Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Declaration of The Rights of Man and of The Citizen

Transféré par

Tess LegaspiTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Declaration of The Rights of Man and of The Citizen

Transféré par

Tess LegaspiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

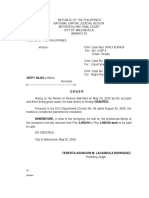

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

French Declaration des Droits de lHomme et du Citoyen, one of

the basic charters of human liberties, containing the principles

that inspired the French Revolution. Its 17 articles, adopted

between August 20 and August 26, 1789, by Frances National

Assembly, served as the preamble to the Constitution of 1791.

Similar documents served as the preamble to the Constitution of

1793 (retitled simply Declaration of the Rights of Man) and to

the Constitution of 1795 (retitled Declaration of the Rights and

Duties of Man and the Citizen).

The basic principle of the Declaration was that all men are born

and remain free and equal in rights (Article 1), which were

specified as the rights of liberty, private property, the

inviolability of the person, and resistance to oppression (Article

2). All citizens were equal before the law and were to have the

right to participate in legislation directly or indirectly (Article 6);

no one was to be arrested without a judicial order (Article 7).

Freedom of religion (Article 10) and freedom of speech (Article

11) were safeguarded within the bounds of public order and

law. The document reflects the interests of the elites who

wrote it: property was given the status of an inviolable right,

which could be taken by the state only if an indemnity were

given (Article 17); offices and position were opened to all

citizens (Article 6).

Approved by the National Assembly of France, August 26,

1789

The representatives of the French people, organized as a

National Assembly, believing that the ignorance, neglect, or

contempt of the rights of man are the sole cause of public

calamities and of the corruption of governments, have

determined to set forth in a solemn declaration the natural,

unalienable, and sacred rights of man, in order that this

declaration, being constantly before all the members of the

Social body, shall remind them continually of their rights and

duties; in order that the acts of the legislative power, as well as

those of the executive power, may be compared at any moment

with the objects and purposes of all political institutions and

may thus be more respected, and, lastly, in order that the

grievances of the citizens, based hereafter upon simple and

incontestable principles, shall tend to the maintenance of the

constitution and redound to the happiness of all. Therefore the

National Assembly recognizes and proclaims, in the presence

and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following

rights of man and of the citizen:

Articles:

1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social

distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

2. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the

natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are

liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

3. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the

nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which

does not proceed directly from the nation.

4. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which

injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of

each man has no limits except those which assure to the other

members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These

limits can only be determined by law.

5. Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to society.

Nothing may be prevented which is not forbidden by law, and no

one may be forced to do anything not provided for by law.

6. Law is the expression of the general will. Every citizen has a

right to participate personally, or through his representative, in

its foundation. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or

punishes. All citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are

equally eligible to all dignities and to all public positions and

occupations, according to their abilities, and without distinction

except that of their virtues and talents.

7. No person shall be accused, arrested, or imprisoned except

in the cases and according to the forms prescribed by law. Any

one soliciting, transmitting, executing, or causing to be

executed, any arbitrary order, shall be punished. But any citizen

summoned or arrested in virtue of the law shall submit without

delay, as resistance constitutes an offense.

8. The law shall provide for such punishments only as are

strictly and obviously necessary, and no one shall suffer

punishment except it be legally inflicted in virtue of a law

passed and promulgated before the commission of the offense.

9. As all persons are held innocent until they shall have been

declared guilty, if arrest shall be deemed indispensable, all

harshness not essential to the securing of the prisoner's person

shall be severely repressed by law.

10. No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions,

including his religious views, provided their manifestation does

not disturb the public order established by law.

11. The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the

most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may,

accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom, but shall be

responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined

by law.

12. The security of the rights of man and of the citizen requires

public military forces. These forces are, therefore, established

for the good of all and not for the personal advantage of those

to whom they shall be intrusted.

13. A common contribution is essential for the maintenance of

the public forces and for the cost of administration. This should

be equitably distributed among all the citizens in proportion to

their means.

14. All the citizens have a right to decide, either personally or

by their representatives, as to the necessity of the public

contribution; to grant this freely; to know to what uses it is put;

and to fix the proportion, the mode of assessment and of

collection and the duration of the taxes.

15. Society has the right to require of every public agent an

account of his administration.

16. A society in which the observance of the law is not assured,

nor the separation of powers defined, has no constitution at all.

17. Since property is an inviolable and sacred right, no one shall

be deprived thereof except where public necessity, legally

determined, shall clearly demand it, and then only on condition

that the owner shall have been previously and equitably

indemnified.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- IPCRDocument1 pageIPCRTess Legaspi0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- 2013-10-26 Memorandum Right To Travel Vol 1Document33 pages2013-10-26 Memorandum Right To Travel Vol 1rifishman1100% (10)

- Special Proceeding Reviewer (Regalado)Document36 pagesSpecial Proceeding Reviewer (Regalado)Faith Laperal91% (11)

- The Business TrustDocument17 pagesThe Business TrustdbircS4264100% (5)

- Us History Eoc Review Guide 1Document47 pagesUs History Eoc Review Guide 1api-334758672Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Passport Affidavit of LossDocument2 pagesPhilippine Passport Affidavit of LossTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Pio Barretto Sons, Inc. vs. Compania Maritima, 62 SCRA 167Document100 pagesPio Barretto Sons, Inc. vs. Compania Maritima, 62 SCRA 167Tess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of LossDocument1 pageAffidavit of LossTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Talk GuidelinesDocument4 pagesBook Talk GuidelinesTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative Circular Ej Vej SeminarDocument2 pagesAdministrative Circular Ej Vej SeminarTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Law II SyllabusDocument14 pagesConstitutional Law II SyllabusTess Legaspi0% (1)

- SPMS Annex A Court PerformanceDocument1 pageSPMS Annex A Court PerformanceTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Torts and DamagesDocument32 pagesTorts and DamagesTess Legaspi100% (3)

- Metropolitan Trial Court: CC: Occ/accDocument1 pageMetropolitan Trial Court: CC: Occ/accTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative LawDocument8 pagesAdministrative LawTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- 2juris in InsuranceDocument3 pages2juris in InsuranceTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Health and Welfare New MemberDocument3 pagesHealth and Welfare New MemberTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2Document7 pagesModule 2Tess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviewer SuccessionDocument34 pagesReviewer SuccessionTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1Document10 pagesModule 1Tess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 3Document8 pagesModule 3Tess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Act No 496Document13 pagesAct No 496Tess Legaspi100% (1)

- Local Government Code Book II provisionsDocument81 pagesLocal Government Code Book II provisionsTess Legaspi100% (1)

- Transportation Law CasesDocument133 pagesTransportation Law CasesTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- RA8485 Animal Welfare Act (Carabao Slaughter)Document2 pagesRA8485 Animal Welfare Act (Carabao Slaughter)Jazreth Gaile100% (1)

- RA 9775 Anti Child Pornography Act of 2009Document14 pagesRA 9775 Anti Child Pornography Act of 2009Uc ItlawPas encore d'évaluation

- General Principles of TaxationDocument50 pagesGeneral Principles of TaxationKJ Vecino BontuyanPas encore d'évaluation

- PicturesDocument12 pagesPicturesTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit No RelativeDocument1 pageAffidavit No RelativeTess Legaspi100% (1)

- Diplomatic IntercourseDocument8 pagesDiplomatic IntercourseTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Lincoln, the Man of the PeopleDocument3 pagesLincoln, the Man of the PeopleTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- New Law On Child Pornography in CyberspaceDocument4 pagesNew Law On Child Pornography in CyberspaceTess LegaspiPas encore d'évaluation

- Essential Question and Enduring Understanding TutorialDocument28 pagesEssential Question and Enduring Understanding TutorialAureliano BuendiaPas encore d'évaluation

- THE Economics OF Justice: Richard A. PosnerDocument215 pagesTHE Economics OF Justice: Richard A. PosnerSebastian Faúndez Madariaga100% (1)

- Philippine Government and Constitutioncourse GuideDocument9 pagesPhilippine Government and Constitutioncourse GuideMarilie Joy Aguipo-AlfaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of early international air lawDocument19 pagesDevelopment of early international air lawEnis LatićPas encore d'évaluation

- PRC - Letxs ReviewDocument21 pagesPRC - Letxs ReviewNorman PromentilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Ethics Concepts & Cases: Manuel G. VelasquezDocument181 pagesBusiness Ethics Concepts & Cases: Manuel G. VelasquezPutera Firdaus100% (1)

- Legal and Ethical Issues of Human Cloning in the PhilippinesDocument12 pagesLegal and Ethical Issues of Human Cloning in the PhilippinesLeah Marshall100% (1)

- Chapter 14 EthicDocument36 pagesChapter 14 Ethicike4546100% (1)

- Chapter 1Document17 pagesChapter 1isaiah8195Pas encore d'évaluation

- Civ Eng TGG6Document110 pagesCiv Eng TGG6kemimePas encore d'évaluation

- West Virginia Bd. of Ed. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943)Document34 pagesWest Virginia Bd. of Ed. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- HistoryClass9 PDFDocument189 pagesHistoryClass9 PDFShruPas encore d'évaluation

- Czech Civil Code in EnglishDocument416 pagesCzech Civil Code in EnglishOctav CazacPas encore d'évaluation

- Mening of Local Self GovernmentDocument89 pagesMening of Local Self GovernmentNijam Shukla50% (4)

- Report1 Mesne ProfitsDocument17 pagesReport1 Mesne ProfitsKapil SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pol Sci 100 - B Mariñas 18Document2 pagesPol Sci 100 - B Mariñas 18Gianne Alexandria MariñasPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Analysis On JurisprudenceDocument19 pagesCase Analysis On JurisprudencePushpendra BadgotiPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 Social Impq History Ch1 5Document4 pages9 Social Impq History Ch1 5Bhas Kar-waiPas encore d'évaluation

- DemocracyDocument9 pagesDemocracyGabriel PopescuPas encore d'évaluation

- PT&T vs. NLRC 272 SCRA 596Document2 pagesPT&T vs. NLRC 272 SCRA 596Ge Ann Michelle BauzonPas encore d'évaluation

- Youth Justice in The United Kingdom CarrabineDocument13 pagesYouth Justice in The United Kingdom CarrabineMiguel VelázquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Part 2: Contracts: A) Contrary To LawDocument8 pagesPart 2: Contracts: A) Contrary To LawWest Gomez JucoPas encore d'évaluation

- Regalian DoctrineDocument66 pagesRegalian DoctrineRico UrbanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Singapore Husoc ProceedingsDocument54 pagesSingapore Husoc ProceedingsGlobal Research and Development ServicesPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Find Out Who You AreDocument18 pagesHow To Find Out Who You AreJulian Williams©™100% (2)

- The UDHRDocument35 pagesThe UDHRCha100% (1)