Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Article For Journal

Transféré par

awuahbohTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Article For Journal

Transféré par

awuahbohDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

332

Journal of Neuroscience Nursing

Improving Stroke Education Performance

Measures Scores: The Impact of a Stroke

Nurse Coordinator

Josephine Malfitano, Barbara S. Turner, Ed Piper, Penney A. Burlingame,

Elizabeth DAngelo

ABSTRACT

Background: Stroke is a leading cause of death and adult disability worldwide. North Carolina is

considered to be a part of an area of the United States called the stroke belt. Education coupled with

implementation of a program that promotes primary and secondary stroke prevention is paramount to

support the reduction of stroke and improvement of stroke care across the continuum. The groundwork for

stroke care at Onslow Memorial Hospital began in 2006 with participation in the North Carolina Stroke

Care Collaborative (NCSCC), which allowed for benchmarking of data. Methods: A pretest and posttest

design was used to evaluate the effectiveness of a dedicated stroke nurse coordinator on stroke education

performance measure scores. Compliance with stroke education performance measures is met when

documentation reflects education provided or material given during the hospital stay. Three hundred sixty-seven

charts submitted to the NCSCC from Onslow Memorial Hospital were reviewed. Data collected were entered

into the NCSCC Registry database during the period of 2008Y2010. Performance measures were compared at

three points: the year before implementation of the stroke nurse coordinator, the implementation year, and,

the year after the implementation of the stroke nurse coordinator position. Results: Stroke education

performance measure scores for the preimplementation year (2008) were 58.1%, which improved to 86.4%

for the year that the nurse coordinator position was created and filled, and rose to 96.9% for the 1-year

period after the position was filled. Scores from Z tests comparing proportions over time between each of the

3 years were statistically significant. Conclusions: Implementation of a stroke nurse coordinator to improve

stroke care and education is a coordinated effort that will impact stroke outcomes across the healthcare

continuum, with efforts geared toward primary and secondary prevention strategies. This role provides

supportive resources for the community, individualized care with patients and families as well as supporting

staff in providing stroke education, and awareness. Stroke education has shown improvement in patients

understanding the signs and symptoms of stroke as well as improved compliance with treatment plans; the use

of a dedicated educator is supported.

Keywords: education, nurse coordinator, performance measures, quality, stroke, stroke education

troke is a leading cause of death and adult disability worldwide and the fourth leading cause

of death in the United States. North Carolina

Questions or comments about this article may be directed to

Josephine Malfitano, DNP MBA RN FNP CPHQ NE-BC, at jo.malfitano@

onslow.org. She is the Performance Improvement & Accreditation

Manager, Onslow Memorial Hospital, Jacksonville, NC.

Barbara S. Turner, PhD RN FAAN, is the Elisabeth P. Hanes

Distinguished Professor and Director of the Doctor of Nursing Practice

Program at Duke University School of Nursing, Durham NC.

Ed Piper, PhD FACHE, is the President and CEO of Onslow Memorial

Hospital, Jacksonville, NC.

Penney A. Burlingame, DHA RN FACHE, is the Senior Vice President

of Nursing and Clinical Services of Onslow Memorial Hospital,

Jacksonville, NC.

Elizabeth DAngelo, MD, is a Radiologist and Chief of Staff at

Onslow Memorial Hospital, Jacksonville, NC.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Copyright B 2013 American Association of Neuroscience Nurses

DOI: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182a3ce63

ranks fifth in the nation in the incidence of strokes

(American Heart Association, 2011; Huston, 2010;

North Carolina Stroke Care Collaborative [NCSCC],

2010) and is a part of the southeastern United States

called the stroke beltVa cluster of 8Y12 states

with higher stroke mortality than the national average

(NCSCC, 2010). In addition to the human suffering

caused by strokes, the economic impact of strokes in

North Carolina is estimated at 1.05 billion dollars a

year (Holmes, 2008).

Currently, only 18% of adults in North Carolina

can correctly identify stroke signs and symptoms, and

those at high risk for stroke with (hypertension or a

previous stroke) do not know the symptoms any better

than those at lower risk (Holmes, 2008). Educating

the public as well as those who have experienced

stroke, their families, and healthcare professionals on

the signs and symptoms and need for early intervention is one strategy for improving stroke prevention

and outcomes. A focused resource provider who offers

Copyright 2013 American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Volume 45

stroke education to patients, families, and staff is a

means to support one of the stroke quality indicators

proposed by the NCSCC and The Joint Commission.

Background

A lack of prevention strategies and lack of care coordination once stroke patients leave the hospital are

major problems in stroke care (Lennert, 2009). Given

the importance of early intervention for stroke, it is

imperative that patients and families understand risk

factors for stroke, recognize stroke signs and symptoms, and act by calling 9-1-1. Research suggests that

delay in seeking treatment for acute coronary and

stroke symptoms limits effective treatment options

and results in a greater likelihood of permanent disability or death (Huston, 2010). Redfern, Rudd, Wolfe,

and McKevitt (2008) have reported on attempts to improve secondary prevention of stroke through patient

and caregiver education initiatives to improve stroke

knowledge. One approach described was the development of nurse coordinators to transition the patients

care between healthcare providers, with the goal of

improving access to care. Lindsay et al. (2008) found

that stroke education improved patient knowledge of

signs and symptoms of stroke as well as compliance

with the treatment plans for stroke. Similarly, Green

and Newcommon (2006) have reported that implementation of stroke standards of care along with a dedicated stroke educator improved the quality of care for

stroke patients after discharge and also improved systems and processes.

These studies point to the need for focused education interventions to improve stroke care and outcomes.

Yet, despite awareness among health professionals of

the importance of risk factor management for secondary stroke prevention, studies show that adherence

to secondary prevention is still poor (Slark, 2010).

Strategies are needed to involve patients and families

in sharing information, setting goals, and assessing

needs, which are a part of discharge planning (Almborg,

Ulander, Thulin, & Berg, 2009). Understanding the

needs of stroke patients and their families can provide

a basis for educational processes to improve outcomes.

Setting and Methods

In North Carolina, Onslow County is in the southeastern region of the state, a significant risk area for

stroke; it is considered the buckle of the stroke belt,

an area with even greater stroke mortality, three times

higher than the national average (NCSCC, 2010). The

region has high rates of hypertension, cardiovascular

disease, obesity, and diabetesVfactors that put the population at significant risk for stoke according to the

&

Number 6

&

December 2013

Because prevention and early

recognition of stroke are critical in

minimizing the potentially negative

short- and long-term outcomes

related to cerebrovascular disease,

it is imperative that patients and

families receive focused education

that could improve these.

NC County Trends report from the NC Department of

Health and Human Services. Onslow County showed

an increase in stroke deaths in 2006, despite a decline

in overall state deaths from stroke (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services Resources:

Division of Public Health, 2006).

Onslow Memorial Hospital (OMH) is a 162-bed

not-for-profit acute-care community hospital. OMH is

a leader in healthcare to a community that has significant uninsured and underserved populations. These

populations regularly seek acute disease management

through the emergency department because they have

limited access to primary care, and they receive inconsistent follow-up for prevention of recurrent strokes.

OMH began in 2006 through participation in the

NCSCC, benchmarking data. Initial data collected that

year showed that compliance in providing stroke

education was only 28%. There was a clear need to

improve stroke care at OMH. Improvements in stroke

care were made by implementing standing orders,

using evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for

inpatients and the emergency department, improving

dysphagia screening, and the process of expediting

radiology diagnostic testing and developing a stroke

folder with patient education material. Compliance in

stroke education improved to 40% in 2007. However,

the stroke team believed that more could be accomplished with the implementation of a full-time stroke

nurse coordinator (SNC) to provide stroke education/

awareness and prevention strategies to frontline staff,

patients, and families.

OMHs focus is on increasing the states stroke

awareness program using a three-pronged approach:

prevention and education in prehospital screening,

Copyright 2013 American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

333

334

Journal of Neuroscience Nursing

individualized acute care education, and posthospital

follow-up. The dedicated educator/SNC serves as the

liaison and resource for community stroke needs and

patient and family education, while also providing

education and support to hospital staff. The SNC also

facilitates interdisciplinary care coordination and monitors stroke outcomes.

The SNC provides community outreach and education on inpatient and poststroke care by leveraging

NC Stroke Association Programs and by implementing

established standards of stroke care. A Stroke Risk

Identification Screening Program provides standardized protocols for identifying stroke risk factors, counseling participants, directing them to resources, and

providing outcome management through partnerships

for those found to be at high risk for stroke. In this

way, we identify interventions needed or potential

problems with access. A Beyond the Hospital Program

provides evidence-based practice protocols for poststroke education to patients in the acute care setting

and at discharge. Each person is then contacted within

3 months with a follow-up call. This approach provides

TABLE 1.

quantifiable care measures and educational outcomes

for stroke prevention.

The SNC serves as a center for education and facilitation of stroke care across the continuum. The work

begins with programs to increase community awareness and healthcare screenings as well as interactions

with the local health department and emergency management offices to establish collaborations in stroke care.

In the hospital, the stroke nurse makes rounds daily to

reinforce inpatient stroke care based on evidence-based

guidelines. Patients and families are provided educational materials, video-on-demand stroke resources, and

an interdisciplinary plan of care based on individual

needs. The SNC ensures that staff education is ongoing

from the time of orientation to the organization; the education includes annual mandatory computerized module

learning, regular staff meetings, and real-time feedback

with chart reviews and updated care management discussions. The SNC is readily accessible to staff via

pager and also supports families. The coordinator also

reviews cases, analyzes and shares data for stroke improvement initiatives, and serves as a resource for other

Demographics by Years 2008Y2010

N (%) by Year

Variables

Overall, n (%)

Year 2008

Year 2009

Year 2010

(N = 418)

n = 126 (%)

n = 143 (%)

n = 149 (%)

18 (4.3)

7 (5.6)

5 (3.5)

6 (4.0)

Age in groups, years

18Y44

45Y64

150 (35.9)

50 (39.7)

45 (31.5)

55 (36.9)

65Y74

102 (24.4)

33 (26.2)

42 (29.4)

27 (18.1)

75+

148 (35.4)

36 (28.6)

51 (35.7)

61 (40.9)

Male

187 (44.7)

61 (48.4)

51 (35.7)

75 (50.3)

Female

231 (55.3)

65 (51.6)

92 (64.3)

74 (49.7)

White

300 (71.8)

88 (69.8)

99 (69.2)

113 (75.8)

Black

108 (25.8)

32 (25.4)

42 (29.4)

34 (22.8)

Others

10 (2.4)

6 (4.8)

2 (1.4)

2 (1.3)

12 (2.9)

2 (1.6)

4 (2.8)

6 (4.0)

Non-Hispanic White

288 (68.9)

86 (68.3)

95 (66.4)

107 (71.8)

Non-Hispanic Black

108 (25.8)

32 (25.4)

42 (29.4)

34 (22.8)

10 (2.4)

6 (4.8)

2 (1.4)

2 (1.3)

283 (67.7)

78 (61.9)

106 (74.1)

99 (66.4)

Private

40 (9.6)

5 (4.0)

6 (4.2)

29 (19.5)

No insurance

29 (6.9)

5 (4.0)

4 (2.8)

20 (13.4)

Not documented

66 (15.8)

38 (30.2)

27 (18.9)

1 (0.7)

Gender

Race

Race and ethnicity

Hispanic White

Others

Health insurance

Medicare/Medicaid

Copyright 2013 American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Volume 45

&

Number 6

&

December 2013

TABLE 2. Stroke Education Compliance Scores Z Test Comparison Proportions Over Time

Sample Population:

Stroke Only

Sample Population:

Stroke and TIA

Comparing Proportions

Over Time:

Probability by Year

Sample Population:

Stroke Only

Year

Performance

Measure Score

Performance

Measure Score

Year

Z Score

2008

62

58.1

108

49.1

2008Y2009

3.716

.0001

2009

66

86.4

120

80.0

2009Y2010

2.2003

.0139

2010

65

96.9

104

91.3

2008Y2010

5.8097

G.0001

2011a

21

95.2

35

97.1

Note. Data provided by NCSCC.

a

Statistically significant at p G .05.

facilities to network, benchmark data, and develop best

practices measures in stroke care.

Key supporters of the role of the SNC are stroke

champions, including those in frontline nursing, rehabilitation, radiology, pharmacy, dietary, education, local

Emergency Medical Services, emergency department

staff/providers, and leadership. The SNC facilitates

the work of interdisciplinary teams so that stroke care

and education are consistent across the continuum.

Evidence-based practice guideline protocols and policies

as well as tools and checklists for more effective and

efficient documentation have been developed. Hardwiring system improvements and processes include

checklist documentation on the nursing record and

interdisciplinary discharge plans of care. Local newspaper

articles have been developed on stroke awareness, along

with Web sites and videos. Additional educational resources include a stroke awareness packet, stroke risk

pamphlet, and stroke publication flyers provided to

patients and staff.

Stroke education is one of 10 quality performance

indicators endorsed by the National Quality Forum. The

stroke education performance measures state that meeting compliance in stroke education requires that documentation of ischemic stroke patients or their caregivers

were given educational material during their hospital stay

addressing all of the following five elements: activation

of the emergency medical system, follow-up after discharge, medications prescribed at discharge, risk factors for stroke, and warning signs and symptoms of

stroke (The Joint Commission and Center of Medicare/

Medicaid Services, 2011).

Accurate and consistent documentation of education

must be recorded in the medical record. When documentation is incomplete, the performance is considered

a failure or variance.

To determine whether an SNC improved stroke

education, we collected data at three measurement

points to see if there were significant trends in stroke

education performance scores: 2008, the year before

introduction of the SNC; 2009, the year of implementation; and 2010, the year after implementation of

the SNC position. The first 6 months of 2011 were

also analyzed to determine if improvements were sustained. During 2008Y2011, 418 stroke patient charts

were reviewed. To be included in the analysis, patients

had to be 18 years old or older and discharged with an

ICD-9 for stroke. Patients who had a length of stay

greater than 120 days, palliative care patients, and patients

enrolled in clinical trials or patients admitted for elective

FIGURE 1 Stroke Education Performance Measure Scores by Year: Stroke Patients Only

Copyright 2013 American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

335

336

Journal of Neuroscience Nursing

FIGURE 2 Stroke Education Performance Measure Scores by Year: Ischemic Stroke and

TIA Patients

carotid intervention were excluded. Using these inclusion criteria, there were 367 charts eligible for review.

The NCSCC conducts a data quality assessment

annually. Reliability of 5% of the data entered into the

NCSCC Registry from April 2009 through June 2010

was examined to determine if the data submitted to

the NCSCC were in agreement with the medical record documentation. There was 95% congruence in

data elements. Additional quality assessment was conducted through case ascertainment to determine if the

number of stroke cases admitted to the hospital during

a designated 60-day period was consistent with the

number of missing cases entered and to determine if

the number and type of stroke cases admitted to the

hospital during a 1-year period was comparable with

those entered into the NCSCC.

Data abstraction followed consistent and recognized national guidelines. Data for obtaining stroke

education performance measures were collected using

retrospective chart audits following the format of the

NCSCC stroke care cards, which contain numerous

questions to determine if documentation to support

compliance with performance indicators is maintained.

Charts were selected for review using patients who

were discharged with an ICD-9 stroke code. The sample included 100% of the stroke patients who were

hospitalized in the preimplementation and postimplementation times. Charts were reviewed monthly,

and data abstraction was done by the SNC and three

performance improvement personnel, who were trained

to abstract data and follow the prescribed definitions

to enter the data into the appropriate databases. Assigning consistent staff for data abstractions prevented variability in the interpretation of the data. To further support

the reliability and integrity of the data, queries related

to stroke performance measures that were identified during chart abstraction were filtered through the NCSCC

Registry or the Joint Commission for clarification.

Data Analysis

Three hundred sixty-seven patient records from 2008

to 2011, including 35 chart audits during JanuaryY

June 2011, were analyzed. All included inpatients with

a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke and/or transient

ischemic attack who met the inclusion criteria.

Table 1 depicts the demographic of the sample, and

Table 2 and Figures 1Y3 document improvement in stroke

education compliance scores, from 58.1% in the year

before the initiation of the SNC role to 86.4% in the

year the role was filled and 96.9% in the year after the

role was initiated. Data for 2011 (partial year) showed

continued sustainability of the improvement, at 95.2%.

FIGURE 3 Stroke Education Performance Measures Scores by Year: Ischemic Stroke

and/or TIA Patients Comparing Onslow Memorial Hospital and North

Carolina Stroke Care Collaborative

Copyright 2013 American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Volume 45

When the data from patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack were analyzed, the improvements

in stroke education compliance scores were similar to

those for stroke alone.

Discussion

Implementation of the SNC role was associated with

improved stroke education performance measure scores.

The coordinator provides supportive resources for the

community and individualized care for patients and

families, while also supporting staff in providing stroke

education and awareness. The SNC functions to align

collaborative stroke care efforts for seamless process

improvement in the acute care setting. Studies of compliance in poststroke care management at home have

shown that adherence to secondary prevention is still

poor, supporting the significance of this role for stroke

education and awareness among healthcare professionals, patients, and families (Slark, 2010). Stroke

healthcare teams need to develop strategies to involve

relatives of stroke patients in sharing information,

goal setting, and discharge planning (Almborg et al.,

2009). Understanding the needs of stroke patients

and their families can assist the care team to provide

education for improved outcomes. Additional considerations include further investigations that will

align the compliance with performance measures and

outcomes notable with strategies currently being

implemented such as with postdischarge telephone

calls and demonstration of readmission reduction.

Since the implementation of the SNC role at OMH,

stroke education compliance has shown sustained

improvements, from 58% in 2008, the year before

implementation of the coordinator, to 86% in 2009

(the implementation year) and 96% at the end of

2010 (1-year post implementation of the SNC role).

In the first 6 months of 2011, the data continue to show

sustainability, with stroke education performance

scores at 95%.

Of interest is that the data from OMH, when compared with North Carolina statewide scores, show higher

performance measures for 2009Y2011Vthe time period associated with the use of the dedicated SNC.

The best way to treat a stroke is to prevent it (Albert,

2011). Education is the mechanism for delivering this

messageVprimary prevention and, in the case of the

population involved in the study, secondary prevention. Patients who have had a stroke are at higher risk

for another stroke. Education coupled with implementation of a program that promotes primary and/or

secondary stroke prevention is paramount to support

the reduction of stroke and improvement of stroke care

across the continuum. Strategies that enhance patient

and professional awareness of stroke risk factors are

&

Number 6

&

December 2013

feasible to produce and deliver and can improve stroke

care and disease management (Lennert, 2009). The

SNC role supports stroke care improvement interventions and strategies for increasing education and awareness of risk factors, medications, signs, and symptoms

of stroke and activation of emergency management

system calling 9-1-1.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in part through the North

Carolina Stroke Care Collaborative, North Carolina

Stroke Association, and Kate B. Charitable Trust.

Data were provided through the North Carolina

Stroke Care Collaborative.

References

Albert, M. (2011). Personal communication. Northwestern University. m-alberts@northwestern.edu

Almborg, A., Ulander, K., Thulin, A., & Berg, S. (2009).

Review: Understanding the needs of families: Discharge

planning of stroke patients: The relatives perceptions of

participation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18, 857Y865.

American Heart Association. (2011). About stroke. Retrieved

http://www.strokeassociation.org/STROKEORG/AboutStroke/

AboutStroke_UCM_30829_SubHomePage.jsp

Green, T., & Newcommon, N. (2006). Advanced nursing practice:

The role of the nurse practitioner in an acute stroke program.

Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 38(4), 328Y330.

Holmes, A. (2008). Stroke in North Carolina: Addressing the burden

together. Raleigh, NC: NC Stroke Advisory Council Meeting.

Huston, S. (2010). Heart disease and stroke prevention branch

chronic disease and injury section: The burden of cardiovascular disease in North Carolina (annual report). Division

of Public Health, North Carolina Department of Health &

Human Service. Retrieved from http://www.startwithyourheart

.com/Default.aspx?pn=CVDBurden

Lennert, B. (2009). Care management for TIA and stroke

patients: Riding the quality improvement wave. American

Health and Drug Benefits, 2(6, Suppl. 8), S24YS27.

Lindsay, P., Bayley, M., Hellings, C., Hill, M., Woodbury, E.,

& Phillips, S. (2008). Public awareness and patient

education: Patient and family education. Canadian Medical

Association Journal, 179(Suppl. 12), 15Y16.

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services Resources: Division of Public Health. (2006). North Carolina

Statewide and County Trends in key health indicators: Onslow

County. Raliegh, NC: State Center of Health Statistics.

North Carolina Stroke Care Collaborative. (2010). North

Carolina in the buckle of the stroke belt. Retrieved http://

ncstrokeregistry.com/stroke2010/Overview/Stkbuckle.htm

Redfern, J., Rudd, A., Wolfe, C., & McKevitt, C. (2008). Stop

stroke: Development of an innovative intervention to

improve risk factor management after stroke. Patient

Education and Counseling, 72, 201Y209.

Slark, J. (2010). Adherence to secondary prevention strategies

after stroke: A Review of the literature. British Journal of

Neuroscience Nursing, 6(6), 282Y286.

The Joint Commission and Center of Medicare/Medicaid

Services. (2011). Specifications Manual for National

Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures (Version 3.2c) [data

file]. Washington, DC: Author.

Copyright 2013 American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

337

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- NCLEX Random FactsDocument34 pagesNCLEX Random FactsLegnaMary100% (8)

- Oop Say You Know MeDocument1 pageOop Say You Know MeawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- The BSN Job Search: Interview Preparation: Telling Your StoryDocument25 pagesThe BSN Job Search: Interview Preparation: Telling Your StoryawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- King Rush MoreDocument1 pageKing Rush MoreawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Article For JournalDocument6 pagesArticle For JournalawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Middle Age Adult Health History Assignment Guidelines N315 Fall 2013Document23 pagesMiddle Age Adult Health History Assignment Guidelines N315 Fall 2013awuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- HandOff SampleToolsDocument9 pagesHandOff SampleToolsOllie EvansPas encore d'évaluation

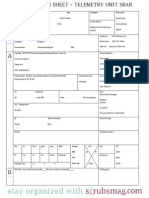

- Nurse Brain Sheet Telemetry Unit SBARDocument1 pageNurse Brain Sheet Telemetry Unit SBARvsosa624Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pharm NclexDocument9 pagesPharm NclexawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Drugs NclexDocument30 pagesDrugs Nclexawuahboh100% (1)

- Probability of A or B and A and B-1Document2 pagesProbability of A or B and A and B-1awuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Article For CET CHFDocument5 pagesArticle For CET CHFawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- PolypharmacyDocument24 pagesPolypharmacySurina Zaman HuriPas encore d'évaluation

- Massachusetts Department of Public HealthDocument24 pagesMassachusetts Department of Public HealthawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Random FactsDocument338 pagesRandom Factscyram81100% (1)

- EBP Article 1Document11 pagesEBP Article 1awuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- EBP Article 3Document6 pagesEBP Article 3awuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Article For CET CHFDocument5 pagesArticle For CET CHFawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Tips On Answering NclexDocument4 pagesTips On Answering NclexawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- ENT Throat and EsophagusDocument41 pagesENT Throat and EsophagusMUHAMMAD HASAN NAGRAPas encore d'évaluation

- Therapeutic CommunicationDocument1 pageTherapeutic CommunicationawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Thinking StrategiesDocument3 pagesCritical Thinking StrategiesawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Does Prospective Payment Increase Hospital (In) Efficiency? Evidence From The Swiss Hospital SectorDocument24 pagesDoes Prospective Payment Increase Hospital (In) Efficiency? Evidence From The Swiss Hospital SectorawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- STDA VaricealDocument8 pagesSTDA VaricealDeisy de JesusPas encore d'évaluation

- Debate 3 Youth Incarceration in Adult PrisonsDocument6 pagesDebate 3 Youth Incarceration in Adult PrisonsawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Patient Report FormDocument1 pagePatient Report FormawuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Parkland formula and rule of 9Document8 pagesParkland formula and rule of 9awuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Article For Journal 4-18-14Document8 pagesArticle For Journal 4-18-14awuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- Article For Jouranal 2 (498P)Document5 pagesArticle For Jouranal 2 (498P)awuahbohPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Enabling Keycloak Metrics - KeycloakDocument3 pagesEnabling Keycloak Metrics - Keycloakhisyam darwisPas encore d'évaluation

- MN00119 Unicom LT User ManualDocument45 pagesMN00119 Unicom LT User ManualPhilipp A IslaPas encore d'évaluation

- 3.0 Wrap Up and SummaryDocument4 pages3.0 Wrap Up and SummaryGian SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Finimpianti Power EngDocument2 pagesFinimpianti Power EngJosip GrlicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing Emails Part 1 Informal British English Teacher Ver2Document7 pagesWriting Emails Part 1 Informal British English Teacher Ver2Madalina MandiucPas encore d'évaluation

- MDS Report Substances of Assemblies and Materials: 1. Company and Product NameDocument17 pagesMDS Report Substances of Assemblies and Materials: 1. Company and Product Namejavier ortizPas encore d'évaluation

- Cartoon Network, Boomerang & TCM TV Rate Card July - SeptemberDocument11 pagesCartoon Network, Boomerang & TCM TV Rate Card July - SeptemberR RizalPas encore d'évaluation

- Food Conformity BA 550-13Document9 pagesFood Conformity BA 550-13puipuiesperaPas encore d'évaluation

- Toolbox Meeting Or, TBT (Toolbox TalkDocument10 pagesToolbox Meeting Or, TBT (Toolbox TalkHarold PoncePas encore d'évaluation

- Formulating and Solving LPs Using Excel SolverDocument8 pagesFormulating and Solving LPs Using Excel SolverAaron MartinPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental AspectDocument29 pagesMental AspectBenjii CarlosPas encore d'évaluation

- Innovations in Drill Stem Safety Valve TechnologyDocument22 pagesInnovations in Drill Stem Safety Valve Technologymiguel mendoza0% (1)

- Attitudes and Practices Related To Sexuality and Sexual BehaviorDocument35 pagesAttitudes and Practices Related To Sexuality and Sexual BehaviorGalvin LalusinPas encore d'évaluation

- Texas Final LeadsDocument36 pagesTexas Final Leadsabdullahmohammed4460Pas encore d'évaluation

- Query Operation 2021Document35 pagesQuery Operation 2021Abdo AbaborPas encore d'évaluation

- IIT BOMBAY RESUME by SathyamoorthyDocument1 pageIIT BOMBAY RESUME by SathyamoorthySathyamoorthy VenkateshPas encore d'évaluation

- Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Fibrin On Socket Healing After Mandibular Third Molar ExtractionsDocument10 pagesEfficacy of Platelet-Rich Fibrin On Socket Healing After Mandibular Third Molar Extractionsxiaoxin zhangPas encore d'évaluation

- Statistics Interview QuestionsDocument5 pagesStatistics Interview QuestionsARCHANA R100% (1)

- 1729Document52 pages1729praj24083302Pas encore d'évaluation

- DodupukegakobemavasevuDocument3 pagesDodupukegakobemavasevuMartian SamaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Proposal BP3IP FinalDocument3 pagesProposal BP3IP FinalGiant SeptiantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Frame Fit Specs SramDocument22 pagesFrame Fit Specs SramJanekPas encore d'évaluation

- American With Disabilities Act AdaDocument16 pagesAmerican With Disabilities Act Adaapi-376186426Pas encore d'évaluation

- CP QB PT-3 Harish KumarDocument3 pagesCP QB PT-3 Harish KumarVISHNU7 77Pas encore d'évaluation

- Zeal Institute of Manangement and Computer ApplicationDocument4 pagesZeal Institute of Manangement and Computer ApplicationSONAL UTTARKARPas encore d'évaluation

- CM Group Marketing To Gen Z ReportDocument20 pagesCM Group Marketing To Gen Z Reportroni21Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of PDocument9 pagesA Study To Assess The Effectiveness of PKamal JindalPas encore d'évaluation

- Grupo Stoncor Description - Stonhard Carboline Fibergrate PDFDocument22 pagesGrupo Stoncor Description - Stonhard Carboline Fibergrate PDFAndres OsorioPas encore d'évaluation

- Formal Analysis of Timeliness in Electronic Commerce ProtocolsDocument5 pagesFormal Analysis of Timeliness in Electronic Commerce Protocolsjuan david arteagaPas encore d'évaluation

- 3ADW000379R0301 DCS550 Manual e CDocument310 pages3ADW000379R0301 DCS550 Manual e CLaura SelvaPas encore d'évaluation