Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

P H I L I P M - Stilvlson, N E W York, N. Y

Transféré par

Sandra SuryariniTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

P H I L I P M - Stilvlson, N E W York, N. Y

Transféré par

Sandra SuryariniDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SOME DEBATED POINTS IN THE TREATMENT OF ACUTE

POLIOMYELITIS

PHILIP M. STIlVlSON,

M.D.

NEW YORK, N. Y.

EFORE presenting some points in the treatment of acute poliomyelitis that

are frequent subjects of discussion, it is well to note that the Therapeutic

Trials Committee of the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry of the American

Medical Association has recently published an authorized report on "Methods

of Clinical Study and Evaluation of Therapeutic Agents in Poliomyelitis. ''1

This report showed that among the variables which must be controlled in

any investigation of the efficacy in this disease of a therapeutic agent or procedure, are the following:

Variations in diagnostic criteria

Unpredictability of the course of the disease

Unpredictability of the outcome

Effects of different immunologic types of the virus

Effects of climatic and geographic variations

Age distribution of patients

Variations in techniques of applying treatment

Variations in measuring and judging extent of paralysis, deformity, and

disability

Because of these many variables it is obviously necessary to have controlled

obse~wations of a very large number of patients to obtain an authentic evaluation

of the effect of a particular therapeutic procedure in poliomyelitis. This is

difficult to achieve and often impossible. However, able clinicians who have

observed hundreds, even thousands, of cases over the years develop impressions

of what is worth while and what is not; and at times equally experienced and

intelligent observers have come to opposing conclusions. While recognizing

that in many moot points what is right and best can be dete~nined only after

further research and study, one should find value, nevertheless, in stating some

of the pros and cons, particularly concerning treatment procedures. Up to

April 22, 1950, the United States has already had 1,449 cases spread across the

country, or 27 per cent more than at this time in 1949. It would seem well

therefore to discuss today those points which concern the practitioner, that he

may perhaps be helped in caring for his patients this year, rather than discussing points which involve equipment and laboratory facilities that are not

widely available.

First point: Shoutd all patients in early stages of the disease be transported to a hospital? The obvious advantages of a hospital are: better care for

the patient than can be given in most homes; more convenience for the doctor;

and the greater availability of laboratory studies and of special equipment

From the New York Hospital and the Department of Pediatrics, Cornell University

lVIedical College.

70~

STIMSON:

TREATMENT OF ACUTE POL:[OMYELITIS

705

should its need arise. On the other hand, Horstman, 2 in New Haven, and

Ritehie, a in England, have recently proved what had long been thought probable, that muscular exertion in the early febrile period aggravates the oncoming

paralysis. And in at least two hospitals this past summer a study of patients

in early stages of the disease transported great distances to the hospital cornpared with patients brought from the immediate neighborhood seemed to show

an average of greater severity in the former group.

Good clinical care can often be provided in even modest homes, particularly

since the best remedy at this time of fever is natural sleep. Unfortunately,

there are still many hospitals that admit polio cases--usually as private patients--that have a little equipment such as a ringer and a respirator, but very

little if any "know how," and where the patient is kept exhausted by overtreatment and unwise handling. During the febrile stage, the patient should

be furnished a maximum of rest, comfort, and relaxation. For no purpose

should he be awakened from natural sleep.

Should a lumbar puncture be done invariably? Before the onset of muscle

weakness, and with signs of meningeal irritation present, examination of the

spinal fluid is essential to rule out an early meningitis and perhaps to strengthen

the diagnosis of poliomyelitis. But when the presence of paralysis and of other

signs has made the clinical diagnosis obvious, the psychologic trauma and the

physical struggle incident to the puncture may very well be more harmful to the

patient's welfare than the information obtained is worth. Repeat lumbar punctures during the febrile period require a good bit of justifying.

Shall the patient be deliberately dehydrated, and if so, how? What are

some of the facts? At autopsy, when death has occurred in the first week and

even later, the weight of the brain is practically always appreciably greater

than the average for the age period, the increase being principally due to

cerebral edema, even though the eye grounds do not show choking of the discs.

Also in the cord, capillary circulation, and with it the blood supply of oxygen

to the anterior horn cells, is disturbed by peteehial hemorrhages and the choking

of perivascular infiltration and interstitial edema. Certainly, to quote Janeway, 4 dehydration (or something) is able to make dramatic clinical changes

in cases where there is intraeranial edema. In bu]bar cases, overhydration may

increase flooding of the pharynx, whereas dehydration helps to restrict the

amount of fluid that must be removed.

On the other hand, some believe that a state of "shock" with diminished

cardiac output is enough of a danger to warrant combatting dehydration; also,

that slow drip administration of 10 per cent glucose does not dehydrate.

Stronger glucose solutions do dehydrate but there may be a rebound. Some

prefer to use irradiated plasma, concentrated two and one-half times. Johnston, 4 at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, is convinced that dehydration is

beneficial, and Elam, ~ in Minneapolis, advises that the specific gravity of the

urine be kept between 1.025 and 1.030. Wright, 6 at Leetsda]e, Pa., routinely uses

10 per cent glucose for its apparently beneficial results and this was also our

routine procedure at the Knickerbocker Service in New York, where, it has

706

THE

JOURNAL

01~~ P E D I A T R I C S

been reported before, 7 of the last twenty-three bulbar cases we lost only one.

An additional patient, admitted at night in coma and dead in about three hours,

m a y also have been suffering from bulbar poliomyelitis. The attractive hypothesis, of course, is that these effects are produced by true dehydration although

the mechanism may be something else. Unless one makes elaborate studies of

blood volume, it would be hard to know if dehydration oeeurred.

As to medications for various purposes, there are of course many opinions

and many preferences, but there are also some facts. No antibiotic is known to

affect the poliomyelitis virus, but penicillin is given routinely by some authorities to prevent secondary infections as of the lungs. As to sedatives and analgesics, many believe these are necessary to combat the discomfort and pain so

common especiMly in the early days, and to p e r m i t the patient to get seine

sleep. Others recognize, however, that in a ease of polio that is progressing,

breathing difficulty may in a short time develop to proportions where conscious

effort is necessary to carry on the act of respiration. I f artificial sleep has been

induced, death may occur while the patient sleeps. In the acute, progressive

case, it is safest to forbid artificial sleep. Certainly, in each ease, the relative

advantages and disadvantages of such medication nmst be appreciated and

carefully evaluated.

~As to drugs intended to relieve muscle tightness and pain, Priscoline, a

sympatheticolytic drug, has been warmly advocated, but it has not been tried in an

adequately controlled study on alternate eases. Last summer at the Willard

P a r k e r Hospital it was given for a time to all patients in one ward and to none

in an adjacent ward, mild spinal eases being admitted alternately to the two

wards, and the house staff had the impression that if the drug was given in large

enough dosage to produce flushing of the skin, the patients did receive benefit

from it. I t has not had wide acceptance, nor has intravenous novaeaine, nor

curare, nor Prostigmine. Curare, which erects a barrier at the motor end

plates to certain of the stimuli coming from the brain, may have a field of usefulness for the patient who is struggling to breathe against a respirator by

knocking out the impulse to breathe. Prostigmine, which lowers the barrier

and is eurare's antidote, probably has its greatest usefulness in polio by stimulating intestinal peristalsis just before an enema. F o r the muscle twitches and

actual cramps that in occasional patients are a cause of considerable discomfort,

quinine is being used more and more commonly, and with usual benent.

F o r u r i n a r y retention there are sharp differences of opinion as to the use

of catheterization and the e a s y establishment of tidal drainage, or the use, as

recommended by Lawson, 8 of such a drug as f u r f u r y l t r i m e t h y l a m m o n i u m iodide

whieh is marketed u n d e r the name of Purmethide. In allergic patients this

drug can cause unpleasant side effects such as chilis, sweating, and even bronchospasm, and furthermore, in possibly a third of the eases, the usual dosage is

ineffective. Atropine, however, is a good antidote for the bronchospasm, and

Purmethide is often enough effective for u r i n a r y retention to w a r r a n t its use

STIMSON:

T R E A T M E N T OF ACUTE POLIOMYELITIS

707

when needed in selected nonallergie patients. An objection to the use of an

indwelling catheter is that it tends to prolong the period of urinary retention,

and the risk of eventual infection is therefore increased.

The use of postural drainage is the subject of much dispute. A much

quoted article s recently urged that the bed be tipped to 35 degrees to insure

drainage of the trachea, presupposing that bulbar patients are maintained in

a supine position as is usually done in a respirator. When the patient is in the

side-lying position usually used for bulbar cases out of a respirator, or is prone,

such an angle is not necessary, 20 degrees often being adequate. Some argue

that a continuous head-down position tends to cause edema of the head, both

inside and out, puffy eyelids, and increased choking of the discs having been

described. These doctors would have the patients horizontal from 10 to 50

minutes in each hour, but other clinicians believe that the advantages of a

moderate postural drainage, even continuous for several days, far outweigh

any POssible disadvantages.

There .is general agreement that oxygen should be given freely to patients

with bulbar involvements, as well as to those with any respiratory difficulty;

also .to those with apparent evidences of encephalitis because frequently the

trouble is not encephalitis but hypoxia. Most clinicians believe in giving the

oxygen by nasal instillation s o as to leave the mouth free for the removal of

secretions. It is not generally realized that if the oxygen is first passed through

hot water in order both to moisten and to warm the oxygen, it is less likely to

be irritating or to make the pharyngeal secretions stringy and inclined to cake.

Small injections of saline or of sodium bicarbonate solutions into the pharynx

or trachea during suction nlake possible a more rapid and easier removal of

sticky mucus.

There is some variance of opinion as to the relative merits and uses of tank

respirators, chest repirators, and the rocking bed, and in fact, as to when to

start any artificial respiration. When the tank respirators were the only avail

able means of mechanical artificial respiration, their obvious disadvantages

made some of us reluctant and slow to put patients in them unless the indications were pretty strong. Many a patient with minor breathing difficulty could

be carried along with oxygen and quiet and skillful nursing care until breathing

was again free from any distress. Today if a rocking bed is available, and if

the diaphragm is free from spasm and from encumbrance by abdominal distention, certain of these patients can well be carried along and rested by this

gentle form of artificial respiration. Where hypoxia is sufficient to cause

cyanosis, there is fairly general agreement that the tank respirator should be

used promptly. A climbing venous plasma carbon-dioxide combining power

above a normal of 62 volumes per cent is a good indication of a need for better

ventilation. A decrease in the p H of the urine is also significant.

The chest respirator is convenient for transportation and for emergencies,

but has definite disadvantages for prolonged use. The rocking bed is particularly useful for patients being weaned from tank respirators. Dr. Jessie

Wright 1~ of Leetsdale has probably had more experience with this type of arti-

708

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

fieial respiration than anyone, and has carefully defined the conditions and

regulations that should govern its use. For greatest advantage from this type

of artificial respiration, the chest and diaphragm must be pliable.

As to the use of differing pressures when the patient is in a tank respirator,

a number of suggestions have been advanced by various authorities. Under

most circumstances, a negative extrathoracie pressure of around 14 era. of

water is utilized, but most agree that the patient's maximum comfort should

be the goal and the pressure adjusted accordingly. Some would force deeper

breaths, perhaps for 5 minutes each hour, to keep the thoracic cage more flexible.

Many advocate intermittent positive pressure breathing applied by mask or

hood to t h e head or by special equipment to a tracheotomy tube, stating that

the advantages are the promotion of bronchial drainage, more uniform alveolar

aeration, protection against atelectasis, increase in lymph flow from the lungs,

and the combating of pulmonary edema.

When, in comparatively rare cases, the breathing difficulty is due to failure

of the respiratory center and a patient, usually semicomatose, breathes with

irregular and shallow breaths but can on demand take a good breath, Sarnoff's

electrophrenic respiration is apparently often effective in maintaining artificial

respiration by action on one-half of the diaphragm. All spontaneous effort at

respiration ceases with the onset of the phrenie nerve stimulation. But this

apparatus and the requisite skill of operation a r e pot yet widely available, and

opinions differ as to what can otherwise be done. Some give curare enough to

stop the motor impulses to the chest and let the tank respirator carry on. Some

whip up the respiratory center if necessary with caffeine and oxygen, but aim

to cut down the need for breathing by means of the utmost of quiet and rest.

As to the indications for traeheotomy, there are sharp differences of opinion.

At the Los Angeles County Hospital where 3,094 cases were treated in 1948, ~

a so-called prophylactic tracheotomy was performed in 354 or a majority of

their 603 bulbar and bulbospinal patients, both those eventually put in respirators and those not, and they reported a ]9.4 per cent mortality of their bulbar

and bulbospinal patients and an over-all mortality of 4.1 per cent. There are

many other clinicians, particularly West of the Mississippi, who favor early

tracheotomies, but most of the large clinics in the Eastern States use tracheotomies much more sparingly. For instance, the pooled figures of six hospitals 11

from Detroit to Boston show a total of 1,751 cases of polio admitted in 1949

with a mortality of only 3.2 per cent. Of these, 311 were bulbar and bulbar

spinal cases, with a mortality of 15.7 per cent in contrast to the 19.4 per cent

of Los Angeles. The six hospitals did only 19 tracheotomies of which 9 patients

died. Over one-tenth of all patients admitted with poliomyelitis had tracheotomies in Los Angeles, but only about one in 100 had traeheotomies in the

Eastern hospitals. Also, over one-half the bulbar patients in Los Angeles and

about 6 per cent in the Eastern hospitals had this operation done. Van Ripe~%~

the Medical Director of tbe National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, noted

in 1949, in his travels all over the United States, that there was generally a

markedly lessened tendency to do tracheotomies from what he had observed in

the preceding years.

STIMSON:

T R E A T M E N T OF ACUTE POLIOMYELITIS

709

The consensus of Eastern opinion might be summarized as follows :

I. Indications for Trc~cheotomy in Poliomyelitis

1. Bilateral abductor paralysis of the vocal cords. This causes a mechanical obstruction which must be by-passed.

2. Inability to kee/p the airway reasonably clear. Some clinics with good

teamwork can be notably more successful in this than others that are

overcrowded or have inadequate and untrained personnel.

3. Progressive hypoxia, not otherwise eorreetible.

II. A,dvantages of Tracheotomy

1. Easy removal of secretions from the trachea.

2. Ability to bronchoscope through the wound.

A n d if a p r o p e r oxygen a t t a c h m e n t is available, which usually i s n ' t :

3. Easier maintenance of adequate oxygen tension.

4. Easier treatment of pulmonary edema with positive pressure.

5. Easier to care for the patient.

III. Disadvantc~ges of Tracheotomy

1. The operation at best is an ordeal to the patient who needs rest and a

minimum of handling.

2. There are possible complications.

3. The mortality following tracheotomy in polio is high.

4, The tracheotomy tube narrows the airway and as a foreign body it

increases intratracheal secretions.

5. Tracheotomy makes adequate oxygen administration difficult unless a

proper oxygen attachment is available.

IV. Conditions Occasionally Cited as Indications for Tracheotomy, but Which

in Themselves Are Believed Insufficient Indications

1.

2.

3.

4.

Inability to cough.

Inability to swallow.

A n y laryngeal involvement besides bilateral abductor paralysis.

P u l m o n a r y edema. This requires positive pressure artificial respiration,

but besides through a traeheotomy tube, this can be given by mask, or

by a hood on a respirator.

5. Atelectasis. This, we believe, requires immediate suction which can be

better done visually by means of bronchoseopy than by blind suction

through a tracheotomy tube.

Thus, most Eastern clinicians who see much acute polio believe that tracheotomy

should be avoided if in any way possible.

A word might be added about the tilt4able which resembles a glorified

seesaw that can be secured at any desired angle from horizontal to 65 degrees,

head-up or head-down, with shoulder rests and foot rests. There is little if

any practical use for the head-down position, but raising a patient to put weight

on his feet who otherwise is too weak, too stiff, or too sore to assume other than

a straight-lying position, is thought by some to have several marked advantages.

The process of decalcification of the bones of the lower extremities may be

slowed; the kidneys empty better and there may be a lessened tendency to the

formation of renal calculi; a gradual adjustment of the patient's circulation to

the change from the horizontal to a more nearly upright position may be accomplished; and finally, the patient is immeasurably benefited psychologically.

It is believed that differences of opinion about the advantages of a tilt-table are

due only to lack of experience with its use.

710

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Finally, the older and more experienced the clinician, the greater and

more unanimous is the eonvietion that the welfare of the acutely ill polio patient

is best served by that expert medieal and nursing care which gives earnest consideration to attaining complete rest and comfort of the patient. In Cecil's

A Textbook of Medicine, 12 Paul has written, " I n thi~ particular disease one

should guard the patient from meddlesome therapy," and he advised against

" a n y procedures which will subjeet the patient to unneeessary strain." Thus,

unnecessary tests and examinations should be avoided. If it disturbs the patient,

the enthusiastic urge of the house-o~eer for study and researeh must be eurbed,

and thoughtful eonsideration of the patient should be substituted for the feeling

that "you've got to be doing something."

But no one can justifiably claim to say with authority what is best in the

treatment of acute polio. Such debatable points have been discussed as the

advisability of moving patients in early stages of the disease long distances,

o f using dehydration, and of prescribing various sedatives and antispasmodics;

the management of urinary retention; the use of the head-down position in

postural drainage; the warming of oxygen; the use of artificial respiration;

the pros and cons of tracheotomy; the advantages of the tilt-table; and the

importance of the fact that treatment that is not indicated is eontrMndieated.

Perhaps from the consideration of the pros and cons of these several points

there may result a better understanding of the management of the acutely ill

polio patient.

REFERENCES

1. J. A. IV[. A. 1~t0: 534, 1949.

2. Horstman, D. M.: Acute Poliomyelitis: Relation of Physical A c t i v i t y at the Time of

Onset to the Course of the Disease, J. A. ]Y[. A. 142: 236, 1950.

3. Ritehie, W. R.: P a r a l y t i c Poliomyelitis: E a r l y Symptoms a n d the Effects of PhysicM

A c t i v i t y on the Course of the Disease, Brit. iV[. J. 1: 465, 1949.

4. T h i r d Conference on Respiratory Problems in Polio, U n d e r the Auspices of the l~ational F o u n d a t i o n for I n f a n t i l e Paralysis, Boston, M a r c h 10-11, 1950.

5. Second Conference on Respiratory Problems in Polio, U n d e r the Auspices of the

N a t i o n a l F o u n d a t i o n for I n f a n t i l e Paralysis, Boston, June, 1949.

6. Personal communication.

7. Stimson, P. M.: The Diagnosis and T r e a t m e n t of B u l b a r Poliomyelitis, South. 1~. J.

42: 415, 1949.

8. Lawson, 1~. B.: The Use of F u r m e t h i d e for Paralysis of the Bladder From Poliomyelitis,

South. M. J. 41: 251, 1948.

9. Galloway, T. C., and Seifert, M. It.: B u l b a r Poliomyelitis, J. A. M. A. 141: 1, 1949.

10, Wright, Jessie: Mechanical Defects in the Rocking Bed W i t h Electronic Control and

Other Recommendations. ( P r i v a t e l y printed.)

11. H e r m a n K i e f e r Hospital, Detroit; H e n r y Ford Hospital, D e t r o i t ; Buffalo Children's

Hospital; ti:enny Clinic, Jersey City; Boston C h i l d r e n ' s Hospital; and the South

Department, Boston City Hospital.

12. Cecil, 1~. L.: A Textbook of Medicine, ed. 7, Philadelphia, 1947, W. B. Saunders

Company, p, 64.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults 10.1056@NEJMcp1816152Document8 pagesObstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults 10.1056@NEJMcp1816152Samuel Fraga SalvadorPas encore d'évaluation

- UW Qbank Step-3 MWDocument513 pagesUW Qbank Step-3 MWSukhdeep Singh86% (7)

- Tracheostomy Operating TechniqueDocument34 pagesTracheostomy Operating TechniqueIsa BasukiPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Treat: Septic ShockDocument6 pagesHow To Treat: Septic ShockmeeandsoePas encore d'évaluation

- Cancer of LarynxDocument46 pagesCancer of LarynxVIDYAPas encore d'évaluation

- Saranya .A: Contact DetailsDocument5 pagesSaranya .A: Contact DetailsCynosure- RahulPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Joseph's College of Quezon City Institute of NursingDocument19 pagesSt. Joseph's College of Quezon City Institute of NursingAdrian MangahasPas encore d'évaluation

- (Oxford Medical Histories) Schmidt, Dieter - Shorvon, Simon D - The End of Epilepsy - A History of The Modern Era of Epilepsy Research 1860-2010-Oxford University Press (2016)Document209 pages(Oxford Medical Histories) Schmidt, Dieter - Shorvon, Simon D - The End of Epilepsy - A History of The Modern Era of Epilepsy Research 1860-2010-Oxford University Press (2016)carlos fernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- NUR100 Sherpath Oxygenation and PerfusionDocument17 pagesNUR100 Sherpath Oxygenation and Perfusioncaloy2345caloyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bowel Obstruction Vs IleusDocument62 pagesBowel Obstruction Vs IleusSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- UMDNS CODES Concept DefinitionsDocument2 942 pagesUMDNS CODES Concept DefinitionsVictor Saldaña60% (5)

- Recent Advances in OtolaryngologyDocument305 pagesRecent Advances in OtolaryngologyDr. T. Balasubramanian80% (5)

- University of Northern PhilippinesDocument30 pagesUniversity of Northern PhilippinesClaudine JaramilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Care Plan For Appendicitis Post OperativeDocument17 pagesNursing Care Plan For Appendicitis Post OperativeOkaRizukiramanPas encore d'évaluation

- William Owens - The Ventilator Book (2018, First Draught Press)Document120 pagesWilliam Owens - The Ventilator Book (2018, First Draught Press)Ahad M AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- 3B Scientific Medical Education 2019 USDocument292 pages3B Scientific Medical Education 2019 USLeonardo JaimesPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study On Pneumonia (Real)Document28 pagesCase Study On Pneumonia (Real)Gleevyn Dela Torre86% (7)

- ENT Medicine and Surgery Illustrated PDFDocument298 pagesENT Medicine and Surgery Illustrated PDFahmed saadPas encore d'évaluation

- PneumothoraxDocument57 pagesPneumothoraxCamille Marquez100% (9)

- Difficult Airway 2011 Power Point PresentationDocument54 pagesDifficult Airway 2011 Power Point PresentationBalaji Mallela100% (1)

- Chapter - 030.bridge To NCLEX Review Question AnswersDocument7 pagesChapter - 030.bridge To NCLEX Review Question AnswersJackie JuddPas encore d'évaluation

- Dissertation On PneumoniaDocument7 pagesDissertation On PneumoniaCustomWrittenPaperLittleRock100% (1)

- Cesarean Section in Post-Polio PatientDocument2 pagesCesarean Section in Post-Polio PatientasclepiuspdfsPas encore d'évaluation

- General ObjectivesDocument28 pagesGeneral ObjectivesMei MeiPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review of PneumothoraxDocument4 pagesLiterature Review of Pneumothoraxc5e83cmh100% (1)

- PMLS 1 Module 2Document7 pagesPMLS 1 Module 2Jayson B. SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Value of The History of AnaesthesiaDocument5 pagesThe Value of The History of Anaesthesiamono011019Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pneumonia Thesis TopicsDocument8 pagesPneumonia Thesis Topicsdwt29yrp100% (2)

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughD'EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughSang Heon ChoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nac Leve Diseño de Estudios Cid 2008Document2 pagesNac Leve Diseño de Estudios Cid 2008Gustavo GomezPas encore d'évaluation

- Depression, Acceptance: Fundamentals of NursingDocument9 pagesDepression, Acceptance: Fundamentals of NursingTony GaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Asthma Dissertation IdeasDocument6 pagesAsthma Dissertation IdeasPaperWriterServiceSingapore100% (1)

- I. Readings Bronchopneumonia Bronchopneumonia Is An Illness of Lung Which Is Caused by Different Organism LikeDocument9 pagesI. Readings Bronchopneumonia Bronchopneumonia Is An Illness of Lung Which Is Caused by Different Organism Likeellis_NWU_09Pas encore d'évaluation

- I. Readings Bronchopneumonia Bronchopneumonia Is An Illness of Lung Which Is Caused by Different Organism LikeDocument9 pagesI. Readings Bronchopneumonia Bronchopneumonia Is An Illness of Lung Which Is Caused by Different Organism Likeellis_NWU_09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Allen College Homoeopathy Addressing Use of ProphylaxisDocument15 pagesAllen College Homoeopathy Addressing Use of ProphylaxisTarikPas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehensive Case Study On Pulmonary Embolism: Prepared byDocument17 pagesComprehensive Case Study On Pulmonary Embolism: Prepared byKristopher John JimenezPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study To Evaluate Effectiveness of Cold Application and Magnesium Sulphate Application On Superficial Thrombophlebitis Among Patients Receiving Intravenous Therapy in Selected Hospitals Amritsar.Document25 pagesA Study To Evaluate Effectiveness of Cold Application and Magnesium Sulphate Application On Superficial Thrombophlebitis Among Patients Receiving Intravenous Therapy in Selected Hospitals Amritsar.Navjot Brar71% (14)

- Jnma00736 0021Document3 pagesJnma00736 0021talenticaxo1Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2.11 SEPTIC ABORTION AND SEPTIC SHOCK. M. Botes PDFDocument4 pages2.11 SEPTIC ABORTION AND SEPTIC SHOCK. M. Botes PDFteteh_thikeuPas encore d'évaluation

- Eosinophilia and RashDocument3 pagesEosinophilia and RashmikelPas encore d'évaluation

- Seminar: Amy S Jordan, David G Mcsharry, Atul MalhotraDocument12 pagesSeminar: Amy S Jordan, David G Mcsharry, Atul MalhotraSerkan KüçüktürkPas encore d'évaluation

- Pneumonia: College of NursingDocument5 pagesPneumonia: College of NursingCharissa Magistrado De LeonPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Case Logs ReportDocument14 pagesClinical Case Logs ReportSeth Therizwhiz RockerfellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Chest Physical Therapy On Pediatrics Hospitalized With PneumoniaDocument9 pagesEffect of Chest Physical Therapy On Pediatrics Hospitalized With PneumoniaTri Anggeraini WulandariPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Pediatric Clinics - February2009Document291 pages01 Pediatric Clinics - February2009Tessa CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: Client Case Study 1Document14 pagesRunning Head: Client Case Study 1api-283774863Pas encore d'évaluation

- When Is It OK to Sedate a Child Who Just AteDocument7 pagesWhen Is It OK to Sedate a Child Who Just AteNADIA VICUÑAPas encore d'évaluation

- Pneumonia in Acute Stroke Patients Fed by Nasogastric Tube: PaperDocument5 pagesPneumonia in Acute Stroke Patients Fed by Nasogastric Tube: PaperLira PurnamawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chronic Cough Evaluation and Treatment GuideDocument13 pagesChronic Cough Evaluation and Treatment GuideRSU DUTA MULYAPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Topics in Pulmonary MedicineDocument4 pagesThesis Topics in Pulmonary Medicinegj6sr6d7100% (2)

- SOSD Phases of Fluid ResuscitationDocument8 pagesSOSD Phases of Fluid ResuscitationAvinash KumbharPas encore d'évaluation

- Internal Medicine Journal - 2016 - Beresford - Pyrexia of Unknown Origin Causes Investigation and ManagementDocument6 pagesInternal Medicine Journal - 2016 - Beresford - Pyrexia of Unknown Origin Causes Investigation and ManagementGoh Zheng YuenPas encore d'évaluation

- Non G.I. Causes of Chronic Diarrhoea: OP KapoorDocument6 pagesNon G.I. Causes of Chronic Diarrhoea: OP KapoorchandanPas encore d'évaluation

- PHD Thesis Samuel Coenen PDFDocument172 pagesPHD Thesis Samuel Coenen PDFsamuel_coenenPas encore d'évaluation

- Preoperative Fasting 2002Document7 pagesPreoperative Fasting 2002taupik rahmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Example Research Paper On LupusDocument8 pagesExample Research Paper On Lupuswhrkeculg100% (1)

- Reflections on Care of Young Polytrauma ICU PatientDocument7 pagesReflections on Care of Young Polytrauma ICU PatientAmanat KangPas encore d'évaluation

- Insult or Natural Process? Dehydration in The Terminally Ill - IatrogenicDocument6 pagesInsult or Natural Process? Dehydration in The Terminally Ill - Iatrogenicmariuz01Pas encore d'évaluation

- Asthma Thesis TopicsDocument5 pagesAsthma Thesis Topicsgjfcp5jb100% (1)

- NPT El FinalDocument40 pagesNPT El FinalSelma Alonso BuenabadPas encore d'évaluation

- MGX of SepticemiaDocument30 pagesMGX of SepticemiaAChRiS--FiTnEsSPas encore d'évaluation

- Unexpected Pulmonary Aspiration During Endoscopy Under Intravenous AnesthesiaDocument5 pagesUnexpected Pulmonary Aspiration During Endoscopy Under Intravenous AnesthesiaIta RositaPas encore d'évaluation

- Typhoid Fever: David T Wheeler, MDDocument14 pagesTyphoid Fever: David T Wheeler, MDChandra KushartantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal Reading ParuDocument53 pagesJournal Reading ParuDaniel IvanPas encore d'évaluation

- Eep Piilleep: A Revised Definition of EpilepsyDocument4 pagesEep Piilleep: A Revised Definition of EpilepsyNeuroAnatomiaInteractivaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chronic Cough Case Report: Chiari Malformation as an Unusual CauseDocument2 pagesChronic Cough Case Report: Chiari Malformation as an Unusual CauseVanetPas encore d'évaluation

- (Osborn) Chapter 47: Osborn, Et Al., Test Item File For Medical-Surgical Nursing: Preparation For PracticeDocument19 pages(Osborn) Chapter 47: Osborn, Et Al., Test Item File For Medical-Surgical Nursing: Preparation For PracticeKittiesPas encore d'évaluation

- A Novel Diagnostic Test For The Risk of AspirationDocument2 pagesA Novel Diagnostic Test For The Risk of Aspirationchrismerrynseka77Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ian's Update Newsletter: Ultrasound Procedures-Time To Start Respecting The Guide-Lines?Document10 pagesIan's Update Newsletter: Ultrasound Procedures-Time To Start Respecting The Guide-Lines?salsa0479Pas encore d'évaluation

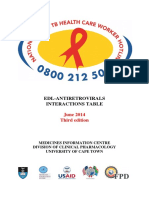

- Third Edition 2014 Full Booklet - 150212Document65 pagesThird Edition 2014 Full Booklet - 150212Sandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- Sclerostin Antibodies in Osteoporosis: Latest Evidence and Therapeutic PotentialDocument8 pagesSclerostin Antibodies in Osteoporosis: Latest Evidence and Therapeutic PotentialSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Psychiatric Impact of HIVDocument3 pagesThe Psychiatric Impact of HIVSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- Urinary Incontinence Jam A 2017Document13 pagesUrinary Incontinence Jam A 2017vennaPas encore d'évaluation

- Is AD A Stress-Related Disorder? Focus On The HPA Axis and Its Promising Therapeutic TargetsDocument9 pagesIs AD A Stress-Related Disorder? Focus On The HPA Axis and Its Promising Therapeutic TargetsSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- PTVH0247 Myki-Visitor-Pack Factsheet Attractions LR PDFDocument1 pagePTVH0247 Myki-Visitor-Pack Factsheet Attractions LR PDFsofi_8788Pas encore d'évaluation

- Prevalence of Hearing Impairment in Patients With Mild Cognitive ImpairmentDocument7 pagesPrevalence of Hearing Impairment in Patients With Mild Cognitive ImpairmentSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- Allostatic Load and Biological Anthropology: Ashley N. Edes Douglas E. CrewsDocument27 pagesAllostatic Load and Biological Anthropology: Ashley N. Edes Douglas E. CrewsSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- Dapus PaperDocument2 pagesDapus PaperSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- City Circle MapDocument1 pageCity Circle Mapjack.simpson.changPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal 1Document8 pagesJurnal 1Sandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- Dapus AaDocument2 pagesDapus AaSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- Contoh Surat SponsorgfcgDocument1 pageContoh Surat SponsorgfcgSandra SuryariniPas encore d'évaluation

- Tongue-Tied: Management in Pierre Robin Sequence: September 2017Document6 pagesTongue-Tied: Management in Pierre Robin Sequence: September 2017Mohamed AlaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Demonstration On Trechiostomy CareDocument10 pagesDemonstration On Trechiostomy Carejyoti singh100% (1)

- Sizing Chart PDFDocument3 pagesSizing Chart PDFCamilofonoPas encore d'évaluation

- CVP Insertion Close Tube Thoracostomy RDocument6 pagesCVP Insertion Close Tube Thoracostomy RFaye Nadine T. CABURALPas encore d'évaluation

- Tracheostomy Tube Reference GuideDocument17 pagesTracheostomy Tube Reference GuideTan Zhen YiPas encore d'évaluation

- TracheostomycaredraftDocument7 pagesTracheostomycaredraftAlane MorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Tracheostomy Management: 1. Overview and AnatomyDocument16 pagesTracheostomy Management: 1. Overview and AnatomymochkurniawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Paediatric Respiratory Reviews: Andreas P Eger, Ernst EberDocument9 pagesPaediatric Respiratory Reviews: Andreas P Eger, Ernst Eberadham bani younesPas encore d'évaluation

- Persistent Epiglottis FrenulumDocument16 pagesPersistent Epiglottis Frenulumandrea marigoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric and Adult Airway Management of AnesthesiaDocument141 pagesPediatric and Adult Airway Management of AnesthesiaMulatu MilkiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Artificial Airways for Mechanical VentilationDocument42 pagesArtificial Airways for Mechanical VentilationIssa MallariPas encore d'évaluation

- Open Access Atlas of Otolaryngology, Head & Neck Operative SurgeryDocument16 pagesOpen Access Atlas of Otolaryngology, Head & Neck Operative SurgeryMihai Ionut TanasePas encore d'évaluation

- MSN QUESTION BANK- POST OPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF MASTOIDITISDocument31 pagesMSN QUESTION BANK- POST OPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF MASTOIDITISkiran kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Artificial AirwayDocument3 pagesArtificial AirwayKusum RoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Tracheostomy Jurnal IDocument4 pagesTracheostomy Jurnal ILalu Reza AldiraPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 1097@CCM 0b013e31818b35f2Document7 pages10 1097@CCM 0b013e31818b35f2omarihuanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Tracheostomy CareDocument3 pagesTracheostomy CareKate Gabrielle Donal De GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- N Infection Control ManualDocument49 pagesN Infection Control ManualAnnu RajeshPas encore d'évaluation

- Anteriorregion (Robbinslevelvi-Inferiorpart) : CoremessagesDocument14 pagesAnteriorregion (Robbinslevelvi-Inferiorpart) : CoremessagesBarbero JuanPas encore d'évaluation

- E Learning NotesDocument260 pagesE Learning NotesGrape JuicePas encore d'évaluation

- Brachycephalic Airway DiseaseDocument10 pagesBrachycephalic Airway Diseaseludiegues752Pas encore d'évaluation