Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Rough and Tumble Play

Transféré par

ryn8011Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Rough and Tumble Play

Transféré par

ryn8011Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

This article was downloaded by: [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris]

On: 25 November 2014, At: 02:07

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Early Child Development and Care

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gecd20

Preschool teachers' perceptions of

rough and tumble play vs. aggression in

preschool-aged boys

a

Cynthia F. DiCarlo , Jennifer Baumgartner , Carrie Ota &

Charlene Jenkins

School of Education, Louisiana State University, 123B Peabody

Hall, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA

b

Department of Child & Family Studies, Weber State University,

1301 University Circle, Ogden, UT 84088, USA

c

The Infant/Toddler Developmental Center, n/a, 4951 Mewell

Street, Zachary, LA 70791, USA

Published online: 29 Sep 2014.

To cite this article: Cynthia F. DiCarlo, Jennifer Baumgartner, Carrie Ota & Charlene Jenkins

(2014): Preschool teachers' perceptions of rough and tumble play vs. aggression in preschool-aged

boys, Early Child Development and Care, DOI: 10.1080/03004430.2014.957692

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.957692

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or

howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising

out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

Early Child Development and Care, 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.957692

Preschool teachers perceptions of rough and tumble play vs.

aggression in preschool-aged boys

Cynthia F. DiCarloa*, Jennifer Baumgartnera, Carrie Otab and Charlene Jenkinsc

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

School of Education, Louisiana State University, 123B Peabody Hall, Baton Rouge,

LA 70803, USA; bDepartment of Child & Family Studies, Weber State University, 1301

University Circle, Ogden, UT 84088, USA; cThe Infant/Toddler Developmental Center, n/a,

4951 Mewell Street, Zachary, LA 70791, USA

(Received 10 July 2014; accepted 20 August 2014)

Rough and tumble play has been found to be positive for physical, social and

cognitive development; it is often erroneously misinterpreted as aggression and

generally stopped by preschool teachers. The current study sought to examine

the relationship between teacher training and education and judgements about

aggression in children. Ninety-four preschool teachers currently working in child

care centres viewed two videotapes depicting preschool-aged boys engaged in

naturally occurring outdoor play. Participants scored the tapes for occurrence of

aggression, using their own denition. Results indicated that child care providers

with a four-year college degree in early childhood education reported less

aggressive behaviours than those without a college degree. Novice child care

providers reported higher levels of aggression than more experienced preschool

teachers; child care providers with similar education/experience were more likely

to report aggression within the same observation segment. These ndings

suggest that education may support more accurate assessments of aggressive play.

Keywords: aggression; rough and tumble play; preschool; preschool teacher

perception; preschool teacher education; preschool teacher experience

Rough and tumble play is a recognised play category during early childhood (EC) that

is necessary for healthy child development (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009). Rough and

tumble play refers to vigorous behaviours, such as wrestling, grappling, kicking, tumbling and play ghting, which appears aggressive except for the playful framework

(Flanders, Leo, Paquette, Phil, & Seguin, 2009; Jarvis, 2007; Pellegrini, 1989, 1995;

Pellegrini & Smith, 1998; Romano, Tremblay, Boulerice, & Swisher, 2005). Although

this type of play has been found to be positive for physical, social and cognitive development (Jarvis, 2007; Paquette, Carbonneau, Dubeau, Bigras, & Tremblay, 2003;

Smith, Smees, & Pellegrini, 2004), it is often erroneously misinterpreted as aggression

(Flanders et al., 2009). In fact, even in the research literature rough and tumble play has

been confused and combined with aggression when the two behaviours are dened

(Smith et al., 2004). With this confusion, it is not surprising that professionals who

work with young children might confuse normal and healthy rough and tumble play

with the more concerning and rare occurrences of aggression.

*Corresponding author. Email: cdicar2@lsu.edu

2014 Taylor & Francis

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

C.F. DiCarlo et al.

The goal of quality child care programmes is to enhance a childs social, emotional,

physical and language development and promote positive social relationships between

children and adults, which are essential to developing a childs sense of worth and

belonging (Ewing & Taylor, 2009; Hyson, Tomlinson, & Morris, 2009; Whitebook,

2003). However, the National Center for Early Development and Learning reports that

46% of kindergarten teachers identied more than half of the children in their classes

are lacking the self-regulatory skills and social competences to function productively

and learn in kindergarten (Rimm-Kaufman, Pianta, & Cox, 2000; Webster-Stratton,

Reid, & Stoolmiller, 2008). This causes concern as a lack of self-regulation and social

competence puts children at risk for academic failure, aggression, peer rejection,

school dropout, delinquency and later criminality. Child care providers interactions

with young children help the child to shape his identity; therefore, it is critical that

teachers have a knowledgeable and accurate perception of childrens development,

including the difference between normal big body play and actual physical aggression.

During EC, children are highly inuenced by adults (Webster-Stratton et al., 2008).

Child care providers are inuential in helping a child shape his identity; thus, providing

accurate feedback is important for a childs self-perception. The perception of the child

care provider could affect the childs beliefs and ideas about himself either in a positive

or negative way (Owens & Ring, 2007). There is concern that misinterpretation of

rough and tumble play could lead to incorrectly labelling children as aggressive. If a

child is so labelled and treated as such, the child may believe he is aggressive, and

then he will become what he believes (Cooley, 1902). Indeed the teacherchild relationship is linked to the childs self-perception (Colwell & Lindsey, 2003). In addition, we

know that child care providers perception of childrens behaviours can impact the

manner in which they respond to children in their care (Dobbs & Arnold, 2009;

Dobbs, Arnold, & Doctoroff, 2004; Hagekull & Hammarberg, 2004). Children who

are considered aggressive are more likely to be disliked by teachers and receive less

academic or social instruction, support and positive feedback from teachers for appropriate behaviour (Arnold, Grifth, Ortiz, & Stowe, 1998; Arnold et al., 1999; Campbell

& Ewing, 1990; Carr, Taylor, & Robinson, 1991).

Teacher education and training has long been a measure of quality (Phillips, Mekos,

Scarr, McCartney, & Abbott-Shim, 2000, others); however, recent investigations of teachers education and classroom quality have shown the effects to be mixed (Early,

Maxwell et al., 2007). There appears that teacher education and training cannot serve

as a single indicator of quality. It is clear that teachers education may be linked to childrens outcomes on certain measures (such as math, Early, Bryant et al., 2006), developmental assessments (cognitive and language development (Clarke-Stewart, Vandell,

Burchinal, OBrien, & McCartney, 2002)). Other researchers have found that caregiver

training and education do predict observed global quality of child care (Burchinal,

Cryer, Clifford, & Howes, 2002). Therefore, while there is little doubt in the literature

that teacher training is an important measure of quality of care and education (Whitebrook, 2003), there are many remaining questions regarding the relationship between

teacher education and training and the quality of care and instruction provided.

One area in critical need of additional research is the relationship between teacher

training and education and judgements about aggression in children. Rough and tumble

play is an important type of play in the socialisation of young children because it

teaches children how to appropriately manage their emotions. Through rough and

tumble play, children learn how to conform their behaviour to others and to cultural

norms (McLin, 2003; Tannock, 2008). It is important that preschool teachers have

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

Early Child Development and Care

an accurate perception of the normative rough and tumble play of the children in their

care and can distinguish normative developmental play with a more serious occurrence

of aggression. When rough and tumble play behaviour is incorrectly perceived by teachers as aggressive, the result could be a child inaccurately labelled as aggressive and

the subjection of labelled children to overly punitive responses. Over time these

responses may negatively impact childrens social competence and lead to problematic

behaviours. When rough and tumble play is perceived as aggression, preschool teachers

may intervene and stop the play (Jarvis, 2007), and deny children the opportunity to

practice these skills. For these reasons, it is imperative that caregivers have a strong

background in child development in order to make these important distinctions.

Boys are at a greater risk of being labelled as aggressive. The greatest reason for this

discrepancy is that boys are in general more active physically than girls (Finn, Johannsen, & Specker, 2002; Pellegrini & Smith, 1998). As the culture of schooling shifts to a

greater focus on academics, even within EC, skills such as self-control and communication or more valued than physical skills (Rosin, 2010). Young boys who are engaging

in running or wrestling as a part of normative development are at risk of being labelled

aggressive unless their parents, teachers and care providers have an accurate understanding of normative development. The concerns and mislabelling of aggression in

EC, particularly among boys, lead to the present work. Although a large body of

research has established a strong relationship between quality child care programmes

and the child care providers educational level (Barnett, 2003; Cunningham, Zibulsky,

& Callahan, 2009; Whitebook, 2003), little is known about how education level may

impact the child care providers perceived aggression in preschool-aged boys. In

light of the literature on the importance of child care providers education, this study

was exploratory in nature and looked at whether teachers education impacted the

amount of aggression they identied in preschool-aged boys play.

Method

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between child care providers perception of aggressive behaviour in preschool boys and the child care providers

level of education. The proposed study contributes to the body of knowledge related to

play, which has a developmental impact on young children. The data were collected

from EC teachers in two counties in a Southern State. The ethnic diversity of this particular sample was consistent with the demographics from the community.

Subjects and setting

Child care providers. The group of participants for the present study included 94 EC

child care providers employed at several community-based child care centres serving

preschool-aged children. Participating teachers were selected based on their participation in a continuing education course they were attending. Participants were

given the option of participating in the study prior to the beginning of their scheduled

training; informed consent was obtained. Demographic information that was collected on participating teachers included age, gender, ethnicity (Asian, American

indicant, African-American, Indian, Caucasian, Hispanic or other), number of years

of working in the child care eld, highest level of education (less than high school,

high school/General Equivalency Diploma (GED), Child Development Associate

(CDA) credential, associate degree in EC education, bachelors degree in EC

C.F. DiCarlo et al.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

education or graduate degree. If their degree was not in EC education, they were

asked to write in their degree). The mean age of the child care providers was 37

years (SD = 10.69, range 1863). One hundred per cent of the child care providers

were female and 71% were African-American, 22% Caucasian, 6% Latino and 1%

Asian (N = 94). Seventy-four per cent child care providers completed high school

as their highest degree (N = 70) or CDA (N = 7) and 26% had complete some level

of college education (associate degree in EC = 6, bachelors degree in EC = 6, bachelors degree non-EC = 6, masters degree in EC = 1). The participants viewed two

videos of boys playing and scored each tape on a separate data sheets, for 188

observations.

Measure

Child care providers attending training sessions within their community were asked to

score each of the two videotapes at the beginning of their training session. Each 10minute video included footage of preschool-aged boys engaging in typical outdoor

play at a child care centre. The participants were told to view each video and score

according to their own denition of appropriate play or aggression. Level of education was of interest to the present study. Specically, authors hypothesise that teachers denitions of aggression may vary based on their education level. Caregivers

use their self-identied denition/construct of aggression to make judgements about

child behaviour in their professional practice daily. Therefore, no formal denition

was used in this study. This should not be perceived as a confound, but central to

the primary research question. A code of non-occurrence was provided to help participants keep their place on the data sheet (see description above). A key box was

located in the upper right hand corner of the data sheet with the letters P, M, A,

which represented peer (included adults), material (blocks, balls, bikes etc.) and

alone. As the participants viewed the video and decided on the type of play, they

also indicated if the child played with peers, materials or alone by using a slash

mark to represent their responses.

Videos

Videos of the participants were recorded at their child care centre by the last author.

Both children were four-year-old, African-American males who attended preschool.

Teachers were given no instruction on their behaviour with the target child while

each video was being recorded. Target children were identied in each video by

the colour of the shirt they were wearing. Each 10-minute video was divided into

30 20-second intervals, which corresponded to the numbering/lettering on the data

sheet. A green caution light appeared on the videotape to indicate the beginning

of each 20-second interval and a stop sign appeared when that interval ended. In

addition, a 5-second pause was added to give participants time to mark their

responses before the next interval began. In minute (1), the segment on the videotape

read 1A (:00), 1B (:20) and 1C (:40). Participants scored their perception of

aggression continuously during the 10-minute video by noting if aggression was

present or not present (dichotomous) during each 20-second interval. Participants

worked independently and were told not to discuss their responses while viewing

the tapes.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

Early Child Development and Care

Master codes

Master codes for the videos were developed by the rst and last authors (see Justice,

Mashburn, Hamre, & Pianta, 2008). The master codes were established by two professionals with advanced degrees and experience in EC. One rater had a PhD in

early intervention and 20 years experience working with young children; the second

rater was a graduate student in child development who had 7 years experience

working with young children. The master coders were familiar with the literature on

rough and tumble play, and used the denition found in the literature (vigorous behaviours such as wrestling, grappling, kicking, tumbling and play ghting which appear

aggressive except for the playful framework (Flanders et al., 2009; Jarvis, 2007; Pellegrini, 1989, 1995; Pellegrini & Smith, 1998; Romano et al., 2005). Master codes

reported 37% observed aggression for the child in video 1 and 17% observed aggression for the child in video 2.

Interobserver reliability was calculated on an interval-by-interval basis measuring

the number of times the research assistant and primary researcher agreed or disagreed.

The formula used to calculate interobserver agreement was to divide the number of

agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and multiply by

100 (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). For video 1, overall reliability was 85%

(80% for appropriate play, 81% for aggression and 93% for non-occurrence of play);

for video 2, overall reliability was 92% (86% for appropriate play 97% for aggression

and 93% for non-occurrence of play). An inter-rater reliability analysis using the Kappa

statistic was also performed to determine consistency among raters. The inter-rater

reliability for the raters was found to be Kappa = 0.85 (p < 0.001) for video 1 and

Kappa = 0.89 (p < 0.001) for video 2 describing very substantial agreement (Viera &

Garrett, 2005).

Statistical analyses

The goal of this study was to distinguish whether child care providers rated higher or

lower than the master coding of aggression based on whether the child care provider

had completed a college degree or not. In addition, the data were analysed to determine

if child care providers with a greater number of years in the child care eld rated the

videotapes differently than child care providers with less experience in the child care

eld. In both instances, the dependent variable (child care providers aggression

ratings) was binned using the master code percentages as the guide. Scores at or

below the master code percentage of identied aggression were considered low;

scores above the master code percentage of identied aggression were considered

high. Generally, logistic regression is used to describe relationships between a dichotomous dependent variable and categorical or continuous independent variables (Peng,

Lee, & Ingersoll, 2002; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

Results

Descriptives

Child care providers reported aggressive behaviour on average of 28% of the observation sessions (range, 663; SD = 13.28) for video 1 and 24% (range, 660; SD =

10.30) for video 2. Child care providers with college degrees reported less aggression

than those without college degrees. Compared to the maser codes, 59% of non-degreed

C.F. DiCarlo et al.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

caregivers identied higher aggression for video 1 and 77% for video 2, whereas 50%

and 69% of child care providers with college degrees identied higher aggression,

respectively. Similarly, child care providers working in the eld less than ve years

identied more aggression than those with more experience. Compared to the master

codes, newer caregivers identied higher aggression, 66% for video 1 and 77% for

video 2, contrasted with 28% and 56% of child care providers who had been

working for 510 years and 17% and 56% for child care providers with more than

10 years of experience in the eld.

Logistic regression

Therefore, a logistic regression analysis was performed on aggression rating as the

outcome and two predictors: Education and Years of Experience. A test of the full

model with two predictors against constant-only model was statistically signicant (2

= 8.021, df = 2, p = .018), suggesting that the two predicators used in this study helped

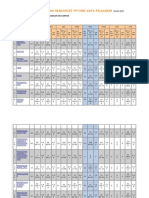

in identifying Aggressive Behaviours. Table 1 shows logistic regression coefcients,

Wald statistics, odds ratios and 95% condence intervals (CIs) for odds rations for

each predictor. The Wald statistic shows that both education level (x2(1) = 4.25,

p = .039) and the child care providers years of experience (x2(1) = 4.18, p = .041) reliably

predict identication of aggressive behaviours. For child care providers with higher education, the odds of reporting aggression in preschool-aged boys were decreased by three

units (95% CI, 1.058.48). Furthermore, child care providers with more years of experience had a one unit decrease in odds of reporting aggression (95% CI, 1.021.12). Child

care providers without college education are three times more likely to report aggressive

behaviour. In addition, child care providers with less years of experience working with

children are more likely to report aggressive behaviours.

Master codes and provider discrepancies

Child care providers identication of aggression by video and individual segment was

compared to the master codes by education category. Discrepancies between nondegreed providers and master codes for video 1 ranged from 4.8 to 77.1% (M =

30%) and for video 2 ranged from 2.4 to 78.3% (M = 20%). Discrepancies between

Table 1.

Logistic regression analysis of 94 caregivers aggression ratings.

(SE)

Walds 2

df

e

Odds Ratio

1.54 (.57)

1.10 (.53)

0.06 (.03)

7.419

4.250

4.184

1

1

1

.006

.039

.041

Predictor

Constant

Education

Years of Experience

Test

Overall model evaluations

Likelihood ratio test

Goodness-of-t test

Hosmer & Lemeshow

Note: R2L = .04, .08 (Cox & Snell), .11 (Nagelkerke).

95% CI for

odds ratio

Lower

Upper

0.21

2.99

1.06

1.05

1.02

8.48

1.12

df

8.02

.018

13.65

.091

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

Early Child Development and Care

degreed caregivers and the master codes for video 1 ranged from 0 to 36.4 (M = 21%)

and for video 2 ranged from 0 to 18.2% (M = 6%).

Child care providers identication of aggression by video and individual segment

was compared to the master codes by years of experience category. Discrepancies

between caregivers with less than ve years of experience and master codes for

video 1 ranged from 2.6 to 76.3% (M = 30%) and for video 2 ranged from 0 to

78.9% (M = 20%). Discrepancies between caregivers with 510 years of experience

and the master codes for video 1 ranged from 0 to 63.6% (M = 27%) and for video 2

ranged from 0 to 0 73.7% (M = 17%). Discrepancies between caregivers with more

than 10 years of experience and the master codes for video 1 ranged from 0 to

67.6% (M = 25%) and for video 2 ranged from 0 to 61.8% (M = 15%).

Reliability by predictor variables

The intra-class correlation (ICC) assesses rating reliability by comparing the variability

of different ratings to the total variation across all ratings and subjects. Due to the

nding that child care providers education and years of experience predicted the

amount of aggression they perceived in the videoed childrens ICCs, two-way

random model of absolute agreement was calculated to look at reliability between caregivers rating based on education and experience. The ICCs for perceived aggression

for child care providers without a four-year degree was .75 and .62 for videos 1 and

2, respectively. The reliability for caregivers with a college degree was .76 for video

1 and .71 for video 2. ICCs for the two videos for child care providers with less than

ve years experience were .64 and .62; 510 years experience were .74 and .80

and more than 10 years experience .83 and .62. The ICCs describe good to excellent

reliability in child care providers identication of aggression by similar years of

experience and education level (Cicchetti, 1994; Hallgren, 2012).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore whether there was a relationship between child

care providers level of education and their perception of aggression in preschool-aged

boys. The two major ndings of this exploratory study were that providers with more

education and experience working in the child care eld reported less aggression in preschool-aged boys and providers with similar experience and education showed high

levels of agreement in perception of the presence or absence of aggressive behaviours.

These ndings extend previous research which had established a relationship between

increased teacher education level and positive outcomes for young children (AbbottShim, Lambert, & McCarty, 2000; Sumsion, 2007; Whitebook, 2003) and increased

teaching experience and positive outcomes for young children (Dennis, 2009), to

include knowledge about the impact of education and experience on perceptions of

aggression in children. These ndings support continued research in the area of

increased education in teacher preparation and strategies to increase teacher retention,

as research suggests that both are associated with positive outcomes for young children.

In the present study, child care providers who had more education reported fewer

aggressive behaviour in the children depicted in the videotapes. Highly educated

child care providers are likely exposed to more coursework on child development;

and therefore more likely to have a better understanding of the distinction between

aggression vs. rough and tumble play. Field experiences are a requirement of every

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

C.F. DiCarlo et al.

teacher training programme, making the linkage between concepts learned in the university classroom and the EC classroom more apparent. These educational experiences

likely help them form a more consistent denition of what behaviours are aggressive. In

light of the present ndings, further investigation of specic content that aids in the

differentiation of rough and tumble play vs. aggression is warranted.

Presently, most child care staff are not required to have this type of educational

background prior to entering the workforce. National requirements for employment

in child care are a high school diploma or equivalent. In addition, there are no federally

mandated requirements for continuing education for child care staff (United States

Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014); with some states requiring as little as 12 clock

hours annually to maintain employment status (Louisiana Department of Social Services Bureau of Licensing, 2014). Recent efforts in many states, such as state-wide

quality rating systems, seek to increase the education levels of the child care worker.

Such efforts have the potential to support caregivers understanding and typical development in children leading to an increased accuracy of child care providers perception

of aggression in children.

This study also found that more experienced child care providers were more likely

to perceive fewer behaviours as aggression in young boys. The extant literature addressing experience and job performance and quality of care is decit. It is possible that

child care providers who have a disposition towards working with young children

are more likely to stay in the eld; however, caregivers who are not well suited to

working with young children may also be more likely to experience stress, and therefore leave the profession (Baumgartner & DiCarlo, 2013). Similar levels of experience

provide child care providers with a similar context and foundation to reference when

making developmental decision such as perceptions about aggression. Therefore,

these groups perceive not only similar frequencies of aggression but also similar behaviours as aggressive.

The impact of experience on teaching has some important possible implications for

practice. If more experienced teachers are more likely to have a more realistic view on

behaviour, this may also reect providers ability to implement developmentally appropriate practices and support self-regulation in children. However, if teachers are leaving

the eld, the result is that children have less exposure to seasoned providers who understand typical behaviour. In addition, fewer experienced teachers working the eld could

result in fewer models for novice child care providers.

It is clear from research that staff turnover is undesirable because it can directly

impact childrens development through loss of stability, consistency and continuity

(Whitebook, Howes, & Phillips, 1998). The turnover rate in child care is estimated

between 25% and 40% (Center for the Child care Workforce, 2004). Nationally,

child care workers earn less than $20,000 per year, which is commensurate with the

federal poverty level for a family of 4 (United States Bureau of Labor Statistics,

2014). Stress has been suggested as the underlying culprit in high turnover among

child care providers. Stress factors in child care can include work conditions, child

factors and life stressors outside the workplace (Baumgartner, Carson, Apavaloaie, &

Tsouloupas, 2009; Schmitt & Todd, 1995). Child care providers who experience

high levels of stress are less likely to provide quality of care and sensitivity crucial

to childrens upbringing and development (Belsky et al., 2007; Helburn, 1995).

In addition to the impact of job stress on attrition rates, when this high stress is

coupled with limited education, it may be particularly detrimental as these child care

providers are more likely to misperceive aggression, and thus may be more likely to

Early Child Development and Care

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

engage in punitive discipline. This is concerning because research has found that punitive discipline can affect childrens self-esteem, the development of self-regulatory

skills and the way the children are viewed by peers and other adults (Colman,

Hardy, Albert, Raffaelli, & Crockett, 2006). When child care providers use punitive

disciplinary practices, children are more likely to engage in externalising behaviours

(Colman et al., 2006). In other words, child care providers can contribute to childrens

aggressive behaviours. This is of particular importance in light of the ndings from the

present study, which suggest that child care providers with less education are misperceiving rough and tumble play as aggression. In these instances, child care providers

may be creating aggressive behaviour.

Limitations and future research

The present study was conducted in a limited geographic area in the south with a

majority African-American population. Future research should pull from a larger,

more diverse geographic area. All child care providers in the present study were

female; from this limited population, we cannot determine how the gender of the caregiver may impact interpretation of child behaviour. In addition, children depicted in the

videos were African-American and the majority of caregivers who rated the video were

also African-American. Future researchers may consider diversifying the ethnicity of

both the children studied and the caregiver raters.

Clinical signicance

There is evidence that high-quality preschool programmes better support the development of cognitive and social-emotional skills in children and may prevent conduct problems (Owens & Ring, 2007). Therefore, interventions that increase child care

providers training and higher education may decrease the number of children entering

kindergarten with aggression concerns. Therefore, it is recommended that the states

provide training classes to child care providers that specically address aggression in

young children.

In summary, the present study suggests that child care providers with a high school

education/GED perceived more aggression in preschool-aged boys as compared to

child care providers with higher levels of education. This suggests that child care providers with less education mislabel rough and tumble play as aggressive. Interventions

should be designed to encourage educational attainment among child care providers

who work in child care programmes. Training that specically addresses rough and

tumble play and the role it plays in young children socialisation skills is critical for

child care providers and the programmes where they are employed. In addition, child

care programmes should have policies and procedures that encourage child care providers to aspire to obtain higher education. The goal is to enhance the quality of life for

children, while providing them better opportunities to grow and develop into successful

and productive citizens.

Notes on contributors

Dr Cynthia F. DiCarlo is an associate professor in the School of Education in the College of

Human Sciences and Education at Louisiana State University. Her research focuses on facilitating behaviour change in educators to improve outcomes for young children.

10

C.F. DiCarlo et al.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

Dr Jennifer Baumgartner is an associate professor in the School of Education in the College

of Human Sciences and Education at Louisiana State University. Her research examines issues

of inter-contextual continuity among childrens developmental contexts, specically early

care and the family and the connections between philosophy and practice among adults in

childrens lives.

Dr Carrie Ota is an assistant professor in the Department of Child and Family Studies in the

Jerry & Vickie Moyes College of Education at Weber State University. Her research focus

includes early care and education, early childhood education and child development.

Mrs. Charlene Jenkins is an early childhood educator and the owner of the Infant Development Center in Zachary, Louisiana.

References

Abbott-Shim, M., Lambert, R., & McCarty, F. (2000). Structural model of head start classroom

quality. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(1), 115134.

Arnold, D. H., Grifth, J. G., Ortiz, C., & Stowe, R. M. (1998). Daycare interactions and teacher

perceptions as a function of teacher and child ethnic group. Journal of Research in

Childhood Education, 2, 143154.

Arnold, D. H., Ortiz, C., Curry, J. C., Stowe, R. M., Goldstein, N. E., Fisher, P. H., Yershova,

K. (1999). Promoting academic success and preventing disruptive behavior disorders

through community partnership. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 589598.

Barnett, S. W. (2003). Better teachers, better preschools: Student achievement linked to teacher

qualications. National Institute for Early Education Research, 2, 113.

Baumgartner, J., & DiCarlo, C. (2013, May/June). Reducing workplace stress. Child care

Exchange, pp. 6063.

Baumgartner, J. J., Carson, R. L., Apavaloaie, L., & Tsouloupas, C. (2009). Uncovering

common stressful factors and coping strategies among child care providers. Child Youth

Care Forum, 38(5), 239251.

Belsky, J., Vandell, D. L., Burchinal, M., Clarke-Stewart, K. A., McCartney, K., & Owen, M. T.

(2007). Are there long-term effects of early child care? Child Development, 78, 681701.

Burchinal, R. R., Cryer, D., Clifford, R. M., & Howes, C. (2002). Caregiver training and classroom quality in child care centers. Applied Developmental Science, 6, 211.

Campbell, S. B., & Ewing, L. J. (1990). Follow-up of hard to manage preschoolers: Adjustment

at age 9 and predictors of continuing symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, 31, 871889.

Carr, E. G., Taylor, J. C., & Robinson, S. (1991). The effects of severe behavior problems in

children on the teaching behavior of adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24(3),

523535.

Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284290.

Clarke-Stewart, K. A., Vandell, D. L., Burchinal, M., OBrien, M., & McCartney, K. (2002). Do

regulable features of child-care homes affect childrens development? Early Childhood

Research Quarterly, 17(1), 5286.

Colman, R. A., Hardy, S. A., Albert, M., Raffaelli, M., & Crockett, L. (2006). Early predictors of

self-regulation in middle childhood. Infant and Child Development, 15(4), 421437.

Colwell, M. J., & Lindsey, E. W. (2003). Teacher-child interactions and preschool childrens

perceptions of self and peers. Early Child Development and Care, 173(23), 249258.

Cooley, C. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribners.

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis. Upper Saddle

River, NJ: Merrill.

Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (Eds.). (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early

childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8 (3rd ed.). Washington,

DC: NAEYC.

Cunningham, A., Zibulsky, J., & Callahan, M. D. (2009). Starting small: Building child care

provider knowledge that supports early literacy development. Reading and Writing: An

Interdisciplinary Journal, 22(4), 487510.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

Early Child Development and Care

11

Dennis, S. E. (2009). Reexamining quality in early childhood education: Exploring the relationship between the work environment and the classroom (Doctoral dissertation). New York

University, Steinhardt.

Dobbs, J., & Arnold, D. H. (2009). Relationship between preschool teachers reports of childrens behavior and their behavior toward those children. School Psychology Quarterly,

24(2), 95105.

Dobbs, J., Arnold, D. H., & Doctoroff, G. L. (2004). Attention in the preschool classroom: The

relationship among child gender, child misbehavior, and types of teacher attention. Early

Child Development and Care, 174, 281295.

Early, D. M., Bryant, D., Pianta, R., Clifford, R., Burchinal, M., Ritchie, S., Barbarina, O.

(2006). Are teachers education, major, and credentials related to classroom quality and

childrens academic gains in pre-kindergarten? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23,

174195.

Early, D. M., Maxwell, K. L., Burchinal, M., Alva, S., Bender, R. H., Bryant, D., Zill, N.

(2007). Teachers education, classroom quality, and young childrens academic skills:

Results from seven studies of preschool programs. Child Development, 78(2), 558580.

Ewing, A., & Taylor, A. R. (2009). The role of child gender and ethnicity in teacher-child

relationship quality and childrens behavioral adjustment in preschool. Early Childhood

Research Quarterly, 24, 92105.

Finn, K., Johannsen, N., & Specker, B. (2002). Factors associated with physical activity in preschool children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 140(1), 8185.

Flanders, J. L., Leo, V., Paquette, D., Pihl, R. O., & Sguin, J. R. (2009). Rough-and-tumble

play and the regulation of aggression: An observational study of father-child play dyads.

Aggressive Behavior, 35, 285295.

Hagekull, B., & Hammarberg, A. (2004). The role of teachers perceived control and childrens

characteristics in interactions between 6-year-olds and their teachers. Scandinavian Journal

of Psychology, 45, 301312.

Hallgren, K. A. (2012). Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview

and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8(1), 2334.

Helburn, S. W. (Ed.). (1995). Cost, quality, and child outcomes in child care centers: Technical

report. Denver, CO: University of Colorado at Denver, Department of Economics, Center

for Research in Economic and Social Policy.

Hyson, M., Tomlinson, H. B., & Morris, C. A. S. (2009). Quality improvement in early childhood teacher education: Faculty perspectives and recommendations for the future. Early

Childhood Research & Practice, 11(1), 117.

Jarvis, P. (2007). Dangerous activities within an invisible playground: A study of emergent male

football play and teachers perspectives of outdoor free play in the early years of primary

school. International Journal of Early Years Education, 15(3), 245259.

Justice, L. M., Mashburn, A. J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2008). Quality of language and

literacy instruction in preschool classrooms serving at-risk pupils. Early Childhood

Research Quarterly, 23, 5168.

Louisiana Department of Social Services Bureau of Licensing. (2014). Louisiana child care

center class A minimum standards. Retreived from http://www.daycare.com/louisiana/

state-a.html

McLin, A. (2003). Emotion management: Assessing student behavior. Retrieved from ERIC

database. ED 482697.

Owens, E., & Ring, G. (2007). Difcult children and difcult parents: Constructions by child

care providers. Journal of Family Issues, 28(6), 827850.

Paquette, D., Carbonneau, R., Dubeau, D., Bigras, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2003). Prevalence of

father-child rough-and-tumble play and physical aggression in preschool children.

European Journal of Psychology of Education, 18(2), 171189.

Pellegrini, A. (1989). Categorising childrens rough and tumble play. Play and Culture, 2, 48

51.

Pellegrini, A. (1995). School recess and playground behaviour. New York: State University of

New York.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Smith, P. K. (1998). Physical activity play: The nature and function of a

neglected aspect of play. Child Development, 69(3), 609610.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 02:07 25 November 2014

12

C.F. DiCarlo et al.

Peng, C. J., Lee, K. L., & Ingersoll, G. M. (2002). An introduction to logistic regression analysis

and reporting. The Journal of Educational Research, 96, 314.

Phillips, D., Mekos, D., Scarr, S., McCartney, K., & Abbott-Shim, M. (2000). Within and

beyond the classroom door: Assessing quality in child care centers. Early Childhood

Research Quarterly, 15(4), 475496.

Rimm-Kaufman, S., Pianta, R. C., & Cox, M. J. (2000). Teachers judgments of problems to the

transition to kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15, 147166.

Romano, E., Tremblay, R. E., Boulerice, B., & Swisher, R. (2005). Multilevel correlates of

childhood physical aggression and prosocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child

Psychology, 33(5), 565578.

Rosin, H. (2010, July/August). The end of men. The Atlantic. Retrieved from www.theatlantic.

com/magazine/archive/2010/07-the-end-of-men/8135

Schmitt, D. M., & Todd, C. M. (1995). A conceptual model for studying turnover among family

child care providers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 10, 121143.

Smith, P. K., Smees, R., & Pellegrini, A. D. (2004). Play ghting and real ghting: Using video

playback methodology with young children. Aggressive Behavior, 30, 164173.

Sumsion, J. (2007). Sustaining the employment of early childhood teachers in long day care: A

case for robust hope, critical imagination and critical action. Asia-Pacic Journal of Teacher

Education, 35(3), 311327.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn

and Bacon.

Tannock, M. T. (2008). Rough and tumble play: An investigation of the perceptions of educators

and young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35(4), 357361.

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014). Occupational outlook handbook: Child care

workers. United States Department of Labor. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/ooh/

personal-care-and-service/childcare-workers.htm#tab-4

Viera, A. J., & Garrett, J. M. (2005). Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Family Medicine, 37(5), 360363.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, J. M., & Stoolmiller, M. (2008). Preventing conduct problems and

improving school readiness: Evaluation of the incredible years teacher and child training

programs in high-risk schools. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 471488.

Whitebook, M. (2003). Bachelors degrees are best: Higher qualications for pre-kindergarten

teachers lead to better learning environments for children. The Trust for Early Education.

Retrieved from http://www.leg.state.vt.us/PreKEducationStudyCommittee/Documents/

NCSL_bachelor_degrees_and_better_learning_pdf_Document.PDF

Whitebook, M., Howes, C., & Phillips, D. (1998). Worthy work, unlivable wages: The National

child care stafng study, 19881997. New York, NY: Center for the Child care Workforce.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- eMITC Skor Peserta eLifeMap EtoolDocument2 pageseMITC Skor Peserta eLifeMap Etoolryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- eLifeMap Student MarksDocument17 pageseLifeMap Student Marksryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- eLifeMap Student MarksDocument17 pageseLifeMap Student Marksryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- RIZQ ETool XLS DonemarkingDocument15 pagesRIZQ ETool XLS Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- RIZQ ETool XLS DonemarkingDocument15 pagesRIZQ ETool XLS Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nur Sofiya ETool PPT DonemarkingDocument7 pagesNur Sofiya ETool PPT Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Weekly Planner TemplateDocument1 pageWeekly Planner Templateryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- RIZQ ETool XLS DonemarkingDocument15 pagesRIZQ ETool XLS Donemarkingryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Week Topic Ties I-Think/ Teaching Aids: 1 Flash Cards Power Point Story Book WorksheetsDocument39 pagesWeek Topic Ties I-Think/ Teaching Aids: 1 Flash Cards Power Point Story Book WorksheetsZack AbrahamPas encore d'évaluation

- Lucky Stars Consulting Toolkit by SlidesgoDocument71 pagesLucky Stars Consulting Toolkit by SlidesgoFaniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jawapan Diagnostic Ting 5 2015 IctDocument6 pagesJawapan Diagnostic Ting 5 2015 IctJUN BINTI MOHD SABRI -Pas encore d'évaluation

- F3 EFC Module 2021Document18 pagesF3 EFC Module 2021ryn8011100% (1)

- Block Paper Printable TemplateDocument1 pageBlock Paper Printable Templateryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Activi Learning Outcomes: Week Topic Ties I-Think/ Teaching AidsDocument35 pagesActivi Learning Outcomes: Week Topic Ties I-Think/ Teaching AidsSang 90Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cornell Notes TemplateDocument1 pageCornell Notes Templateryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Exam F4ict Answer2009Document7 pagesFinal Exam F4ict Answer2009ryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- ECE PHD Policy HandbookDocument16 pagesECE PHD Policy Handbookryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ict Note6 140826215904 Phpapp02Document16 pagesIct Note6 140826215904 Phpapp02ryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- 4 - Construct 3 PDFDocument1 page4 - Construct 3 PDFMarseddi MakranPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis Pencapaian Headcount Ppt/Ar2 Mata Pelajaran: Sekolah: Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Sri Kampar Tingkatan: T5Document15 pagesAnalisis Pencapaian Headcount Ppt/Ar2 Mata Pelajaran: Sekolah: Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Sri Kampar Tingkatan: T5ryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Flow Chart Area ASKDocument1 pageFlow Chart Area ASKryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Example of S07.1Document12 pagesExample of S07.1ryn8011Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Review of Related Literature: Chapter - IiDocument49 pagesReview of Related Literature: Chapter - IiHindola SinghaPas encore d'évaluation

- Modified PROJECT SINAMAY MONITORING TOOL Mawab DistrictDocument2 pagesModified PROJECT SINAMAY MONITORING TOOL Mawab DistrictMai Mai ResmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Secondary Student'S Permanent Record: Pulo National High SchoolDocument24 pagesSecondary Student'S Permanent Record: Pulo National High SchoolChristian D. EstrellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Addressing The Future: Curriculum InnovationsDocument44 pagesAddressing The Future: Curriculum InnovationsAallhiex EscartaPas encore d'évaluation

- McqsDocument13 pagesMcqsaananyaa2020Pas encore d'évaluation

- SaviasachiDocument1 pageSaviasachiP.chandra Sekhar RajuPas encore d'évaluation

- Mainstreaming Community-Based Disaster Risk Management in Local Development PlanningDocument21 pagesMainstreaming Community-Based Disaster Risk Management in Local Development PlanningBabang100% (1)

- Inset Training DesignDocument3 pagesInset Training DesignJo Ann Katherine Valledor100% (1)

- First Term Report Card 2023-2024 - 38647 - 2Document2 pagesFirst Term Report Card 2023-2024 - 38647 - 2yaemikoraiden700Pas encore d'évaluation

- My Report CW 1Document13 pagesMy Report CW 1AkaahPas encore d'évaluation

- Economic Development Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesEconomic Development Research Paper Topicstug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Artikel PKNDocument8 pagesArtikel PKNAlya FaizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Solve Your ProblemsDocument2 pagesSolve Your ProblemsSheryl G. Padrigo100% (1)

- 8 Link Ers ContrastDocument2 pages8 Link Ers ContrastGabitza GabyPas encore d'évaluation

- Superhero Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesSuperhero Lesson Planapi-266581552Pas encore d'évaluation

- THE EFFECTS OF HAVING AN OFW PARENT ON THE ACADEMI Group 5Document3 pagesTHE EFFECTS OF HAVING AN OFW PARENT ON THE ACADEMI Group 5acelukePas encore d'évaluation

- Instructional Design in Outcome Based EducationDocument44 pagesInstructional Design in Outcome Based EducationTherirose AnnePas encore d'évaluation

- 2021 Code of Ethics For Professional Teachers ExplainedDocument18 pages2021 Code of Ethics For Professional Teachers ExplainedJoel De la Cruz100% (15)

- Pgm-Schedule - 2020-2021 - HRDC - PDFDocument1 pagePgm-Schedule - 2020-2021 - HRDC - PDFelanthamizhmaranPas encore d'évaluation

- P&G Hiring Process: Your Steps To SuccessDocument20 pagesP&G Hiring Process: Your Steps To SuccessJaveria ShujaPas encore d'évaluation

- An Empirical Study On Virtual Reality Assisted Table Tennis Technique TrainingDocument6 pagesAn Empirical Study On Virtual Reality Assisted Table Tennis Technique TrainingFrancis FrimpongPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre Test Fac LearningDocument2 pagesPre Test Fac LearningMaria Cristina ImportantePas encore d'évaluation

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The Philippinesrodolfo100% (4)

- Guidelines For Project Courses Including Capstone For Academic Session 2014-15Document9 pagesGuidelines For Project Courses Including Capstone For Academic Session 2014-15SatishKumarMauryaPas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Practice Nursing Role Delineation - Apllication - Strong Model AP - Mick - Ackerman - 2000Document12 pagesAdvanced Practice Nursing Role Delineation - Apllication - Strong Model AP - Mick - Ackerman - 2000Margarida ReisPas encore d'évaluation

- Sandie MourouDocument19 pagesSandie MourouSeda GeziyorPas encore d'évaluation

- Vincent Jones Resume 2020 EducationDocument1 pageVincent Jones Resume 2020 Educationapi-518914866Pas encore d'évaluation

- Case For Critical Analysis: Central City MuseumDocument2 pagesCase For Critical Analysis: Central City MuseumSophie EscobarPas encore d'évaluation

- Acr On Orientation - HGDocument4 pagesAcr On Orientation - HGJoylie PejanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prim Maths 6 2ed TR Letter For ParentsDocument2 pagesPrim Maths 6 2ed TR Letter For ParentsSsip ConsultationPas encore d'évaluation