Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Rational Approach To Management of Febrile Seizures: Commentary

Transféré par

Ferdina NidyasariTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Rational Approach To Management of Febrile Seizures: Commentary

Transféré par

Ferdina NidyasariDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Indian J Pediatr (February 2013) 80(2):149150

DOI 10.1007/s12098-012-0843-4

COMMENTARY

Rational Approach to Management of Febrile Seizures

Siba Prosad Paul & Ravindranath Chinthapalli

Received: 23 March 2012 / Accepted: 20 June 2012 / Published online: 6 July 2012

# Dr. K C Chaudhuri Foundation 2012

Febrile seizure (FS) is an event (i.e., seizure) in children

aged between 6 mo and 6 y associated with a fever, but

without evidence of any intracranial infection or metabolic

disturbance [13]. FS has been described centuries ago as is

evident from the work of Thomas Willis (1684) entitled Of

Convulsive Diseases [4]. The peak age for onset of FS is

18 mo; it occurs in 2 to 5% of children but more frequently

in the Asian race [3]. FS occurs in up to 10% of children of

Indian origin [5].

The exact cause of FS remains unknown. It is considered

to be multi-factorial; both genetic and environmental factors

are thought to contribute to its pathogenesis. The inheritance

is likely to be polygenic. There are a small number of

families where an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance has been identified and is referred to as febrile seizure

susceptibility trait. The molecular mechanism of FS needs

further understanding; however, the underlying mutations

have been found in genes encoding the sodium channel and

the gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors. These receptors

have also been associated with another epilepsy syndrome

seen in early infancy viz., Severe Myoclonic Epilepsy of

Infancy which initially presents with prolonged fever and

subsequent seizures are precipitated by fever [5].

A child presenting with FS needs emergency stabilization

with ABC (airway, breathing, circulation) approach. It is

important to check blood glucose after the first FS [2, 6].

Further management decisions will depend on the type:

simple or complex FS [6]. Complex FS usually lasts

15 min and are characterized by multiple episodes of

seizures during the same illness, focal seizures, not

S. P. Paul (*) : R. Chinthapalli

Department of Pediatrics, Great Western Hospital,

Marlborough Road,

Swindon SN3 6BB, UK

e-mail: siba@doctors.org.uk

regaining full consciousness within 1 h and may have features of Todds paresis [2, 6].

In a fully immunized child with simple FS, investigations

such as blood tests, lumbar puncture and neuroimaging or

EEG may not be necessary [2, 6]. The first episode of FS,

especially in children <1 y of age requires a cautious

approach and it needs to be differentiated from acute symptomatic seizures due to risk of CNS infection [4]. Children

with focal FS should be considered for non-urgent MRI scan

and EEG as this may be the first sign of an epilepsy disorder.

Once a diagnosis of FS is established in a child, a further

episode of FS does not need repeat investigations.

Children with simple FS have excellent prognosis. Onethird of children with FS will have further episodes of FS

during subsequent illnesses. The risk factors for recurrence

of FS include first episode at <18 mo of age, lower body

temperature (38C) during seizure, shorter duration of

fever (<1 h) before the onset of FS and a strong family

history for FS [6].

The parents and to a certain extent the health professionals can understandably be anxious to prevent another episode of FS [2, 6]. This may necessitate the consideration for

prophylactic therapies. Vast majority of children do not need

or benefit from prophylactic anticonvulsants and is rarely

used in the UK practice [5].

The decision to initiate any prophylactic therapy should

be discussed in details with the parents and any benefit

should be weighed against the potential risk. Following

circumstances may need consideration for prophylactic anticonvulsant therapies [2, 4, 7]:

&

&

&

Frequent FS over short period of time (3 FS in 6 mo)

FS lasting >15 min or required anticonvulsant therapy to

stop the seizure

Child living in an area geographically isolated from

immediate medical access

150

Intermittent therapy during FS episodes with benzodiazepines such as rectal diazepam, clobazam or buccal midazolam has been found to be effective in arresting an

episode of FS [2, 4, 8]. However, buccal midazolam has

less sedative effect and causes less respiratory depression

but has similar efficacy. It is better accepted socially in the

community [8]. Oral phenobarbitone during febrile episodes

has not been found to be effective in arresting an episode of

FS [4].

Antipyretic therapy has not been found to be effective in

preventing FS [1, 36]. Parents need to be explained that

giving antipyretics either acutely or regularly during a

febrile episode does not reduce the risk for recurrence of

FS; the only rationale for its use is to make the child more

comfortable [1, 4]. Vigorous attempts to reduce fever, therefore, should not be recommended by the physicians.

Long term prophylaxis for FS with anticonvulsant therapy

is best being avoided. However, children with febrile status

epilepticus, complex or recurrent FS (>6 episodes of FS/year

in spite of use of intermittent abortive therapy) may be

considered for long term anticonvulsant therapy [2].

The two useful drugs are sodium valproate and phenobarbitone [24, 6]. Studies have shown that sodium valproate is better in controlling further FS and the side

effects are found to be less when compared to phenobarbitone; therefore, it may be preferred where long term therapy

is considered [4, 9, 10]. The duration of anticonvulsant

therapy remains controversial. Some authorities suggest that

it should be continued for 2 y after the last episode of FS

while others feel it should be continued till child is 6 y of

age when they are likely to grow out of this condition [11].

Close monitoring is necessary for children on long

term prophylactic anticonvulsant therapy and parents

should be made aware of the potential side effects. These

may include behavioral and subtle cognitive difficulties,

increase in appetite and problems with hepatic, hemopoetic and bone marrow changes.

FS are common in the pediatric practice with an excellent

prognosis. The role of prophylactic anticonvulsant therapy

should be carefully judged for each child. The intended

benefits and potential side effects should be weighed and

Indian J Pediatr (February 2013) 80(2):149150

clearly explained to the parents. Regular use of antipyretics

during a febrile episode does not prevent FS. Long term

anticonvulsant therapy may occasionally be necessary in a

few children with FS.

Conflict of Interest None.

Role of Funding Source

None.

References

1. Strengell T, Uhari M, Tarkka R, et al. Antipyretic agents for

preventing recurrences of febrile seizures: randomized controlled

trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:799804.

2. Expert Committee on Pediatric Epilepsy, Indian Academy of

Pediatrics. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of childhood

epilepsy. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:68198.

3. Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management,

Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures American Academy of

Pediatrics. Febrile seizures: clinical practice guideline for the

long-term management of the child with simple febrile seizures.

Pediatrics. 2008;121:12816.

4. Lux AL. Treatment of febrile seizures: historical perspective,

current opinions, and potential future directions. Brain Dev.

2010;32:4250.

5. Mewasingh LD. Febrile seizures. Clin Evid (Online). 2008;2008:0324.

6. Oluwabusi T, Sood SK. Update on the management of simple

febrile seizures: emphasis on minimal intervention. Curr Opin

Pediatr. 2012;24:25965.

7. Capovilla G, Mastrangelo M, Romeo A, Vigevano F. Recommendations for the management of febrile seizures: Ad Hoc Task

Force of LICE Guidelines Commission. Epilepsia. 2009;50:26.

8. Scott RC, Besag FMC, Neville BGR. Buccal midazolam and rectal

diazepam for treatment of prolonged seizures in childhood and

adolescence: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:6236.

9. Mamelle N, Mamelle JC, Plasse JC, Revol M, Gilly R. Prevention

of recurrent febrile convulsionsa randomized therapeutic assay:

sodium valproate, phenobarbital and placebo. Neuropediatrics.

1984;15:3742.

10. Wallace SJ, Smith JA. Successful prophylaxis against febrile

convulsions with valproic acid or phenobarbitone. Br Med J.

1980;280:3534.

11. Camfield P, Camfield C. When is it safe to discontinue AED

treatment? Epilepsia. 2008;49:258.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Current Management of Febrile Seizures in Japan: An OverviewDocument7 pagesCurrent Management of Febrile Seizures in Japan: An OverviewEka Loebiz D'kemponPas encore d'évaluation

- Risk Factors of Recurrence of Febrile Seizures in Children in A Tertiary Care Hospital in Kanpur - A One Year Follow Up StudyDocument7 pagesRisk Factors of Recurrence of Febrile Seizures in Children in A Tertiary Care Hospital in Kanpur - A One Year Follow Up StudyFarra PattipawaePas encore d'évaluation

- Febrile Seizures: Clinical Practice Guideline For The Long-Term Management of The Child With Simple Febrile SeizuresDocument8 pagesFebrile Seizures: Clinical Practice Guideline For The Long-Term Management of The Child With Simple Febrile SeizuresRichel Edwin Theofili PattikawaPas encore d'évaluation

- Formation of Neuronal Excitability and Parental Reactions to Febrile SeizuresDocument4 pagesFormation of Neuronal Excitability and Parental Reactions to Febrile SeizuresejkohPas encore d'évaluation

- Simple Versus Complex Febrile SeizureDocument18 pagesSimple Versus Complex Febrile SeizurePiet SeLoesindPas encore d'évaluation

- BFCDocument7 pagesBFCKalvinKonOjalesStrangerPas encore d'évaluation

- NewbornEmergenices2006 PDFDocument16 pagesNewbornEmergenices2006 PDFRana SalemPas encore d'évaluation

- Febrile Seizures: Clinical Practice Guideline For The Long-Term Management of The Child With Simple Febrile SeizuresDocument11 pagesFebrile Seizures: Clinical Practice Guideline For The Long-Term Management of The Child With Simple Febrile SeizuresWiltar NaibahoPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Febrile SeizuresDocument9 pagesManagement of Febrile SeizuresLi FaungPas encore d'évaluation

- Intermittent Oral Levetiracetam Reduces Febrile Seizure RecurrenceDocument9 pagesIntermittent Oral Levetiracetam Reduces Febrile Seizure RecurrenceKoas PatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Journjkljal 2 PDFDocument9 pagesJournjkljal 2 PDFAan AchmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentasi Jurnal Kejang DemamDocument21 pagesPresentasi Jurnal Kejang DemamSeptiana WahyuPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Febrile Seizures in Children: Khawaja Tahir Mahmood, Tooba Fareed, Rabia TabbasumDocument5 pagesManagement of Febrile Seizures in Children: Khawaja Tahir Mahmood, Tooba Fareed, Rabia TabbasumrizkianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Epilepsy: EssentialsDocument3 pagesEpilepsy: Essentialshannah_pharmPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency Delirium in PediatricDocument15 pagesEmergency Delirium in PediatricUzZySusFabregasPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and ResidentsDocument6 pagesCase Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and Residentssantosaerwin6591100% (1)

- Waiting Time EpilepsyDocument7 pagesWaiting Time EpilepsyFlavia Angelina SatopohPas encore d'évaluation

- 100 Case Studies in Pathophysiology-532hlm (Warna Hanya Cover)Document11 pages100 Case Studies in Pathophysiology-532hlm (Warna Hanya Cover)Haymanot AnimutPas encore d'évaluation

- Treating The Wheezing Infant: Ronina A. Covar, MD, Joseph D. Spahn, MDDocument24 pagesTreating The Wheezing Infant: Ronina A. Covar, MD, Joseph D. Spahn, MDSophia RosePas encore d'évaluation

- USMLE Step 3 Lecture Notes 2021-2022: Internal Medicine, Psychiatry, EthicsD'EverandUSMLE Step 3 Lecture Notes 2021-2022: Internal Medicine, Psychiatry, EthicsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (9)

- Clinical Management Review 2023-2024: Volume 1: USMLE Step 3 and COMLEX-USA Level 3D'EverandClinical Management Review 2023-2024: Volume 1: USMLE Step 3 and COMLEX-USA Level 3Évaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Technical Report: Treatment of The Child With Simple Febrile SeizuresDocument59 pagesTechnical Report: Treatment of The Child With Simple Febrile SeizuresCiara May SeringPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughD'EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughSang Heon ChoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Treatment of Migraine Headaches in Children and AdolescentsDocument11 pagesThe Treatment of Migraine Headaches in Children and Adolescentsdo leePas encore d'évaluation

- Laporan Kasus Tonsilofaringitis AkutDocument8 pagesLaporan Kasus Tonsilofaringitis AkutAvhindAvhindPas encore d'évaluation

- EB June1Document7 pagesEB June1amiruddin_smartPas encore d'évaluation

- Complex Febrile Seizures - Dr. Albert JamesDocument4 pagesComplex Febrile Seizures - Dr. Albert JamesRohit BharadwajPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of The Effects of Clobazam and Diazepam in Prevention of Recurrent Febrile Seizures PDFDocument5 pagesComparison of The Effects of Clobazam and Diazepam in Prevention of Recurrent Febrile Seizures PDFCharina Geofhany DeboraPas encore d'évaluation

- Febrile Seizures: Jithangi WanigasingheDocument5 pagesFebrile Seizures: Jithangi WanigasingheNadya ErlianiePas encore d'évaluation

- Pre-hospital Management of Febrile Seizures in ChildrenDocument5 pagesPre-hospital Management of Febrile Seizures in Childrenchaz5727xPas encore d'évaluation

- Screening For Good Health: The Australian Guide To Health Screening And ImmunisationD'EverandScreening For Good Health: The Australian Guide To Health Screening And ImmunisationPas encore d'évaluation

- Guideline Summary NGC-9469: RecommendationsDocument6 pagesGuideline Summary NGC-9469: RecommendationsIbrahim MachmudPas encore d'évaluation

- Febrile SeizureDocument8 pagesFebrile Seizureanon_944507650Pas encore d'évaluation

- Working with Children Who Need Long-term Respiratory SupportD'EverandWorking with Children Who Need Long-term Respiratory SupportPas encore d'évaluation

- Febrile Seizures: Definition and ClassificationDocument3 pagesFebrile Seizures: Definition and ClassificationArmin AbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Febrile Convulsion in ChildrenDocument8 pagesManagement of Febrile Convulsion in ChildrenCarlos LeonPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Evidence ConciseDocument4 pagesClinical Evidence ConciseisxyPas encore d'évaluation

- Glauser2016 PDFDocument14 pagesGlauser2016 PDFDiana De La CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide to Health Maintenance and Disease Prevention: What You Need to Know. Why You Should Ask Your DoctorD'EverandGuide to Health Maintenance and Disease Prevention: What You Need to Know. Why You Should Ask Your DoctorPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric Seizure and Status Epilepticus GuideDocument8 pagesPediatric Seizure and Status Epilepticus Guidestrawberry piePas encore d'évaluation

- Cerebral PalsyDocument10 pagesCerebral PalsyGeorgina HughesPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Status Epilepticus in Children: Clinical MedicineDocument19 pagesManagement of Status Epilepticus in Children: Clinical MedicineDienda AleashaPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Patent Ductus Arteriosus: MAMC, New Delhi, IndiaDocument1 pageManagement of Patent Ductus Arteriosus: MAMC, New Delhi, IndiadrtgodePas encore d'évaluation

- FINAL Current Guidelines For The Management of Asthma in Young ChildrenDocument45 pagesFINAL Current Guidelines For The Management of Asthma in Young ChildrenivanPas encore d'évaluation

- Approach To Refractory Childhood SeizuresDocument10 pagesApproach To Refractory Childhood SeizureskholisahnasutionPas encore d'évaluation

- Iron Deficiency and Febrile SeizuresDocument5 pagesIron Deficiency and Febrile SeizureschristiePas encore d'évaluation

- English in Paediatrics 2: Textbook for Mothers, Babysitters, Nurses, and PaediatriciansD'EverandEnglish in Paediatrics 2: Textbook for Mothers, Babysitters, Nurses, and PaediatriciansPas encore d'évaluation

- One Body-One Life: Health Screening Disease Prevention Personal Health Record Leading Causes of DeathD'EverandOne Body-One Life: Health Screening Disease Prevention Personal Health Record Leading Causes of DeathPas encore d'évaluation

- Ref 1Document7 pagesRef 1Tiago BaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Studyprotocol Open Access: Dalziel Et Al. BMC Pediatrics (2017) 17:152 DOI 10.1186/s12887-017-0887-8Document9 pagesStudyprotocol Open Access: Dalziel Et Al. BMC Pediatrics (2017) 17:152 DOI 10.1186/s12887-017-0887-8navali rahmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Migra inDocument6 pagesMigra inIka IrawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Febrile SeizureDocument6 pagesFebrile SeizurepipimseptianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal AsmaDocument11 pagesJurnal AsmaAi Siti Rika FauziahPas encore d'évaluation

- Shelf Prep: Pediatric Patient NotesDocument9 pagesShelf Prep: Pediatric Patient NotesMaría Camila Pareja ZabalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Article: ObjectiveDocument5 pagesResearch Article: ObjectiveFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Manejo Estatus 2020Document14 pagesManejo Estatus 2020Juanda MedinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Pediatric Febrile SeizuresDocument2 pagesManagement of Pediatric Febrile SeizuresShewit MisginaPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice GuidelineDocument3 pagesPractice Guidelineclarajimena25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wheezing in Children Approaches To Diagnosis and MDocument6 pagesWheezing in Children Approaches To Diagnosis and MMemory LastPas encore d'évaluation

- Al Lib 24.2012725923351516 PDFDocument2 pagesAl Lib 24.2012725923351516 PDFFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Teeth BleachingDocument65 pagesTeeth BleachingFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- The Following Resources Related To This Article Are Available Online atDocument8 pagesThe Following Resources Related To This Article Are Available Online atFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Change of Address For Jada Manuscript Submission, Review: N E W SDocument4 pagesChange of Address For Jada Manuscript Submission, Review: N E W SFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- HT Dental PatientDocument13 pagesHT Dental PatientFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Dental Research: Regional Anesthesia in Dental and Oral Surgery: A Plea For Its StandardizationDocument15 pagesJournal of Dental Research: Regional Anesthesia in Dental and Oral Surgery: A Plea For Its StandardizationFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- HypertensionDocument39 pagesHypertensionFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Smart Dentin Replacement: MarketplaceDocument2 pagesSmart Dentin Replacement: MarketplaceFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- GuidelineDocument3 pagesGuidelineFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Hypertension Profile in An Adult Dental PopulationDocument7 pagesHypertension Profile in An Adult Dental PopulationFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- 488 ADocument8 pages488 AFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- 1145Document8 pages1145Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Convulsion Febril - Febrile Seizures Risks, Evaluation, and Prognosis - Am Fam Physician. 2012Document5 pagesConvulsion Febril - Febrile Seizures Risks, Evaluation, and Prognosis - Am Fam Physician. 2012Nataly Zuluaga VilladaPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Hospitals MethodologyDocument125 pagesBest Hospitals MethodologyAngeline YeoPas encore d'évaluation

- Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007 Vestergaard 911 8Document8 pagesAm. J. Epidemiol. 2007 Vestergaard 911 8Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- BMJ 334 7588 CR 00307Document5 pagesBMJ 334 7588 CR 00307Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Essential Oil Price ListDocument9 pagesEssential Oil Price ListFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Febrile Seizures in Children: ReviewDocument12 pagesAssessment of Febrile Seizures in Children: ReviewFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Non Hodgkin LymphomaDocument35 pagesNon Hodgkin LymphomaFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Skin Colour Is Associated With Periodontal Disease in Brazilian Adults: A Population-Based Oral Health SurveyDocument6 pagesSkin Colour Is Associated With Periodontal Disease in Brazilian Adults: A Population-Based Oral Health SurveyFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- The Perceived GronroosDocument3 pagesThe Perceived GronrooskyveligPas encore d'évaluation

- National CPNS Selection Committee 2014 List of General Applicant TKD ScoresDocument71 pagesNational CPNS Selection Committee 2014 List of General Applicant TKD ScoresFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- A Corporate Character Scale To Assess Views On Org. ReputationDocument24 pagesA Corporate Character Scale To Assess Views On Org. ReputationJohn SucksterPas encore d'évaluation

- Narver & Slater - The Effect of A Market Orientation On Business ProfitabilityDocument17 pagesNarver & Slater - The Effect of A Market Orientation On Business ProfitabilityCyoko DaynizPas encore d'évaluation

- Transformation: Programme 2007-2010Document20 pagesTransformation: Programme 2007-2010Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- 6311124Document11 pages6311124Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Rs CHP PR Links Among HighDocument17 pagesRs CHP PR Links Among HighFerdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- A Corporate Character Scale To Assess Views On Org. ReputationDocument24 pagesA Corporate Character Scale To Assess Views On Org. ReputationJohn SucksterPas encore d'évaluation

- 11924953Document20 pages11924953Ferdina NidyasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Laboratorio 1Document6 pagesLaboratorio 1Marlon DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- Hydrogeological Characterization of Karst Areas in NW VietnamDocument152 pagesHydrogeological Characterization of Karst Areas in NW VietnamCae Martins100% (1)

- Position paper-MUNUCCLE 2022: Refugees) Des États !Document2 pagesPosition paper-MUNUCCLE 2022: Refugees) Des États !matPas encore d'évaluation

- Aço X6NiCrTiMoVB25!15!2 - 1.4980 Austenitic SteelDocument2 pagesAço X6NiCrTiMoVB25!15!2 - 1.4980 Austenitic SteelMoacir MachadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Antenna LecDocument31 pagesAntenna Lecjosesag518Pas encore d'évaluation

- TSS-TS-TATA 2.95 D: For Field Service OnlyDocument2 pagesTSS-TS-TATA 2.95 D: For Field Service OnlyBest Auto TechPas encore d'évaluation

- Cap 716 PDFDocument150 pagesCap 716 PDFjanhaviPas encore d'évaluation

- Health 6 Q 4 WK 6 Module 6 Version 4Document16 pagesHealth 6 Q 4 WK 6 Module 6 Version 4Kassandra BayogosPas encore d'évaluation

- History of The Stethoscope PDFDocument10 pagesHistory of The Stethoscope PDFjmad2427Pas encore d'évaluation

- Circulatory System Packet BDocument5 pagesCirculatory System Packet BLouise SalvadorPas encore d'évaluation

- MR23002 D Part Submission Warrant PSWDocument1 pageMR23002 D Part Submission Warrant PSWRafik FafikPas encore d'évaluation

- Kertas Trial English Smka & Sabk K1 Set 2 2021Document17 pagesKertas Trial English Smka & Sabk K1 Set 2 2021Genius UnikPas encore d'évaluation

- Journalize The Following Transactions in The Journal Page Below. Add Explanations For The Transactions and Leave A Space Between EachDocument3 pagesJournalize The Following Transactions in The Journal Page Below. Add Explanations For The Transactions and Leave A Space Between EachTurkan Amirova100% (1)

- Arp0108 2018Document75 pagesArp0108 2018justin.kochPas encore d'évaluation

- Simple Syrup I.PDocument38 pagesSimple Syrup I.PHimanshi SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- New930e-4se Ceam031503 930e4se Omm A31937 Up PDFDocument273 pagesNew930e-4se Ceam031503 930e4se Omm A31937 Up PDFSergelen SakhyabazarPas encore d'évaluation

- PERSONS Finals Reviewer Chi 0809Document153 pagesPERSONS Finals Reviewer Chi 0809Erika Angela GalceranPas encore d'évaluation

- Zygomatic Complex FracturesDocument128 pagesZygomatic Complex FracturesTarun KashyapPas encore d'évaluation

- ABSCESSDocument35 pagesABSCESSlax prajapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Vturn-NP16 NP20Document12 pagesVturn-NP16 NP20José Adalberto Caraballo Lorenzo0% (1)

- Dimensional Data: For Valves and ActuatorsDocument52 pagesDimensional Data: For Valves and ActuatorsPaulPas encore d'évaluation

- BS 5911-120Document33 pagesBS 5911-120Niranjan GargPas encore d'évaluation

- Frank Wood S Business Accounting 1Document13 pagesFrank Wood S Business Accounting 1Kofi AsaasePas encore d'évaluation

- B.Sc. (AGRICULTURE) HORTICULTURE SYLLABUSDocument31 pagesB.Sc. (AGRICULTURE) HORTICULTURE SYLLABUSgur jazzPas encore d'évaluation

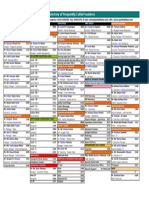

- Directory of Frequently Called Numbers: Maj. Sheikh RahmanDocument1 pageDirectory of Frequently Called Numbers: Maj. Sheikh RahmanEdward Ebb BonnoPas encore d'évaluation

- Completed Manuscript 1 5Document52 pagesCompleted Manuscript 1 5SAMANTHA LACABAPas encore d'évaluation

- Pictorial History of AOTADocument5 pagesPictorial History of AOTAThe American Occupational Therapy Association0% (4)

- DPW Series Profile Wrapping Application HeadDocument2 pagesDPW Series Profile Wrapping Application HeadNordson Adhesive Dispensing SystemsPas encore d'évaluation

- LAST CARGOES AND CLEANINGDocument1 pageLAST CARGOES AND CLEANINGAung Htet KyawPas encore d'évaluation

- Aging and Elderly IQDocument2 pagesAging and Elderly IQ317537891Pas encore d'évaluation