6, 9

C.R.S. 24-18-101 .................................................................................................... 4

C.R.S. 24-18-103(1) ............................................................................................6, 8

C.R.S. 24-18-108 ..................................................................................................13

C.R.S. 24-50-117 ..................................................................................................13

Other Authorities

IEC Position Statement 11-01 (2011) ........................................................................ 2

Regulations

1 C.C.R. 1-101 (2012) ............................................................................................. 9

8 C.C.R. 1510-1 (2011) ........................................................................................... 5

Constitutional Provisions

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 1 ...................................................................................2, 6

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 2(6) .................................................................................12

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 3 ...................................................................................2, 4

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 4 ....................................................................................... 3

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 5 ...................................................................................3, 6

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 5(1) ................................................................................... 8

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 5(3)(a) .............................................................................. 4

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 5(3)(b) ............................................................................11

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 5(3)(c) .............................................................................. 5

Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 6 ............................................................................ 5, 8, 14

1

Colorado Ethics Watch, by its undersigned attorneys, respectfully submits its

brief of amicus curiae:

I. STATEMENT OF IDENTITY OF AMI CUS CURI AE

Colorado Ethics Watch (Ethics Watch) is a state-level project and

registered trade name of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a

nonprofit corporation. Since the doors of its Denver office opened in 2006, Ethics

Watch has sought to improve ethics and transparency in Colorado government

using legal tools. Among other things, Ethics Watch has filed five complaints with

the Independent Ethics Commission (IEC) since its inception and submitted

comments in both the 2008 and 2011 IEC rulemaking proceedings. Ethics Watch

maintains a webpage, Eye on the IEC, chronicling the IECs actions since its

inception.

1

Ethics Watch filed the complaint against Secretary of State Gessler that is

the subject of this action, and was forced to act as prosecutor at its own expense

against Gesslers publicly-funded defense team during an eleven-hour hearing on

June 6, 2012. Ethics Watchs perspective as the complaining party and its years of

experience watching IEC actions will assist the court in determining the questions

presented in this review of the District Courts order upholding the IECs findings

1

Eye on the IEC, http://www.coloradoforethics.org/co-pages/eye-on-the-iec/ (last

visited October 3, 2014).

2

and penalty. Specifically, this amicus brief focuses on the issue presented

regarding the scope of the IECs jurisdiction.

II. ARGUMENT

Secretary Gessler raises the specter of a rogue agency ruthlessly expanding

its jurisdiction without proper oversight through judicial review. In reality, the case

under review is a garden-variety breach of public trust matter that falls squarely

within the IECs jurisdiction.

A. Colorados Citizens Enacted Ethics Reform and Created the IEC to

Enforce Constitutional and Statutory Ethical Standards

In order to make certain that elected officials avoid conduct that is in

violation of their public trust or that creates a justifiable impression among

members of the public that such trust is being violated, Colorado citizens passed a

comprehensive ethics reform ballot initiative with 62.5% of Colorado voters in

support.

2

Colo. Const. art. XXIX 1. Amendment 41, now Article XXIX of the

Colorado Constitution, had three major components:

The gift ban, which prohibits lobbyists from giving gifts to public officials

or employees and limits most other gifts to public officials to a value of $50

per year, adjusted for inflation. Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 3; see also IEC

Position Statement 11-01 (2011) (adjusting gift limit to $53 for inflation).

2

Colorado Secretary of State, Colorado Cumulative Report, December 13, 2006,

posted at http://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/electionresults2006G/.

3

The gift ban was the subject of a constitutional challenge that was dismissed

by the Colorado Supreme Court as unripe. Developmental Pathways v.

Ritter, 178 P.3d 524, 533 (Colo. 2008);

The revolving door prohibition, which bans members of the General

Assembly from working as state lobbyists for two years after the expiration

of their terms. Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 4; and

The creation of the IEC as an independent agency empowered to issue

advisory opinions and hear complaints regarding ethics issues arising under

this article and under any other standards of conduct and reporting

requirements as provided by law. Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 5.

This case centers on the third of these pillars of Article XXIX: the scope of the

IECs jurisdiction when hearing complaints.

Based on the plain language of Article XXIX, the IEC has jurisdiction to

consider both advisory opinion requests and complaints that raise ethical issues

under the gift ban and revolving door provisions of Article XXIX, and under other

standards of conduct and reporting requirements found elsewhere in Colorado law.

Although Secretary Gesslers brief dismisses this half of the IECs

jurisdiction as a little-noticed phrase (Opening Br. at 9), the inclusion of pre-

existing standards of conduct known by (and binding upon) state and local officials

was a centerpiece of the newly-created IECs jurisdiction. The Bluebook used by

4

voters to explain Amendment 41 in the 2006 election explicitly referred to the

statutory Code of Ethics in C.R.S. 24-18-101 et seq. and stated that IEC

jurisdiction included violation of the proposal [amendment] or any other standard

of conduct or reporting requirement specified in law. See State of Colorado,

Legislative Council, Colorado General Assembly, Analysis of the 2006 Ballot

Proposals, at 9-10 (2006).

Colorado voters intended the IEC to enforce (and provide advice regarding)

the new gift ban, revolving door provisions, and existing statutory standards of

conduct such as the state Code of Ethics. This interpretation of the IECs

jurisdiction was the foundation of the Developmental Pathways challenge to the

gift ban provisions of Article XXIX, 3. See 178 P.3d at 534 (Plaintiffs sought to

have the gift bans of Amendment 41 rendered unconstitutional, leaving only the

provision creating the Commission, which, in their view, would then enforce

existing ethics laws.).

Enforcement actions at the IEC are initiated when any person files a

complaint asking whether a public officer, member of the general assembly, local

government official, or government employee has failed to comply with this article

or any other standards of conduct or reporting requirements as provided by law

within the preceding twelve months. Colo. Const., art. XXIX, 5(3)(a). The

amendment does not require that a complaining party be certain that a violation has

5

occurred. Rather, any person is entitled to file a complaint that asks the IEC to

determine whether a violation has occurred. The IEC is mandated to conduct an

investigation, hold a public hearing, and render findings on each non-frivolous

complaint pursuant to written rules adopted by the commission. Id. 5(3)(c). The

IEC may fine any covered person who breaches the public trust for private gain

double the amount of the financial equivalent of any benefits obtained by such

actions. Id. 6.

Under the constitutional scheme, a citizen asks whether an ethical standard

of conduct has been violated, and if not frivolous, the request is to be investigated

by the IEC. Nothing in Article XXIX or the IEC Rules handcuffs the IEC by

restricting its constitutionally-mandated investigation to legal theories specifically

cited in a complaint. Such a limitation would be inconsistent with Article XXIXs

command that the IEC investigate a complaint, not leave it to complaining parties

to dictate the course and scope of the inquiry. Indeed, the IECs procedural rules

sensibly leave it to the IEC to determine what ethics standards will be considered

at a hearing: The scope of the hearing shall be determined by the IEC and may be

limited to specific factual, ethical or legal issues. IEC Rule of Procedure 8.A.2., 8

C.C.R. 1510-1 (2011). This rule is well within the IECs constitutional authority

to prescribe written rules to govern the investigation and hearing, Colo. Const. art.

XXIX, 5(3)(c), and Secretary Gessler does not contend otherwise.

6

This was the process followed in this case when Ethics Watch submitted a

copy of its letter to the Denver District Attorney as an attachment to a complaint

asking the IEC to investigate and determine if ethical standards of conduct had

been broken. Additional public documents, provided in a supplement to that

complaint, were also considered in the IECs determination of whether the

complaint was frivolous under Article XXIX. After determining that the

complaint was not frivolous, the IEC spent months conducting an investigation

into the law and the facts applicable to the issues raised in the complaint. The IEC

also considered and decided a series of evidentiary and legal motions filed by

Secretary Gessler in the months leading up to the June 2013 hearing that relied

upon the same statutory standards of conduct as those argued at the final hearing.

B. The IEC Acted Well Within its Article XXIX Jurisdiction

The IECs final decision applied two longstanding statutory ethical

standards of conduct: the prohibition against breaching the public trust for private

gain contained in the Colorado Code of Ethics, C.R.S. 24-18-103(1), and the

statute creating discretionary funds for statewide elected officials, C.R.S. 24-9-

105. Despite Secretary Gesslers claims that these two statutes fall outside the

IECs jurisdiction as outlined in Article XXIX 5, these matters constitute the type

of conduct that is in violation of their public trust contemplated by Colorado

voters in Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 1.

7

The Colorado Supreme Court has made it clear that the IEC is entitled to the

deference normally accorded to administrative agencies when they interpret

statutes or regulations, even in its interpretation of Article XXIX itself. See

Developmental Pathways, 178 P.3d at 535. Agency interpretations of statutes they

administer are entitled to judicial deference if they are based upon a permissible

construction of the statute. North Colo. Medical Ctr., Inc. v. Committee on

Anticompetitive Conduct, 914 P.2d 902, 907 (Colo. 1996). The principle of

deference to administrative agencies fully applies when an agency acts in a judicial

or quasi-judicial capacity. See Sierra Club v. Billingsley, 166 P.3d 309, 312 (Colo.

App. 2007).

Moreover, the principle of deference to administrative agency interpretations

of its own statute applies to an agencys interpretation of the scope of its own

authority. See City of Arlington v. FCC, 133 S. Ct. 1863, 1868 (2013). The

question whether a complaint addresses an ethics issue arising under a standard

of conduct applicable to Article XXIX covered individuals is a quintessential

example of an agency's interpretation of a statute within its expertise that is is

entitled to deference if the statutes plain language is subject to different

reasonable interpretations. McCool v. Sears, 186 P.3d 147, 150 (Colo. App.

2008).

8

Under any standard, the two statutes considered by the IEC fit within the

definition of ethical issues arising any other standards of conduct . . . as provided

by law. Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 5(1). C.R.S. 24-18-103(1) is part of the state

Code of Ethics, which in turn is part of Article 18 of Title 24, C.R.S., entitled

Standards of Conduct. This is the same Code of Ethics referred to in the

Bluebook issued when voters adopted Article XXIX. The Code of Ethics mandates

that a public officer carry out his duties for the benefit of the people of the state,

C.R.S. 24-18-103(1), and provides a standard of conduct very similar to the

private sector requirement that an agent is subject to a duty to his principal to act

solely for the benefit of the principal in all matters connected with his agency. Jet

Courier Service, Inc. v. Mulei, 771 P.2d 486, 492 (Colo. 1989). That this standard

of conduct generally applies to every agent of the state in a wide variety of

circumstances does not make it any less a standard of conduct under the IECs

jurisdiction. It is not a surprise that ethics issues would arise from a breach of

public trust under C.R.S. 24-18-103(1).

Indeed, Article XXIX itself refers to enforcement matters alleging a breach

of public trust as within IEC jurisdiction when it directs a specific penalty of

double the amount at issue for an IEC finding of any breach of public trust for

private gain. Colo. Const. art. XXIX, 6. Ethics Watchs complaint alleged, and

the IEC found based on the evidence at the hearing, that Gessler breached the

9

public trust for private gain by converting public funds to personal and political

use. If actions alleging a breach of the public trust were outside the scope of the

IECs jurisdiction, the penalty provision of Article XXIX, 6 would be rendered

superfluous. See Colorado State Civil Service Emp. Ass'n v. Love, 448 P.2d 624,

630 (1968) (Each clause and sentence of either a constitution or statute must be

presumed to have purpose and use, which neither the courts nor the legislature may

ignore.).

The proper use of public funds is also the type of ethical issue arising

under statutory standards of conduct contemplated by Colorado voters and

within the plain language of Article XXIX. For almost 30 years, C.R.S. 24-9-105

has directed statewide elected officials use the allocated discretionary funds in

pursuance of official business as each elected official sees fit. Contrary to the

Secretarys argument, his discretion is not limitless: he could not, for example, use

his discretionary fund to contribute to political candidates or to pay himself a

personal bonus (as the evidence at the hearing proved he in fact did). He is directed

to use the money for official business; diverting the public funds entrusted to him

to political or personal use is a paradigm example of unethical conduct. The statute

provides ethical standards comfortably within the IECs jurisdiction.

Moreover, for additional specificity, the IEC correctly looked to the State

Fiscal Rules, which by their terms and the testimony of the State Controller apply

10

to the Secretary of State. See 1 C.C.R. 1-101 (2012). Doubtless, in a different

circumstance, a public official who complied with the Fiscal Rules would cry foul

if the IEC nevertheless found that he or she had used state funds improperly. The

question whether a violation of the State Fiscal Rules, without more, would be

subject to IEC jurisdiction is not presented by this case. Rather, the State Fiscal

Rules served here as a check on, and guidepost for, the IEC in fulfilling its role to

flesh out how the ethical standards of conduct existing in Colorado law applied to

Secretary Gesslers misuse of public funds entrusted to his care for personal and

partisan purposes.

It was a logical and permissible construction for the IEC to determine that a

statutory provision in the Code of Ethics (a preexisting set of standards of conduct

referred to in the Bluebook), or long-standing statutory provisions setting explicit

standards for the Secretary to follow when using public funds, were within the

agencys jurisdiction over ethical issues arising under standards of conduct

applicable to covered individuals. The agencys construction is plainly correct, or

at least, entitled to judicial deference. Developmental Pathways, 178 P.3d at 535.

C. There is No History of the IEC Improperly Expanding its Jurisdiction

Beyond the Authority in Article XXIX

As the Secretarys brief attempts to paint a picture of an out-of-control

power-grabbing agency, it boldly asserts that [t]he IEC has, literally, never found

a statute it did not find to be within its purview. (Opening Br. at 9). The actions of

11

the IEC over its seven-year history during which at all times it has been

represented by the Department of Law tell a different story.

As discussed above, enforcement matters proceed in two stages under

Article XXIX: first a discussion and determination by the IEC as to whether or not

the complaint is frivolous which is conducted in closed executive session, and

then the public hearings, investigation, deliberation and findings in open session

for complaints which pass that bar. Article XXIX mandates that complaints found

to be frivolous must be maintained confidential by the IEC. See Colo. Const. art.

XXIX, 5(3)(b). While the specific allegations and names of elected officials who

were the subject of those complaints deemed frivolous are not released, the IEC act

of finding a complaint frivolous is a matter of public record. The IEC chronicles on

its website all complaints it has received since 2008. Contrary to the Secretarys

assertions, a number of complaints have been dismissed on the grounds that the

IEC lacked jurisdiction over the matter alleged: 14 such complaints in 2014 alone.

3

Nor is there a historical record of abusive assertions of IEC jurisdiction in

the second category of complaints which are not found frivolous. Because the

IECs procedural rules place enormous burdens on a complaining party in an ethics

matter, few ethics complaints have survived to the hearing stage, much less a

decision and order for sanctions. In fact, this case represents the first decision of

3

Independent Ethics Commission, Complaints, available at

https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/iec/complaints (last accessed Oct. 23, 2014).

12

the IEC to impose penalties upon an elected official for ethics violations since the

IEC began operations in 2008.

In contrast to the Secretarys assertions, the IEC has repeatedly dismissed

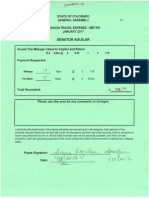

complaints for lack of jurisdiction. For example, the IEC dismissed Complaint 09-

04 against members of the Steamboat Springs School Board on the grounds that

the IEC lacks jurisdiction over unpaid members of boards and commissions and

employees of school boards. See April 8, 2009 letter in Complaint 09-04

(Attachment 1 hereto). The IEC reached this conclusion even though Colo. Const.

art. XXIX, 2(6) could be read to support the exercise of jurisdiction over school

board members by virtue of their status as elected officials. The constitutional

provision is ambiguous; the IECs resolution of this ambiguity through its

determination that it does not have jurisdiction over unpaid, elected school board

officials is within the scope of its delegated authority as administrator and enforcer

of Article XXIX. See Developmental Pathways, 178 P.3d at 535. The agency made

no attempt to stretch the limits of its constitutional jurisdiction.

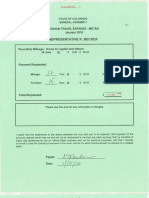

Another example of the IEC recognizing limits on its jurisdiction is the Final

Action in Complaint No. 09-08. After completing the investigation stage and

holding a full hearing in March 2010, the IEC issued factual findings and an

overall decision that there was no violation of Article XXIX or other applicable

standards of conduct. See Summary of Final Action in Complaint No. 09-08 (Fry

13

v. Burns) (April 19, 2010) (Attachment 2 hereto). Most relevant here, the IEC

specifically found that it did not have jurisdiction over alleged violations of

Colorados Open Meetings Law, C.R.S. 24-6-402. Attachment 2 at 7. Thus, the

Secretarys accusation that the IEC has never refused to claim jurisdiction over any

statutory basis for allegations is simply false.

This is not the first time the IEC has exercised jurisdiction over a complaint

presenting ethics questions arising out of standards of conduct other than the gift

ban and revolving door prohibition. Secretary Gesslers predecessor filed a

complaint in his official capacity asking whether an employee of the department

breached the public trust for private gain in violation of C.R.S. 24-18-108(2)(d)

and 24-50-117. See Final Order in Complaint No. 10-06 (Buescher v. Whitfield)

(Jan. 11, 2011) (Attachment 3 hereto). That matter was resolved with a stipulated

agreement by the parties including an admission by the employee that his conduct

violated these statutory standards of conduct.

Contrary to the Secretarys allegations, the IEC has a history of carefully

considering the scope of its jurisdiction under Article XXIX. The handling of this

case continues that track record and did not exceed the IECs constitutional

jurisdiction.

14

III. CONCLUSION

Considering the onerous burdens the IECs rules place on complaining

parties, it took a case this egregious to produce a decision actually fining a state

official for unethical conduct. Secretary Gesslers defiant use of state money to

fund his personal trip to his political partys national convention and a conference

of his partys lawyers, and his draining the year-end balance of his public funds

account to supplement his salary, is the type of breach of fiduciary duty and public

trust Colorado voters meant to stop through the passage of Amendment 41. The

evidence at the hearing established that Secretary Gessler breached the public trust

for private gain the sine qua non for the imposition of a penalty under Colo.

Const. art. XXIX, 6. The standards of conduct enforced in this matter were well

within the IECs jurisdiction. The Court should affirm the District Courts order

upholding the IECs findings and penalty.

DATED: October 27, 2014.

[Original Signature On File at

Colorado Ethics Watch]

/s/ Margaret Perl

Luis Toro, #22093

Margaret Perl, #43106

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

COLORADO ETHICS WATCH

15

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

I hereby certify that this brief complies with all requirements of C.A.R. 28

and C.A.R. 32, including all formatting requirements set forth in these rules.

Specifically, the undersigned certifies that:

The brief complies with C.A.R. 28(g). It contains 3,214 words in those

portions subject to the Rule.

By:__/s Margaret Perl_______________

Luis Toro, #22093

Margaret Perl, #43106

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

COLORADO ETHICS WATCH

16

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on October 27, 2014, I served a true and correct copy of

the foregoing BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-

APPELLEES via ICCES to the following:

Michael Francisco, Assistant Solicitor General

Kathryn A. Starnella, Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, State of Colorado

1300 Broadway, 10th Floor

Denver, CO 80203

Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant

Lisa Brenner Freimann, First Assistant Attorney General

Russell B. Klein, First Assistant Attorney General

Joel W. Kiesey, Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, State of Colorado

1300 Broadway, 8th Floor

Denver, Colorado 80203

Counsel for Defendants-Appellees

[Original Signature On File at

Colorado Ethics Watch]

/s/ Luis Toro

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- IEC Response Brief 12172013 Gessler v. GrossmanDocument47 pagesIEC Response Brief 12172013 Gessler v. GrossmanColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Amici Con - CCFDocument27 pagesAmici Con - CCFsmayer@howardrice.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Amendments 2010Document22 pagesConstitutional Amendments 2010Steve TerrellPas encore d'évaluation

- Dummett-Noonan V CA SOS - Petition For Cert. - US Supreme Court - 1/13/2015Document48 pagesDummett-Noonan V CA SOS - Petition For Cert. - US Supreme Court - 1/13/2015BirtherReportPas encore d'évaluation

- Klukowski-Making Executive Privilege Work-59 Cleveland St. L. Rev. 31 (2011)Document53 pagesKlukowski-Making Executive Privilege Work-59 Cleveland St. L. Rev. 31 (2011)Breitbart NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Trump V Biden Petition Appendix FinalDocument225 pagesTrump V Biden Petition Appendix FinalKrystal FrasierPas encore d'évaluation

- SEC v. CochranDocument18 pagesSEC v. CochranCato InstitutePas encore d'évaluation

- Day 1 - Poli + Comm - Digital Version SyllabusDocument139 pagesDay 1 - Poli + Comm - Digital Version SyllabusJennerLaennec SharlynJoy MattJayPas encore d'évaluation

- Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion For SummaryDocument20 pagesCuriae in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion For SummaryCatherine SnowPas encore d'évaluation

- Maryland Open Meetings Act Manual CompleteDocument97 pagesMaryland Open Meetings Act Manual CompleteCraig O'DonnellPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 47 OUIDocument43 pagesCH 47 OUIloomcPas encore d'évaluation

- Rey LacaDocument134 pagesRey LacaRey LacadenPas encore d'évaluation

- Gohmert V Pence - Mémoire Chambre Représentants 31 Dec 2020Document26 pagesGohmert V Pence - Mémoire Chambre Représentants 31 Dec 2020Pascal MbongoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ruling - Standing - Cerame v. BowlerDocument25 pagesRuling - Standing - Cerame v. BowleremploymentlawyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Matthew Seligman Report: Analysis of Lawfulness of Chesebro Elector Plan Under Federal Election Law Just Security October 9 2023Document62 pagesMatthew Seligman Report: Analysis of Lawfulness of Chesebro Elector Plan Under Federal Election Law Just Security October 9 2023Just Security100% (1)

- Scott Gessler Appeal of Ethics Commission Sanctions - Opening BriefDocument56 pagesScott Gessler Appeal of Ethics Commission Sanctions - Opening BriefColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Court of Criminal Appeals: PetitionerDocument17 pagesIn The Court of Criminal Appeals: PetitionerHayden SparksPas encore d'évaluation

- Intervener Factum Access Copyright and Copibec, CCH Case Supreme Court of CanadaDocument25 pagesIntervener Factum Access Copyright and Copibec, CCH Case Supreme Court of CanadaAriel KatzPas encore d'évaluation

- Maryland Open Meetings Act Manual CompleteDocument97 pagesMaryland Open Meetings Act Manual CompleteCraig O'DonnellPas encore d'évaluation

- Manhattan Community Access Corporation v. HalleckDocument25 pagesManhattan Community Access Corporation v. HalleckCato InstitutePas encore d'évaluation

- Customary Law Without CustomDocument37 pagesCustomary Law Without CustomhenfaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Bill To Provide Protection For Fashion Design: HearingDocument226 pagesA Bill To Provide Protection For Fashion Design: HearingScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Rev. Fr. Emmanuel Lemelson Files Writ of Certiorari With US Supreme Court in Unprecedented 9-Year SEC FightDocument103 pagesRev. Fr. Emmanuel Lemelson Files Writ of Certiorari With US Supreme Court in Unprecedented 9-Year SEC FightamvonaPas encore d'évaluation

- Judge Says Multiple Parts of NY's New Gun Licensing, Carrying Rules Are UnconstitutionalDocument53 pagesJudge Says Multiple Parts of NY's New Gun Licensing, Carrying Rules Are UnconstitutionalJana BarnelloPas encore d'évaluation

- Petition For Writ of Certiorari, Bohon v. Fed. Energy Reg. Comm'n, No. 22-256 (Sep. 19, 2022)Document34 pagesPetition For Writ of Certiorari, Bohon v. Fed. Energy Reg. Comm'n, No. 22-256 (Sep. 19, 2022)RHTPas encore d'évaluation

- VA V Sebelius Marshall Amicus Brief of Gun Owners of America Et AlDocument42 pagesVA V Sebelius Marshall Amicus Brief of Gun Owners of America Et AlAssociation of American Physicians and SurgeonsPas encore d'évaluation

- National Law University Odisha, Cuttack: Conveniens in Conflict of LawsDocument18 pagesNational Law University Odisha, Cuttack: Conveniens in Conflict of LawsdhawalPas encore d'évaluation

- Citizens United & Citizens United Foundation File Amicus Brief in Carpenter v. United StatesDocument44 pagesCitizens United & Citizens United Foundation File Amicus Brief in Carpenter v. United StatesCitizens UnitedPas encore d'évaluation

- COMMONWEALTH of VIRGINIA - 31.1 - Attachments: # 1 Proposed Amici Brief - Gov - Uscourts.vaed.252045.31.1Document32 pagesCOMMONWEALTH of VIRGINIA - 31.1 - Attachments: # 1 Proposed Amici Brief - Gov - Uscourts.vaed.252045.31.1Jack RyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Group No 2 Civil Procedure I MuDocument19 pagesGroup No 2 Civil Procedure I MuIbrahim SaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Bureau of Prisons Update 2011 Oregon Federal DefenderDocument40 pagesBureau of Prisons Update 2011 Oregon Federal Defendermary engPas encore d'évaluation

- Aguirre Severson Lawsuit Against CPUCDocument33 pagesAguirre Severson Lawsuit Against CPUCRob NikolewskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Judicialreview of Legislation in Sri Lankan ContextDocument14 pagesJudicialreview of Legislation in Sri Lankan Contextnayanajithishara706Pas encore d'évaluation

- Curtis Brooks: Amended Amicus BriefDocument14 pagesCurtis Brooks: Amended Amicus BriefMichael_Lee_RobertsPas encore d'évaluation

- Schulz V US Congress USCA DCC 21-5164 Appellate BriefDocument60 pagesSchulz V US Congress USCA DCC 21-5164 Appellate BriefHarold Van AllenPas encore d'évaluation

- CU, CUF, TPC Amicus Brief - U.S. v. Texas (Biden Admin - Illegal Immigration)Document40 pagesCU, CUF, TPC Amicus Brief - U.S. v. Texas (Biden Admin - Illegal Immigration)Citizens UnitedPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Supreme Court of The United States: PetitionersDocument26 pagesIn The Supreme Court of The United States: PetitionersHannah Hill100% (3)

- U.S. v. Esquenazi (Amicus Brief of Professor Michael Koehler)Document32 pagesU.S. v. Esquenazi (Amicus Brief of Professor Michael Koehler)Mike KoehlerPas encore d'évaluation

- Rules of Presumption and Statutory Inerpretation Form InstructionsDocument24 pagesRules of Presumption and Statutory Inerpretation Form InstructionsJesse Faulkner100% (1)

- Appellants' Filed Brief in Re Brosemer, Et Al.Document29 pagesAppellants' Filed Brief in Re Brosemer, Et Al.Kayode CrownPas encore d'évaluation

- IVAN ANTONYUK COREY JOHNSON ALFRED TERRILLE JOSEPH MANN LESLIE LEMAN and LAWRENCE SLOANE V. NEW YORK STATEDocument53 pagesIVAN ANTONYUK COREY JOHNSON ALFRED TERRILLE JOSEPH MANN LESLIE LEMAN and LAWRENCE SLOANE V. NEW YORK STATEJillian SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- C.R.P. 292 2021 Sacked EmployeesDocument31 pagesC.R.P. 292 2021 Sacked EmployeesSyed AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- The History of The Child Pornography GuidelinesDocument57 pagesThe History of The Child Pornography GuidelinesMarsh Law Firm PLLC0% (2)

- Public Access, Sealing & Expungement of District Court RecordsDocument55 pagesPublic Access, Sealing & Expungement of District Court RecordsloomcPas encore d'évaluation

- SAF Welcomes NRA Motion To Join in Its Lawsuit v. ATFDocument26 pagesSAF Welcomes NRA Motion To Join in Its Lawsuit v. ATFAmmoLand Shooting Sports NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020-11-24 Reply Iso Fed Def MSJDocument19 pages2020-11-24 Reply Iso Fed Def MSJRicca PrasadPas encore d'évaluation

- Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion For SummaryDocument17 pagesCuriae in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion For SummaryIan MillhiserPas encore d'évaluation

- Law Prof Metlife Brief 6.23.2016Document45 pagesLaw Prof Metlife Brief 6.23.2016Chris WalkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Perry v. Perez, Cato Legal BriefsDocument41 pagesPerry v. Perez, Cato Legal BriefsCato InstitutePas encore d'évaluation

- Tumpson v. Farina - Reply To Amici Before NJ Supreme Court - NJ Appleseed PILCDocument17 pagesTumpson v. Farina - Reply To Amici Before NJ Supreme Court - NJ Appleseed PILCFlavio KomuvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Billups v. City of CharlestonDocument18 pagesBillups v. City of CharlestonCato InstitutePas encore d'évaluation

- Bixler V Scientology: Petition For RehearingDocument45 pagesBixler V Scientology: Petition For RehearingTony OrtegaPas encore d'évaluation

- DOJ/Pence Reply To GohmertDocument14 pagesDOJ/Pence Reply To GohmertRebecca Harrington100% (1)

- The Future of Federal HiringDocument47 pagesThe Future of Federal HiringNicolas LoyolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti I LoanzonDocument51 pagesConsti I LoanzonPbftPas encore d'évaluation

- 21-04-09 Amicus Brief Walter CopanDocument30 pages21-04-09 Amicus Brief Walter CopanFlorian MuellerPas encore d'évaluation

- TCreplyDocument8 pagesTCreplyCircuit MediaPas encore d'évaluation

- Guruswamy Menaka, Aditya Singh - Accessing Injustice - Gram Nyayalayas Act 2008Document4 pagesGuruswamy Menaka, Aditya Singh - Accessing Injustice - Gram Nyayalayas Act 2008Ajeet_1991Pas encore d'évaluation

- Packages of Judicial Independence: The Selection and Tenure of Article III JudgesDocument44 pagesPackages of Judicial Independence: The Selection and Tenure of Article III JudgeslawclcPas encore d'évaluation

- Freedom of Speech for Members of Parliament in TanzaniaD'EverandFreedom of Speech for Members of Parliament in TanzaniaÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Oct 2017 Comment On CPF RulemakingDocument2 pagesOct 2017 Comment On CPF RulemakingColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 2 of 6Document95 pages2017 Coleg Per Diem 2 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 6 of 6Document114 pages2017 Coleg Per Diem 6 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- LT Governor Donna Lynne Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Document95 pagesLT Governor Donna Lynne Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- IEC Draft Position Statement On Frivolous DeterminationsDocument2 pagesIEC Draft Position Statement On Frivolous DeterminationsColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 1 of 6Document122 pages2017 Coleg Per Diem 1 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 3 of 6Document93 pages2017 Coleg Per Diem 3 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Attorney General Cynthia Coffman Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Document13 pagesAttorney General Cynthia Coffman Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 5 of 6Document76 pages2017 Coleg Per Diem 5 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Coleg Per Diem 4 of 6Document108 pages2017 Coleg Per Diem 4 of 6Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Treasurer Stapleton Calendar Feb-Apr 2017Document13 pagesTreasurer Stapleton Calendar Feb-Apr 2017Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Governor Hickenlooper Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Document155 pagesGovernor Hickenlooper Calendar Jan-Mar 2017Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- SoS Wayne Williams Jun-Aug 2016 CalendarDocument92 pagesSoS Wayne Williams Jun-Aug 2016 CalendarColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Treasurer Stapleton Calendar Nov 1 2016-Jan 31 2017Document14 pagesTreasurer Stapleton Calendar Nov 1 2016-Jan 31 2017Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- SoS Wayne Williams Calendar Dec 2016-Feb 2017Document14 pagesSoS Wayne Williams Calendar Dec 2016-Feb 2017Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem and Mileage Part 3Document100 pages2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem and Mileage Part 3Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Electioneering Gap ReportDocument1 pageElectioneering Gap ReportColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Hickenlooper Calendar Oct-Dec 2016Document155 pagesHickenlooper Calendar Oct-Dec 2016Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage 2016 Part 5Document95 pages2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage 2016 Part 5Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Hickenlooper Calendar Jul-Sep 2016Document132 pagesHickenlooper Calendar Jul-Sep 2016Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Treasurer Stapleton Calendar May-July 2016Document14 pagesTreasurer Stapleton Calendar May-July 2016Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Treasurer Stapleton Calendar 8.1.2016-10.31.2016Document14 pagesTreasurer Stapleton Calendar 8.1.2016-10.31.2016Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Re: Draft Position Statement Regarding Home Rule Municipalities Ethics CodesDocument10 pagesRe: Draft Position Statement Regarding Home Rule Municipalities Ethics CodesColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 4Document96 pages2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 4Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics Watch Comment On July 26 CPF RulemakingDocument8 pagesEthics Watch Comment On July 26 CPF RulemakingColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 2Document164 pages2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 2Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Hickenlooper Calendar Apr-Jun 2016Document1 pageHickenlooper Calendar Apr-Jun 2016Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 1Document130 pages2016 Colorado General Assembly Per Diem & Mileage Part 1Colorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- CO Ethics Watch 2016session3 Part I PDFDocument100 pagesCO Ethics Watch 2016session3 Part I PDFColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Crowley County Ethics PolicyDocument2 pagesCrowley County Ethics PolicyColorado Ethics WatchPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs Ritter (1991) DECISIONDocument7 pagesPeople vs Ritter (1991) DECISIONVirnadette LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- 8-10-17-Final - Orlando Et Al. v. Corporate BailoutsDocument30 pages8-10-17-Final - Orlando Et Al. v. Corporate BailoutsNew York PostPas encore d'évaluation

- PNB V. Se, Et Al.: 18 April 1996 G.R. No. 119231 Hermosisima, JR., J.: Special Laws - Warehouse Receipts LawDocument3 pagesPNB V. Se, Et Al.: 18 April 1996 G.R. No. 119231 Hermosisima, JR., J.: Special Laws - Warehouse Receipts LawKelvin ZabatPas encore d'évaluation

- Colent - OppositionDocument7 pagesColent - OppositionILANIE MALINISPas encore d'évaluation

- Ricarze vs. Court of Appeals, 515 SCRA 302, G.R. No. 160451 February 9, 2007Document22 pagesRicarze vs. Court of Appeals, 515 SCRA 302, G.R. No. 160451 February 9, 2007Lester AgoncilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Ebarle v. Sucaldito: Is EO 264 Applicable in Criminal CasesDocument4 pagesEbarle v. Sucaldito: Is EO 264 Applicable in Criminal CasesAyla CristobalPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit ABADocument2 pagesAffidavit ABAMitch Tuazon100% (1)

- Bernard Klimek and Deborah Klimek v. Horace Mann Insurance Co., 14 F.3d 185, 2d Cir. (1994)Document7 pagesBernard Klimek and Deborah Klimek v. Horace Mann Insurance Co., 14 F.3d 185, 2d Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership Liquidation 1Document18 pagesPartnership Liquidation 1illustra7Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philcontrust Resources IncDocument7 pagesPhilcontrust Resources Incjun junPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal and Regulatory Environment of BusinessDocument299 pagesLegal and Regulatory Environment of BusinessDipanshu GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- The High Court's Landmark Decision On The Constitutional Validity of Same-Sex Marriage in AustraliaDocument5 pagesThe High Court's Landmark Decision On The Constitutional Validity of Same-Sex Marriage in AustraliaCorey GauciPas encore d'évaluation

- Madras Hindu Religious Endowments Act AmendedDocument19 pagesMadras Hindu Religious Endowments Act Amendedneet1Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Extinctive Effect of Promossory EstoppelDocument9 pagesThe Extinctive Effect of Promossory EstoppelSiu Chen LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Barangay LawsDocument8 pagesBarangay LawsEvan Carlos PingolPas encore d'évaluation

- The North Borneo QuestionDocument11 pagesThe North Borneo QuestionSteve B. Salonga100% (1)

- Marriage and FamilyDocument4 pagesMarriage and FamilyJenny Pasilan QuintanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Ethics 9Document1 pageLegal Ethics 9lhemnavalPas encore d'évaluation

- Heirs' Co-Ownership of Leasehold Rights UpheldDocument7 pagesHeirs' Co-Ownership of Leasehold Rights UpheldSittenor AbdulPas encore d'évaluation

- Yucapia V Lantern Proposed SACDocument37 pagesYucapia V Lantern Proposed SACTHROnline100% (1)

- In The Matter of Francesco Paolo La Franca v. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 413 F.2d 686, 2d Cir. (1969)Document6 pagesIn The Matter of Francesco Paolo La Franca v. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 413 F.2d 686, 2d Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- #European V Ingenieuburo BirkhahnDocument2 pages#European V Ingenieuburo BirkhahnKareen BaucanPas encore d'évaluation

- When Bad Things Happen To Good LawyersDocument77 pagesWhen Bad Things Happen To Good LawyersZeeshan IlyasPas encore d'évaluation

- (HC) Todd Anthony Andrade v. James Yates - Document No. 5Document4 pages(HC) Todd Anthony Andrade v. James Yates - Document No. 5Justia.com100% (1)

- Tan v. Valeriano: Malicious Prosecution Case DismissedDocument3 pagesTan v. Valeriano: Malicious Prosecution Case DismissedJulia Camille RealPas encore d'évaluation

- R D Saxena Vs Balram Prasad SharmaDocument2 pagesR D Saxena Vs Balram Prasad SharmaR.k.p SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Trump vs. TwitterDocument13 pagesTrump vs. Twitterjonathan_skillingsPas encore d'évaluation

- Dowry Harassment Case AppealDocument2 pagesDowry Harassment Case AppealPiyushPas encore d'évaluation

- Jose Emilio Alvarado A208 090 238 (BIA June 2, 2016)Document3 pagesJose Emilio Alvarado A208 090 238 (BIA June 2, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- Velasquez Vs HernandezDocument6 pagesVelasquez Vs HernandezRalph Mark Joseph100% (1)