Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

2013 - A BJÖRKDAHL - Theinfluenceofstafftrainingontheviolenceprevention (Retrieved-2014!11!04)

Transféré par

fairwoodsTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

2013 - A BJÖRKDAHL - Theinfluenceofstafftrainingontheviolenceprevention (Retrieved-2014!11!04)

Transféré par

fairwoodsDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2013, 20, 396404

The influence of staff training on the violence

prevention and management climate in psychiatric

inpatient units

jpm_1930

396..404

A. BJRKDAHL1 phd rmn, G. HANSEBO3 rnt phd &

T. P A L M S T I E R N A 2 p h d m d

1

Senior Nurse Consultant, Division of Psychiatry, 2Assistant Professor, Social and Forensic Psychiatry Program,

Division of Psychiatry, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, and 3Head of department of

Health Caring Sciences, Ersta Skndal University College, Stockholm, Sweden

Keywords: inpatient, management, pre-

Accessible summary

vention, staff training, violence, ward

climate

Correspondence:

A. Bjrkdahl

SLSO

Box 179 14

SE-118 95 Stockholm

Sweden

E-mail: anna.bjorkdahl@sll.se

Accepted for publication: 13 April 2012

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01930.x

Violence prevention and management is an important part of inpatient psychiatric

nursing because both patients and staff need to feel safe and secure.

The Bergen model is a violence prevention and management staff-training programme that is based on the three essential staff factors of the City model: positive

appreciation of patients, emotional regulation and effective structure.

Based on the City model, we developed a 13-item questionnaire in order to find out

how patients and staff rated the violence prevention and management climate on

psychiatric wards where the staff was trained according to the Bergen model

compared with wards where the staff was not trained.

The result showed that the staff on trained wards had a more positive perception of

the violence prevention and management climate on four of the items and the

patients on one item.

Abstract

Violence prevention and management is an important part of inpatient psychiatric

nursing and specific staff training is regarded essential. The training should be based on

primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. In Stockholm, Sweden, the Bergen model

is a staff-training programme that combines this preventive approach with the theoretical nursing framework of the City model that includes three staff factors: positive

appreciation of patients, emotional regulation and effective structure. We evaluated

this combination of the Bergen and City models on the violence prevention and

management climate in psychiatric inpatient wards. A 13-item questionnaire was

developed and distributed to patients and staff in 41 wards before the staff was trained

and subsequently to 19 of these wards after training. Data analyses included factor

analysis, Fishers exact test and MannWhitney U-test. The result showed that the staff

on trained wards had a more positive perception of four of the items and the patients

of one item. These items reflected causes of patient aggression, ward rules, the staffs

emotional regulation and early interventions. The findings suggest that a focus on three

levels of prevention within a theoretical nursing framework may promote a more

positive violence prevention and management climate on wards.

396

2012 Blackwell Publishing

Violence prevention and management staff training

Introduction

Patient aggression and violent behaviour are well-known

phenomena within psychiatric inpatient wards. Many

studies have described its negative influence on the experience of safety and security for both patients and staff: the

risk of physical and psychological injury and the use of

restraint, seclusion and forced medication (Olofsson &

Jacobsson 2001, Bowers et al. 2006b, Richter & Whittington 2006, Jarrett et al. 2008, Stubbs et al. 2009). In the

present study, we therefore wanted to explore how a violence prevention and management programme used in

Sweden may have influenced the ward climate in psychiatric inpatient units.

Background

Violence prevention and management is considered to be

an important as well as challenging part of inpatient psychiatric nursing and specific staff training is regarded as

essential (International Labor Office et al. 2002, Farrell &

Cubit 2005, Beech & Leather 2006). The various theories

concerning causes for inpatient aggression and violence are

often grouped into three explanatory models: the internal,

the external and the situational/interactional model

(Nijman et al. 1999, Duxbury & Whittington 2005). Traditionally, many violence prevention and management

training programmes for staff have relied mostly on the

internal patient explanatory model to violence (Paterson

et al. 2010). By assuming that the major cause of patient

violence is related to symptoms of mental illness and other

individual patient characteristics, a reactive and controlling

approach to aggression and violence has often been

applied. As a consequence, the training has been focused on

self-defence as well as various control and restraint techniques (Duxbury 2002, Farrell & Cubit 2005, Beech &

Leather 2006, Paterson et al. 2010). However, during the

last two decades, an increasing amount of research has

supported the view that violent patient behaviour is often a

result of a complex interplay of different internal, external

and situational/interactional factors (Richter & Whittington 2006). The current international recommendations

regarding violence prevention and management training of

staff in health-care settings therefore state that this complexity must be taken into account and that a proactive

rather than reactive approach should dominate the training

(Krug et al. 2002, Council of Europe 2004, International

Council of Nurses et al. 2005). Moreover, it should be

based on preventive principles of public health including

three dimensions of prevention: primary, secondary and

tertiary prevention (International Labor Office et al. 2002,

Krug et al. 2002). In psychiatric inpatient care, the aim of

2012 Blackwell Publishing

the level of primary prevention is to create an everyday

climate on the wards that minimizes the risk for violence

to develop. This includes, for example, good staffpatient

relationships, risk assessment, the use of care plans and an

adjusted physical ward milieu. Secondary prevention is

used when violence is perceived as imminent and often

comprises the use of de-escalation techniques. On the tertiary level a violent situation is already present and prevention may include taking safe physical control of a patient

as well as performing a post incident analysis (Delaney

& Johnson 2006, Paterson et al. 2009). The approach

requires action at the level of organization and management, the staff team, the individual staff member and the

individual patient (Paterson et al. 2005).

In order to establish the effects of various types of violence prevention and management staff training it is important that the programmes are systematically evaluated

(Johnson 2010). However, in two major review studies

of the effects of staff training, Richter et al. (2006) and

Johnson (2010) found that the varying quality and heterogeneity of the studies included in the reviews and the

numerous ways of defining and registering incidents made

evaluation of the effects difficult and that there was no clear

proof of a reduction of incidents as a result of staff training

(Richter et al. 2006). The most common outcome measurements were aggression incident rates and rates of coercive

measures. Several studies also included staff confidence in

dealing with aggression as well as changes in attitudes and

knowledge. Only one study included evaluation ratings

made by patients. This indicates that although the reduction of incident rates is an important outcome variable,

there is also a need for further evaluation focusing on

preventive variables that address the central parts of the

recommended proactive public health approach. Furthermore, qualitative variables such as ward climate and the

perspectives of both patients and staff may add further

depth and knowledge to a more comprehensive evaluation

process (Steinert 2002, Abderhalden 2008).

The aim of this study was to explore the influence of a

violence prevention and management staff-training programme, the Bergen model, used in Sweden, on the violence prevention and management climate in psychiatric

inpatient wards. For the purpose of this study, we coined

the term violence prevention and management climate

based on the previously described public health approach

to violence prevention and the theoretical nursing-based

framework of the City model (Bowers 2002). We defined

the term as within the dimensions of primary, secondary

and tertiary violence prevention, referring to the subjective perception of the staff and patients regarding staff

members positive appreciation of patients, their selfregulation of emotional responses and the efficacy of the

397

A. Bjrkdahl et al.

structure surrounding rules and routines, including the

general perception of safety and security on the ward.

Methods

We conducted a prospective non-randomized intervention

study with beforeafter intervention comparisons using an

independent measures design. The local research ethics

committee approved of the study. The study was conducted

in Stockholm, Sweden. In Sweden, employees working in

places where aggression and violence may be expected have

a legislated right to appropriate training provided by their

employer (Swedish Work Environment Authority 1993).

Within Swedish psychiatry, the arrangements have usually

been a matter for the local psychiatric clinics. Training

seems to have been provided by various sources such as

private training companies, self-defence or martial arts

sports clubs or by individual dedicated members of staff.

No common format for this type of staff training appears

to exist on the national level and the extent, content and

quality of such training programmes in Sweden has rarely

been systematically evaluated.

Intervention

The Bergen model is a non-commercial violence prevention

and management training programme for psychiatric inpatient staff. It originates from the Norwegian TERMA

training model that has been developed at the Haukeland

University Hospital, Department of Forensic Psychiatry in

Bergen. In Sweden, the TERMA model was first introduced at the psychiatric department of the Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge in Stockholm. There, it was

subsequently adjusted to fit into Swedish general psychiatry

and renamed the Bergen model. In addition, the Bergen

model was adjusted to clarify a theoretical nursing framework, inspired by the public health approach (International

Labor Office et al. 2002) and strongly influenced by the

City model (Bowers 2002). The City model is a theoretical nursing-based framework that describes three staff

factors that are considered vital to reducing conflicts and

containment in psychiatric wards. These are: (i) positive

appreciation of patients, which refers to a psychiatric philosophy that promotes a psychological understanding of

difficult patient behaviour and a moral commitment to

values such as humanism and non-judgementalism; (ii) selfregulation of emotional responses, which includes awareness and control of feelings, especially fear and anger;

and (iii) effective structure of rules and routines, which

addresses teamwork skills, organizational support, clarity

of ward rules, early recognition of the interventions needed

and an organized manner in handling challenging situa398

tions. The City model has been used to guide several

intervention studies on psychiatric wards to study the

effects on aggression and violence (Bowers et al. 2006a,

2008, Bowers 2009).

The Bergen model puts forward primary prevention

factors based on good staffpatient relationships. The participants are encouraged to reflect on their own apparent

or unspoken approach to patients and patient aggression,

as well as the culture and organization of wards. The

training also includes aggression theory, ethics in care,

ward rules and routines, risk factors and risk assessment,

laws and legislations and the impact of the physical

environment. The secondary and tertiary sections of the

training address limit-setting styles and negotiation, selfdefence, physical restraint techniques (so-called pain compliance techniques are not used) and safety issues, the use

of mechanical restraint, seclusion and forced medication,

post-incident sessions with the patient and with the staff

and critical reviewing of violent incidents. If possible, participants are encouraged to allow conflict situations to

take time, to try to understand the background of the

situation and find a solution that is acceptable for everyone involved. Co-operation among all staff members and

between staff and patient is considered vital to the model.

The three staff factors of the City model work as guiding

principals on the primary, secondary and tertiary levels of

prevention of the training. The programme comprises a

4-day course for staff of all professions on psychiatric

wards, equally distributed between theoretically oriented

and practical sessions. Trainers are recruited and handpicked from clinically active staff within the clinic, and

trained in a special training trainers course (approximately 70 h) by Bergen model representatives. Following

the 4-day course, refresher classes are arranged and

offered regularly within the local clinics to all staff

members at least once every 6 months. The refresher

classes are based on the participants current experiences

with patients and colleagues and refer to both theory and

practice. The Bergen model has not been previously

subject to any systematic evaluation and the intervention

of this study could be described as a combination of the

Bergen and City models.

In 2006, the Stockholm County Council in Sweden

decided to start using the Bergen model in the violence

prevention and management staff training of the inpatient

psychiatric units within the organization. A senior manager

(the first author A.B.) with overall responsibility for the

introduction as well as the evaluation of the programme

was appointed by the central organization. The risk of bias

in the evaluation process was recognized and addressed by

involving co-researchers and by using theoretically derived

frameworks for the development of an evaluation question 2012 Blackwell Publishing

Violence prevention and management staff training

naire. The sample in this study comprised of patients and

staff on all of the 41 wards on the eight hospitals that

would undergo staff training according to the Bergen

model. The 41 wards were emergency and admission wards

(n = 2), general wards including wards for psychotic and

affective disorders (n = 30), psychiatric intensive care units

(n = 2), drug and alcohol dependence wards (n = 2) and

forensic wards (n = 5). Most wards consisted of 1218 beds

with 3035 nursing staff members along with a team of

multidisciplinary professions. The two emergency and

admission wards had each more than 50 employees. Prior

to the introduction of the Bergen model, the wards within

the organization were with few exceptions not involved in

any structured or regular staff training in violence prevention and management. Most new employees would,

however, in the beginning of their employment, participate

in a few days of self-defence training provided by a local

sports club.

Outcome measure

In order to evaluate the intervention, we sought a questionnaire that could be used for both patients and staff and that

adhered to the following premises: (i) each item would

relate to one or more of the three City model staff factors;

(ii) each item would be congruent to the content of the

Bergen model training programme and to the public health

approach; (iii) items should be observable by both staff and

patients; (iv) the number of items should be restricted,

making the questionnaire short and easy to use; and (v) the

items should be relevant to any type of psychiatric inpatient

ward. No such questionnaire was found in the literature.

We therefore formulated a number of questionnaire statements that were judged as specifically addressing all of

the stated premises and subsequently reduced them to a

13-item questionnaire. Of the 13 items, three were formulated as negative statements (item 4, 8 and 12) (DeVellis

2003). We called the questionnaire E13 (E being the first

letter in the Swedish word for questionnaire). For the

purpose of this paper, two professional translators conducted a translationcounter-translation process of the E13

from Swedish to English. The E13 was designed to collect

dichotomous data that would reflect the participants basic

agreement or disagreement to each of the questionnaire

statements. However, because participants may find it difficult to choose from only two response options, four levels

of agreement to the statements were included, from (1) not

at all, (2) unspecified, (3) unspecified, to (4) totally (Rossberg & Friis 2003). A fifth option, do not know, was also

available. Descriptive data included in the questionnaire

were for staff: sex, age category and occupation, and for

patients: sex and age category.

2012 Blackwell Publishing

Data collection

The data collection commenced in 2007. The E13 was

sent out to all participating wards (n = 41) 3 months

before the first wards were scheduled to start the training.

A research assistant was appointed on each participating

clinic to give information about the study and to distribute and collect questionnaires. The E13 was distributed to

all employed staff and to all patients that the staff assessed

as meeting the inclusion criteria. The criteria included the

ability to read and speak Swedish and the ability to understand the meaning of informed consent. Furthermore,

with respect to the mental and physical health of the

patient, the psychiatrist in charge was able to disapprove

of a patients participation. If possible, the E13 questionnaire was offered to the patients near discharge. An

enclosed letter described the purpose of the study and the

voluntary and anonymous nature of participation. No

coding or any other possibilities of identifying individual

patient or staff participants were made. Together with the

questionnaire, each participant received an unmarked

sealable envelope. A sealed box for collecting the questionnaires was placed on each ward. The data collection

continued for 1 month on each ward. Three to 6 months

after a ward had been trained, the same E13 questionnaire

was sent out again following the same procedures. In

December 2008, the data collection terminated. By then,

19 wards on six hospitals had finished their training and

completed the second round of the questionnaire (one

emergency and admission ward, 13 general wards, two

psychiatric intensive care units and three forensic wards).

Patient and staff turnover and the anonymity of the participants before and after the intervention meant that

the data were collected from independent samples. The

number of distributed questionnaires was not specifically

counted and response and exclusion rates were therefore

not known.

Data analysis

In order to analyse the interrelationship among the questionnaire items a factor analysis was performed, using

an exploratory principal component analysis including

varimax rotation and allowing for factors with an eigenvalue of >1.0 to emerge. In this analysis a three-factor

solution appeared. However, the three factors appeared

weak with a substantial cross-loading of >0.25 between

all factors on several items (Raubenheimer 2004). Furthermore, the second and third factor showed unsatisfactory internal consistency, Cronbachs a < 0.65 (Table 1).

Therefore we assumed that the 13 items may be viewed as

399

A. Bjrkdahl et al.

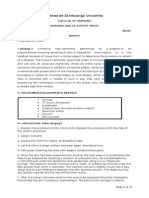

Table 1

Summary of exploratory principal component analysis for the E13 questionnaire

Rotated factor loadings

Item

7. Being on the ward feels safe and secure

5. The staff manage to calm aggressive patients down

6. The rules for patients on the ward are good

11. The staff approach patients already at the first signs of aggression

3. The staff co-operate when approaching aggressive patients

9. The staff are calm when approaching aggressive patients

1. The staff are often out on the ward with patients

10. The staff try to understand why a patient is acting aggressively

2. The relationship between staff and patients is good

13. Both female and male staff are involved in approaching aggressive patients

12. The staff are harsh with aggressive patients

8. Only certain members of staff are capable of approaching aggressive patients

4. Patients are often scared of other patients

Eigenvalues

% of variance

Cronbachs a

0.717

0.692

0.680

0.614

0.579

0.527

0.091

0.370

0.282

0.282

-0.069

0.224

0.404

4.558

35.2

0.729

0.092

0.232

0.064

0.408

0.427

0.478

0.736

0.560

0.525

0.407

0.294

0.184

-0.441

1.193

9.17

0.624

0.136

-0.007

0.170

0.148

0.093

0.182

0.047

0.292

0.197

0.264

0.721

0.649

0.557

1.027

7.90

0.400

The table shows the three-factor solution that was rejected in favour of a one-dimensional solution (Cronbachs a = 0.828).

measuring one dimension with no further meaningful

underlying components. This assumption was further

strengthened as the one-factor solution showed a satisfactory internal consistency, Cronbachs a = 0.83. As the

next step, the differences between the trained and the

untrained wards responses to each separate questionnaire

statement were calculated, using Fishers exact test.

Because data were collected on an independent, categorical level from different samples before and after the intervention, a dichotomization was made, which meant that

the nuances of the four levels of the response options

would not be considered in the analysis (DeVellis 2003).

This was made by sorting agreement options one and two

as a disagreement (no) and options three and four as an

agreement (yes). All questionnaires that included any of

the four agreement options for the particular item were

considered valid, excluding the response option do not

know. The data were calculated separately for patients

and staff. In order to further measure the impact of the

intervention, the effect size was calculated using odds

ratio (Field 2009). Finally, the difference between trained

and untrained wards was calculated for the questionnaire

as a whole. A sum score model was used based on the

dichotomized data. The model gave value 1 to statement

options three and four on all items except for the three

negative items (item 4, 8 and 12) where the value 1

was given to the statement options one or two. All other

options were given the value 0. Thus, a sum score range

for each questionnaire of 013 was obtained. The differences were analysed using MannWhitney U-test. All

questionnaires that included any of the four agreement

options on all 13 items were considered valid. P-values

of 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were

400

performed using the spss software (version 16.0, IBM,

Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Staff

A total of 854 staff questionnaires were collected from 41

wards before the training started and 260 staff questionnaires were subsequently collected from the 19 wards that

had been trained. Descriptive data for staff and patients are

presented in Table 2. In the analysis of the differences in the

total questionnaire sum scores, the perception was significantly more positive among staff on the trained wards as

compared with the wards that had yet not been trained,

MannWhitney P = 0.045. The results of the separate item

analysis showed that staff working on wards that had been

trained according to the Bergen model differed significantly

in their perception of violence prevention and management

climate regarding four of the 13 statements compared with

staff working on wards that had not yet been trained

(Table 3). The differences all corresponded to a more positive perception on the trained wards. The areas that were

perceived significantly more positive concerned ward rules

(statement 6), the emotional regulation of staff members in

challenging situations (statement 9), the staffs interest in

possible causes for patient aggression (statement 10) and

the staffs readiness to intervene at an early stage of patient

aggression (statement 11). In addition, just above the level

of significance was statement 2 concerning good relationships between patients and staff (P = 0.06) and statement

3 that related to the staffs ability to co-operate when

approaching aggressive patients (P = 0.058).

2012 Blackwell Publishing

Violence prevention and management staff training

Table 2

Descriptive data of staff and patients

Staff

Wards (n)

Total responses (n)

Responses/ward (n) (mean, range)

Female/male (%)

Age (%)

25

2640

>40

Occupation (%)

Nursing assistant

Registered nurse

Physician

Paramedic

Other

Patients

Before training

After training

Before training

After training

41

854

21 (256)

60/40

19

260

14 (419)

58/42

41

297

8 (118)

45/55

19

156

8 (120)

49/51

4

31

65

2

30

68

63

28

4

2

3

67

28

2

1

2

14

34

52

12

26

62

Table 3

E13 scale content: staff ratings before and after training, Fishers exact test P-value

Item

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

The staff are often out on the ward with patients

The relationship between staff and patients is good

The staff co-operate when approaching aggressive patients

Patients are often scared of other patients

The staff manage to calm aggressive patients down

The rules for patients on the ward are good

Being on the ward feels safe and secure

Only certain members of staff are capable of approaching

aggressive patients

The staff are calm when approaching aggressive patients

The staff try to understand why a patient is acting aggressively

The staff approach patients already at the first signs of

aggression

The staff are harsh with aggressive patients

Both female and male staff are involved in approaching

aggressive patients

Before training % (n)

After training % (n)

Agree

Disagree

Agree

Disagree

Effect size

(odds ratio)

88.4

94.6

91.3

42.8

91.8

76.9

87.4

65.5

11.6

5.4

8.7

57.2

8.2

21.9

12.6

34.5

89.6

97.6

95.0

39.0

94.6

87.3

91.0

68.9

10.4

2.4

5.0

61.0

5.4

12.7

9.0

31.1

0.729

0.060

0.058

0.332

0.169

0.001*

0.144

0.348

1.12

2.31

1.85

0.86

1.56

1.97

1.45

1.17

(750)

(800)

(772)

(350)

(779)

(655)

(746)

(538)

(98)

(46)

(74)

(468)

(70)

(187)

(108)

(284)

(215)

(241)

(231)

(93)

(226)

(214)

(221)

(162)

(25)

(6)

(12)

(145)

(13)

(31)

(22)

(73)

88.6 (749)

83.8 (707)

80.3 (653)

11.4 (96)

16.2 (137)

19.7 (160)

94.5 (227)

89.4 (211)

89.5 (214)

5.5 (13)

10.6 (25)

10.5 (25)

0.007*

0.031*

0.001*

2.24

1.64

2.10

24.7 (201)

85.3 (719)

75.3 (612)

14.7 (124)

20.6 (49)

87.8 (208)

79.4 (189)

12.2 (29)

0.195

0.399

0.79

1.24

*P < 0.05.

Patients

Discussion

In the analysis of the differences in the total scores of

the patient questionnaire, no significant improvement was

found on the trained wards as compared with the untrained

wards, MannWhitney P = 0.471. The separate item analysis showed that patients staying on trained wards (n = 156)

differed significantly in their perception of violence prevention and management climate on one of the 13 statements

compared with patients staying on wards that had yet not

received training (n = 297) (Table 4). On the trained wards,

patients rated more positive perceptions of the staffs interest in finding possible causes for patient aggression (statement 10). There was also an almost significant difference

(P = 0.09) concerning a more positive perception of the

emotional regulation of the staff in challenging situations

(statement 9). No statement was rated significantly more

negative on the trained wards.

The City model (Bowers 2002) is an important and influential theoretical nursing framework of the Bergen model.

Thus, the Bergen model may serve as one example of how

the results of Bowers and colleagues intensive and longterm psychiatric nursing research on violence prevention

and management is used and implemented in clinical practice in Sweden. By using the City model as the foundation

of the construction of the E13, we believe that this questionnaire may be useful to evaluate the City model within

clinical practice in general and not only in the context of

the Bergen model.

The one statement that was more positively perceived by

the patients on trained wards as well as by the staff was

statement 10: The staff try to understand why a patient is

acting aggressively. Interestingly, this item reflects some

fundamental aspects of nursing, such as relating to and

2012 Blackwell Publishing

401

A. Bjrkdahl et al.

Table 4

E13 scale content: patient ratings before and after training, Fishers exact test P-value

Item

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

The staff are often out on the ward with patients

The relationship between staff and patients is good

The staff co-operate when approaching aggressive patients

Patients are often scared of other patients

The staff manage to calm aggressive patients down

The rules for patients on the ward are good

Being on the ward feels safe and secure

Only certain members of staff are capable of approaching

aggressive patients

The staff are calm when approaching aggressive patients

The staff try to understand why a patient is acting aggressively

The staff approach patients already at the first signs of

aggression

The staff are harsh with aggressive patients

Both female and male staff are involved in approaching

aggressive patients

Before training % (n)

After training % (n)

Agree

Disagree

Agree

Disagree

Effect size

(odds ratio)

83.8

83.6

86.8

31.8

79.4

75.3

84.0

61.5

16.2

16.4

13.2

68.2

20.6

24.7

16.0

38.5

87.2

86.4

88.6

35.2

81.3

72.0

85.6

64.2

12.8

13.6

11.4

64.8

18.7

28.0

14.1

35.8

0.400

0.487

0.731

0.556

0.686

0.484

0.681

0.706

1.32

1.24

1.19

1.17

1.13

0.84

1.16

1.12

(249)

(245)

(177)

(78)

(185)

(217)

(247)

(112)

(48)

(48)

(27)

(167)

(48)

(71)

(47)

(70)

(130)

(127)

(109)

(43)

(109)

(103)

(134)

(68)

(19)

(20)

(14)

(79)

(25)

(40)

(22)

(38)

78.8 (175)

70.5 (146)

71.5 (138)

21.2 (47)

29.5 (61)

28.5 (55)

86.2 (119)

82.6 (95)

76.1 (89)

13.8 (19)

17.4 (20)

23.9 (28)

0.093

0.022*

0.428

1.68

1.98

1.27

38.6 (76)

86.4 (178)

61.4 (121)

13.6 (28)

35.3 (41)

88.0 (110)

64.7 (75)

12.0 (15)

0.629

0.738

0.87

1.15

*P < 0.05.

communicating with the patient as an individual (Peplau

1997, Delaney & Johnson 2006). Furthermore, this result

may demonstrate an increased openness and interest

among staff in more complex ways of viewing possible

causes of patient aggression (Duxbury 2002, Duxbury &

Whittington 2005). Because the statement 10 pictures an

already aggressive patient, it represents the secondary and

tertiary levels of prevention. By trying to understand the

patients reasons for behaving aggressively, the staff not

only has a better chance of finding a way to solve the

problem, but may also build a more trustful relationship

with the patient.

It is promising to find that the four more positively

perceived statements put together (statements 6, 9, 10 and

11) includes all three staff factors in the City model: staffs

positive appreciation of patients, emotional regulation and

effective structure (Bowers 2002). Moreover, the four statements also cover the three levels of the public health

approach to violence prevention (International Labor

Office et al. 2002). This suggests that the intention of the

Bergen model training programme to be based on the two

theoretical frameworks is realized in the staff training in a

way that makes it possible for the participants to put it into

nursing practice. Furthermore, it indicates that the E13

scale appears to have the capability to detect differences

within all the different aspects of the two theoretical

frameworks.

A proactive approach to patient aggression and violence

requires nurses to take an active and health-promoting role

towards the patients and in working together with the

multidisciplinary team. This is opposed to a more passive

or reactive role that involves waiting for signs of aggression

to appear and for other members of the ward team to make

the decisions regarding what actions is to be undertaken. In

402

an interview study, Bjrkdahl et al. (2010) suggested that

the caring approaches of nursing staff in acute psychiatry

appeared to vary between the different approaches of the

bulldozer and the ballet dancer, reflecting a range of

controlling and caring interventions. The authors found a

risk of the control-oriented bulldozer approach to become

uncaring and harmful to the nursepatient relationship. At

the same time, the nurses in the study described how the

bulldozer approach often involved high emotional strain

and a continuous inner dialogue on present ethical dilemmas. Similarly, when studying nurses limit-setting interventions on an acute psychiatric ward, Vatne & Fagermoen

(2007) found two simultaneous and conflicting perspectives: to correct and to acknowledge. The two perspectives reflected both a one-sided asymmetric nursepatient

relationship that the nurses felt often conflicted with their

ideals, which were geared towards understanding, valuing

and confirming the patient. The result of our present study

indicates that the combination of the public health perspective on violence prevention and the theoretical framework

of the City model in staff training may be a step forward

in the development of violence prevention and management interventions that are perceived by patients as not

only controlling but also caring. It is also possible that the

moral stress that nurses often experience in challenging

situations (Lutzen et al. 2010) would vane when substantial caring and preventive aspects become regularly and

consciously utilized components of the nurses approach

even on the levels of secondary and tertiary prevention.

Similar to the studies by Bowers and colleagues (Bowers

et al. 2006a, 2008, Brennan et al. 2006, Flood et al. 2006)

our study includes the theoretical framework of the City

model (Bowers 2002). When testing the theorys influence

on rates of conflict and containment on 136 acute psychi 2012 Blackwell Publishing

Violence prevention and management staff training

atric wards, it was found that the most important of the

three staff factors of the model, was related to effective

structure (Bowers 2009). Interestingly in our study, the one

item that was rated significantly higher by both patients

and staff on trained wards was related to the staff factor of

positive appreciation of patients (statement 10: The staff

try to understand why a patient is acting aggressively).

This may indicate that the staff factor of effective structure

could be of high relevance to the incident rates of patient

aggression and violence while the staff factor of positive

appreciation of patients may be more directed at evaluation

variables of a qualitative character such as the ward

climate. In another study, Hahn et al. (2006) used the

Management of Aggression and Violence Attitude Scale

(Duxbury 2003) to evaluate the effects of an aggression

management course on the attitudes of staff. No significant

difference was found after the training and the authors

suggested that beside attitudes, it may be important to also

evaluate the effect of training on affective components of

staff or practical handling skills (Hahn et al. 2006). This

shows that the E13 scale may prove useful because it

includes both affective and practically oriented statements

and also appears to be capable of detecting changes in

those components following staff training.

Methodological considerations

The methodological strength of this study includes the

participation of patients. The importance of including the

opinions of patients in the evaluation of effects of violence

prevention and management staff training has been emphasized in previous research (National Institute for Clinical

Excellence 2006). Nonetheless, literature reviews show that

this is still uncommon (Richter et al. 2006, Johnson 2010).

However, the result of this study should be interpreted with

caution and there are several methodological issues to be

addressed. The lack of control groups is a limitation of the

study design, which gives rise to uncertainty regarding to

what extent the observed changes were due to the staff

training or other confounding variables (Johnson 2010). It

should also be noted that the E13 scale was developed

without having the item pool reviewed by experts or prior

testing of the items on a development sample. Because the

psychometric testing was made directly on the research

sample, the robustness of the E13 scale should be further

established by a repeated factor analysis the next time the

scale is used. The interpretation of a factor analysis ultimately comes down to a subjective evaluation of what

solution appears to be the most meaningful in the light of

theory (DeVellis 2003). Our interpretation was in favour of

the E13 being a one-dimensional scale. In further testing,

this interpretation may be supported or challenged.

2012 Blackwell Publishing

Four of the items were significantly improved in the staff

ratings on trained wards compared with one item in the

patients ratings. This could indicate that the Bergen model

influences violence prevention and management climate

more positively for the staff than for the patients. At the

same time, it is likely that many of the staff members worked

on the same wards during the whole research period while

there was a constant flow of admittances and discharges of

patients. The improved staff ratings could, therefore, to a

higher degree than for the patients, reflect a comparison

between the wards violence prevention and management

climate before and after training. To implement sustainable

change in working culture takes time and it is possible that

the duration of the study was too short and that a third data

collection could have added further information on the

influence of the intervention. One strength of this study is

that the samples were relatively large. In future research, it

would however be valuable to explore the capacity of the

E13 to detect differences in smaller samples. In order to gain

statistical power, it is possible that dependent data should be

used, including all four response options.

Conclusion

The findings support to some extent that the Bergen training model has a positive influence on the violence prevention and management climate on the wards from the

perspectives of both patients and staff. The findings also

show that the combination of the public health approach to

violence prevention and the City model may be a promising example of a new integrated theoretical framework

that could become a valuable contribution to the development of staff training. Considering the heavy reliance on

the use of incident rates as the outcome variable of staff

training, the inclusion of measurements such as the E13

scale could present a more nuanced picture of the effects of

training, especially because it includes ratings made by

patients. Furthermore, the use of more complex evaluation

variables is also congruent with the current view on multiple causes for inpatient violence. In addition, it may

provide valuable feedback to staff and management in the

efforts to establish a ward climate characterized by an

atmosphere of safety and security.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from AFA Insurance

(a non-profit organization owned by Swedens labour

market parties). We want to thank the patients and nurses

who took the time to participate in this study. We are also

grateful to the European Violence in Psychiatry Research

Group and to Charlotte Pollak for valuable discussions and

assistance in the research process.

403

A. Bjrkdahl et al.

References

one mental health unit: a pluralistic design.

Nijman H.L., aCampo J.M., Ravelli D.P., et al.

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health

(1999) A tentative model of aggression on inpa-

Nursing 9, 325337.

tient psychiatric wards. Psychiatric Services 50,

Abderhalden C. (2008) The systematic assessment

Duxbury J. (2003) Testing a new tool: the manage-

of the short-term risk for patient violence on

ment of aggression and violence attitude scale

acute psychiatric wards. Doctoral dissertation.

(MAVAS). Nurse Researcher 10, 3952.

832834.

Olofsson B. & Jacobsson L. (2001) A plea for

respect: involuntarily hospitalized psychiatric

Duxbury J. & Whittington R. (2005) Causes and

patients narratives about being subjected to

Beech B. & Leather P. (2006) Workplace violence

management of patient aggression and violence:

coercion. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental

in the health care sector: a review of staff train-

staff and patient perspectives. Journal of

ing and integration of training evaluation

Advanced Nursing 50, 469478.

Maastricht University, Maastricht.

models. Aggression and Violent Behavior 11,

2743.

Bjrkdahl A., Palmstierna T. & Hansebo G. (2010)

The bulldozer and the ballet dancer: aspects of

Health Nursing 8, 357366.

Paterson B., Leadbetter D. & Miller G. (2005)

Farrell G. & Cubit K. (2005) Nurses under threat:

Beyond Zero Tolerance: a varied approach to

a comparison of content of 28 aggression man-

workplace violence. British Journal of Nursing

agement programs. International Journal of

Mental Health Nursing 14, 4453.

14, 810815.

Paterson B., Ryan D. & McComish S. (2009)

nurses caring approaches in acute psychiatric

Field A. (2009) Discovering Statistics Using SPSS,

Research and Best Practice Associated with the

intensive care. Journal of Psychiatric and

3rd edn, pp. 699700. Sage Publications,

Protection of Staff from Third Party Violence

Mental Health Nursing 17, 510518.

London.

and Aggression in the Workplace A Literature

Bowers L. (2002) Dangerous and Severe Personal-

Flood C., Brennan G., Bowers L., et al. (2006)

ity Disorder. Reaction and Role of the Psychi-

Reflections on the process of change on acute

Paterson B., Leadbetter D., Miller G., et al. (2010)

atric Team. Routledge, London.

psychiatric wards during the City Nurse Project.

Re-framing the problem of workplace violence

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health

directed towards nurses in mental health

Nursing 13, 260268.

services in the UK: a work in progress. Interna-

Bowers L. (2009) Association between staff factors

and levels of conflict and containment on acute

psychiatric wards in England. Psychiatric

Services 60, 231239.

Hahn S., Needham I., Abderhalden C., et al.

(2006) The effect of a training course on mental

Review. NHS Health Scotland, Edinburgh.

tional Journal of Social Psychiatry 56, 310

320.

Bowers L., Brennan G., Flood C., et al. (2006a)

health nurses attitudes on the reasons of patient

Peplau H.E. (1997) Peplaus theory of interper-

Preliminary outcomes of a trial to reduce con-

aggression and its management. Journal of Psy-

sonal relations. Nursing Science Quarterly 10,

flict and containment on acute psychiatric

chiatric and Mental Health Nursing 13, 197

wards: City Nurses. Journal of Psychiatric and

204.

Mental Health Nursing 13, 165172.

162167.

Raubenheimer J. (2004) An item selection proce-

International Council of Nurses, Public Services

dure to maximise scale reliability and validity.

Bowers L., Simpson A., Eyres S., et al. (2006b)

International, World Health Organization &

SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 30, 5964.

Serious untoward incidents and their aftermath

International Labor Office (2005) Framework

Richter D. & Whittington R., eds (2006) Violence

in acute inpatient psychiatry: the Tompkins

Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence

in Mental Health Settings. Causes, Conse-

Acute Ward study. International Journal of

in the Health Sector The Training Manual.

Mental Health Nursing 15, 226234.

World Health Organization, Geneva.

quences, Management. Springer, New York.

Richter D., Needham I. & Kunz S. (2006) The

Bowers L., Flood C., Brennan G., et al. (2008) A

International Labor Office, International Council

effects of aggression management training for

replication study of the City nurse intervention:

of Nurses, World Health Organization & Public

mental health care and disability care staff:

reducing conflict and containment on three

Services

Framework

a systematic review. In: Violence in Mental

acute psychiatric wards. Journal of Psychiatric

Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence

Health Settings: Causes, Consequences and

and Mental Health Nursing 15, 737742.

in the Health Sector. International Labor Office,

Management (eds Richter, D. & Whittington,

Brennan G., Flood C. & Bowers L. (2006) Con-

International

(2002)

Geneva.

R.), pp. 211227. Springer, New York.

straints and blocks to change and improvement

Jarrett M., Bowers L. & Simpson A. (2008)

Rossberg J.I. & Friis S. (2003) A suggested revision

on acute psychiatric wards: lessons from the

Coerced medication in psychiatric inpatient

of the Ward Atmosphere Scale. Acta Psychiat-

City Nurses project. Journal of Psychiatric and

care: literature review. Journal of Advanced

Mental Health Nursing 13, 475482.

Nursing 64, 538548.

Council of Europe (2004) Recommendation,

Johnson M.E. (2010) Violence and restraint reduc-

Rec(2004)10 of the Committee of Ministers to

tion efforts on inpatient psychiatric units. Issues

Members States Concerning the Protection of

in Mental Health Nursing 31, 181197.

rica Scandinavica 108, 374380.

Steinert T. (2002) Prediction of inpatient violence.

Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement

106, 133141.

Stubbs B., Leadbetter D., Paterson B., et al. (2009)

the Human Rights and Dignity of Persons

Krug E.G., Dahlberg L.L. & Mercy J.A., et al., eds

Physical intervention: a review of the literature

with Mental Disorder. Council of Europe,

(2002) World Report on Violence and Health.

on its use, staff and patient views, and the

Strasbourg.

World Health Organization, Geneva.

impact of training. Journal of Psychiatric and

Delaney K.R. & Johnson M.E. (2006) Keeping the

Lutzen K., Blom T., Ewalds-Kvist B., et al. (2010)

unit safe: mapping psychiatric nursing skills.

Moral stress, moral climate and moral sensitiv-

Journal of American Psychiatric Nurses Asso-

ity among psychiatric professionals. Nursing

Violence

ciation 12, 198207.

Ethics 17, 213224.

Environment, AFS 1993:2. Arbetsmiljverket,

Mental Health Nursing 16, 99105.

Swedish Work Environment Authority (1993)

and

Menaces

in

the

Working

DeVellis R.F. (2003) Scale Development Theory

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2006)

and Applications. Sage Publications, Thousand

Violence the Short-term Management of

Vatne S. & Fagermoen M.S. (2007) To correct and

Oaks, CA.

Stockholm.

Disturbed/Violent Behavior in In-patient Psy-

to acknowledge: two simultaneous and conflict-

Duxbury J. (2002) An evaluation of staff and

chiatric Settings and Emergency Department.

ing perspectives of limit-setting in mental health

patient views of and strategies employed to

Clinical Practice Guidelines. Royal College of

nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental

manage inpatient aggression and violence on

Nursing, London.

Health Nursing 14, 4148.

404

2012 Blackwell Publishing

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Violence and Aggression in PsyDocument12 pagesViolence and Aggression in PsyMimerosePas encore d'évaluation

- Patient Safety in Psychiatric Inpatient Care A Literature ReviewDocument12 pagesPatient Safety in Psychiatric Inpatient Care A Literature ReviewcigyofxgfPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 3390@medicina55090553Document13 pages10 3390@medicina55090553diah fitriPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact - Ijranss-1. Ijranss - Length of Stay Reporting in Forensic Secure Care Can Be Augmented by An Overarching Framework To Map Patient Journey in Mentally Disordered Offender Pathway ForDocument38 pagesImpact - Ijranss-1. Ijranss - Length of Stay Reporting in Forensic Secure Care Can Be Augmented by An Overarching Framework To Map Patient Journey in Mentally Disordered Offender Pathway ForImpact JournalsPas encore d'évaluation

- Mentalizing and WorkingDocument14 pagesMentalizing and WorkingJuan David ArbelaezPas encore d'évaluation

- Post-Seclusion And/or Restraint Review in Psychiatry: A Scoping Review Article OutlineDocument27 pagesPost-Seclusion And/or Restraint Review in Psychiatry: A Scoping Review Article OutlineStudentnurseMjPas encore d'évaluation

- 41 72 1 SMDocument4 pages41 72 1 SMMisnan CungKringPas encore d'évaluation

- PTSD Nursing UCIDocument23 pagesPTSD Nursing UCITareas Express TECHPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study On Stress Management of Staff Working in Different Coronavirus Hospital at WuhanDocument9 pagesA Study On Stress Management of Staff Working in Different Coronavirus Hospital at WuhanshakeelPas encore d'évaluation

- Johnson2017 2Document35 pagesJohnson2017 2diah fitriPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Technology and Science EducationDocument10 pagesJournal of Technology and Science EducationClaire GalangquePas encore d'évaluation

- Selvin 2021Document8 pagesSelvin 2021Stella GašparušPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrative Literature CompletedDocument20 pagesIntegrative Literature Completedapi-431939757Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nurses' Adherence To Patient Safety Principles: A Systematic ReviewDocument15 pagesNurses' Adherence To Patient Safety Principles: A Systematic ReviewWidia Hertina PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Samikshya .EditedDocument8 pagesSamikshya .EditedSaru NiraulaPas encore d'évaluation

- 23-04-2021-1619164711-6-Impact - Ijranss-2. Ijranss - Length of Stay Reporting in Forensic Secure Care Can Be Augmented by An Overarching Framework To Map Patient Journey in MentallyDocument10 pages23-04-2021-1619164711-6-Impact - Ijranss-2. Ijranss - Length of Stay Reporting in Forensic Secure Care Can Be Augmented by An Overarching Framework To Map Patient Journey in MentallyImpact JournalsPas encore d'évaluation

- JMedLife-09-363Document6 pagesJMedLife-09-363Al FatihPas encore d'évaluation

- EHPS Abstracts 2014 A4Document225 pagesEHPS Abstracts 2014 A4Erika GomezPas encore d'évaluation

- Identifying and Developing Therapeutic Principles For Trauma Focused Work in Person-Centred and Emotion Focused TherapiesDocument31 pagesIdentifying and Developing Therapeutic Principles For Trauma Focused Work in Person-Centred and Emotion Focused TherapiesChih Chou ChiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: Safety and Protection For Nurses 1Document13 pagesRunning Head: Safety and Protection For Nurses 1api-239898998Pas encore d'évaluation

- Narganes Matias Arguello 1909319 Hs2135 ScriptDocument11 pagesNarganes Matias Arguello 1909319 Hs2135 ScriptMatías ArgüelloPas encore d'évaluation

- Simpson 2018Document7 pagesSimpson 2018Stella GašparušPas encore d'évaluation

- PDFDocument15 pagesPDFKarine SchmidtPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Nursing ResearchDocument7 pagesAsian Nursing ResearchWayan Dyego SatyawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessments in Psychotherapy With Suicidal Patients The Precedence of Alliance WorkDocument9 pagesAssessments in Psychotherapy With Suicidal Patients The Precedence of Alliance WorkMario VillegasPas encore d'évaluation

- Wampole 2020Document17 pagesWampole 2020rafaelcaloca1Pas encore d'évaluation

- 022 Use of Motivational Interviewing by Non-Clinicians in Non-Clinical Settings 2012Document15 pages022 Use of Motivational Interviewing by Non-Clinicians in Non-Clinical Settings 2012ISCRRPas encore d'évaluation

- Original Research Article Impact and Prevalence of Physical and Verbal Violence Toward Healthcare WorkersDocument7 pagesOriginal Research Article Impact and Prevalence of Physical and Verbal Violence Toward Healthcare WorkersÁngela María GuevaraPas encore d'évaluation

- 1444-Article Text-6655-1-10-20111214Document15 pages1444-Article Text-6655-1-10-20111214Akkash KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory&Variable DiscussionDocument11 pagesTheory&Variable DiscussionJustine Dinice MunozPas encore d'évaluation

- 2018 Article 9869Document29 pages2018 Article 9869Christian MolimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nur4322 - Irl Final 1Document17 pagesNur4322 - Irl Final 1api-533852083Pas encore d'évaluation

- ArtikelDocument14 pagesArtikelRetno WhatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Activity 1 and 2Document5 pagesActivity 1 and 2Dustin AgsaludPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Research Case 1Document7 pagesNursing Research Case 1yjdyv2z4zkPas encore d'évaluation

- Jan Revisions 7917Document28 pagesJan Revisions 7917Márcio Roberto TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Methodology 1Document11 pagesMethodology 1Latest Jobs In PakistanPas encore d'évaluation

- Effectiveness of Psychoeducational Program On Psychological Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery in Khartoum2017 639Document5 pagesEffectiveness of Psychoeducational Program On Psychological Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery in Khartoum2017 639Ishraga AlbashierPas encore d'évaluation

- 10Document9 pages10api-678571963Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Assignment PDFDocument5 pagesFinal Assignment PDFshanthiPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational Safety Climate and Workplace Violence Among Primary Healthcare Workers in MalaysiaDocument10 pagesOrganizational Safety Climate and Workplace Violence Among Primary Healthcare Workers in MalaysiaIJPHSPas encore d'évaluation

- Increasing Identification of Domestic Violence in Emergency DepartmentsDocument42 pagesIncreasing Identification of Domestic Violence in Emergency Departmentselisha OwaisPas encore d'évaluation

- Stress Management TechniquesDocument29 pagesStress Management Techniquesella joyce100% (3)

- Ffectiveness of Digital Interventions For: The E Psychological Well-Being in The Workplace: A Systematic Review ProtocolDocument12 pagesFfectiveness of Digital Interventions For: The E Psychological Well-Being in The Workplace: A Systematic Review ProtocolyuliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Alzh 1 ART Intervenciones Psicosocial y Conductual en Demencia-BurnsDocument5 pagesAlzh 1 ART Intervenciones Psicosocial y Conductual en Demencia-BurnsKitzia AveiriPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of stroke care education on burden and quality of lifeDocument30 pagesEffect of stroke care education on burden and quality of lifeMaryoma HabibyPas encore d'évaluation

- Quality Assurance and Patient Safety Measures: A Comparative Longitudinal AnalysisDocument8 pagesQuality Assurance and Patient Safety Measures: A Comparative Longitudinal AnalysisjyothiPas encore d'évaluation

- Personality Trait Relationship With Depression and Sucidal IdeationsDocument11 pagesPersonality Trait Relationship With Depression and Sucidal Ideationsaiza jameelPas encore d'évaluation

- Out 2Document7 pagesOut 2laodesyuhadarPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibliographyDocument8 pagesAnnotated BibliographyEunice AppiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy Benefit The Acute Patient Pathway: A Mixed-Methods StudyDocument12 pagesOccupational Therapy and Physiotherapy Benefit The Acute Patient Pathway: A Mixed-Methods StudyIlvita MayasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Coaching in Pharmacy Practice: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesHealth Coaching in Pharmacy Practice: A Systematic ReviewrujaklutisPas encore d'évaluation

- Intisari Permenkes No11 Tahun 2017Document8 pagesIntisari Permenkes No11 Tahun 2017Hari Putra PetirPas encore d'évaluation

- Problem-Based ResearchDocument8 pagesProblem-Based Researchapi-480618512Pas encore d'évaluation

- Infection Prevention by Nurses - EditedDocument6 pagesInfection Prevention by Nurses - EditedAllan DavisPas encore d'évaluation

- Predictors of Burnout Among Nurses: An Interactionist ApproachDocument7 pagesPredictors of Burnout Among Nurses: An Interactionist ApproachCANDYPAPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Artikel PSDocument6 pages5 Artikel PSNina 'Han Hyebyun' MereyunjaePas encore d'évaluation

- 17 BVSDocument35 pages17 BVSNydia Isabel Ruiz AntonioPas encore d'évaluation

- PICOT Question Research Critiques: Student's NameDocument8 pagesPICOT Question Research Critiques: Student's Namecatherine SitatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Workplace ViolenceDocument383 pagesWorkplace ViolenceAmeni Hlioui ChokriPas encore d'évaluation

- Bed Surge CapacityDocument7 pagesBed Surge CapacityfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Strengths JP's PartDocument3 pagesStrengths JP's PartfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Team Charter FormDocument1 pageTeam Charter FormfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Varkey QiDocument5 pagesVarkey QifairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Plan 2011 AbstractDocument19 pagesStrategic Plan 2011 AbstractfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- QIPDocument4 pagesQIPfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Detailed Requirements For Application Paper - Additional ThoughtsDocument10 pagesDetailed Requirements For Application Paper - Additional ThoughtsfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Outline For PaperDocument4 pagesOutline For PaperfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Growth SampleDocument2 pagesGrowth SamplefairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Care OrgDocument8 pagesHealth Care OrgfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Group's DiscussionDocument1 pageGroup's DiscussionfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Article Summaries July 9 1 AMFINALDocument7 pagesArticle Summaries July 9 1 AMFINALfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide To Case AnalysisDocument14 pagesGuide To Case Analysisheyalipona100% (1)

- Security IntegrationDocument14 pagesSecurity IntegrationfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- History Essay Outline: Impact of 9/11 On Canada-United States RelationDocument1 pageHistory Essay Outline: Impact of 9/11 On Canada-United States RelationfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- A New Border A Canadian PerspDocument12 pagesA New Border A Canadian PerspfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- History Essay Outline: Impact of 9/11 On Canada-United States RelationDocument1 pageHistory Essay Outline: Impact of 9/11 On Canada-United States RelationfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- One Decade After 911Document16 pagesOne Decade After 911fairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Security IntegrationDocument14 pagesSecurity IntegrationfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Essay RUBRICDocument1 pageFinal Essay RUBRICfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Counter TerrorismDocument19 pagesCounter TerrorismfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Hartman NSG Conflict CommunicationDocument13 pagesHartman NSG Conflict CommunicationfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact On TradeDocument3 pagesImpact On TradefairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ten Principles of Good Interdisciplinary Team Work: Research Open AccessDocument11 pagesTen Principles of Good Interdisciplinary Team Work: Research Open AccessfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Homelessness and Hope 8Document4 pagesHomelessness and Hope 8fairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- A New Border A Canadian PerspDocument12 pagesA New Border A Canadian PerspfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Bender Clincal Nurse ManagerDocument10 pagesBender Clincal Nurse ManagerfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Not Competing Was Strategy of Choice Used by NurseDocument3 pagesNot Competing Was Strategy of Choice Used by NursefairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- RubricDocument1 pageRubricfairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument12 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyGrit WingsPas encore d'évaluation

- M H Case SolutionDocument1 pageM H Case SolutionSai Dinesh UniquePas encore d'évaluation

- Care of High Risk Newborn - ChaboyDocument9 pagesCare of High Risk Newborn - Chaboychfalguera0% (1)

- Water Sealed DrainageDocument2 pagesWater Sealed DrainagefairwoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- 11th Zoology EM Practical NotesDocument11 pages11th Zoology EM Practical NotesBhavana Gopinath100% (1)

- ICU protocol 2015 قصر العيني by mansdocsDocument227 pagesICU protocol 2015 قصر العيني by mansdocsWalaa YousefPas encore d'évaluation

- Ross University 2010-2011 Pre-Residency Planning GuideDocument61 pagesRoss University 2010-2011 Pre-Residency Planning GuidescatteredbrainPas encore d'évaluation

- Ramadan NutritionDocument27 pagesRamadan NutritionselcankhatunPas encore d'évaluation

- Breast LumpDocument2 pagesBreast Lumplentini@maltanet.netPas encore d'évaluation

- Hospital Report PDFDocument28 pagesHospital Report PDFGaurav Chaudhary Alig100% (1)

- 108 Names of DhanvantariDocument7 pages108 Names of DhanvantaricantuscantusPas encore d'évaluation

- Aur VedaDocument4 pagesAur VedaLalit MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department - E-Cigarette E-Mails April 2011 Part 1Document292 pagesTacoma-Pierce County Health Department - E-Cigarette E-Mails April 2011 Part 1American Vaping AssociationPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of Push-Pull Osmotic Pump Tablets For A SlightlyDocument4 pagesDevelopment of Push-Pull Osmotic Pump Tablets For A SlightlyphamuyenthuPas encore d'évaluation

- Closed Tibia and Fibula Fracture Case PresentationDocument30 pagesClosed Tibia and Fibula Fracture Case Presentationzhafran_darwisPas encore d'évaluation

- CEO Administrator Healthcare Management in San Antonio TX Resume Robert WardDocument3 pagesCEO Administrator Healthcare Management in San Antonio TX Resume Robert WardRobertWard2Pas encore d'évaluation

- NCP Infection NewDocument3 pagesNCP Infection NewXerxes DejitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Niyog-Niyogan - Quisqualis Indica Herbal Medicine-Health Benefits-Side Effects PDFDocument4 pagesNiyog-Niyogan - Quisqualis Indica Herbal Medicine-Health Benefits-Side Effects PDFJikka RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Miss Evers Boys Draft 4Document2 pagesMiss Evers Boys Draft 4api-291172102Pas encore d'évaluation

- Adaptive Symptoms of RGP PDFDocument9 pagesAdaptive Symptoms of RGP PDFanggastavasthiPas encore d'évaluation

- SpeakingDocument3 pagesSpeakingThủy TrầnPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Personality in Sport and Physical ActivityDocument7 pagesThe Role of Personality in Sport and Physical ActivityWanRezawanaWanDaudPas encore d'évaluation

- Birtcher 774 ESU - User and Service Manual PDFDocument39 pagesBirtcher 774 ESU - User and Service Manual PDFLuis Fernando Garcia SPas encore d'évaluation

- Closing The Gap 2012Document127 pagesClosing The Gap 2012ABC News OnlinePas encore d'évaluation

- Pharyngitis Laryngitis TonsillitisDocument10 pagesPharyngitis Laryngitis Tonsillitisapi-457923289Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ateneo de Zamboanga University Nursing Skills Output (NSO) Week BiopsyDocument4 pagesAteneo de Zamboanga University Nursing Skills Output (NSO) Week BiopsyHaifi HunPas encore d'évaluation

- Contact AllergyDocument39 pagesContact AllergylintangPas encore d'évaluation

- Overcoming Low Self-Esteem Extract PDFDocument40 pagesOvercoming Low Self-Esteem Extract PDFMarketing Research0% (1)

- You Can Grow Your IntelligenceDocument6 pagesYou Can Grow Your IntelligenceSoniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Statement On Controlled Organ Donation After Circulatory DeathDocument10 pagesStatement On Controlled Organ Donation After Circulatory DeathHeidi ReyesPas encore d'évaluation