Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Icft05i1p3 PDF

Transféré par

Anjum ShakeelaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Icft05i1p3 PDF

Transféré par

Anjum ShakeelaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Indian Journal of Neurotrauma (IJNT)3

2005, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 3-6

Review Article

Current Management of Odontoid Fractures

Awadhesh Kumar Jaiswal M Ch, Manish S Sharma M Ch, Sanjay Behari M Ch

Bernard T. Lyngdoh M Ch, Subodh Jain M Ch, Vijendra K. Jain M Ch

Department of Neurosurgery

Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow 226014

Abstract: Odontoid fracture frequently occurs following cervical trauma. As C1-2 vertebral level

allows

the maximum motion in the cervical spine, these fractures may often be unstable, causing catastrophic

spinal cord trauma and respiratory compromise. In this article, the current management of odontoid

fractures is reviewed.

Keywords: cervical spine injury, odontoid fracture, odontoid process

INTRODUCTION AND CLASSIFICATION

Off all the cases of cervical trauma, about one out of five

involves the axis1. The commonest type of the axis injury is

an odontoid fracture at the junction of the dens and the

body (type II odontoid fracture)2.

The C1-2 complex allows far more motion than any other

single level in the cervical spine. This motion is

predominantly rotational, since translational motion at C1C2 is limited by the strong transverse ligament. This

restriction is lost after fracture of the odontoid and may be

associated with antero- or retrolisthesis of the C1-C2

complex in relation to the C2 body. This may result in spinal

cord compression producing severe neurological deficits3.

associated with posterior displacement of the C1 archfragment relative to the body of axis5.

FIGURE 1: Diagrams showing a) the transverse ligament supporting

the dens to the C1 arch; and, b) the cruciate ligament supporting

the occipito-atlanto-axial complex

Anderson and D Alonzo2 classified dens fracture into

three types:

Type I- involves the tip of the odontoid process. This is the

least common type of odontoid fracture.

Type II- is the commonest type of dens fracture. The fracture

line involves the junction of the body of dens with the

body of axis. Sometimes type II fracture is associated with

a comminuted fragment at the base of dens called the type

II A variety of fracture. This fracture is markedly unstable4.

Type III- The fracture line involves the body of C2 in

addition to passing through dens.

The commonest cause of dens fracture is hyperflexion

at the neck. This may lead to an anterior displacement of

C1 on C2 (atlanto-axial subluxation). Extension only

occasionally produces odontoid fracture and this is usually

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sanjay Behari, MCh, DNB

Associate Professor, Department of Neurosurgery, Sanjay Gandhi

Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow 226014,

E mail: sbehari27@yahoo.com; sbehari@sgpgi.ac.in, Fax: 91-5222668017, 2668078

FIGURE 2: Diagrams showing a) the type I; b) type II; and, c) type

III odontoid fractures

Indian Journal of Neurotrauma (IJNT), Vol. 2, No. 1, 2005

Awadhesh Kumar Jaiswal, Manish S Sharma, Sanjay Behari

Bernard T. Lyngdoh, Subodh Jain, Vijendra K. Jain

FIGURE 3. Coronal CT scan showing a) type II; and, b) type III

odontoid fractures

CLINICAL FEATURES

Patients with acute dens fractures usually present with

upper cervical pain and restriction of neck movements.

They may have a tendency to support their head with their

hands while moving from an upright to a supine position.

In case of cord compression by the displaced fracture

segments, cervical myelopathy may occur. In a study, 82%

patients of type II fractures presented with intact

neurological status; 8% had minimal sensory disturbances

over the scalp or limb; and 10% had significant neurological

deficits. Type I and type III odontoid fractures are rarely

associated with neurological deficits6. About 25-40% of

dens fractures are fatal at the time of accident.

MANAGEMENT

fracture odontoid treated with external immobilization alone.

Hadley4 described that type II A dens fractures have a very

high tendency of non-union. The current role of external

immobilization in case of type II dens fractures is where

patients are unfit for general anesthesia or they have

sustained severe concurrent injury that precludes primary

surgical intervention for the fractured odontoid. Apfelbaum

et al17 have found a lower rate of bony fusion in patients

with anterior oblique fractures when compared to patients

in whom posterior oblique or horizontal fractures were

demonstrated.

FIGURE 4. Sagittal MR scan showing an atlantoaxial dislocation

due to type II odontoid fracture

Surgical treatment

Type I odontoid fractures

Anterior approach

Most neurosurgeons agree that these fractures are

generally stable and can be managed with external

immobilization using a hard cervical collar. There is very

low incidence of non-union, and surgery is seldom

indicated for these fractures2,7.

Anterior odontoid screw fixation was first reported by

Nakanishi 18 and Bohler 19 . This procedure provides

immediate spinal stability, preserves the normal rotation

between C1-2, allows the best anatomical and functional

outcome for type II odontoid fracture, and is associated

with rapid patient mobilization, minimal postoperative pain

and a short hospital stay. Acute odontoid fractures treated

by anterior screw fixation have a fusion rate of approximately

90 percent20.

Type II odontoid fractures

Conservative treatment

In the management of type II odontoid fractures, longenduring controversies exist: Should conservative

management with halo immobilization be adopted; or, should

surgical reduction and fusion be undertaken? In case of

the latter, should the approach be anterior or posterior?

Studies utilizing external immobilization have reported a

wide-ranging result8-15 varying from ineffectualness14 to

93 percent15 success. Various factors affecting the rate of

union of fractured odontoid include elderly age, degree of

dens displacement, presence of concomitant C1-2 fracture,

pre-existing pathological condition and age of the fracture16.

Apuzzo et al8 reported that dens displacement exceeding

4mm and an age above 40 years are associated with 88%

chance of non-union of fracture odontoid treated with

external immobilization alone. Dunn et al12 reported that

age greater than 65 years along with retrolisthesis

correlated with about 70-78% chance of non-union of

Indian Journal of Neurotrauma (IJNT), Vol. 2, No. 1, 2005

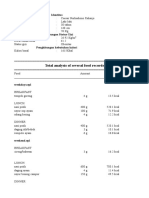

Table 1: Surgical approaches for odontoid fracture

Anterior approach

Anterior odontoid screw fixation

Single screw

Multiple screw

Posterior approach

C1-2 sublaminer wire fixation and bone grafting

Gallies method

Brooks method

Sonntags method

Posterior C1-2 transarticular screw fixation

Magerls procedure

Magerls procedure supplemented with

C1-2 sublaminar wire fixation

Jains method of creating artificial arch on the

occipital bone with sublaminar wiring

Ransfords contoured rod fixation

Current Management of Odontoid Fractures

In the anterior screw fixation procedure, one or more

screws may be used. Earlier studies emphasized on the

concept of multiple screw usage for type II odontoid

fractures mentioning that multiple screws augment the

structural strength of the fusion and prevent the rotation

of odontoid on the body of C221,22. Recent studies found

no significant difference in the fusion rate in the patients

treated with single or two odontoid screws23.

Various types of screws are available, including cortical

or cancellous bone screws, self-tapping or non self-tapping

screws, lag screws or cannulated screws, and, fully or

partially threaded screws. Partially threaded lag screws are

commonly used for fixating the odontoid. Lag compression

helps to unite the fracture line by producing a compressive

force. This helps in coupling the fractured fragments in

addition to providing rigid fixation. Non self- tapping screws

provide stronger screw purchase in the bone than self

tapping screws16.

The anterior odontoid screw fixation has certain

limitations. Surgery requires adequate high cervical

exposure and soft tissue retraction, which create anatomical

limitations, as does the inability to add graft material to

enhance fusion stability. Patients with short neck and barrelshaped chest may not be suitable surgical candidates for

the anterior approach because their anatomy interferes with

an appropriate screw trajectory. A prerequisite for anterior

screw fixation is an intact transverse ligament and a

horizontal fracture line, which may not always be the case.

In cases of chronic odontoid fracture, anterior screw fixation

is associated with a high chance of non-union. The anterior

screw fixation for odontoid fracture should be only

performed when the fractured odontoid and the remaining

C2 body are adequately aligned prior to screw insertion16.

Posterior approach

Posterior approach for stabilization of odontoid fracture is

indicated in the cases of odontoid fracture that are not

amenable to anterior screw fixation. Commonly used

procedures involve wedging a bone graft between posterior

arch of C1 and the C2 lamina with sublaminar wiring. The

well-described different methods for this C1- 2 posterior

fusion procedure are the Gallie24, Brooks25, Sonntag26

techniques. These procedures have a satisfactory fusion

rate of about 74 percent20. The demerit of this procedure is

that it causes elimination of the normal C1-2 rotatory motion

( which accounts for more than 50% of all cervical spine

rotatory movements) and reduced cervical spine flexion

extension by 10 percent21.

Another excellent alternative technique for odontoid

fracture is the posterior C1-2 transarticular screw fixation

(Magerls procedure) using unilateral or bilateral screws27,28.

This provides an excellent spinal rotational spinal stability.

This is an indirect method of stabilizing the fracture (in

which the normal anatomical configuration is disrupted).

Preoperative CT evaluation is mandatory to avoid vertebral

artery injury in this procedure. This technique can be

supplemented with metal plate for occipito-cervical

stabilization. Alternatively, Jains technique of

occipitocervical fusion29, Goels plate and screw lateral mass

fixation30, or a Ransfords contoured rod technique31 may

be utilized.

Type III odontoid fracture

Conservative treatment

For type III odontoid fractures, external immobilization is a

successful treatment option. Various studies have reported

about 85% fusion rate for type III dens fractures treated by

external immobilization2,7. Age was not clearly a predictor

of successful fusion. The degree of fracture displacement

had a negative correlation in few studies. About 97% fusion

rate has been demonstrated in cases of type III dens fracture

treated with posterior cervical fixation methods and almost

100% fusion rate has been shown by anterior screw

fixation20.

CONCLUSIONS

For type I and type III dens fractures, external

immobilization provides a satisfactory fusion rate of almost

100% and 84% respectively. However, anterior screw fixation

for type III dens fractures improves the fusion rate to nearly

100%. For type II odontoid fractures, the role of external

immobilization is limited to only select cases who are not fit

for a surgical procedure as it provides a fusion rate of

approximately 65%. Anterior screw or posterior cervical

stabilization procedures provide a 74 to 90% fusion rate.

The former is preferred in acute Type II fractures due to its

ability to preserve C1-C2 axial rotation but cannot be applied

in cases of transverse ligament disruption, significantly

displaced fractured segment or with communited fractures.

REFERENCES

1.

Huelke DF, ODay J, Mendelson RA. Cervical injuries suffered

in automobile crashes.

J Neurosurg 1989; 54: 316-22

2.

Anderson LD, DAlonzo RT. Fractures of the odontoid process

of the axis.

J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1974; 56: 1663-74.

3.

White AA III, Panjabi MM. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine,

ed 2. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1990, pp 92-7.

4.

Hadley MN, Browner CM, Liu SS et al New subtype of acute

odontoid fracture (type II A).

Neurosurgery 1988; 22: 67-71.

Indian Journal of Neurotrauma (IJNT), Vol. 2, No. 1, 2005

Awadhesh Kumar Jaiswal, Manish S Sharma, Sanjay Behari

Bernard T. Lyngdoh, Subodh Jain, Vijendra K. Jain

5.

Stillerman CB, Roy RS, Weis MH. Cervical spine injuries:

Diagnosis and treatment. In Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS (eds)

Neurosurgery Vol II, ed 2. 2875-2904.

6.

Przybylski GJ. Management of odontoid fractures.

Contemp Neurosurg 1998; 20: 1-6.

7.

Hadley MN, Bishop RC. Injuries of the craniocervical junction

and upper cervical spine, in Tindall GT, Cooper PR, Barrow

DL (eds): The Practice of Neurosurgery. Baltimore: Williams

and Wilkins, 1996; 2: 1687-701.

8.

Apuzzo MLJ, Heiden JS, Weiss MH et al, et al. Acute fracture

of the odontoid process. An analysis of 45 cases.

J Neurosurg 1978;48: 85-91.

9.

Fujii E, Kobayashi K, Hirabayashi K. Treatment in the fractures

of the odontoid process.

Spine 1988; 13: 604-609.

10. Schatzker J, Rorabeck CH, Waddell JP. Fracture of the dens

(odontoid process). Analysis of thirty-seven cases.

J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1971; 53: 392-405.

11. Hadley MN, Browner C, Sonntag VKH. Axis fractures: a

comprehensive review of management and treatment in 107 cases.

Neurosurgery 1985; 17: 281-90.

12. Dunn ME, Seljeskog EL. Experience in the management of

odontoid process injuries: an analysis of 128 cases.

Neurosurgery 1986; 18: 306-10

13. Wang GJ, Mabie KN, Whitehill R et al. The nonsurgical

management of odontoid fracture in adults.

Spine 1984; 9: 229-30.

14. Maiman DJ, Larson SJ. Management of odontoid fractures.

Neurosurgery 1982; 11: 471-6.

unions of the dens.

J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1982; 64: 18-27.

20. Julien TD, Frankel B, Traynelis VC, Ryken TC. Evidencebased analysis of odontoid fracture management.

Neurosurg Focus 2000; 8: 1-6.

21. Apfelbaum RI: Anterior screw fixation of odontoid fractures,

in Camins MB, OLeary PF (eds): Diseases of the cervical

spine. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1992, pp 603-8.

22. Geisler FH, Cheng C, Poka A et al. Anterior screw fixation of

posteriorly displaced Type II odontoid odontoid fractures.

Neurosurgery 1989; 25: 34-8.

23. Jenkins JD, Coric D, Branch CL Jr. a clinical comparison of

one and two screw odontoid fixation.

J Neurosurg 1998; 89: 366-70.

24. Gallie WE. Fractures and dislocations of the cervical spine.

Am J Surg 1939; 46: 495-9.

25. Brooks Al, Jenkins EB. Atlanto-axial arthrodesis by the wedge

compression method.

J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1978; 60:279-284

26. Dickman CA, Sonntag VKH, Papadopoulos SM et al. The

interspinous method of posterior atlantoaxial arthrodesis.

J Neurosurg 1991; 74: 190-8.

27. Jeanneret B, Magerl F. Primary posterior fusion of C1/2 in

odontoid fractures: indication, technique, and result of transarticular screw fixation.

J Spinal Disord 1992; 5: 464-75.

28. Magrel F, Seemann PS. Stable posterior fusion of the atlas and

axis by transarticular screw fixation, in Weidner PA (ed):

Cervical Spine. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1987, Vol 1, 322-7.

15. Lind B, Nordwall A, Sihlbom H. Odontoid fracture treated with

halo-vest.

Spine 1987; 12: 173-7.

29. Jain VK, Behari S. Posterior occipitoaxial fusion for

atlantoaxial dislocation associated with occipitalized atlas.

In: Wilkins R, Rengachary S (eds):Neurosurgical Operative

atlas, Volume 7. American Association of Neurological

Surgeons, Illinois,1997, pp 249-56

16. SK Shilpakar S, McLaughlin MR, Haid RW, Rodts GE et al.

Management of acute odontoid fractures: operative techniques

and complication avoidance.

Neurosurg Focus 2000; 8: 17-23.

30. Goel A, Laheri V: Plate and screw fixation for atlantoaxial

subluxation.

Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994; 129:47-53.

17. Apfelbaum RI, Lonser RR, Veres R, Casey A. Direct anterior

screw fixation for recent and remote odontoid fractures.

Neurosurg Focus 2000; 8: 7-16.

18. Nakanishi T. Internal fixation of odontoid fractures.

Cent J Orthop Trauma Surg 1980; 23: 399-406.

19. Bohler J. Anterior stabilization for acute fractures and non-

Indian Journal of Neurotrauma (IJNT), Vol. 2, No. 1, 2005

31. Ransford AO, Crockard HA, Pozo JL, et al. Craniocervical

instability treated by contoured loop fixation.

J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1986; 68:173-7.

Acknowledgment

All sketches in this paper have been prepared by Dr.

Bernard T. Lyngdoh

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Quant Job Application ChecklistDocument4 pagesQuant Job Application Checklistmetametax22100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- GEC PE 3 ModuleDocument72 pagesGEC PE 3 ModuleMercy Anne EcatPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing Workshop G7 PDFDocument12 pagesWriting Workshop G7 PDFJobell AguvidaPas encore d'évaluation

- The List InditexDocument126 pagesThe List InditexRezoanul Haque100% (2)

- Final Paper17Document722 pagesFinal Paper17Anjum Shakeela100% (1)

- ZX 470Document13 pagesZX 470Mohammed Shaheeruddin100% (1)

- Strategic CompensationDocument45 pagesStrategic CompensationAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 Post Task Theory Matrix Table RevisedDocument8 pages07 Post Task Theory Matrix Table RevisedHemalyn Bereber100% (1)

- UGC-Social Case Work-Multiple Choice Questions and AnswersDocument11 pagesUGC-Social Case Work-Multiple Choice Questions and AnswersAnjum Shakeela100% (2)

- CHT Wfa Boys P 0 2 Who Growth Chart Boys AdoptionDocument1 pageCHT Wfa Boys P 0 2 Who Growth Chart Boys Adoptiondrjohnckim100% (1)

- Investment PerspectiveDocument4 pagesInvestment PerspectiveAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sampling and MeasurementDocument16 pagesSampling and MeasurementAkshay RajPas encore d'évaluation

- Bone Banking in A Community Hospital: Original StudyDocument6 pagesBone Banking in A Community Hospital: Original StudyAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Imm Material FinalDocument216 pagesImm Material FinalAnjum Shakeela100% (1)

- Pathology Compilation (Solved) - SinghDocument59 pagesPathology Compilation (Solved) - SinghAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- (22)Document19 pages(22)Anjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- 01organisationalchange 130127233413 Phpapp02Document22 pages01organisationalchange 130127233413 Phpapp02SamBensonPas encore d'évaluation

- 670 Challan From PDFDocument1 page670 Challan From PDFSharif JamaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Mistakes: Dr. Muhammad Javaid Asad Associate Professor Department of BiochemistryDocument4 pagesCommon Mistakes: Dr. Muhammad Javaid Asad Associate Professor Department of BiochemistryAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategichrm 131009132007 Phpapp01Document109 pagesStrategichrm 131009132007 Phpapp01Anjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- VisionDocument1 pageVisionAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Format of The PresentationDocument1 pageFormat of The PresentationAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Application Form For Testing: BarcodeDocument5 pagesApplication Form For Testing: BarcodeAasir NaQviPas encore d'évaluation

- QM ch6Document31 pagesQM ch6Shrestha HemPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 1Document75 pagesLecture 1Anjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nlcaf2016 PDFDocument5 pagesNlcaf2016 PDFHamid MasoodPas encore d'évaluation

- KFUEIT Employment Application FormDocument2 pagesKFUEIT Employment Application FormAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Punjab Food Authority: S T NS T NDocument4 pagesPunjab Food Authority: S T NS T NAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- PSSP CWDocument1 pagePSSP CWAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- KFUEIT Employment Application FormDocument2 pagesKFUEIT Employment Application FormAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Political ScienceDocument33 pagesPolitical ScienceAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Political ScienceDocument33 pagesPolitical ScienceAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Helping Employees Cope With ChangeDocument9 pagesHelping Employees Cope With ChangeAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- History of International HRMDocument5 pagesHistory of International HRMAnjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Managemen1Document11 pagesChange Managemen1Anjum ShakeelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Business EthicsDocument42 pagesBusiness EthicsAsesh MandalPas encore d'évaluation

- EarthmattersDocument7 pagesEarthmattersfeafvaevsPas encore d'évaluation

- CV Ilham AP 2022 CniDocument1 pageCV Ilham AP 2022 CniAzuan SyahrilPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Avaliação Edros 2023 - 7º Ano - ProvaDocument32 pages2 Avaliação Edros 2023 - 7º Ano - Provaleandro costaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ciac - HW Brochure Seer 16Document2 pagesCiac - HW Brochure Seer 16Tatiana DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- Retrenchment in Malaysia Employers Right PDFDocument8 pagesRetrenchment in Malaysia Employers Right PDFJeifan-Ira DizonPas encore d'évaluation

- Tugas Gizi Caesar Nurhadiono RDocument2 pagesTugas Gizi Caesar Nurhadiono RCaesar 'nche' NurhadionoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Stony Brook Press - Volume 11, Issue 4Document28 pagesThe Stony Brook Press - Volume 11, Issue 4The Stony Brook PressPas encore d'évaluation

- CA02 ParchamentoJVMDocument6 pagesCA02 ParchamentoJVMJohnrey ParchamentoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cardiovascular Pharmacology: DR Muhamad Ali Sheikh Abdul Kader MD (Usm) MRCP (Uk) Cardiologist, Penang HospitalDocument63 pagesCardiovascular Pharmacology: DR Muhamad Ali Sheikh Abdul Kader MD (Usm) MRCP (Uk) Cardiologist, Penang HospitalCvt RasulPas encore d'évaluation

- Plumber (General) - II R1 07jan2016 PDFDocument18 pagesPlumber (General) - II R1 07jan2016 PDFykchandanPas encore d'évaluation

- Dyestone Blue MX SDS SA-0186-01Document5 pagesDyestone Blue MX SDS SA-0186-01gede aris prayoga mahardikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Good Laboratory Practice GLP Compliance Monitoring ProgrammeDocument17 pagesGood Laboratory Practice GLP Compliance Monitoring ProgrammeamgranadosvPas encore d'évaluation

- Soduim Prescription in The Prevention of Intradialytic HypotensionDocument10 pagesSoduim Prescription in The Prevention of Intradialytic HypotensionTalala tililiPas encore d'évaluation

- Thornburg Letter of RecDocument1 pageThornburg Letter of Recapi-511764033Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nepal Health Research CouncilDocument15 pagesNepal Health Research Councilnabin hamalPas encore d'évaluation

- RA 9344 (Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act)Document10 pagesRA 9344 (Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act)Dan RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Gpat Reference NotesDocument9 pagesGpat Reference NotesPreethi KiranPas encore d'évaluation

- Pioneer Deh-P4850mp p4850mphDocument76 pagesPioneer Deh-P4850mp p4850mphVxr GsiPas encore d'évaluation

- Kerala Medico Legal Code - Annexure2Document19 pagesKerala Medico Legal Code - Annexure2doctor82Pas encore d'évaluation

- DoDough FriedDocument7 pagesDoDough FriedDana Geli100% (1)

- Evolution of Fluidized Bed TechnologyDocument17 pagesEvolution of Fluidized Bed Technologyika yuliyani murtiharjonoPas encore d'évaluation

- Zemoso - PM AssignmentDocument3 pagesZemoso - PM AssignmentTushar Basakhtre (HBK)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Day Case Open Appendectomy: A Safe and Cost-Effective ProcedureDocument9 pagesDay Case Open Appendectomy: A Safe and Cost-Effective ProcedureAcademecian groupPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogo StafsjoDocument12 pagesCatalogo StafsjoBruno Bassotti SilveiraPas encore d'évaluation