Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Asperger Syndrome in Children

Transféré par

maria_kazaDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Asperger Syndrome in Children

Transféré par

maria_kazaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Asperger Syndrome in Children

Julie Schnur, RN, CPNP

INTRODUCTION

Purpose

To review Asperger syndrome characteristics, In 1944, a pediatrician named Hans Asperger observed a condition in

assessment tools, interventions, outcomes, a group of male children that he named autistic psychopathy; he named it

and the role of the nurse practitioner in as such because these children had a stable personality disorder marked by

diagnosing and caring for children with social isolation (Klin, 2003). However, others believe that ‘‘autistic personality

Asperger syndrome. disorder’’ is a better translation of Asperger’s original description (Volkmar,

Klin, Schultz, Rubin, & Bronen, 2000). These children demonstrated prob-

Data Sources lems with social integration and nonverbal communication associated with

Review of published literature on and diag- idiosyncratic verbal communication and an egocentric preoccupation with

nostic criteria of the condition. unusual and circumscribed interests. Asperger (1944) noted that these af-

fected individuals also had difficulties with empathy and intuition, as well as

Conclusions a tendency to be clumsy with awkward motor skills. These were only the

Asperger syndrome is a pervasive develop- observations of Asperger, and it was not until nearly 40 years later, in 1981,

mental disorder or an autism spectrum disor- when Lorna Wing introduced Asperger’s ‘‘autistic psychopathy’’ to the English

der that is thought to have an incidence language and renamed the cluster of characteristics as Asperger syndrome.

higher than that of autism. Asperger syn- Wing (1981) presented several additional difficulties, which afflicted chil-

drome is different from autism, with a lack

dren demonstrated in the first 2 years of life. These difficulties included a lack

of delayed language as the most distinct dif-

of normal interest and pleasure in people around them, a decreased quality

ference between Asperger syndrome and

and quantity of babbling, a significant decrease in shared interests, a signifi-

autism.

cant decrease in the wish to communicate either verbally or nonverbally,

a delay in speech acquisition, and no imaginative play or play that is con-

Implications for Practice

fined to one or two rigid patterns (Fitzgerald & Corvin, 2001; Wing).

Because of the importance of early diagnosis

Wing’s group, a case series of observations of 34 children, included a small

of Asperger syndrome for outcome improve-

ment, screening at all well-child visits from number of female subjects, which differed from Asperger’s male-only popu-

infancy on is of utmost importance to pri- lation (Klin, 2003; Wing). Ten years after Wing’s listing of general charac-

mary care pediatric nurse practitioners. With teristics, Gillberg (as cited in Fitzgerald & Corvin, 2001) presented six

early diagnosis, timely intervention is possi- diagnostic criteria: social impairments, narrow interests, repetitive routines,

ble, which is proven to show improvement speech and language peculiarities, nonverbal communication problems, and

in outcomes. motor clumsiness. His criteria are believed to be the closest to Asperger’s

characteristics.

Key Words Asperger syndrome is considered a pervasive developmental disorder

Pervasive developmental disorder, autistic (PDD). PDD is an umbrella term referring to a spectrum of disorders that

spectrum disorder, Asperger syndrome. differ with respect to either the number or type of symptoms present or the

age of onset of those symptoms (Szatmari et al., 2000). Others consider

Author Asperger syndrome as part of a group of disorders called autistic spectrum dis-

Julie Schnur, RN, CPNP, is a graduate of orders (ASD). However, Asperger syndrome is clinically differentiated from

Columbia University School of Nursing, autism and high-functioning autism by the absence of clinically delayed

New York, NY 10032. Contact Ms. Schnur speech (Rinehart, Bradshaw, Brereton, & Tonge, 2002; Volkmar et al.,

by e-mail at julie_schnur@hotmail.com 2000). It is characterized by social interaction impairments and restrictive or

repetitive interests with a lack of significant delays in language acquisition and

Acknowledgments with normal intelligence (Schatz, Weimer, & Trauner, 2002). The incidence

I thank Susan W. Ledlie, PhD, CPNP, for of Asperger syndrome is believed to be much higher than that of autism, with

her advice and support. A sincere thanks to its prevalence believed to be about 26–36 out of 10,000 school-aged children

(Ehlers & Gillberg, 1993; Kadesjö, Gillberg, & Hagberg, 1999).

302 VOLUME 17, ISSUE 8, AUGUST 2005

The purpose of this article is to review the diagnostic criteria

Rita Marie John, CPNP, for her help and guidance at of Asperger syndrome, describe the characteristic behaviors of

every stage of preparation of this manuscript. I thank children with this diagnosis, examine screening tools and inter-

Dr. Amy F. Cades, PhD, for her input and revisions of ventions, review outcomes of patients with Asperger syndrome,

the final version of this manuscript. and discuss the role of the nurse practitioner (NP) in the care

of patients with Asperger syndrome.

Asperger thought his syndrome to be different from Kanner’s DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

autism, often considered classic autism. This is still debated,

although most consider Asperger syndrome to be different from Several studies have attempted to validate Asperger syn-

autism but part of the autistic spectrum (Wing & Potter, drome as a distinct diagnosis from that of autism without

2002). Asperger believed that the main handicap of his disorder mental retardation (Klin, 2003). Eisenmajer et al. (1996) noted

was social in nature and was not due to delays or deficits in lan- three major differences: (a) there is no communication and

guage or intellect (Eisenmajer et al., 1996). Thus, although both imagination impairment criteria for Asperger syndrome, (b)

Asperger syndrome and autism are defined in terms of so- people with Asperger syndrome do not suffer from a significant

cial deficits, early language skills are preserved in Asperger delay in language, and (c) children with Asperger syndrome do

syndrome. not have a clinically significant delay in development of cogni-

The etiology of Asperger syndrome is not completely under- tion or age-appropriate self-help skills, adaptive behavior, and

stood. It is generally believed to have genetic causes combined curiosity about the environment. Thus, lack of language delays

with environmental factors. Asperger (1944) noticed a familial is the major differentiating factor between Asperger syndrome

nature of the characteristics, with a primarily male pattern of and autism.

transmission, as he often noted the traits in the fathers of the The ‘‘Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’’,

children he observed and is typically seen in a male-to-female fourth edition (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994),

ratio of 4:1 (Klin, 2003; Wing & Potter, 2002). Multiple genes known as the DSM-IV, and the ‘‘International Statistical Classifi-

have been linked to Asperger syndrome in children. However, cation of Diseases’’, 10th edition (World Health Organization,

although no specific gene has been identified as a cause of 1992), known as the ICD-10, both have diagnostic criteria

Asperger syndrome, it has been proposed that genetic factors for Asperger syndrome. Some of the criteria presented by the

play a greater role in Asperger syndrome than in autism (Foster DSM-IV differ from both Asperger’s original description and

& King, 2003; Rinehart et al., 2002). There have also been Gillberg’s subsequent criteria (Fitzgerald & Corvin, 2001). The

many suggestions surrounding other possible nongenetic causes ICD-10 diagnostic criteria are similar to those of the DSM-IV,

of autism and ASDs, including dietary components, environ- although they are closer to Gillberg’s. According to the DSM-IV

mental pollutants, antibiotic use, allergies, vaccines, and traces of (APA), if diagnostic criteria of both autism and Asperger dis-

neurotoxins found in some preservatives (Wing & Potter). None order are present, the diagnosis of autism takes priority.

of these have been scientifically validated (Wing & Potter). Diagnostic criteria from the DSM-IV are divided into two

Findings suggest that in the majority of cases, the underlying broad categories of qualitative impairment in social interaction

pathology of ASDs is present prenatally (Wing & Potter). and restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior,

Genetics play a major role in the development of autism and interests, and activities; patients must possess two or more of

ASDs as there is a male preponderance, with a ratio of approx- the listed qualitative impairments and at least one of the listed

imately four men to one woman in autism (Rapin, 2001). Asperger’s repetitive and stereotyped patterns. Qualitative impairments

original group consisted solely of men, and he noticed similar char- include marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal

acteristics in their fathers. Toward the end of the 1970s and early behaviors, failure to develop peer relationships appropriate for

1980s, male-to-female ratios for Asperger syndrome varied from their developmental age, lack of spontaneous seeking to share

four men to one woman to nine to one (Marshall, 2002). Kadesjö with others, and a lack of social or emotional reciprocity (APA,

et al. (1999) conducted a population study of 826 children born 1994). Restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns include an

in Karlstad, Sweden, in 1985, who were aged 6.7–7.7 years at the encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and

time of the study. Eight of the children were in special classes. restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal in either intensity

The authors chose to use a 50% sample of the remaining children, or focus, apparently inflexible adherence to specific nonfunc-

containing 224 boys and 185 girls. Twenty-one of the children had tional routines or rituals, stereotyped and repetitive motor man-

at least one parent who had entered from outside the Nordic coun- nerisms, and persistent preoccupation with parts of objects

tries. The authors found four children with Asperger syndrome––all (APA). In order for diagnosis, these criteria must present before

male––which is comparable to Asperger’s original population and 3 years of age, the impairment must be clinically significant,

adds credence to the belief that this condition is highly genetic in and must exclude a clinically significant delay in language,

etiology. The four boys with Asperger syndrome constituted cognition, or other skills (APA).

0.48% of their population––a rate of 48 in 10,000––compared to The ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) criteria for

earlier studies that found a rate of 26–36 per 10,000. Asperger syndrome include no clinically significant delays in

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF NURSE PRACTITIONERS 303

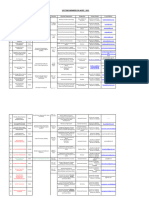

Table 1 Summary of Assessment Tools for Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorders, and Asperger Syndrome

General Tests for Autism and Autism Spectrum Disorders Specific Screening Tests for Asperger Syndrome

Screening tests The Australian Scale for Asperger Syndromea

Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT)—for The Screening Questionnaire for Asperger syndrome and

children aged 18 months other high-functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders in

Pervasive Developmental Disorder Screening Test—a school-aged children (1999)a,b

parent-completed survey Pervasive Developmental Disorders Questionnairea

Autism Screening Questionnaire (1999) Autism Spectrum Disorder Tests that have been successfully

Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (1999) used to recognize children with Asperger syndrome

Autism Diagnostic Interview

Diagnostic tests Autism Behavior Checklist (1980)

Behavior Rating Scale for Autistic and Atypical Gilliam Asperger’s Disorder Scale

Children (1966)

Childhood Autism Rating Scale (1988)

Autism Behavior Checklist (1980)

a

Found in Howlin (2000).

b

Ehlers et al. (1999).

spoken or receptive language or development, with single words Yeargin-Allsopp et al. (2003) found an equal prevalence of

spoken at or before 2 years of age, and communicative phrase autism––which they defined as autism, Asperger syndrome, and

use at the latest 3 years; qualitative abnormalities in reciprocal PDD not otherwise specified––in black and white children, a

social interaction; the affected person exhibits an unusually rate of 3.4/1000 children. However, they found that the male-

intense and circumscribed interest or restrictive and repetitive to-female ratio varied within different racial and ethnic groups.

behaviors; and the disorder is not attributable to another PDD. The authors sought to determine the prevalence of autism in

For the diagnosis of Asperger syndrome, the patient must a U.S. metropolitan area by using the area surrounding Atlanta,

demonstrate qualitative impairments in social interaction and Georgia. All the 289,456 children aged 3–10 years residing in

restricted patterns of interest. Of utmost importance is that a five-county metropolitan area were screened for autism (as

there are no language and communication criteria for diagnosis previously defined), with a gender split of 51% males, 49%

of Asperger syndrome; there should be no clinically significant females and a racial split of 58% white people, 38% black peo-

delay in language acquisition, cognition, and self-help skills ple, and 4% other. The authors found that 987 of the children

(Klin, 2003). Differential diagnoses for Asperger syndrome had autism (3.4/1000) and that while the rates were similar

include other ASDs or PDDs, attention deficit hyperactivity dis- between racial groups, the sex ratios varied between the groups,

order (ADHD), affective disorders, developmental disabilities, with the highest male-to-female ratio seen in black people. The

childhood onset schizophrenia, selective mutism, separation anxi- authors also found that the prevalence rates of autism varied

ety, stereotypic movement disorders, obsessive compulsive dis- between age groups, with the highest prevalence seen in 8-year-

order, and bipolar disorder (Fitzgerald & Corvin, 2001; Foster old children.

& King, 2003). While ADHD is on the list of differentials,

attention deficits are not a part of the diagnostic criteria for

Asperger syndrome. CHARACTERISTICS OF ASPERGER SYNDROME

Although attentional difficulties are not a part of the diag-

nostic criteria, the article by Schatz et al. (2002) ‘‘Brief report: Some characteristics of Asperger syndrome are social, devel-

Attention differences in Asperger syndrome’’ studied attentional opmental, and attentional warning signs that alert the NP dur-

differences between eight male children and young adults ing well-child care visits that the development is abnormal.

with Asperger syndrome (mean age of 16.00 years) and eight Other characteristics are more discrete because language devel-

matched male control subjects (mean age of 16.05 years). The opment usually is not delayed in these children; yet, other char-

subjects’ ethnicity was not specified. The authors found evi- acteristics, such as genetic factors, are even further concealed as

dence of attention deficits in most of the Asperger group and, they cannot be seen or noted by the naked eye when observing

while these deficits and hyperactivity are not included in the the patient.

diagnostic criteria, they have been observed in conjunction with The typical age of diagnosis for Asperger syndrome is 11

Asperger syndrome in other instances (Eisenmajer et al., 1996). years. However, parents can usually trace their concerns regarding

304 VOLUME 17, ISSUE 8, AUGUST 2005

their child’s development to as early as 30 months (Foster & spontaneous fashion, thus losing the tempo of the interaction’’

King, 2003; Wing & Potter, 2002). This is in accordance with (Klin, 2003, p. 104). These children are inclined to engage in

the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria that state that symptoms must long-winded, often one-sided, and sometimes incoherent,

be present before 3 years of age, although diagnosis occurs on although grammatically correct, speech (Klin). These children

average several years later. Therefore, it is important during tend to have problematic nonverbal communication, including

well-child visits that pediatric nurse practitioners (PNPs) screen limited gesturing, limited or inappropriate facial expression,

children from infancy on, and if concerns arise, to make the and a stiff and peculiar gaze; they also have characteristic pedan-

proper referrals so that timely intervention and therefore better tic speech, with normal expressive language but impaired com-

outcomes can occur. prehension (Foster & King, 2003). They are usually socially

isolated but tend not to be withdrawn when around other peo-

Social Skills ple. However, their approach toward others is often inappropri-

Children with Asperger syndrome display a similar clinical ate or eccentric in manner. They may have a history of delayed

picture. They often speak at the expected age and have an IQ motor acquisition, poor coordination, bouncy gait patterns, or

that is above 70, which may extend into the gifted range, but odd posture (Klin).

they tend to be socially inept with narrow interests (Rapin,

2001). Some children are clumsy or have poor motor skills. Attentional Characteristics

Although it is not part of the DSM-IV description of Asperger Eisenmajer et al. (1996) compared interviews of parents

syndrome, children often exhibit hyperactivity (Schatz et al., of 117 children with autism and Asperger syndrome in two

2002). Some propose that children with Asperger syndrome bet- Australian cities. The mean age of the autism group was 10.5

ter relate to adults than to their same age peers (Marshall, 2002). years and the male-to-female ratio was 39:9; the Asperger group

Szatmari et al. (2000) studied 68 children aged 4–6 years had a ratio of 61:8, with a mean age of 10.7 years. Although

diagnosed with autism or Asperger syndrome. Forty-seven chil- the DSM-IV states that ADHD is not to be diagnosed in peo-

dren were diagnosed with autism and 21 with Asperger syn- ple with a PDD, the authors found an increased likelihood of

drome. Two years later, at follow-up, one subject from each a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD. The increase in ADHD is in

group had left the study, and three (6.5%) of the autism and agreement with Schatz et al.’s (2002) study. Eisenmajer et al.

four (20%) of the Asperger group were women. It is important also found that children in the Asperger group were more likely

to note that in this study, the DSM-IV hierarchy rule was to engage in more prosocial behaviors. They had less severe eye

reversed, allowing Asperger syndrome to take priority. In com- contact avoidance at younger ages, more willingness and ability

paring the two groups, the authors found that children with to play with others as they got older, they were less likely to use

Asperger syndrome had better social skills at follow-up and that echolalic speech, and more likely to engage in long-winded

the outcome could not be attributed to initial differences in pedantic speech patterns (Eisenmajer et al.). Diagnosis of

intelligence and language. Both groups scored low on the social- Asperger syndrome usually occurs at an older age than autism,

ization assessment, but children in the Asperger group scored at and the authors suggest that this is because the level of impair-

least 1 standard deviation (SD) better than those in the autism ment of Asperger syndrome is less. However, the age at which

group (p = 0.001). The authors felt that these differences may parents first recognized problems in their child’s development

have been due to initial differences (Szatmari et al., 2000). On occurred at the same age for both. Foster and King (2003)

language and communication scales, the children in the reported that recent studies have also linked certain other char-

Asperger group usually scored within 1 SD of the normal popu- acteristics to children with Asperger syndrome, such as macro-

lation, whereas those with autism usually fell at least 2 SDs cephaly, abnormal motor coordination, and low birthweight.

below. Last, the authors propose that some findings suggest that

the differences between Asperger syndrome and autism may

largely be a function of timing, meaning that both groups may ASSESSMENT TOOLS

follow parallel paths but with different start and end ages.

Characteristics that may lead an NP to entertain a diagnosis There are currently several autism and Asperger syndrome

of Asperger syndrome include abnormal eye contact, a state of assessment and screening tools available. Some are completed

aloofness, failure to orient to name or to use gestures to point by parents, while others are completed either by lay personnel

out or show objects, a lack of interactive play, and a lack of or trained professionals. A summary of screening tests can be

interest in peers (Foster & King, 2003). Children with Asperger found in Table 1. Some of the tests, such as the Childhood

syndrome often possess an extensive knowledge of factual infor- Autism Rating Scale and the Autism Behavior Checklist, have

mation about a single, narrow topic in an intensive manner and acceptable levels of reliability and validity (Howlin, 2000).

are often able to recite that information and have discussions of The ‘‘Screening questionnaire for Asperger syndrome and

great depth on that topic. other high functioning autism spectrum disorders in school

Those with Asperger syndrome ‘‘may be able to describe cor- aged children’’, by Ehlers, Gillberg, and Wing (1999), is a ques-

rectly, in a cognitive and often formalistic fashion, other peo- tionnaire to be completed by lay informants. It is intended to

ple’s emotions, expected intentions and social conventions; yet, identify children in need of further evaluation, not as a diagnos-

they are unable to act upon this knowledge in an intuitive, and tic tool. The questionnaire consists of 27 items encompassing

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF NURSE PRACTITIONERS 305

elements of communication, social interaction, uncoordinated Pharmacologic interventions have recently been gaining

motor skills, and other associated symptoms, rated on a 3-point attention for their use in children with Asperger syndrome and

scale with 0 indicating normalcy and 2 indicating definite autism. Medications, including selective serotonin reuptake

abnormality. Possible scores range from 0 to 54 (Ehlers et al.), inhibitors and other antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics,

and it has been noted to be a useful screening device. The ques- and anticonvulsants, may alleviate troublesome behaviors and

tionnaire is used for children who are high functioning with symptoms but do not cure the underlying Asperger syndrome

normal to above-normal intelligence. However, it does not differ- (Foster & King, 2003; Rapin, 2001).

entiate between Asperger syndrome and other high-functioning

autistic disorders (Ehlers et al.).

According to Foster and King (2003), caution must be used THE ROLE OF THE NURSE PRACTITIONER

in screening children, especially those under 3, who possess fea-

tures of general ASDs as they may attract a diagnosis of PDD No data are available for a large U.S. population, but even if

possibly due to the presence of a significant developmental conservative rates of Asperger syndrome, autism, and other ASDs

delay. A potential benefit of screening is that there may be apply, NPs can expect to care for at least one child with these

earlier diagnosis. However, in high-functioning children, who disorders during their careers (American Academy of Pediatrics,

often lack a language delay and have average or above-average Committee on Children with Disabilities, 2001). The roles of

cognition, diagnosis often is not made until school age or later the NP include early diagnosis, providing anticipatory guidance,

(Baird et al., 2001). About 25% of children in any given pri- preparation for medical procedures, continuity of care, and fam-

mary care practice exhibit some level of developmental prob- ily or parental counseling.

lems, but less than 30% of primary care providers perform

screening tests at well-child visits (Filipek et al., 2000). Many Early Diagnosis

tools are good, but some primary care providers may prefer It can be argued that the most important role of the NP is

screening tools that are quick to administer or that are parent early diagnosis of Asperger syndrome. Parental concerns regard-

completed as time for primary care visits are limited, and these ing their child’s development should be of the utmost impor-

types of tools may decrease the amount of time for test adminis- tance and, if found, should lead to additional assessment. The

tration, therefore increasing the time to discuss the test results increasing importance of early diagnosis is supported by

with parents. research showing that patients who have early, consistent, and

appropriate intervention have improved outcomes (American

Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabil-

INTERVENTIONS ities, 2001). Continual developmental surveillance and screen-

ing at serial well-child visits is important. Only using very early

Clinical assessment is more effectively accomplished by an screening methods may miss later onset autism and Asperger

interdisciplinary team and should include a developmental and syndrome (Baird et al., 2001), whereas only using later screen-

health history, an assessment of communication and psychol- ing methods may cause children to be diagnosed later and thus

ogy, and a diagnostic exam that should be able to rule out dif- miss out on much needed early interventions. The NP’s ability

ferential diagnoses (Klin, 2003). Treatment methods are more to note behaviors typical of Asperger syndrome and a reliance

beneficial if they are multimodal and strategies vary for children on key elements of history, such as parental reports, is impor-

of different ages. In creating interventions, it is important to tant in providing proper early diagnosis (American Academy of

remember that they should be customized to the individual Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities). Outcome

child. Interventions should be tailored to the child’s develop- improvement for the child is possible with early diagnosis and

mental and behavioral needs and to the family’s coping style timely intervention.

and available resources (American Academy of Pediatrics, Com- Research has indicated that there is an extremely high occur-

mittee on Children with Disabilities, 2001). rence risk for Asperger syndrome and other ASDs in subsequent

Because of the various clinical presentations of children with siblings of an affected child. The American Academy of Pediat-

Asperger syndrome, individualized therapy is very important. rics, Committee on Children with Disabilities (2001) states that

Evidence has shown that intensive and early individualized edu- early diagnosis is important to ensure that parents can get

cation alters outcomes for all children with Asperger syndrome timely genetic counseling before the conception of other chil-

and autism (Rapin, 2001). In older children, who are well func- dren. Early diagnosis is also important if subsequent siblings

tioning and intelligent, the major goal is integration into a regu- have already been born so that they may receive timely assess-

lar classroom. Mainstreaming can be for part of or for the whole ment and, if present, may receive the proper diagnosis. The

day, often with the help of an individual or shared aide to keep reverse is also true: this information may be helpful in a younger

the child focused on the assignments or activities (Rapin). child who has been diagnosed whose older sibling has a sus-

Adolescents may benefit from social skills training programs pected ASD.

and groups, which could aid them in coping more effectively According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, Com-

with the changing social goals encountered during adolescence mittee on Children with Disabilities (2001), early manage-

(Rapin). ment strategies include parental education and support, early

306 VOLUME 17, ISSUE 8, AUGUST 2005

intervention for children under 3 years or school-based special for pediatric primary care providers who treat children with

education for children over 3, behavior management, commu- Asperger syndrome and ASDs. Some of the recommendations

nity services, medical treatments, and alternative therapies. have already been covered, but a summary includes monitoring

Referrals for, and implementation of, occupational therapy and all areas of development at each well-child visit, genetic counsel-

physical therapy services are also part of the role of the NP and ing for families, becoming familiar with alternative therapies,

contribute to the multimodal treatment. providing comprehensive care to the child, and providing the

opportunity for age-appropriate interventions (American Acad-

Anticipatory Guidance emy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities).

Anticipatory guidance geared toward both parents and the In terms of continuity of care and medical procedures, it is

patient is important. Vocational counseling may be helpful for important to avoid rapid changes of caregivers and to opt for

older children and adolescents in order to find careers for which a more gradual method of transferring care such as introduction

they can make the most of their strengths and in which they of new people, places, and procedures over time. This decreases

will not be disqualified because of their poor social skills the anxiety and is less disruptive to the child’s rigid routines.

(Rapin, 2001). Patients should also be taught about their diag-

nosis, with emphasis placed on maintaining self-esteem and

facilitating acceptance of interventions (Rapin). Anticipatory Counseling

guidance for parents includes providing training in behavior Strategies to increase the overall functional status of a

management, such as teaching them how to manage problem- school-aged child with Asperger syndrome includes decreasing

atic behaviors and helping to foster their child’s positive social maladaptive and repetitive behaviors and helping the family

skills (Rapin). Providing parents with other resources, such as manage the stress associated with raising a child with Asperger

local mental health agencies and credible Internet sites, is also syndrome (American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on

very helpful (Marshall, 2002). One resource for parents and Children with Disabilities, 2001). Brothers and sisters of diag-

healthcare providers is Act Early, a Web site from the Centers nosed children need an honest and truthful explanation of their

for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth sibling’s disorder because they may not receive as much parental

Defects and Developmental Disabilities (n.d.), that includes attention due to a focus on the child with Asperger syndrome.

information about ASDs and developmental milestones in chil- The whole family also needs support, counseling, in-home help,

dren of different ages. The information is available in both and respite care (Rapin, 2001). Coplan (2000) discusses a model

Spanish and English (www.cdc.gov/actearly). for parental counseling that is based on what he believes to be

While NPs and other primary care providers are not capable four commonly accepted premises: (a) atypical development

of determining a child’s outcome at the time of diagnosis, they occurs on a spectrum from mild to severe, (b) the phenotypic

are able to provide anticipatory guidance in terms of a possible expression of ASDs varies with age, (c) an ASD of any degree

trajectory and the child’s potential ability for development. can occur in combination with any degree of intelligence, and

Parents can use this information as a guideline for plotting and (d) long-term prognosis for an individual child is representative

assessing their child’s progress over time because a child with a of the impact of both the ASD and the child’s level of cognitive

milder ASD and normal intelligence tends to undergo a predict- ability or delay. Some suggestions for helpful coping strategies

able progression as he or she gets older (Coplan, 2000). Children for children with Asperger syndrome and their families include

with Asperger syndrome improve with maturity and age as they keeping a schedule, using clear communication, gradually intro-

progress into adulthood and are able to hold jobs and live inde- ducing change, planning for physical activity, providing encour-

pendently (Marshall, 2002; Szatmari, Bremner, & Nagy, 1989). agement to the child via positive feedback, and working with

Coplan (2000) suggests that children or adolescents who the child’s particular interests and strengths (Marshall, 2002;

may accidentally or innocently participate in socially unaccept- Olney, 2000).

able behaviors should wear a MediAlert identification to pro-

vide them protection. Marshall (2002) states that at school,

because of social isolation, these children may feel alone and CONCLUSION

may even be the focus of ridicule from classmates, at times so

severe as to drive them to suicidal ideation, anxiety, depression, While some people consider Asperger syndrome and high-

and possibly suicide. Therefore, extra attention should be paid functioning autism to be one and the same, they are in fact

when a child with Asperger syndrome presents with depression different entities. Clinically delayed language is the most dis-

or extreme sadness. Because of the significant delays in social tinguishable difference between autism and Asperger syndrome.

skills, and the often lacking ability to read others’ nonverbal Those with Asperger syndrome tend to have normal or above-

cues, adolescents are at risk for being victims of sexual assault normal intelligence. School-aged children with Asperger syn-

(Marshall). drome also tend to have more circumscribed interests and are

capable of possessing a large amount of factual information

Preparation for Procedures and Continuity of Care about isolated topics.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Chil- Screening and surveillance methods are important to identify

dren with Disabilities (2001) has provided recommendations children who are in need of further evaluation and testing.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF NURSE PRACTITIONERS 307

Developmental surveillance and screening should be performed in school age children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,

at all well-child visits for children ranging from infancy to 29(2), 129–141.

school aged, and even later if there are concerns surround- Eisenmajer, R., Prior, M., Leekam, S., Wing, L., Gould, J., Welham, M., et al.

ing social interactions, learning, or behavior problems. While (1996). Comparison of clinical symptoms in autism and Asperger’s dis-

early diagnosis is important, screening methods should continue order. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychia-

until well into school age as Asperger syndrome is more often try, 35(11), 1523–1531.

diagnosed in school-aged children and less frequently in Filipek, P. A., Accardo, P. J., Ashwal, S., Baranek, G. T., Cook, E. H., Jr.,

infancy. Dawson, G., et al. (2000). Practice parameter: Screening and diagnosis of

Several possibilities exist for future research for Asperger syn- autism. Neurology, 55, 468–479.

drome. These include clarification of its etiology that could Fitzgerald, M., & Corvin, A. (2001). Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of

potentially help in other realms, such as prenatal diagnosis and Asperger syndrome. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7, 310–318.

genetic counseling, avoidance of environmental triggers (if pres- Foster, B., & King, B. H. (2003). Asperger syndrome: To be or not to be?

ent), and better comprehension of the underlying pathophys- Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 15(5), 491–494.

iology of Asperger syndrome for the future development of Howlin, P. (2000). Assessment instruments for Asperger syndrome. Child

specific pharmacologic treatments (Rapin, 2001). Identification Psychology & Psychiatry Review, 5(3), 120–129.

of the chromosome(s) involved in Asperger syndrome may also Kadesjö, B., Gillberg, C., & Hagberg, B. (1999). Brief report: Autism and

influence treatments. Asperger syndrome in seven-year-old children: A total population study.

Continuing studies of the validity, reliability, specificity, and Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29(4), 327–331.

sensitivity of Asperger syndrome tests and the creation of other Klin, A. (2003). Asperger syndrome: An update. Revista Brasileira de

tests, if necessary, are another realm of research that could Psiquiatria, 25(2), 103–109.

benefit Asperger syndrome. While screening tests do exist, the Marshall, M. C. (2002). Asperger’s syndrome: Implications for nursing prac-

potential for development of a diagnostic tool specific for diag- tice. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 23, 605–615.

nosis of Asperger syndrome is needed to test those children who Olney, M. F. (2000). Working with autism and other social-communication

are referred for further evaluation. disorders. Journal of Rehabilitation, 66, 51–56.

Rapin, I. (2001). An 8-year-old boy with autism. Journal of the American

Medical Association, 285(13), 1749–1757.

REFERENCES Rinehart, N. J., Bradshaw, J. L., Brereton, A. V., & Tonge, B. J. (2002). A clini-

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities. cal and neurobehavioral review of high-functioning autism and Asperger’s

(2001). The pediatricians role in the diagnosis and management of autistic disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36, 762–770.

spectrum disorder in children. Pediatrics, 107(5), 1221–1226. Schatz, A. M., Weimer, A. K., & Trauner, D. A. (2002). Brief report: Attention

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of differences in Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental

mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Disorders, 32(4), 333–336.

Asperger, H. (1944). Autistic psychopathy in childhood. Translated and Szatmari, P., Bremner, R., & Nagy, J. (1989). Asperger’s syndrome: A review

annotated by U. Frith (Ed.) in Autism and Asperger syndrome (1991). of clinical features. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 34(6), 554–560.

Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. Szatmari, P., Bryson, S. E., Streiner, D. L., Wilson, F., Archer, L., & Ryerse, C.

Baird, G., Charman, T., Cox, A., Baron-Cohen, S., Swettenham, J., Wheelwright, (2000). Two-year outcome of preschool children with autism or Aperger’s

S., et al. (2001). Screening and surveillance for autism and pervasive syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1980–1987.

developmental disorders. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 84, 468–475. Volkmar, F. R., Klin, A., Schultz, R. T., Rubin, E., & Bronen, R. (2000).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects Asperger’s disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(2), 262–267.

and Developmental Disabilities. (n.d.). Learn the signs. Act early. Retrieved Wing, L. (1981). Asperger’s syndrome: A clinical account. Psychological

October 14, 2004, from www.cdc.gov/actearly Medicine, 11, 115–129.

Coplan, J. (2000). Counseling parents regarding prognosis in autistic spectrum Wing, L., & Potter, D. (2002). The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders:

disorder. Pediatrics, 105(5), 1–3. Retrieved October 7, 2003, from http:// Is the prevalence rising? Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/105/5/e65 Research Reviews, 8(3), 151–161.

Ehlers, S., & Gillberg, C. (1993). The epidemiology of Asperger syndrome: World Health Organization. (1992). International statistical classification of

A total population study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and diseases and related health problems. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

Allied Disciplines, 34(8), 1327–1350. Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Rice, C., Karapurkar, T., Doernberg, N., Boyle, C., &

Ehlers, S., Gillberg, C., & Wing, L. (1999). A screening questionnaire for Murphy, C. (2003). Prevalence of autism in a US metropolitan area. Journal

Asperger syndrome and other high-functioning autism spectrum disorders of the American Medical Association, 289(1), 49–55.

308 VOLUME 17, ISSUE 8, AUGUST 2005

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (Updated), A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsD'EverandAutism Spectrum Disorder (Updated), A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Asperger's Syndrome Bible: Autism Spectrum Disorders & Managing relationships, social skills, therapy & parenting of aspergers from the inside out,for children, teens,boys and girls to adulthoodD'EverandThe Asperger's Syndrome Bible: Autism Spectrum Disorders & Managing relationships, social skills, therapy & parenting of aspergers from the inside out,for children, teens,boys and girls to adulthoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Aspergers in AdulthoodDocument12 pagesAspergers in AdulthoodNick Judson100% (1)

- Asperger's Syndrome A Clinical Account. - tcm339-166245 - tcm339-284-32Document16 pagesAsperger's Syndrome A Clinical Account. - tcm339-166245 - tcm339-284-32andrei crisnic100% (1)

- Asperger'S Syndrome: Vicente V. PanganibanDocument23 pagesAsperger'S Syndrome: Vicente V. PanganibanMaricar Ramota100% (1)

- Meeting Special Needs: A practical guide to support children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (Autism)D'EverandMeeting Special Needs: A practical guide to support children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (Autism)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aspergers Syndrome Through The LifespanDocument8 pagesAspergers Syndrome Through The LifespanAdnan Zaki BunyaminPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrant's: Javiera Mora Leslie Vejar Teacher: Mrs. Monica Rodriguez Date: 27/ December/ 2011Document13 pagesIntegrant's: Javiera Mora Leslie Vejar Teacher: Mrs. Monica Rodriguez Date: 27/ December/ 2011Leslie Vejar Seguel100% (3)

- Asperger Syndrome and AdultsDocument4 pagesAsperger Syndrome and AdultsAnonymous Pj6Odj100% (1)

- Early Expression of Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument39 pagesEarly Expression of Autism Spectrum Disordersjyoti mahajanPas encore d'évaluation

- Asperger's and CreativityDocument13 pagesAsperger's and CreativityDouglas Eby50% (2)

- Prepared By: Saba Ahmed (Clinical Psychologist)Document48 pagesPrepared By: Saba Ahmed (Clinical Psychologist)Rana Ahmad GulraizPas encore d'évaluation

- From Anxiety To Meltdown: How Individuals On The Autism Spectrum Deal With Anxiety, Experience Meltdowns, Manifest Tantrums, and How You Can Intervene Effectively - PsychologyDocument4 pagesFrom Anxiety To Meltdown: How Individuals On The Autism Spectrum Deal With Anxiety, Experience Meltdowns, Manifest Tantrums, and How You Can Intervene Effectively - PsychologyfobisokaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Association Between Theory of Mind, Executive Function, and The Symptoms of Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument15 pagesThe Association Between Theory of Mind, Executive Function, and The Symptoms of Autism Spectrum DisorderRaúl VerdugoPas encore d'évaluation

- Increased Sensitivity To Mirror Symmetry in AutismDocument5 pagesIncreased Sensitivity To Mirror Symmetry in AutismRadek JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism Prof. Joesoef SimbolonDocument31 pagesAutism Prof. Joesoef SimbolonYanthieHardiantyPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism BasicsDocument9 pagesAutism Basicsgierman1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Manual AspergerDocument309 pagesManual AspergerCindy Ramona FaluvegiPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment and Diagnosis AutismDocument12 pagesAssessment and Diagnosis AutismPanaviChughPas encore d'évaluation

- Overview of Aspergers SyndromeDocument2 pagesOverview of Aspergers Syndromeapi-237515534100% (1)

- Early Regression in Social Communication in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A CPEA Study (Luyster Et Al 2005)Document26 pagesEarly Regression in Social Communication in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A CPEA Study (Luyster Et Al 2005)info-TEAPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism and Math TalentDocument3 pagesAutism and Math TalentNafisah BaharomPas encore d'évaluation

- Autistic Spectrum Disorder PresentationDocument9 pagesAutistic Spectrum Disorder PresentationKanderson113Pas encore d'évaluation

- Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument58 pagesAutism Spectrum DisorderPriscilla ChumrooPas encore d'évaluation

- Gross Motor 1 2: ST NDDocument3 pagesGross Motor 1 2: ST NDIloveshairavenice BundangPas encore d'évaluation

- Emotional CPR - AustraliaDocument1 pageEmotional CPR - AustraliaSharon A Stocker0% (1)

- Dokumen - Tips Introduction To The Ablls RDocument49 pagesDokumen - Tips Introduction To The Ablls Rعلم ينتفع بهPas encore d'évaluation

- Family Functioning and Behaviour Problems in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders The Mediating Role of Parent Mental HealthDocument10 pagesFamily Functioning and Behaviour Problems in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders The Mediating Role of Parent Mental HealthPETTIT ALCONSPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism and Education-The Ongoing BattleDocument20 pagesAutism and Education-The Ongoing BattleTommy KindredPas encore d'évaluation

- AutismDocument25 pagesAutismfrandywjPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism BrochureDocument2 pagesAutism Brochureapi-228006451100% (1)

- Challenge of Co Morbidity and Treatment in Autism 131027Document49 pagesChallenge of Co Morbidity and Treatment in Autism 131027Autism Society Philippines75% (4)

- Understanding Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asds) :: An IntroductionDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asds) :: An IntroductioneviherdiantiPas encore d'évaluation

- GARS 2 - ArticleDocument20 pagesGARS 2 - ArticleGoropadPas encore d'évaluation

- NIH Public AccessDocument23 pagesNIH Public AccessBárbara AndreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Children and Adults With Asperger S SyndromeDocument15 pagesCognitive Behaviour Therapy For Children and Adults With Asperger S SyndromeSimona Bejinariu100% (1)

- Lucy Barnard-Brack - Revising Social Communication Questionnaire Scoring Procedures For Autism Spectrum Disorder and Potential Social Communication DisorderDocument1 pageLucy Barnard-Brack - Revising Social Communication Questionnaire Scoring Procedures For Autism Spectrum Disorder and Potential Social Communication DisorderAUCDPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism and Asperger Syndrome by Simon Baron-CohenDocument170 pagesAutism and Asperger Syndrome by Simon Baron-CohenCristina100% (3)

- The Autism Spectrum QuotientDocument11 pagesThe Autism Spectrum QuotientIntellibrainPas encore d'évaluation

- Hyperlexia EssayDocument11 pagesHyperlexia Essayapi-286086829100% (1)

- Psychology Project 2016-2017: The Indian Community School, KuwaitDocument21 pagesPsychology Project 2016-2017: The Indian Community School, KuwaitnadirkadhijaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Identification of Autistic Adults’ Perception of Their Own Diagnostic Pathway: A Research Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of Master of Autism at Sheffield Hallam UniversityD'EverandThe Identification of Autistic Adults’ Perception of Their Own Diagnostic Pathway: A Research Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of Master of Autism at Sheffield Hallam UniversityPas encore d'évaluation

- Non-Verbal Learning DisorderDocument3 pagesNon-Verbal Learning Disorderapi-531843492Pas encore d'évaluation

- AutismDocument2 pagesAutismapi-314847014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Expo 3 NEPSY II A Developmental Neuropsychological AssessmentDocument23 pagesExpo 3 NEPSY II A Developmental Neuropsychological AssessmentHugo Cruz LlamasPas encore d'évaluation

- Gifted or AutisticDocument10 pagesGifted or AutisticGreat ThinkersPas encore d'évaluation

- Intervention AutismDocument41 pagesIntervention AutismIgnacio Nicolas DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaching Out Autism Related MaterialsDocument14 pagesReaching Out Autism Related MaterialsArunasis AdhikariPas encore d'évaluation

- An Exploratory Study On The Life of AutisticsDocument10 pagesAn Exploratory Study On The Life of AutisticsHuma MahmoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Don't Bully Me Because I'm Different. I'm Aspie and I'm Not Afraid to Show It.D'EverandDon't Bully Me Because I'm Different. I'm Aspie and I'm Not Afraid to Show It.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Autism ChecklistDocument3 pagesAutism ChecklistAmes0% (1)

- Kanner AutismDocument5 pagesKanner AutismNinelys CodPas encore d'évaluation

- JoDD 17-1 26-37 Schroeder Et AlDocument12 pagesJoDD 17-1 26-37 Schroeder Et AlEspíritu CiudadanoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Survival Guide For People With Asperger SyndromeDocument31 pagesA Survival Guide For People With Asperger SyndromeGema TrellesPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is AutismDocument20 pagesWhat Is AutismMarília LourençoPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism Spectrum Disorder With Videos 2022 - FAYDocument26 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorder With Videos 2022 - FAYNikky SilvestrePas encore d'évaluation

- Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument31 pagesAutism Spectrum DisorderBenson Munyan100% (1)

- DSM5-Reflexion in AutismDocument7 pagesDSM5-Reflexion in AutismBianca NuberPas encore d'évaluation

- An Educators Guide To Asperger SyndromeDocument101 pagesAn Educators Guide To Asperger SyndromeAura VăleanPas encore d'évaluation

- Asdv 2Document51 pagesAsdv 2api-434818140Pas encore d'évaluation

- Speaking Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesSpeaking Lesson PlanZee Kim100% (1)

- Las 1 - EAPPDocument2 pagesLas 1 - EAPPPaduada DavePas encore d'évaluation

- Detailed Lesson Plan in ArtsDocument5 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in ArtsNiño Ronelle Mateo Eligino83% (70)

- Essay Punctuation CheckerDocument4 pagesEssay Punctuation Checkerafibooxdjvvtdn100% (2)

- BCA - 4 Sem - Ranklist - May - June 2011Document30 pagesBCA - 4 Sem - Ranklist - May - June 2011Pulkit GosainPas encore d'évaluation

- TESTBANKDocument4 pagesTESTBANKGladz C Cadaguit100% (1)

- 6 Todo List BootstrapDocument2 pages6 Todo List BootstrapYonas D. EbrenPas encore d'évaluation

- DLLDocument3 pagesDLLMarvin ClutarioPas encore d'évaluation

- C.V. Judeline RodriguesDocument2 pagesC.V. Judeline Rodriguesgarima kathuriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Aromatherapy HandbookDocument62 pagesAromatherapy HandbookEsther Davids96% (24)

- LDM LeaDocument40 pagesLDM LeaLEAH FELICITASPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 2 - Case Study: PurposeDocument3 pagesAssignment 2 - Case Study: PurposeLoredana Elena MarusPas encore d'évaluation

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayDocument7 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayMArkPas encore d'évaluation

- AKOFE Life Members - 2012Document27 pagesAKOFE Life Members - 2012vasanthawPas encore d'évaluation

- ProfEd June 16 2023Document83 pagesProfEd June 16 2023Richmond Bautista VillasisPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Indian EducationDocument10 pagesHistory of Indian EducationSayali HaladePas encore d'évaluation

- IB Econ IA GuidanceDocument11 pagesIB Econ IA GuidanceKavin RukPas encore d'évaluation

- Starfall Kindergarten Lesson Plans Week5Document26 pagesStarfall Kindergarten Lesson Plans Week5Ashley YinPas encore d'évaluation

- Planned Parenthood Case IA SUPCTDocument54 pagesPlanned Parenthood Case IA SUPCTGazetteonlinePas encore d'évaluation

- Planning CommentaryDocument9 pagesPlanning Commentaryapi-443510939Pas encore d'évaluation

- Procurment Article ReviewDocument4 pagesProcurment Article Reviewkasim100% (1)

- A Study On Using Podcast To Facilitate English Listening ComprehensionDocument3 pagesA Study On Using Podcast To Facilitate English Listening ComprehensionLast TvPas encore d'évaluation

- Buddhism and PersonalityDocument20 pagesBuddhism and PersonalityLeonardoCervantesPas encore d'évaluation

- Explain The Verification and Falsification PrinciplesDocument2 pagesExplain The Verification and Falsification PrinciplesktPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan - Clasa A 3-ADocument3 pagesLesson Plan - Clasa A 3-AMihaela Constantina VatavuPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 4 Template Quantitative Article Qualitative Article: NSG3029 W4 Project Research Template Wildaliz ColonDocument4 pagesWeek 4 Template Quantitative Article Qualitative Article: NSG3029 W4 Project Research Template Wildaliz ColonMikey MadRatPas encore d'évaluation

- Ted 407 AutobiographyDocument3 pagesTed 407 Autobiographyapi-389909787Pas encore d'évaluation

- Detroit Cathedral Program Final 4-17-12Document2 pagesDetroit Cathedral Program Final 4-17-12Darryl BradleyPas encore d'évaluation

- IeetDocument63 pagesIeetfaraaz94Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kea NB191 2019 07 19 10 58 15Document4 pagesKea NB191 2019 07 19 10 58 15Rakesh S DPas encore d'évaluation