Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Notes Material

Transféré par

Stuti Baradia0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

55 vues19 pageshma

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documenthma

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

55 vues19 pagesNotes Material

Transféré par

Stuti Baradiahma

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 19

Hindu Law (part 1)

Application of Hindu Law

Persons subject to Hindu Law-

Shastri Yagna Purushdasji v. Muldas Bhundardas Vaishya- It is extremely difficult, though

not impossible, to define the Hindu religion in the way the other religions are defined. It

embraces numerous views and ways of life.

The term Hindu is not to be found anywhere in the Dharmashastras. It is a foreign word. It is

derived from the word Sindhu. Sindhu is the name of a river in Indian sub-continent. The word

Sindhu was mis-spelled as Hindu by the Persians. The sub-continent came to be known as

Hindustan and its people as Hindus. Thus etymologically, the word Hindu does not signify a

religion; it refers to a territory or nation.

Hindu law is a personal law. So, Hindu law should define who is a Hindu, and upon whom the

Hindu law applies.

A portion of Hindu law has been codified by Parliament in four Acts-

i) The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

ii) The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1955

iii) The Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1955

iv) The Succession Act, 1956

According to these Acts, a Hindu is a person who-

Is a Hindu by religion in any of its form or development

Is a Buddhist, Jain or Sikh by religion

Any person who domiciled in India, who is not a Muslim, Christian, Persi or Jew by

religion

Hindus domiciled in the territories to which the Act extends

Followers of Hindu law

Followers of Hindu Law-

i) Legitimate child of Hindu parents

ii) Illegitimate child of Hindu parents

iii) Children of one Hindu parent

iv) Converted- The law was that the conversion was not accepted. But later it was accepted but

the converted person was given the lowest caste. All Hindu laws will be applicable upon him

except the succession.

Requirement of conversion- (i) Unequivocal conduct, (ii) Bona fide intention, (iii) No ceremony

is required and (iv) His motive is not important (Raman Nadar v. Snehapoo).

Persons not subject to Hindu Law-

i) Non-Hindu child of one Hindu parent

ii) Converts from Hindu religion

Abraham v. Abraham- Those who convert to Islam and other castesare not subject to Hindu

Law.

Doctrine of factum valet-

It is a doctrine of Hindu law, which was originally enunciated by the author of the Dayabhaga,

and also recognized by the followers of the Mitakshara, that a fact cannot be altered by a

hundred texts. The text referred to are directory texts, as opposed to mandatory texts. The

maxim, therefore, means that if a fact is accomplished, i.e., if an act is done and finally

completed, although it may contravene a hundred directory texts, the fact will nevertheless stand,

and the act done will be deemed to be legal and binding.

This doctrine came from Roman maxim factum valet quod fieri non debuit which literally

means that what ought not to be done become valid when done.

Sources of Hindu Law

Founder of Mitakshara School Vijaneshwar said, sources are the means of knowing law.

Hindu law is based on tradition and analytical in nature. Law is part of Dharma. So the sources

of Dharma are the sources of Hindu law. But in a secular point of view- it is a man-made

institution of control.

Sources may be arranged in the following order-

i) Legislation

ii) Dharma Shastras

The Vedas

The Smritis

The Puranas

iii) Sadachar (Custom)

iv) Commentaries and Digests

v) Precedents

vi) Principles of justice, equity and good conscience.

These laws are applicable as long as they are consistent to the Constitution.

Krishna Sing v. Mathura Ahir- The ban which was upon the Sudras is abrogated, because it is

inconsistent with the Fundamental Rights of the Constitution.

i) Legislation-

Main legislations are-

The Caste Disabilities Removal Act, 1850

The Hindu Widow Remarriage Act, 1856

The Majority Act, 1875

Transfer of Property Act, 1882 (overrides the Hindu Law of Property).

The Disposition of Property Act, 1960

The Succession Act, 1956

The Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929

The Special Marriage Act, 1954

ii) Dharmashastra-

The term Shastra came from shas which means to teach. Dharmashastra means teacher of

dharma. It has two meanings-

a) Comprehensive- it includes Vedas, Smritis and Puranas

b) Limited- It includes only Smritis.

Dharma is divided into six-

i) Barna Dharma It is Dharma of the castes. It provides the laws applicable to different

castes.

ii) Ashrama Dharma It means four stages of life: (a) Brahmacharya (b) Grihastha (c)

Banaprashta (d) Sanyas.

iii) Barnashrama Dharma It is the combination of the first two Dharmas.

iv) Guna Dharma It means inherent nature of a thing.

v) Nimitto Dharma It is the secondary Dharma in absence of primary Dharma.

vi) Sadharana Dharma which is proper Dharma for a person in ordinary situation.

Vedas- Synonym to Vedas is Shruti. Shru means to hear. Hindus believe that the Vedas

are heard from God and written. There are four Vedas- (a) Rig Veda (b) Yajur Veda (c)

Sham Veda (d) Atharva Veda.

Each Veda has three parts-

i) Sanhita

ii) Brahmin It describes what the duties are

iii) Upanishad It describes the consequence to perform a duty.

Smriti- Derived from Smri which means to remember. People remembered from the

words of the sages, it is not from the God directly.

Smriti is divided into 2 parts-

i) Dharma sutra- it is mainly prose

ii) Dharma Shastra- it is mainly poetry (sloka).

Exact number of Smritis is unknown. Some authentic Smritis are-

Manu, Vaisistha, Brihaspati, Yagnavalkya, Vyas, Kotilya, Parashar, Katyana.

There are 3 rules in every Smriti-

i) Achar Morality

ii) Vyavahar Rules that the king or judge used to apply insettling disputes in the

administration of justice.

iii) Prayaschit Penal provisions for commission of a wrong. There are both substantive and

procedural laws. I t has 2 elements- (a) An inner intention to reform oneself, (b) A readiness

for punishment for committing an offence.

I f there is conflict between 2 Smritis, there is difference in opinion. According to Brihaspati,

Manu is above all Smritis. According to some, one has to choose among to conflicting

Smritis. According to others, the more logical one will be accepted.

Purana- It is a book containing five matters-

i) Creation

ii) End of creation

iii) Dynasty

iv) Manavantar

v) History of ancient dynasties

There are 18 Puranas, 18 Upa-puranas and 18 Upapa Puranas.

If there is conflict between Purana and Smriti, Smriti shall prevail.

iii) Sadachar (Custom)-

Custom is one of the most important sources of Hindu Law. Where there is a conflict between a

custom and the text of the Smritis, such custom will override the text.

Collector of Madura v. Mootoo Ramalinga (Ramnads case) Clear proof of usage will

outweigh the written text of law.

Customs are divided into-

(a) Local customs- are confined to a particular locality like a district, town or village.

(b) Class customs are the customs of a caste or a sect of the community or the followers of a

particular profession or occupation.

(c) Family customs are confined to a particular family only, and do not apply to those who are

not members of such family.

Essentials of valid custom-

i) Ancientness A custom must be minimum 100 years old.

ii) Certainty - Universality in observance is absolutely necessary.

iii) Reasonableness It should be in accordance with rules of justice, equity and good

conscience.

iv) Continuity It must be continuous without interruption.

v) Public policy It must not be against public policy.

vi) Uniformity It must be uniformly performed.

If a custom meets the abovementioned requirements, it becomes binding.

iv) Commentary and Digests-

Commentary is the interpretation of the Smritis by the scholars. It also includes the customs and

usages which the commentators found prevailing around them. Despite the fact such

commentators have modified the original texts in order to bring them in line with the local

customs and conditions, the commentaries are now considered to be more authoritative than the

original texts themselves.

Collector of Madura v. Moottoo Ramalinga- Clear proof of usage will outweigh the written

text of the law.

These commentaries gave rise to different schools known as the Mitakshara and Dayabhaga.

Collection of commentaries is called Digests.

Features of commentary and digest-

i) They have tried to make the subject simple and easy to understand.

ii) We find quotations of several works (texts)

iii) Topics of Dharma have been widely classified by the digest

iv) They have included custom and usages prevailing during their time

v) Commentary and digests kept law abreast of life.

A lot of commentaries have been made on Manusmriti. These are called Manu Tika.

Commentaries were started to be written down from 4-5 century and digests were from 12

century.

Authority of commentary and digest-

Atmaram v. Bajirao If Commentary and digest conflict with Smriti or Purana, Commentary

and digest shall prevail.

v) Precedent

vi) Principles of J ustice, Equity and Good conscience

Schools of Hindu Law

School means rules and principles of Hindu Law which are divided into opinion. It is not

codified. There are two Schools of Hindu Law- (a) Mitakshara (b) Dayabhaga.

Mitakshara School prevails throughout India except in Bengal. It is a running commentary on the

code of Yagnavalkya. Mitakshara is an orthodox School whereas the Dayabhaga is Reformist

School.

The Mitakshara and Dayabhaga Schools differed on important issues as regards the rules of

inheritance. However, this branch of the law is now codified by the Hindu Succession Act, 1956,

which has dissolved the differences between the two. Today, the main difference between them

is on joint family system.

Mitakshara- Rights in the joint family property is acquired by birth, and as a rule, females have

no right of succession to the family property. The right to property passes by survivorship to the

other male members of the family.

Dayabhaga- Rights in the joint family property are acquired by inheritance or by will, and the

share of a deceased male member goes to his widow in default of a closed heir.

Differences between the two Schools in Coparcenary-

Mitakshara Dayabhaga

i) Right of a son by birth in the ancestral

property equal to the interest of his father.

i) A son is entitled to his ancestral property

only on the death of his father. The father is

the absolute owner of his property in his

lifetime.

ii) A son becomes coparcener right after his

birth. His right is applicable to the property

of his grandfather and grand-grandfather.

ii) A son becomes coparcener by death of his

father. This right is not available within the

property of his father, grandfather or grand-

grandfather.

iii) Everyone is entitled to the property as a

unit. Their shares are not defined. They have

only the commodity of ownership. There is

joint-tenancy.

iii) Everyones share is defined. There is

tenancy-in-common.

iv) One cannot transfer his share to the third

party.

iv) One can transfer his share.

v) The joint-property can be partitioned. In

that case, it will be partitioned as it was in

case of the father.

v) As the shares are defined, one can easily

partition with his share.

Differences between the two Schools in Succession-

Mitakshara- Property of a deceased Hindu is partitioned into two ways as the property is of two

types- (a) Ancestors property, (b) Separate property.

Ancestors property is partitioned in accordance to the Rules of Survivorship. But a Separate

property is partitioned to the descendants.

Dayabhaga- Property is of two types- (a) Joint, (b) Separate. The descendants inherits the

property whatever type it is.

Mitakshara- In default of close heir, brother and immediate survivors inherit, the wife does not

inherit.

Dayabhaga- If coparcener dies, his widow will get the property in default of a close heir but she

cannot alienate.

Mitakshara- The order of heirs is decided by mereness of blood.

Dayabhaga- The order of heirs is decided by the competence to offer Pinda and Sraddho to the

deceased.

Effect of migration

A person follows the school of his area. But if he migrates to another place, he will follow the

School of that locality. This has been decided in various cases-

Gope v. Manjura Govalin- The burden of proving migration lies on him who pleads it. The

original place of a family can be inferred from the chief characteristics of that family.

Keshavarao v. Swadeshrao, 1938- Migration means leaving to another place forever. But if a

place is divided into two administrative area, that will not be regarded as migration.

Moolchand v. Mrs. Amrita Bai- A person migrates will all of his personal laws. Personal law

unlike local law moves with whom he covers.

Notraz v. Subba Raya- A person can be given an option to give up the law of the old place and

adopt the new one.

Hindu Marriage

Hindu marriage is a religious sacrament. Unlike Islami law, it is not contract. Hindu philosophers

treated Hindu marriage as a part of Achar (custom) but not a part of law (vyavahar). It is an act

by performance of which a thing becomes fit for a certain purpose. These purposes are-

i) Performance of sacrifice

ii) Pleasure and procreation of children (Children save their fathers from hell-fire)

Marriage is compulsory for all Hindus except for lifetime students.

Forms of marriage-

There are 8 forms of marriage, 4 of them are approved and 4 of them are not approved.

Approved forms are-

Brahma, Daiva, Arsha, Prajapatya.

Unapproved forms are-

Gandharva, Asura, Rakshas, Paishacha

Only 2 forms are available now- Brahma and Asura. Brahma form is approved by law.

I n Brahma form- Bride is a gift to the bridegroom and there is no consideration.

I n Asura form- The husband is giving an amount to father of the bride. It is called Shulka. It is

called sale of the daughter by money.

Caste and marriage-

To marry in the same caste was not approved; because a Hindu believed that people of the same

caste are Agnate (Agnate means where there is no female intervention, i.e. Uncle etc.) Marrying

daughter of Agnate was not allowed. Females of same caste were considered to be the daughters

of Agnates.

Unapproved marriages are of two types-

i) Anulom Marriage between male of a higher caste and female of a lower caste. It is valid.

ii) Protilom Marriage between male of a lower caste and female of a higher caste. It is invalid.

Swapinda relationship and marriage-

It is prohibited. It may arise in both Agnate and Cognate relations.

Mitakshara- Marriage is not allowed in blood relations.

Dayabhaga- Marriage is not allowed among those who can offer Pindas.

But if someone marries in Swapinda, it will be considered valid.

Guardianship in marriage-

It is necessary to have guardians in a Hindu marriage.

List of guardians-

Mitakshara school-

i) Father

ii) Paternal grandfather

iii) Brother

iv) Other paternal relation of bride in order of proximity (uncle, cousin)

v) Mother

Dayabhaga school-

i) Father

ii) Paternal grandfather

iii) Brother

iv) Other paternal relation of bride in order of proximity (uncle, cousin)

v) Mother

vi) Maternal grandfather

vii) Maternal uncle

viii) Mother

Polygamy is allowed in Hindu law but Polyandry (polygamy in which a woman has more than

one husband) is not allowed. Some states of India prohibit polygamy.

Marriage is indissoluble. Divorce is not allowed at all.

I n widow remarriage there is conflict-

According to Manu- It is not allowed because 2nd husband of a pious lady is not to be found

anywhere.

But a woman can remarry in five situations-

i) Husband is unheard of

ii) Husband is deaf

iii) Husband becomes ascetic (Nastik)

iv) Impotent

v) Out caste

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

What is the difference between Divorce and Judicial Separation?

Divorce vs Judicial Separation

A Decree Absolute of Divorce brings a marriage to an end and Judicial Separation does

not. However, it is more than a husband and wife living apart. A Decree of Judicial Separation can

be sought on of the five facts which are available for divorce but it is not necessary to prove that the

marriage has irretrievably broken down.

In Divorce there are two Decrees; Decree Nisi and Decree Absolute. In Judicial Separation there is

one Decree pronouncing Judicial Separation. The parties remain married and are therefore not able

to remarry. The Court is able to make the range of financial order which are available on Divorce

save for Pension Sharing or Pension Attachment Orders. The Decree of Judicial Separation has

the same effect as a Decree Absolute of Divorce upon a Will. The spouse can no longer take any

benefit under the Will unless there is a new Will specifically stating they are to do so.

Petitions for Judicial Separation are very rare but there may be reasons for a party seeking this

rather than a Divorce such as one or both of them having religious beliefs or the parties not having

been married for the requisite one year required for a Divorce.

---------------------------------------------------

Hindu Marriage Act 1955

The following is a summary of the Hindu Marriage Act 1955, which aims to allow a

reader to understand the key points within the Act without having to read the Act itself.

Introduction

India, being a cosmopolitan country, allows each citizen to be governed

under personal laws relevant to religious views. This extends to personal laws inter

alia in the matter of marriage and divorce.

As part of the Hindu Code Bill, the Hindu Marriage Act was enacted by Parliament in

1955 to amend and to codify marriage law between Hindus. As well as regulating the

institution of marriage (including validity of marriage and conditions for invalidity), i t

also regulates other aspects of personal life among Hindusand the applicabilityof such

lives in wider Indian society.

The Hindu Marriage Act provides guidance for Hindus to be in a systematic

marriage bond. It gives meaning to marriage, cohabiting rights for both the bride

and groom, and a safety for their family and children so that they do not suffer from

their parental issues.

Applicability

The Act applies to all forms of Hinduism (for example, to a person who is a Virashaiva,

a Lingayat or a follower of the Brahmo, Prarthana or AryaSamam) and also recognises

offshoots of the Hindu religion as specified in Article 44 of the Indian Constitution.

Notably, these include Jains and Buddhists. The Act also applies to anyone who is a

permanent resident in the India who is not Muslim, Jew, Christian, or Parsi by religion.

Although the Act originally applied to Sikhs as well, the AnandKarj Marriage Act gives

Sikhs their own personal law related to marriage.

Although the Act originally did not apply to citizens in the State of Jammu and

Kashmir, the effect of the J&K Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 made it applicable.

Conditions for marriage

Section 5 of The Hindu Marriage Act specifies that conditions must be met for a

marriage to be able to take place. If a ceremony takes place, but the conditions are

not met, the marriage is either void by default, or voidable.

Void marriages

A marriage may be declared void if it contravenes any of the following:

1. Either party is under age.The bridegroom should be of 21 years of age and the bride of 18 years.

2. Either party is not of a Hindu religion.Both the bridegroom and the bride should be of the Hindu

religion at the time of marriage.

3. Either party is already married. The Act expressively prohibits polygamy. A marriage can only be

solemnized if neither party has a living spouse at the time of marriage.

4. The parties are sapindas or within the degree of prohibited relationship.

Voidable marriages

A marriage may later be voidable (annulled) if it contravenes any of the following:

1. Either party is impotent, unable to consummate the marriage, or otherwise unfit for the

procreation of children.

2. One party did not willingly consent. In order to consent, both parties must be sound of mind and

capable of understanding the implications of marriage. If either party suffers from a

mental disorder or recurrent attacks of insanity or epilepsy, then that may indicate that consent

was not (or could not be) given. Likewise, if consent was forced or obtained fraudulently, then the

marriage may be voidable.

3. The bride was pregnant by another man other then the bridegroom at the time of the marriage.

Ceremonies

Section 7 of the Hindu Marriage Act recognises that there may be different, but equally

valid ceremonies and customs of marriage. As such, Hindu marriage may be

solemnized in accordance with the customary rites and ceremonies of either the bride

or the groom. These rites and ceremonies include the Saptapadi and Kreva.

Registering a marriage

A marriage cannot be registered unless the following conditions are fulfilled:

1. a ceremony of marriage has been performed; and

2. the parties have been living together as husband and wife

Additionally,the parties must have been residing within the district of the Marriage

Officer for a period of not less than thirty days immediately preceding the date on

which the application is made to him for registration.

Section 8 of the Hindu Marriage Act allowsastate government to make rules for the

registration of Hindu marriages particular to that state, particularly with respect to

recording the particulars of marriage as may be prescribed in the Hindu Marriage

Register.

Registration provides written evidenceof marriage. As such, the Hindu Marriage

Register should be open for inspection at all reasonable times (allowing anyone to

obtain proof of marriage) and should be admissible as evidence in a court of law.

Divorce

Although marriage is held to be divine, the Hindu Marriage Act does permit either

party to divorce on the grounds of unhappiness, or if he or she can prove that the

marriage is no longer tenable.

A petition for divorce usually can only be filed one year after registration. However, in

certain cases of suffering by the petitioner or mental instability of the respondent, a

court may allow a petition to be presented beforeone year.

Grounds for divorce

A marriage may be dissolved by a court order on the following grounds:

1. Adultery - the respondent has had voluntary sexual intercourse with a man or a woman other

than the spouse after the marriage.

2. Cruelty - the respondent has physically or mentally abused the petitioner.

3. Desertion - the respondent has deserted the petitioner for a continuous period of not less than

two years.

4. Conversion to another religion - the respondent has ceased to be a Hindu and has taken

another religion.

5. Unsound mind - the respondent has been diagnosed since the marriage ceremony as being

unsound of mind to such an extent that normal married life is not possible.

6. Disease - the respondent been diagnosed with an incurable form of leprosy or has venereal

disease in acommunicable form.

7. Presumption of death - the respondent has not been seen alive for seven years or more.

8. No resumption of cohabitation after a decree of judicial separation for a period of at least

one year.

In addition, a wife may also seek a divorce on the grounds that:

1. In case of marriagesthat took place before the Hindu Marriage Act 1955 was enacted, the

husband was already marriedand that any other wife of thehusband was alive at the time of the

marriage ceremony.

2. The husband, after marriage, has been found guilty of rape, sodomy or bestiality.

3. Co-habitation has not been resumed within a yearafter an order for maintenance under Section

125 of the Criminal Procedure Code or alternatively, under the Hindu Adoptions & Maintenance

Act 1956.

4. The wife was under-age when she married and she repudiates the marriage before attaining

the age of 18 years.

Alimonies (permanent maintenance)

At the time of the decree of divorce or at any subsequent time, the court may decide

that one party should pay to the other an amount for maintenance and support. This

could be a one off payment, or a periodical (such as monthly) payment. The amount to

be paid is at the discretion of the court.

Remarriage

Remarriage is possible once a marriage has been dissolved by a decree of divorce

and no longer able to be appealed (whether there was no right of appeal in the first

place, or whether the time for appealing has expired, or whether an appeal has been

presented but dismissed).

-------------------------------------------------------------

SECTION 10 HINDU MARRIAGE ACT

Judicial separation is an instrument devised under law to afford some time for

introspection to both the parties to a troubled marriage. Law allows an opportunity to both

the husband and the wife to think about the continuance of their relationship while at the

same time directing them to live separate, thus allowing them the much needed space and

independence to choose their path.

Judicial Separation and Divorce in India as perHindu Marriage Act

Judicial separation is a sort of a last resort before the actual legal break up of

marriage i.e. divorce. The reason for the presence of such a provision under Hindu

Marriage Act is the anxiety of the legislature that the tensions and wear and tear of every

day life and the strain of living together do not result in abrupt break up of a marital

relationship. There is no effect of a decree for judicial separation on the subsistence and

continuance of the legal relationship of marriage as such between the parties. The effect

however is on their co-habitation. Once a decree for judicial separation is passed, a husband

or a wife, whosoever has approached the court, is under no obligation to live with his / her

spouse .

The provision for judicial separation is contained in section 10 of the Hindu Marriage

Act, 1955. The section reads as under:

A decree for judicial separation can be sought on all those ground on which decree for

dissolution of marriage, i.e. divorce can be sought.

Hence, judicial separation can be had on any of the following grounds:

1. Adultery

2. Cruelty

3. Desertion

4. Apostacy (Conversion of religion)

5. Insanity

6. Virulent and incurable form of leprosy

7. Venereal disease in a communicable form

8. Renunciation of world by entering any religious order

9. Has not been heard of as being alive for seven years

If the person applying for judicial separation is the wife, then the following grounds are

also available to her:

1. Remarriage or earlier marriage of the husband but solemnised before the

commencement of Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, provided the other wife is alive at the

time of presentation of petition forjudicial separation by the petitioner wife.

2. Rape, sodomy or bestiality by the husband committed after the solemnization of his

marriage with the petitioner.

3. Non-resumption of co-habitation between the parties till at least one year after

an award of maintenance was made by any court against the husband and in favour of

the petitioner wife.

4. Solemnization of the petitioner wifes marriage with the respondent husband before

she had attained the age of 15 years provided she had repudiated the marriage on

attaining the age of 15 years but before attaining the age of 18 years.

It is on all the above grounds that judicial separation can be sought. The first 9

grounds are available to both the husband and the wife but the last four grounds are

available only to the wife. It is to be noted that it is on these grounds that divorce is also to

be granted. It has been held that unless a case for divorce is made out, the question of

granting judicial separation does not arise. Therefore, the Courts while dealing with the

applications for judicial separation shall bear in mind the specific grounds raised for grant

of relief claimed and insist on strict proof to establish those grounds and shall not grant

some relief or the other as a matter of course. Thus on a petition for divorce, the Court has

discretion in respect of the grounds for divorce other than those mentioned in section 13

(1A) and also some other grounds to grant restricted relief of judicial separation instead of

divorce straightway

if it is just having regard to the facts and circumstances.

Another question that arises is of decree of maintenance vis--vis decree for judicial

separation. Where a decree for judicial separation was obtained by the husband against her

wife who had deserted him, the wife not being of unchaste character nor her conduct being

flagrantly vicious, the order of alimony made in favour of the wife was not interfered with by

the Court.

ILR (1964) 2 Punj 732.

The Punjab and Haryana High Court has also held that a reading of sec 24 and 26

(maintenance) does not show that if a petition under section 9, 10 12 or 13 is disposed of,

the jurisdiction of the court to award maintenance pendent lite by an order to be passed is

taken away.

AIR 1981 Punj 305 ; 1981 Hindu LR 345

The above decisions go on to show that even where a decree for judicial separation is passed

in favour of the husband, maintenance may still be awarded to a wife and judicial separation

is no defence to a claim for maintenance under Hindu Marriage Act.

Though section 10 of the Hindu Marriage Act does not provide any time as to how long

judicial separation can last. But section 13 of the Act provides that if there is no resumption

of co-habitation between the parties one year after the decree for judicial separation is

passed, the parties can get a decree for divorce on this ground itself. But divorce on this

ground will be given only when one year has expired after the passing of the decree for

judicial separation and not earlier. The reason for this is that one year is a long period and it

provides sufficient time to the parties for reconciliation or to arrive at a decision. If the

parties fail to overcome their differences within this period, then there is no fun in allowing

the legality of the marriage to just linger on when in substance the relationship of marriage

has long expired.

It is to be noted, however, that if the parties do agree to resume co-habitation any time after

the passing of the decree for judicial separation, they can get the decree rescinded by

applying to the court. The Act does not refer to any specific grounds on which a decree for

judicial separation can be annulled or rescinded. Section 10(2) however, empowers the

Court to rescind the decree for judicial separation if it considers it just and reasonable to

do so. However Courts have repeatedly warned that this power of rescission has to be

exercised with great circumspection and not in a hurry and only after satisfying themselves

that it would be just and reasonable to allow such rescission.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Augustinian Liturgy of The HoursDocument163 pagesAugustinian Liturgy of The HoursAdoremus DueroPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.OKANRAN OGBE 15 Files Merged PDFDocument152 pages1.OKANRAN OGBE 15 Files Merged PDFregis67% (3)

- Secret-Doctrine of The Ancient - Russ Michael PDFDocument173 pagesSecret-Doctrine of The Ancient - Russ Michael PDFWarrior Soul100% (5)

- Moot Memorial FormatDocument7 pagesMoot Memorial FormatStuti Baradia100% (1)

- Ankita AgrawalDocument39 pagesAnkita AgrawalStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Document 1Document4 pagesDocument 1Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- A On "Future Prospects of Disabled Children With Respect To: NGO Project ReportDocument40 pagesA On "Future Prospects of Disabled Children With Respect To: NGO Project ReportStuti Baradia100% (3)

- School of Commerce Management and Research: ITM University, Naya Raipur (C G)Document3 pagesSchool of Commerce Management and Research: ITM University, Naya Raipur (C G)Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Document 1Document4 pagesDocument 1Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Law ProjectDocument18 pagesLand Law ProjectStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Public International Law ProjectDocument14 pagesPublic International Law ProjectVishalPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study 5Document2 pagesCase Study 5Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study 2Document3 pagesCase Study 2Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Law ProjectDocument18 pagesLand Law ProjectStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Project PIL ImportanceDocument54 pagesProject PIL ImportanceStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- CS-II Hadr Copy Submission 8th SemDocument12 pagesCS-II Hadr Copy Submission 8th SemStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Law ProjectDocument18 pagesLand Law ProjectStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Law SyllabusDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Law SyllabusStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Banking Law Assignmnts Ques & CasesDocument1 pageBanking Law Assignmnts Ques & CasesStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental LawDocument17 pagesEnvironmental LawStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Part PgsDocument6 pages1st Part PgsStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Law ProjectDocument18 pagesLand Law ProjectStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Project PIL ImportanceDocument54 pagesProject PIL ImportanceStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignmnt 2Document3 pagesAssignmnt 2Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- DPC PRJCT 9th SemDocument8 pagesDPC PRJCT 9th SemStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignmnt 4Document12 pagesAssignmnt 4Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignmnt 1Document3 pagesAssignmnt 1Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Law On Education - Questions For Ass, Cases & CresDocument1 pageLaw On Education - Questions For Ass, Cases & CresStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment - 3 Submitted To: Mr. Purushottam Kumar Subject: Banking Law Submitted By: Stuti Baradia Sem VIII (4 Year) B.B.A LL.BDocument3 pagesAssignment - 3 Submitted To: Mr. Purushottam Kumar Subject: Banking Law Submitted By: Stuti Baradia Sem VIII (4 Year) B.B.A LL.BStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Product Lifecycle: Principles of Marketing MangementDocument13 pagesProduct Lifecycle: Principles of Marketing MangementStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- IPR Cre-3 - Patent Appln, SpecificationDocument9 pagesIPR Cre-3 - Patent Appln, SpecificationStuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Patent Application Form WordDocument5 pagesIndian Patent Application Form WordStuti Baradia100% (1)

- Registration Form 3Document2 pagesRegistration Form 3Stuti BaradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Islamic Religious MusicDocument22 pagesIslamic Religious MusicTiago SousaPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Youth Ministry by Linhart & Livermore, ExcerptDocument38 pagesGlobal Youth Ministry by Linhart & Livermore, ExcerptZondervan100% (1)

- Gloria: VivaldiDocument12 pagesGloria: VivaldiAnder DubiniackPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter of Valenciano Case DigestDocument1 pageLetter of Valenciano Case DigestBiyaya BellzPas encore d'évaluation

- A Reflection On Paulo FreireDocument3 pagesA Reflection On Paulo FreireGellikimPas encore d'évaluation

- Proof. .Illuminati - Planned.to - Bring.down - Our.culture..1.of.5Document14 pagesProof. .Illuminati - Planned.to - Bring.down - Our.culture..1.of.5jrodPas encore d'évaluation

- Saved But Still EnslavedDocument20 pagesSaved But Still EnslavedChosen Books100% (7)

- Table of Specifications - Second Grading PeriodDocument2 pagesTable of Specifications - Second Grading PeriodDanilo Siquig Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lukan VoicesDocument51 pagesLukan VoicesBill CreasyPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 4Document22 pagesUnit 4gcorreabPas encore d'évaluation

- Hamlet Act 4 JournalDocument1 pageHamlet Act 4 JournalPatrick JudgePas encore d'évaluation

- Off Ginuts: Oakland, California, Monday, September 17, 1894. Number 45Document16 pagesOff Ginuts: Oakland, California, Monday, September 17, 1894. Number 45Luis TitoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Review of Mosque ArchitectureDocument4 pagesA Review of Mosque ArchitectureAzii Gluberry Azii GluberryPas encore d'évaluation

- EngDocument11 pagesEngnadi_nadeemPas encore d'évaluation

- Merry Christmas MR Bean: See How Many of These Questions You Can Answer After Watching The First SceneDocument4 pagesMerry Christmas MR Bean: See How Many of These Questions You Can Answer After Watching The First SceneNiki HubertPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Ignatius of Loyola, Spanish San Ignacio de LoyolaDocument4 pagesSt. Ignatius of Loyola, Spanish San Ignacio de LoyolaAustinPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy of AmbedkarDocument21 pagesPhilosophy of AmbedkarmuanPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Eastern ArtDocument30 pagesHistory of Eastern Artmohan50% (2)

- Eucharist Thesis StatementsDocument5 pagesEucharist Thesis StatementsBonirie Tabada RosiosPas encore d'évaluation

- Samuel Adams The Last Puritan Fights The American Revolution TwiceDocument3 pagesSamuel Adams The Last Puritan Fights The American Revolution TwiceLuke HanscomPas encore d'évaluation

- Venetians Took Over England and Created Freemasonry..s Took Over England and Created Freemasonry..Document11 pagesVenetians Took Over England and Created Freemasonry..s Took Over England and Created Freemasonry..HANKMAMZERPas encore d'évaluation

- Weitzmannt - The Icon Holy Images - Sixth To Fourteenth CenturyDocument140 pagesWeitzmannt - The Icon Holy Images - Sixth To Fourteenth CenturyGülşah Uslu67% (3)

- Euch - 3 EasterDocument4 pagesEuch - 3 EasterLoki PagcorPas encore d'évaluation

- 2ND Sunday of AdventDocument171 pages2ND Sunday of AdventPeter Paul HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- G1-TOUTES-FAC-2016-2017-Site 2Document294 pagesG1-TOUTES-FAC-2016-2017-Site 26rsdxhz6dqPas encore d'évaluation

- Tattva Bodhah SP PDFDocument311 pagesTattva Bodhah SP PDFulka123Pas encore d'évaluation

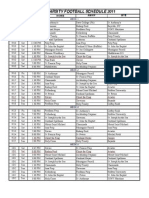

- Schedules 11Document2 pagesSchedules 11api-25130792Pas encore d'évaluation