Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Ajap 2 1 4

Transféré par

Mushtaq Hussain KhanTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ajap 2 1 4

Transféré par

Mushtaq Hussain KhanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

American Journal of Applied Psychology, 2014, Vol. 2, No.

1, 22-26

Available online at http://pubs.sciepub.com/ajap/2/1/4

Science and Education Publishing

DOI:10.12691/ajap-2-1-4

Optimism and Quality of Life after Renal

Transplantation

Fatima Kamran*

Institute of Applied Psychology, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

*Corresponding author: fatimakamran24@yahoo.com

Received February 08, 2014; Revised February 27, 2014; Accepted March 13, 2014

Abstract Optimism is considered to influence Quality of Life (QoL) in a positive way. The longitudinal study

was carried out to find the impact of optimism (life orientation) on perceived Quality of life among renal transplant

recipients (RTRs) to see if optimism increases subjective QoL. The findings revealed a significant positive

correlation between optimism and perceived QoL, suggesting that optimist recipients tend to be more satisfied with

their overall life post- transplant. Recipients did not differ in levels of optimism on the basis of gender, marital status,

education, financial conditions and time since transplantation. Age was the only demographic factor found to be

negatively associated with optimism, suggesting that optimism decreases with increasing age. In order to clarify the

cause & effect relationship, a linear regression was carried out that showed that optimism does not predict QoL;

however, an increased QoL does predict optimism which is an interesting and unexpected finding. Optimism was

studied as a personality trait; however, it appeared to be more as an outcome of life experiences. A Cross lagged

Correlation analysis was carried out to clarify the causal direction of this relationship between optimism and QoL.

However, no clear causal direction was found indicative of an overlap among these constructs which seem to lack

distinctiveness as separate constructs.

Keywords: renal transplantation, life orientation, optimism, quality of life, renal transplant recipients,

psychosocial factors

Cite This Article: Fatima Kamran, Optimism and Quality of Life after Renal Transplantation. American

Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 2, no. 1 (2014): 22-26. doi: 10.12691/ajap-2-1-4.

1. Introduction

Organ transplantation is a surgical procedure that

influences an individuals physical health status and

psychological well-being. Kidney transplants are the most

commonly performed organ transplant with a high success

rate and newer developments that have increased the

survival rates (Fieberger, Mitterbauer, &Oberbauer 2004).

The loss and re-gain of a kidney implicates psychological,

clinical and environmental factors. How this surgical

procedure is experienced and perceived by each recipient

varies depending on the different socio-demographic, clinical

and psychological factors (Fisher, Gould, Wainwright, &

Fallon, 1998). This highlights the significance of personal

factors such as attitudes and health beliefs in influencing

Quality of life (QoL) after transplant.

Research attempting to investigate the impact of an

individuals life orientation on perception and satisfaction

of QoL has found that an optimistic approach to life may

reduce the risk of health problems and may actually help

people recover more quickly after experiencing a serious

life-changing event (Kivimaki, Vahtera, Elovainio,

Helenius., & Singh et al., 2005). People identified as

optimistic have a tendency to expect good or acceptable

outcomes in the future, while those at the other end of the

spectrum, pessimistic, and expect bad or unacceptable

outcomes or experiences (Carver &Scheier, 2001;

Scheier& Carver, 1985). Lin et al (2010) explored the

relationship between optimism and life satisfaction among

patients with end stage renal disease, with groups that

were waiting and non-waiting for transplantation. It was

found that both groups reported moderate levels of life

satisfaction, whereas, those in the non-waiting group had a

greater life satisfaction in general. However, all patients

were optimistic and optimism was positively associated

with life satisfaction. Besides that, other factors of

optimism, age, work ability, waiting transplantation or not

and marital status were significantly associated with life

satisfaction (Lin, Chiang Li, & Liu 2010). Therefore, it

was considered to analyze the impact of optimism on

perceptions of QoL after a major surgical experience of a

renal transplantation to find if recipients optimism

increases their satisfaction with QoL or vice versa.

Aims and objectives of the research

The main aim of the present study was to find out if

optimism influences recipients perceptions and

satisfaction with quality of life.

1.1. Research Questions

Do Optimist renal transplant recipients (RTRs) report

a better Quality of Life?

Do demographic differences in optimism influence

perceived Quality of Life?

American Journal of Applied Psychology

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

A longitudinal prospective cohort study was carried out

investigating demographic differences in optimism and

how it affects perceptions of QoL among RTRs recruited

from renal clinics in Lahore, Pakistan. A descriptive

design was used to examine QoL over a period of 15

months.

2.2. Participants & Recruitment

The sample size varied in all three points of assessment

due to sample attrition. At Wave 1, N = (150), Wave 2, N

= (147) and Wave 3, N = (144). These recipients had a

post-transplant time ranging from 6 months to 10 years

(Mean = 2.8 years, S.D = 1.5) and with normal graft

functioning.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Renal transplant recipients currently on a schedule of

regular follow-up appointments; age 18 years onwards

without any co-morbidity (existing physical or mental

disorders); not more than one previous transplant,

minimum basic formal schooling to equivalent of primary

school level, and healthy graft functioning as indicated by

follow up monitoring of renal function tests.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Renal transplant recipients with medical co-morbidities

or complications and/or psychological disorders; below

the age of 18 years, illiterate recipients with no formal

schooling; more than two kidney transplants in total, or

any other co-existing transplant e.g., liver, heart or lung

transplant along with a kidney transplant.

2.2.3. Measures

Demographic information collected included age,

gender, marital status, years of formal education,

employment status, household income and number of

dependents, familial background (rural/urban), and family

systems i.e. joint or nuclear. Housewives and students

were included in the unemployed category. Medical

information collected included basic clinical information

about approximate onset and duration of ESRD, dialysis

modality (hemodialysis, peritoneal or both) before

transplant and duration of dialysis, primary & secondary

nephrologic diagnosis to reveal the etiology of renal

failure, time since transplant, current medication

(immunosuppressant group and dosage), complete blood

profile with renal functions (including, serum creatinine,

blood urea, uric acid).

2.3. Quality of Life Index Kidney Transplant

Version 111 (1998)

The QoL Index developed by Ferrens& Powers (1984)

consists of 35 items and measures both satisfaction and

importance of various aspects of life. Importance ratings

are used to weight the satisfaction responses, so that

scores reflect the respondents' satisfaction with the aspects

of life they value. The instrument consists of two parts:

the first measures satisfaction with various aspects of life

23

and the second measures their importance. Scores are

calculated for overall QoL and four domains: health and

functioning, psychological/ spiritual, social and economic,

and family. Items that are rated as more important have a

greater impact on scores than those of lesser importance.

Satisfaction is rated from 1 = "very dissatisfied" to 6 =

"very satisfied", and importance is rated from 1 = very

unimportant to 6 = very important. Scores are

calculated by weighting each satisfaction response with its

paired importance response (Ferrans, 1990; Ferrans, 1996;

Ferrans& Powers, 1985, 1992; Warnecke, Ferrans,

Johnson, & et al., 1996). In previous studies, internal

consistency for the QoLI (total scale) was supported by

Cronbach's alphas ranging from .73 to .99 (Ferrans&

Powers, 1985).

2.4. Life Orientation Test (Revised) (L.O.TR;1994)

The LOT-R was developed to assess individual

differences in dispositional optimism versus pessimism

(Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). This measure has

been widely used in health research. The LOT-R is a 10item measure with four filler items, three positivelyworded items, and three reverse-coded items. Respondents

indicate their degree of agreement with statements using a

five-point response scale ranging from 1 = "strongly

disagree" to 2 = strongly agree." Negatively-worded

items are reversed, and a single score is obtained.

Cronbachs alpha for the total score on a 10 item scale is

estimated at .82 (Smith, Pope, Rhodewalt, &Poulton,

1989).

2.5. Data Collection

This three-wave longitudinal study investigating

optimism and perceived QoL among RTRs was conducted

over a period of 15 months, with a mean age of 33.33

years (ranging from 18 to 54 years). Three assessments

comprised of an initial baseline evaluation (Wave 1)

followed by Wave 2 assessment with an interval of 6

months. Finally, Wave 3 assessments were conducted with

a gap of one year following wave 2 assessment. The mean

age of recipients was 33.33 years (ranging from 18 to 54

years). The recipients were recruited as referrals from

physicians in renal out-patient units of private &

government hospitals in Lahore (Pakistan). The

assessments were conducted during their follow up

sessionsat the clinic individually.

2.6. Statistical Analysis Using Cross Lagged

Correlations

Path analysis was used to investigate causal

relationships between psychosocial factors influencing

recipients overall satisfaction with their QoL after a renal

transplant. Longitudinal data from participants over a

period of 15 months used to model lagged and crosslagged paths over three wave points of assessment after

transplant, with a baseline, followed by an interval of six

months (wave 1) and one year (wave 2). Causal

relationships might be inferred using cross lagged designs

in which variables are measured at least twice over time

(Kenny, 1975 Rogosa, 1980); Locascio, 1982). When we

need to compare the correlations between one set of

24

American Journal of Applied Psychology

variables with that between a second overlapping set of

variables in a longitudinal data comprising the same set of

participants, a cross lagged panel correlation analysis is

used. This design involves analysis of reciprocal

relationships between two or more variables that are

measured at each of the points in time. Applying it to the

present study, the comparison is made by analyzing the

correlation between, QoL at wave 1 and optimism

measured at wave 2, verses optimism measured at wave 1

and QoL at wave 2 controlling for the autocorrelations

between variables and the correlations between QoL and

optimism at each wave point. There are three points of

assessment, so it will also involve correlations between

QoL wave 2 and optimism wave 3 and vice versa as well.

The aim is to estimate and test the strength of the

relationship between the two sets of variables and

determine causal priority using Steigers (1980) formula,

to compare non overlapping variables.

3. Results

3.1. Life Orientation (Optimism) & QoL

The findings revealed that most recipients reflected an

optimist approach towards life in general.The scores

across three waves indicated a consistent pattern of

optimism over time (Table 1).

The above Cross lagged Correlations do not show any

significant difference in correlations among QoL and life

orientation at wave 1 and 2 (z = 0.65, p = 0.51) making it

unclear whether its the attitude towards life and level of

optimism that makes them less or more satisfied with their

overall life or those who are currently more satisfied with

their QoL tend to be more optimistic about their future too.

However at wave 2 and 3, the causal flow is from QoL to

optimism. (z = 2.12, p= 0.03), indicating that a more

satisfied QoL makes them more optimistic.

3.2. Demographic Factors &Optimism

The recipients level of optimism was analysed

considering their demographic background and the results

found that except age, no other demographic factor

influenced recipients level of optimism.

a) Age &Optimism: Significant negative associations

were found among recipients age and optimism across

three waves, (wave 1, r = -.201, p = .014, wave 2, r = -238,

p = .004, and wave 3, r = -.204, p = .015) suggesting that

older recipients tend to be less optimistic.

b) Gender differences inOptimism: No significant

gender differences were found in optimism.

Table 4. Gender differences in Optimism at Wave 1, 2 & 3

Optimism

Wave 1

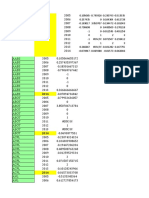

Table 1. Descriptive Scores on Optimism Wave 1, 2 & 3

Optimism

N

Means

S.D

Minimum

Maximum

Wave 1

146

14.13

3.84

7.00

20.00

Wave 2

146

14.69

4.44

2.00

22.00

Wave 3

144

14.51

2.65

7.00

19.00

Significant positive correlations were found among

optimism wave 1 and 2 (r = .304, p <.001) and a very

high correlation between wave 2 and 3 (r = .853, p < .001).

Besides inter-correlations, it was also significantly

associated with their satisfaction with overall QoL (Table 2).

Table 2. Correlations among Optimism & QoL

QoL Scores

Optimism-1

Optimism-2

Optimism-3

QoL Wave 1

.596**

.304**

.365**

QoL Wave 2

.411*

.423**

QoL Wave 3

.219**

**p < .001, *p< .005.

It seems that recipients with a positive life orientation

tend to report more satisfaction with their QoL or vice

versa. It could also be that QoL and life orientations are

aspects of the same thing because optimism is also a

perception of life as QoL.

Optimism and QoL were tested for causal priority. (See

Table 3).

Table 3. Cross Lagged Correlations among *Life Orientation (LO)&

QoL

**

p< .001, p< .005 List wise N = 144

Wave 2

Wave 3

Gender N Means S.D

Male

98 14.38

Female 48 13.60

Male

96 15.10

Female 48 13.91

Male

94 14.70

Female 47 14.00

df

Sig

3.70 1.159 144 .248 0.20 0.09

4.09

4.52 1.517 142 .131 0.27 0.13

4.23

2.61 1.482 139 .141 0.26 0.13

2.72

Dependent variable: Optimism.

c) Marital status & Optimism: To find if differences in

optimism exist among RTRs due to their marital status,

they were grouped into those In a relationship vs.

single due to low representation of other marital

categories.

Table 5. Marital Status and Optimism

Marital

N Means S.D

t

df Sig d

r

Status

In a

69 14.47 3.58 1.160 142 .248 0.19 0.09

Wave 1 relationship

Single

75 13.73 4.09

In a

68 14.73 4.30 .031 139 .975 0.00 0.00

Wave 2 relationship

Single

73 14.71 4.53

In a

68 14.57 2.49 .322 136 .748 0.05 0.02

Wave 3 relationship

Single

70 14.42 2.76

Dependent variable: Optimism.

Optimism

It was found that recipients in a relationship did not

differ in optimism as compared to singles, at any time,

suggesting no influence of marital status on recipients

optimism.

d) Education &Optimism:The impact of education

level on recipients attitude towards life was analyzed to

find if recipients with higher educational backgrounds

appeared to be more optimistic. The recipients were

categorized into three groups according to their formal

education. The groups included school-level, graduate and

post graduate recipients.

American Journal of Applied Psychology

25

The ANOVA showed that recipients with different

education levels did not differ in their optimism at wave 1,

but significant differences were found among these groups

at wave 2 and 3. Keeping in view the small effect size of

the observed differences in optimism cannot reliably be

attributed to their education level.

e) Employment Status &Optimism: The role of

employment on recipients life orientation was analyzed to

find if work status enhances optimism among recipients

by giving them a sense of being functional and

constructive. It was found that at wave 1, currently

employed RTRs (M = 14.61, S.D = 3.71) appeared to be

more optimistic than those who were not working (M=

13.25, S.D = 3.95) t (144) = 2.082, p = .039, d = 0.35, r =

0.17. No significant difference in optimism were found

among these groups at wave 2 (t (142) = .788, p = .432, d

= 0.13, r = 0.06 and wave 3 (t (139) = .092, p = .926, d =

0.01, r = 0.00, suggesting no impact of work status on

their life orientation.

f) Financial Conditions &Optimism: It was assumed

that recipients with stable financial conditions would be

more optimistic compared to those with less financial

sources and issues in affording the expensive lifelong

transplant medication. However, the findings showed on

the contrary that RTRs having different monthly incomes

did not differ in their life orientations (wave1, F (2, 143)

= .403, p = .669, 2 = .006, wave 2, F(2, 143) = 1.486, p

= .230, 2 = .021and wave 3, F (2,138) = 1.535, p = .219,

2 = .022). RTRs with high monthly incomes and stable

financial conditions did not report a more optimistic

approach towards life at any time.

g) Time since transplantation & Optimism: No

correlations were found among life orientation and time

since transplantation at any time, reflecting that their

attitude and approach towards life did not change with

time.

recipients perceive their life after transplant. Seligman

(1990) describes it as the way individuals perceive and

attend to obstacles within the context of their lives

(Cowan 2005). Optimistic people have a tendency to

expect positive and good future outcomes and events in

contrast to pessimists, who expect bad or unacceptable

outcomes or experiences (Carver &Scheier, 2001;

Scheier& Carver1985).

QoL in health outcomes is assessed considering the

satisfaction of patients with their physical functioning and

coping reflecting the efficacy of a specific intervention.

However, personal characteristics of the recipients

determine the variability in QoL satisfaction despite

similar physical health status. Calman (1984) defines QoL

as a gap between patients expectations and successes or

between present and preferred QoL and suggested that this

gap varies in the course of the sickness; and distinguishes

the potentiality from the current ability and underlines the

importance of having realistic goals (WHOQOLGroup,

1995; Testa& Simonson 1996). Therapeutic interventions

can be designed to work and reduce the gap between a

person's present QoL, their present aspirations and

realistic expectations for the future. This could be

achieved, by making recipients focus on what they have

in their present and not necessarily by changing the level

of expected future QoL. A transplant represents a decisive

event for patients and their caregivers. The attitudes of

recipients towards transplantation and life after

transplantation may influence their life satisfaction.

Analysis of optimism provides insights as to how

individuals perceive and attend to obstacles within the

context of their lives (Seligman, 1990), especially in case

of transplantation that involves, accepting, adapting and

coping with a transplanted kidney and its consequences.

Previous research examining the relationship between

optimism and life satisfaction among patients with endstage renal disease who decide to wait or not to wait for

kidney transplantation, found that all participants had

good optimism that was positively related to their life

satisfaction (Lin, Chiang and Liu 2010), suggesting that

having a positive life orientation can affect QoL

satisfaction. The present study explored whether a positive

approach and optimistic attitude towards life makes the

recipients more satisfied with their QoL or a satisfied QoL

makes them more optimistic. The study found that life

orientation and QoL were correlated and the predominant

causal effect is from QoL to Life orientation, i.e. having a

good QoL makes them more optimistic. Considering the

findings, it can be suggested that a more satisfied QoL

experience can lead to a positive attitude towards life in

general.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Life orientation (optimism) was measured as a trait-like

predisposition, but the findings showed that rather than

being a consistent personality trait, it appeared to be more

as an outcome of recipients life experiences that

determined their attitude towards self, others and life in

general instead of being a personality trait. The past

experiences tend to affect their present evaluations and

future aspirations. Optimism is considered a measure of

their attitude and approach towards life, to find how

The present study contributed towards an understanding

of psychological issues affecting perceived QoL among

Pakistani RTRs. Most RTRs with a good graft functioning

and normal general health reported a satisfied QoL

reflecting transplant efficacy in a developing country

where people live with issues of affordability and

availability of quality health care without any support by

the government. Interestingly, optimism is found more of

an attitude developed as a consequence of varying life

Table 6. Education &Optimismat Wave 1, 2 & 3

Optimism Education N Mean S.D

F

Sig

School level 35 13.75 4.03 F (2, 143) = 1.820 .166

Graduate 43 13.44 3.76

Wave 1

Post graduate 68 14.76 3.75

Total

146 14.13 3.84

School level 32 13.53 5.40 F (2, 141) = 4.158 .018

Graduate 45 13.88 4.36

Wave 2

Post graduate 67 15.82 3.74

Total

144 14.70 4.44

School level 31 13.61 3.00 F (2, 138) = 4.986 .008

Graduate 43 13.97 2.60

Wave 3

Post graduate 67 15.17 2.36

Total

141 14.46 2.66

Dependent variable: optimism

2

.025

.056

.067

26

American Journal of Applied Psychology

experiences rather than an enduring personality trait.

Recipients with a satisfied QoL tend to be more optimistic

instead of optimism improving perceptions of QoL. This

suggests that improvement in environmental and social

conditions determine their attitude and orientations about

present and future life.

6. Future Implications & Recommendations

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

The findings of this longitudinal study provide the

ground work for future research on psychological aspects,

particularly recipients personal characteristics influencing

QoL after transplantation. Most research focuses on health

outcomes of kidney transplantation without linking the

role of environmental, demographic and psychological/

personality factors in modifying these outcomes.

The present study has identified the contribution of

demographic factors and the need to clarify the conceptual

status of some overlapping constructs such as attitudes,

life orientation and QoL. Future studies can investigate if

there are changes in the level of optimism after the

transplant as compared to pre-transplant stage. This would

also facilitate if optimism can qualify as an attitude that

changes with life circumstances or remains stable as a

personality trait.

Personality and attitudes of the recipients need to be a

focus of the transplant team to cater for their

psychological well-being. It may facilitate tailoring

psychological management plans that could be a part of

the transplant follow-up program to enhance an optimistic

approach towards self, others and life in general.

References

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

Cowan, J. (2005). Optimism and the leisure experience. Retrieved

October 2nd 2012 from

http://lin.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/CCLR11-23.pdf.

Carver, C. S. &Scheier, M. F. (2001).Optimism, pessimism, and

self-regulation. In E. Chang (Ed.), Optimism and pessimism:

Implications for theory, research and practice (pp. 31-51).

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Calman, K.C. (1984). Quality of life in cancer patients--an

hypothesis. Journal of Medical Ethics.10 (3), 124-127.

Ferrans, C.E., & Powers, M.J. (1985). Quality of Life Index:

Development and psychometric properties, 8(1), 15-24.

Ferrans, C.E. (1990). In: Outcomes Assessment in Cancer:

Measures, Methods, and Applications. Psychometric assessment

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

of the Quality of Life Index Research in Nursing and Health 15(1),

29-38.

Ferrans, C.E. (1990). Development of a quality of life index for

patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 17, 15-19.

Ferrans, C.E., Powers, M.J. (1985). Quality of Life Index:

development and psychometric properties. Advances in Nursing

Science. 8(1), 15-24.

Ferrans, C., & Powers, M. (1992). Psychometric assessment of the

Quality of Life Index Research in Nursing Health 15(1), 29-38.

Ferrans, C.E., (1996). Development of a conceptual model of

quality of life. School Inquiry Nursing Practice 10(3), 293-304.

Fiebiger, W., Mitterbauer, C., Oberbauer, R.(2004). Health-related

quality of life outcomes after kidney transplantation Health and

Quality of Life Outcomes, 2(2).

Fisher, R.,Gould, D., Wainwright, S., & Fallon, M. (1998).

Quality of life after renal transplantation. Journal of Clinical

Nursing (7), 553-563.

Kenny, D.A. (1975). Cross-lagged panel correlation: A test for

spuriousness. Psychological Bulletin, 82(6), 887-903.

Kivimaki, M., Vahtera, J., Elovainio, M., Helenius, H., &Singh,A.

et al. (2005). Optimism and pessimism as predictors of change in

health after death or onset of severe illness in family, Health

Psychology, 24 (4), 413-421.

Lin, M.H., Chiang, Y.J., Li, C.L., & Liu, H.E. (2010).The

relationship between optimism and life Satisfaction for patients

waiting or not waiting for renal transplantation. Transplantation

Proceedings 42 (3), 763-765.

Locascio, J.J. (1982).The Cross-Lagged Correlation Technique:

Reconsideration in Terms of Exploratory Utility, Assumption

Specification and Robustness. Educational and Psychological

Measurement. 42 (4), 1023-1036.

Rogosa, D. (1980). A critique of Cross Lagged Correlation.

Psychological Bulletin 88(2), pp 249-250.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and

health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome

expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219-247.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994).

Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, selfmastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation

Test). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 10631078.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (2001). Optimism,

pessimism, and psychological well-being. In E. C. Chang (Ed.),

Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and

practice (pp. 189-216). Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association.

Smith, T. W., Pope, M. K., Rhodewalt, F., &Poulton, J. L. (1989).

Optimism, neuroticism, coping, and symptom reports: An

alternative interpretation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, (56), 640-648.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1991). Learned optimism. New York: Knopf.

Testa, M.A & Simonson, D.C. (1996). Assessment of Quality of

Life Outcomes, The New England Journal of Medicine (334), 835840.

The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment

(WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization

Social Science Medicine. 1995 Nov; 41(10):1403-9.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Lesson Plan in Curriculum DevelopmentDocument5 pagesLesson Plan in Curriculum DevelopmentJundee L. Carrillo86% (7)

- Educ 6A-Test3Document3 pagesEduc 6A-Test3Nylamezd Gnasalgam55% (11)

- Formal Peer Observation 3Document2 pagesFormal Peer Observation 3api-315857509Pas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurship & Small Business: Lecture No. 02Document20 pagesEntrepreneurship & Small Business: Lecture No. 02Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Hong Kong PHD Fellowship Scheme - Research Grants CouncilDocument5 pagesHong Kong PHD Fellowship Scheme - Research Grants CouncilMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - Modelling COVID-19 As Black SwanDocument20 pages1 - Modelling COVID-19 As Black SwanMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature NEWDocument1 pageLiterature NEWMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Ibrahim 2017Document32 pagesIbrahim 2017Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- LaevenDocument1 pageLaevenMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Steckel2016 (Hamayun SB)Document8 pagesSteckel2016 (Hamayun SB)Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Guidance NoteDocument5 pagesGuidance NoteDawod AbdiePas encore d'évaluation

- My Application For CouncilDocument2 pagesMy Application For CouncilMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Natural Disaster - Klomp2014Document36 pagesNatural Disaster - Klomp2014Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Mushtaq Hussain Khan: Mushtaq - Hussain@ajku - Edu.pk Skype Sex - Date of Birth - NationalityDocument3 pagesMushtaq Hussain Khan: Mushtaq - Hussain@ajku - Edu.pk Skype Sex - Date of Birth - NationalityMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Financing Entrepreneurship in Times of Crisis: Exploring The Impact of COVID-19 On The Market For Entrepreneurial Finance in The United KingdomDocument11 pagesFinancing Entrepreneurship in Times of Crisis: Exploring The Impact of COVID-19 On The Market For Entrepreneurial Finance in The United KingdomGianmarco David Turpo MarónPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis 00Document325 pagesAnalysis 00Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature NEWDocument1 pageLiterature NEWMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Q 1..Document4 pagesQ 1..Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Q2Document4 pagesQ2Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Formula For Panel in ExcelDocument28 pagesFormula For Panel in ExcelMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- CV - Pejman AbedifarDocument2 pagesCV - Pejman AbedifarMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Foreign Supervisor PerformaDocument2 pagesForeign Supervisor PerformaMushtaq Hussain Khan100% (3)

- Dear SirDocument3 pagesDear SirMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Tables ModifiedDocument10 pagesTables ModifiedMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Courses New Sem 2020Document3 pagesList of Courses New Sem 2020Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- SERIAL KeyDocument1 pageSERIAL KeyMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Dear SirDocument3 pagesDear SirMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- KhanDocument60 pagesKhanMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Request For Acceptance LetterDocument1 pageRequest For Acceptance LetterMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Dear SirDocument3 pagesDear SirMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Table 4Document1 pageTable 4Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Gadzo 2019Document16 pagesGadzo 2019Mushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- ManDocument1 pageManMushtaq Hussain KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Alex Lizarribar: Professional ProfileDocument2 pagesAlex Lizarribar: Professional Profileapi-247662207Pas encore d'évaluation

- Resume Sophelia McMannenDocument3 pagesResume Sophelia McMannenmcmannensPas encore d'évaluation

- A Sample of Quantitative Research Proposal Written in The APA StyleDocument16 pagesA Sample of Quantitative Research Proposal Written in The APA Styleakyar nur kholiqPas encore d'évaluation

- Ryan McDonough ResumeDocument3 pagesRyan McDonough ResumeRyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Student EmploymentDocument13 pagesStudent EmploymentbyronPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Studies Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesSocial Studies Lesson Planapi-273530753Pas encore d'évaluation

- Summative Assessment Unit Summary Sheet2Document4 pagesSummative Assessment Unit Summary Sheet2api-415881667Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dakshana JEE Faculty JDDocument1 pageDakshana JEE Faculty JDAnonymous ecgeyhVPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrated Teaching StrategiesDocument1 pageIntegrated Teaching StrategiesGan Zi XiPas encore d'évaluation

- Uwa 5e Lesson Plan GroupDocument3 pagesUwa 5e Lesson Plan Groupapi-34647295550% (2)

- Spanish Legal FrameworkDocument2 pagesSpanish Legal FrameworkOscarPas encore d'évaluation

- Garrett Daniel: EducationDocument1 pageGarrett Daniel: Educationapi-340823966Pas encore d'évaluation

- Revised-Dafielmoto, G.d.-Final ManuscriptDocument84 pagesRevised-Dafielmoto, G.d.-Final ManuscriptGracelle DafielmotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Contact Letter 14Document1 pageContact Letter 14api-233206923Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 en 148 Chapter OnlinePDFConceptsofHolisticHealthCare2016VebntegodtetalDocument8 pages1 en 148 Chapter OnlinePDFConceptsofHolisticHealthCare2016VebntegodtetalSheila ALPas encore d'évaluation

- Stattin and Kerr 2000Document14 pagesStattin and Kerr 2000green_alienPas encore d'évaluation

- Parallel Curriculum Model - AMMDocument54 pagesParallel Curriculum Model - AMMjarisco123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakaFikrah IslamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument2 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentJoji Matadling Tecson100% (1)

- Evaluasi Properti Psikometris Dan Perbandingan Model Pengukuran Konstruk Subjective Well-BeingDocument12 pagesEvaluasi Properti Psikometris Dan Perbandingan Model Pengukuran Konstruk Subjective Well-BeingRury IrawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lef030 Mapping Report WebDocument53 pagesLef030 Mapping Report WebJan WinczorekPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Unit IntroductionDocument5 pagesFinal Unit Introductionapi-271286726Pas encore d'évaluation

- Retirement HomesDocument139 pagesRetirement Homesvenkat raju0% (1)

- Lesson 7 Mental HealthDocument14 pagesLesson 7 Mental HealthRomnick BistayanPas encore d'évaluation

- English Language 1 SyllabusDocument3 pagesEnglish Language 1 Syllabusacee_mPas encore d'évaluation

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakaLinda Jeanette Angelina MontungPas encore d'évaluation

- Teacher of Physical EducationDocument4 pagesTeacher of Physical EducationChrist's SchoolPas encore d'évaluation