Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Reid, Ruhanen & Johnston - Untangling The Messy Legislative Basis of Tourism Development Planning - Five Cases From Australia

Transféré par

Gerson Godoy RiquelmeTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Reid, Ruhanen & Johnston - Untangling The Messy Legislative Basis of Tourism Development Planning - Five Cases From Australia

Transféré par

Gerson Godoy RiquelmeDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

This article was downloaded by: [190.82.172.

166]

On: 01 February 2013, At: 10:57

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Anatolia: An International Journal of

Tourism and Hospitality Research

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rana20

Untangling the messy legislative basis

of tourism development planning: five

cases from Australia

Sacha Reid

a

, Lisa Ruhanen

b

& Nicole Johnston

a

a

Department of Tourism, Leisure, Hotel and Sport Management,

Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD, 4222, Australia

b

The School of Tourism, The University of Queensland, Brisbane,

QLD, 4072, Australia

Version of record first published: 14 Aug 2012.

To cite this article: Sacha Reid , Lisa Ruhanen & Nicole Johnston (2012): Untangling the messy

legislative basis of tourism development planning: five cases from Australia, Anatolia: An

International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23:3, 413-428

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2012.714791

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation

that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any

instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary

sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or

indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Untangling the messy legislative basis of tourism development

planning: ve cases from Australia

Sacha Reid

a

*, Lisa Ruhanen

b

and Nicole Johnston

a

a

Department of Tourism, Leisure, Hotel and Sport Management, Grifth University, Gold Coast,

QLD, 4222, Australia;

b

The School of Tourism, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072,

Australia

(Received 23 December 2011; nal version received 19 July 2012)

This article reports on a scoping study examining the legislative basis for tourism

development and planning in Australia. While planning is vital to facilitate strategic

decision-making regarding the appropriate nature and scale of tourism-related

developments within a destination, the legislative frameworks that provide for, control

and regulate many aspects of tourism development have neither been identied nor

collated in an integrated manner. This research used a case-study methodology to

examine the range and scope of legislation impacting tourismdevelopment in Australia.

The study identied 285 current Acts that were categorized into ve broad themes. On

the basis of these ndings, a number of recommendations for identication,

collaboration and education regarding the legislative environment have been postulated.

Keywords: legislation; tourism development and planning; case study

Introduction

This scoping study provides an insight into the messy legislative environment impinging

on tourism development and planning within Australia. Australian tourism has set

aggressive tourist growth forecasts through until 2020, with a strategy to almost double

overnight tourist expenditure. To achieve these forecasts, signicant investment in tourism

product quality and development is required. However, the Commonwealth governments

Jackson Report identied that Australias complex array of planning and regulatory

requirements across states and territories deliver a serious disincentive to prospective

tourism investors (Department of Energy, Resources and Tourism [DERT], 2009a, p. 26).

Tkaczynski, Driml, Robinson, and Dwyer (2011) also found that the complexity and length

of approval processes in many jurisdictions were a signicant impediment to tourism

development and investment. It is the multiple and often overlapping legislative

requirements affecting tourism planning and development that are limiting development

applications and implementation (Department of Industry, Tourism & Resources, 2006;

DERT, 2009a, 2009b; Tkaczynski et al., 2011).

While there has been an array of academic research examining tourism planning and

policy contexts (Erkus-O

zturk, 2010; Gunn & Var, 2002; Hall & Page, 2006; Krutwaysho

& Bramwell, 2010; Riddell, 2004), a comprehensive review of legislation that impacts

tourism development has been overlooked. As McGehee, Meng, and Tepanon (2006,

ISSN 1303-2917 print/ISSN 2156-6909 online

q 2012 Taylor & Francis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2012.714791

http://www.tandfonline.com

*Corresponding author. Email: s.reid@grifth.edu.au

Anatolia An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research

Vol. 23, No. 3, November 2012, 413428

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

p. 685) noted, although the importance of legislation in tourism development is

inherently realized among tourism academics and practitioners, there has been limited

research conducted. This article responds to this gap and presents a scoping study of these

issues in the Australian context. Specically the study sought to examine the range of

legislation that impinges on tourism development at the state and federal levels in

Australia. A case-study approach in ve settings was used to explore and illustrate in

practice the complex, often messy interactions, and competing legislative environments

affecting tourism development. While governments at all levels will need to work with

tourism industry operators to implement the strategy and monitor progress (Department

of Resources, Energy & Tourism, 2011, p. 1), a number of impediments to tourism

development and planning were identied. These impediments provide a framework for

dialogue and regulatory reform to facilitate more effective tourism development.

Literature review

Planning is a future visioning initiative that incorporates designing for the future by

exploringconsequences before makingchoices (Healey, 2009). Hall andPage (2006, p. 321)

note, planning for tourism occurs in a number of forms (development, infrastructure,

promotion and marketing), structures (different government and non-governmental

organizations), scales (international, national, regional, local, sectoral) and times (different

time scales for development, implementation and evaluation). However, planning for

tourism has been advocated by many in response to the negative impacts that can arise for

host destinations from tourism activity. As Riddell (2004, p. 178) notes:

unplanned and under-regulated tourism expansion, with little thought or heed for the

wellbeing of the actual environment, the actual heritage, the actual communities being visited,

or indeed the actual tourists enjoyment, will wear down the very attractions on which the

industry is predicated.

Sentiments echoed by many authors who note that the failure to proactively plan for the

nature and scope of tourism development has left many destinations with a legacy of social

and environmental problems (Fredline, Deery, & Jago, 2005; Gu & Wong, 2006; Haley,

Snaith, & Miller, 2005; Murphy & Murphy, 2004; Northcote & Macbeth, 2005; Tovar &

Lockwood, 2008).

Contemporary planning is increasingly encompassing a wider range of considerations,

including environmental protection, commercial and corporate interests, and public

opinion (Dredge, 1999). This shift can also be seen in approaches to tourism planning

where a holistic systems approach has evolved (Gunn & Var, 2002). The holistic approach

noted by Gunn and Var (2002) can be attributed to the emergence and adoption of the

sustainable development concept and its widespread integration into tourism planning

activities. However as McCool (2009, p. 136) identies, tourism planning occurs in

messy contexts where the sector and markets are continually changing, goals conict

and causeeffect relationships are uncertain. It is evident that tourism development and

planning activities are undertaken for destinations, which are in fact complex systems of

public- and private-sector interests, coupled with host communities, the natural and built

environment and broader sociopolitical frameworks. Therefore, a challenge for planners

and legislators is balancing the often incongruent goals of tourism development with

planning for unknowable circumstances.

Tosun (2001) highlighted that the goals and objectives enacted within legislation have

a signicant inuence on tourism development. In Turkey, for example, goals for

increasing both supply- and demand-side aspects of tourism development resulted in

414 S. Reid et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

channeling generous tourism incentives to pre-determined tourism regions, tourism areas

and tourism centres (Tosun, 2001, p. 295). Tosun (2001) noted that a traditionally

powerful bureaucracy that dominates legislative and operative processes, coupled with

weak industry networks, has resulted in the absence of integrated planning approaches and

unbalanced spatial tourism development. The review of tourism planning in Spain by

Baidal (2004) also concluded that there was a need for processes and preparation of land-

use plans for tourism to be more agile, involving integration from administrators, to ensure

initiatives can be implemented by industry.

However, Erkus-O

zturk (2010, p. 120) stated that, tourismplanning should not be only

in the hands of the central government and some private entrepreneurs (who have strong

relations with central government), but also be in the hands of civil society and other local

actors. Considering a range of stakeholders perspectives and visions spreads the power,

broadening the responsibilities for tourismplanning. Collaborative planning ideally tries to

achieve consensus, not solving all conicts, through decision-making (Bramwell &

Sharman, 1999). Yet such planning approaches have limitations in practice as they fail to

achieve consensus through fair and open processes due to deep-seated vested interests of

participants (Jones, Glasson, Wood, & Fulton, 2011). Nevertheless, it is pertinent, as the

expectations of participants need to be managed, so that implementation of the planning

process occurs. Increasing community collaboration or involvement in this planning

process is integral as those implementing plans are often local ofcials and participants.

As the examination of policy implementation in Phuket, Thailand, by Krutwaysho and

Bramwell (2010, p. 686) found implementation was shown to involve interaction between

different public agencies and tiers of government, who held distinct views about the policies

and their application.

Against this background it has been recognized that tourism activity and development

should be planned for in an integrated and collaborative way to ensure the destination

sustains tourist satisfaction, positive economic benets, and minimal negative impacts on

the local social and physical environments. However, challenges arise for planners as the

decisions they make are nuanced and have to balance idealism [what ought to happen by

and for society] with pragmatism [what can happen with private sector investment]

(Burns, 2004, p. 27). A lack of understanding of the range of sociopolitical inuences on

tourism development and planning exercises is evident. King, McVey, and Simmons

(2000, p. 413) identied a key criticism of tourism planning has been the tendency of

documents to remain as paper exercises, and to sit on government shelves collecting

dust. For plans to be implemented, there is a need for balance idealism and visions with

an understanding of regulations and political factors that inuence tourism development.

The political process in Australia is complicated by multiple levels of governments

exerting varying powers on tourism development.

The Australian legislative environment

Australias tourism sector is complicated with a myriad of organizations and structures

encompassing multiple levels and jurisdictions of government, the private sector and

lobbies, interest groups and industry associations. As Altinay and Bowen (2006, pp. 951

952) note, the governance structure of the country, especially the form of federal

constitution and its institutions, will certainly impact upon the tourism industry and its

environment. Certainly the complex multi-tiered government structure of local, state and

federal authorities in Australia provides a number of challenges in a statutory and legislative

context. For instance, different levels of government tend to have different sets of objectives

Anatolia An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 415

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

to achieve through tourismdevelopment. The messiness occurs for many reasons. One is

that the aims of regional and local governments may diverge from those of federal

government (Hall & Lew, 2009). Also, the myriad of laws and policy areas that impact

tourism, but of which tourismis not the explicit focus, means that tourismis often governed

in an uncoordinated manner whereby tourismissues and policies are disjointedly addressed

(Dredge & Jenkins, 2007; Hall, Jenkins, & Kearsley, 1997; McGehee et al., 2006).

Furthermore, due to the multi-sectoral nature of the industry, tourism impedes on multiple

areas and policy jurisdictions thus simultaneously causing issues in terms of duplication of

aims, objectives and responsibilities (Altinay & Bowen, 2006; Ruhanen, 2006).

Even though Australias Constitution does not explicitly refer to tourism, the federal

government has many powers in respect to regulating areas that inuence tourism,

including world heritage, the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), building codes, airports and

infrastructure, among others. However, challenges arise as the structure of the Australian

government system and the statutory status of federal and state/territory tourism

organizations means that tourism has little to no place, nor involvement, in the

development of laws and regulations that affect the sector. Government agencies often

overlook the issue of tourism when addressing their own industry-related matters and

developing policies (Edgell, DelMastro Allen, Smith, & Swanson, 2008; Gunn & Var,

2002), either intentionally or inadvertently for a number of reasons. For example, an

agency may have differing political agendas and priorities, or a lack of awareness for

tourism and the impact the activity may have on the tourism sector (Dickman, 1998;

Edgell et al., 2008; Urbis & Tourism & Transport Forum, 2011). Owing to the lack of

denitive powers at a national, state or local level, the tourism sector is therefore heavily

reliant on coordination mechanisms that are typically voluntary in nature and as such not

enforceable (Dickman, 1998).

Much of the broader regulatory responsibility for the many areas that impact on

tourism is held by state governments. State government is responsible for a number of

tourism planning activities such as facility development and major infrastructure; and like

the federal government, tourism marketing and promotion (Jenkins & Hall, 1997;

Ruhanen, 2006). Each state and territory also has a state tourism organization (STO) that is

primarily responsible for marketing and promotion at state or territory level (see Table 2).

However, state governments can divest specic legislative powers to local governments,

namely for activities such as local land-use planning and development activities, such as

the provision of local infrastructure and facilities. As a result, local governments also play

a key role in the regulation of tourism-related land uses and have considerable inuence

over the growth and management of tourism at a destination level (Dredge & Jenkins,

2007). For instance, local government is responsible for the approval of tourism

development applications (Ruhanen, 2006; Thompson, 2007). However, state and federal

governments still have the power to review and overrule planning decisions made by local

governments (Dickman, 1998; Dredge & Jenkins, 2007; Thompson, 2007).

Given the previously mentioned challenges associated with multi-tiered government

involvement in tourism development and planning in Australia, this article reports on the

rst empirical study undertaken to investigate the range and scope of federal and

state/territory legislation that impinges on tourism development and planning. While it is

reasonably well accepted that the legislative environment affecting tourismdevelopment is

broad and complex, there have been no previous attempts to catalogue and quantify just how

extensive this issue is (McGehee et al., 2006; Reid, Ruhanen, Davidson, & Johnson, 2010).

While the ndings of this scoping study are unique to Australia, they can provide insights for

other countries as to the plethora of legislation impinging on the tourismsector. Practically,

416 S. Reid et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

the identication of such legislation can assist the tourism industry, developers and

government policy makers. First, to develop effective and implementable tourism plans

there is a need to understand the legislative environment within which tourismdevelopment

and planning operates. Second, the gamut of governmental agencies and departments that

inuence tourism development and planning needs to be identied to ensure that cross-

institutional/governmental networks and communication can be fostered. Finally, an

alignment between operational perspectives and governmental policy is required within the

tourism sector to ensure the sustainability of the sector.

Methodology

An inductive research approach was used to address the objective of this study. First,

secondary data were used to undertake an audit of pertinent legislation. Comprehensive

searches of government (federal and state) websites and direct contact with government

representatives informed the collection of this data. The rst stage of data collection

produced a catalogue of federal and state Acts (an Act is dened as legislation that has

been passed through parliament and has been decreed into law through an Act of

Parliament) that impact on or affect tourism development and planning or the tourism

sector generally. The audit also identied relevant regulatory agencies. It should be noted

that the Acts included in this research were current as on1 March 2010.

The data were analysed using an iterative thematic content analysis process to determine

the range of legislation impacting on tourism development and planning by jurisdiction

(Yin, 2003). Researchers manually open-coded the data by highlighting the aims and

objectives and writing notes about the impact of the Act on tourism development and

planning. Adata-reduction process then collapsed these codes into a range of themes, which

were selectively coded into ve broad-category themes: land-use planning, environment,

tourismoperations and services, cultural heritage and tourismorganizations. This approach

was used to reduce the greater number of themes into fewer content categories (Neuman,

2003; Weber, 1990). These categories also had a number of secondary themes, as evidenced

in the taxonomy of categories and themes depicted in Table 1.

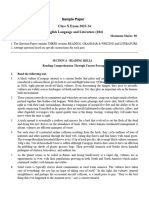

Table 1. Taxonomy of categories and themes.

Category

No. of acts in

category Secondary themes

No. of acts in

theme

Land-use planning 130 Building works and use 45

Infrastructure and transport 43

Land use planning and development 27

Local government 9

Coastal development 6

Environment 89 Marine and sheries 34

Nature conservation 28

Crown land 16

Forestry 11

Tourism operations and 39 Liquor supply and licensing 18

services Casinos and gaming 10

Major events 6

Tourist services 5

Cultural heritage 19 Heritage conservation 11

Indigenous heritage 8

Tourism organizations 8 State tourism organizations 8

Anatolia An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 417

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

Second, a case-study methodology overlaid the secondary data as a means of

examining the messy legislative environment impacting on tourism development and

planning. As Jennings (2001) notes, the advantage of the case-study approach is that in-

depth data are collected and evidenced within a grounded setting. Case studies were

randomly selected to provide geographic spread through Australia and jurisdiction based

on the contexts derived from the key themes of the legislative audit. The case-study

methodology also included a review of key tourism development and planning documents

within the case-study locations. The represented cases studies are the Great Barrier Reef

Marine Park (GBRMP), Docklands, Sydney Olympics, Port Arthur Heritage Site and the

Tourism Tropical North Queensland (TTNQ) organization. The cases do not claim to be

representative, however are signicant in terms of Australian tourism. Combined

GBRMP, Docklands and the Port Arthur Heritage site account for just over 22 million

visitors annually (Docklands, 2012; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

[GBRMPA], 2012; Port Arthur Historic Sites Management Authority, 2012). The Sydney

Olympics, as a mega-event, generated a 15% increase in international visitor numbers

during the corresponding reporting quarter and an additional US$ 2.1 billion in publicity

for Australia (Australian Tourism Commission, 2001). Finally, the region of the Tropical

North Queensland attracted 626,000 international overnight visitors and a further 1.3

million domestic overnight visits in the year ending September 2011, representing 32% of

all international and 8% of all domestic visitors to Queensland (Tourism Queensland,

2011). Importantly, each case draws out the complex legislative environment impacting on

tourism development and planning for these regions, events and/or organizations.

A number of limitations to this research are evident. First, the audit of legislation is

limited to federal and state legislation that broadly impacts on tourism development and

planning. While reference is made to business operation and management, health, taxation

and nancial legislation, a comprehensive review of this legislation is not included in this

research project. Further, there are approximately 560 local government bodies in

Australia (Australian Local Government Association, 2012), therefore completing a

review of local planning processes is beyond the scope of this particular research.

Results

Federal, state and local legislation provides mechanisms for assessment of tourism-related

developments, activities and services. Legislation can facilitate tourism development by

identifying allowable uses, types of development and specic areas, or regions in need of

control or protection. In total 285 Acts were identied, which were coded into ve broad

categories of legislation: land-use planning, environmental, tourism operations and

services, cultural heritage and tourism organizations.

Land-use planning

Land-use planning, as implied, involves planning for the use of land (Priemus, Button, &

Nijkamp, 2007). Development, services and activities (impacting on land) are regulated to

achieve sustainable outcomes, mitigate unintended consequences and shape cities, towns

and regions (Dredge, 2010). Five secondary themes representing 130 federal and state

Acts were identied within the land-use planning category: building works and use,

infrastructure and transport, land-use planning, local government and coastal

development. Further, each Australian state and territory has established a system of

planning under their respective state and local planning regulations. However, it is beyond

the scope of this article to discuss each of these systems here.

418 S. Reid et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

Docklands, adjacent to the Melbourne central business district in the southern

Australian state of Victoria, provides insights into the complex and interdisciplinary

legislative environments impacting on land-use development. This long-term redevelop-

ment project, comprising approximately 700 hectares of former industrial land fronting the

Yarra River, offers a number of precincts (mixed use, commercial, residential, recreational

and touristic). To enable the redevelopment, the City of Melbourne enacted the Docklands

Authority Act 1991 to facilitate whole of site strategic planning and quicker approval

processes. Melbourne City Council, VicUrban and the Docklands Coordination Committee

are responsible for overseeing and coordinating the redevelopment, promoting private-

sector investment, acquiring and disposing of land, levying charges and acting as the referral

authority for the purposes of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. Ordinarily, the

Planning and Environment Act 1987 covers all land-use planning controls administered by

the Victorian state and local government authorities.

Despite the site-specic legislation enabling planning and development consent and

approval, a number of other federal, state and local Acts must be considered. Land use and

development governance decisions are affected by a culmination of a further 11 Acts (i.e.

Carlton (Recreation Ground) Land Act 1966, City of Melbourne Act 2001, Crown Land

(Reserves) Act 1978, Cultural and Recreational Lands Act 1963, Emergency Management

Act 1986, Environmental Protection Act 1970 and 1994, Local Government Act 1989,

Melbourne Lands (Yarra River North Bank) Act 1997, Parks Victoria Act 1998 and the

Subdivision Act 1988). In addition, 11 Acts of transport and infrastructure legislation must

also be considered in the development of the site (i.e. the Building Act 1993, Congestions

Levy Act 2005, Disability Discrimination Act, Infrastructure Australia Act 2008,

Melbourne City Link Act 1995, Port Services Act 1995, Rail Corporations Act 1996, Road

Management Act 2004, Road Safety Act 1986, Transport Act 1983 and the Transport

Integration Act 2010). The former industrial site also has a unique maritime historical

signicance that is protected under the Heritage Act 1995 and the Heritage Rivers Act

1992. The Heritage Rivers Act 1992 legislatively provides for the identication and

protection of heritage, river and natural catchments areas, while prohibiting development

and activities that impair the passage of water, recreational and conservation of these

cultural heritage sites.

The introduction of site-specic legislation to facilitate land-use planning and

development has been evidenced in a number of other jurisdictions including Sanctuary

Cove, a tourism and residential resort development in Queensland (Sanctuary Cove Resort

Act 1985) and the redevelopment of formerly industrial land at Subiaco in Western Australia

(Subiaco Redevelopment Act 1994). Site-specic legislation often results in a centralized

authority or agency being responsible for strategic and integrated planning, as well as for

development consent of newprojects within these sites. However, site-specic Acts remove

local democratic and community consultative processes and input:

In practice, approvals of major development projects sponsored by the Docklands Authority

are, for the most part, carried out by Planning Scheme amendments by the Minister. This does

not provide any avenue for residents of the City of Melbourne or the residents of Docklands to

exercise objection or appeal rights, or to make formal submissions on the amendments, since

they are generally not advertised. (Department for Victorian Communities, 2003, p. 22)

Notwithstanding, there are a range of other Acts that need to be identied and adhered to in

large-scale development sites of this nature. Without the governing authority and

respective regulations, the development may have been in a haphazard and most likely

disjointed manner, thus potentially diminishing its touristic appeal.

Anatolia An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 419

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

Environmental

The research identied 89 environmental- and nature-based legislation Acts that impact on

tourism development. Environmental legislation is context specic, relating to dominate

uses, and dependent on location. For instance Queensland (n 16), Northern Territory

(n 12) and Victoria (n 12) are the most prolic legislators of the environment. The

environmental category included sub-themes relating to nature conservation, forestry,

marine environments and sheries, and crown land. The GBR, covering 347,000 square

kilometres and more than 2600 kilometres of Queensland coastline, provides an

interesting case of the complex nature and scope of legislation impacting on tourism

development and planning.

The GBRMPA was established as a statutory body (an organization or authority set up

by law to administer or enforce legislation on behalf of the relevant government) in 1975

to govern the use of the Marine Park and is regulated in accordance with national

legislation, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Act 1975. Through the implementation of this

destination-specic piece of legislation and the use of a statutory body (GBRMPA), the

Marine Parks unique environmental, cultural, scientic and historical values are catered

for and aspects of management, such as tourism, are more effectively handled. To achieve

this, GBRMPA uses a number of legislative instruments and management systems such as

zoning plans, permits and plans of management (POM).

Zoning areas are a statutory measure introduced to limit access and activities

undertaken in specic areas of the Marine Park. For instance, a General Use Zone permits

a number of reasonable activities such as boating and shing, while a Preservation Zone

allows only limited scientic research. Subsequently, these zoning schemes impact on

tourist activities, such as shing and camping, which are regulated and prohibited in some

areas of the Marine Park (such as Preservation Zones). Permits are required for vessels

operating for charter hire, ferry service or for tourism purposes and certain conditions must

be met. Permits are also a requirement for construction activity and infrastructure

development within the Marine Park. POMs are legislative instruments that set out the

policies and strategies regarding management of the Marine Park. However, these POM

need to take into account other plans made under the Marine Parks Act 2004 and the

Nature Conservation Act 1992.

Although the Great Barrier Reef Marine Act 1975 is the main legislative framework,

numerous other Commonwealth Acts are also applicable to the Marine Park, such as

Environment Protection (Sea Dumping) Act 1981 and the Environment and Protection and

Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. State legislation is also relevant and includes the

Coastal Protection and Management Act 1995, Environmental Protection Act 1994,

Fisheries Act 1994, State Development and Public Works Organization Act 1971 and the

Sustainable Planning Act 2009. Further, the site was World Heritage listed in 1981 and

thus subject to a number of international conventions and treaties relating to its protection.

Despite being managed under the most stringent legislative policies and guidelines,

tourism on the reef still contributes some $6 billion dollars annually to the national

economy (GBRMPA, 2007).

Tourism operations and services

Tourism is a multifaceted sector consisting of a diverse array of interrelated products and

services (Reid et al., 2010). The research identied 39 Acts that inuence tourism

operations and services encompassing four themes: liquor supply and licensing, casino and

gaming, major events and tourist services. Tourism demand and activity stimulates

420 S. Reid et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

demand for other products, services and activities (Edgell et al., 2008). For example, in

addition to local consumption, tourists also generate demand for alcohol and beverages.

Eighteen Acts, representative of all the states and territories, regulate liquor licensing, the

types of licenses available (e.g. hotel, restaurant), the conditions that apply to the license

and the restrictions and therefore penalties that apply for the supply of liquor without the

requisite license.

Major events, such as the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, have also been enabled

through the introduction of event-specic legislation. Events showcase destinations to a

much wider audience than just attendees, therefore are important platforms for tourism

marketing and economic development for governments and tourism organizations

(Dansero & Puttilli, 2010; Hiller, 2006; Jago, Dwyer, Lipman, van Lill, & Vorster, 2010;

Reid, 2008). Furthermore, the range of social consequences that arise for host cities

necessitates that governments introduce legislation as well as complex intergovernmental

collaborations for effective event planning (Gursoy & Kendall, 2006; Horne &

Manzenreiter, 2004). A range of legislation was specically created for the Olympics such

as the Sydney Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games Act 1993 (SOCOG Act).

The SOCOG Act was enacted by the New South Wales (NSW) government to full the

obligations and provisions within the Host City Contract to the International Olympic

Committee (IOC; SOCOG, 2001). The Act outlined the organizing committees

responsibilities for: preparing and operating the sports programme; organizing the cultural

programme; establishing the marketing programme in consultation with the IOC and the

Australian Olympic Committee; and providing host broadcaster, television, radio and

other information services. The Act also made provisions for governance and nancial

accountability, acknowledging the role of various other pieces of legislation, such as the

Public Finance and Audit Act, Annual Reports Act, Freedom of Information Act,

Independent Commission Against Corruption Act, Ombudsman Act and the Sydney 2000

Games Administration Act 2000. The NSW government also created the Olympic Co-

ordination Authority Act 1995 that required the Authority and the Environmental

Guidelines to be considered in all developments. The major venue was legislated with the

creation of the Homebush Bay Operations Act. This Act provided powers to manage and

control the Homebush domain area as the landowner, including the legal consent authority

for building and planning approvals under local-government legislation. Furthermore, the

Olympic Arrangements Act 2000 created temporary legislative measure to make changes

to legislation during the Olympic and Paralympic Games in September and October 2000.

Lessons from previous Olympics ensured that in planning for Sydney 2000 a

coordinated approach to transport was required. To enable this, the NSW government

enacted the legislation Olympic Roads and Transport Authority Act 1998 (ORTA). The

ORTA was established as a body to be able to control, for the benets of the Olympic

Games, the myriad of agencies involved in transport planning and operations in Sydney. In

addition, the Olympic Co-ordination Authority also brought together a range of

government agencies and levels of government through memorandum of understandings.

There was a multitude of other legislative measures enacted to ensure the successful

staging of the Sydney 2000 Olympics. Examples included liquor licensing, health and

pharmaceutical arrangements to name a few. Furthermore, the federal government was

involved in enacting federal legislation, Olympic Insignia Protection Amendment Act 1994

and the Sydney 2000 Games (Indicia and Images) Protection Act 1996, in an attempt to

stop ambush marketing through regulation for commercial use of the images and indicia

associated with the event. It is evident that an event the size of the Olympics creates unique

Anatolia An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 421

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

and complex intergovernmental collaboration, with the creation of legislation enabling

coordination within a timely manner.

Cultural heritage

The audit identied 19 legislative Acts relating to tourism and the management and

protection of Australian cultural heritage. Heritage buildings and monuments, historic

sites and landmarks, and natural environments are unique draw cards for tourists visiting

Australia. One example is a key Australian cultural heritage site, Port Arthur in Tasmania,

which is a surviving example of a nineteenth-century British convict colony. The site is the

most popular Tasmanian tourist attraction, with approximately 255,000 people visiting

each year (Port Arthur Historic Sites Management Authority, 2012). The Port Arthur

Historic Site Management Authority Act (PAHSMA Act) was introduced in 1987 and a

statutory body, the Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, was established to

effectively manage, maintain and control the use of the site.

The Authority has numerous powers that impact on visitors use of the Port Arthur

Historic Site, such as being responsible for permitting, governing and providing various

commercial and tourism-related activities (i.e. selling and hiring of equipment, granting of

leases or licenses to occupy). The PAHSMA Act stipulates that the Authority may

construct, maintain and eliminate roads on the site, with the Authority having constructed

a system of timber and low-impact steel mesh walkways that provide safe and relatively

easy access. In addition, where buildings and areas have been identied as being of a

sensitive heritage nature or pose risk to visitors, access has been restricted. Contributing

signicantly towards the ongoing management, maintenance and preservation of the site,

and ensuring the tourist experience is high quality and authentic, the Act also enables the

Authority to levy and collect fees and charges from visitors (i.e. an admission fee). As the

Authority operates in accordance with the Government Business Enterprises Act 1995,

admission fees are reviewed on an annual basis and adjustments are made in line with

operational requirements. This site also features many valuable items of moveable cultural

heritage including artefacts, convict relics, furniture and rearms. The PAHSMA Act gives

the Authority specic legislative power to ne persons found to be guilty of removing or

damaging any artefact or relic, or ora or timber from the site without approval.

Also a comprehensive statutory framework has been introduced across all levels of

government, which impact the provision of tourism planning and development at the site.

Internationally, the site was awarded World Heritage listing under the Australian Convict

Sites inscription in 2010. This listing ensures that the World Heritage Convention Act 1983

will also apply to the site thus resulting in additional statutory obligations being placed on

the Commonwealth Government. Federally, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity

Conservation Act 1999 protects this site which is registered on the National Heritage List.

The Authority is therefore required to undertake rigorous assessment processes and

implement a management plan. At the state level, the site is recorded on the Tasmanian

Heritage List which is governed in accordance with the cultural heritage legislation, the

Historic Cultural Heritage Act 1995. Both pieces of legislation are designed to protect the

cultural, environmental and heritage values of the site and therefore any proposed

alterations or works that could affect the heritage values of the site require approval from

both the Federal Minister for Environment, Heritage and the Arts and the Tasmanian

Heritage Council. In addition, as land use and development are generally regulated by local

council planning schemes, approval must also be sought from the Tasman Municipal

Council, which is subject to the Land Use Planning and Approvals Act 1993. The PAHSMA

422 S. Reid et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

Act stipulates, however, that the Authority may enter into an arrangement with the local

council to control land use and building activities on the subject site, therefore allowing the

Authority to plan more strategically and effectively for tourism. Other Tasmanian Acts and

policies that the Authority must comply with include: Tasmanian State Coastal Policy 1996,

Local Government Act 1993 and Amendment 1995, Tasman Planning Scheme 1979, State

Services Act 2000, National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002, Aboriginal Relics

Act 1975 and the Nature Conservation Act 2002.

Tourism organization

The nal category identied nine pieces of legislation relating to tourism organizations.

Tourism Australia is the countrys national tourism organization and was established to

. . . boost international marketing, stimulate growth in domestic tourism, particularly in

regional areas, and pursue structural initiatives to assist in the growth of the industry

(Dredge & Jenkins, 2007, p. 252). Similarly, each state and territory has their own tourism

organization (STOs) as depicted in Table 2.

Tourism organizations are statutory authorities that operate independently of

government departments, with the exception of Australian Capital Tourism in the

Australian Capital Territory and the South Australia TourismCommission. STOs generally

have an advisory role in howtourismis planned, developed and managed (Hall et al., 1997).

They also usually provide guidance to industry, regional (sub)level tourism organizations,

government agencies and other stakeholders on tourism development and planning matters

(Dredge &Jenkins, 2007). Ultimately though, these are marketing- and promotion-focused

organizations. Owing to a lack of legislative powers, these organizations have limited

authority to direct other government agencies and departments to meet tourism-specic

objectives (Hall, 2000). Consequently, to inuence tourismplanning outcomes in Australia,

these organizations rely on partnership arrangements and coordination mechanisms

(Dickman, 1998), such as Memorandum of Understandings and tourism plans.

Government tourism organizations, such as STOs and federal departments, regularly

engage in collaborative discussion and strategy development. An example of which is the

Table 2. Australian state and territory tourism departments and organizations.

Jurisdiction State tourism department

State tourism organization

(STOs)

Australian Capital

Territory

Department of Territory and

Municipal Services

Australian Capital Tourism

New South Wales Department of Industry and

Investment

Tourism New South Wales

Northern Territory Department of Business, Economic

and Regional Development

Tourism Northern Territory

Queensland Department of Employment, Economic

Development and Innovation

Tourism Queensland

South Australia South Australia Tourism Commission South Australia Tourism

Commission

Tasmania Department of Economic Development,

Tourism and the Arts

Tourism Tasmania

Victoria Department of Innovation, Industry and

Regional Development

Tourism Victoria

Western Australia Western Australia Tourism Commission

Board

Tourism Western Australia

Anatolia An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 423

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

Achievement by Partnerships: Tourism Collaboration Intergovernmental Arrangement

(Commonwealth of Australia, 2005, p. 7). However, policies such as these highlight the

position that This Arrangement between parties is not legally binding in any way and

does not give rise to legal rights or obligations (Commonwealth of Australia, 2005, p. 7).

In addition, there are various agreements, arrangements and organizations that operate

within the tourism sphere, such as Regional Tourism Organizations (RTOs). RTOs are

responsible for the management and development of tourism within a region to increase

visitation and yield through marketing (Tourism Alliance Victoria, 2008). These

organizations are generally convened under three main legal frameworks; as limited

liability companies under Federal Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), incorporated associations

registered under the Associations Incorporation Acts of respective states and territories or

as special committees under the Local Government Acts of respective states and territories.

For example, TTNQ is the ofcial RTO for Tropical North Queensland region of

Australia, which includes: the GBR, Cairns, Cairns Beaches and Palm Cove, Port Douglas,

Daintree and Cape Tribulation, Cooktown, Cape York Peninsula, the Gulf Savannah,

Kuranda and Cairns Highlands, and Mission Beach. TTNQ is an industry-funded

incorporated private company limited by Guarantee, with all activities overseen by the

TTNQ Board of Directors (Darveniza, 2009).

Conclusion and implications

Investment in tourism development is essential if Australia is to achieve the aggressive

tourist ow forecasts sought over the next 10 years. Governments and industry have

acknowledged that Australias complex planning and regulatory environment provides a

disincentive to potential tourisminvestors (DERT, 2009a; Tkaczynski et al., 2011; Urbis &

Tourism & Transport Forum, 2011). However, to date the legislative environment that

impinges on tourism development and planning has been overlooked within the academic

literature. Research in each of the ve cases indicates that there is an extensive range of

legislation impacting on tourismdevelopment and planning. The signicance and effects of

legislation is unique and context specic. Often, there are multiple jurisdictions and Acts,

which must be considered in tourismdevelopments. The GBRand Port Arthur Historic Site

provide interesting cases of multi-level jurisdictions, from international treaties and World

Heritage listing to federal and state legislation, impacting on tourism development. The

environmental and cultural heritage signicance of these sites has ensured that governments

at all levels have acted to protect the sites through laws and governance mechanisms.

The nature of tourism predicates that discussions about legislation impacting on

tourism development and planning need to be undertaken with a range of government

departments at local, state and federal levels (Dickman, 1998; Dredge & Jenkins, 2007;

Murphy & Murphy, 2004). Previous national tourism strategies such as the Tourism White

Paper outlined, a whole-of-government approach to tourism, aiming at removing

duplications, maximizing opportunities and facilitating partnerships and innovation

(Australian Government, 2004, p. ix). This sentiment was reiterated in the current national

strategy. Being engaged with and aware of the legislative and policy movements within

these different government departments is a signicant challenge facing STOs, industry

associations and lobbyists. Hall (2008) also acknowledges that a whole-of-government

response lies outside the usual jurisdiction of tourism-specic governance. Although

tourism industry councils (such as the Queensland Tourism Industry Council) and the

national Tourism and Transport Forum organization do much in the way of lobbying

government agencies on the importance of tourism, there is still scope to improve and open

424 S. Reid et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

the communication channels between government agencies and STOs to address much of

the ambiguity identied in this research.

Key recommendations emanating from this research are provided to address the

messy legislative environment impacting on tourism development and planning.

Statutory bodies and the industry more generally need to be educated as to the extent to

which tourism is impacted on by various Acts and regulations. Education will ensure that

the directions identied in tourism development and planning exercises have a basis in

current legal frameworks that may go some way towards overcoming the challenges that

tend to arise when implementing tourism plans and strategies. To address this, opportunity

exists within undergraduate and postgraduate tourism degrees, as well as professional

development and management programmes, to incorporate such concepts within the

curriculum to better prepare those entering the public and private sectors of the industry to

understand, and respond to, the impacts of legislation on the sector. Education may also

assist in engaging the range of stakeholders that can be or are affected by tourism

development in the planning phase (Bramwell & Sharman, 1999).

The layering of legislation from differing levels of governance in conjunction with

other policies, not necessarily tourism specic, has a signicant effect on tourism

development and planning (Hall, 2009). This messiness is a signicant factor impeding

tourism development and planning in Australia. Mixed-use redevelopments, such as

Docklands and Subiaco, have demonstrated the effectiveness of site-specic legislation

that provides a governing authority with legislative power for strategic integrated planning

and development decision-making. These powers unburden developers from navigating

the multiple levels and government departments that would otherwise apply. Opportunity

exists within Australia, as many urban and peri-urban sites undergo redevelopment, to

have centralized site-specic development authorities oversee development and planning

assessment. The Urban Land Development Authority (ULDA) in Queensland provides an

example of an organization that works with local and state governments, the development

industry and the community to create best practice urban designed mixed-use

communities. ULDA is responsible for planning and assessing development applications,

thus providing a one-stop point of contact for potential developers.

In addition, further research investment is recommended to identify and interpret the full

range of legislation impacting the tourism sector in Australia. This scoping study was

delimited to federal and state/territory jurisdictions within key legislation categories (i.e.

land-use planning) and as such provides an exploratory review of the myriad of issues.

While all attempts were made to ensure this scoping study was as holistic as possible, the full

range of legislation that impacts on the tourismindustry is certainly larger than the 285 Acts

identied here. Further, the role of local government has been acknowledged as important,

yet it is often overlooked. Additional attention should be given to the impact of federal and

state legislation on the functions and decision-making capacity of local governments with

respect to tourism development and planning. Further research is required to examine the

range and scope of policies and regulations at a local government level.

There is a need, on an ongoing basis, to build on and amend the Australian legislation

database that is an outcome of this study. The creation of an online database or data

warehouse may be coordinated through peak tourism bodies or tourism industry councils.

The need for an online database has been recognized by the United Nations World

Tourism Organization (UNWTO) who developed LEXTOUR in 2002 as an international

referral system facilitating direct access through links to external websites, databases and

information servers on tourism legislative data produced and distributed by authoritative

sources such as parliaments, central government bodies (including National Tourism

Anatolia An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 425

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

Administrations), universities, professional associations, etc. (UNWTO, 2003, p. 1).

Despite attempts to ensure that LEXTOUR remains a reliable source of information in the

process of constructing the Australian database, it was found that the content on the

LEXTOUR database is not comprehensive, dated and extremely difcult to navigate. It is

recommended that a specic database system is developed for Australia and maintained by

one of the aforementioned organizations.

In conclusion, this research provides an attempt to examine the range and scope of

legislation impacting on tourism development and planning. The research identied that

there were ve key categories of legislation: land-use planning, environmental, tourism

operations and services, cultural heritage and tourism organizations. The challenge for the

tourism industry is identifying relevant legislation within each jurisdiction that applies to

potential tourism developments. Decoding this messiness may be achieved through the

creation of a national database that identies legislation by level of government, region

and legislative categories.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the many people who contributed their time and experience to this project, with a

particular note to Professor Michael Davidson and Ms Sarah OGrady. The Sustainable Tourism

Cooperative Research Centre (STCRC), established and supported under the Australian

Government, funded this research. Members of the Industry Reference Group (IRG) are also

thanked for their guidance on this project.

References

Altinay, L., & Bowen, D. (2006). Politics and tourism interface: The case of Cyprus. Annals of

Tourism Research, 33(4), 939956.

Australian Government (2004). Tourism White Paper implementation plan: Achieving platinum

Australia: Implementation plan 2004. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Australian Local Government Association (2012). About ALGA. http://www.alga.asn.au/.

Australian Tourism Commission (2001). Australian tourism commission Olympic Games tourism

strategy. Doi: http://fulltext.ausport.gov.au/fulltext/2001/atc/olympicreview.pdf.

Baidal, J. (2004). Tourism planning in Spain: Evolution and perspectives. Annals of Tourism

Research, 31(2), 313333.

Bramwell, B., & Sharman, A. (1999). Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Annals of

Tourism Research, 26, 392415.

Burns, P.M. (2004). Tourism planning: A third way? Annals of Tourism Research, 31(1), 2443.

Commonwealth of Australia (2005). Achievements by partnerships: Tourism collaboration

intergovernmental arrangement. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Dansero, E., & Puttilli, M. (2010). Mega-events tourism legacies: The case of the Torino 2006

Winter Olympic Games: a territorialisation approach. Leisure Studies, 29(3), 321341.

Darveniza, M. (2009). Dening an economic development model for the Cassowary Coast Regional

Council. http://www.thinktnq.com.au/research/8/9/doc-31.

Department of Energy, Resources and Tourism (2009a). The Jackson report on behalf of the Steering

Committee: Informing the national long-term tourism strategy. Canberra: Commonwealth of

Australia.

Department of Energy, Resources and Tourism (2009b). National long term tourism strategy.

Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources (2006). National tourism investment strategy,

investing in our future. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (2011). Tourism 2020. http://www.tourism.aus-

tralia.com/Tourism_2020_overview.pdf.

Department for Victorian Communities (2003). IDC report on governance of Melbourne Docklands.

http://www.dpcd.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_le/0017/38150/IDC_Report_on_Gov_of_

Melbourne_Docklands_2004_no_4.pdf.

426 S. Reid et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

Dickman, S. (1998). Tourism: An introductory text. Rydalmere: Hodder Education.

Docklands (2012). Docklands retail statement 2008: 2012. http://www.docklands.com/cs/Satellite?

blobcol=urldata&blobheader=application%2Fpdf&blobkey=id&blobtable=MungoBlobs&

blobwhere=1334640050646&ssbinary=true&blobheadername1=Content-Type&blobheader

value1=application/pdf&blobheadername2=Content-Dispostion&blobheadervalue2=attach-

ment%3B+lename%3DDocklandsRetailStatement.pdf.

Dredge, D. (1999). Destination place planning and design. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4),

772791.

Dredge, D. (2010). Place change and tourism development conict: Evaluating public interest.

Tourism Management, 31(1), 104112.

Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2007). Tourism policy and planning. Milton: John Wiley.

Edgell, D.L., DelMastro Allen, M., Smith, G., & Swanson, J.R. (2008). Tourism policy and

planning: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Oxford: Elsevier.

Erkus-O

zturk, H. (2010). Planning of tourism development: The case of Antalya. Anatolia, 21(1),

107122.

Fredline, E., Deery, M., & Jago, L. (2005). Social impacts of tourism on communities. Gold Coast:

Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2007). Great Barrier Reef climate change action plan

20072012. Townsville: GBRMPA.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2012). Great Barrier Reef Marine park tourist visits.

Townsville: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Gu, M., & Wong, P. (2006). Residents perception of tourism impacts: A case study of homestay

operators in Dachangshan Dao, North-East China. Tourism Geographies, 8(3), 253273.

Gunn, C., & Var, T. (2002). Tourism planning: Basics, concepts, cases (4th ed.). London: Routledge.

Gursoy, D., & Kendall, K. (2006). Hosting mega events: Modeling locals support. Annals of

Tourism Research, 33(3), 603623.

Haley, A., Snaith, T., & Miller, G. (2005). The social impacts of tourism: A case study of Bath, UK.

Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79105.

Hall, C.M. (2000). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Hall, C.M. (2008). Tourism planning (2nd ed.). London: Prentice Hall.

Hall, C.M. (2009). Archetypal approaches to implementation and their implications for tourism

policy. Tourism Recreation Research, 34(3), 235245.

Hall, C.M., Jenkins, J., & Kearsley, G. (1997). Tourism planning and policy in Australia and NZ.

Sydney: Irwin Publishers.

Hall, C.M., & Lew, A.A. (2009). Understanding and managing tourism impacts: An integrated

approach. Oxon: Routledge.

Hall, C.M., & Page, S.J. (2006). The geography of tourism and recreation: Environment, place and

space. Oxon: Routledge.

Healey, P. (2009). The pragmatic tradition in planning thought. Journal of Planning Education and

Research, 28, 277292.

Hiller, H. (2006). Post-event outcomes and the post-modern turn: The Olympics and urban

transformation. European Sport Management Quarterly, 6(4), 317332.

Horne, J., & Manzenreiter, W. (2004). Accounting for mega-events: Forecast and actual impacts of

the 2002 Football World Cup Finals on the host countries Japan/Korea. International Review for

the Sociology of Sport, 39(2), 187203.

Jago, L., Dwyer, L., Lipman, G., van Lill, D., & Vorster, S. (2010). Optimising the potential of mega-

events: An overview. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 1(3), 220237.

Jennings, G. (2001). Tourism research. Milton: John Wiley.

Jenkins, J.M., & Hall, C.M. (1997). Tourism planning and policy in Australia. In C.M. Hall, J.M.

Jenkins, & G. Kearsley (Eds.), Tourism planning and policy in Australia and New Zealand:

Cases, issues and practice (pp. 3748). Sydney: Irwin.

Jones, T., Glasson, J., Wood, D., & Fulton, E. (2011). Regional planning and resilient futures:

Destination modeling and tourism development: The case of the Ningaloo Coastal region in

Western Australia. Planning Practice and Research, 26(4), 393415.

King, B., McVey, M., & Simmons, D. (2000). A societal marketing approach to national tourism

planning: Evidence from the South Pacic. Tourism Management, 21(4), 407416.

Krutwaysho, O., & Bramwell, B. (2010). Tourism policy implementation and society. Annals of

Tourism Research, 37(3), 670691.

Anatolia An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 427

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

McCool, S. (2009). Constructing partnerships for protected area tourism planning in an era of change

and messiness. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(2), 133148.

McGehee, N., Meng, F., & Tepanon, Y. (2006). Understanding legislators and their perceptions of

the tourism industry: The case of North Carolina, USA, 1990 and 2003. Tourism Management,

27(4), 684694.

Murphy, P., & Murphy, A. (2004). Strategic management for tourism communities: Bridging the

gaps. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

Neuman, W. (2003). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (5th ed.).

Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Northcote, J.K., & Macbeth, J. (2005). Limitations of resident perception surveys for understanding

social impacts: The need for triangulation. Tourism Recreation Research, 30(2), 3950.

Port Arthur Historic Sites Management Authority (2012). Port Arthur historic site management

authority 20102011 annual report. http://www.portarthur.org.au/le.aspx?id=14651%20.

Priemus, H., Button, K., & Nijkamp, P. (2007). Land use planning. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Reid, S. (2008). Identifying social consequence of rural events. Event Management, 11(12),

8998.

Reid, S., Ruhanen, L., Davidson, M., & Johnson, N. (2010). Legal basis of state and territory tourism

planning. Gold Coast: Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre.

Riddell, R. (2004). Sustainable urban planning: Tipping the balance. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Ruhanen, L. (2006). Sustainable tourism planning: An analysis of Queensland local tourism

destinations (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Sydney Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (2001). Preparing for the games: Ofcial

report of the XXVII Olympiad. Canberra: Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic

Games.

Thompson, S. (2007). Planning Australia: An overview of urban and regional planning. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Tkaczynski, A., Driml, S., Robinson, J., & Dwyer, L. (2011). Impediments to tourism development

in Australia: A scoping study. Tourism Review International, 14(23), 117128.

Tosun, C. (2001). Challenges of sustainable tourism development in the developing world: The case

of Turkey. Tourism Management, 22, 289303.

Tourism Alliance Victoria (2008). Functions of a regional tourism organization: Fact sheet 05. East

Melbourne: Tourism Alliance Victoria.

Tourism Queensland (2011). Tropical North Qld regional snapshot. http://www.tq.com.au/fms/tq_

corporate/research/destinationsresearch/tropical_north_qld/11%20September%20Regional%

20Snapshot%20Tropical%20North%20Queensland.PDF.

Tovar, C., & Lockwood, M. (2008). Social impacts of tourism: An Australian regional case study.

International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(4), 365378.

United Nations World Tourism Organization (2003). About the tourism legislation database

(LEXTOUR). http://www.unwto.org/documentation/lextour/en/lextour.php?op=1&subop=2.

Urbis and Tourism and Transport Forum (2011). National tourism planning guide a best practice

approach. Canberra: Australian Government and Australia Unlimited.

Weber, R. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd ed.). Newbury Park: Sage.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Designs and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

428 S. Reid et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

9

0

.

8

2

.

1

7

2

.

1

6

6

]

a

t

1

0

:

5

7

0

1

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

2

0

1

3

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grez Sergio - Salvador Allende en La Perspectiva Historica Del Movimiento Popular ChilenoDocument1 pageGrez Sergio - Salvador Allende en La Perspectiva Historica Del Movimiento Popular ChilenoGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Ut22084 060 008Document52 pagesUt22084 060 008Gerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- (C) Greenhow Crhistine - Youth, Learning and Social MediaDocument9 pages(C) Greenhow Crhistine - Youth, Learning and Social MediaGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Barrett Life PhagmodrupaDocument16 pagesBarrett Life PhagmodrupaTùng HoàngPas encore d'évaluation

- (C) Ives Eugenia - IGeneration. The Social Cognittive Efectes of Digital Technology On TeenagersDocument107 pages(C) Ives Eugenia - IGeneration. The Social Cognittive Efectes of Digital Technology On TeenagersGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Sustainable TourismDocument15 pagesJournal of Sustainable TourismGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Pike, Bianchi, Kerr & Patti - Consumers-Based Brand Equity For Australia As A Long Haul Tourism Destination in An Emerging MarketDocument27 pagesPike, Bianchi, Kerr & Patti - Consumers-Based Brand Equity For Australia As A Long Haul Tourism Destination in An Emerging MarketGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Barrett Life PhagmodrupaDocument16 pagesBarrett Life PhagmodrupaTùng HoàngPas encore d'évaluation

- Pomering, Noble & Johnson - Coceptualising A Contemporary Marketing Mix For Sustainable TourismDocument18 pagesPomering, Noble & Johnson - Coceptualising A Contemporary Marketing Mix For Sustainable TourismGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Pike & Mason - Destination Competitiveness Through The Lens of Brand Positioning - The Case of Australia's Sunshine CoastDocument26 pagesPike & Mason - Destination Competitiveness Through The Lens of Brand Positioning - The Case of Australia's Sunshine CoastGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Whittlesea & Owen - Towards A Low Carbon Future - The Development and Application of REAP Tourism, A Destination Footprint and Scenario Tool PDFDocument22 pagesWhittlesea & Owen - Towards A Low Carbon Future - The Development and Application of REAP Tourism, A Destination Footprint and Scenario Tool PDFGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Lund, Benediktsson & Mustonen - The Eyjafjallajökul Eruption and Tourism - Report From A Survey in 2010Document30 pagesLund, Benediktsson & Mustonen - The Eyjafjallajökul Eruption and Tourism - Report From A Survey in 2010Gerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Robertson Roland - Globalisatio or GlocalisationDocument22 pagesRobertson Roland - Globalisatio or GlocalisationGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Conceptualizing Special Interest Tourism-Frameworks For AnalysisDocument18 pagesConceptualizing Special Interest Tourism-Frameworks For Analysissk8crew100% (2)

- Seeteram Neelu - A Dynamica Panel Data Analysis of The Immigration and Tourism Nexus PDFDocument27 pagesSeeteram Neelu - A Dynamica Panel Data Analysis of The Immigration and Tourism Nexus PDFGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Seeteram Neelu - A Dynamica Panel Data Analysis of The Immigration and Tourism Nexus PDFDocument27 pagesSeeteram Neelu - A Dynamica Panel Data Analysis of The Immigration and Tourism Nexus PDFGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Tosun Cevat - Expected Nature of Community Participation in Tourism Development PDFDocument12 pagesTosun Cevat - Expected Nature of Community Participation in Tourism Development PDFGerson Godoy Riquelme0% (1)

- Terhorst & Erkus-Öztürk - Scaling, Territoriality, and Networks of A Tourism Place PDFDocument17 pagesTerhorst & Erkus-Öztürk - Scaling, Territoriality, and Networks of A Tourism Place PDFGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality ResearchDocument23 pagesAnatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality ResearchGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation