Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Rs CHP PR Links Among High

Transféré par

Ferdina NidyasariTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Rs CHP PR Links Among High

Transféré par

Ferdina NidyasariDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Links Among High-Performance

Work Environment, Service Quality,

and Customer Satisfaction: An

Extension to the Healthcare Sector

Dennis J. Scotti, Ph.D., FACHE, FHFMA, the Alfred E. Driscoll Professor of

Healthcare and Life Sciences Management, Fairleigh Dickinson University, New

Jersey; Joel Harmon, Ph.D., professor of management and research director, Institute

for Sustainable Enterprise, Fairleigh Dickinson University; and Scott J. Behson,

Ph.D., associate professor and chair, Department of Management, Fairleigh Dickinson

University

[First Page]

[109], (1)

Lines: 0 to 40

................................................................................................

E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y

Healthcare managers must deliver high-quality patient services that generate highly

satised and loyal customers. In this article, we examine how a high-involvement

approach to the work environment of healthcare employees may lead to exceptional service quality, satised patients, and ultimately to loyal customers. Specifically, we investigate the chain of events through which high-performance work

systems (HPWS) and customer orientation inuence employee and customer perceptions of service quality and patient satisfaction in a national sample of 113

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) ambulatory care centers. We present a conceptual model for linking work environment to customer satisfaction and test

this model using structural equations modeling (SEM). The results suggest that

(1) HPWS is linked to employee perceptions of their ability to deliver high-quality

customer service, both directly and through their perceptions of customer orientation; (2) employee perceptions of customer service are linked to customer

perceptions of high-quality service; and (3) perceived service quality is linked

with customer satisfaction. Theoretical and practical implications of our ndings,

including suggestions of how healthcare managers can implement changes to their

work environments, are discussed.

For more information on the concepts in this article, please contact Dr. Scotti at

prof djs@fdu.edu. Work on this project was partly supported by a grant from the U.S.

National Science Foundation (NSF), Innovation and Change Division. Conclusions do

not necessarily represent the views of the NSF. We acknowledge the Veterans Health

Administration (VHA) Ofce of Quality and Performance for providing data used in

this study. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of

the Department of Veterans Affairs, the VHA, or the United States government.

109

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 109

1st proof

0.33304pt PgVar

Normal Page

* PgEnds: Eject

[109], (1)

Journal of Healthcare Management 52:2 March/April 2007

healthcare industry. We investigated the

chain of events through which aspects

of work climate, specically highperformance work systems (HPWS)

and customer orientation, inuence

employee and customer perceptions

of service quality and their ultimate

impact on patient satisfaction in 113

Veterans Health Administration (VHA)

centers.

The roles of HPWS and customeroriented work climates as catalysts for

superior service quality and increased

patient satisfaction have received little

empirical investigation within the

healthcare environment. This study

offers empirical justication for the

dimensions of the work environment

that contribute to high performance in

a healthcare setting and yields ndings

that can be used to guide healthcare

managers in their efforts to design and

enhance their organizational practices.

In the following sections, we provide the theoretical foundations of

our linkage model, dene the constructs and measures used, present

our results, and discuss the practical

implications and limitations of our

research.

ealthcare managers seek to improve

overall system effectiveness by

strengthening their value chain, thereby

increasing customer retention and

market share. Better knowledge of

conditions in the work environment

that drive service quality excellence

and customer satisfaction is valuable to healthcare managers. It is

becoming clear that strategic human

resource practices that result in highperformance work environments are

linked with important organizational

outcomessuch as service quality,

customer satisfaction, and loyaltyin

a wide variety of commercial industry

contexts (Dean 2004). Evidence also is

accumulating that customer-oriented

work climates produce superior service

quality and customer satisfaction,

operating independently (HenningThurau 2004) or in conjunction with

high-performance human resource

practices in proprietary rms in retail

services industries (Schneider, White,

and Paul 1998; Yoon, Beatty, and Suh

2001).

In contrast, the mission, design,

and resource constraints of health

services organizations may differ meaningfully from those of rms operating

in the broader services domain, and

many health services providers are

public or not-for-prot entities, rather

than for-prot enterprises. It should

be noted, however, that the existence

and magnitude of such differences may

be anchored more in a priori beliefs

than empirical evidence (Rainey and

Bozeman 2000). The goal of this study

is to determine whether the research

evidence regarding the importance of

work climate can be extended to the

T H E O R E T I C A L F O U N D AT I O N

Linkage research examines and tests

the chain of events that is set into

motion when a strategic or operational intervention is introduced by

management. The origins of linkage

research are rooted in the research of

Benjamin Schneider and his coinvestigators, who demonstrated that employee perceptions of human resource

practices were connected to customer

perceptions of their service experience

110

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 110

1st proof

[110], (2)

Lines: 40 to 59

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[110], (2)

High-Performance Work Environment, Service Quality, and Customer Satisfaction

involvement, empowerment, trust, goal

alignment, training, teamwork, communications, and performance-based

rewards. Organizations that provide

enabling work environments will have

employees who can devote their efforts

to meeting the needs and expectations

of customers, thereby improving service

quality (Pugh et al. 2002; Schneider

and Bowen 1985). The work of prior

investigators offers compelling empir[111], (3)

ical evidence that bundling complementary sets of human resource practices closely resembling HPWS (e.g.,

Lines: 59 to 71

facilitative management, resources,

training, communications, teamwork,

0.0pt PgVar

aligned goals, and rewards) positively

affects employees perceptions of their

Normal Page

ability to deliver high-quality services

* PgEnds: Eject

to their customers in a variety of forprot, retail service settings, including

[111], (3)

insurance (George 1990; Hallowell,

Schlesinger, and Zornitsky 1996), banking (Schneider, Parkington and Buxton

1980; Schneider and Bowen 1985), and

telecommunications (Batt 2002). In the

healthcare context, nurse perceptions

of their ability to serve patients have

been conceptually linked to their work

conditions (Newman, Maylor, and

Chansarkar 2001), and employee development practices have been empirically

connected with hospital staff productivity (Goldstein 2003). Accordingly, the

assumed connection between HPWS

and employee perceptions of service

quality occupies a root position in our

posited chain of linkages.

Customer orientation is dened

as the importance that service providers

place on their customers needs and

expectations relating to a rms service

offerings (Kelly 1992). A compre-

in retail banking. James Heskett and

his collaborators added momentum

and depth to the genesis of linkage research by extending Schneiders models

to include an emphasis on customer

loyalty and protability (see Pugh et

al. 2002 and Dean 2004 for excellent

overviews of the subject). Despite

considerable progress in specifying

and empirically testing various linkage

models, the specic matrix of strategic

human resources management (HRM)

practices that drive the chain reaction

remains unsettled. Progress may lie in

adopting a systems view of HRM that

considers the overall conguration of

HRM practices that best t particular strategies (e.g., enhancing service

effectiveness), rather than examining

the effects of individual practices on

organizational performance (Bowen

and Ostroff 2004). Extending our

understanding of how such an array

of HRM practices may interact with

the creation of a customer-oriented

work climate to spur the chain reaction

is also desirable. Figure 1 shows the

conceptual model to be tested in the

present study. Next, we discuss the

theoretical and empirical underpinnings associated with each path in our

model.

Linkages Among HPWS, Customer

Orientation, and Employee Perceptions of

Service Quality

HPWS, also referred to in the literature

as high-involvement work systems

and high-performance organizations

(Nadler and Gerstien 1992; Lawler,

Mohrman, and Ledford 1995), represents an interrelated and aligned

set of core characteristics, including

111

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 111

1st proof

Journal of Healthcare Management 52:2 March/April 2007

FIGURE 1

Conceptual Model

[112], (4)

Lines: 71 to 91

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

hensive commitment to total quality

would involve service-enabling HRM

practices and a focus on customers.

Schneider and Bowen (1993) found a

link between human resource practices

and customer service orientation and

also found that both were related to

employee and customer perceptions

of service quality. They concluded

that service-enabling HRM practices

and a service-oriented climate were

distinct but interrelated organizational

dynamics. Consequently, customer orientation can be viewed as a construct

that partially mediates the linkage between HPWS and perceptions of service

quality. We, therefore, hypothesize

(as shown in Figure 1) that HPWS

will affect employee perceptions of

service quality both directly (H1) and

indirectly via its effects on (H2) and

through (H3) customer orientation

(i.e., a mediated effects model).

Links Among Employee Perceptions of

Service Quality, Customer Perceptions

of Service Quality, and Customer

Satisfaction

Common among linkage research

studies is the merging of data collected

from employees and consumers, with a

particular focus on assessing the degree

of congruence between each groups

attitudes toward service quality. Various

studies have shown an association between employee and customer perceptions of service quality delivered and

received in commercial retail service

settings (Schneider, Parkington, and

Buxton 1980; Schneider and Bowen

112

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 112

1st proof

[112], (4)

High-Performance Work Environment, Service Quality, and Customer Satisfaction

1985). A link between employee and

patient perceptions of service also was

observed in a study of hospital inpatient encounters (Nelson et al. 1989).

This connection is supported by the argument that service providers, by virtue

of their close contact with customers,

are reliable commentators on consumer

needs and expectations (Hennig-Thurau

2004). The simultaneous provision and

receipt of healthcare in a high-contact,

face-to-face, professional-service context

obscures the boundary between employee and customer/patient. Patients

must participate in the care delivery

process and are often cocreators of

their own service. Therefore, the perceptions of employees and customers

regarding service quality are rooted in a

common foundation.

The role of customer perceptions

of service quality as an antecedent of

overall customer satisfaction has been

extensively researched and is widely

accepted in the services marketing literature (Anderson, Fornell, and Lehmann

1994; Churchill and Surprenant 1982;

Cronin and Taylor 1992; Rust and

Oliver 1994). More recently, evidence

has emerged supporting the existence

of a causal connection between service

quality perceptions and patient satisfaction judgments in the healthcare

context (Bigne, Moliner, and Sanchez

2003; Marley, Collier, and Goldstein

2004; Woo et al. 2004). As a result,

there is ample theoretical and empirical

justication to hypothesize afrmative

links between employee-perceived and

customer-perceived service quality (H4)

and between customer-perceived service

quality and customer satisfaction (H5)

as the terminal path in our model.

Finally, we are interested in the

link between customer satisfaction and

customer loyalty. Conventional logic

argues that a customer who is satised

with the quality of services received

will be more likely to declare intentions

to engage in repeat consumption.

Although evidence exists to support

this premise in commercial retail rms

(Hallowell 1996; Rust and Zahorik

1993) as well as in outpatient services

rendered by not-for-prot hospitals

(Baker and Taylor 1997), the link between customer satisfaction and loyalty

has not been consistently established in

the literature. Several studies suggest

that we should be cautious about

assuming linkage between customer

satisfaction and loyalty (Dean 2004).

The factors that inuence customer

satisfaction may differ from those that

determine customer loyalty (Reichheld

1996). Moreover, behavioral intentions

expressed at the point of service may

not reliably predict actual behavior

(Storbacka, Strandvik, and Gronroos

1994).

In light of the fact that this is a

study involving the Department of

Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare network, in which U.S. service veterans

receive free healthcare, we felt that

incorporating customer loyalty into

our model was inappropriate. The rest

of our model should be applicable

to private and for-prot healthcare

organizations, but customer loyalty in

a publicly funded free service would

probably not yield generalizable information. For this reason we do not

include loyalty in our model, but the

nature and strength of its connection

113

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 113

1st proof

[113], (5)

Lines: 91 to 98

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[113], (5)

Journal of Healthcare Management 52:2 March/April 2007

with customer satisfaction is discussed

later when we present our results.

METHODS

Study Participants and Procedure

This study is part of an ongoing research project with the VA and is focused on how changes to the work

environment can affect quality and

customer service. The research reported

here draws on responses from an existing 2001 VHA survey of its employees

and from an existing 2001 VHA customer service survey of its patients.

A total of 74,662 responses to the

condential and anonymous employee

survey (72 percent response rate) were

received from employees in 147 VHA

medical facilities across the United

States. Of the 71,526 respondents that

provided demographic information, 56

percent were professional and technical

staff (versus administrative and backofce workers), the overwhelming majority of whom (approximately 89 percent) were clinical personnel, primarily

nurses and technical support staff. This

survey asked for employee observations

and opinions on a wide variety of topics regarding their work experiences.1

However, a wave of recent VHA reorganizations introduced unreliability in

matching various types of data at the

facility level. Therefore, we conned

our analyses only to those facilities

for which employee survey data could

be reliably paired with other facility

data for 2001. This yielded usable data

from 113 VHA facilitiesspecically,

responses of 59,464 employees. We

then aggregated the data by averaging

the individual responses for each item

within each of the 113 VHA facilities.

Our data collection procedure closely

matches that described in Harmon et

al. (2003).

We also used responses from an

existing 2001 VHA customer service

survey of its ambulatory care patients

at those same 113 facilities. This customer survey followed a stratied,

random sampling design that resulted

in a total of 212,874 respondents (an

average of approximately 5.8 percent

of the total ambulatory care patients of

these facilities; with samples ranging

from 478 customers of the smallest

facility to 10,608 customers of the

largest). This survey asked for customer

observations and opinions on a wide

variety of topics regarding the care

they received at the VHA.2 We then

aggregated the data by averaging the

individual responses for each item

within each of the 113 VHA facilities.

Study Measures and Analysis

Independent Variables

The measure we used to assess

strategic human resource practices,

HPWS, is a ten-item scale derived from

the VA employee survey that has been

previously tested and validated (see

Harmon et al. 2003 for a fuller explanation of how this scale was derived

and validated through a series of conrmatory factor analyses). These items

asked employees to what degree they

believed that their workplace exhibited

the characteristics commonly associated

with high-performance work practices

(goal alignment, communication, involvement, empowerment, teamwork,

training, trust, creativity, performance

enablers, and performance-based rewards). Responses to all employee

114

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 114

1st proof

[114], (6)

Lines: 98 to 117

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

* PgEnds: Eject

[114], (6)

High-Performance Work Environment, Service Quality, and Customer Satisfaction

TA B L E 1

High Performance Work Systems Construct Items

Item

Mean S.D.

1.

2.61

Employees are rewarded for providing high quality products and services

to customers.

2. Managers let employees know how their work contributes to the

organizations mission and goals.

3. Employees are kept informed on issues affecting their jobs.

4. Sufcient effort is made to get the opinions and thinking of people who

work here.

5. Employees have a feeling of personal empowerment and ownership of

work processes.

6. A spirit of cooperation and teamwork exists.

7. There is trust between employees and their supervisors/team leaders.

8. I am given a real opportunity to improve my skills in the organization.

9. I feel encouraged to come up with new and better ways of doing things.

10. Conditions in my job allow me to be about as productive as I could be.

0.24

3.04 0.18

3.09 0.19

2.70 0.20

2.61

0.19

3.08

2.85

3.19

3.10

3.15

0.18

0.19

0.17

0.16

0.13

survey items were made on a Likerttype scale, with 1 as strongly disagree,

and 5 as strongly agree. Table 1 lists

these ten items along with their facility

means and standard deviations. The

ten-item scale exhibited a Cronbachs

alpha3 estimate of reliability of .97.

Customer orientation was measured

by three items from the VHA employee survey that assessed the degree to which employees believed

their organization was geared toward

accommodating its customers: (1)

Products, services and work processes

are designed to meet customer needs

and expectations; (2) Customers

are informed about the process for

seeking assistance, commenting, and

or complaining about products and

service; and (3) Customers have

access to information about products

and services. The Cronbachs alpha

estimate of reliability for this vepoint, three-item scale was .95.

Employee-perceived service quality

(Employee PSQ) was measured with

a two-item scale derived from the employee satisfaction survey that reects

employees ability to deliver highquality customer service at their workplace. The two items were (1) How

would you rate the overall quality of

work done in your work group? and

(2) Overall, how would you rate the

quality of service provided to veterans

by your facility or ofce? The Cronbachs alpha index of reliability for this

two-item, ve-point scale was .85.

Dependent Variables

Customer-perceived service quality

(Customer PSQ) was measured with

a two-item scale derived from the

customer satisfaction survey. The two

115

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 115

1st proof

[115], (7)

Lines: 117 to 159

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[115], (7)

Journal of Healthcare Management 52:2 March/April 2007

items (both on ve-point response

scales ranging from poor to excellent) were (1) Overall, how would

you rate the quality of your most recent visit? and (2) Overall, how

would you rate the quality of care

you have received over the past two

months? The Cronbachs alpha index

of reliability for this two-item, vepoint scale was .98, indicating high

levels of item intercorrelation and scale

reliability.

Customer satisfaction was measured

by a single item from the VHA customer survey: All things considered,

how satised are you with your healthcare in the VA? (1 as completely

dissatised and 7 as completely

satised). Although it is often assumed that multiple-item (or scale)

measures of satisfaction are preferred,

recent evidence suggests that singleitem measures of global satisfaction are

as good or better (Nagy 2002; Wanous,

Reichers, and Hudy 1997).

Preliminary data analysis was conducted using the SPSS 12.0 software

package, and hypotheses were tested

using the AMOS 5.0 software package for structural equations modeling

(SEM). Structural equations modeling

offered us two distinct advantages

over traditional regression techniques:

(1) SEM allowed us to simultaneously

calculate both direct and indirect effects

of the independent variables, and (2)

SEM provided us with statistical tests to

determine the relative t to the data

of our hypothesized model against

alternative models and hypotheses

(Schumaker and Long 1996).

R E S U LT S

Table 2 depicts the correlations between the measures used in this study,

along with their means and standard

deviations. The results of the SEM

analyses are presented in Figure 2. As

can be seen, the results provide support

for our hypotheses that (1) HPWS is

linked to employee perceptions of

their ability to deliver high-quality

customer service, both directly (H1)

[116], (8)

and through their perceptions of customer orientation (H2 and H3); (2)

employee perceptions of customer serLines: 159 to 182

vice is linked to customer perceptions

of high-quality customer service (H4);

0.0pt PgVar

and (3) perceived service quality is

linked with customer satisfaction (H5).

Normal Page

Further, the overall t for the structural * PgEnds: Eject

equations model (chi-square of 6.9,

df = 5; p > .05; CFI = .99; RMSEA =

[116], (8)

.06) is excellent, indicating that this

model accurately reects the underlying

data and that no signicant indirect or

direct effects are present in the model

except those that are hypothesized.

HPWS had a strong direct effect

( = .74) on employee perceptions of

whether the organization is oriented

toward customer service. Further, HPWS

had both a direct effect ( = .21) on

employee perceptions of being enabled to provide high-quality customer

service and a total path effect on this

variable (i.e., both direct and indirect

through the customer-orientation path)

of = .60.

We also found a signicant relationship ( = .66) between employee

perceptions and customer perceptions

of service quality. Further, 44 percent of

the variance in customer perceptions

of service quality can be explained by

116

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 116

1st proof

High-Performance Work Environment, Service Quality, and Customer Satisfaction

TA B L E 2

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefcients for Study Variables

Variable

Mean

S.D.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

2.90

3.59

4.16

3.83

5.69

0.17 (.97)

0.13 .74* (.95)

0.13 .60* .68* (.85)

0.14 .29* .37* .66* (.98)

0.13 .14

.25* .50* .73* n/a

High-performance work systems (15)

Customer orientation (15)

Employee-perceived service quality (15)

Customer-perceived service quality (15)

Customer satisfaction (17)

Notes:

1. * denotes that the correlation is statistically signicant at p< .05

2. Scale reliabilities (Cronbachs alpha) are listed in parentheses on the diagonal.

3. Sample size for all correlations is 113 facilities.

[117], (9)

knowing the employees perceptions.

Finally, as expected, customers perceptions of service quality is a strong

driver of their satisfaction, with a direct

effect of = .73. Fully 53 percent of

the variance in customer satisfaction

can be explained by the other variables

in the model.

Considered collectively, a signicant portion of customer satisfaction

can be explained through employee

perceptions that managers at their

facilities empower employees and

create a positive enabling environment

for them to deliver high-quality customer service. HPWS were found to

have a total path effect on customer

satisfaction of = .29. This means

that all the ripple effects of HPWS

on customer orientation and employee

and customer perceptions add up to a

sizeable effect. Specically, our results

show that for every 1 standard deviation increase in HPWS (i.e., from the

50th percentile to the 84th percentile),

a facility will show an associated .29

standard deviation increase in customer

satisfaction.

Lines: 182 to 220

Several post-hoc analyses were

0.0pt

PgVar

performed to supplement the SEM

model. First, computational limitations

Normal Page

prevented us from adding specic

* PgEnds: Eject

service attributes that may have contributed to formation of quality percep[117], (9)

tions directly to the model. However,

supplemental analysis revealed the

strongest correlates of Customer PSQ

were courtesy/respect, condence/trust

in provider, communication, and clinic

efciency (r = .70, .53, .53, and .50,

respectively; p < .05 for all). These

ndings are largely consistent with

those obtained from a study of hospital

inpatients conducted by Scotti and

Stinerock (2003). Second, because of

generalizability concerns, we did not

add customer loyalty directly to our

model. However, we did nd a strong

correlation (r = .73, p < .001) between

customer satisfaction and patients

responses to the following question

that closely maps customer loyalty:

If you could have free care outside

the VA, would you choose to come

here again (1 as denitely would

not, and 4 as denitely would).

117

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 117

1st proof

Journal of Healthcare Management 52:2 March/April 2007

FIGURE 2

Results of the Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

[118], (10)

Lines: 220 to 245

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[118], (10)

Notes:

1. All path coefcients are statistically signicant at p< .05

2. VAF is variance accounted for

3. The model presented in Figure 2 represents a good t to the data. Specically, the following

statistics are all indicative of goodness of t: (1) the chi-squared for the model is 6.921 with

5 degrees of freedom (p = .23; with nonsignicance, p > .05), indicating that the model is not

statistically different from a perfect-tting model); (2) the CFI index is .99 (values over .90 indicate good t); (3) the NNFI (Tucker-Lewis index) is .98 (values over .90 indicate good t); and

(4) the RMSEA is .06 (values at or below .08 indicate good t).

Third, using a measure of average treatment cost reported in Harmon et al.

(2003), we found that patient resource

consumption was negatively correlated

with perceived service quality (r = .23,

p < .05) and satisfaction (r = .30, p

< .01). In other words, facilities with

higher customer-perceived service quality and customer satisfaction tended to

also have lower treatment expenditures.

Lastly, it should be noted that we ran

the SEM model with patient count

included as a covariate to determine

whether the size of the facility affected

the relationships in the model. We

found that patient count had a nonsignicant relationship with patient

perceptions of service quality, did not

account for additional variance in the

model, and did not change the values

of any of the hypothesized paths between constructs. Thus, we can be condent that the relationships we found

apply to facilities of varying sizes.

118

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 118

1st proof

High-Performance Work Environment, Service Quality, and Customer Satisfaction

DISCUSSION

Contributions of the Study

We are aware of no published studies

that have empirically veried the entire

chain of effects from organizational

practices to service quality to customer

satisfaction in a healthcare setting.

The linkage model tested in our study

offers convincing statistical support for

the substance and sequence of events

that connect organizational practices

with patient attitudes. Moreover, the

study underscores and adds empirical

weight to the role played by service

quality as a variable that integrates

the connections between organizational and consumer behavior within

a healthcare context.

The relationship between HPWS

and cost efciency was established in

a recent study using VHA facilities as

the research setting (Harmon et al.

2003). Our investigation extends this

research by demonstrating a strong link

between HPWS and patient perceptions of service quality and satisfaction

using a similar set of VHA facilities.

Further, we found in this study that

enhancing service quality and customer

satisfaction, rather than inating costs,

contributed to cost efciency. We have

also shown that the inuence of HPWS

on customer outcomes is partially

mediated by customer orientation

and is fully mediated by employees

perceptions of the quality of service

they are capable of delivering.

Prior research on the determinants

of patient satisfaction has focused

on inpatient encounters. Our study

focuses on ambulatory care centers, a

setting that has received relatively little

attention, notwithstanding the fact that

the majority of healthcare is delivered

on an outpatient basis. To the extent

that most HRM practices and customer

service attitudes examined in this study

hold relevance to inpatient services

as well, we have reason to believe the

results should be transferable to acute

care rendered to conned patients.

Implications for Managers

The ndings reveal that specic sets of

managerial practicesHPWS and customer orientationfunction as engines

that propel the evolution of a work environment in which the perceptions of

employees are aligned with the service

experiences they provide to patients

and translate into enhanced patient

satisfaction. The interrelated practices

constituting HPWS and customer orientation represent organizational factors

that are amenable to direct managerial

intervention and control in implementing a competitive service strategy for

high-contact healthcare encounters.

To foster a high-performance work

environment with a strong customer

orientation, the importance of customer service must be incorporated

into the mission statement. Management must continuously emphasize the

importance of customer service, clearly

dene customer service objectives, and

solicit input from patients regarding

their perceptions of service encounters.

Once achieved, a customer-oriented

work environment must be reinforced

by strategic HRM practices that nurture a high-performance climate of

service excellence. Several managerial

actions are conducive to cultivating

customer-oriented high-performance

work systems.

119

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 119

1st proof

[119], (11)

Lines: 245 to 258

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[119], (11)

Journal of Healthcare Management 52:2 March/April 2007

The service climate of a healthcare

organization is determined by the people that it hires. Accordingly, the centrality of customer service to the organizations mission should be reected

in job advertisements, job descriptions,

and job interviews (Crotts, Dickson,

and Ford 2005). After the process of

recruitment and selection of service

employees is complete, managers must

continue to inculcate a strong sense of

service responsibility through orientation and training programs; senior

managers should be present at these

sessions to add visible credibility to

and emphasize the importance of

service excellence. Once hired and

acculturated, service providers must be

empowered to address, and if possible

to resolve, patient complaints on a

real-time basis, while being recognized

and rewarded for doing so. Naturally,

reasonable limits should be imposed

on such empowerment to preserve an

appropriate balance between clinical

discipline and patient comfort.

A willingness to listen to the customer is one of the dening features

of a customer-oriented work climate.

Having heard the voice of the customer, health services managers should

promptly communicate information

needed to help healthcare providers

improve their level of service quality.

Our study supports the argument that

service providers, by virtue of their

frequent and close contact with patients, are reliable sources of insight

into the needs and expectations of their

customers. Managers should explicitly

acknowledge this truth and survey the

opinions of front-line providers as

part of their regular market research

activities.

We invite the managers attention

to the importance of team building.

Based on her study of surgical inpatients, Gittell (2002) found that

relational coordination (analogous

to teamwork) among service providers

is most likely to inuence customer

satisfaction and loyalty in settings

where the provider-client interface

is characterized by reciprocal interdependence between tasks, high levels of operational uncertainty, and

time-constrained demands for service

delivery. Health services organizations clearly exhibit these characteristics; therefore, the need for managers to foster a spirit of teamwork

and interdepartmental cooperation is

paramount.

Early strides toward elevating customer service will be short-lived if performance is not properly reinforced. A

percentage of pay and bonuses should

be based on the accomplishment of

service objectives, and a clear message

should be communicated to front-line

employees that promotions will be

predicated on customer satisfaction.

If bonuses are to be awarded based

on team performance, then the team

members should be involved in hiring

decisions that will affect their group.

We conclude by pointing out that

managers must measure progress along

the way, recognizing that changing

their organizations work environment

takes time and dedicated effort.

Limitations of the Study

Several limitations of our ndings

should be acknowledged. First, even

120

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 120

1st proof

[120], (12)

Lines: 258 to 271

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[120], (12)

High-Performance Work Environment, Service Quality, and Customer Satisfaction

though considerable diversity existed

across the VHA facilities involved in

this study, all the organizations are part

of a single, large, government organization. The extent to which similar results

would be obtained in the private sector

remains unclear. Second, employee and

customer perceptions were conveniently

obtained from existing survey data.

Even though the face, content, and

construct validities of our survey-based

measures appeared to be very good, the

measurement instruments themselves

were not specically constructed with

the studys purposes in mind, and a

separate validation study of the HPWS

measure was not performed before

the analyses. Third, HPWS and service

quality were assessed solely through

perceptual measures, which are subject

to assessors distortions, rather than

through more objective indicators.

Although it can be argued that how

employees perceive work practices may

be the most valid measure to use for

this line of inquiry, and that employees

and customers are subject-matter experts on service quality, we are unable

to conrm with this study how well

these perceptions reect reality. Finally,

the research design advises caution in

drawing inferences about causality, because multiple, time-ordered perceptual

measures necessary to establish causal

relationships were not used.

Future Research

We advocate further research that examines linkages in acute care inpatient

settings as well as research comparing

results in public healthcare systems

(e.g., the VHA, state and municipal

systems) with those obtained in notfor-prot and for-prot healthcare organizations. While most of the variables

specied in our model are relevant to a

range of settings, the discrete linkages

quite likely vary in strength. Furthermore, future research should seek

to illuminate the multidimensional

drivers of perceived customer service

quality and their relative importance.

Enhanced understanding of the aspectlevel determinants of service quality

assessments would offer practicing

healthcare managers greater instruction

on where and how resources should be

directed.

In addition, the question remains

whether customer satisfaction leads to

superior economic returns on investment. It is well established that satised customers represent the potential

for repeat service utilization and also

are a valuable source of referrals and

ideas for new business opportunities.

Moreover, retaining a current customer

is less costly than recruiting a new

one (Rust and Zahorik 1993). Thus,

strategies that succeed at retaining

customers should ultimately result in

higher prots (or surpluses) through

enhanced patronage combined with

reduced operating expenses. Further

research is needed to test the linkage

between patient satisfaction and nancial performance and to elaborate

the sequence paths that form any such

connection.

Notes

1. The employee survey asked workers about their overall satisfaction

with the VA, their appraisal of service

quality, and their perceptions about

121

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 121

1st proof

[121], (13)

Lines: 271 to 281

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[121], (13)

Journal of Healthcare Management 52:2 March/April 2007

various dimensions of work climate,

such as rewards/recognition, involvement, development, innovation, customer orientation, supervision, planning/measurement, respect/fairness,

diversity, information/communication,

conditions/resources, and teamwork.

2. The customer survey asked veterans to

evaluate various aspects pertaining to

the nature and quality of their service

experiences during recent visits to a VA

clinic, including waiting time, clinic

organization, communication, courtesy, involvement in decisions, continuity of care, and condence/trust

in providers, culminating in global

appraisals of quality and satisfaction.

3. Cronbachs alpha is a statistical index

that measures how well a set of items

measures a single unidimensional

underlying construct. Cronbachs alpha

ranges from 0 to 1.0, with 1.0 indicating the highest level of reliability or

condence one has in the measure being used. If the various items measuring a construct are highly correlated,

leading to an alpha approaching 1.0,

this is evidence that the measure is

reliable, because all of the items are

measuring the same construct.

References

Anderson, E. W., C. Fornell, and D. Lehmann.

1994. Customer Satisfaction, Market

Share, and Protability: Findings from

Sweden. Journal of Marketing 58 (3): 53

66.

Baker, T. L., and S. A. Taylor. 1997. Patient

Satisfaction and Service Quality Formation of Customers Future Purchase

Intentions in Competitive Health Service

Settings. Health Marketing Quarterly 15

(1): 115.

Batt, R. 2002. Managing Customer Services:

Human Resource Practices, Quit Rates,

and Sales Growth. Academy of Management Journal 45 (3): 58797.

Bigne, E., M. A. Moliner, and J. Sanchez.

2003. Perceived Quality and Satisfaction

in Multiservice Organizations: The Case

of Spanish Public Services. Journal of

Services Marketing 17 (4): 42042.

Bowen, D. E. and C. Ostroff. 2004. Understanding the HRM-Firm Performance

Linkages: The Role of the Strength of

the HRM System. Academy of Management

Review 29 (2): 20121.

Churchill, G. A., and C. Surprenant. 1982.

An Investigation Into the Determinants

of Customer Satisfaction. Journal of

Marketing Research 19 (4): 491504.

Cronin, J. J., and S. A. Taylor. 1992. Measuring Service Quality: A Reexamination and

Extension. Journal of Marketing 56 (3):

3355.

Crotts, J. C., D. R. Dickson, and R. C. Ford.

2005. Aligning Organizational Processes

with Mission: The Case of Service Excellence. Academy of Management Executive

19 (3): 5468.

Dean, A. M. 2004. Links Between Organizational and Customer Variables in Service

Delivery: Evidence, Contradictions, and

Challenges. International Journal of Service

Industry Management 15 (4): 33250.

George, W. R. 1990. Internal Marketing and

Organizational Behavior: A Partnership

in Developing Customer-Conscious Employees at Every Level. Journal of Business

Research 20 (1): 6370.

Gittell, J. H. 2002. Relationships Between

Service Providers and Their Impact on

Customers. Journal of Services Research 4

(4): 299311.

Goldstein, S. M. 2003. Employee Development: An Examination of Service Strategy

in a High-Contact Service Environment.

Production and Operations Management 12

(2): 186203

Hallowell, R. 1996. The Relationship of

Customer Satisfaction, Customer Loyalty,

and Protability: An Empirical Study.

International Journal of Service Industry

Management 7 (4): 2738.

Hallowell, R., L. A. Schlesinger, and J. Zornitsky. 1996. Internal Service Quality,

Customer and Job Satisfaction: Linkages

and Implications for Managers. Human

Resource Planning 19 (2): 2031.

Harmon, J., D. J. Scotti, S. Behson, G. Farius,

R. Petzel, J. Neuman, and L. Keashly.

2003. Effects of High-Involvement Work

Systems on Employee Satisfaction and

Services Costs in Veterans Healthcare.

122

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 122

1st proof

[122], (14)

Lines: 281 to 319

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[122], (14)

High-Performance Work Environment, Service Quality, and Customer Satisfaction

Journal of Healthcare Management 48 (6):

393405.

Hennig-Thurau, T. 2004. Customer Orientation of Service Employees: Its Impact

on Customer Satisfaction, Commitment,

Retention. International Journal of Service

Industry Management 15 (5): 46078.

Kelly, S. W. 1992. Developing customer

orientation among service employees.

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science

20 (1): 2736.

Lawler, E. E., S. A. Mohrman, and G. E. Ledford. 1995. Creating High Performance

Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Marley, K. A., D. A. Collier, and S. M. Goldstein. 2004. The role of clinical and

process quality in achieving patient satisfaction in hospitals. Decision Sciences 35

(3): 34969.

Nadler, D. A., and M. S. Gerstein. 1992. Designing High-Performance Work Systems:

Organizing People, Work, Technology

and Information. In Organizational Architecture, edited by D. A. Nadler, M. S.

Gerstein, R. B. Shaw and associates, 110

32. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nagy, M. S. 2002. Using a Single-Item Approach to Measure Facet Job Satisfaction.

Journal of Occupational and Organizational

Psychology 75 (1): 7786

Nelson, E. C., R. D. Hays, C. Larson, and P. B.

Batalden. 1989. The Patient Judgment

System: Reliability and Validity. Quality

Review Bulletin, 15 (6), 18491.

Newman, K., U. Maylor, and B. Chansarkar.

2001. The Nurse Retention, Quality of

Care and Patient Satisfaction Chain.

International Journal of Health Care Quality

Assurance 14 (2): 5768.

Pugh, S. D., J. Dietz, J. W. Wiley, and S. M.

Brooks. 2002. Driving Service Effectiveness Through Employee-Customer Linkages. Academy of Management Executive 16

(4): 7384.

Rainey, H. G., and Bozeman, B. 2000.Comparing Public and Private Organizations:

Empirical Research and the Power of the

A Priori. Journal of Public Administration

Research and Theory 10 (2): 44770.

Reichheld, F. F. 1996. The loyalty effect: the

hidden force behind growth, prots, and lasting value. Boston, MA: Harvard Business

School Press.

Rust, R. T., and R. L. Oliver. 1994. Service

Quality: Insights and Managerial Implications from the Frontier. In Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice,

edited by R. Rust and R. Oliver, 120.

Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rust, R. T., and A. Zahorik. 1993. Customer

Satisfaction, Customer Retention, and

Market Share. Journal of Retailing 69 (2):

193215.

Schneider, B., J. J. Parkington, and V. M.

Buxton. 1980. Employee and Customer

Perceptions of Service in Banks. Administrative Science Quarterly 25 (2): 25267.

Schneider, B., and D. E. Bowen. 1985. Employee and Customer Perceptions of Service in Banks: Replication and Extension.

Journal of Applied Psychology 70 (3): 423

33.

Schneider, B., and D. E. Bowen. 1993. The

Service Organization: Human Resources

Management is Crucial. Organizational

Dynamics 21 (4): 3952.

Schneider, B., S. S. White, and M. C. Paul.

1998. Linking Service Climate and

Customer Perceptions of Service Quality:

Test of a Causal Model. Journal of Applied

Psychology 83: (2) 15063.

Schumacker, R. E., and R. G. Lomax. 1996.

A Guide to Structural Equations Modeling.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Scotti, D. J., and R. N. Srinerock. 2003. Cognitive Predictors of Satisfaction with Hospital Inpatient Service Encounters Among

the Elderly: A Matter of Trust. Journal of

Hospital Marketing & Public Relations 14

(2): 322.

Storbacka, K., T. Strandvik, and C. Gronroos.

1994. Managing Customer Relationships

for Prot: The Dynamics of Relationship

Quality. International Journal of Service

Industry Management 5 (5): 2138.

Wanous, J. P., A. E. Reichers, and M. J. Hurdy.

1997. Overall Job Satisfaction: How

good are Single-Item Measures? Journal

of Applied Psychology 82 (2): 24752

Woo, H. C., W. Lee, C. Kim, S. Lee, and K. S.

Choi. 2004. The Impact of Visit Frequency on the Relationship Between Service Quality and Outpatient Satisfaction:

A South Korean Study. Health Services

Research 39 (1): 1334.

Yoon, M. H., S. E. Beatty, and J. Suh. 2001.

The Effect of Work Climate on Critical

123

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 123

1st proof

[123], (15)

Lines: 319 to 365

0.0pt PgVar

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[123], (15)

Journal of Healthcare Management 52:2 March/April 2007

Employee and Customer Outcomes: An

Journal of Service Industry Management 12

(5): 50021.

Employee-Level Analysis. International

P R A C T I T I O N E R

A P P L I C A T I O N

Daniel J. Messina, Ph.D., FACHE, LNHA, senior vice president and chief operating

ofcer, CentraState Healthcare System, Freehold, New Jersey

n this era of heightened market competition and consumerism, it is critical to

the success of healthcare organizations to understand the major drivers of patient

and employee perceptions of service quality. Creating a work climate that leads

to high levels of perceived service quality and patient satisfaction should be a

top priority for healthcare managers. But what is the correct path to follow? The

article by Scotti, Harmon, and Behson brings us one more step toward mapping

the course we should travel in this journey.

This article examines the effects of work environment on healthcare service

quality and customer satisfaction. The authors study the sequence of events

through which HPWS and customer orientation affect employee and customer

perceptions of service quality and their resulting effect on patient satisfaction in

113 VHA centers. Although the research ndings may be principally applicable to

VHA facilities, they provide lessons that apply and extend to the general healthcare

industry: There is a link between work environment and employee perceptions

of delivering high-quality customer service, and there is a link between employee

perceptions of customer service, customer perceptions of high-quality customer

service, and customer satisfaction.

In addition to the ndings that HPWS had a strong direct effect on employee

perception, one of the articles most interesting results related to the ripple effects

of HPWS and customer orientation. These factors are shown to exert a progressive

inuence, as their impact manifests itself through subsequent linkages in the chain

model. As demonstrated by the authors, a signicant portion of customer satisfaction can be explained through employee perceptions that managers at their respective organizations empower employees and thus develop a positive supportive

environment that provides the framework for exceptional high-quality customer

service.

The authors have raised our awareness of the interplay between the work environment and customer satisfaction. With limited existing research that has tested

the relationship between organizational work environment, service quality, and

customer satisfaction, the authors identify several opportunities for healthcare

executives to make practical use of the study ndings. They emphasize the necessity

of a complete and deep understanding of a high- performance work environment,

124

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 124

1st proof

[124], (16)

Lines: 365 to 391

0.93001pt PgV

Normal Page

PgEnds: TEX

[124], (16)

High-Performance Work Environment, Service Quality, and Customer Satisfaction

and the importance of hiring for attitude, making communication produce results,

and aligning performance for sustained customer service.

In summary, this research demonstrates the link between the workplace, service

quality, and customer satisfaction in the ambulatory care environment, an area of

focus that needs to be high on the radar screens of practicing healthcare executives.

[125], (17)

Lines: 391 to 395

529.53252pt PgVa

Normal Page

* PgEnds: PageBreak

[125], (17)

125

BookComp/ Health Administration Press/ Journal of Healthcare Management / Vol. 52, No. 2/ Page 125

1st proof

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Manual for Job-Communication Satisfaction-Importance (Jcsi) QuestionnaireD'EverandManual for Job-Communication Satisfaction-Importance (Jcsi) QuestionnairePas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of High Performance Work Systems in The Health-Care Industry, Employee Reactions, Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer LoyaltyDocument21 pagesThe Impact of High Performance Work Systems in The Health-Care Industry, Employee Reactions, Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer LoyaltyHandsome RobPas encore d'évaluation

- Bobi Review TaiwanDocument5 pagesBobi Review Taiwanandualem mengistuPas encore d'évaluation

- High Performance HR Practices and Customer Satisfaction: Employee Process MechanismsDocument27 pagesHigh Performance HR Practices and Customer Satisfaction: Employee Process MechanismsAndre AxelbandPas encore d'évaluation

- 2009 ImprovingworkenvironmentsDocument11 pages2009 ImprovingworkenvironmentsMarta GonçalvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Performance Appraisal and Work Motivation On Work Performance Ofemployee: With Special Reference To A MultiSpecialtyHospital in KeralaDocument4 pagesImpact of Performance Appraisal and Work Motivation On Work Performance Ofemployee: With Special Reference To A MultiSpecialtyHospital in KeralaIOSRjournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Job Satisfaction and ManagementDocument21 pagesJob Satisfaction and ManagementTxkti BabelPas encore d'évaluation

- Megha Mrp1Document21 pagesMegha Mrp1TheRanjith18Pas encore d'évaluation

- Danford Et Al-2008-New Technology, Work and EmploymentDocument16 pagesDanford Et Al-2008-New Technology, Work and EmploymentThyya ChemmuetPas encore d'évaluation

- 08-06-2021-1623140416-6-Impact - Ijrbm-1. Ijrbm - "HR Retention Practices in Hospitals" - Validating The Measurement ScaleDocument8 pages08-06-2021-1623140416-6-Impact - Ijrbm-1. Ijrbm - "HR Retention Practices in Hospitals" - Validating The Measurement ScaleImpact JournalsPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategies For Improving Individual Performance and Job Satisfaction at Meadowvale HealthDocument8 pagesStrategies For Improving Individual Performance and Job Satisfaction at Meadowvale HealthcintoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Workforce Performance v1Document9 pagesWorkforce Performance v1Ousman BahPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal PernapasanDocument13 pagesJurnal PernapasanFance RonaldoPas encore d'évaluation

- Essay On The Management TheoryDocument12 pagesEssay On The Management Theorycmn88100% (1)

- Customer Experience Quality in Health Care SSRN-id3540060Document5 pagesCustomer Experience Quality in Health Care SSRN-id3540060Sherly ThendianPas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring The Impact of Resilience, Self-Efficacy, Optimism and Organizational Resources On Work Engagement.Document11 pagesExploring The Impact of Resilience, Self-Efficacy, Optimism and Organizational Resources On Work Engagement.Charmaine ShaninaPas encore d'évaluation

- Healthcare Quality Innovation and Performance Throug - 2016 - Technological ForeDocument10 pagesHealthcare Quality Innovation and Performance Throug - 2016 - Technological ForeAngela MarinPas encore d'évaluation

- High Performance Work Practices: Penny TamkinDocument20 pagesHigh Performance Work Practices: Penny TamkinsadakaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Care Professional Perception Towards Engagement Factors With Reference To Multispecialty Hospital in ChennaiDocument11 pagesHealth Care Professional Perception Towards Engagement Factors With Reference To Multispecialty Hospital in Chennaiindex PubPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effects of Employee Satisfaction Org PDFDocument14 pagesThe Effects of Employee Satisfaction Org PDFThanh TâmPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Employee EngagementDocument15 pagesIntroduction To Employee EngagementKhaterehAZPas encore d'évaluation

- HRMT20024 - Assessment 2 - 1Document16 pagesHRMT20024 - Assessment 2 - 1bitetPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On Employee Health and SafetyDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Employee Health and SafetyafmztvjdbizbamPas encore d'évaluation

- HRM Employee RetentionDocument14 pagesHRM Employee RetentionKalbe HaiderPas encore d'évaluation

- Woznyj Climate and Organizational Performance in Long-Term Care Facilities - The Role of Affective CommitmentDocument23 pagesWoznyj Climate and Organizational Performance in Long-Term Care Facilities - The Role of Affective CommitmentzooopsPas encore d'évaluation

- GROUP 3 CHAPTER 1 FinalDocument22 pagesGROUP 3 CHAPTER 1 FinalStella Therese BeronioPas encore d'évaluation

- Employees' Responses To High Performance Work Systems: Assessing HPWS EffectivenessDocument12 pagesEmployees' Responses To High Performance Work Systems: Assessing HPWS EffectivenessNikhil AlvaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Development of The Job Satisfaction Scale For Hospital Staff in TaiwanDocument14 pagesThe Development of The Job Satisfaction Scale For Hospital Staff in Taiwanz.kazemzadeh79Pas encore d'évaluation

- Influence of Reward Systems On Employee Retention in Faith Based Health Organizations in Kenya A Case of Mukumu Hospital, KenyaDocument10 pagesInfluence of Reward Systems On Employee Retention in Faith Based Health Organizations in Kenya A Case of Mukumu Hospital, KenyaMARKPas encore d'évaluation

- Management Commitment To Service Quality and Service Recovery Performance: A Study of Frontline Employees in Public and Private HospitalsDocument21 pagesManagement Commitment To Service Quality and Service Recovery Performance: A Study of Frontline Employees in Public and Private HospitalsMentariPas encore d'évaluation

- Improving The Health Care Work Environment: Implications For Research, Practice, and PolicyDocument4 pagesImproving The Health Care Work Environment: Implications For Research, Practice, and PolicyMarta GonçalvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Deta Potta SetaaDocument30 pagesDeta Potta SetaaVaibhav KaushikPas encore d'évaluation

- Synopsis by Komal Mishra 22GSOB2010267Document9 pagesSynopsis by Komal Mishra 22GSOB2010267Mayank YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Jawahar (200-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesJawahar (200-WPS OfficeJyotika PatyalPas encore d'évaluation

- Zhang 2011Document19 pagesZhang 2011M'ir Usai'lPas encore d'évaluation

- Review Report HRMDocument2 pagesReview Report HRMAbizwagPas encore d'évaluation

- An Empirical Study of Employee Loyalty, Service Quality and Firm Performance in The Service IndustryDocument12 pagesAn Empirical Study of Employee Loyalty, Service Quality and Firm Performance in The Service IndustryKazim NaqviPas encore d'évaluation

- High Performance Management Research ProposalDocument6 pagesHigh Performance Management Research ProposalNazish Sohail100% (1)

- Attracting and Retaining Staff in HealthcareDocument11 pagesAttracting and Retaining Staff in HealthcareAnonymous MFh19TBPas encore d'évaluation

- 12.gittell, Jody Hoffer, and Rob Seidner. Human Resource Management in The Service SectorDocument13 pages12.gittell, Jody Hoffer, and Rob Seidner. Human Resource Management in The Service SectormiudorinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring The Impact of High Performance Work Systems in Professional Service Firms: A Practices-Resources-Uses-Performance ApproachDocument18 pagesExploring The Impact of High Performance Work Systems in Professional Service Firms: A Practices-Resources-Uses-Performance ApproachshivanithapliyalPas encore d'évaluation

- KAS 270 ProptyutosalDocument15 pagesKAS 270 ProptyutosalzulfifarrukhPas encore d'évaluation

- The Mediating Effectof Patient Satisfactioninthe PatientsDocument26 pagesThe Mediating Effectof Patient Satisfactioninthe Patientsbe a doctor for you Medical studentPas encore d'évaluation

- 421 FullDocument9 pages421 Fullprabu06051984Pas encore d'évaluation

- Employee Engagement and Its Relation To Hospital Performance in A Tertiary Care Teaching HospitalDocument9 pagesEmployee Engagement and Its Relation To Hospital Performance in A Tertiary Care Teaching Hospitalkanthi056Pas encore d'évaluation

- Improving Hospital Performance and Productivity With The Balanced Scorecard - 2Document22 pagesImproving Hospital Performance and Productivity With The Balanced Scorecard - 2Yunita Soraya HusinPas encore d'évaluation

- Total Quality ImprovementDocument21 pagesTotal Quality ImprovementMar DiyanPas encore d'évaluation

- An Examination of The Role of Perceived Support and Employee Commitment in Employee-Customer EncountersDocument11 pagesAn Examination of The Role of Perceived Support and Employee Commitment in Employee-Customer EncountersLeornard MukuruPas encore d'évaluation

- Take Home ExamsDocument4 pagesTake Home Examshcny46wsjjPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study On Quality of Work Life: Key Elements & It's ImplicationsDocument4 pagesA Study On Quality of Work Life: Key Elements & It's ImplicationsAbirami DjPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter One and Two WelfareDocument18 pagesChapter One and Two WelfareAjani AbeeblahiPas encore d'évaluation

- Performance Appraisal Systems in The Hospital Sector - A Research Based On Hospitals in KeralaDocument10 pagesPerformance Appraisal Systems in The Hospital Sector - A Research Based On Hospitals in KeralaTJPRC PublicationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Driving Employee Engagement in Nationalized Banks in India: AbstractDocument4 pagesDriving Employee Engagement in Nationalized Banks in India: AbstractCma Pushparaj KulkarniPas encore d'évaluation

- EmployeeRelations AproorvapaperDocument18 pagesEmployeeRelations AproorvapaperGemmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Iwb 1Document15 pagesIwb 1Niaz Bin MiskeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Relationship Between Rewards and Employee's Performance in The Cement Industry in PakistanDocument11 pagesRelationship Between Rewards and Employee's Performance in The Cement Industry in PakistanMuhammad Haider AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Article Review Siti Suraya - 2020476914Document9 pagesArticle Review Siti Suraya - 2020476914Siti SurayaPas encore d'évaluation

- MS 8 - 2 - RamlallDocument10 pagesMS 8 - 2 - RamlallLakshmi Kanth RajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature ReviewDocument2 pagesLiterature Reviewniea lomlPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Employee Empowerment On Employee Satisfaction and Service Quality: Empirical Evidence From Financial Enterprizes in BangladeshDocument12 pagesThe Impact of Employee Empowerment On Employee Satisfaction and Service Quality: Empirical Evidence From Financial Enterprizes in BangladeshJoel D'vasiaPas encore d'évaluation

- HypertensionDocument39 pagesHypertensionFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Al Lib 24.2012725923351516 PDFDocument2 pagesAl Lib 24.2012725923351516 PDFFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- HT Dental PatientDocument13 pagesHT Dental PatientFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Smart Dentin Replacement: MarketplaceDocument2 pagesSmart Dentin Replacement: MarketplaceFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- GuidelineDocument3 pagesGuidelineFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Teeth BleachingDocument65 pagesTeeth BleachingFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Hospitals MethodologyDocument125 pagesBest Hospitals MethodologyAngeline YeoPas encore d'évaluation

- 1145Document8 pages1145Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Hypertension Profile in An Adult Dental PopulationDocument7 pagesHypertension Profile in An Adult Dental PopulationFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Change of Address For Jada Manuscript Submission, Review: N E W SDocument4 pagesChange of Address For Jada Manuscript Submission, Review: N E W SFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- 488 ADocument8 pages488 AFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- The Perceived GronroosDocument3 pagesThe Perceived GronrooskyveligPas encore d'évaluation

- The Following Resources Related To This Article Are Available Online atDocument8 pagesThe Following Resources Related To This Article Are Available Online atFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Dental Research: Regional Anesthesia in Dental and Oral Surgery: A Plea For Its StandardizationDocument15 pagesJournal of Dental Research: Regional Anesthesia in Dental and Oral Surgery: A Plea For Its StandardizationFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Skin Colour Is Associated With Periodontal Disease in Brazilian Adults: A Population-Based Oral Health SurveyDocument6 pagesSkin Colour Is Associated With Periodontal Disease in Brazilian Adults: A Population-Based Oral Health SurveyFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Rational Approach To Management of Febrile Seizures: CommentaryDocument2 pagesRational Approach To Management of Febrile Seizures: CommentaryFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Convulsion Febril - Febrile Seizures Risks, Evaluation, and Prognosis - Am Fam Physician. 2012Document5 pagesConvulsion Febril - Febrile Seizures Risks, Evaluation, and Prognosis - Am Fam Physician. 2012Nataly Zuluaga VilladaPas encore d'évaluation

- Product Pricelist: SINGLE ESSENTIAL OIL (Original 15ml or 5 ML)Document9 pagesProduct Pricelist: SINGLE ESSENTIAL OIL (Original 15ml or 5 ML)Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007 Vestergaard 911 8Document8 pagesAm. J. Epidemiol. 2007 Vestergaard 911 8Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- BMJ 334 7588 CR 00307Document5 pagesBMJ 334 7588 CR 00307Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- 6807 Kab Tabalong Nilai TKD Final (Panselnas)Document71 pages6807 Kab Tabalong Nilai TKD Final (Panselnas)Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Narver & Slater - The Effect of A Market Orientation On Business ProfitabilityDocument17 pagesNarver & Slater - The Effect of A Market Orientation On Business ProfitabilityCyoko DaynizPas encore d'évaluation

- Non Hodgkin LymphomaDocument35 pagesNon Hodgkin LymphomaFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Febrile Seizures in Children: ReviewDocument12 pagesAssessment of Febrile Seizures in Children: ReviewFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Transformation: Programme 2007-2010Document20 pagesTransformation: Programme 2007-2010Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- A Corporate Character Scale To Assess Views On Org. ReputationDocument24 pagesA Corporate Character Scale To Assess Views On Org. ReputationJohn SucksterPas encore d'évaluation

- A Corporate Character Scale To Assess Views On Org. ReputationDocument24 pagesA Corporate Character Scale To Assess Views On Org. ReputationJohn SucksterPas encore d'évaluation

- 6311124Document11 pages6311124Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- 11924953Document20 pages11924953Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Man Bni PNT XXX 105 Z015 I17 Dok 886160 03 000Document36 pagesMan Bni PNT XXX 105 Z015 I17 Dok 886160 03 000Eozz JaorPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethernet/Ip Parallel Redundancy Protocol: Application TechniqueDocument50 pagesEthernet/Ip Parallel Redundancy Protocol: Application Techniquegnazareth_Pas encore d'évaluation

- Intelligent Status Monitoring System For Port Machinery: RMGC/RTGCDocument2 pagesIntelligent Status Monitoring System For Port Machinery: RMGC/RTGCfatsahPas encore d'évaluation

- Third Party Risk Management Solution - WebDocument16 pagesThird Party Risk Management Solution - Webpreenk8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurial Capacity Building: A Study of Small and Medium Family-Owned Enterprisesin PakistanDocument3 pagesEntrepreneurial Capacity Building: A Study of Small and Medium Family-Owned Enterprisesin PakistanMamoonaMeralAysunPas encore d'évaluation

- MPI Unit 4Document155 pagesMPI Unit 4Dishant RathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Governance Operating Model: Structure Oversight Responsibilities Talent and Culture Infrastructu REDocument6 pagesGovernance Operating Model: Structure Oversight Responsibilities Talent and Culture Infrastructu REBob SolísPas encore d'évaluation

- Hitachi Vehicle CardDocument44 pagesHitachi Vehicle CardKieran RyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Homework 9Document1 pageHomework 9Nat Dabuét0% (1)

- Inverter 2 chiềuDocument2 pagesInverter 2 chiềuKhánh Nguyễn MinhPas encore d'évaluation

- Bridge Over BrahmaputraDocument38 pagesBridge Over BrahmaputraRahul DevPas encore d'évaluation

- Ultra Electronics Gunfire LocatorDocument10 pagesUltra Electronics Gunfire LocatorPredatorBDU.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Rights Vocabulary Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesCivil Rights Vocabulary Lesson PlanKati ArmstrongPas encore d'évaluation

- Javascript Notes For ProfessionalsDocument490 pagesJavascript Notes For ProfessionalsDragos Stefan NeaguPas encore d'évaluation

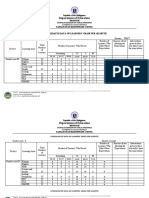

- Department of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterUsagi HamadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Management PriniciplesDocument87 pagesManagement Priniciplesbusyboy_spPas encore d'évaluation

- Probation Period ReportDocument17 pagesProbation Period ReportMiranti Puspitasari0% (1)

- Core CompetenciesDocument3 pagesCore Competenciesapi-521620733Pas encore d'évaluation

- File RecordsDocument161 pagesFile RecordsAtharva Thite100% (2)

- Audi A4-7Document532 pagesAudi A4-7Anonymous QRVqOsa5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Blackberry: Terms of Use Find Out MoreDocument21 pagesBlackberry: Terms of Use Find Out MoreSonu SarswatPas encore d'évaluation

- Table of Reinforcement Anchorage Length & Lap Length - Eurocode 2Document7 pagesTable of Reinforcement Anchorage Length & Lap Length - Eurocode 2NgJackyPas encore d'évaluation

- Waves and Ocean Structures Journal of Marine Science and EngineeringDocument292 pagesWaves and Ocean Structures Journal of Marine Science and Engineeringheinz billPas encore d'évaluation

- Waste Biorefinery Models Towards Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Critical Review and Future Perspectives2016bioresource Technology PDFDocument11 pagesWaste Biorefinery Models Towards Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Critical Review and Future Perspectives2016bioresource Technology PDFdatinov100% (1)

- str-w6754 Ds enDocument8 pagesstr-w6754 Ds enAdah BumbonPas encore d'évaluation

- Hofstede's Cultural DimensionsDocument35 pagesHofstede's Cultural DimensionsAALIYA NASHATPas encore d'évaluation

- Sim Uge1Document62 pagesSim Uge1ALLIAH NICHOLE SEPADAPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Construction HandbookDocument498 pagesModern Construction HandbookRui Sousa100% (3)

- Supply List & Resource Sheet: Granulation Techniques DemystifiedDocument6 pagesSupply List & Resource Sheet: Granulation Techniques DemystifiedknhartPas encore d'évaluation

- Leveriza Heights SubdivisionDocument4 pagesLeveriza Heights SubdivisionTabordan AlmaePas encore d'évaluation