Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

SSRN Id1583348 Libre

Transféré par

Harjot SinghCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SSRN Id1583348 Libre

Transféré par

Harjot SinghDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.

com/abstract=1583348

1

Sources of International Human Rights and Their Application in the United States

First draft of the first chapter of the Master thesis

Protecting Human Rights Preserves National Security

Michele Maria Porcelluzzi

Si vis pacem, para bellum. If you want peace, prepare for war.

This ancient Roman proverb would no longer be true in a world in which the nations have

recognized the existence of human rights and in which individuals are informed about

what is happening across the world. This ideal world is one which does not consider war

as an expression of human nature or a tool to make money or to settle international

conflicts, butin light of the U.N. Charter

1

as an instrument to defend a country

threatened or attacked by another.

However, the war on terror, fought not by some countries against other

countries but rather by a coalition of many countries against non-state actors, challenges

the post-World War II norms which establish the respect of human rights. Is torture

morally and legally justifiable in some cases? What is the relationship between human

rights and international law? Is international law accurately applied by U.S. courts? Can

the human rights be considered jus cogens? Is it possible to be less free but more safe?

This paper considers the sources of international human rights law and their

application by American courts. Based on the recent decisions of different courts and the

Restatement (third) of U.S. Foreign Relations law

2

, the paper explains how judges apply

treaties and consider the customary law as federal common law. Concerning jus cogens,

J.D. Candidate 2010, Bocconi Law School- Milan, Exchange Student at Duke Law School in Fall 2009. For

their indication of sources, comments and suggestions I thank Prof. Samantha Besson and Prof. Scott

Silliman. This is the first part of my Master degree thesis, my supervisor is Giorgio Sacerdoti, Full Professor

in International Law, Bocconi Law School- Milan. I thank Virginia Franks and David Chiang -Duke Law

students- for their review. I thank also Nicole Yong and Matt Smith .

1

See U.N. Charters, art. 2(4) and 51

2

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF THE FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1583348

2

the paper reports the conflicting opinions of some scholars and argues that few

preemptive norms exist or should be applied by courts. The conclusion reports the

opinions of the author about the purpose of international law in the third millennium and

the new challenge to human rights.

3

Human Rights as International Law, and International Law as the Law of the

United States

[We are] unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to

which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at

home and around the world.--John F. Kennedy

3

The term international human rights law refers to that area of international law

concerned with the protection of human rights. The sources of international human rights

are the same as of international law settled by Article 38 of the Statute of the ICJ:

international conventions, whether general or particular, establishing rules expressly

recognized by the contesting states;

international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law;

the general principles of law recognized by civilized nations;

subject to the provisions of Article 59, judicial decisions and the teachings of the most

highly qualified publicists of the various nations, as subsidiary means for the

determination of rules of law.

This chapter analyzes the main sources and how they are applied by U.S. Courts.

Part I -The Treaties

Section 1: International Law

The most important sources for international human rights are the treaties. After

the Second World War and the founding of the United Nations, the production of

multilateral treaties for the protection of specifically enumerated human rights has

increased. In the last sixty years, leaders have elaborated upon and approved numerous

texts concerning human rights, but not all of these are binding for the United States.

For example, the U.N. Charter contain some human rights provisions that do not

require legal obligations on the part of the member states. In particular, Article 55(c) and

56 state that the United Nations shall promote the universal respect, and observance of,

3

Inaugural address, 20 January 1961

4

human rights and that [a]ll members pledge themselves to take joint and separate

action in cooperation with the Organization for the achievement of the purposes set forth

in Article 55. Traditionally, scholars consider these provisions not binding for the

Member State: they are guiding principles or general purposes, or indeed legally

meaningless and redundant

4

.

Likewise, the Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the General Assembly on

December 10, 1948, is not binding because only the resolutions of the Security Council

may involve legal obligations on the part of the States. However, the Declaration has

served as the foundation for many treaties, and numerous scholars consider it to be a

central component of international customary law which may be invoked under

appropriate circumstances by federal and other judiciaries.

Now, in October 2009, there are two binding international bills of human rights

and nine core international rights treaties

5

. These international agreements involve legal

obligations on the part of member states:

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966;

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966;

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial

Discrimination, 1965

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 International Covenant

on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women,

1979

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or

Punishment, 1984

Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989

International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers

and Members of Their Families, 1990

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced

4

See Oschar Schachter, The Charter and the Constitution: The Human Rights provisions in American Law,

4 Vand. L. Rev. 643, 646

5

So defined by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Source:

http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/index.htm

5

Disappearance, 2006

Section 2- The U.S. Law

The Constitution of the United States establishes the process for making treaties

and whether they are binding in nature. The President shall have power, by and with the

advice and consent of the Senate, to make treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators

present concur

6

; The judicial power shall extend to all cases arising under the treaties

made

7

; All treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United

States, shall be the supreme law of the land

8

. The intention of the Framers is clear:

when ratified the treaties become obligatory and the assent of the House of

Representatives is not necessary

9

; early decisions followed this path

10

. However, in

1829 Chief Justice Marshall wrote that if a treaty is carried into execution whenever it

operates of itself

11

, then some treaties do not operate of themselves and need a domestic

law or other exercises of sovereign power to carry out their execution. In that case,

Marshall found that the terms shall be ratified and confirmed, inserted in the Treaty of

Amity signed in 1818 by United States and Spain implied that a part of it had no direct

effect. Marshall arrived at this decision through the analysis of the text of the Treaty

12

.

The analysis of two recent decisions could be useful to clarify the criterion now

used by American judges in order to determine the self-executing character of the treaties

and their relationship with legislative acts of the Congress. The first is Committee of U.S.

6

U.S. Cons. art. II 2

7

Id. art. III 2 cl.1

8

Id. art. VI cl.2

9

President George Washington, Message to the House of Representatives, March, 30, 1796, reprinted in

3 THE RECORDS OF THE FEDERAL CONVENTION OF 1787, at 371 ( M. Farrand ed. 1937)

10

See, each other, Hamilton v. Eaton 11 F. Cas. 336, 340 (C.C.D.N.C. 1792) (No, 5,980), Penhallow v.

uoanes Admln., 3 u.. (3 uall.) 34, 94 (1793).

11

Foster v. Neilson, 27 U.S. (2 Pet.) 253, 314 (1829)

12

See JORDAN J. PAUST, International Law as Law of the United States, 70-73, (Second edition Carolina

Accademic Press, 2003) (1996)

6

Citizens Living in Nigaragua v. Reagan

13

, a case decided by the Court of Appeals of D.C.

Circuit in 1988.

In 1986 the International Court of Justice found that United States violated

international law by financing Contra guerrillas in their war against the Nicaraguan

government and by mining Nicaragua's harbors. The United States, however, ignored the

verdict, refused to pay the damages to Nicaragua and continued to finance military

operation in that country. US Ambassador to the UN, Jeanne Kirkpatrick said of the ICJ,

This is a semi-legal, semi-juridical, semi-political body which nations sometimes accept

and sometimes don't

14

.

Plaintiffs, organizations and individuals, showed that the President, financing the

Contras, violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), the United States

Constitution, the U.N. Charter and customary international law. The court dismissed the

case because so much of appellants' cause of action is based on international law

15

and

thus the congressional enactments cannot violate but can only supersede prior

inconsistent treaties or customary norms of international law

16

. The court dismissed

also the Fifth Amendment claims, because appellants' factual averments concerning the

Contras' injuries to Americans in Nicaragua cannot support a constitutional claim

against the United States for its support of that foreign "resistance" movement

17

.

Regarding the effects of international law on domestic law, the court held that the

violations of international law have no domestic consequences when the President and

13

859 F.2d 929 (D.C. Cir., 1988)

14

DON MURRAY, Genocide and the muddle that is international law, CBC News on-line. See

http://www.cbc.ca/news/reportsfromabroad/murray/20070227.html

15

Note 13, at 953

16

Supra

17

Supra

7

the Congress act together. The judges found that even if the two political branches

contravene an international legal norm, the court cannot remedy the violation, if the type

of international obligation that Congress and the President violate is either a treaty or a

rule of customary law.

18

So, while in the American Citizen case the Congress did not

make clear its intent to abrogate Article 94

19

of the UN Charter, the Court held that it

will not lightly infer such intent but will strive to harmonize the conflicting

enactments

20

.

In regard to the self-executing character of the UN Charter, the court, citing the

Diggs

21

case, noted that it look[ed] to the intent of the signatory parties as manifested by

the language of the instrument.

22

Then the Court found that the U.N. Charter does not

confer rights on private individuals, who cannot be parties in front on the ICJ, and that

Article 94 is not addressed to the judicial branch of the United States. The judges also

cited Article 59 of the Statue of the International Court of justice, which established that

[t]he decision of the Court has no binding force except between the parties and in

respect of that particular case.

23

Concerning the hierarchy of authority, that is the relation between the treaties and

the statutes of the Congress, the court applied the principle lex posterior derogat legi

priori . Supporting this opinion the court cited the Head Money Cases

24

, ruling that a

treaty is subject to such acts as Congress may pass for its enforcement, modification, or

18

See note 13 at 935

19

Each Member of the United Nations undertakes to comply with the decision of the International Court of

Justice in any case to which it is a party

20

Note 13 at 936

21

Diggs v. Shultz, 470 F.2d 461 (D.C. Cir., 1972)

22

Supra, 466

23

Note 13 at 938

24

112 U.S. 580 (1884)

8

repeal

25

.

The decision Medellin v. Texas

26

is analogous in some important aspects. On

January 9, 2003, Mexico filed a suit in the International Court of Justice against United

States alleging that the United States, in arresting, detaining, trying, convicting, and

sentencing the 54 Mexican nationals on death row () violated its international legal

obligations to Mexico, in its own right and in the exercise or its right of consular

protection of its nationals, as provided by Articles 5 and 36, respectively of the Vienna

Convention.

27

Unanimously, the judges held that the United States of America should

provide review and reconsideration of the conviction and sentence.

28

On February 28, 2005, President George W. Bush issued a memorandum to the

United States Attorney General ordering the state court to consider the complaints of the

Mexican prisoners, in accordance with the decision of the ICJ

29

. The Plaintiff, one of the

51 Mexican prisoners expressly named in the ICJ decision, filed an application for a writ

of habeas corpus in the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, which the Texas Court

subsequently dismissed.

The Supreme Court affirmed the judgment of the state court. In contradiction to

the U.N. Charter (a treaty signed and ratified by the U.S), the ICJ statute, the ICJ

pronouncement and the Memorandum of the President of the United States, the court held

that the ICJ decision is not self-executing. As in the Foster case, the criterion used by the

court for this pronouncement is its analysis of the text of the treaty. The Court found that,

25

Supra at 599

26

128 S. Ct. 1346 (2008)

27

Case concerning Avena and Other Mexican Nationals (Mexico v. U.SA..) 2004 I.C.J. 12 at 11 (March 31),

See also the application of Mexico

28

See Supra at 72

29

See Memorandum of the President of the U.S. for the Attorney General, February, 28 2005

9

in order to be self-executing, it should indicate that the President and Senate intended

for the agreement to have domestic effect

30

. In order to support this opinion, the court

cited United States Citizens and Head Money Cases.

In the judgment the United States argued that even if the ICJ decision is not self-

executing, it becomes law of the land by reason of the issuing of the Memorandum of the

President. Further, the government retained that the President, according to the

Youngstown

31

decision, had an implicit power in order to comply with the ICJ decision,

created by the ratification of the Optional Protocol of Vienna Convention on Consular

Relation

32

and the U.N. Charter. The court instead held that the President cannot

transform a non-self-executing international obligation into a self-executing one: he

needs the approval of the Congress, which can implement a non-self-executing treaty

33

.

The Supreme Court too strictly applies the dualistic principle; decision by

decision, the Court has deformed the Constitutional provision. In Medellin v. Texas the

Court held that a Treaty is self-executing only when a clear statement contained in the

text of the treaty or approved by the two thirds majority of the Senate and the President

indicates so. However, in the Foster decision the terms were inverted: Judge Marshall

found that only when the text of the treaty implied an implementation is it non-self-

executing. Yet this much older decision appears more in compliance with the

Constitution provision and the will of the Framers; in fact, if only few treaties have

domestic effect, why does the Constitution require not only the signature of the President

but also the approval of the Senate with a large majority (two-thirds)? What is the value

30

Note 27 at 1364

31

343 U.S., at 635,72 S. Ct. 863, 96 L. Ed. 1153, 62 Ohio Law Abs. 417 (Jackson, J., concurring)

32

Which establish the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ for the resolution of disputes arising out the

application of the Vienna Convention

33

Note 27, at 1368-1369

10

of this authorization if the treaties are applicable by the courts only if there is a clear

statement? Justice Breyer

34

was right in his dissenting opinion in Medellin, where he

maintains that hardly any international agreement contains a clear statement about its

self-execution. Thus I think that it is necessarily an elastic dualistic system: respecting

the sovereignty of the United States, and in compliance with the Constitutional provisions

all and only the treaties signed by the President, approved by the two thirds majority of

the Senate, not containing a clear statement about an implementation by the Congress are

law of the land.

However, the two cases analyzed are different in one important aspect. In the U.S.

Citizen case the plaintiffs were not cited in the ICJ decision, they were involved only

physically in the acts of the Congress which financed the Contras only because they

lived there, but were neither parts nor objects of the ICJ judgment. Oppositely, Jos

Ernesto Medellin was one of the 51 Mexican prisoners expressly mentioned in the

decision; of course he is not a part in the ICJ judgment, because only the state can be

part in a judgment of ICJ, but he is the object of the decision. Thus it was reasonable

that the state court or the Supreme Court applied the Avena decision.

Regarding the rank of the treaties: all of them are not similar to the domestic

legislative acts, and sometimes the last in time rule should not be applied. Some

treaties, like those which enumerate a human right or the U.N. Charter, are more

important than, for example, an international commercial agreement. If a self-executing

treaty that obligates the U.S. to respect a particular human right could not prevail against

an ordinary law which violates this right, what would be its utility? In this case there

would be, surely, a violation of international law but what about the remedies in foro

34

Note 27 at 1383

11

domestico? However, if the ratification of a treaty establishing a right could not be

modified or abrogated by the Congress, the U.S. would lose a part of its sovereignty.

Paust

35

suggests a solution to this dilemma citing two very old decisions; in

Holden v. Joy

36

, Justice Clifford wrote, Congress has no constitutional power to settle

or interfere with the rights under a treaties, except in cases purely political.

37

In 1899,

Justice Gray, supporting the Jones v. Meehan

38

courts decision wrote, The construction

of treaties is the peculiar province of the judiciary; and, except in cases purely political,

Congress has no Constitutional power to settle the rights under a treaty, or to affect titles

already granted by the treaty itself.

39

Thus it seems that Congress can modify,

reinterpret or repeal a treaty granting a human right only for political causes which the

Courts can verify.

Part 2 The Custom

Section 1- The Human Rights and the International Customary Law

From reading the international law textbooks and numerous articles about

international customary law, a student can compare it to two human sentiments: love and

friendship. Everyone knows what these important components of life are; however, few

people can explain what love or friendship mean, and the opinions expressed often are

opposite. Similarly, the scholars recognize that custom is a source of international law, in

compliance with Article 38 of the Statute of the ICJ, but there are many different

opinions about the elements required and the exact provisions. This part explains the

opinions of the main academic commentators in order to clarify the differences between

35

Note 12 at 74

36

84,U.S. (17 Wall.) (Sup. Court, 1872)

37

Idem at 211

38

175 U.S. 1 (Sup. Court, 1899)

39

Idem, at 32

12

them. Further, this part attempts to answer the question Are the human rights part of the

international customary law?.

The definition of customary lawgeneral practice accepted as law

40

traditionally includes the two elements: the general practice (an objective element) and

the opinion juris sive necessitates (the subjective element), that is the appearance that

the states follow the practice from a sense of legal obligation.

41

Before the Second

World War, the rules recognized as customary law were few, and they concerned only the

relations between the states (for example, the immunity of foreign states and their

diplomatic agents, the prohibition of piracy, etc.).

However some scholars do not accept this definition. Kelsen and Gugennheim in

the first half of the twentieth century tried to dispense with the objective element,

theorizing that customary international law arises from state practice alone.

42

Then they

look to the past, identify the State behavior and then, in an inductive process, they infer

what the norms are.

The post-World War II era, the creation of the UN, and the sentiment that human

rights needed to be protected not only with treaties (which for some scholars are

insufficient), have led to the creation of new theories for international customary law, in

order to identify human rights as custom.

Numerous academic commentators

43

, for different reasons, maintain that the 1948

40

Statue of the ICJ, art. 38

41

Note 2, 102 (n)

42

Kelsen H, Theorie du droit International coutumier (1939) 1 Revue international de la thorie du droit,

Nouvelle Srie 253 ; Guggenheim P, Les deux elements de la coutume en droit international, in La

technique et les principles du droit public: Etudes en lhonneur de Georges Scelle (1950), Vol 1, p. 275

43

See e.g. Humphrey JP, "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Its History, Impact and Juridical

Character", in Ramcharan BG (ed), Human Rights: Thirty Years After the Universal Declaration (1979)

pp2l, 37; Sohn 1, "The Human Rights Law of the Charter" (1977) 12 Texas Int LJ 129, 133 ;McDougal MS,

Lasswell H and Chen I, Human Rights and World Public Order (1980) pp273-274, 325-327; D'Amato A,

13

Universal Declaration of Human Rights is now part of international customary law. In

particular, Paust

44

argues that the term general practice does not refer only to the

States behavior, but to the practice of all participants in the international legal process,

including the international organizations. Regarding the opinion iuris, he affirms it is not

important that the States or their officials feel a sense of legal obligation related to a

practice, but he wrote that the subjective element is to be gathered from patterns of

generally shared legal expectation among the humanity.

45

Applying this rule, he affirmed that the resolutions approved by the General

Assembly of the UN can be sources of customary law, almost comparing this UN organ

to a world parliament which voices the opinions of the people. Although this world

democracy would be a beautiful image, it is not the reality: the General Assembly does

not represent the people, but rather the government, of most of the member nations.

Regarding his definitions of opinion iuris and state practice, they depart too far from the

traditional meanings to carry much weight.

According to other views, only some human rights obligations exist as customary

law. Schachter

46

, for example, analyzes the UN resolutions and declarations, finding

numerous references to duties arising out of the Universal Declaration and some

national constitutions, finding that many of them contain human rights provisions and

some embody ICJ decisions.

47

Then Schacter considers that the infringements of some

human rights are generally tolerated by the international community. The author, then,

International Law: Process and Prospect (1986) pp123-147. nayar kMC, Puman Rights: The UN and US

lorelgn ollcy", (1978) 19 Parv lL!, 813, 816-817

44

See PAUST, note 12, at 3-7

45

Idem, at 4

46

Schachter, "International Law in Theory and Practice: General Course in Public International Law", 178

Recueil des cours 21,333-342 (1982-V).

47

E.g., Barcelona Traction Case, ICJ Rep 1970, p.33

14

infers that some provisions can be considered as customary law; in particular, he shows

that some conduct has been universally condemned as violative of the basic concept of

human dignity. The provisions identified by Schachter as customary international law

are the prohibitions of genocide, slavery, torture, mass killings, prolonged arbitrary

imprisonment, systematic racial discriminations and any consistent pattern of gross

violations of internationally-recognized human rights

48

.

Similar cases are enumerated in the Restatement

49

. The status as customary law of

Schachters human rights is maintained and generally accepted; furthermore, the last

point--(g) a consistent pattern of a gross violations of internationally recognized human

rightsmakes this list open to include new rights that eventually become generally

accepted in the future.

The Carter administration

50

and some academic commentators

51

supported an

alternative approach in order to affirm human rights obligations under international law

independently of specific treaty. According to articles 55 and 56 of the UN Charter, All

Members pledge themselves to take joint and separate action in co-operation with the

Organization for the achievement of the

52

. . . universal respect for, and observance of,

human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex,

48

See BRUNO SIMMA AND PHILIP ALSTON, The sources of Human Rights Law: Custom, Jus Cogens, and

General Priniples 12 AusLl. ?.8. lnLL L. 82 (1988-1989)

49

Note 2 at 702

50

Under President Carter, the U.S. Government acknowledged the obligatory character of the Charter's

human rights provisions and appeared to accept the Universal Declaration as an authoritative

interpretation of those provisions, see eg "Address by President Carter to the United Nations General

Assembly" (1977) 76 Dept. of State Bull. 332

51

See Sohn I, "The New International Law: Protection of the Rights of Individuals Rather Than States"

(1982) 32 Amer Univ LR 1, 17; -and Buergenthal T, "International Human Rights Law and Institutions:

Accomplishments and Prospects"(1988) 63 Washington LR 1

52

Art. 56 U.N. Chart

15

language, or religion.

53

In light of this approach, the Universal Declaration and all the

soft law are considered an authoritative interpretation of the obligation contained in the

UN Charter.

I agree with the traditional theory of the customary international law. The need to

protect human rights and the fact that many national constitutions provide the automatic

incorporation of customary international law

54

has caused the distortions of the definition

of international custom in order to recognize human rights as customary international

law, which is accepted by some scholars as though it were religious dogma. From my

perspective, according to the Restatement and Schachter, only a few select human rights

provisions are truly customary law in compliance with the two aforementioned primary

requirements. These select few rights are the prohibitions against genocide, slavery,

murder or causing the disappearance of individuals, torture, prolonged arbitrary

detention and systematic racial discrimination.

The other theories affirm more easily the binding character of human rights

provisions, but their view of international customary law creates total uncertainty: the

rights recognized as international law under such inclusive theories are not written and

potentially are infinite.

The question Are human rights retained as international custom? is thus the

wrong question to ask. The right question is rather What is the most efficient method in

order to defend human rights?. Human rights are not like a car or other material good:

they cannot be exported and cannot be imposed only with rules agreed to by a part of the

global community (for example, Western nations). In my opinion, the most efficient

53

Art. 55 U.N. Chart

54

For example, art 10 Italian Costitution: The Italian legal system conforms to the generally recognized

rules of international law.

16

method to advance respect for human rights is instead improving education, sensitization

and promotion of these rights in academic institutions throughout the world. The world

would thus have new legislators, governments and judges more likely to create and apply

norms respecting international rules of human rights. In sum, the best solution to the

biggest problem of international law, its enforceability, is the creation of a strong culture

of respect of human beings and of positive relations between the States.

SECTION II The Customary Law as United States Law

Is the customary international law part of American law? Most scholars affirm

that it is part of federal common law; however, some academic commentators criticize

this position

55

. In order to understand these two theories, the following sections analyze

some important decisions of U.S. courts.

Before 1938, federal courts applied customary international law in some decisions

in the absence of statutory or constitutional authorization. They considered it sometimes

as an element of natural law; other times, as part of the common law or the law of the

land.

Scholars supporting the modern position maintain that before 1938, customary

international law had the status in the United States of general common law.

56

In a

dissenting opinion, Justice Holmes wrote that the general common law was a

transcendental body of law outside of any particular State but obligatory within it unless

and until changed by the Statute.

57

Thus general common law was similar to the custom

in some civil law legal systems and was not supreme law of the land as were treaties.

55

E.g., Restatment, note 2 at 702

56

CURTIS A. BRADLEY, The Juvenile death penalty and international law, 52 DUKE L.J. 485 (2002) at

552

57

Black & Ehite Taxicab & TRansger CO. V. Brown & Yellow Taxicab & Transfer CO., 276 U.S. 518, 533

(1928) (Holmes, J. dissenting)

17

In 1938, in Erie Railroad v. Tompkins

58

, the Supreme Court held that the general

common law cannot be applied and that the Court should apply only the law of the state,

except in matters governed by the Federal Constitution or by Acts of Congress.

59

What

about the customary international law? An article about the implication of this decision

for international custom in the U.S. legal system was written, one year later, by Jessup

60

.

He cited

61

the Paquete Habana decision (International law is part of our law

62

), an

opinion authored by Justice Marshall ([T]he court is bound by the law of nations, which

is a part of the law of the land

63

), the Kansas v. Colorado decision (Sitting, as it were,

as an international, as well as a domestic tribunal we apply Federal law, state law, and

international law, as the exigencies of the particular case may demand

64

), and the words

of Justice Gray in Hilton v. Guyot:

International law . . . including not only questions of right between nations,

governed by what has been appropriately called the law of nations; but also

questions arising under what is usually called private international law . . . is part

of our law, and must be ascertained and administered by the courts of justice, as

often as such questions are presented in litigation between man and man, duly

submitted to their determination.

65

Finally, he inferred that international law (we can imply international customary law) is

federal common law.

66

This is a fundamental article for the scholars who support the

modern position, and I agree with this analysis.

Jessups article was cited in the Supreme Courts 1964 decision Banco Nacional

58

304 U.S. 64 (1938)

59

Id. at 78

60

hlllp C. !essup, 1he uocLrlne of Lrle 8allroad v. 1ompklns Applled Lo lnLernaLlonal Law, 33 Am. !. lnLl L.

61

Supra at 741

62

(1900) 175 U. S. 677, 700

63

The Nereide (1815), 9 Cr. 388, 423

64

(1907), 206 U. S. 46, 97

65

(1894) 159 U. S. 113, 163

66

See Note 61 at 742

18

de Cuba v. Sabbatino.

67

In that case, the plaintiff, a Cuban national bank, filed a suit

against the expropriation of a ship of sugar made by the Cuban government. The Court

found, applying the same rationale which Jessup applies in his article regarding

international law

68

, that the act of state doctrine was federal common law and thus that

expropriation could not be questioned by U.S. courts. Based on this decision, scholars

who support the modern theory imply that customary international law is federal law,

and its determination in binding on the state courts.

International customary law was applied, I think correctly, in the Filartiga

69

case.

In this case the plaintiff, a Paraguayan immigrant to the U.S., filed a suit in the Eastern

District of New York against another Paraguayan for wrongfully causing the death of

Filartigas 17-year-old son, Felipe. The plaintiff contended that his son was tortured and

killed by Pena, a state official in Paraguay, in retaliation for the plaintiffs political

actions and beliefs. Filartiga brought the action under the Alien Tort Statue, 28 U.S.C.S.

1350, which establishes: The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil

action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty

of the United States. The issue, than, is if it is a violation of the law of the nations,

then of the international law, for an official of a foreign country to torture and kill a

citizen of that nation.

The Court held that courts must interpret international law not as it was in 1789,

67

376 U.S. 398 (1964)

68

Soon thereafter, Professor Philip C. Jessup, now a judge of the International Court of Justice, recognized

the potential dangers were Erie extended to legal problems affecting international relations. He cautioned

that rules of international law should not be left to divergent and perhaps parochial state interpretations.-

Supra at 425

69

Filartiga v. Pena-Irala, 630 F.2d 876

19

but as it has evolved and exists among the nations of the world today.

70

In 1789, there

were few norms recognized as international customary law, primarily concerning

offenses against ambassadors, violations of safe conduct (which were probably

understood to be actionable), and individual actions arising out of prize captures and

piracy (which may well have also been contemplated). However, I think correctly, the

Court decided to apply the contemporaneous international law.

In 1980, the United States was not part of a treaty against the torture, but the

Court of Appeals found that official torture is now prohibited by the law of nations. The

prohibition is clear and unambiguous, and admits of no distinction between treatment of

aliens and citizens.

71

Please note that some scholars think that this decision was

influenced by the publication of the tentative draft of a treaty in 1980

72

. I think that in

this case and in similar cases the application of international customary law in American

courts is established by the Alien Tort Statute.

In 1987 the Restatement (third) was published by the American Law Institute.

The Reporters compared customary international law to treaties: both sources are federal

common law and thus the supreme law of the land

73

. However, a reporters note

specifies that [c]ustomary law does not ordinarily confer legal rights on individuals or

companies.

74

The Restatement thus clearly supports the modern approach.

In Committee of U.S. Citizens Living in Nicaragua v. Reagan the plaintiffs argued

that continuing funding of the Contras, also after the ICJ decision, violated customary

70

Supra, at 881

71

Supra, at 884

72

See Goldsmith, Jack Landman & Curtis Bradley. "Customary International Law as Federal Common

Law: A Critique of the Modern Position," 110 Harvard Law Review 815 (1997), at 835

73

See note 2 111 (d)

74

Note 2 111(4)

20

international law. The Court, then, cited Paquete Habana

75

. In that case, the owner of

fishing vessels captured and condemned as a war prize sought compensation from the

U.S. on the grounds of customary law. The Court applied international law, but specified

that: where there is no treaty, and no controlling executive or legislative act or judicial

decision, resort must be had to the customs and usages of nations.

76

Then the Court

denied the claim because a norm of customary international law cannot supersede or

modify a statute approved by the Congress.

In 2004 the Supreme Court decided an important case regarding the application of

the customary international law and the Alien Torts Act. In Soza v. Alvarez-Machain

77

the petitioner abducted Alvarez, who was in Mexico, and delivered him to federal agents

in the United States where he was arrested because the U.S. District Court for the Central

District of California had issued a warrant for his arrest. Returned in Mexico, after he was

acquitted, Alvarez began a civil action against Soza. What matters here is that Alvarez

sought damages from the United States under the FTCA, alleging false arrest, and from

Sosa under the ATS, for a violation of the law of nations.

Regarding the issue related to the Alien Tort Act, the Court enumerated and

explained all the precedent decisions, starting with Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins. It found that

there are limited enclaves in which federal courts may derive some substantive law in a

common law way.

78

The Alien Tort Statue, then, is one of these enclaves, for which

the Court should apply the law of nations. Following the path of Filartiga (even if on this

point Justice Scalia dissents), the Court applied contemporaneous international law and

75

175 U.S. 677 (Sup. Court, 1900)

76

Supra at 702

77

542 U.S. 692 (Sup. Court, 2004)

78

Supra at 729

21

held that the modern federal court may recognize more violations under modern

customary international law than those which existed when the ATS was enacted

79

.

Further, the Court found that the prohibition against arbitrary arrest was a defined rule of

international customary law. However, in this case the Supreme Court held that the

Alvarez detention, less than a day long (after he was delivered to U.S. agents), did not

violate a norm of international law. The Court, then, reversed the judgment of the Court

of Appeals.

What are the other consequences of the modern theory? Concerning the legal

status of international customary law in relation to statutes and treaties, the modern

scholars argue the last in time rule prevails. But the Restatement

80

objects that the

international customary law arising from acts of the President (and the sole act of the

President) cannot prevail over a law of United States Congress.

As federal common law, then Supreme Law of the land the norms of

international customary law preempt state law. The modern scholars affirm that the

Constitution, granting foreign relations power to the federal government, provides its

international law norms with preemptive character.

The traditional scholars affirm that Customary Law is not federal common

law. In particular, they argue that considering international customary law as federal

common law is a threat for the principle of separation of powers because the political

branches would be bound by the judicial interpretation of it.

Further, they affirm that the Constitution does not explicitly provide international

customary law with preemptive power over state law; in contrast to the Commerce

79

See supra at 749

80

See note 2 115

22

Clause, which states that the United States Congress has the power to regulate commerce

with foreign nations, among the states, and with the Native American tribes

81

.

The academic commentators who support the traditional view affirm that

customary international law is not the law of the United States, is not part of the federal

common law, and, like Justice Scalia, argue that the Alien Tort Statute does not permit

the recognition of contemporaneous international norms.

In other words, we can define the traditional theory as a strictly dualistic:

according to the traditional scholars only the law approved by Congress and treaties

which are clearing self-executing (by reason of a clear statement) are the law of the

land to be applied by the judiciary. In contrast, the modern theory supports a monistic

system: all the customary international law is federal law and can be applied by the judge.

In my opinion, in light of the decisions enumerated in this paper, customary law is the

federal law of U.S. However, I do share some of the concerns of the traditional school

with regard to the uncertainty of the law: custom is not written, and this gives the judges

a law-making power. But I do not think that the best solution is concluding that the

customary international law cannot be applied at all; rather, I agree with Justice Souter

who in Sosa wrote, [J]udicial power would be exercised on the understanding that the

door is still ajar subject to vigilant door-keeping.

82

Section III- The Jus Cogens

According to the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties

83

, a jus cogens norm

is a norm accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole

as a norm from which no derogation is permitted and which can be modified only by a

81

U.S. Const. Ar. I 8 cl. 3

82

Note 77 at 729

83

Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties, art.53, May, 23, 1969, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331

23

subsequent norm of general international law having the same character. Unlike the

customary international law, the definition of a preemptive norm lacks the general

practice of the state. Originally it was considered only as a limitation on international

freedom of contract: thirty-two years before the signing of the Vienna Convention,

Verdross wrote that a State can be bound by a Treaty which makes it no longer able to

protect at all () the life, the liberty, the honor, the property of men on its territory,

84

or

some fundamental human rights.

Later some commentators argued that jus cogens was not only a rule concerning

the validity of the treaties but also a limitation on non-treaty conduct. There are many

opinions about the sources and the content of preemptory norms. This section

85

analyzes

various opinions and concludes that jus cogens exist and can be applied not only in the

law of the treaty.

The theories which reject the notion of jus cogens, even if supported by different

justifications, have in common a voluntarist view of international law according to which

a State cannot be bound by rules freely accepted as legally binding.

Among the theories which affirm the existence of jus cogens, some scholars

consider it as international public order

86

, rules which state the fundamental values of the

international community. Other academic commentators believe preemptory norms arise

from the natural law: jus cogens is a law needed by all (jus necessarium pro omnium)

87

.

84

von verdross, lorbldden 1raLles ln lnLernaLlonal Law", 31 AJIL (1937) 571, at 574

85

For a general discussion about these theries, see Robert KOLB, Theorie du Ius Cogens International,

2003 REV. BELGE DE DROIT INTERNATIONAL 5, 14-28

86

See, e.g., A. GOMEZ 8C8LLuC, Le lus cogens lnLernaLlonal: sa geneese, sa naLure, ses foncLlons" ,

RCADI, vol. 172, 1981-lll, pp. 170 eL a., C.A. CP8l1LnCn, !us cogens:Cuardlng lnLeresLs lundamenLal

Lo lnLernaLlonal ocleLy", 28, Vir. J. Intl L. , 643

87

See, e.g., F.A. VON DER HEYDTE, ASDI, vol. 25, 1968, pag. 18 I. DETTER, The International Legal Order,

Aldershot, 1994

24

According to Verdross

88

, jus cogens is part of the general principles of law recognized

by civilized nations established by the Statue of the International Court of Justice. As

law recognized by civilized nations they do not represent an erosion of sovereignty

but are limits universally recognized and accepted in order to preserve the dignity and the

well-being of humanity.

I agree with Simma and Alston

89

who conclude that the obligation to respect

fundamental human rights is an obligation under general international law, but these

human rights are not all those established by the Declaration but those specified by

binding treaties and few others protected by preemptive norms.

The most important problem is determining the contents of jus cogens. On their

limits depend the seriousness, the recognition, and the application of the preemptory

norms. Criticizing the uncertainty of the jus cogens, Andrea Bianchi

90

compares the

preemptive norms to some mythological figures. In an ironic article published in 1990,

Anthony DAmato

91

wrote that jus cogens is an asset, enabling any writer to christen

any ordinary norm of his or her choice as a new

92

preemptive norm. He concluded his

article by affirming that the theory of jus cogens must answer the following questions:

What is the utility of a norm of jus cogens?

How does a purported norm of jus cogens arise?

Once one arises, how can international law change it or get rid of it?

93

In my opinion the jus cogens norms have the purpose of establishing some rules which

88

See note 83

89

See Note 47 at 105

90

Andrea Bianchi, Human Rights and the Magic of Jus Cogens, 19 EJIL 491 (2008)

91

AnLhony uamaLo, Its a ird, its a plane, its jus ogens! , 6 Conn. !. lnLl L. 1 (1990-1991)

92

Supra at 1

93

Supra at 6

25

cannot be derogated, even in an emergency. After centuries of wars and violence, after

the Second World War, the genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda and Bosnia, we have

learned that there are some rights which must be unassailable. The historical events of

the last fifty years have taught us that the traditional sources of international law are not

sufficient to prevent major slaughters: Srebrenia, in the center of the Europe, was the

theater of the biggest European genocide after the Second World War, with 8,373 men,

women and children killed by the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) under the command

of General Ratko Mladi during the Bosnian war.

A norm of jus cogens arises from different kinds of evidence like numerous

resolutions of the U.N. and other international organizations condemning violations of a

specific rights as gross breaches of international law and statements by numerous national

officials criticizing other States for serious violations of specific rights. Normally, the

formation of a jus cogens norm-contrary to customrequires a long period in which

numerous official declarations which strongly condemn violation of a precise right are

issued. A shocking world event implying the gross violation of one or more specific

rights could shorten this laps of time. For example, during the Middle Age the destruction

of an ethnic or racial group (what we call genocide) was considered lawful in order to

preserve religious values. The Armenian Genocide during the First World War, and the

Holocaust during the Second, let us understand in few years that similar acts are threats to

humanity.

During this time the norm is implicitly or explicitly recognized by the States as

fundamental for human existence.

After the Second World War numerous official acts condemned the genocide,

26

including a Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,

adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in December 1948 as General

Assembly Resolution 260.

Due to their nature, the preemptive norms cannot be changed or abrogated. For

example the prohibition against torture cannot be derogated because:

The result of torture depends on a mans predisposition and on calculation, which

vary from man to man according to their hardihood and sensibility, so that, with

this method, a mathematician would settle problems better than a judge. Given the

strength of an innocent mans muscles and the sensitivity of his sinews, one need

only find the right level of pain to make him admit his guilt of a given crime

94

.

As early as 1748 Cesare Beccaria, an Italian lawyer, in his book Dei Delitti e delle pene

(On Crimes and Punishments) wrote these words against torture. In September 2009

Shane OMara, Professor of Neuroscience at Trinity College Institute of Dublin,

convincingly demonstrated that a tortured man is most likely to lie

95

. These motives are

enough to affirm that torturing is imposing useless suffering

96

.

Lasting, regarding the prohibition of slavery, in 1926 it was officially condemned

with a Convention concerning the slavery. Article 4 of Universal Declaration of Human

Rights prohibits slavery and the slave trade in all their forms and a lot of binding

conventions or declarations condemned slavery

97

.

94

Cesare Beccaria, On Crimes and On Punishments and other writings, Cambridge University Press, p. 42.

95

See Shane OMara, Torturing the Brain: On the folk psychology and folk neurobiology motivating

enhanced and coercive interrogation techniques,

http://blogs.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/Torturing%20the%20Brain%20TiCS%202009%20SOM%20no

n-proof%20version.pdf

96

In my thesis I will write a chapter about the use of torture in the War against the Terror

97

For example: Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions

and Practices Similar to Slavery of 30 April 1956. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination against Women of 18 December 1979, Art. 6 ,34 ,35 Declaration from General Assembly

on the Elimination of Violence against Women of 20 December 1993. Optional Protocol to the Convention

on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography of 25 May 2000.

(Committee on the Rights of the Child ). Convention against Transnational Organized Crime of 15

27

In sum, in my opinion jus cogens norms arise with the repetition of official

condemnation of an act, but their importance for the survival of human beings make them

unchangeable and not-abrogable.

Then, I think that the content of jus cogens are the norms which prohibit

genocide, slavery and torture.

What are the implications of my theory? When and how can jus cogens be

applied? First of all, an international agreement that violates a preemptive norm is void

98

,

according to the Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaty. Further, the administrative

judges can declare void an act of a State that violates a jus cogens norm. For example, if

the government of a nation orders a genocide, the administrative judges of that nation can

declare that act avoid.

Concerning international responsibility, surely the violation of a preemptory norm

implies it; however, the International Court of Justice in the case concerning Armed

Activities in the Territory of the Congo between the Democratic Republic of Congo and

Rwanda held that a jus cogens norm may not provide a basis for the jurisdiction of the

Court if an explicit reservation to a treaty excludes the submission of a particular kind of

dispute to the ICJ. Yet I respectfully disagree with this decision. In my view, in order to

grant effectively the respect of a preemptive norm, a jus cogens norm always implies the

inherent jurisdiction of a Court: national, if one party of the judgment has no international

personality (it is not a State or an International Organization), an international court (like

December 2000. Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the

United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. (New York, 15 November 2000)

Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children,

supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. (New York, 15

November 2000)

98

Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties, art.53, 54 and 66, May, 23, 1969, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331

28

the International Court of Justice) if all of the parties have the international personality.

Yet even if I do not agree with it, the decision represents an evolution of the notion of jus

cogens and of its use by the International Court of Justice: this is the first occasion on

which the ICJ has given its support to the notion of jus cogens Judge ad hoc Dugard,

nominated by Rwanda, wrote in his separate opinion. In 1996 in the Advisory Opinion on

the legal use or threat of use of Nuclear Weapons, the Court used the term

intransgressible principles of humanitarian law.

99

In other decisions the ICJ used the

notion of erga omnes obligation instead of jus cogens norm. But in the Armed Activity

decision, the Court recognized the existence of jus cogens norms comparing them to the

obligations erga omnes regarding the relationship between preemptory norms and the

establishment of the Courts jurisdiction: both do not trump the consent requirement to

establish the jurisdiction of the Court.

Analyzing this evolution I could consider myself as long-sighted: my theories

would not be applied now by the ICJ, but possibly, I hope, they will applied in coming

years.

A jus cogens rule cannot be a legal basis for a penal sanction. According to the

principle Nulla paena, nullum crimen sine lege poenali scripta, a preemptive norm

cannot be used by a court in order to impose a punishment: the jus cogens norms are not

written, then the judge would arbitrarily decide the punishment.

A State which violates a jus cogens is instead civilly responsible for

compensatory damages towards the victims, and the preemptive nature of the rule trumps

the jurisdictional immunity as a sovereign state. In the case Ferrini v. Federal Republic of

99

Armed Activities in the Territor of the Congo, (New Application:2002) (Democratic Republic of Congo

v. Rwanda), Jurisdiction and Ammissibility [2006] ICJ Rep 1, at paras 64 and 125

29

Germany

100

, the plaintiff was imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp and sued

Germany for reparations. The Italian Supreme Court affirmed the existence of the Italian

courts jurisdiction. First, it recognized the German acts in Italy during the Second World

War as international crimes. Then the Court affirmed that the protection of human rights

is provided by norms which cannot be derogated and prevail over all other conventional

and customary norms, including those which relate to State immunity.

101

Note that here

the Court described preemptive norms, but it did not call them jus cogens. In order to

support his opinion, the Italian judges cited art. 146 of the 1949 Geneva Convention IV

relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, which establishes that

States are obliged to suppress the breach of fundamental human rights. They further cited

article 155 of the same Convention, which obliges the State not to recognize the

legitimacy of those circumstances which gave rise to its commission.

102

Finally, the

Court noted that, unlike similar cases decided by foreign courts

103

, in this case the

criminal acts were committed in the country in which the legal action was brought. This

decision was proper because it has the purpose of protecting effectively jus cogens

norms--the prohibitions against torture and arbitrary arrest.

The Jus Cogens in the U.S. Court

The Courts of the United States are most likely to recognize the jus cogens as

international law sources, but the violation of a preemptive norm is not considered as an

exception to the immunity from the jurisdiction of U.S.

In Committee of U.S. Citizens living in Nicaragua v. Reagan, the plaintiff alleged

100

Cass., sez. Un., 11 March 2004, n. 5044, RDI 2004, p.540 ; 128 International Law Report, 659

101

128 International Law Report, 668

102

Supra

103

See, e.g., Al-Adsani, e Houshang Bouzari, 61; Superior Court of Justice Ontario (Canada), 1 maggio

2002

30

that the continuing funding to the Contras was a violation of a preemptive norm

establishing that the parties who have submitted to an international court shall abide by

its judgment. In order to verify this affirmation, the Court applied the same criteria of

customary international law: state practice and opinion juris. Finally, the judges held that

the purported preemptive norm is not a jus cogens rule, but such basic norms of

international law as the prohibition against murder or slavery () may well restrain

our government in the same way that the Constitution restrains it. I agree with the

decision of the Court even if I respectfully dissent from the part in which it applies the

elements of customary international law in order to verify the existence of the jus cogens

norm.

Instead in Alvarez-Machain v. United States

104

, judgment of appeal of the Soza v.

Alvarez Machain case, the Court of Appeals of the ninth Circuit held that whereas

customary international law derives solely from the consent of states, the fundamental

and universal norms constituting jus cogens transcend such consent

105

. I fully agree with

this conclusion.

Contrary to the Italian Supreme Court, the U.S. judges do not retain that the

violations of jus cogens norms are exceptions to the rule of immunity of foreign

sovereigns established by Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976.

106

The case

Sampson v. Federal Republic of Germany is similar to the Ferrini case. The plaintiff was

imprisoned by the Nazis during the Second World War and filed a suit against Germany

claiming reparations. The Court held that even if Germany violated jus cogens norms, the

Court lacked jurisdiction because Congress did not create an exception to foreign

104

331 F.3d 604

105

Supra at 613

106

28 U.S.C.S. 1330, 1602-1611,

31

sovereign immunity under the Foreign Severeign Immunities Act.

107

In my view, according to the Italian Corte di Cassazione, the violation of jus

cogens norms trumps the immunity of a State in order to grant an effective protection of

fundamental rights. This is not an erosion of sovereignty, it is only the logical

implication of the existence of preemptive norms, which grant a select few fundamental

human rights.

Conclusion: In faithfulness bringing forth justice

108

To every action there is always an equal and opposite reaction

Newtons Third Law

Analyzing my paper, a reader can understand that I do not consider International

Law as a simple instrument to rule foreign relations, but an important body of norms

which should grant the pacific coexistence of States. However I do not theorize the end of

the sovereignty of States in favor of rules decided by International Organizations or the

imposition on all the Nations of numerous rules not accepted by them. My theory goes

beyond the principle established by the Westphalia peace, cuius regio eius religio, the

view in which the law of a State is like an iron sphere which cannot be pervaded by

external rules.

I think that there are some norms valid for all men and all States, independently of

race, religion or culture. The consequence for violations of these norms is not only a

religious sin or a moral condemnation; instead is a necessary response to an injection of

hatred that poses risks for the existence of human beings.

107

250 F.3d 1145, (7

th

Cir., 2001)

108

Isaiah, 42,3

32

In my opinion Newtons third law is not valid only for dynamic, but also for the

human behavior. What is the reaction of a people that is victim of a genocide? Or of

massive torture? Is it not true that violence creates violence? For these reasons the rules

that I retain as jus cogens norms cannot be derogated even in case of emergency. The

violations of this rights create hatred. The hatred gives birth to the violence. The violence

is a threat for the national security of a country and for all people.

The notion of a preemptive norm is the legal concept which brings these rules

into force in International Law without the risk that they be modified or rejected by a

nation. In fact two of the others primary sources of international law, treaties and

International Customary Law, can be easily modified or derogated.

Regarding the relationship between International Law and domestic laws (in

particular, the U.S. legal system), I am in favor of a flexible dualistic system: the Treaties

come in force because they are ratified and the International Customary Law because

there is a domestic law (ordinary or constitutional) which authorizes its application; no

ratification or authorization is requested in order to apply the jus cogens norms which can

be interpreted also in light of the treaties.

Further, in order to grant the effective protection of human rights, it is important

that the Treaties which establish them should not be abrogated or modified by a normal

legislative act: in fact they should bind not only the executive power but also the

legislative.

In conclusion, the principal purpose of International Law, in order to defend all

people and all human beings, is avoiding this injection of hate: in faithfulness bringing

forth justice. That is settling common rules among the nations mainly through the

33

agreement of States but also through those few norms essential for the pacific coexistence

of peoples.

The purpose of International Law is also to keep ones head when all about

are losing theirs

109

, not permitting that the fear of the others should justify the violations

of fundamental rights, because they that sow the wind, they shall reap the whirlwind

110

.

109

Ryuard Kipling, If

110

Hosea 8,7

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

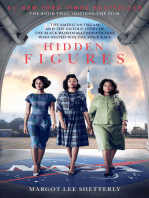

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Punjab Panchayat Samitis and Zila Parishads Services RulesDocument27 pagesThe Punjab Panchayat Samitis and Zila Parishads Services RulesHarjot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (Trips)Document34 pagesTrade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (Trips)Harjot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Payment of Wages Act 1936Document22 pagesPayment of Wages Act 1936Sunita ChowdhuryPas encore d'évaluation

- RTI Paper - 2005 Ombuds ConfDocument9 pagesRTI Paper - 2005 Ombuds ConfHarjot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Death and Its Medico-Legal AspectsDocument12 pagesDeath and Its Medico-Legal AspectsHarjot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Gift DeedDocument9 pagesGift DeedHarjot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- M.A. Economics 201 15Document57 pagesM.A. Economics 201 15Harjot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- NepalDocument8 pagesNepalHarjot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- B.A. LLB - HonsDocument253 pagesB.A. LLB - HonsAnurag SindhalPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument18 pagesChild Labour in IndiaAaditya BhattPas encore d'évaluation

- Public International Law & Human RightsDocument37 pagesPublic International Law & Human RightsVenkata Ramana100% (3)

- International Islamic University Islamabad: " The Snowball - Warren Buffett and The Business of Life "Document10 pagesInternational Islamic University Islamabad: " The Snowball - Warren Buffett and The Business of Life "ArslanPas encore d'évaluation

- International Islamic University Islamabad: " The Snowball - Warren Buffett and The Business of Life "Document10 pagesInternational Islamic University Islamabad: " The Snowball - Warren Buffett and The Business of Life "ArslanPas encore d'évaluation

- Documents StackDocument1 pageDocuments StackDan MPas encore d'évaluation

- PSM Diet ChartDocument5 pagesPSM Diet ChartHarjot SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Soni Environmental Law ProjectDocument20 pagesSoni Environmental Law ProjectShashank PathakPas encore d'évaluation

- LL.B (THREE YEAR COURSE) Part-I (Sem I&II)Document17 pagesLL.B (THREE YEAR COURSE) Part-I (Sem I&II)Abhi JainPas encore d'évaluation

- I 212instrDocument18 pagesI 212instrAgustin BisonoPas encore d'évaluation

- DFA-Batch 61 - OCAV4539 LBI DOT - DOT - 21FN - 20210901Document2 pagesDFA-Batch 61 - OCAV4539 LBI DOT - DOT - 21FN - 20210901AinsleePas encore d'évaluation

- Sources of International LawDocument26 pagesSources of International LawRaju KD100% (1)

- Co Kim Cham vs. ValdezDocument16 pagesCo Kim Cham vs. ValdezJames OcampoPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 Chinese JIntl L247Document35 pages11 Chinese JIntl L247Naing Tint LayPas encore d'évaluation

- Imm5812 2-ZZ2TCQTDocument2 pagesImm5812 2-ZZ2TCQTDanil MoskvitinPas encore d'évaluation

- Henley Passport Index 2024Document3 pagesHenley Passport Index 2024Index.hrPas encore d'évaluation

- ACQUISITION OF TERRITORY BY A STATE, Dr. Godber T.Document5 pagesACQUISITION OF TERRITORY BY A STATE, Dr. Godber T.Aijuka Allan Clarkson RichardPas encore d'évaluation

- AsylumDocument6 pagesAsylumjkscalPas encore d'évaluation

- Institutional Treatment of OffendersDocument3 pagesInstitutional Treatment of OffendersKapil GujjarPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 12. CitizenshipDocument27 pagesChapter 12. CitizenshipOnin MatreoPas encore d'évaluation

- Birthright Citizenship Around The WorldDocument48 pagesBirthright Citizenship Around The WorldSlobodan PesicPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 173034 Pharmaceutical Vs DuqueDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 173034 Pharmaceutical Vs DuqueApoi Faminiano100% (4)

- WHO Vs AquinoDocument2 pagesWHO Vs AquinoRion MargatePas encore d'évaluation

- Baldacinni - EU Immigration and Asylum Law and PolicyDocument582 pagesBaldacinni - EU Immigration and Asylum Law and PolicySara Kekus100% (1)

- Ichong Vs Hernandez DigestDocument6 pagesIchong Vs Hernandez DigestFennyNuñalaPas encore d'évaluation

- International Criminal LawDocument17 pagesInternational Criminal Lawkimendero100% (2)

- Imm5988 2-VF0NBL6Document1 pageImm5988 2-VF0NBL6Sonia de la TorrePas encore d'évaluation

- The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), 8 U.S.C. 1101 Et Seq.Document49 pagesThe Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), 8 U.S.C. 1101 Et Seq.Beverly TranPas encore d'évaluation

- CP Netherlands ENGDocument8 pagesCP Netherlands ENGFlower PowerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Republic of LOMAR Sovereignty and International LawDocument13 pagesThe Republic of LOMAR Sovereignty and International LawRoyalHouseofRA UruguayPas encore d'évaluation

- Tourist Visa Checklist - New Delhi2Document1 pageTourist Visa Checklist - New Delhi2Shahbaz HasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict of Laws Course SyllabusDocument3 pagesConflict of Laws Course SyllabusDanny LabordoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2023 Bench Memo v. 1.0 1Document30 pages2023 Bench Memo v. 1.0 1NUWAGABA Kansime philbertPas encore d'évaluation

- Naturalization Stub IndexDocument271 pagesNaturalization Stub IndexDinner and a Donkey Show TheatrePas encore d'évaluation

- 2008 L.E.I. Notes in Public International LawDocument89 pages2008 L.E.I. Notes in Public International LawDanniel James Ancheta78% (9)

- AnglDocument1 pageAnglDarja OvcarukaPas encore d'évaluation

- Memorial For The Tehankee Center For The Law Moot Court CompetitionDocument52 pagesMemorial For The Tehankee Center For The Law Moot Court CompetitionTim PuertosPas encore d'évaluation