Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Uruguay'S Evolving Experience of Amnesty and Civil Society'S Response

Transféré par

frankiepalmeriDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Uruguay'S Evolving Experience of Amnesty and Civil Society'S Response

Transféré par

frankiepalmeriDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

URUGUAYS EVOLVING EXPERIENCE OF

AMNESTY AND CIVIL SOCIETYS

RESPONSE

BY LOUISE MALLINDER *

WORKING PAPER NO. 4 FROM BEYOND LEGALISM: AMNESTIES, TRANSITION AND

CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION

INSTITUTE OF CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

QUEENS UNIVERSITY BELFAST

MARCH 2009

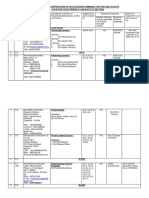

1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 1

2. URUGUAYS EXPERIENCE OF MILITARY RULE, 1976-1984 ............................................................................. 4

3. DEMANDS FOR AMNESTY AND POLITICAL CHANGE, 1980-1984 ................................................................. 13

4. TOP-DOWN TRANSITION: 1984 PACTO DEL CLUB NAVAL AND LIMITED PRISON RELEASES ....................... 18

5. ELECTIONS AND LIMITED TRUTH RECOVERY ............................................................................................... 25

6. 1985 LEY DE PACIFICACIN NACIONAL ....................................................................................................... 28

A) PRISON RELEASES ............................................................................................................................................... 32

B) RESTITUTION AND REPATRIATION .......................................................................................................................... 34

C) EVALUATING THE LAW OF NATIONAL PACIFICATION .................................................................................................. 36

7. GROWING PRESSURE TO HOLD THE MILITARY ACCOUNTABLE ................................................................... 38

A) BATTLING FOR JURISDICTION OVER HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES ....................................................................................... 38

B) BOTTOM-UP TRUTH-RECOVERY: SERPAJS NUNCA MS PROJECT............................................................................ 40

8. SLIDING TOWARDS ENACTING MILITARY IMPUNITY .................................................................................. 41

A) THE FIRST COLORADO PARTY BILL, JULY 1986 ......................................................................................................... 44

B) THE BLANCO BILL ............................................................................................................................................... 45

C) BREAKING THE IMPASSE ....................................................................................................................................... 47

The author will like to thank all of our interviewees within Uruguay.

Funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council, this two-year comparative research project is

exploring the relationship between amnesties and transition from conflict. Through a combination of research

methods, including fieldwork, the project is examining amnesty processes in South Africa, Uganda, Argentina,

Uruguay and Bosnia-Herzegovina. It is looking in particular at the following themes: (1) amnesty, political

power and the construction of legitimacy; (2) amnesty, truth recovery and public memory; (3) amnesty and

accountability; (4) amnesty and the construction of victim and perpetrator; (5) amnesty, forgiveness and

reconciliation; and (6) amnesty and the limitations of legalism.

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

9. LEY DE CADUCIDAD DE LA PRETENSIN PNITIVA DEL ESTADO, LEY NO 15,848 (1986) .............................. 50

10. FIRST ANTI-IMPUNIDAD REFERENDUM CAMPAIGN, 1987-1989 ............................................................... 53

11. IMPACT OF THE REFERENDUM AND THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE LEY DE CADUCIDAD ........................ 55

12. INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGN AGAINST THE LEY DE CADUCIDAD: COMPLAINTS TO THE INTER-AMERICAN

COMMISSION AND THE UN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE ............................................................................. 59

13. IMPLEMENTING ARTICLE 4 OF THE LEY DE CADUCIDAD: COURT ORDERED INVESTIGATIONS AND THE

COMISIN PARA LA PAZ ................................................................................................................................. 60

14. REINTERPRETING THE AMNESTY AND CURRENT CRIMINAL INVESTIGATIONS .......................................... 65

15. SECOND REFERENDUM ANTI-IMPUNIDAD CAMPAIGN ............................................................................. 68

16. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................ 70

KEY SOURCES ................................................................................................................................................. 72

A) BOOKS ............................................................................................................................................................. 72

B) JOURNAL ARTICLES AND BOOK CHAPTERS ............................................................................................................... 73

C) REPORTS AND CONFERENCE PAPERS....................................................................................................................... 75

D) STATUTES, REGULATIONS AND AGREEMENTS ........................................................................................................... 75

E) CASE LAW ......................................................................................................................................................... 75

F) USEFUL WEBSITES .............................................................................................................................................. 76

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

1. INTRODUCTION

During the Uruguayan transition from repressive military rule to democracy during the

1980s, two contrasting amnesty laws were introduced. The first, enacted in 1985 soon after

the inauguration of the civilian president, benefited those who had suffered directly from

military abuses in numerous ways including being dismissed from government posts, being

forced into exile, being detained and tortured, and in many cases being imprisoned for

lengthy periods. Although some of the individuals who were released from prison in

accordance with this amnesty were left-wing guerrillas, the majority had been punished for

their perceived political views, rather than as a result of any criminal behaviour.

Consequently, in many cases, rather than being a tool for impunity, the 1985 amnesty law

can be viewed as a form of reparations which sought to undo some of the harm that had

been inflicted during military rule. Furthermore, many of the individuals who benefited had

been convicted for their (alleged) actions, and in such cases, the 1985 amnesty did not shield

individuals from criminal liability, but rather lessened the punishments. In contrast, the

second amnesty law, enacted in 1986 in response to military demands, granted automatic,

blanket immunity from prosecution to those who were deemed to have committed political

crimes in the course of carrying out official functions, including members of the armed and

security forces who had been explicitly excluded from the 1985 amnesty.

The heated debates surrounding the enactment of these laws were reflective of the balance

of power between the parties to the transition, and the amnesties became a nexis for the

contested narratives over the actions of the military and the left-wing guerrillas before and

during the dictatorship, the threat posed by the military to democracy following the

transition, and understandings of the nature of democracy. In this context, as with

experiences elsewhere in South America, during and after the handover of power, sectors of

armed forces, with the support of some democratic politicians, demanded an amnesty. They

argued an amnesty would be a recognition that, notwithstanding some excesses, the

militarys actions in the war against subversion had not been criminal, but rather had been

to protect the state from the threat of communism. This understanding of amnesty as an

acknowledgement of the selfless actions of the armed forces counters not only the reality

of the crimes perpetrated by the military juntas, but also the assumption underpinning

amnesty laws that crimes have been committed and that, without the amnesty, the

offenders would be liable for prosecution. As will be explored in this report, these contested

narratives provide a prism through which to explore the construction of collective memory

and legitimacy within transitional states.

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

The background to the amnesty processes in Uruguay shares many characteristics with

political transitions in Latin America and elsewhere, notably the experience of brutal military

dictatorship. However, it retains some unique characteristics. Firstly, Uruguay, unlike its

neighbour Argentina, did not have a long history of political conflict and military

assertiveness. Consequently, amnesty laws had not been a frequently implemented political

tool prior to the transition.

Secondly, the main forms of human rights violations during military rule were torture and

prolonged imprisonment, rather than disappearances or massacres. As most of the human

rights violations perpetrated did not result in the death of the victim, the military regime in

Uruguay could be argued to have been less brutal than its neighbours. However, as will be

argued in this report, the comparative smallness of Uruguay (both territorially and

demographically), coupled with the extent of state control over both the public and private

spheres meant that military repression can be argued to have directly affected the lives of all

Uruguayans.

Thirdly, the Uruguayan military initiated the transition and negotiated their withdrawal from

power with political elites in a secretive, top-down process, which enabled them to maintain

significant influence over the transition, and to maintain a political role following the

democratic elections. Furthermore, unlike more recent transitional negotiations elsewhere,

the Uruguayan talks were conducted with little international input on the human rights

violations, although the violence of the military was part of a hemisphere-wide campaign of

repression of left-wing activists.

Fourthly, as the transition began rather rapidly, civil society had not been campaigning

against military rule and human rights abuses for as long as in Argentina, and consequently,

was less organised and united during the negotiations. This was mirrored by a lack of

consensus on justice issues among the political parties. However, following the enactment of

the 1986 amnesty, civil society mobilised and launched a mass campaign to overturn the

amnesty, which culminated in a referendum in 1989, in which the population voted in favour

of the amnesty. The experience of this referendum, in which civil society used legal

approaches to ignite a national conversation on crimes of the dictatorship and to try to

overturn the amnesty law, is highly significant for the Beyond Legalism study as it speaks to

issues of legitimacy in the use of amnesty laws. Furthermore, at the time of writing, the issue

has been reopened as civil society has launched a second campaign to force a referendum

on the amnesty. As yet, it is unclear whether sufficient signatures will be gathered in time to

trigger the referendum to coincide with the next presidential election due in October 2009,

but this ongoing process, which corresponds to current efforts to address historical

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

amnesties in countries such as Spain, provides a context in which to explore how the

legitimacy of amnesty develops over time and how far developments in the international

campaign against impunity can impact on attitudes towards the amnesty within Uruguay.

Finally, the 1986 amnesty law is significant as it gave the judiciary the power to implement

the amnesty, but it awarded the executive control over investigations into disappearances.

Whilst in theory this meant that the amnesty could co-exist with truth-recovery initiatives

and trials, in practice for much of the time since the laws enactment, the executive has

relied on the amnesty to curb judicial investigations into the crimes of the past.

This report was initially drafted as part of a series of background papers that were written in

preparation for fieldwork in each of the five jurisdictions being investigated in the Beyond

Legalism project. As with the other background papers, this report aims to explore:

The political context that gave rise to the amnesty laws and the reaction of civil society

to these laws

The scope of the amnesties that were enacted

The process of implementing the amnesty and whether the amnestys scope changed

over time as a result of judicial decisions and executive policies

The relationship between the amnesty and other transitional justice mechanisms, both

national and international

In addition, each of the background papers attempts to consider the impact of amnesties

within the states concerned. Following the Beyond Legalism teams fieldwork in Uruguay in

November 2008, this paper was redrafted drawing on our increased understandings of the

Uruguayan context. This working paper does not, however, draw directly on the views

expressed by our interviewees. Instead, their views will be discussed in depth in our final

project publications, which will be released during 2009 and 2010.

In charting the history of amnesties in Uruguay, this paper will begin in Part 2 by providing a

brief overview of the circumstances that gave rise to military rule and the consequences of

the dictatorship on society. Then in Part 3 it will explore the moves towards a negotiated

transition and the growing civil society demands for amnesty for political prisoners. Part 4

will analyse the terms of the Naval Club Pact and the role that amnesty played in the

negotiations. This pact led to democratic elections and the creation of parliamentary

investigative commissions which will be discussed in Part 5. Part 6 will subsequently explore

the scope and impact of the National Pacification Law, which benefited political prisoners

and exiles. The elite driven Naval Club Pact and National Pacification process were followed

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

by bottom-up pressure for truth and justice, which will be considered in Part 7. This

pressure contributed to the issue of amnesty for military and police officers resurfacing in

1986 as outlined in Part 8 and the resulting Ley de Caducidad will be explored in Part 9. The

referendum challenge of civil society to the amnesty will be discussed in Part 10 and the

impact of the referendum and the Ley de Caducidad will analysed in Part 11. Although the

amnesty provided broad impunity for state officials, attempts to provide truth, justice and

reparations continued at the international level, as explored in Part 12, and then increasingly

at the domestic level from the late 1990s, which will be discussed in Part 13. Part 14 will look

at the current efforts to reinterpret the amnesty law and Part 15 will discuss the current

campaign to trigger a second referendum to annul the amnesty.

This paper will argue that Uruguay provides an important case study that highlights how civil

society can engage with the amnesty issue, and how the wider population respond.

Furthermore, the experience of the amnesty laws in Uruguay illustrates how the scope of

amnesty laws can change over time through new interpretations in response to changing

political contexts and legal developments.

2. URUGUAYS EXPERIENCE OF MILITARY RULE, 1976-1984

Before the military coup in 1973, Uruguay was often referred to internally and externally as

Uruguay Feliz or the Switzerland of the Americas.1 These favourable descriptions were

based on a number of factors. Firstly, Uruguay, along with Chile, had the longest tradition of

democracy on the continent, which predated the democratic traditions of many European

countries.2 Secondly, Uruguay at this time benefited from a social and political consensus,3

which permitted it to develop progressive social welfare policies and advanced educational

and health systems.4 Due to these favourable conditions, Uruguay, unlike Argentina, did not

have a tradition of frequently using amnesty laws as political tools in its recent history.5 This

1

Eg Philip Taylor, Government and Politics of Uruguay (Tulane University Press, New Orleans 1960) or La Suiza

de Amrica y Sus Mitos in Gerardo Caetano & Milita Alfaro (eds) Historia del Uruguay Contemporneo:

Materiales para el Debate (1995).

2

Alexandra Barahona de Brito, Truth and Justice in the Consolidation of Democracy in Chile and Uruguay

(1993) 46 Parliamentary Affairs 579, 581.

3

Ronaldo Munck, Latin America: The Transition to Democracy (Zed Books, London 1989) 174.

4

Zelmar Lissardy, Uruguay Releases Leftist Guerrillas under Amnesty United Press International (Montevideo

13 March 1985).

5

However, according to Roniger and Sznajder, amnesties had been used in the decades following Uruguayan

independence: In Uruguay, amnesties and pardons were granted in 1835 at the end of the wars of

independence and again in 1854 and 1860; in 1872 an amnesty put an end to a rebellion of Timteo Aparicio; in

1875 those involved in the Revolution of the Tricolor were pardoned; in 1897 pardons were granted to those

involved in the rebellion of Aparicio Saravia, followed by a formal agreement between the victors and the

defeated in 1904; pardons followed the uprising of Cerillos in 1926; in 1935 the Terra Dictatorship was closed

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

makes the Ley de Caducidad, which offered a broad amnesty for crimes committed during

the military dictatorship exceptional in the Uruguayan context, and it can be speculated

whether this affected the laws perceived legitimacy.

The political and social conditions in Uruguay began to deteriorate from the 1960s when a

slump in the countrys basic exports led to labour strikes and the formation of left-wing

guerrilla groups,6 notably the left-wing Movimiento de Liberacin Nacional, or Tupamaros.7

The Tupamaros, began secretly organising in 1962 and launched their military offensive in

1966 following national elections. Their primary objective was to build a popular political

consciousness around the assertion that Uruguays traditional power structures were

corrupted beyond repair, and that nothing short of their total destruction would bring

satisfactory change.8 Their operations were focused in Montevideo and their tactics

included [r]aiding banks, casinos, factories, and other symbols of upper-class power and

United States imperialism.9 In seeking to influence public opinion, the Tupamaros often

used satire in their propaganda and redistributed, Robin Hood-style, the goods they

seized.10 They also sought to minimise civilian casualties and accomplish their direct

missions from a moral high ground.11 Furthermore, in a Carta Abierta de los Tupamaros a la

Polica (Open Letter to the Police) published in the leftist magazine, Epoca, on 7 December

1967, the Tupamaros sought to justify their armed struggle by stating [w]e have placed

ourselves outside the law because

This is the only honest action when the law is not equal for all; when the law exists to

defend the spurious interests of a minority to the detriment of the majority; when

by a law of pardon. See Luis Roniger and Mario Sznajder, The Legacy of Human Rights Violations in the

Southern Cone: Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay (Oxford Studies in Democratization, Oxford University Press,

Oxford 1999) 140.

6

Ibid. During the early 1970s there were other smaller left-wing guerrilla groups active in Uruguay including the

Organizacin Popular Revolucionaria 33 (OPR-33) and the Movimiento Revolucionario Oriental (MRO).

7

The name Tupamaros is derived from an ill-fated 1780 insurrection against the Spanish conquistadors led by

an Inca chieftain named Tupac Amaru.

8

Christopher A. Woodruff, Political Culture and Revolution: An Analysis of the Tupamaros Failed Attempt to

Ignite a Social Revolution in Uruguay (Lonzano Long Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Texas at

Austin, 4 January 2008) 2.

9

Ibid 2.

10

Zelmar Lissardy, Uruguay Releases Leftist Guerrillas under Amnesty United Press International (Montevideo

13 March 1985).

11

Woodruff (n 8) 15. Woodruff cites a study by Eduardo Rey Tristn which argues that in seven years of

operations, the Tupamaros were only responsible for 40 deaths.

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

the law works against the countrys progress; when even those who have created it

place themselves outside it, with impunity, whenever it is convenient to them.12

In this way, the Tupamaros sought to distinguish their actions from purely criminal

behaviour and tried to carve a niche within societys conception of legitimacy.13 Although

such radicalism was antithetical to Uruguayan societys traditional convictions, the

Tupamaros gained considerable public support in the late 1960s,14 and for a while were

regarded as Latin Americas best organised urban guerrilla force.15 This success was shortlived, however, as by 1973 the military had crushed them.16

Although the military did not assume complete control of government until after their

defeat of the Tupamaros, the 1966 elections that had preceded the guerrillas armed

campaign brought to power a repressive, right-wing Colorado government, under the

presidency of Jorge Pacheco Areco. President Pacheco rapidly began to suppress dissent by

banning left-wing political parties and closing down newspapers, and in 1968 he used the

guerrilla threat to impose a state of emergency, a measure which was unopposed by

Congress.17 From this period, the police began to use force to suppress demonstrations and

torture became routine during interrogations.18 Furthermore, from 1969 President Pacheco

ordered the military to intervene to stop strikes19 and following the escape of 100

Tupamaros from Punta Carretas prison in 1971, Pacheco handed the military full control of

counter-insurgency operations.20 In the subsequent general elections in November 1971,

12

Lawrence Weschler, A Miracle, A Universe: Settling Accounts with Torturers (University of Chicago Press,

Chicago, Ill. 1998) 103. Unsurprisingly, this characterisation of the Tupamaros actions contrasted strongly with

their portrayal in military propaganda in which the other, the Marxist or the urban guerrilla (lexical items

that denote difference and foreignness) is represented as breaking the laws and not defending the interests of

the citizens. Achugar argues that *i+n opposition to this, incompetence and foreign interests, the military

appears as the authentic representation of the law and national interests by supporting the constitutional

president and being defined as the last bastion of Orientalidad (authentic national identity). See Mariana

Achugar, Between Remembering and Forgetting: Uruguayan Military Discourse about Human Rights (19762004) (2007) 18 Discourse and Society 521, 529.

13

Woodruff (n 8) 2.

14

Ibid 2.

15

Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South

America, and Post-communist Europe (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1996) 155.

16

Neil J. Kritz, Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies reckon with Former Regimes (United States

Institute of Peace Press, Washington, D.C. 1995) 383.

17

Weschler (n 12) 105.

18

Alexandra Barahona de Brito, Human Rights and Democratization in Latin America: Uruguay and Chile

(Oxford Studies in Democratization, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1997) 40.

19

Weschler (n 12) 106.

20

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 40.

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

Pacheco handpicked a successor as reactionary as himself, Juan Mara Bordaberry, who

became president in 1972.21

President Bordaberry continued and expanded the policies of his predecessor in suspending

civil liberties, banning political opponents and awarding the military increased power. These

moves were similar to that of the Peronist government in Argentina during the early 1970s,

and were in accordance with the Doctrine of National Security that was prevalent across the

Americas in this era.22 In 1973, Bordaberry, under pressure from the military, dissolved

congress and banned some political parties, which marked the effective start of military rule.

However, Bordaberry, a civilian, continued as president until June 1976 when the military,

seeking to discredit him, released a secret memorandum in which he suggested permanent

abolition of all political parties, and the construction of a corporatist and civilian regime,

under his command.23 It appears that the military, which remained rhetorically committed

to democracy, hoped to boost its own legitimacy by ousting the anti-democratic Bordaberry.

The military replaced Bordaberry with a civilian politician from the Blanco party,24 Aparicio

Mndez, who had even less influence over decision-making than his predecessor.25 The

incremental nature of the militarys seizure of power has been labelled as a slow coup,26

and a defining feature of military rule in Uruguay was the extent to which civilians remained

involved in the administration. This is significant as it may have influenced some politicians

attitudes towards amnesty during the transition and has been highlighted in recent efforts to

reinterpret the 1986 amnesty. Indeed, from June 1973 until August 1981, all the presidents

were civilians and civilians headed all government departments, except the Ministries of the

Interior and Defence. Indeed, in its propaganda, the military pointed to the role of civilian

politicians, and in particular, the constitutional president to legitimise its own actions.27

During the Pacheco and Bordaberry administrations, human rights violations against

perceived political opponents were widespread and, at the time of writing, Bordaberry is

under arrest pending trial in Uruguay for his role in multiple murders.28 The abuses of this

21

Weschler (n 12) 106.

For more information on the Doctrine of National Security see J. Patrice McSherry, Predatory States:

Operation Condor and Covert War in Latin America (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham 2005).

23

Charles Guy Gillespie, Uruguays Return to Democracy (1985) 4 Bulletin of Latin American Research 99, 100.

24

This party is also known as the National Party, but for clarity Blancos will be used in this paper.

25

Gillespie (n 23) 100.

26

David Pion-Berlin, To Prosecute and Pardon: Human Rights Decisions in the Latin American Southern Cone

(1994) 16 Human Rights Quarterly 105, 117-8.

27

Achugar (n 12) 534.

28

His arrest was ordered on 16 November 2006. The order relates to the murder of four Uruguayan citizens

(Zelmar Michelini, Hctor Gutirrez Ruiz, Rosario del Carmen Barredo and William Whitelaw) who sought

refuge in Argentina after Bordaberry led a civilian-military coup (together with his former foreign minister Juan

22

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

period meant that by the time the military assumed control in 1973, the security forces

were already organised and mobilised for waging a broadened war against subversion, and

important wartime legal restrictions on the population were already in effect.29 These

conditions meant that many potential spaces for organized resistance were restricted or

eliminated before the coup.30 However, although the military had defeated the Tupamaros

before assuming control, they used the left-wing threat to justify recourse to even greater

repression during their dictatorship.31 Thus, as Barahona de Brito highlights [a]s in

Argentina, human rights abuses of all varieties in Uruguay were especially loathsome since

they continued long after the armed opposition movements had been subdued, and were

thus directed at defenceless citizens.32 Furthermore, as will be discussed below, during the

transition the military and even democratically-elected President Sanguinetti continued to

maintain this narrative by portraying the military as having fought a just war against a

dangerous left-wing threat and therefore as deserving of an amnesty.

The military regime endured until 1985. During this period, Uruguay differed from its

neighbours, as the militarys abuses were primarily acts of torture, rather than killings and

disappearances. These abuses, which the military continually denied, affected large numbers

of Uruguayan citizens, as it is estimated that by the late 1970s, one in 500 citizens were sent

to jail for political reasons, giving Uruguay the highest per capita rate of political prisoners in

the world.33 Indeed, it has also been noted that one in every 47-50 citizens (about 2 per cent

of the population) were detained for interrogation and most were tortured. According to

Loveman, many of those arrested were detained for thought crimes that had been created

through laws that criminalised the intention to commit a crime or to damage the honour

Carlos Blanco Estrad). On 20 December 2006, Bordaberry was charged on ten more counts of murder, and he

has been charged with violating the constitution in carrying out a coup. He was hospitalised with pulmonary

problems on 24 January 2007 and kept under house arrest thereafter. In September 2007, the court ruled that

the charges for violating the constitution exceeded the statute of limitations, but upheld the aggravated

murder charges. See , Uruguay: Former Dictator Arrested Latinnews Daily (17 November 2006).

29

Mara Loveman, High-Risk Collective Action: Defending Human Rights in Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina

(1998) 104 American Journal of Sociology 477, 504.

30

Vania Markarian, Uruguayan Exiles and Human Rights: From Transnational Activism to Transnational Politics,

1980-1984 (2007) 64 Anuario de Estudios Americanos 111, 124.

31

Pion-Berlin (n 26) 110.

32

Ibid 109.

33

Chandra Lekha Sriram, Confronting Past Human Rights Violations: Justice vs. Peace in Times of Transition

(Cass Series on Peacekeeping, Frank Cass, New York 2004) 71. According to the SERPAJ Nunca Ms report

[t]here were two waves of arrests, the first between 1972 and 1974 and the second between 1975 and 1977.

The report further states of those arrested 4,933 persons were convicted by military courts and estimates that

a further 3,700 individuals were imprisoned without trial. Furthermore, some individuals were imprisoned on

multiple occasions. See Servicio Paz y Justicia, Uruguay Nunca Ms: Human Rights Violations, 1972-1985

(Temple University Press, Philadelphia 1992) 65-6.

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

of the armed forces or otherwise threaten the nation.34 Such high rates of victimisation

within a state with a small population, victims can encounter their torturers on the streets of

Montevideo, and other Uruguayan cities.35 Among those detained, some were held for brief

periods, but many were held for years in horrific conditions.36 The political prisoner

population at its peak number of 7,000 prisoners, including 450 women, was believed to

comprise about 1,900 Tupamaros, with the remaining 5,100 prisoners being detained for

their Marxist ideas, for their work among trade unions or simply criticising the government,

which meant that journalists were particularly targeted.37 Among the political parties the

main target of the military repression after the defeat of the Tupamaros was the left-wing

political coalition, Frente Amplio, whose leader, retired General Lber Seregni, was held in

prison for nine years until early 1984.38

A survey of political prisoners, conducted by Servicio Paz y Justicia (SERPAJ), a local human

rights non-governmental organisation (NGO), as part of their Nunca Ms truth-recovery

project, indicated that 99 per cent of prisoners interviewed said they had been tortured.39

Furthermore, according to Julio Csar Cooper, a former member of the armed forces and

torturer, up to 90 per cent of the Uruguayan officers were made to carry out tortures. 40 This

widespread and systematic use of torture has been explored by Pion-Berlin who argues that

[I]nterrogation sessions were devised not only to physically and psychologically

degrade each prisoner but to send a chilling signal to all [the militarys] political

opposition. Torture was the states principal instrument of intimidation. Nearly all of

those who suffered the physical and psychological traumas associated with these

actions were returned to society so they could exhibit to others the horrors of their

ordeals. Moreover, sessions were carefully orchestrated to extract maximum

amounts of information to be used in tracking down other suspects.41

34

Loveman (n 29) 505-6.

Kritz (n 16) 383.

36

For a description of the conditions in the prisons, see Servicio Paz y Justicia (n 33) and Weschler (n 12).

37

Alan Riding, For Freed Leftists in Uruguay, Hidden Terrors New York Times (Montevideo 7 March 1985) 2.

38

Ibid. Unusually for Latin American politics, General Lber Seregni was an army general who founded a leftwing political party, Frente Amplio, and stood for presidential election for this party in 1971. In response to the

military takeover of power in 1973, he joined left-wing protests and as a result was sentenced to 14 years

imprisonment for betraying the army. He was released in 1984 as part of the transition from military rule and

continued to lead Frente Amplio until 1996.

39

Servicio Paz y Justicia (n 33)79.

40

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 48.

41

Pion-Berlin (n 26) 109.

35

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

He further argues that in comparison to Argentina where detentions and torture were often

brief and were soon followed by the murder of the detainee, in Uruguay, doctors attended

the torture sessions, so that the suffering of the detainees could be prolonged in order to

purposefully and consistently break the will of the prisoners in order to acquire

information. In this system, detainees would be brought to the brink of death and then

back again.42 Interestingly, during the early years of the transition, the Uruguayan Medical

Association became the most active professional association in investigating and sanctioning

its members for complicity with the dictatorship.43

Despite these efforts to keep the prisoners alive, 32 persons died as a result of torture44

and the 1985 report of a parliamentary investigation found that 164 Uruguayan citizens

disappeared during military rule, including nine children.45 Among those who disappeared,

only 32 disappeared in Uruguay, whereas 127 disappeared in Argentina,46 under the

auspices of Plan Cndor.47 Similarly, some Argentines were brought into Uruguay to be

disappeared.48 Although these disappearances represent a small fraction of the abuses

committed by the Uruguayan military, to date, much of the efforts to address the militarys

crimes have focused on investigating the fate of these individuals.49

In addition to illegal practices such as torture and disappearances, military repression also

severely undermined the rule of law in Uruguay. Initially during the Pacheco administrations

parliament voted for declarations of the states of emergency and then in April 1972, it voted

in a state of internal war under which the judiciary and the parliament lost all control over

arrests and ordinary courts ceased to have jurisdiction over civilians accused of subversion.

This erosion of the powers of civilian courts was formalised in July 1972 by the Ley de

Seguridad Internal del Estado y Orden Publica. Barahona de Brito argues that [a]ll these

measures were used abusively, far beyond the letter of the law. Their application annulled

42

Ibid 110.

Weschler (n 12) 127.

44

Servicio Paz y Justicia (n 33) 177.

45

Comisin Investigadora Parlamentaria Sobre Situacin de Personas Desaparecidos y Hechos que la

Motivaron, Cmara de Representantes, Informe Final, (16 July 1985).

46

Ibid. The fates of those who disappeared in Uruguay (both Uruguayan and Argentine citizens) were later reinvestigated by the Comisin para la Paz, which will be discussed below.

47

Operacin Cndor was a coordinated, US-backed plan among the military governments that ruled Argentina,

Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay in the 1970s and 1980s, involving cooperation in tracking down,

capturing and eliminating left-wing opponents. See McSherry (n 22).

48

The most high-profile of these cases is the investigation into the disappearance of the family of renowned

Argentine poet, Juan Gelman.

49

Elin Skaar, Legal Development and Human Rights in Uruguay 1985-2002 (2007) 8 Human Rights Review 52,

54.

43

10

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

or rendered ineffective all the procedures established by law to protect human rights and

fundamental freedoms.50 Thus, a democratically-elected parliament voted in a judicial

system entirely controlled by the armed forces that turned into a state-imposed machine of

terror.51

Following the coup, the Armed Forces consolidated the repressive legal framework through

a series of Institutional Acts,52 under which the legal limits on military power were

bypassed ... without ever departing from formal constitutional rule.53 For example, under

Institutional Act No. 8, the independence of the judiciary was severely impaired; the

Supreme Court was made subordinate to the executive, and the court system, in general,

was deprived of its status as a coequal branch of government.54 The military were eager to

legitimise their assumption of power by presenting their actions as being in defence of the

democratic traditions of their country and contrasting them with the illegal actions of the

left-wing guerrillas. This meant that despite the militarys violence suppression of its

opponents, it maintained a rhetorical respect for the rule of law causing it to deny its most

heinous crimes and to reiterate in the fifth Institutional Act of 1976 that human rights were

guaranteed in the country.55 In this context, according to SERPAJs Nunca Ms report, [t]he

rule of law was emptied of content, and wide gaps separated what was said from what was

done, but all came about according to how things were supposed to be done.56 For

example, the military courts maintained a veneer of due process in which the formalities of

trials and the opportunity for a semblance of a defence were visible, but in which secret

hidden documents from the intelligence services were not verified and confessions

extracted under torture were accepted by the courts without further confirmation and

without any other evidence.57 Furthermore, the military judges were bound by the will of

their superiors.58 As with other sectors of civil society, protest against the militarys

assumption of power was muted among the legal profession and the few lawyers who

defended those accused by the regime were themselves persecuted.59 Indeed, there was no

50

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 42.

Servicio Paz y Justicia (n 33) 109-10.

52

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 42.

53

Ibid 41.

54

Martin Weinstein, Uruguay: Democracy at the Crossroads (Westview Press, 1988) 55.

55

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 57.

56

Servicio Paz y Justicia (n 33) 109.

57

Ibid 111.

58

Ibid 111-12.

59

Loveman (n 29), fn 43. For a discussion of the weakness of the judiciary during the dictatorship, see Leon

Cortinas, El Poder Ejecutivo y su Funcion Jurisdiccional: Contribucin al estudio del estado autoritario, del ocaso

de la justicia en Amrica Latina (UNAM, Mexico 1982).

51

11

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

legal association to defend the regimes victims until 1981, when the anti-regime sectors

won the internal elections of the Colegio de Abogados (Bar Association) for the first time

since the coup.60 In addition, Comisin Nacional de Derechos Humanos61 and the Uruguayan

Institute of Legal and Social Studies (IELSUR), founded in 1983 and 1984 respectively, both

began taking human rights cases.62 Furthermore, during the dictatorship, the military courts

did not punish those members of the security forces who were responsible for human rights

violations.63

Finally, the military repression also involved controlling all aspects of the social and political

landscape in Uruguay to the extent that the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights,

described Uruguay under military rule as the closest approximation in South America of the

Orwellian totalitarian state.64 The countrys relatively small territory and small homogenous

population facilitated this repression.65 For example, [a]ll faculty and curricula, from primary

school through university were closely monitored and forced to adhere to the regimes

ideology.66 Furthermore, [e]very adult was investigated and graded on their level of

democratic faith.67 Under this military ideology,

[W]hole categories of individuals and institutions [were] excluded from the

collectivity, as alien to the Nation, its spirit, tradition, well-being and future. Marxism,

Leninism, Socialism and Communism and whoever promoted these ideologies or

merely sympathised with them had to be marginalised or eliminated due to the

threat posed to the Nation and its values.68

This ideological screening resulted in 30,000 civil servants losing their jobs.69 Furthermore,

during the period of military rule, an estimated three to four hundred thousand

60

Markarian (n 30) 122 and Barahona de Brito (n 18) 85.

After SERPAJ, which was founded in 1981, was banned in 1983 it was known briefly as the Comisin Nacional

de Derechos Humanos. At this point it began organising to take human rights cases.

62

Markarian (n 30) 122. According to Barahona de Brito IELSUR founded by lawyers who abandoned the

Colegio in protest against the directorates decision to limit itself to the administrative processing of human

rights cases on behalf of the National Human Rights Commission, began to take on human rights cases in

coordination with SERPAJ from 1984 onwards, only a year before the democratic government took power. See

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 85.

63

An exception to this occurred in 1983 when the 50 officers were tried by the military Tribunales de Honor for

their role in the torture and killing of Dr Vladimir Roslik. See Barahona de Brito (n 18) 96.

64

Cited in Loveman (n 29) 503-4.

65

Ibid 503-4.

66

Kritz (n 16) 383.

67

Ibid 383.

68

Luis Roniger, Human Rights Violations and the Reshaping of Collective Identities in Argentina, Chile and

Uruguay (1997) 3 Social Identities 221, 238.

69

Kritz (n 16) 383.

61

12

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

Uruguayans, of a population that stood at 3 million in 1970, went into exile.70 Although

these sufferings were less violent than the torture and imprisonment, they were also areas

that had to be addressed in the transitional governments human rights policy. Furthermore,

the widespread suppression of political life, combined with the detention of opponents and

the high level of exiles meant that for much of the dictatorship the parties and the social

organisations within Uruguay were unable to respond to the repression and to focus

opposition around the issue of human rights. However, some political opponents mobilised

in exile to campaign for amnesty for political prisoners and the restoration of democracy.71

3. DEMANDS FOR AMNESTY AND POLITICAL CHANGE, 1980-1984

Among Uruguayan exiles, demands for amnesty for political prisoners began early in the

military dictatorship. In 1977, the Secrtariat International de Juristes pour lAmnistie en

Uruguay (SIJAU), was founded in Paris with the support of all the major leftist parties and

groups acting in exile.72 In addition, these exile organisations worked to raise international

awareness of the human rights abuses in Uruguay by bringing the militarys crimes to the

attention of the UN Human Rights Committee, the Organisation of American States and the

International Committee of the Red Cross. These campaigns also received significant support

from international NGOs, such as Amnesty International and the International Commission

of Jurists. The campaigns brought financial and political pressure on the military dictatorship

and contributed to the militarys desire to legitimise its dictatorial rule by rhetorically

supporting democracy. Consequently, in 1977, following Bordaberrys removal from the

presidency, the military announced that it would draft a new constitution to strengthen

democracy, which it would put to the people in a plebiscite in 1980.73

This draft constitution sought to entrench the repressive policies that the military had

implemented through its Institutional Acts and other extralegal measures in numerous ways.

For example, it would have curtailed the legislatures authority to lift a state of emergency,

removed legal safeguards against arbitrary arrest, mandated military courts to try civilians

accused of subversion, and established a legal justification for the bans, political dismissals,

and abuses committed by the dictatorship.74 Furthermore, it would have provided for the

continued direct presence of the armed forces in key decision-making bodies.75 Although

70

Sriram (n 33) 71. See also Markarian (n 30); Vania Markarian, Left in Transformation: Uruguayan Exiles and

the Latin American Human Rights Networks, 1967-1984 (Routledge, 2005).

71

Barahona de Brito (n 2) 582.

72

Markarian (n 30) 120.

73

Linz and Stepan (n 15) 152.

74

Weinstein (n 54) 74.

75

Ibid 75.

13

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

clearly this constitution would have condoned a model of authoritarian democracy, the

militarys decision to put it to a plebiscite illustrated its desire to reach legitimacy and

reconstruct consensus.76

The military was so confident of victory in the plebiscite that they pledged in advance to

respect the results. However, they were disappointed when their draft constitution was

rejected by 57.2 per cent of voters.77 Following their defeat, some prominent military

officers began to question the militarys right to rule. For example, the transcripts of the

constitutional working group that met the day after the plebiscite reveal that some of the

top military officials, for the first time ever, began to refer to the military government simply

as the gobierno de facto.78 Furthermore, the defeat had left the military facing a dilemma:

If they retained power collectively, their hierarchies of command might be disrupted

by internal politicization and bureaucratic capture. If they allowed a strong-man

emerge, they could become chained to his mistakes, alienated by his ambitions, and

ultimately tempted to sacrifice him. Yet the alternative of allowing elections, as

repeatedly promised, left the question of how to prevent Wilson Ferreira, their most

feared opponent, from winning.79

This dilemma appears to have contributed to divergences among the branches of the armed

forces, although the military maintained a united public face. According to Gillespie, the

navy had become largely disillusioned with the proceso, the air force was split, and much

of the army was favour of sustaining military rule, and its generals had an overall majority in

the Junta de Oficiales Generales.80 Furthermore, the justification for continued military rule

had been weakened by the defeat of the left-wing guerrillas, the failure of the militarys

economic policies81 and its increased isolation both domestically and internationally.82

Eventually in 1981, a former army general, Gregorio lvarez was made president, and he

launched a timetable for the restoration of civilian government. This called for a lengthy

transition with the remainder of 1981 being devoted to the elaboration of a law regulating

the political parties; 1982 being the year for the reorganisation of the traditional parties,

76

Luis Roniger and Mario Sznajder, The Legacy of Human Rights Violations and the Collective Identity of

Redemocratized Uruguay (1997) 19 Human Rights Quarterly 55, 60.

77

Munck (n 3) 156.

78

Linz and Stepan (n 15) 152-3.

79

Charles Guy Gillespie, Negotiating Democracy: Politicians and Generals in Uruguay (Cambridge Latin

American Studies, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1991) 108-9.

80

Ibid 109-10.

81

Linz and Stepan (n 15) 153.

82

Weinstein (n 54) 82.

14

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

including the election of party leaders; followed in 1983 by the drafting of a new

constitution by the military and the new party leadership. In November 1984, it was planned

that there would be a plebiscite on this constitution, to coincide with a general election, and

power would be handed to the elected government in March 1985.83 Unlike its Argentine

counterparts, who had been humiliated by their defeat in the Malvinas war, the Uruguayan

military was able to demand such a lengthy transition as it retained considerable power

during the transitional negotiations,84 particularly since it left power of its own accord and

unbowed.85 Indeed, Pion-Berlin argues that

First and foremost, this was a negotiated transition, with the democratic opposition

and the military sitting down at the bargaining table as co-equals. Those negotiations

insured that neither side would enjoy a decisive advantage once the elected

government had been installed. A relative balance of power between two sides

resulted, where neither had a dominant strategy to deploy nor realistic hopes of

imposing its preferred outcomes in the short term.86

Therefore, the military had significant, but not total control over the shape of the future

political landscape.87

Although much political activity had been suppressed under military rule, Uruguayan

political parties were active in voicing their opposition to the proposed military constitution

before the 1980 plebiscite by, for example, smuggling speeches by exiled politicians

denouncing the proposal into Uruguay. Following the militarys defeat, the traditional

political parties emerged from the plebiscite energised, less frightened and newly selfconfident.88 For the most part, they accepted the militarys timetable for the handover of

power and following the passing of legislation in 1982 calling for internal elections to

appoint new leaders in the traditional parties, most parties simultaneously held internal

elections on 28 November 1982 in which voters could select party representatives who

would participate in the negotiations with the military.89 Even supporters of the left-wing

Frente Amplio, which was officially banned, participated by either casting blank ballots to

show their support for their imprisoned leader, General Lber Seregni, or by voting in

support of the partys alliance in exile with the Blanco partys leader, Wilson Ferreira

83

Ibid 76-7.

Ibid 172.

85

Sriram (n 33) 42.

86

Pion-Berlin (n 26) 113-4.

87

Sriram (n 33) 43.

88

Linz and Stepan (n 15) 152-3.

89

Julio Maria Sanguinetti, Present at the Transition (1991) 2 Journal of Democracy 3, 8.

84

15

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

Aldunate.90 The military in a gesture of goodwill in this period gradually began releasing

political prisoners who were not suspected of belonging to the Tupamaros. 91 Nonetheless,

the electorate again voted against the military as opposition sectors obtained a large

majority of the vote.92 Furthermore, during 1982, the first public calls within Uruguay for an

amnesty for political prisoners were made by a minor opposition paper, La Plaza, and the

relatives of the political prisoners sent a signed petition to President lvarez demanding the

release of the prisoners.93 This was one of the first public challenges to the regime over the

issue of human rights violations.94

The unfavourable election results for the military coupled with a further economic slump

forced the military to enter into negotiations with the political parties.95 The 500 elected

representatives of each of the political parties voted for a 15-member party executive, which

then selected delegates to participate in formal negotiations.96 These negotiations, known as

the Parque Hotel talks, began on 13 May 1983 and were conducted under the glare of

publicity. The military, predictably, were particularly concerned with the question of trials

for human rights violations, although there was no direct reference to the issue. Supporters

of President lvarez within the military argued that the military courts should retain

jurisdiction over military personnel, including those accused of human rights abuses, and

over civilians accused of subversion whether in peacetime or wartime. 97 According to

Barahona de Brito, [i]t was largely due to the unwillingness of the parties to accept the

militarys jurisdictional demands that the talks became a dialogo de sordos or a dialogue of

the deaf and then broke down,98 with the Blanco Party pulling out first, followed eventually

by the Colorado Party in July 1983 (the left-wing Frente Amplio was still banned and hence

90

Markarian (n 30) 115. Prior to the negotiations there was a cooperation between Frente Amplio and the

Blanco Party in an exile opposition front, Democratic Convergence, which had helped to unite the two groups

on the issue of human rights violations. This cooperation broke down when Frente Amplio agreed to

participate in the Club Naval talks, despite the continued imprisonment of the Blancos leader, Wilson Ferreira

Aldunate, and the Frente Amplio leader, Lber Seregni. The Blancos, in contrast, refused to take part in the

talks. This breakdown has been argued to have inhibited the development of a consensus on human rights

issues during the transition. See Barahona de Brito (n 2) 587; Americas Watch, Challenging Impunity: The Ley

de Caducidad and the Referendum in Uruguay (1 March 1989).

91

Jimmy Burns, Uruguays Military opens a way back toward Democracy, Christian Science Monitor

(Montevideo 5 March 1982) 5.

92

Markarian (n 30) 115.

93

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 86.

94

Ibid 86.

95

Markarian (n 30) 115.

96

Gillespie (n 23) 103.

97

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 76.

98

Ibid 76.

16

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

did not participate).99 The failure of these talks caused both civilian and military negotiators

to favour private negotiations away from public scrutiny and to deliberately ignore the

human rights issue in future negotiations, in order to avoid derailing the process. 100

The failure of the Parque Hotel talks resulted in increased political tensions. The military

launched a new crackdown on its opponents by issuing a decree temporarily suspending all

public political activity and banning even more politicians.101 The Blanco and Colorado

parties responded by uniting in radical opposition to military rule, together with the

banned left-wing groups. Public protests demanding the release of political prisoners and an

end to military government erupted and on 27 November 1983, at least a quarter of a

million people congregated at the foot of Montevideos Obelisk to hear a proclamation

calling for an immediate return to the 1967 constitution, and free and fair elections open to

all.102 This was the largest political demonstration in Uruguays history and it illustrated a

growing consensus around the question of military repression, however, this consensus did

not extend to demanding military accountability.

During this period, the exile community also continued to mobilise in favour of amnesty for

political prisoners. In particular, SIJAU continued to play a pivotal role by organising

conferences in So Paulo and Buenos Aires in 1983 and 1984 in which European and Latin

American jurists, lawyers, and human rights activists were brought together to discuss the

Uruguayan transition. Following both conferences, the delegates demanded the integral

restoration of democratic conditions, called for amnesty for political prisoners, and urged

debate on the future role of the Armed Forces.103 Furthermore, at the So Paulo meeting

two Uruguayan lawyers, Alejandro and Mercedes Artucio, delivered a paper advancing the

first detailed proposal for amnesty according to both international human rights law and

Uruguayan legal provisions prior to the authoritarian regime.104 They stressed

[T]he comprehensive character of the proposal, which involved the complete

restoration of civil and political rights as well as reparations to the victims of abuses,

... opposed involvement by the military justice, and called for the restitution of all

powers to ordinary judges to prosecute human rights violations.105

99

Gillespie (n 23) 103.

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 77.

101

Gillespie (n 23) 103.

102

Ibid 103.

103

Markarian (n 30) 120-1.

104

Ibid 120-1.

105

Ibid 120-1.

100

17

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

Subsequently, at the Buenos Aires meeting, a representative of SERPAJ called for amnesty

for political prisoners and prosecutions of the armed forces.106 These meetings were also

attended by the representatives of the Uruguayan Bar Association, the relatives of political

prisoners and disappeared, Frente Amplio and the trade unions.107

In April 1984, these external calls for amnesty for political prisoners and accountability for

human rights abuses gained greater media attention and public support within Uruguay

following the arrest and death from torture of Vladimir Roslik, a doctor of Russian descent

from a small town in the interior of Uruguay. Rosliks death was an embarrassment for the

military. However, there were allegations that it was a result of internal plots to discredit

General Medina, commander of the Third Military Region, where the event took place.

Medina, who was in line to become Commander-in-Chief was alleged to have a

commitment to military professionalism and to favour sticking to a timetable for

withdrawal, which caused hardliners to attempt to force his removal by killing Roslik.

However, if this was a deliberate strategy, it was unsuccessful as General Medina became a

pivotal figure in the negotiations, the Colorado Party adopted the banner of human rights,

a wide public consensus emerged against the violation of human rights,108 and the officers

involved in the torture were court martialed, the first time that the military personnel had

been held accountable for human rights abuses.109

4. TOP-DOWN TRANSITION: 1984 PACTO DEL CLUB NAVAL AND LIMITED

PRISON RELEASES

The Roslik Affair appears to have encouraged the military to re-engage directly with

negotiations and the question of releasing political prisoners. On 6 July 1984, to coincide

with start of talks between the military and politicians at the Naval Club, the military

released several political prisoners. Furthermore, during the talks the military pledged to

suggest that the military tribunal review the cases of those prisoners who had served more

than half their sentences, to determine whether some should be freed, which was one of

the main demands of the political parties.110 Subsequently, on 25 July 1984, while the talks

were still ongoing, the president of Uruguays Supreme Military Court announced that the

court would review the cases of over 700 political prisoners, in response to opposition

106

Ibid 122.

Ibid 122.

108

Roniger and Sznajder (n 5) 79.

109

Gillespie (n 79) 140.

110

, Uruguay: Military Court to Review Political Prisoner Cases Inter Press Service (Montevideo 25 July

1984).

107

18

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

demands.111 These moves appear to have been timed to encourage the politicians to make

concessions during the talks. However, excluded from those prisoners who were released

was the leader of the Blanco Party, Wilson Ferreira Aldunate, who had recently been

imprisoned immediately upon his return to Uruguay from exile. His imprisonment meant

that unlike the previous Parque Hotel talks, the Blanco Party refused to participate in the

Club Naval negotiations in protest at the detention of its leader. Instead, the military

legalised the left-wing Frente Amplio to enable it to participate, so the Colorado Party would

not have to take all the responsibility for selling out by reaching an agreement with the

military.112 Other left-wing groups, including the Communists remained banned, and the

leader of Frente Amplio, Lber Seregni, who had been released from prison in March 1984

remained banned from political activity during the talks.113 The Naval Club talks also differed

to those at the Parque Hotel, as they were conducted in total secrecy. This emphasis on

secret elite negotiations marginalised human rights groups, particularly SERPAJ, and popular

mobilisation efforts.114

During these negotiations, the military hardline complained to the junta about the need for

explicit guarantees of non-prosecution to be included in the settlement.115 According to

Barahona de Brito, the junta responded to this pressure by ordering the main military

negotiator, General Medina, to propose an amnesty. However, the Colorado politician and

main civilian negotiator, Julio Mara Sanguinetti, reportedly persuaded General Medina to

refrain from doing this, arguing that to do so would cause the talks to collapse. Therefore,

instead of complying with the juntas demands, Sanguinetti and Medina pre-empted further

pressure from the military hardline by calling a joint press conference to announce the

successful completion of the talks.116

In keeping with the secretive nature of the negotiations, no minutes had been taken during

the talks and no formal document was signed at their conclusion. 117 However, the

negotiating parties implicitly subscribed to Institutional Act No. 19,118 published on 3 August

1984. This Institutional Act outlined the following bases of the accord:

1. Institutional Act No 1 suspending elections was repealed

111

Ibid.

Gillespie (n 23) 104.

113

Weinstein (n 54) 83.

114

Markarian (n 30) 124-5.

115

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 77.

116

Ibid 77-8.

117

Ibid 77.

118

Acto Institucional N 19 (3 August 1984).

112

19

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

2. Army promotions to the rank of commander in chief would be made by the

president from a list of three candidates provided by the generals; for the

other services, from a list of only two candidates

3. The National Security Council would survive in an advisory capacity, meeting

at the request of the president alone, and including a majority of cabinet

ministers over the military

4. At the initiative of the president, Parliament would have the right to vote a

state of insurrection to suspend habeas corpus

5. A protective legal mechanism (recurso de amparo) would allow appeals

against government decisions or military actions

6. Military courts would continue to try civilians only when parliament had voted

a state of insurrection

7. The National Assembly elected in 1984 would act as a constituent assembly to

consider permanent incorporation of the provisions of this last institutional

act into the Constitution

8. If amended, the new text of the constitution would be submitted to plebiscite

in November 1985119

The terms of this Institutional Act illustrate that the pact was agreed between equals as

the military did not succeed in getting the guarantees they initially sought, but the party

representatives were in turn unable to impose a strong break with the authoritarian

institutions.120 For example, the military had given up its long-sought demand for a

National Security Council, and instead, accepted an advisory role in which they would be

outnumbered by civilians.121 In exchange, the politicians agreed to restore the vote to

Uruguays soldiers and policemen, and to repeal a decree that had suspended the immunity

of civil servants from firing, which according to Gillespie, the military had requested in the

the hope of protecting the regimes loyal servants in the future.122 Furthermore, some of

the powers that the military retained under Institutional Act No. 19 were provisional for one

year, and could be abolished or modified by parliament, acting as a constituent assembly

119

Gillespie (n 79) 177-8.

Markarian (n 30) 124-5.

121

Weinstein (n 54) 84-5.

122

Gillespie (n 23) 104.

120

20

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

during its first year in power.123 In this way, much as the militarys assumption of power had

been a slow coup, their removal from government was also gradual. However, according to

Linz, with the agreed upon lapse of the Naval Club Pact, one year to the day after the

inauguration of a democratic parliament, there were no de jure constraints on the policy

freedom of the democratic government,124 although de facto limits remained due to the

militarys continued position of strength. Furthermore, despite the agreement to return to

the 1967 constitution, which formally meant that the military had no greater power than it

had possessed before the breakdown of democracy,125 in practice, under the pact, General

Hugo Medina, the key military figure in the negotiations, remained as armed forces

commander and became Minister of Defence in the civilian government in November

1987.126 In addition, the pact resisted introducing any social or economic changes to society,

and instead, represented the restoration of the pre-authoritarian political system,127 to the

extent that Munck has argued that

There was no democratic revolution initiated in Uruguay in 1985. The tendency

towards continuity applied equally in the economic, political and social arenas. The

predominance of restoration over renewal was clear cut. There is no obvious

hegemonic project emerging from either the dominant or the dominated classes. 128

These limitations in the transformational nature of the agreement caused it to be

denounced by the Blanco party who had not participated in the negotiations. The Blancos

described it as the embodiment of continuismo: the continuation of military rule, and

authoritarian economic policies, behind an electoral facade.129

The most notable exception from Institutional Act No. 19 is the omission of any reference to

amnesty or accountability for human rights violations. As discussed above, the negotiators

had learnt from the failure of the Parque Hotel talks that forcing the issue would result in the

collapse of the negotiations. This reluctance to engage with the legacy of the human rights

abuses not just enveloped Sanguinetti and Medina, but also encompassed the left-wing

Frente Amplio, which had only recently joined the negotiation process. Although some

radical left-wing groups which were part of Frente Amplio, notably the Communists and the

Partido por la Victoria del Pueblo (whose members had suffered disproportionately from

123

Weinstein (n 54) 84-5.

Linz and Stepan (n 15) 159.

125

Barahona de Brito (n 2) 586.

126

Pion-Berlin (n 26) 114.

127

Markarian (n 30) 124-5.

128

Munck (n 3) 174.

129

Gillespie (n 23) 104-5.

124

21

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

military repression) had long campaigned for investigations and punishment of human rights

violators, the negotiating sectors - the majority of the left - preferred to avoid a strong

position on these matters,130 preferring to focus instead on the release of political prisoners

and the restoration of civil and political rights.131 Their reluctance has been credited to both

a fear of derailing the negotiations and a desire to position Frente Amplio as a credible

political option in the elections by embracing a conciliatory approach that precluded strong

human rights claims from their immediate platform.132

Although the manoeuvres by Sanguinetti and Medina meant that the military had agreed to

hand over power to elected politicians without first gaining a formal guarantee that they

would not be held accountable before civilian courts, the politicians had also not sought a

clear acceptance from the military that there would be prosecutions of human rights

violators. Indeed, immediately after the end of the talks, Medina gave a press conference

stating that

[T]he Armed Forces were ready to accept justice over those elements which form a

part of the ranks that have demonstrated dishonesty or over elements which are in

the ranks that acted on their own account; but for those that acted on orders or on

the command of a superior, those will deserve our greatest backing.133

He also claimed that the normal changes in the jurisdiction of the Military Justice system

and the Civil Justice system will not affect the army or its members.134 These statements

indicate that the military was only prepared to accept accountability for those members

whom it deemed to have acted dishonestly, but that it would not accept accountability for

perpetrators of human rights violations who had been obeying orders.135

Since the agreement of the Naval Club Pact, there has been much speculation that General

Medina and future president Sanguinetti had in fact reached a gentlemans agreement that

the civilian government would refrain from prosecuting the military for their human rights

violations, although it would not prevent civilians bringing legal proceedings.136 It is alleged

that this agreement was intended to provide the military with an effective amnesty.137

Barahona de Brito has suggested that Sanguinetti was willing to make such an agreement

130

Markarian (n 30) 128.

Barahona de Brito (n 18) 90.

132

Markarian (n 30) 117.

133

Cited in Barahona de Brito (n 18) 78.

134

Ibid 78.

135

Roniger and Sznajder (n 76) 75.

136

Sriram (n 33) 43.

137

Roniger and Sznajder (n 76) 72; Americas Watch (n 90).

131

22

Uruguays Evolving Experience of Amnesty 2009

and Civil Societys Response

due to the close ties between the military and Sanguinettis Colorado party138 and the close

personal relationship of Sanguinetti and Medina.139 Indeed, writing in 1991, Sanguinetti

himself referred to importance of developing relationships during the long negotiation

process:

In Uruguay there was a gradual transition through negotiations, which was very

important. Why? Because the dialogue between the political and military leaders

permitted us to get to know each other. The politicians learned to understand

military reasoning, and the military learned to negotiate and compromise. From 1980

to 1984 we talked, argued, left the negotiating table, returned again, and finally

agreed to hold elections. This was a very significant asset for us in our transition

process, one which was lacking in countries like Argentina, where democracy was

restored with no period of debate or negotiation.140

As was explored above, the close ties between the military and the Colorado Party predated

the militarys seizure of power in 1973 as members of the Colorado Party were implicated in

the militarys crimes during the Pacheco and Bordaberry regimes, and also through the

involvement of civilian politicians in the civico-military period. As such, right-wing elements

of the Colorado Party may have been supportive of such a tacit agreement with the military

for fear of implicating themselves or their colleagues. In addition, General Medina tried to

justify to the military hardline his failure to demand an explicit amnesty by arguing that to

have done so would have been tantamount to admitting guilt,141 whereas leaving without an

amnesty allowed the military to hand over power with honour, which is what we had hoped

for.142 The existence of such a pact, although widely believed, has consistently been denied

by all parties to the negotiations. According to Weschlers detailed account of this period,

for a while, Sanguinetti maintained in interviews that the subject hadnt even come up. In

138

The Colorado Party, which was to lead the democratic government, had become increasingly authoritarian

in the mid-sixties, and from 1973 onwards, it had participated in the military government. See Barahona de

Brito (n 2) 583.

139

Alexandra Barahona de Brito, Truth, Justice, Memory and Democratization in the South Cone in Alexandra

Barahona de Brito, Carmen Gonzlez Enrquez and Paloma Aguilar Fernndez (eds), The Politics of Memory:

Transitional Justice in Democratizing Societies (Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001) 129-30.

140

Sanguinetti (n 89) 7.

141

Gillespie (n 79) 176.

142