Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Arab Muslim Attitudes Toward The West - Furia - Lucas

Transféré par

Contributor BalkanchronicleTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Arab Muslim Attitudes Toward The West - Furia - Lucas

Transféré par

Contributor BalkanchronicleDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

International Interactions, 34:186207, 2008

Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0305-0629

DOI: 10.1080/03050620802168797

Arab Muslim Attitudes Toward the West:

Cultural, Social, and Political Explanations

1547-7444 Interactions,

0305-0629

GINI

International

Interactions Vol. 34, No. 2, May 2008: pp. 139

Arab

P.

A. Anti-Western

Furia and R. E.

Attitudes

Lucas

PETER A. FURIA

Department of Political Science, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA

RUSSELL E. LUCAS

Department of Political Science, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA

We utilize pooled data from Zogby Internationals 2002 Arab

Values Survey (carried out in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Kuwait,

Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and UAE) in order to test for cultural,

social and/or international political influences on Arab Muslim

attitudes toward Western countries (Canada, France, Germany,

UK, and USA). We find little support for cultural hypotheses to the

effect that hostility to the West is a mark-up on Muslim and/or Arab

identity. We find only limited support for social hypotheses that

suggest that hostility to the West is predicted by socioeconomic deprivation, youth, and/or being male. We find the strongest support

for a lone political hypothesis: hostility toward specific Western

countries is predicted by those countries recent and visible international political actions in regard to salient international issues

(e.g., Western foreign policies toward Palestine).

KEYWORDS Clash of Civilizations, Palestine, Arab, public

opinion, anti-Americanism.

Mark OKeefe (Executive Director, Pew Forum on Religion and Public

Life): You, of course, did not predict 9/11, but one could say that you did

predict the context in which a 9/11-type incident would emerge.

The authors are equally responsible for the contents of this article. The authors would like to thank the

Research Council and the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Oklahoma and the Jack D.

Gordon Institute of Florida International University for their support.

Address correspondence to Peter A. Furia, Assistant Professor Political Science, Wake Forest

University, Box 7568 Reynolda Station, Winston-Salem, NC 27109, USA. E-mail: furiapa@ wfu.edu

186

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

187

Samuel Huntington: I wouldnt argue with that.1

There are days that mark great historical divides, and Sept. 11, 2001, is

one of them. It isnt just what happened that day, but how the world has

changed since . . . There has been no peace since, only an uneven struggle

against terrorists who have killed thousands of innocent civilians in New York

and Washington, in Madrid and London, all in the name of Islam. It is

nothing less than a clash of civilizations. (Macdonald, 2006, p. A21)

Since the publication of Samuel Huntingtons 1993 Foreign Affairs article The

Clash of Civilizations (and his 1996 book of the same title which rendered his

argument empirically testable) academic political scientists have repeatedly

demonstrated that the civilizational fault lines mapped by Huntington fail to

explain patterns of militarized interstate conflict (Huntington, 1993, 1996,

2000; Henderson, 1997; Russett et al., 2000; Russet and Oneal, 2001, Chiozza,

2002). Since 9/11, however, media invocations of Huntingtons concept of a

clash of civilizations have become about five times more frequent than they

were prior to 9/11.2 Must academics simply accept that previous empirical

analyses of the clash thesis seem to have fallen on deaf ears? Perhaps. But

while International Relations scholars have thus far (reasonably) addressed

the clash thesis at the interstate-dyad level, they have not yet addressed the

narrower individual-level question with which post-9/11 popularizers of the

clash thesis are so concerned. Specifically, Macdonald and apparently

many others worry that due to particularly intensely-felt cultural identities,

Arab Muslim individuals are systematically hostile to the West as such.

Although the popular formulation of cultural hypotheses is not particularly

rigorous, we think that, given its prominence, it should be subjected to empirical evaluation alongside various social and political alternatives.

Insofar as the clash of civilizations hypothesis is seen as a hypothesis

about terrorism, we do not possess the type of behavioral data that would

allow us to directly evaluate it at the individual level in the manner that, e.g.,

Russett and Oneal (2001) and Chiozza (2002) have refuted Huntingtons more

general claims in regard to states. That is, although numerous data sources

allow us to test the claim that civilizational fault lines predict patterns of militarized interstate disputes (i.e., among the 200 or so current members of the

international state system), we have no parallel archive on the presence and

absence of individual terrorist behavior (i.e., among the 7 billion or so current members of humankind).3

Yet if, as per Huntington and his contemporary popularizers, our question concerns the attitudinal context in which a 9/11 type-incident would

emerge, our methodological options improve considerably. For 9/11

brought about a small wave of opinion research on Muslim attitudes toward

the West. Specifically, we now have several surveys about how Muslims

around the world feel about the United States, a few of which also inquire

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

188

P. A. Furia and R. E. Lucas

into attitudes toward other Western countries, and at least one of which

also measures attitudes that might plausibly be interpreted as indicative of

civilization consciousness.

Thus, if the question is whether Arab Muslim civilization consciousness

in particular promotes hostility to Western civilization in particular, we can

utilize public opinion data to test whether that observation is correct. In other

words, we can examine whether the intensity of Arab Muslims ethnic and

religious identifications serve as a predictor of their hostility to the West.4

Alternatively, we can examine whether Arab Muslim attitudes toward the

West are better predicted by various social and/or (international) political

hypotheses (Lipset, 1968; Gurr, 1970; Skocpol, 1979; Kaplan, 1994; Friedman,

1999; Chomsky, 2001; Wright, 2002; Furia and Lucas, 2006; Urdal, 2006).

While we are not the first to examine Islamic and/or Arab consciousness in conjunction with social and political variables drawn from wellestablished social science paradigms such as modernization theory and

rational choice theory, most scholars who have previously done so have

been Comparative Politics scholars primarily interested in domestic political

questions.5 Mark Tessler is a partial exception. In addition to using survey

data to explore the relationship between Islam and attitudes toward democracy (Tessler, 2002), he also examines the relationship between what he

calls identification with politicized Islam and foreign policy preferences

(Tessler, 2003; Tessler and Nachtwey, 1998). He finds that politicized

Islamic attitudes do have a bearing on attitudes toward democracy and

foreign countries, while personal Islamic piety does not.6

Our analysis can also in some respects be seen as picking up where Furia

and Lucas (2006) leave off in our broadly rationalist (or, at least, political)

account of the determinants of Arab foreign policy opinion. We there examine

frequency tables from the Zogby International 2002 Arab Values Survey in

order to assess how prevailing opinion in each country surveyed stands in

regard to the thirteen non-Arab countries that the survey asks about. While circumspect about what this analysis of 91 subject-country/object country dyads

can tell us, they argue that prevailing Arab opinions about Western countries

have little to do with a clash of civilizations and much to do with specific countries concrete foreign policy behaviors in the region (Furia and Lucas, 2006).7

We here ask whether, all else equal, Arab Muslim individuals with high

levels of Muslim or Arab civilization consciousness are systematically hostile

to countries that Huntington counts as Western. If so, then the post-9/11

popularization of the clash of civilizations thesis will be understandable.

While Huntingtons critics might still claim that broad-based Arab-Muslim

hostility toward the West qua the West is unrelated to terrorism, they

could not then easily deny that such hostility exists. If, on the other hand,

Arab-Muslim civilization-consciousness turns out to be unrelated to or, for

that matter, even positively related to amity for the West, then the post-9/11

upsurge in clash of civilizations chatter will seem unfortunate indeed.

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

189

THEORY AND HYPOTHESES

Although the present analysis was in large part motivated by the post-9/11

popularization of the clash of civilizations thesis, and while we think

the novelty (or notoriety) of that thesis deserving of special attention, we by

no means wish to suggest that it is more significant than the relatively familiar social and political hypotheses in conjunction with which we evaluate it. Specifically, we here evaluate six distinct hypotheses about the

sources of Arab-Muslim attitudes toward the West, only two of which are

cultural in character. Three of the six, which we group under the rubric of

social explanations, are closely related to well-established modernization

school and/or Marxist school theories of comparative politics (see, e.g.,

Lipset, 1968; Gurr, 1970; Skocpol, 1979; Inglehart, 1997). A final political

hypothesis is exemplary of both classical realist and contemporary rationalist hypotheses on international politics (see, e.g., Morgenthau, 1954;

Waltz, 1979; Mearsheimer, 1990).

That said, our first hypothesis does attempt to capture precisely what

most popular commentators refer to when they credit Huntingtons clash of

civilizations thesis for its early recognition of the background ideational

context responsible for terror attacks by (Arab) Muslims against the West

in particular:7

Hypothesis 1: (Arab) Muslims who possess high levels of Islamic consciousness

will be systematically hostile toward Western countries in general.

We place parentheses around the word Arab because, despite the fact that

Huntington draws multiple fault lines within other religious traditions, he

has for the most part stressed the relative cohesiveness of Islamic civilization as a whole.8 Insofar as he and others continue to do so, therefore, our

analytic focus on Arab Muslims in particular must be justified by data limitations rather than by basic theoretical considerations.9

It is nonetheless important to note that the decisions that survey

research and grant-making organizations make about what to study are

likely influenced by the same popular preconceptions that we examine in

our paper. In particular, the fact that all 19 of the 9/11 hijackers were not

only Muslims but Arabs has inspired not just Arab-specific data but Arabspecific explanations of Muslim hostility to the West. Put another way, the

limitations of our data with respect to Hypothesis 1 may actually be viewed

as an asset with respect to Hypothesis 2:

Hypothesis 2: Arab Muslims who possess high levels of Arab consciousness

will possess systematically negative attitudes toward Western

countries in general.

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

190

P. A. Furia and R. E. Lucas

One might attribute this slight variation on the clash thesis to various

public intellectuals, including Irshad Manji (2005), Fareed Zakaria (2003)

and Fouad Ajami (2006). For Manji, it is not so much Muslims in general

but Arab-Muslims influenced by the sturdy customs [of] . . . Arab warriors, who are systematically bellicose and/or hostile to non-Arabs (Manji,

2005, p. 143). In Zakarias view as well, Muslim hostility to the West is

centered in the Middle East, deriving less from Islam than from a continuing tendency of Arabs to embrace patriarchy, strongmen [and] romanticism and to thus remain stuck in primitive political and social

arrangements (Zakaria, 2003, p. 131). Fouad Ajami, for his part, (2006,

p. xi) avers that a culture of terrorism has put down roots in Arab

lands. Ajami continues,

It was not an isolated band of misguided young men who came Americas

way on 9/11. They emerged out of the Arab worlds dominant culture

and malignancies. There were the financiers who subsidized the terrorism. There were the intellectuals who winked at the terrorism and justified

it. There were the preachers from Arabia to Amsterdam and Finsbury

Park who gave it religious sanction and cover. And there were the

Arab rulers whose authoritarian orders produced the terrorism and

who looked away from it so long as it targeted foreign shores (Ajami

2006, p. xii).

As none of these commentators goes so far as to argue that Islam has

nothing to do with hostility to the West (or, for that matter, that Arab Christians

do have anything to do with it) we regard Hypothesis 2 as a friendly

amendment to Hypothesis 1. Moreover, by only examining Arab consciousness on the part of Arab Muslims, we avoid the methodological

complications of attempting to simultaneously test Hypotheses 1 and 2 on

different samples.10

Perhaps the best known set of alternative hypotheses about ArabMuslim hostility to the West can be grouped under the rubric of social

explanations. A wide range of contemporary commentators, for example,

have suggested that hostility to the West is a mark-up on individual-level

socioeconomic deprivation (Friedman, 1999; Chomsky, 2001; Sardar and

Davies, 2002; Wright, 2002). Echoing well-known general theories of why

men rebel against their own governments (Lipset, 1968; Gurr, 1970;

Skocpol, 1979; Inglehart, 1997), these contemporary commentators suggest

that relatively low socioeconomic status is likewise a predictor of Arab

hostility toward the economically powerful West. Conversely, individuals

higher in socioeconomic status, and, in particular, relatively well-educated

individuals, are thought not only to be less willing to rebel against their own

governments but more accepting of international cultural differences.

Broadly speaking, the main difference between modernization and Marxist

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

191

theorists concerns not whether they think that non-Western elites are

systematically friendly to the West, but rather, whether or not they think

such friendliness is justified (Friedman, 1999; Sardar and Davies, 2002).

Hypothesis 3: Arab-Muslims lower in socioeconomic status will possess

systematically hostile attitudes toward the West.

Closely related to the hypothesis that the clash of civilizations is really

a clash of economies is the claim that it is most properly a clash of generations (Kaplan, 1994; Friedman, 1999; Wright, 2002; Urdal, 2006). On this

view, a population boom has led to meager economic prospects for youth

in Arab and other developing countries, and, in turn, made youth systematically hostile toward powerful status quo actors in domestic and international politics (Kaplan, 1994). Although some of the same modernization

school authors noted above argue that youth are more comfortable with

globalization and foreignness than are their elders (Inglehart, 1997; Norris,

2000), the predominant view of authors writing specifically on Arab-Muslim

youth seems well-represented by Hypothesis 4:

Hypothesis 4: Arab-Muslim youth will be systematically hostile to the West.

A final set of social explanations for Arab-Muslim hostility toward the

West might cautiously be termed socio-biological (Fukuyama, 1998;

Farrington, 1999; Wright, 2002; Manji, 2005; Inglehart and Norris, 2003; Ajami,

2006; Rizzo et al., 2007).11 For these authors, it is Arab-Muslim men in particular

who are likely to express anger and hostility toward the outside world.

Hypothesis 5: Arab-Muslim males will be systematically hostile to the West.

Despite the familiarity of Hypothesis 5, prior research on the (in)significance of attitudinal gender differences in the Middle East suggests that its

confirmation is particularly unlikely (Tessler et al., 1999).

In our view, the fact that Arab publics have quite favorable attitudes

toward some Western countries (e.g., France), yet very unfavorable attitudes toward others (e.g., the United States), makes all of the aforementioned explanations of these attitudes problematic. We are thus most

sympathetic to those scholars who see amities and enmities as a mark-up

on political rather than cultural or social variables (Morganthau,

1954; Waltz, 1959, 1979; Page and Shapiro, 1992; Holsti, 1996). In the context of the Cold War, for example, Ole Holsti concluded that Americans

evaluated the USSR more on what the Soviets did rather than who they

were. (1996, p. 78 emphasis in the original). The assertion that Arab

Muslims similarly evaluate Western countries on the basis of their concrete

foreign policy actions in the Middle East is of course a well-known

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

192

P. A. Furia and R. E. Lucas

alternative to the view that Arab Muslims are hostile to Westerners qua

Westerners because of who they are.

Tessler, Nachtwey, and Grant (1999), for example, argue that individual

Arab attitudes about the IsraeliPalestinian conflict do far more to predict

attitudes about regional peace than do sociological factors such as gender.

Similarly, in our dyad level analysis, Furia and Lucas (2006) argue that

Arab societies evaluate non-Arab societies largely on the basis of relatively

recent and specific foreign policy behaviors (Furia and Lucas, 2006, p. 599,

see also Telhami, 2002). While the above authors are more likely to invoke

realist theories of international relations than rationalist claims about differing ideal points in regard to specific foreign policy issues, the underlying

implication is essentially the same: Muslim Arabs possess concrete political

objections to the regional foreign policies of (some) Western countries, and,

in turn, it is only logical that they would evaluate those countries less favorably than they would countries that pursue policies of which they approve.

What no one has as yet tested, however, is whether the intensity of

Arab individuals preferences about foreign policy issues is in fact determinative of their attitudes toward Western countries active in the region.

With Hypothesis 6, we formalize and generalize the claim that individual

Arab Muslims concerned with a specific foreign policy issue (i.e., the

IsraeliPalestinian conflict) will evaluate countries not on the basis of who

they are but on the basis of what they do in regard to that issue.

Hypothesis 6: Muslim-Arabs who care about a specific foreign policy issue will

assess individual Western countries on the basis of that countrys

actions regarding that issue.

DATA AND VARIABLES

If we only wanted to examine Muslim attitudes toward America in particular

we would have no dearth of data, including many well-known surveys on

anti-Americanism by Pew, Gallup, and others. However, if we do not

consider the U.S. alone as an appropriate proxy for Huntingtons West, we

are limited to surveys and/or parts of surveys of Arab publics in particular,

only a few of which operationalize anything even vaguely resembling

civilization consciousness.12 We have thus turned to the 2002 Arab Values

Survey (AVS) conducted by Zogby International (Zogby, 2002).13 Zogby

asked respondents in seven sovereign Arab countries (Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon,

Kuwait, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and UAE) about their attitudes toward

thirteen non-Arab countries.14 Given that we are here concerned with post9/11 reformulations of the clash thesis, we naturally focus on attitudes

among Muslim Arabs, in particular toward the five object countries queried

about on the survey that Huntington categorizes as Western (e.g., Canada,

193

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

TABLE 1 Percentage Favorable Evaluations of Western

Object Countries (Pooled Sample of Muslim-Arab

Respondents to the AVS)

France

Germany

Canada

UK

USA

1,733

1,397

1,365

839

601

62.16

50.11

48.96

30.09

21.56

France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States).15 As all seven

of the sovereign Arab subject countries in which the surveys were carried

out possess a Muslim-majority population, filtering out non-Muslims only

slightly reduces sample-size, leaving us with an N of 2,788 Muslim Arab individuals for our pooled analysis.16

Our dependent variables consist of a series of five dichotomous variables

coded 1 if a respondent expressed either a very favorable or somewhat

favorable attitude toward the specific Western object country and 0 if a

respondent expressed a somewhat unfavorable or very unfavorable opinion.17 Table 1 depicts the percentage of individual Arab-Muslim respondents

in the pooled dataset that provided favorable evaluations of each country.

One of the great assets of the 2002 AVS is that it provides four different

measures of Islamic and Arab consciousness, each of which we analyze

in a separate logistic regression model. We see no clear-cut theoretical or

methodological reason for preferring one of these measures to another.18 We

thus designate as Model 1 the model which happens to come closest to providing post-9/11 invocations of the clash thesis with some empirical

justification: namely, the model that operationalizes Islamic and Arab

consciousness as a willingness to express a predominant sense of selfidentification as Muslim or Arab to an American (specifically to select either

of these self-identifications as the most important). Model 2 concerns

the willingness to express the same predominant sense of identification

to an Arab from another Arab country. Model 3 also examines identityconsciousness as respondents would express it to another Arab, but measures

respondents levels of identity-consciousness on a five-point scale ranging

from 1, representing a perception that a given identity category is not at all

important, for the respondent to 5 for its being very important. Finally,

Model 4 also assesses levels of identity consciousness, but, like Model 1, asks

the respondent to envision talking with someone from the United States.19

Among our three sociological hypotheses, only the socioeconomic

hypothesis is problematic to test in the context of the AVS. Due to the lack

of an AVS question on income, we must measure socioeconomic status with

reference to respondent education alone.20 Specifically, we use Zogbys

variable q903, for which completion of elementary education is coded as 1,

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

194

P. A. Furia and R. E. Lucas

completion of middle school is coded as 2, completion of high school

is coded as 3 and completion of university is coded as 4. Importantly,

inclusion of the education variable also allows us to control for the surveys

self-admitted (see Zogby, 2002, p. 99) coverage and response-biases vis a

vis relatively well-educated respondents. Assessing the socio-demographic

hypothesis (Hypothesis 4) presents no major difficulties, though it is worth

noting that Zogby only surveyed respondents between the ages of 21 and

64 (variable q701). We thus decided to create an age by decades variable

ranging from 1 to 5 and measuring whether a respondent was in their

twenties, thirties, forties, fifties or sixties. Per Hypothesis 5, we simply code

respondent gender (variable q22 in the AVS) as 0 for female and 1 for

male.

Last but not least, we operationalize our broadly political hypothesis

in relation to the issue of Palestine (the most concrete foreign policy issue

about which AVS respondents are asked). Specifically, respondents are

asked about the level of importance they personally attribute to the issue

of Palestine (q23), a variable measured on the same positive 1 to 5 scale as

that used for the level of consciousness variables. As suggested above,

however, Hypothesis 6 will most clearly be an improvement on the other

five hypotheses if and only if it turns out that individual-level concern for

Palestine is associated with differential evaluations of different Western

countries. Following Furia and Lucas (2006), we hypothesize that France

might be seen as playing a significant and relatively positive role in the

IsraeliPalestinian conflict, the U.S. and the UK as playing a significant and

negative role, and Canada and Germany as playing a role that is neither significantly positive nor negative. In order for Hypothesis 6 to be supported,

therefore, individual levels of concern for Palestine should turn out to be a.)

systematically positively related to attitudes toward France; b.) systematically

negatively related to attitudes toward the U.S. and the UK; and c.) unrelated

to attitudes toward Canada and Germany.

Finally, our analysis controls for the fact that, particularly in the Gulf

states, Arab and/or Muslim civilization consciousness might be particularly

appealing to guest-worker respondents who are not citizens of the country

in which they were queried. Specifically, we include a dichotomized version

of the original AVS variable q924, which measures whether a respondent to

the survey is a citizen of the particular Arab country in which the survey

was conducted.21

RESULTS

Tables 25 each provide summary statistics for five different logistic regression

equations (e.g., one equation per Western object country). Specifically, each

table presents a coefficient estimate, a standard error for the coefficient in

195

* .10; ** .05; *** .01.

LR chi2(7)

Pseudo R2

N

Islamic Consciousness

Arab Consciousness

Education

Age by decades

Male

Palestine (importance of)

Citizen (of subject country)

Constant

73.40***

.025

2380

.233 (.122)*

.564 (.108)***

.099 (.055)*

.176 (.050)***

.129 (.091)

.226 (.057)***

.070 (.152)

1.298 (.369)***

.107 (.129)

.579 (.118)***

.185 (.059)***

.140 (.054)***

.067 (.100)

.230 (.052)***

.060 (.173)

.856 (.396)**

68.66***

.026

2503

UK

USA

15.83***

.005

2427

.324 (.124)***

.001 (.105)

.019 (.053)

.001 (.047)

.078 (.088)

.093 (.056)*

.074 (.144)

.178 (.354)

France

95.57***

.030

2313

.035 (.124)

.774 (.107)***

.057 (.053)

.101 (.046)**

.001 (.088)

.032 (.058)

.290 (.144)**

.920 (.362)**

Germany

61.24***

.020

2270

.031 (.124)

.438 (.106)***

.000 (.055)

.110 (.046)**

.353 (.088)***

.028 (.058)

.269 (.145)*

.756 (.363)**

Canada

TABLE 2 Model 1 Predominant Civilization Consciousness as Expressed to an American and Other Predictors of Individual Muslim-Arab Attitudes

toward Various Western Object Countries

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

196

* .10; ** .05; *** .01.

Islamic Consciousness

Arab Consciousness

Education

Age by decades

Male

Palestine (importance of)

Citizen (of subject country)

Constant

LR chi2(7)

Pseudo R2

N

.147 (.123)

.396 (.155)***

.180 (.059)***

.122 (.055)**

.064 (.100)

.280 (.058)***

.060 (.172)

.868 (.385)**

62.32***

.024

2477

USA

.082 (.156)

.429 (.103)***

.103 (.055)*

.157 (.050)***

.112 (.091)

.265 (.057)***

.067 (.153)

1.293 (.368)***

69.50***

.023

2353

UK

.412 (.155)***

.518 (.099)***

.034 (.054)

.010 (.048)

.059 (.089)

.061 (.057)

.030 (.147)

.184 (.361)

33.53***

.011

2400

France

.218 (.167)*

.375 (.099)***

.064 (.053)

.075 (.046)

.010 (.088)

.072 (.057)

.213 (.144)

.883 (.340)

42.99***

.014

2286

Germany

.084 (.117)

.014 (.098)

.013 (.053)

.111 (.047)**

.329 (.088)***

.057 (.057)

.252 (.145)*

.721 (.363)**

30.09***

.010

2246

Canada

TABLE 3 Model 2 Predominant Civilization Consciousness as Expressed to an Arab and Other Predictors of Individual Muslim-Arab Attitudes

toward Various Western Object Countries

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

197

* .10; ** .05; *** .01.

Islamic Consciousness

Arab Consciousness

Education

Age by decades

Male

Palestine (importance of)

Citizen (of subject country)

Constant

LR chi2(7)

Pseudo R2

N

.151 (.049)***

.012 (.051)

.171 (.058)***

.145 (.054)***

.107 (.099)

.306 (.057)***

.031 (.166)

.290 (.398)

55.52***

.020

2598

USA

.215 (.044)***

.019 (.047)

.071 (.055)

.188 (.049)***

.063 (.090)

.324 (.057)***

.025 (.147)

.424 (.379)

84.06***

.027

2467

UK

.015 (.039)

.110 (.043)***

.009 (.053)

.005 (.046)

.045 (.087)

.057 (.055)

.129 (.140)

.042 (.363)

13.65***

.004

2516

France

.205 (.039)***

.050 (.043)

.041 (.053)

.116 (.045)***

.073 (.086)

.142 (.057)**

.138 (.138)

.041 (.367)

66.59***

.020

2390

Germany

.162 (.039)***

.139 (.043)***

.043 (.053)

.116 (.046)**

.280 (.087)***

.131 (.057)**

.111 (.140)

.285 (.373)

89.11***

.028

2347

Canada

TABLE 4 Model 3 Levels of Civilization Consciousness as Expressed to an Arab and Other Predictors of Individual Muslim-Arab Attitudes Toward

Various Western Object Countries

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

198

* .10; ** .05; *** .01.

LR chi2(7)

Pseudo R2

N

Islamic Consciousness

Arab Consciousness

Education

Age by decades

Male

Palestine (importance of)

Citizen (of subject country)

Constant

47.69***

.018

2591

.080 (.041)*

.026 (.047)

.169 (.058)***

.152 (.054)***

.090 (.098)

.278 (.056)***

.104 (.163)

.489 (.395)

USA

63.82***

.021

2463

.129 (.037)***

.024 (.043)

.065 (.055)

.190 (.049)***

.090 (.089)

.271 (.055)***

.099 (.145)

.642 (.376)*

UK

25.92***

.008

2386

.025 (.034)

.056 (.040)

.077 (.053)

.123 (.045)***

.038 (.085)

.083 (.056)

.307 (.134)**

.484 (.368)

.059 (.035)*

.116 (.040)***

.025 (.053)

.013 (.046)

.054 (.087)

.088 (.054)

.034 (.137)

.157 (.065)

12.32***

.004

2510

Germany

France

43.26***

.013

2344

.011 (.034)

.065 (.040)

.004 (.053)

.123 (.045)***

.335 (.086)***

.063 (.057)

.297 (.136)**

.347 (.372)

Canada

TABLE 5 Model 4 Levels of Civilization Consciousness as Expressed to an American and Other Predictors of Individual Muslim-Arab Attitudes

Toward Various Western Object Countries

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

199

parentheses, and an indication of that coefficients statistical significance (if

any) as measured by a two-tailed t test. At the bottom of each table, we list

the Model N, the likelihood ratio for the model (degrees of freedom in

parentheses) and a Pseudo R2 (McFadden) statistic of model fit. Given a

total of twenty-different equations to estimate we do not here present

predicted probability graphs. All models were estimated using Stata 9.

It should come as no surprise that the apparent effects of civilization

consciousness are fairly sensitive to the different ways in which civilization consciousness is operationalized in our four models. Even so, none

of the four models uncovers support for Hypothesis 1, which posits that

Islamic consciousness will exert a systematic negative effect on attitudes toward Western countries. In Model 1, this hypothesis receives borderline statistically significant support in regard to attitudes toward the

UK alone but fails to have even the predicted sign in regard to attitudes

toward either Canada or France. Indeed, as far as attitudes toward France

are concerned, Islamic consciousness shows up as a highly statistically

significant and positive predictor. More surprising to us is the consistency

of the evidence against Hypothesis 1 in Models 24. Specifically, it strikes

us as quite devastating to the reformulated clash thesis that 14 of 15 relevant coefficients exhibit a relationship in the direction opposite that predicted by Huntington (and that 5 of these 15 relationships are statistically

significant).

Hypothesis 2, in regard to Arab consciousness, fares considerably

better in Model 1 (receiving statistically significant support in regard to

all Western object countries except France). In Model 2, however, it finds

support only in regard to the U.S., the UK, and Germany, and is systematically contradicted in regard to France. Moreover, if not quite to the extent as

is Hypothesis 1, it too is repeatedly contradicted in Models 3 and 4. Specifically, it receives no statistically significant support, fails to so much as

correctly predict the sign of 7 out of 10 relevant coefficients, and predicts

relationships exactly opposite the highly statistically significant observed

relationships in 3 out of 10 instances (specifically, attitudes about Canada in

Model 3 and attitudes about France in Models 3 and 4).

Similarly, Hypothesis 3 is not merely unsupported but, in some

instances, systematically contradicted. As with the effects of Muslim identity

and Arab identity on attitudes toward the West, the effects of educational

attainment on attitudes toward the West are contingent on the particular

Western object country asked about. Only with respect to attitudes toward

Canada is the relationship between education and amity for Western

countries consistently in the predicted positive direction (and it never rises

to the level of even borderline statistical significance). Nor is there any

statistically significant relationship in any of the four models between

educational attainment and attitudes toward France or Germany. Educational attainment is, however, systematically negatively-related to attitudes

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

200

P. A. Furia and R. E. Lucas

toward the United States across all models. (It also shows up as a borderline

significant negative predictor of attitudes toward the UK in Models 1 and 2.)

Hypothesis 4, the socio-demographic hypothesis, receives still less

support, and is in fact systematically contradicted in 11 out of 20 possible

cases. As 18 of 20 relationships are in the direction opposite that predicted

by the angry Arab youth hypothesis, it would appear that, if anything, it is

older Arab Muslims who are systematically hostile to the West. While

this overall pattern is consistent with the aforementioned modernizationtheoretic claims about a universal tendency of young people to be relatively

open to foreignness and/or to think of themselves as global citizens

(Norris, 2000), the fact that the two cases that buck the general trend are

cases involving France suggests considerable interpretive caution. We discuss

this matter further below.

Nor, finally, does the socio biological hypothesis find anything more

than idiosyncratic supportspecifically, in terms of the consistently and systematically negative attitudes of Arab Muslim men toward Canada (and only

Canada).22 No other relevant coefficients for this hypothesis are statistically

significant, and indeed, only 8 of the other 16 are in the direction predicted

by the hypothesis. Particularly surprising to those who might predict that

the United States would be the primary recipient of Arab male anger is the

fact that, while it is certainly the primary recipient of Arab anger, maleness

is a positive (though not significant) predictor of attitudes toward the United

States across all four models.

Particularly in contrast to the five hypotheses discussed so far, Hypothesis 6

fares very well across all four models. For example, we find that individuallevel support for Palestine is always a highly-statistically significant negative

predictor of attitudes toward the U.S. and the UK, and the hypothesis also

correctly predicts the sign of respondent attitudes toward France in all four

cases. Particularly as Hypothesis 6 is our own favored hypothesis, however,

it is important to concede that the coefficients in regard to France are only

borderline statistically significant in one of the four models, and, moreover,

that two of the eight coefficients that Hypothesis 6 predicts should not

exhibit statistically-significant coefficients do in fact do so: namely, those

pertaining to Canada and Germany in Model 3.

DISCUSSION

Whereas other analyses have discredited Samuel Huntingtons clash of civilizations thesis as a global nomothetic theory of militarized interstate conflict,

our results in regard to Hypothesis 1 discredit those ad hoc post-9/11 reformulations of the thesis that, with Huntingtons blessing, have gained even

more prominence than did the original global theory. Specifically, we have

demonstrated a complete lack of support for the hypothesis that Islamic

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

201

consciousness predicts hostility toward the West and at least a modicum of

support for the counterhypothesis that it in fact predicts amity for Western

countries. As with all of our hypotheses, however, much depends on the

particular way in which civilization consciousness is operationalized and,

above all, the particular Western country about which Arab publics are asked.

We draw a similar conclusion in regard to the related hypothesis that

Arab consciousness predicts hostility to the West. If the Western countries

in question are the United States and the United Kingdom, it must be conceded that two of the four models uncover support for the hypothesis. Yet

if the Western country in question is France, a full three of the four models

argue systematically against it. In other words, Arab consciousness is systematically predictive of amity for one of the very countries whose historical

role in the region would seem most insulting to the backward-looking

traditionalists thought to inhabit it. Thus, while the role of Arab consciousness in the region certainly appears worthy of future research, we recommend that that research take a different tack than the one suggested by,

e.g., Ajami, Manji, and Zakaria.

At first blush, the considerable evidence against Hypothesis 3 constitutes a rather direct refutation of the hypothesis that socioeconomic frustration is determinative of hostility to out-groups. To say nothing of the likely

presence of systematically higher acquiescence effects among lower education respondents to the survey, however, we must recall that some proponents of the socioeconomic frustration hypothesis posit that it is precisely

highly-educated low-income individuals who will be most likely to harbor

hostility (Ibrahim, 1980; Wright, 2002; Espositio and Mogahed, 2008; see

also Hafez, 2004, p. 9). In any event, while we look forward to future surveys that might allow researchers to explore various possible relationships

between income and education as potential predictors of Arab attitudes

toward foreign countries, we are ourselves particularly struck by the fact

that the role of education in the data we have is highly contingent on

the country in question: specifically, higher educational attainment is only

systematically predictive of hostility to the United States and the United

Kingdom the two countries that those who follow contemporary foreign

policy closely would be least likely to consider friendly to the region.

With respect to Hypothesis 4 as well, we would again emphasize the

distinction between attitudes toward the US and the UK on the one hand

(the two countries significantly favored by younger respondents across all

four models), and France (the one country never significantly favored by

younger respondents in any of the models). Obviously, our unrepeated

cross-sectional data cannot speak to general debates about whether these

patterns might be best interpreted as age and/or cohort effects, nor, of

course, can we do anything more than highlight the fact that those one

might expect to be most resentful of a former imperial power appear least

so. Our findings are, however, quite sufficient to refute the claim that

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

202

P. A. Furia and R. E. Lucas

the Middle East features a generation of angry Arab youth systematically

hostile to the West.

Our results in regard to Hypothesis 5 suggest a variation on a similar

theme in that the distinction between the US and the UK on the one hand

and France on the other appears to have been replaced by a distinction

between the U.S. alone on the one hand and Canada (the lone object country in regard to which we uncover statistically significant relationships) on

the other. As far as theory is concerned, a sociobiological account that is

particular to attitudes about Canada seems a contradiction in terms, and we

know of no account of gender socialization patterns that would exclusively

affect attitudes toward Canada either. To be sure, of the five countries asked

about, Canada is probably the one most likely to be characterized as having

a Venutian foreign policy (and the U.S. as the most likely to be characterized as having a Martian one) but we in any case leave this matter to

future researchers.

The one hypothesis about determinants of Arab attitudes toward

the West that is supported is the quintessentially political one: namely,

Muslim-Arabs who care about a specific foreign policy issue do seem

to assess individual Western countries on the basis of that countrys

recent and visible actions in regard to that issue. Our operationalization

of this hypothesis solely in reference to the issue of Palestine is of

course preliminary, but we hope that its relative success will encourage

others to test related hypotheses more rigorously. Particularly in conjunction with the lack of consistent support for the other hypotheses here

tested, we conclude a.) that Arab attitudes toward the West vary greatly

depending on the particular Western country in question and b.) that

politics explains more of that variation than does either society or

culture.

CONTRIBUTORS

Dr. Peter A. Furia is an assistant professor of Political Science at Wake Forest

University.

Dr. Russell E. Lucas is an assistant professor of Political Science at Florida

International University.

NOTES

1. August 18, 2006 interview with Samuel Huntington. Full text available at Pew (2006c).

2. Per a Lexis-Nexis search of the content of major newspapers from 19962000 and 20022006.

3. One well-known solution to this problem involves selecting on the dependent variable of

participation in terrorist acts and thereafter attempting to impute why those who participated in terrorism

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

203

did so (Pape, 2003; see also Ibrahim, 1980). Whatever the reasonableness of these imputations, however,

it is clear that this approach tells us nothing about how levels of what Huntington calls civilization

consciousness among terrorists compare to those of non-terrorists (Huntington, 1996, pp. 36, 266271).

In turn, extant critiques of the view that individual terrorist behavior is unrelated to a clash of civilizations are not decisive.

4. In part because of its limited geographical scope, and in part because it seeks only attitudinal evidence of inter-civilizational clash, our test of Huntingtons thesis seems to us in many ways a

more generous one than previous behavioral analyses conducted by scholars of international politics

(Henderson, 1997; Russett et al., 2000; Russet and Oneal, 2001; Fox, 2001; Chiozza, 2002; Pape, 2003;

Roeder, 2003; Tusicisny, 2004).

5. Note also that, unlike some other scholars, Huntington does not argue that individual religious conviction or piety itself promotes hostility to out-groups (see, e.g., Harris, 2005). Although he

comes close to suggesting that Muslim piety in particular does so (see also Hirsi Ali, 2006; Hitchens,

2006), preliminary analyses of the 2002 Arab Values Survey data, if anything, support the opposite

view. The more general relationship between piety and international-policy preferences is certainly worthy of empirical study (preferably not limited to Muslim countries alone). See Daniels (2005) for a novel

quantitative approach.

6. Tesslers theoretical interest in Huntingtons thesis is more limited than our own, and his

already-published analyses necessarily rely on older data from fewer Arab publics, but we are much

indebted to his work in general and to his distinction between personal and political identification with Islam in particular. Per his distinction and implicit recommendation, we here focus on the

latter.

7. Nor, to reiterate, is our paper meant to be a definitive commentary on the clash thesis as

Huntington originally proposed it. In ignoring all but one of at least fifty-six directed inter-civilizational

dyads that Huntington (1993, 1996) thinks relevant to international politics, we are hardly testing

whether he has correctly divined the emerging world order. That claim, as far as we are concerned,

has been decisively rejected by the quantitative IR scholars mentioned above.

8. Although more recently, including in the interview quoted in the epigraph, Huntington himself has underlined his original remarks about subdivisions within Islam (e.g., between Arabic, Malay,

and Turkic traditions). See Pew, 2006c and Huntington, 1993, 1996.

9. For a clearer articulation of a view that all of Muslim civilization is at odds with the West, see

Hirsi Ali, 2006 and Hitchens, 2006.

10. Preliminary t-tests nevertheless suggest that Christian Arabs are not significantly different from

Muslim Arabs in their attitudes toward Western countries.

11. Although authors writing in a global context are often quick to attribute malefemale differences in out-group hostility to differential socialization (Caprioli, 2005; Melander, 2005), and although

several of the scholars mentioned above argue that the joint presence of Arabness and maleness is

particularly significant (see Rizzo et al., 2007), many Middle East specialists are (we think rightly) as wary

of cultural arguments as they are of biological ones. In any event, it seems to us that we can leave

the question of the sources of putative sex/gender differences in hostility to the West unanswered until

determining whether or not such differences obtain.

12. The Jordanian and Egyptian batteries of Pews 2005 survey, for example, asked about attitudes toward the U.S., Germany, and France, but, unfortunately, did not address respondents identity

orientations (see also Pew, 2006a). The Revisiting the Arab Street study by the Center for Strategic

Studies (CSS) at the University of Jordan (2005) samples five Arab publics in regard to their attitudes

about the U.S., Great Britain, and France, but this coverage is less comprehensive than that of the Arab

Values Survey, as is its operationalization of attitudes related to civilization consciousness (CSS, 2005, pp.

6466). A partial 2005 replication of the 2002 Arab Values Survey by Zogby itself operationalizes civilization consciousness less comprehensively than the 2002 survey and, more important, queries respondents

about only one Western object country (the U.S.) rather than five.

13. The survey was carried out by Zogby International and the Arab Thought Foundation.

Frequency tables are published in Zogby (2002) and the full dataset is available for purchase. It is not

part of the World Values Survey, which was also conducted in 2002 in four Arab countries (but does not

contain data on attitudes toward Western object countries). For discussions of the WVS in regards to

Muslim and Middle Eastern publics, see Moaddel (2007).

14. Following Furia and Lucas (2006), we omit Zogbys sample of Israeli Arabs for various theoretical reasons: 1.) because we test their alternative explanation of the determinants of Arab opinion via

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

204

P. A. Furia and R. E. Lucas

an independent variable on attitudes toward Palestine and 2.) because we include a control variable on

whether or not respondents are citizens of the states in which they reside that we suspect has a different

interpretation for Arabs in Israel than it does for other respondents.

15. Although what is sometimes referred to as Huntingtons kin-countries hypothesis is of less

interest to post-9/11 commentators, a previous version of this paper presented results on Arab-Muslim

attitudes toward the Muslim countries asked about in the survey as well (i.e., Iran, Pakistan, and

Turkey). Although deleted for reasons of space, these analyses are available from the authors, as are

analyses of non-Western, non-Muslim countries (China, India, Japan, and Russia).

16. Rather than using Zogbys own (often quite substantial) weighting variables to adjust the

socio-demographics of the sample to national and regional norms, we analyze unweighted data and

introduce demographic controls directly into our analysis. We have also conducted subject country specific replications of each of our models (available from the authors) and confirmed that there are a.) few

significant differences between each of these country-specific samples and the pooled sample and b.) no

significant differences between the Egypt-specific results and the pooled sample. Given these various

checks, therefore, we do believe that our analysis is substantially representative of the views of Arab

Muslims in the Middle East.

17. Specifically, respondents were asked to answer the following question: I will read you a list

of countries. Please tell me if your overall impression of each is either: very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable or very unfavorable, or if you are not familiar enough to form a judgment.

18. On the debate between measuring predominant (i.e., primary) identifications vs. levels of

identification, see Davis and Davenports (1997) critique of Inglehart (1997). As for preferring to analyze

Muslim Arabs identity consciousness as expressed to Arabs on the one hand and to Americans on the

other, the presumption that an analysis of foreign relations should focus on foreign expressions of identity-consciousness must be balanced against the facts that a.) the questions about expressions of identifications to fellow Arabs precede these on the survey and b.) Zogby International in 2005 replaced asking

about expressions of identity-consciousness to foreign Americans with a question about expressions to

foreign Europeans.

19. The final question, as exemplary of the scope and wording of the four, reads Now, suppose

you are talking with someone from the United States. Using the same scale of one to five, with one

being not at all important and five being very important, and the same list [family, the city or region

where you live, the country in which you live, your religion, being Arab, the social background of your

family], please tell me how important each of the following is in defining who you are to that American.

For additional information on question wording, see Zogby, 2002, chap. 6.

20. Even were such questions available, the intra-national income variation items typical of the

World Values Survey would be problematic to use in our pooled analysis given the disparities of wealth

between Arab states such as Egypt and Kuwait.

21. The original question includes a third category for non-Arab noncitizens of a particular subject

country, but our limitation of the present analysis to Arab Muslims renders this category an empty cell.

22. If not attributable to random noise, these patterns may also be an artifact of the systematically

low regard in which noncitizen Arab residents hold Canada and Germany. See here the coefficients for

the dichotomous citizenship variable.

REFERENCES

Ajami, Fouad (2006). The Foreigners Gift: The Americans, the Arabs, and the Iraqis

in Iraq, New York: Free Press.

Caprioli, M. (2005). Primed for Violence: The Role of Gender Inequality in Predicting Internal Conflict. International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 49, pp. 161178.

Center for Strategic Studies, University of Jordan (2005). Revisiting the Arab Street:

Research From Within, Amman: Center for Strategic Studies.

Chiozza, Giacomo (2002). Is There a Clash of Civilizations? Evidence from Patterns

of International Conflict Involvement, 194697. Journal of Peace Research,

Vol. 39, No. 6, pp. 711734.

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

205

Chomsky, Noam (2001). 911, New York: Seven Stories Press.

Davis, Darren and Christian Davenport (1999). Assessing the Validity of the

Postmaterialism Index. American Political Science Review, Vol. 93, No. 3, pp.

649664.

Daniels, Joseph P. (2005). Religious Preferences and Individual International-Policy

Preferences in the United States, International Interactions, Vol. 31, No. 4,

pp. 273301.

Downs, Anthony (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy, New York: Harper.

Espositio, John and Dalia Mogahed (2008). Who Speaks for Islam?, Washington DC:

Gallup Press.

Farrington, David (1999). Predictors, Causes, and Correlates of Male Youth

Violence. Crime and Justice, Vol. 24, pp. 421475.

Fox, Jonathan (2001). Two Civilizations and Ethnic Conflict: Islam and the West.

Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 459472.

Friedman, Thomas (1999). The Lexus and the Olive Tree, New York: Anchor Press.

Fukuyama, Francis (1998). Women and the Evolution of World Politics. Foreign

Affairs, Vol. 77, No. 5, pp. 2441.

Furia, Peter and Russell Lucas (2006). Determinants of Arab Public Opinion on Foreign Relations. International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 585605.

Gurr, Ted Robert (1970). Why Men Rebel, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hafez, Mohammed (2004). Why Muslims Rebel, Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Harris, Sam (2005). The End of Faith, New York: WW Norton & Company.

Henderson, Errol (1997). Culture or Contiguity: Ethnic Conflict, the Similarity of

States, and the Onset of War, 18201989. The Journal of Conflict Resolution,

Vol. 41, No. 5, pp. 649668.

Hirsi Ali, Ayan (2006). The Caged Virgin: An Emancipation Proclamation for

Women and Islam, New York: The Free Press.

Hitchens, Chirstopher (2006). The Caged Virgin: Hollands Shameful Treatment of

Ayaan Hirsi Ali. Slate, May 8, 2006. http://www.slate.com/id/2141276/

Holsi, Ole R. (1996). Public Opinion and American Foreign Policy, Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Press.

Huntington, Samuel (1993). The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs, Vol. 72,

No. 3, pp. 2250.

Huntington, Samuel (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World

Order, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Huntington, Samuel (2000). Try Again: A Reply to Russett, Oneal, and Cox.

Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 609610.

Ibrahim, Saad Eddin (1980). Anatomy of Egypts Militant Islamic Groups:

Methodological Note and Preliminary Findings. International Journal of

Middle East Studies, Vol. 12, pp. 423453.

Inglehart, Ronald (1997). Modernization and Postmodernization, Princeton:

Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald and Pippa Norris (2003). The True Clash of Civilizations.

Foreign Policy, Vol. 135, MarchApril, pp. 6270.

Kaplan, Robert (1994). The Coming Anarchy. Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 273, pp. 4476.

Lipset, Seymour Martin (1968). Revolution and Counterrevolution, New York: Basic

Books.

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

206

P. A. Furia and R. E. Lucas

Macdonald, Ian (2006). A Clash of Civilizations: There Has Been No Peace Since

the Sept. 11 Attacks That Launched the War on Terror. The Gazette

(Montreal), September 11, 2006, p. A21.

Manji, Irshad (2005). The Trouble with Islam Today, New York: St. Martins Press.

Mearsheimer, John (1990). Back to the Future. International Security, Vol. 15, pp. 556.

Melander, Erik (2005). Gender Equality and Intrastate Armed Conflict. International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 49, pp. 695714.

Moaddel, Mansoor, ed. (2007). Values and Perceptions of the Islamic and Middle

Eastern Publics, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Morganthau, Hans (1954). Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and

Peace, 2nd edition. New York: Alfred A Knopf.

Norris, Pippa (2000). Global Governance and Cosmopolitan Citizens, in Joseph

Nye and John Donahue, eds., Governance in a Globalizing World,

Washington: Brookings Press.

Page, Bernard and Robert Shapiro (1992). The Rational Public : Fifty Years of Trends

in Americans Policy Preferences, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pape, Robert A. (2003). The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism. American

Political Science Review, Vol. 97, No. 3, pp. 343361.

Pew Global Attitudes Project (2001). America Admired, Yet Its New Vulnerability

Seen As Good Thing, Say Opinion Leaders, Washington, D.C.: Pew Research

Center. http://pewglobal.org/reports/display.php?ReportID=145

Pew Global Attitudes Project (2002). What the World Thinks in 2002, Washington, D.C.:

Pew Research Center. http://pewglobal.org/reports/display.php?ReportID =165

Pew Global Attitudes Project (2005). Global Opinion: The Spread of AntiAmericanism. In Trends 2005, Pew Research Center. Washington, D.C.: Pew

Research Center, pp. 105119.

Pew Global Attitudes Project (2006a). Americas Image Slips, But Allies Share U.S.

Concerns Over Iran, Hamas, Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. http://

pewglobal.org/reports/display.php?ReportID=252

Pew Global Attitudes Project (2006b). The US Publics Pro-Israel History,

Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. http://pewglobal.org/commentary/

display.php?AnalysisID=1008

Pew Global Attitudes Project (2006c). Five Years After 9/11: The Clash of

Civilizations Revisited. http://pewforum.org/events/index.php?EventID=125

Rizzo, H., A. H. Abdel-Latif, and K. Meyer (2007). The Relationship Between

Gender Equality and Democracy: A Comparison of Arab Versus Non-Arab

Muslim Socieities. Sociology, Vol. 41, No. 6, pp. 11511170.

Roeder, Philip (2003). Clash of Civilizations and Escalation of Domestic Ethnopolitical Conflicts. Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 36, No. 5, pp. 509540.

Russett, Bruce and John Oneal (2001). Triangulating Peace, New York: Norton.

Russett, Bruce, John Oneal, and Michaelene Cox (2000). Clash of civilizations, or

Realism and Liberalism Dj vu? Some Evidence. Journal of Peace Research,

Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 583608.

Sardar, Ziauddin and Merryl Wyn Davies (2002). Why Do People Hate America?

New York: Disinformation.

Skocpol, Theda (1979). States and Social Revolutions, Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

Downloaded By: [EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution] At: 15:49 24 June 2008

Arab Anti-Western Attitudes

207

Telhami, Shibley (2002). The Stakes: America and the Middle East, Boulder: Westview Press.

Tessler, Mark (2002). Do Islamic Orientations Influence Attitudes Toward

Democracy in the Arab World? Evidence from Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and

Algeria. World Values Survey Research Papers. Paper 200226. http://www.

worldvaluessurvey.org/Upload/5_TessIslamDem_2.pdf

Tessler, Mark (2003). Arab and Muslim Political Attitudes: Stereotypes and

Evidence from Survey Research. International Studies Perspectives, Vol. 4,

pp. 175181.

Tessler, Mark and Jodi Nachtwey (1998). Islam and Attitudes Toward International

Conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 42, No. 5, pp. 619636.

Tessler, Mark, Judi Nachtwey, and Audra Grant (1999). Further Tests of the

Women and Peace Hypothesis: Evidence from Cross-National Survey Research

in the Middle East. International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 43, pp. 519531.

Tusicisny, Andrej (2004). Civilizational Conflicts: More Frequent, Longer, and

Bloodier? Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 41, No. 4, pp. 485498.

Urdal, Henrik (2006). A Clash of Generations? Youth Bulges and Political

Violence. International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 50, pp. 607629.

Waltz, Kenneth (1959). Man, the State and War, New York: Columbia University

Press.

Waltz, Kenneth (1979). Theory of International Politics, New York: McGraw-Hill/

Wright, Robert (2002). A Real War on Terrorism. Slate, September 3, 2002 (on-line

resource). http://www.slate.com/id/2070210/

Zakaria, Fareed (2003). The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and

Abroad, New York: WW Norton & Company.

Zogby, James (2002). What Arabs Think: Values Beliefs and Concerns, Utica NY:

Zogby International.

Zogby International (2002b). The Ten Nation Impressions of America Poll, Utica,

NY: Zogby International.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The King Is in the Field: Essays in Modern Jewish Political ThoughtD'EverandThe King Is in the Field: Essays in Modern Jewish Political ThoughtPas encore d'évaluation

- As The World Powers Head To War They Imply That Your Faith Is Part of Their Policies. Anybody Who Disagrees Will Be Associated With Revolution or ExtremismDocument38 pagesAs The World Powers Head To War They Imply That Your Faith Is Part of Their Policies. Anybody Who Disagrees Will Be Associated With Revolution or Extremismmanufactured-agePas encore d'évaluation

- State Vs Non-State Terrorism - A Critical ApproachDocument9 pagesState Vs Non-State Terrorism - A Critical ApproachSLY ROJANPas encore d'évaluation

- Samuel Huntington Clash of Civilizations ThesisDocument6 pagesSamuel Huntington Clash of Civilizations Thesisxmlzofhig100% (2)

- Islam's Bloody InnardsDocument17 pagesIslam's Bloody InnardsChristian Lomsdalen MarsteinPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Science PHD ThesisDocument5 pagesPolitical Science PHD Thesismelaniesmithreno100% (1)

- Research Paper On Terrorism in The United StatesDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Terrorism in The United Stateszxqefjvhf100% (1)

- Religious Knives: Historical and Psychological Dimensions of International TerrorismD'EverandReligious Knives: Historical and Psychological Dimensions of International TerrorismPas encore d'évaluation

- Master ThesisDocument90 pagesMaster Thesistalal77Pas encore d'évaluation

- Master ThesisDocument90 pagesMaster Thesistalal77Pas encore d'évaluation

- The End of the West?: Crisis and Change in the Atlantic OrderD'EverandThe End of the West?: Crisis and Change in the Atlantic OrderPas encore d'évaluation

- Clash of CivilisationDocument13 pagesClash of CivilisationMaryam SiddiquiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dissertation Questions On IslamophobiaDocument7 pagesDissertation Questions On IslamophobiaCustomPapersCleveland100% (1)

- Krueger Maleckova 2002Document45 pagesKrueger Maleckova 2002Usman Abdur RehmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Said's War On The IntellectualsDocument5 pagesSaid's War On The IntellectualsRochelle TermanPas encore d'évaluation

- "Heroes" and "Villains" of World History Across CulturesDocument21 pages"Heroes" and "Villains" of World History Across CultureschanvierPas encore d'évaluation

- Abozaid 2018 - Clash of Civilizations at 25-View From The Arab WorldDocument25 pagesAbozaid 2018 - Clash of Civilizations at 25-View From The Arab WorldThao Nguyen Nguyen TranPas encore d'évaluation

- God Gap Humanitarian Law FINALDocument62 pagesGod Gap Humanitarian Law FINALEzaz UllahPas encore d'évaluation

- Islam and International Politics: Examining Huntington's 'Civilizational Clash' ThesisDocument12 pagesIslam and International Politics: Examining Huntington's 'Civilizational Clash' ThesisBlanka MatkovicPas encore d'évaluation

- American Nationalism and U S Foreign Policy From September 11 To The Iraq WarDocument26 pagesAmerican Nationalism and U S Foreign Policy From September 11 To The Iraq Warosegura100% (3)

- ASSIGNMENT 03 ISLAMIC STUDIES (FA21-BME-050) ProjectDocument6 pagesASSIGNMENT 03 ISLAMIC STUDIES (FA21-BME-050) ProjectmusabPas encore d'évaluation

- Escape From ViolenceDocument395 pagesEscape From Violencealexis melendezPas encore d'évaluation

- Table of ContentsDocument7 pagesTable of ContentsSyed Imtiaz AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Cultural DiplomacyDocument6 pagesCultural DiplomacyMaggie HopePas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper Topics Middle East PoliticsDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Topics Middle East Politicsafnhdcebalreda100% (1)

- Social Forces 2006 Robison 2009 26Document18 pagesSocial Forces 2006 Robison 2009 26Agne CepinskytePas encore d'évaluation

- A Political Discourse Analysis of Islamophobia Though The Novel Home BoyDocument18 pagesA Political Discourse Analysis of Islamophobia Though The Novel Home Boysabaazaidi2845Pas encore d'évaluation

- Demos Briefing Paper Far Right Extremism 2017Document11 pagesDemos Briefing Paper Far Right Extremism 2017ddufourtPas encore d'évaluation

- Women and the White House: Gender, Popular Culture, and Presidential PoliticsD'EverandWomen and the White House: Gender, Popular Culture, and Presidential PoliticsPas encore d'évaluation

- Islam, Judaism, and The Political Role of The Religions in The Middle East PDFDocument216 pagesIslam, Judaism, and The Political Role of The Religions in The Middle East PDFPeter100% (1)

- Bilbo Baggins 911Document99 pagesBilbo Baggins 911gensgeorge4328Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mark Juergensmeyer Is Religion The ProblemDocument11 pagesMark Juergensmeyer Is Religion The ProblemMaya GeorgPas encore d'évaluation

- Is A Clash Between Islam and The West Inevitable?: June 2016Document24 pagesIs A Clash Between Islam and The West Inevitable?: June 2016ruhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Media Coverage of Muslims - Introduction and OverviewDocument18 pagesMedia Coverage of Muslims - Introduction and Overviewsihem.merghoubPas encore d'évaluation

- How Jewish Was StrausDocument40 pagesHow Jewish Was StrausAbbass BrahamPas encore d'évaluation

- 1904 - CA1 Assignment - Political ScienceDocument6 pages1904 - CA1 Assignment - Political ScienceLakshya SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reconciliation Through Communication in Intercultural EncountersDocument11 pagesReconciliation Through Communication in Intercultural EncountersΔημήτρης ΑγουρίδαςPas encore d'évaluation

- After Secularism Rethinking Religion in PDFDocument30 pagesAfter Secularism Rethinking Religion in PDFNaeem RahmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Dreaming As A Critical Discourse of National Belonging: China Dream, American Dream and World DreamDocument41 pagesDreaming As A Critical Discourse of National Belonging: China Dream, American Dream and World DreamCherub GundalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Political StudiesDocument6 pagesComparative Political StudiesSunil Mike VictorPas encore d'évaluation

- Rowe - The Cultural Politics of The New American StudiesDocument236 pagesRowe - The Cultural Politics of The New American Studiesmplateau100% (1)

- Karawan, I., "Middle East Studies After 9:11 - Time For An Audit" - Literature Review - Topics in International PoliticsDocument7 pagesKarawan, I., "Middle East Studies After 9:11 - Time For An Audit" - Literature Review - Topics in International PoliticsJoaPas encore d'évaluation

- Islam Through Western EyesDocument4 pagesIslam Through Western EyesAli AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- FOX, Jonathan. Religion As An Overlooked Element of International RelationsDocument21 pagesFOX, Jonathan. Religion As An Overlooked Element of International Relationsqbv45286Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sociology of TerrorismDocument17 pagesSociology of TerrorismNicolas VallejoPas encore d'évaluation

- Belonging without Othering: How We Save Ourselves and the WorldD'EverandBelonging without Othering: How We Save Ourselves and the WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Race Matters in International RelationsDocument7 pagesWhy Race Matters in International RelationsAdnan AfzalPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative PoliticsDocument6 pagesComparative PoliticsWOLf WAZIR GAMINGPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Statement On Religion and PoliticsDocument4 pagesThesis Statement On Religion and PoliticsJoshua Gorinson100% (2)

- Populism Ontological Security and Gendered NationalismDocument19 pagesPopulism Ontological Security and Gendered Nationalismmikey litwackPas encore d'évaluation

- Habermas Religion in The Public Sphere PDFDocument22 pagesHabermas Religion in The Public Sphere PDFmarkuskellerii1875Pas encore d'évaluation

- Audit English 2011Document20 pagesAudit English 2011Cfca AntisemitismPas encore d'évaluation

- Arab Spring and Political ScienceDocument25 pagesArab Spring and Political ScienceMohamed SoffarPas encore d'évaluation

- Hizb Ut-Tahrir by Zeyno BaranDocument144 pagesHizb Ut-Tahrir by Zeyno BaranTarek Fatah100% (1)

- Mahmood Mamdani Lse Lecture The Politics of Culture TalkDocument22 pagesMahmood Mamdani Lse Lecture The Politics of Culture TalkalkanhilalPas encore d'évaluation

- Soldier of Fortune (1993'02) 7PDocument7 pagesSoldier of Fortune (1993'02) 7PContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Serbias Sandzak Under MilosevicDocument22 pagesSerbias Sandzak Under MilosevicContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Yugo Nostalgia Cultural Memory and Media in The Former YugoslaviaDocument19 pagesYugo Nostalgia Cultural Memory and Media in The Former YugoslaviaGeno GoletianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychopaths and Blame The Argument From ContentDocument18 pagesPsychopaths and Blame The Argument From ContentcorinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Who Is Playing Russian Roulette in SlovakiaDocument150 pagesWho Is Playing Russian Roulette in SlovakiaContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Amor Masovic Testimony To US CongressDocument5 pagesAmor Masovic Testimony To US CongressContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Community Education: To Reclaim and Transform What Has Been Made InvisibleDocument18 pagesCommunity Education: To Reclaim and Transform What Has Been Made InvisibleContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Reconstructing The Meaning of Being Montenegrin - by Jelena DzankicDocument25 pagesReconstructing The Meaning of Being Montenegrin - by Jelena DzankicContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Muslims in America Congressional Report April 30Document32 pagesMuslims in America Congressional Report April 30Contributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook of COVID19 Prevention and Treatment PDFDocument68 pagesHandbook of COVID19 Prevention and Treatment PDFZaw Min TunPas encore d'évaluation

- African American Muslims Contribution For The Civil Rights MovementDocument1 pageAfrican American Muslims Contribution For The Civil Rights MovementContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Why We Care and Why We ForgiveDocument28 pagesWhy We Care and Why We ForgiveContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Black Muslims in AmericaDocument296 pagesBlack Muslims in AmericaContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Chetniks Encyclopedia of HolocaustDocument9 pagesChetniks Encyclopedia of HolocaustContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Glasnik Islamske Zajednice 2010Document6 pagesGlasnik Islamske Zajednice 2010Contributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

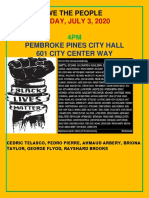

- Pembroke Pines City Hall 601 City Center Way: FRIDAY, JULY 3, 2020Document2 pagesPembroke Pines City Hall 601 City Center Way: FRIDAY, JULY 3, 2020Contributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

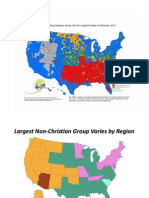

- Tracking 2020census ResponseRate 04142020Document1 pageTracking 2020census ResponseRate 04142020Contributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook of COVID19 Prevention and Treatment PDFDocument68 pagesHandbook of COVID19 Prevention and Treatment PDFZaw Min TunPas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook of COVID19 Prevention and Treatment PDFDocument68 pagesHandbook of COVID19 Prevention and Treatment PDFZaw Min TunPas encore d'évaluation

- Risk of Being Killed by Police Use of Force in The United States by Age, Race-Ethnicity, and SexDocument9 pagesRisk of Being Killed by Police Use of Force in The United States by Age, Race-Ethnicity, and SexContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- This Is Our Little HajjDocument15 pagesThis Is Our Little HajjContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Mladi Muslimani Interview Alija Izetbegovic TrhuljDocument8 pagesMladi Muslimani Interview Alija Izetbegovic TrhuljContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- Excratct: To The Serbs An Episle From Moscow ExtractDocument2 pagesExcratct: To The Serbs An Episle From Moscow ExtractContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation

- The Green New Deal Via Ms. OCASIO-CORTEZ @AOCDocument14 pagesThe Green New Deal Via Ms. OCASIO-CORTEZ @AOCJeffrey Ventre MD DCPas encore d'évaluation

- Latinos and The Transformation of American ReligionDocument12 pagesLatinos and The Transformation of American ReligionContributor BalkanchroniclePas encore d'évaluation