Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Nematode Infections in Humans, France: Trichostrongylus Colubriformis

Transféré par

Beverly FGDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Nematode Infections in Humans, France: Trichostrongylus Colubriformis

Transféré par

Beverly FGDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

LETTERS

Trichostrongylus

colubriformis

Nematode

Infections in

Humans, France

To the Editor: In April 2009, a

47-year-old woman in Saint-Jeannet

in southern France reported stomach

aches, abdominal bloating, and

occasional diarrhea. Blood analyses

found an increased eosinophil level

(8,800 cells/mm3), which represented

52% of 16,900 leukocytes/mm3.

Parasitologic examinations for

helminths were conducted with 6 fecal

specimens obtained during June 9

July 2, 2009. Analyses included direct

wet mount microscopic examination,

Merthiolateiodineformaldehyde

concentration, formalinethyl acetate

concentration, and Baermann larval

extraction.

Results of direct examination and

the Baermann technique were negative

for all samples. The formalinethyl

acetate

concentration

technique

detected a parasite egg (Figure, panel

A) and first-stage larvae. Fecal cultures

grew mature third-stage larvae (length

700800 m, 16 intestinal cells, length

of the sheath <40 m), belonging to

the genus Trichostrongylus (Figure,

panel B). Because of the ambiguous

morphologic features of this genus, a

molecular approach was necessary for

specific identification (1,2).

Identical symptoms developed

in 2 children of the patient and in 2

friends. The mother of the patient had

additional symptoms (weight loss 5

kg in 1 month and 35,000 eosinophils/

mm3, which represented 85% of

43,200 leukocytes/mm3). However,

results of fecal examinations were

negative for these 5 persons.

DNA was extracted separately

from 2 third-stage larvae (Figure,

panel B) by using the DNA Tissue Mini

Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). To

amplify internal transcribed spacer 2

(ITS2) sequences, we used primers

NC1: 5-ACGTCTGGTTCAGGGTT

GTT-3 (forward) and NC2: 5-TTAG

TTTCTTTTCCTCCGCT-3 (reverse)

(3,4), which were used by Hoste et

al. for Trichostrongylus spp. typing

(3). ITS2 rDNA was sequenced, and

third-stage larvae sequences were

registered in GenBank (accession nos.

HQ174256 and HQ174257).

Complete (100%) homology

was obtained with known sequences

(3,4) for adult Trichostrongylus

colubriformis nematodes from sheep

(GenBank accession nos. S69220,

X78063, and EF427624). Parasite

sequences also showed 100%

homology with the main haplotype

observed in humans in Laos (2).

If one considers the absence of

intraspecific variability within T.

colubriformis nematodes (3,4), the

specimens isolated from the patient

and most likely from the other 5

persons presumed to be affected in

this outbreak belong to this species.

The 6 symptomatic patients

were treated according to published

recommendations

(5)

with

albendazole, 400 mg/day for 10 days.

Clinical remission was obtained in <3

days, and eosinophil counts returned

to reference levels 3 months later.

Specific questioning of the 6

persons indicated that the source

of infection most likely was a meal

eaten in April 2009, which included

strawberries picked in the vegetable

garden of the patients mother. The

patients father and brother did not eat

any strawberries and did not have any

symptoms. The garden was fertilized

yearly with dried manure from a local

sheep farm. Lack of dried manure in

2009 led to use of fresh sheep manure

from the same farm. Sheep manure

from breeding stock on the farm was

examined. Trichostrongylus spp.

third-stage larvae were found despite

prophylactic treatment of sheep on the

farm against helminths.

T.

colubriformis

nematodes

are mainly parasites of herbivorous

mammals and have a worldwide

distribution. Human infections are

found predominantly in warm areas.

They are usually asymptomatic or

as described in the present case.

T. colubriformis adults live in the

intestines of the host (6). The female

lays eggs, which are excreted in feces.

Eggs then hatch and mature into

infectious larvae. Humans become

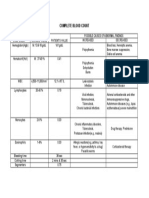

Figure. Trichostrongylus colubriformis nematode isolated from feces of a 47-year-old woman,

France. A) Egg (length 89 m) isolated by using direct examination (original magnification

200). B) Third-stage larvae (length 740 m, 16 intestinal cells, length of distal part of the

sheath <40 m) isolated by using fecal culture (original magnification 50). A color version

of this figure is available online (www.cdc.gov/EID/content/17/7/1301-F.htm).

Emerging Infectious Diseases www.cdc.gov/eid Vol. 17, No. 7, July 2011

1301

LETTERS

infected by ingesting unwashed

vegetables contaminated by animal

feces containing strongyloid larvae.

Larvae mature into adults in the

intestines.

Sporadic cases of this infection

in humans have been reported in

many countries (7). In France,

several autochthonous cases were

suspected, but because of their rarity

and difficulty in identification, they

are not commonly reported (8). Eggs

of Trichostrongylus spp. can be

differentiated from those of Necator

and Ancylostoma spp. because they are

longer, narrower, and elongated. After

6 days of culture, T. colubriformis

nematodes can be distinguished from

similar stages in Strongyloides and

Ancylostoma spp. by the bead-like

swelling at the tip of the tail. Except

for isolation of adult worms, which

are rarely found in feces, sequencing

of the ITS2 region is the most accurate

method for specific identification of

Trichostrongylus spp. isolated from

humans.

This familial outbreak highlights

increased risk for animal parasitosis in

humans in an industrialized country,

which may have been caused by an

increasing trend of persons using

ecologic and organic farming methods.

These cases confirm that hygienic

recommendations for use of organic

fertilizer must be disseminated on a

large scale. It is also mandatory that

fresh vegetables be washed carefully

and thoroughly before ingestion, and

only dried manure should be used as

an organic fertilizer.

Stphanie Latts, Hubert Fert,

Pascal Delaunay,

Jrme Depaquit,

Matteo Vassallo, Mlanie Vittier,

Sahare Kokcha, Eric Coulibaly,

and Pierre Marty

Author affiliations: Centre Hospitalier

Universitaire de Nice, Nice, France (S.

Latts, P. Delaunay, M. Vassallo, S. Kochka);

Universit de Reims ChampagneArdenne,

Reims, France (H. Fert, J. Depaquit, M.

1302

Vittier); Services Vtrinaires des AlpesMaritimes, Sophia-Antipolis, France (E.

Coulibaly); and Universit de NiceSophia

AntipolisInserm 0895, Nice (P. Marty)

DOI: 10.3201/eid1707.101519

References

1. Yong TS, Lee JH, Sim S, Lee J, Min DY,

Chai JY, et al. Differential diagnosis of

Trichostrongylus and hookworm eggs

via PCR using ITS-1 sequence. Korean

J Parasitol. 2007;45:6974. doi:10.3347/

kjp.2007.45.1.69

2. Sato M, Sanguankiat S, Yoonuan T,

Pongvongsa T, Keomoungkhoun M,

Phimmayoi I, et al. Copro-molecular

identification of infections with hookworm eggs in rural Lao PDR. Trans R

Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:61722.

doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.06.006

3. Hoste H, Chilton NB, Gasser RB, Beveridge I. Differences in the second internal transcribed spacer (ribosomal DNA)

between five species of Trichostrongylus

(Nematoda: Trichostrongylidae). Int J Parasitol. 1995;25:7580. doi:10.1016/00207519(94)00085-3

4. Hoste H, Gasser RB, Chilton NB, Mallet S, Beveridge I. Lack of intraspecific

variation in the second internal transcribed

spacer (ITS-2) of Trichostrongylus colubriformis ribosomal DNA. Int J Parasitol.

1993;23:106971.

doi:10.1016/00207519(93)90128-L

5. Ghadirian E. Human infection with

Trichostrongylus lerouxi (Biocca, Chabaud, and Ghadirian, 1974) in Iran. Am J

Trop Med Hyg. 1977;26:12123.

6. Boreham RE, McCowan MJ, Ryan

AE, Allworth AM, Robson JM. Human

trichostrongyliasis in Queensland. Pathology. 1995;27:1825. doi:10.1080/

00313029500169842

7. Gutierrez Y, Guerrant RL, Walker DH,

Weller PF. Other tissue nematode infections. In: Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller

PF, editors. Tropical infectious diseases,

principles, pathogens and practice. 2nd

ed. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.

p. 123147.

8. Thibert J-B, Guiguen C, Gangneux J-P.

Human trichostrongyloidosis: case report

and microscopic difficulties to identify ankylostomidae eggs. Ann Biol Clin (Paris).

2006;64:2815.

Address for correspondence: Pascal Delaunay,

ParasitologieMycologie, Centre Hospitalier

Universitaire lArchet, BP 3079, 06202 Nice

Cedex 3, France; email: delaunay.p@chu-nice.

fr

Adult Opisthorchis

viverrini Flukes in

Humans, Takeo,

Cambodia

To the Editor: Opisthorchis

viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis, the

2 major species of small liver flukes

(family

Opisthorchiidae),

cause

chronic inflammation in the bile duct,

which leads to cholangitis and cirrhosis

of the liver, and are a predisposing

factor for cholangiocarcinoma (1).

Human infections with O. viverrini

flukes are found along riverside areas

of Indochina (Thailand, Lao Peoples

Democratic Republic [PDR], and

Vietnam) (2).

Small trematode eggs (length

2032 m) have been found in human

fecal samples in Cambodia (1,3,4).

During 19811982, two of 102

Cambodian refugees in the United

States were found to be positive for C.

sinensis (likely O. viverrini) eggs (3).

Egg-positive cases were later detected

in several provinces of Cambodia

(4,5). Presence of O. viverrini flukes

in Cambodia was verified by detection

of metacercariae in freshwater fish in a

lake on the border between Takeo and

Kandal Provinces and by isolation of

adult flukes in experimentally infected

hamsters (6).

In May 2010, we analyzed fecal

samples from 1,993 persons in 3

villages (Ang Svay Chek, Kaw Poang,

and Trartang Ang) in the Prey Kabas

District, Takeo Province, Cambodia,

45 km south of Phnom Penh, to

confirm the presence of O. viverrini

flukes among humans. We found an

egg-positive rate of 32.4% for small

trematode eggs. Because these eggs

may be those of Haplorchis spp.

flukes (H. taichui, H. pumilio, and

H. yokogawai) and lecithodendriid

flukes (Prosthodendrium molenkampi

and Phaneropsolus bonnei) (1), we

attempted to detect adult flukes that

are responsible for these eggs.

Emerging Infectious Diseases www.cdc.gov/eid Vol. 17, No. 7, July 2011

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Viverrini Flukes In: Adult Opisthorchis Humans, Takeo, CambodiaDocument3 pagesViverrini Flukes In: Adult Opisthorchis Humans, Takeo, CambodiaAvivhYoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fate of Entamoeba Histolytica During Establishment of Amoebic Liver Abscess Analyzed by Quantitative Radioimaging and HistologyDocument8 pagesFate of Entamoeba Histolytica During Establishment of Amoebic Liver Abscess Analyzed by Quantitative Radioimaging and HistologyMaithreyanNandhakumarPas encore d'évaluation

- High Prevalence of Human Liver Infection by Flukes, Ecuador: Amphimerus SPPDocument4 pagesHigh Prevalence of Human Liver Infection by Flukes, Ecuador: Amphimerus SPPMigue LitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Adehan Et Al A.phagocytophilum - Eyinka - 3Document29 pagesAdehan Et Al A.phagocytophilum - Eyinka - 3garmelmichelPas encore d'évaluation

- Jir 409Document10 pagesJir 409utkarsh PromotiomPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0167701218306821 Main PDFDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0167701218306821 Main PDFDiego TulcanPas encore d'évaluation

- Molecular Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in Humans and Cattle in The NetherlandsDocument9 pagesMolecular Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in Humans and Cattle in The NetherlandsasfasdfadsPas encore d'évaluation

- Schär2014Document7 pagesSchär2014KuyinPas encore d'évaluation

- Feline Panleukopenia Virus Infection in Various Species From HungaryDocument9 pagesFeline Panleukopenia Virus Infection in Various Species From HungaryAlonSultanPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 2 BRDocument3 pages1 2 BRrahmani bagherPas encore d'évaluation

- 1211-Article Text-4315-3-10-20200101Document4 pages1211-Article Text-4315-3-10-20200101nasywaPas encore d'évaluation

- Brachyotis) in Ketapang Timur Village, Ketapang Sub-District, SampangDocument6 pagesBrachyotis) in Ketapang Timur Village, Ketapang Sub-District, SampangrabiatulfajriPas encore d'évaluation

- E. Coli UTIDocument9 pagesE. Coli UTIJaicé AlalunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Staphylococci From Clinical Sources Recovered From InfantsDocument7 pagesAntibiotic Resistance Profile of Staphylococci From Clinical Sources Recovered From InfantsCornius TerranovaPas encore d'évaluation

- Feline Gastrointestinal Eosinofílica Fibroplasia EsclerosanteDocument8 pagesFeline Gastrointestinal Eosinofílica Fibroplasia EsclerosanteCarlos Alberto Chaves VelasquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Article Salmonella SPP., Clostridium Perfringens, and C. DifficileDocument10 pagesResearch Article Salmonella SPP., Clostridium Perfringens, and C. DifficileTheresa Tyra SertaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Fecalysis PDFDocument9 pagesFecalysis PDFAllaine Garcia100% (1)

- Bacterial Enteritis in Ostrich Struthio Camelus CHDocument7 pagesBacterial Enteritis in Ostrich Struthio Camelus CHali hendyPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0168160516303919 Main PDFDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0168160516303919 Main PDFDiego TulcanPas encore d'évaluation

- Prevalence of Yersinia EnterocoliticaDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Yersinia EnterocoliticaLorenza Khurotayun TjahyapasaPas encore d'évaluation

- Parasitos en ReptilesDocument13 pagesParasitos en ReptilesEduardo Pella100% (1)

- Gordon2015-Multiplex Real-Time PCR Monitoring of Intestinal Helminths in HumansDocument7 pagesGordon2015-Multiplex Real-Time PCR Monitoring of Intestinal Helminths in HumanswiwienPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0740002017304409 Main PDFDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0740002017304409 Main PDFDIEGO FERNANDO TULCAN SILVAPas encore d'évaluation

- Et Al. - On The Origin of LeprosyDocument15 pagesEt Al. - On The Origin of LeprosyRoberto SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Danet Et All (2011)Document13 pagesDanet Et All (2011)Camila GamboaPas encore d'évaluation

- Allen 2002 Recent Advances in Biology and Immunobiology of Eimeria Species and in Diagnosis and Control of InfectionDocument8 pagesAllen 2002 Recent Advances in Biology and Immunobiology of Eimeria Species and in Diagnosis and Control of InfectionRicardo Alberto Mejia OspinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prevalence of Urinary Schistosomiasis in Ahomey-Lokpo, Commune of So-Ava, Benin RepublicDocument7 pagesPrevalence of Urinary Schistosomiasis in Ahomey-Lokpo, Commune of So-Ava, Benin RepublicOpenaccess Research paperPas encore d'évaluation

- Temperature Dependence of Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection in First Intermediate Host Snail, Bithynia Siamensis GoniomphalosDocument6 pagesTemperature Dependence of Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection in First Intermediate Host Snail, Bithynia Siamensis Goniomphalossetriany listarinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Enfermedades Por Protozoos Criptosporidiosis, Giardiasis y Otras Enfermedades Por Protozoos IntestinalesDocument18 pagesEnfermedades Por Protozoos Criptosporidiosis, Giardiasis y Otras Enfermedades Por Protozoos IntestinalesCarol VelezPas encore d'évaluation

- Regulatory T Cells in Mouse Periapical LesionsDocument5 pagesRegulatory T Cells in Mouse Periapical LesionsEnrique DíazPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0740002016304555 Main PDFDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0740002016304555 Main PDFDIEGO FERNANDO TULCAN SILVAPas encore d'évaluation

- Disentri AmubaDocument8 pagesDisentri AmubaVivi DeviyanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of Three Antigenic Extracts of Eurotium Amstelodami in Serological Diagnosis of Farmer's Lung DiseaseDocument8 pagesComparison of Three Antigenic Extracts of Eurotium Amstelodami in Serological Diagnosis of Farmer's Lung DiseaseFatwa MPas encore d'évaluation

- Feline Plasma Cell Pododermatitis - A Study of 8 Cases (Pages 333-337)Document5 pagesFeline Plasma Cell Pododermatitis - A Study of 8 Cases (Pages 333-337)jenPas encore d'évaluation

- Detection of Cryptosporidium Spp. in Calves by Using A Acid Fast Method and Confirmed by Immunochromatographic and Molecular AssaysDocument6 pagesDetection of Cryptosporidium Spp. in Calves by Using A Acid Fast Method and Confirmed by Immunochromatographic and Molecular AssaysFabian DelgadoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Zoonotic Importance of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Transmission From Human To MonkeyDocument2 pagesThe Zoonotic Importance of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Transmission From Human To MonkeyFelipe Guajardo HeitzerPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Methods For Demonstration: Study of Tissue Culture of Toxoplasma GondiiDocument4 pagesComparative Methods For Demonstration: Study of Tissue Culture of Toxoplasma GondiiSalim JufriPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal PNTD 0010062Document18 pagesJournal PNTD 0010062adinda larasPas encore d'évaluation

- Entamoeba Coli & HistolyticaDocument15 pagesEntamoeba Coli & HistolyticaImasari AryaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Pyrethroid Resistance in An Population From Uganda: Anopheles FunestusDocument8 pagesPyrethroid Resistance in An Population From Uganda: Anopheles Funestusibrahima1968Pas encore d'évaluation

- Articulo 3Document5 pagesArticulo 3Valeria Rodriguez GomezPas encore d'évaluation

- Histomonas MeleagridisDocument7 pagesHistomonas MeleagridisGabriela Pereyra FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Hongos PerroDocument4 pagesHongos PerroHelen Dellepiane GilPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 3 - Article - Diagnosis of Eimeria Species Using Traditional and Molecular Methods in Field StudiesDocument6 pagesGroup 3 - Article - Diagnosis of Eimeria Species Using Traditional and Molecular Methods in Field StudiesKashmir LallaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prevalence of Gastrointestinal ParasitesDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Gastrointestinal ParasitesdharnfestusbPas encore d'évaluation

- Molecular Characterization of Extended-Spectrum BetaLactamase (ESBLs) Genes in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa From Pregnant Women Attending A Tertiary Health Care Centre in Makurdi, Central NigeriaDocument7 pagesMolecular Characterization of Extended-Spectrum BetaLactamase (ESBLs) Genes in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa From Pregnant Women Attending A Tertiary Health Care Centre in Makurdi, Central NigeriaJASH MATHEWPas encore d'évaluation

- The Intestinal Protozoa: A. IntroductionDocument32 pagesThe Intestinal Protozoa: A. Introductionهاني عقيل حسين جوادPas encore d'évaluation

- ISSN (Print) 0023-4001 ISSN (Online) 1738-0006Document6 pagesISSN (Print) 0023-4001 ISSN (Online) 1738-0006WIODI NAZHOFATUNNISA UMAMI SWPas encore d'évaluation

- AdenoDocument4 pagesAdenoJulio BarriosPas encore d'évaluation

- Dioctophyma Renale in A Dog: Clinical Diagnosis and Surgical TreatmentDocument6 pagesDioctophyma Renale in A Dog: Clinical Diagnosis and Surgical Treatmentkuldeep sainiPas encore d'évaluation

- Paper RespiratorioDocument8 pagesPaper RespiratorioDave IgnacioPas encore d'évaluation

- Fenotipos Bioquímicos y Fagotipos de Cepas de Salmonella Enteritidis Aisladas en Antofagasta, 1997-2000Document9 pagesFenotipos Bioquímicos y Fagotipos de Cepas de Salmonella Enteritidis Aisladas en Antofagasta, 1997-2000axel vargasPas encore d'évaluation

- ABSTRACT. Blood Protozoan Diseases: M J V RDocument15 pagesABSTRACT. Blood Protozoan Diseases: M J V RNiluh dewi KustiantariPas encore d'évaluation

- Differentiation of Trichinella Species (Trichinella Spiralis/trichinella Britovi Versus Trichinella Pseudospiralis) Using Western BlotDocument11 pagesDifferentiation of Trichinella Species (Trichinella Spiralis/trichinella Britovi Versus Trichinella Pseudospiralis) Using Western BlotAdina AnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gamberini Et AlDocument9 pagesGamberini Et AlDeboraXiningPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dangers of Diasease Transmission by Artificial Insemination and Embryo TransferDocument31 pagesThe Dangers of Diasease Transmission by Artificial Insemination and Embryo TransferLAURA DANIELA VERA BELTRANPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Considerations On Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis in Greece: A Retrospective Study of 158 Cases (1989-1996)Document8 pagesClinical Considerations On Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis in Greece: A Retrospective Study of 158 Cases (1989-1996)5-Mint PUBGPas encore d'évaluation

- PHILJA Bulletin NO.69Document48 pagesPHILJA Bulletin NO.69Beverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Bul66 PDFDocument48 pagesBul66 PDFBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Bul65 PDFDocument44 pagesBul65 PDFBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Bulletin 67 PHILJADocument32 pagesBulletin 67 PHILJABeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- PHILJA Bulletin 64Document24 pagesPHILJA Bulletin 64Beverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual For Clerk of Courts PhilippinesDocument3 pagesManual For Clerk of Courts PhilippinesBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual For Clerk of Courts PhilippinesDocument23 pagesManual For Clerk of Courts PhilippinesBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Pascual vs. Secretary of Public Works, 110 Phil 331Document3 pagesPascual vs. Secretary of Public Works, 110 Phil 331Beverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- PNP Ethical DoctrineDocument23 pagesPNP Ethical DoctrineBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Bunkhouse RuleDocument1 pageBunkhouse RuleBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- ChordsDocument1 pageChordsBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual Clerk of Court PhilippinesDocument15 pagesManual Clerk of Court PhilippinesBeverly FG100% (1)

- Benjamin Yu Vs NLRC and Rojas Vs Maglana Case DigestsDocument4 pagesBenjamin Yu Vs NLRC and Rojas Vs Maglana Case DigestsBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Forms of Escape From TaxationDocument3 pagesForms of Escape From TaxationBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases On Wills and SuccessionDocument4 pagesCases On Wills and SuccessionDeb BagaporoPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviewer SuccessionDocument34 pagesReviewer SuccessionBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Forensic Request FormatsDocument22 pagesForensic Request FormatsBeverly FG100% (2)

- Labor Code 2nd ReportDocument13 pagesLabor Code 2nd ReportBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample of Application For Search WarrantDocument3 pagesSample of Application For Search WarrantBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Oxygen Therapy AssignmentDocument2 pagesOxygen Therapy AssignmentBeverly FG0% (1)

- 2009 Bar Examination QuestionDocument25 pages2009 Bar Examination QuestionBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Complete Blood CountDocument1 pageComplete Blood CountBeverly FGPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding The Self Activity 3Document7 pagesUnderstanding The Self Activity 3Enrique B. Picardal Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- CHP 11 Moderate Nonskeletal Problems in Preadolescent ChildrenDocument6 pagesCHP 11 Moderate Nonskeletal Problems in Preadolescent ChildrenJack Pai33% (3)

- Mommy's MedicineDocument3 pagesMommy's Medicinekcs.crimsonfoxPas encore d'évaluation

- Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria For Kawasaki DiseaseDocument2 pagesTable 1. Diagnostic Criteria For Kawasaki DiseasenasibdinPas encore d'évaluation

- Pharmacology Book - PharmaceuticsDocument48 pagesPharmacology Book - PharmaceuticsRuchi SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Surgical Correction Subglottic Stenosis of The Larynx: AnnoldDocument6 pagesSurgical Correction Subglottic Stenosis of The Larynx: Annoldcanndy202Pas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study 25Document3 pagesCase Study 25Desiree Ladner Scott86% (7)

- Negatil Tablet: What Is in This LeafletDocument2 pagesNegatil Tablet: What Is in This LeafletEe JoPas encore d'évaluation

- CELECOXIBDocument1 pageCELECOXIBRicky Ramos Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Iv Therapy LecDocument11 pages5 Iv Therapy LecSofia LozanoPas encore d'évaluation

- OT HoppysAppReviewDocument1 pageOT HoppysAppReviewIris De La CalzadaPas encore d'évaluation

- An Introduction To NutritionDocument17 pagesAn Introduction To NutritionAlejandra Diaz RojasPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.8.2 HandoutDocument4 pages1.8.2 Handoutkhushisarfraz123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bioplan Nieto Nahum)Document6 pagesBioplan Nieto Nahum)Claudia Morales UlloaPas encore d'évaluation

- Autoimmune Mash - Up FinalDocument38 pagesAutoimmune Mash - Up Finalapi-546809761Pas encore d'évaluation

- Marine-Derived Pharmaceuticals - Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument11 pagesMarine-Derived Pharmaceuticals - Challenges and OpportunitiesElda ErnawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Raasn October NewsletterDocument6 pagesRaasn October Newsletterapi-231055558Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sample ExamDocument13 pagesSample ExamJenny Mendoza VillagonzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter II - Bodies of Fire - The Accupuncture MeridiansDocument41 pagesChapter II - Bodies of Fire - The Accupuncture MeridiansScott Canter100% (1)

- Cancer Fighting StrategiesDocument6 pagesCancer Fighting StrategiesDahneel RehfahelPas encore d'évaluation

- Healthy LivingDocument57 pagesHealthy LivingGrover DejucosPas encore d'évaluation

- Home Remedies Using Onion Prophet666Document2 pagesHome Remedies Using Onion Prophet666Hussainz AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Uniformity of Dosage UnitsDocument5 pagesUniformity of Dosage UnitsJai MurugeshPas encore d'évaluation

- Tumoret e VeshkaveDocument118 pagesTumoret e VeshkavealpePas encore d'évaluation

- AcetanilideDocument4 pagesAcetanilideJinseong ChoiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Antimicrobial ActivitiesDocument4 pagesThe Antimicrobial ActivitiesromalfioPas encore d'évaluation

- QUIZ Classification of Surgery in TableDocument1 pageQUIZ Classification of Surgery in TableMaria Sheila BelzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Electron Beam Therapy PhysicsDocument36 pagesReview of Electron Beam Therapy PhysicsMaría José Sánchez LovellPas encore d'évaluation

- Pga 2014 ProspectusDocument31 pagesPga 2014 ProspectusKaranGargPas encore d'évaluation