Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical, Biochemical, Immunological and Virological Profiles Of, and Differential Diagnosis Between, Patients With Acute Hepatitis B and Chronic Hepatitis B With Acute Flare

Transféré par

Raison D'etreTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Clinical, Biochemical, Immunological and Virological Profiles Of, and Differential Diagnosis Between, Patients With Acute Hepatitis B and Chronic Hepatitis B With Acute Flare

Transféré par

Raison D'etreDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05600.

H E PAT O L O G Y

Clinical, biochemical, immunological and virological profiles

of, and differential diagnosis between, patients with acute

hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis B with acute flare

Yongnian Han, Qun Tang, Wei Zhu, Xiaoqing Zhang and Longying You

Research Unit of Liver Disease, Shanghai No. 8 Peoples Hospital, Shanghai, China

Key words

acute hepatitis B, alpha-fetoprotein, chronic

hepatitis B, differential diagnosis, hepatitis B

virus.

Accepted for publication 24 February 2008.

Correspondence

Dr Yongnian Han, Research Unit of Liver

Disease, Shanghai No. 8 Peoples Hospital,

8 Caobao Road, Shanghai 200235, China.

Email: hanyn88@163.com

Abstract

Background and Aim: In areas with high or intermediate endemicity for chronic hepatitis

B virus (HBV) infection, it is difficult to distinguish acute hepatitis B (AHB) from chronic

hepatitis B with an acute flare (CHB-AF) in patients whose prior history of HBV infection

has been unknown. The present study aimed to screen laboratory parameters other than

immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc) to discriminate

between the two conditions.

Methods: A retrospective and prospective study was conducted in patients first presenting

clinically as HBV-related acute hepatitis to sort out acute self-limited hepatitis B (ASLHB). Then, clinical and laboratory profiles were compared between patients with ASL-HB

and CHB-AF. Parameters closely associated with ASL-HB were chosen to evaluate sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive values and negative predictive values for

diagnosing AHB.

Results: There were significant differences between patients with ASL-HB and CHB-AF

in relation to clinical and laboratory aspects, with many outstanding differences in levels of

serum HBV-DNA, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) as well as

IgM anti-HBc. In particular, there was a greater difference between the two groups in low

levels of HBeAg (ratio of the optical density of the sample to the cut-off value [S/CO] <20)

than in negativity for HBeAg (42.7% and 13.5% vs 49.3% and 45.9%). 1:10 000 IgM

anti-HBc had a sensitivity and specificity of 96.2% and 93.1%, respectively, for predicting

ASL-HB. Combining it with AFP, HBeAg or HBV-DNA could improve diagnostic power.

A combination of IgM anti-HBc, HBV-DNA and HBeAg had a predictive value of 98.9%

and a negative predictive value of 100.0%, similar to that of a combination of IgM anti-HBc

and HBV-DNA. Adding AFP to the combinations of IgM anti-HBc and HBV-DNA or

HBeAg could further heighten the positive predictive value. The positive predictive value

and negative predictive value of the combination of IgM anti-HBc, HBV-DNA and AFP

were both 100.0%.

Conclusions: (i) There are significant differences with respect to clinical, biochemical,

immunological and virological aspects between ASL-HB and CHB-AF. (ii) Of several

diagnostic combinations, IgM anti-HBc jointing HBV-DNA is most effective and most

practicable in distinguishing ASL-HB from CHB-AF. (iii) A low HBeAg level is more

useful than negative HBeAg in differential diagnosis between ASL-HB and CHB-AF. (iv)

In those patients with a high level of IgM anti-HBc, serum AFP level >10 upper reference

limit could rule out a probability of ASL-HB.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a peculiar virus, leading to both an

acute infection and a chronic one. HBV-related acute hepatitis may

be a true episode of acute hepatitis B (AHB) or an acute flare of

chronic hepatitis B (CHB) hitherto unknown. It is important to

distinguish AHB patients, a great number of whom will have a

1728

self-limited, benign course and not require intervention, from

patients with CHB with an acute flare (CHB-AF) who will

not have such a benign course and benefit from treatment with

antiviral agents.1

The presence of serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

with clinical and biochemical features of acute hepatitis usually

suggests AHB in patients from low HBV infection endemic areas

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 23 (2008) 17281733 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Foundation and Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Y Han et al.

but not in patients from high or intermediate HBV endemic

regions, where AHB and CHB-AF may be misdiagnosed mutually,

especially if patients antecedent HBV carrier status is unknown.

Immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM

anti-HBc) has been well recognized as a gold standard for

diagnosis of acute HBV infection.2,3 The commercially available

enzyme immunoassays (EIA) for IgM anti-HBc have been

designed to detect only higher titers of the antibody, but IgM

anti-HBc is present in approximately 1015% of patients with

CHB, especially in those with CHB-AF.2,3 IgM anti-HBc in high

titers had a high sensitivity (90100%) and specificity (90100%)

for the diagnosis of acute HBV infection.46 The results, however,

were obtained by comparison of acutely HBV-infected patients

with those with common CHB without an acute flare, even with

healthy individuals who were only positive for anti-HBc. When

CHB-AF was compared, IgM anti-HBc in a titer of 1:1000 had a

sensitivity of only 77.6% and a specificity of 70.0% for diagnosing

AHB.7 Although a fully automated microparticle chemiluminescent immunoassay in which significant specimen dilution and

multiple steps are avoided, has recently been developed, an ideal

cut-off value to differentiate AHB from CHB-AF seems not to be

established, because a great range (1.5, 2.42.5 and 10) of cut-off

index values have been reported in patients from Greece, Taiwan

and Italy; 9085% and 100%, respectively, regarding sensitivity

and 8690% and 99%, respectively, regarding specificity for diagnosing acute hepatitis B were shown in the two latter studies.810

However, the nearly perfect diagnostic power from Italys study

also resulted from comparison of AHB with common CHB

without acute exacerbation.10

Therefore, it is necessary to seek other parameters to assist IgM

anti-HBc to distinguish AHB from CHB-AF in patients with no

prior HBV infection history information whose diagnosis could

not be made by IgM anti-HBc alone during hospitalization. It has

been reported that HBV-DNA <0.5 pg/mL at initial presentation

had a sensitivity of 95.9% and a specificity of 86.6% for predicting

AHB in a recent study.7 Unfortunately, there were only 49 patients

with AHB in the study and the diagnostic performance of a

combination of IgM anti-HBc and HBV-DNA was not displayed.

The present large study is intended to find better methods to

discriminate the two diseases by comparison of the characteristics

of patients with ASL-HB and CHB-AF with regard to clinical,

biochemical, immunological and virological aspects.

Methods

Patients and study design

A retrospective investigation (from January 2003 to March 2005)

and a prospective study (from April 2005 to June 2006) were put

into practice in patients with their first attack of HBV-related acute

hepatitis whose status of prior HBV infection had been unknown.

HBV-related acute hepatitis was defined according to: (i) biochemical parameters: levels of serum alanine aminotransferase

(ALT) >10-fold the upper reference limit (URL), or total serum

bilirubin (TBil) >5 URL, and serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

<3 URL;11 and (ii) HBV markers: positive for serum hepatitis B

surface antigen (HBsAg), or serum antibodies to HBsAg, hepatitis

B e antigen (HBeAg), and hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg).

Hepatitis A, C, D and E, and non-viral causes, such as drugs,

Profiles and differential diagnosis of AHB

alcohol, pregnancy, ischemia, etc. that can lead to the same biochemical profiles, were all excluded. Patients who showed ultrasonographic evidence of cirrhosis were also excluded. They would

be examined retrospectively or followed up prospectively. Acute

self-limiting hepatitis B (ASL-HB) was defined as HBsAg clearing from serum after the disease remitted, or positivity for IgM

anti-HBc and for antibodies to HBsAg, HBeAg and HBcAg, with

infections with other non-hepatotropic viruses, such as human

cytomegalovirus (CMV), EpsteinBarr virus (EBV) and enteric

viruses being excluded. Alternatively, if serum HBsAg had

persisted for at least 12 months after the onset of clinically acute

hepatitis (HBsAg occasionally became undetectable until 1 year

after acute HBV infection,12 and one of our patients with ASL-HB

cleared HBsAg from serum at the 12th month after the onset of the

illness), the condition was classified as CHB.

Meanwhile, known chronically HBV-infected patients with the

same biochemical profiles as described above hospitalized during

the same period were named as CHB-AF, recruited as a control

group when other types of viral hepatitis and the above non-viral

causes were excluded, and compared with ASL-HB patients with

regard to clinical, biochemical, immunological and virological

profiles. Then, parameters with great differences and little overlap

in values were selected to assess their sensitivity, specificity,

accuracy, positive predictive value and negative predictive value

for diagnosing AHB or ASL-HB.

Data collection

Data were collected including clinical symptoms, physical signs

and laboratory examinations. The latter included: (i) biochemical

tests reflecting hepatocytic damage, such as serum TBil, ALT,

g-glutamyl transferase (GGT), prealbumin, all assayed by a colorimetric method (CSL Behring, King of Prussia, PA, USA), and

prothrombin time (PT), done as described by the manufacturers

instruction (Trinity Biotech, Wicklow, Ireland); (ii) HBV markers,

such as HBV antigens and antibodies, detected by commercially available enzyme immunoassays (Shanghai Kehua Bioengineering Co., Shanghai, China) and HBV-DNA, determined

by a fluorescent quantifying polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

method with a low limit of detection of 103 copies/mL (PG Biotech,

Shenzhen, China); (iii) alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), measured by

the electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics,

Mannheim, Germany).

For the patients in the retrospective subgroup, HBV immunological markers were recorded on the basis of inpatient and outpatient information stored in our hepatic clinic, and outpatient

information in other hospitals acquired by questionnaire or telephone visits with copies of test reports being sent to us. Those who

had no results of HBV markers were called to our clinic to undergo

the examination. For patients in the prospective subgroup, HBV

markers were determined monthly during the first 6 months or

bimonthly during the next 6 months.

Statistical analysis and diagnostic performance

of laboratory tests

Independent Students t-test was used for measurement of data,

the MannWhitneys U-test for ranked enumeration data, and the

c2-test for other enumeration data. If the expected value in any cell

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 23 (2008) 17281733 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Foundation and Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

1729

Profiles and differential diagnosis of AHB

Y Han et al.

was less than 5, Fishers exact test was used for the data suitable

for a fourfold table and MannWhitneys U-test was used for those

unsuitable for a fourfold table. All tests were two-sided and all

analyses were carried out with the SPSS version 11.5 software

package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive values, and

negative predictive values of each or combinations of parameters

screened out were calculated, respectively.

Results

Outcomes of HBV-related acute hepatitis

Of the 219 patients with HBV-related acute hepatitis, 27 of 141

in the retrospective subgroup were not located, but none of 78 in

the follow-up subgroup was lost. Of 192 patients studied, 138 were

confirmed to have ASL-HB, diagnosed by the disappearance of

serum HBsAg, whereas the remaining 54 were shown to remain

HBsAg positive after remission of the disease, diagnosed as

having CHB, including CHB to which AHB evolved, and real

CHB with acute exacerbation that had not been found before,

which is a common phenomenon in China.

Symptomatic cases were more common (95.7% vs 79.7%,

P < 0.001) in the ASL-HB group than in the CHB-AF group.

Influenza-like symptoms including pyrexia, poor appetite and

vomiting were all observed in more patients with ASL-HB than in

those with CHB-AF. As for physical signs, jaundice was found

more frequently and splenomegaly more infrequently in ASL-HB

patients than in CHB-AF patients.

Compared to those with CHB-AF, ASL-HB patients had more

severe necroinflammation of the liver, being characterized by

higher levels of serum TBil, ALT, and GGT, but less impaired

instantaneous liver functions, being characterized by higher levels

of serum prealbumin, and a shorter PT (Table 2). One of the most

remarkable findings was a difference in serum AFP levels between

the two groups. Elevated levels of serum AFP were found in fewer

patients with ASL-HB than in those with CHB-AF (26.1% vs

63.2%, P < 0.001) and, among individuals with elevation of serum

AFP, ASL-HB patients had a far lower average concentration than

did patients with CHB-AF (13.9 ng/mL vs 171.7 ng/mL,

P < 0.001), with only one of 36 (2.8%) versus 42 of 85 (49.4%) in

the two groups, respectively, having an AFP level >5 URL

(35.1 ng/mL) (P < 0.001).

Immunological and virological characteristics

Clinical and biochemical characteristics

A comparison of clinical manifestations between 138 patients with

ASL-HB and 133 patients with an acute flare of known chronic

hepatitis B (CHB-AF group) is displayed in Table 1. No differences were found in sex, age and family history of CHB between

the two patient groups.

Table 1 Patient demographics and clinical characteristics of ASL-HB

and CHB-AF

CHB-AF

(n = 133)

General profile

Age (years; mean SD)

35.9 10.9

Male/female

105/28

Family history of chronic HBV infection

None, or not known (%)

106 (79.7)

Yes (%)

27 (20.3)

Symptoms

Flu-like symptoms including pyrexia (%)

7 (5.3)

Poor appetite (%)

82 (61.7)

Abdomen distention after meals (%)

92 (69.2)

Nausea (%)

55 (41.4)

Vomiting (%)

15 (11.3)

Anorexia for greasy food (%)

12 (9.0)

Vague ache in hepatic region (%)

38 (28.6)

Lassitude and fatigue (%)

90 (67.7)

Physical findings

Jaundice (%)

75 (56.4)

Hepatomegaly (%)

22 (16.5)

Splenomegaly (%)

42 (31.6)

ASL-HB

(n = 138)

36.6 10.2

113/25

120 (87.0)

18 (13.0)

23

109

102

69

34

16

29

95

(16.7)*

(79.0)*

(73.9)

(50.0)

(24.6)*

(11.6)

(21.0)

(68.8)

129 (93.5)**

18 (13.1)

24 (17.5)*

*P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

ASL-HB, acute self-limited hepatitis B; CHB-AF, chronic hepatitis B with

acute flare.

1730

The prevalence of serum HBsAg and HBeAg was found to be

similar between the two groups, but the titers, as reflected by the

ratio of the optical density of the sample to the cut-off value

(S/CO) in the EIA method, were both lower, and the rate of HBeAg

seroconversion during hospitalization was higher in ASL-HB

patients than in those with CHB-AF (Table 3). An outstanding

finding was that HBeAg with S/CO <20 had been found in many

Table 2

Comparison of biochemical tests in ASL-HB and CHB-AF

Variable

TBil

Normal (%)

Elevated (mmol/L):

n/mean SD

ALT (URL)

GGT

Normal (%)

Elevated (URL):

n/mean SD

PT

Normal (%)

Elevated (INR):

n/mean SD

AFP

Normal (%)

Elevated (ng/mL):

n/mean SD

Prealbumin (mg/mL)

CHB-AF (n = 133)

ASL-HB (n = 138)

15 (11.3)

118/68.1 71.2

3 (2.2)*

135/109.1 82.1**

18.2 9.4

32.4 19.9**

9 (6.8)

124/3.1 2.1

5 (3.6)

133/4.1 3.7*

105 (78.9)

28/2.0 1.0

127 (92.0)*

11/2.3 1.4

49 (36.8)

84/171.7 328.2

102 (73.9)**

36/13.9 8.3**

153.6 88.7

199.4 106**

*P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ASL-HB, acute

self-limited hepatitis B; CHB-AF, chronic hepatitis B with acute flare;

GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; INR, international normalized ratio;

PT, prothrombin time; TBil, total bilirubin; URL, upper reference limit.

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 23 (2008) 17281733 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Foundation and Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Y Han et al.

Table 3

Profiles and differential diagnosis of AHB

Serological findings of ASL-HB and CHB-AF

CHB-AF

ASL-HB

HBV immunological markers**

HBsAg+, HBeAg+/anti-HBe- (%) 71 (53.4)

69 (50.0)

43 (31.2)

HBsAg+, HBeAg-/anti-HBe+ (%) 54 (40.6)

8 (6.0)

12 (8.7)

HBsAg+, HBeAg-/anti-HBe- (%)

HBsAg- (%)

0

14 (10.1)

HBsAg***, S/CO <50 (%)

31 (23.3)

64 (46.4)

HBeAg***

Negativity

61 (45.9)

68 (49.3)

S/CO <20 (%)

18 (13.5)

59 (42.7)

S/CO 20 (%)

54 (40.6)

11 (8.0)

HBeAg seroconversion* (%)

8 (11.3)

18 (26.1)

IgM anti-HBc*** (%)

Negativity

100 (76.9)

0

Positivity at 1:1000

21 (16.2)

5 (3.8)

Positivity at 1:10 000

9 (6.9)

126 (96.2)

HBV-DNA PCR quantifying

detection

Under the low limit of the

8 (6.2)

29 (22.1)

test*** (%)

122, 6.59 1.42 102, 4.53 1.23

Positivity, log10 copies/mL***

Compared with CHB-AF group: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Including patients with a negative test result.

Test was not done in seven patients with ASL-HB and in three patients

with CHB-AF in the retrospective group.

anti-HBe, antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; IgM anti-HBc, immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; ASL-HB, acute self-limited

hepatitis B; CHB-AF, chronic hepatitis B with acute flare; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B

virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; S/CO, ratio of optical density of

samples read at 450 nm to cut-off value.

more patients with ASL-HB than in those with CHB-AF (92.0% vs

59.4%, P < 0.001), with a much greater difference between the

two groups existing in patients with a low level of HBeAg (S/CO

<20) than in patients negative for HBeAg (42.7% and 13.5% vs

49.3% and 45.9%). In 131 ASL-HB patients, 126 (96.2%), five

(3.8%) and 0 were found positive for serum IgM anti-HBc in the

titer of 1:10 000, positive and negative in the titer of 1:1000,

respectively, whereas of 130 patients with CHB-AF, the numbers

were only nine (6.9%), 21 (16.2%) and 100 (76.9%), respectively.

In addition, no serum HBsAg was detected on admission in 14

(10.1%) patients with ASL-HB, which was not seen in any patients

in the CHB-AF group.

A significant difference was observed in serum HBV-DNA

levels between the two patient groups. Not only was an undetectable level of serum HBV-DNA found in more patients with

ASL-HB than in CHB-AF patients (22.1% vs 6.2%, P < 0.001),

but also the average concentration was lower in ASL-HB than in

CHB-AF patients among those with positive serum HBV-DNA

(4.53 vs 6.59 log10 copies/mL, P < 0.001).

overlapping values, were chosen. Table 4 shows differentially

diagnostic performances of each or different combinations of these

parameters calculated on the basis of 138 patients with ASL-HB

and on 133 with CHB-AF.

HBeAg with S/CO <20 (including negativity) and HBV-DNA

<105 copies/mL held a poorer sensitivity and a poorer specificity

than did 1:10 000 IgM anti-HBc (86.6%, 75.4% and 96.2%, vs

57.1%, 79.2% and 93.1%, respectively). A sensitivity of 1:10 000

IgM anti-HBc combining with AFP <5 URL, or HBeAg with

S/CO <20, or HBV-DNA <105 copies/mL, was 100.0%, 100.0%

and 98.9%, respectively; specificity was 89.4%, 90.7% and 98.9%,

respectively; a positive predictive value was 96.2%, 95.8% and

98.9%, respectively; a negative predictive value was 100.0%,

100.0% and 99.0%, respectively. A combination of IgM anti-HBc,

HBV-DNA, and HBeAg had a positive predictive value of 98.9%

and a negative predictive value of 100.0%, similar to those (98.9%

and 99.0%, respectively) of a combination of IgM anti-HBc and

HBV-DNA. Adding AFP to the combinations of IgM anti-HBc and

HBV-DNA or HBeAg could further heighten positive predictive

values. The positive predictive value and negative predictive value

of the combination of IgM anti-HBc, HBV-DNA and AFP were

both 100.0%.

Analysis of the causes of CHB

Of 192 patients studied, there were 54 patients who were classified

as having CHB because they remained HBsAg positive after the

onset of disease, except for 138 patients who were confirmed as

being ASL-HB. Does CHB evolve from acute hepatitis B or is it

actually an acute onset of unknown chronic HBV infection?

Forty-one patients were found negative and six positive for IgM

anti-HBc in a titer of 1:1000. According to the recognition that

negativity for, or a low level of, serum IgM anti-HBc can exclude

the possibility of AHB,3,5,13 these 47 patients were recognized as

having acute exacerbation of previously unrecognized HBV carriage. The remaining seven patients possessed positive IgM antiHBc in a titer of 1:10 000. Three patients were positive for HBeAg

with S/CO >20 and for HBV-DNA >107 copies/mL, and one with

the lowest level of HBV-DNA had a serum AFP level of

105.1 ng/mL (15 URL). The other two were negative for

HBeAg, one having serum AFP of 286 ng/mL and HBV-DNA of

2.46 106 copies/mL, with a typical image of chronic hepatitis by

ultrasonic examination and a few vascular spiders, congestive

palms, and the other having HBV-DNA of 5.37 106 copies/mL,

and serum AFP of 31.03 ng/mL, near 5 URL. According to our

diagnostic criteria, the probability of AHB in the preceding four

patients was ruled out and the diagnosis of CHB with a first

episode of acute hepatitis was made, and it was difficult to confirm

the diagnosis of the last patient, but a tendency for unrecognized

CHB existed. The remaining two patients had low levels of serum

HBeAg, simultaneously bearing low levels of serum HBV-DNA

and AFP, and were classified as having AHB developing into CHB.

Therefore, the chronicity rate of clinical acute hepatitis B in our

patients was 1.4% (2/140).

Discussion

Diagnostic power of laboratory parameters

According to the above analyses, four parameters, IgM anti-HBc,

HBeAg, HBV-DNA and AFP, all with great differences and little

Chronic HBV infection occurs in 8090% of infants who are

infected with HBV through vertical transmission from their

mothers or fathers, which is the most common mode of transmis-

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 23 (2008) 17281733 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Foundation and Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

1731

Profiles and differential diagnosis of AHB

Table 4

Y Han et al.

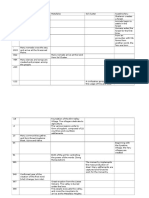

Diagnostic performance of laboratory tests for ASL-HB

Laboratory tests

Sensitivity

Specificity

Accuracy

Positive

predictive

value

Negative

predictive

value

Positive IgM anti-HBc at 1:10 000

HBV-DNA <105 copies/mL

HBeAg S/CO <20

IgM anti-HBc at 1:10 000 plus AFP <5 URL

IgM anti-HBc at 1:10 000 plus HBeAg S/CO <20

IgM anti-HBc at 1:10 000 plus HBV-DNA <105 copies/mL

IgM anti-HBc at 1:10 000 plus HBV-DNA <105 copies/mL plus HBeAg S/CO <20

IgM anti-HBc at 1:10 000 plus HBeAg S/CO <20 plus AFP <5 URL

IgM anti-HBc at 1:10 000 plus HBV-DNA <105 copies/mL plus AFP <5 URL

96.2

75.4

86.6

100.0

100.0

98.9

100.0

100.0

100.0

93.1

79.2

57.1

89.4

90.7

99.0

97.9

89.5

100.0

94.6

77.0

66.8

97.1

97.0

99.0

99.3

98.2

100.0

93.3

78.4

63.8

96.2

95.8

98.9

98.9

98.3

100.0

96.0

75.7

75.0

100.0

100.0

99.0

100.0

100.0

100.0

Including HBeAg-negative patients.

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ASL-HB, acute self-limited hepatitis B; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; IgM anti-HBc, immunoglobulin

M antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; S/CO, ratio of optical density of samples read at 450 nm to cut-off value; URL, upper reference limit.

sion for HBV in China.14,15 Thus, we have been taught that AHB is

rare in China after HBV infection has prevailed for centuries. The

lifetime risk of HBV infection, as judged by the peak prevalence of

HBV markers in elderly people, is approximately 80% in China,

but the rate of chronic HBV carriage is only 8.511.1%,14 suggesting that a great majority of HBV-infected individuals have spontaneously cleared the HBV, particularly in adults. Taking this into

consideration, we paid special attention to the follow-up care of

adult patients with a first episode of HBV-related acute hepatitis

whose previous history of HBV infection had not been known.

During the follow-up period, most of them cleared HBV from their

serum and were confirmed as ASL-HB. Sequentially, we located

and retrospectively investigated the patients who were admitted

with signs, symptoms and biochemical tests suggestive of acute

hepatitis, and were diagnosed as CHB due to evidence of HBV

infection when they were discharged from our hospital from

January 2003 to March 2005. A prospective arm on similar patients was conducted simultaneously. As we suspected, sporadic

ASL-HB is not rare but common now in China, opposite to what

has generally been accepted. So ensues a practical problem of

distinguishing AHB from CHB-AF. Here, we first compared

ASL-HB patients with CHB-AF patients in relation to clinical,

biochemical, immunological and virological aspects, and then

sought the methods to discriminate between the two diseases.

Comparison of patients with ASL-HB and CHB-AF had shown

that ASL-HB patients were more symptomatic, had a more severe

necroinflammatory liver but a more functionally compensated

liver. This finding could be explained by the fact that clinically

acute hepatitis occurred in a healthy and injured liver, respectively,

in the two conditions. Unfortunately, none of these biochemical

parameters at initial presentation could differentiate between

patients with ASL-HB and CHB-AF, which is in keeping with

Kumar et al.s observation.7

The cause of elevated AFP in patients with non-tumor liver

disease is unclear. Our findings that the peak production of a great

majority of the two groups of patients with elevated AFP levels

was observed at early phase of the disease, when liver damage was

the severest, but not at the convalescent phase (data not shown),

when hepatocytic regeneration occurred, suggest that elevations of

serum AFP in acute and chronic liver diseases may not be due to

1732

subsequent hepatocyte regeneration induced by hepatic inflammation. The literature on the mechanism of serum AFP elevation in

AHB patients is not available at the present. Longitudinal studies

showed that elevations of serum AFP levels at baseline in CHB

patients confirmed by liver biopsy had been proven to be associated with a higher risk of decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC),16,17 implying that patients with elevated serum

AFP had more advanced liver disease than did those with normal

levels. Very high levels of serum AFP suggestive of the possibility

of HCC were occasionally found in patients with chronic HBV

infection, especially those with cirrhosis, but no occurrence of

HCC.18,19 In the setting of chronic hepatitis C, the mean serum

AFP value was significantly greater in patients with more marked

fibrosis.20 All these observations put forward the hypothesis that

marked fibrosis or cirrhosis, a state of significant altered hepatocyte architecture, may be the underlying cause of increased serum

AFP and, just at the presence of fibrosis or cirrhosis, hepatocyte

necroinflammation can trigger elevations of AFP. This can explain

why AFP elevations have frequently been found in CHB patients,

with remarkable AFP elevations being associated with exacerbations of the underlying liver disease,16,21 whereas normal AFP

levels are found in a great majority of patients with ASL-HB and

only low levels of AFP in a minority of them, although they had

more severe liver necroinflammation.

As shown by other researchers,7,10 ASL-HB patients had a

higher level of serum IgM anti-HBc, lower levels of serum HBVDNA, HBeAg and HBsAg than those with CHB-AF. These phenomena can be explained by a rapid clearance of serum HBVDNA as a result of a coordinated response of innate and adaptive,

humoral and cellular immune systems in AHB.15,22 The reason why

the proportion of patients with negative HBeAg in the two groups

is similar (49.3% vs 45.9%) is that some CHB patients are infected

with HBeAg-negative variants of HBV. The finding that a low level

of serum HBeAg was observed in more patients with ASL-HB

than in patients with CHB-AF suggests that a low HBeAg level is

more useful than negative HBeAg in the differential diagnosis

between ASL-HB and CHB-AF.

Very important differences in HBV-DNA, HBeAg and AFP, as

well as IgM anti-HBc, between the two groups have been observed

in our study. When used singly, the diagnostic power for ASL-HB

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 23 (2008) 17281733 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Foundation and Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Y Han et al.

of 1:10 000 IgM anti-HBc was comparable to what has been

reported,46 whereas that of HBV-DNA <105 copies/mL was poorer

than that of HBV-DNA <0.5 pg/mL (95.9% sensitivity and 86.6%

specificity) in Kumar et al.s study.7 The discrepancy between the

two studies may stem from incomparable quantitative HBV-DNA

measurement methods and cut-off values selected.

Diagnostic performance of combinations of laboratory tests for

ASL-HB has not been seen so far and we make an attempt. Among

combinations of two parameters, 1:10 000 IgM anti-HBc uniting

HBV-DNA <105 copies/mL had the best diagnostic performance,

with a positive predictive value of 98.9% and a negative predictive

value of 99.0% and, after adding AFP <5 URL to it, both values

amounted to 100.0%. Even so, AFP is not necessarily used in

diagnosing AHB because it has only a marginal improvement

in diagnostic power in test combinations, and is not a routine test

in acute hepatitis. Alternatively, when a differential diagnosis

cannot be made, a high level (>10 URL) of serum AFP may

be helpful in ruling out the probability of AHB, according to the

observation that only one of 47 patients ASL-HB had serum AFP

level >5 URL and no patient >10 URL.

Moreover, it has been a surprise finding that a family history of

chronic HBV infection was helpful in distinguishing between

ASL-HB and CHB-AF, because, in China, a family history of

chronic HBV infection usually brings CHB to mind. Our finding is

in accordance with Thakur et al.s study in which the chronic

HBV infection rate in first-degree relatives of CHB patients was

only 29%.23

In conclusion: (i) there are significant differences with respect

to clinical, biochemical, immunological and virological aspects

between ASL-HB and CHB-AF; (ii) a low HBeAg level is more

useful than negative HBeAg in differential diagnosis between

ASL-HB and CHB-AF; (iii) a combination serum IgM anti-HBc in

a titer of 1:10 000 with serum HBV-DNA <105 copies/mL and/or

HBeAg S/CO <20 could effectively distinguish ASL-HB from

CHB-AF in patients with a first episode of HBV-related acute

hepatitis; and (iv) in those with a high level of IgM anti-HBc,

serum AFP level >10 URL could rule out the probability of

ASL-HB.

References

1 Lok ASF, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2007; 45:

50739.

2 Dufour DR, Lott JA, Nolte FS, Gretch DR, Koff RS, Seeff LB.

Diagnosis and monitoring of hepatic injury. II. Recommendations for

use of laboratory tests in screening, diagnosis, and monitoring. Clin.

Chem. 2000; 46: 205068.

3 Decker RH. Diagnosis of acute and chronic hepatitis B. In:

Zuckerman AJ, Thomas HC, eds. Viral Hepatitis. Singapore:

Harcourt Asia, 2000; 20116.

4 Lemon SM, Gates NL, Simms TE, Bancroft WH. IgM antibody to

hepatitis B core antigen as a diagnostic parameter of acute infection

with hepatitis B virus. J. Infect. Dis. 1981; 143: 8039.

5 Paraevangelou G, Poumeliotou-Karayannis A, Tassopoulos N,

Stathopoulou P. Diagnostic value of anti-HBc IgM in high HBV

prevalence area. J. Med. Virol. 1984; 13: 3939.

Profiles and differential diagnosis of AHB

6 Govindarayan S, Ashcavai M, Chau KH, Nevalainen DE, Perters RL.

Evaluation of enzyme immunoassay for anti-HBc IgM in the

diagnosis of acute hepatitis B virus infection. Am. J. Clin. Pathol.

1984; 82: 3235.

7 Kumar M, Jain S, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Differentiating acute

hepatitis B from the first episode of symptomatic exacerbation of

chronic hepatitis B. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2006; 51: 5949.

8 Tassopoulos NC, Papatheodoridis GV, Kalantzakis Y et al.

Differential diagnosis of acute HBsAg positive hepatitis using IgM

anti-HBc by a rapid, fully automated microparticle enzyme

immunoassay. J. Hepatol. 1997; 26: 1419.

9 Huang YW, Lin CL, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Kao JH, Chen DS. Higher

cut-off index value of immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis B

core antigen in Taiwanese patients with hepatitis B. J. Gastroenterol.

Hepatol. 2006; 21: 85962.

10 Rodella A, Galli C, Terlenghi L, Perandin F, Bonfanti C, Manca N.

Quantitative analysis of HBsAg, IgM anti-HBc and anti-HBc avidity

in acute and chronic hepatitis B. J. Clin. Virol. 2006; 37: 20612.

11 Dufour DR, Lott JA, Nolte FS, Gretch DR, Koff RS, Seeff LB.

Diagnosis and monitoring of hepatic injury. I. Performance

characteristics of laboratory tests. Clin. Chem. 2000; 46: 202749.

12 McMahon BJ, Alward WLM, Hall DB et al. Acute hepatitis B virus

infection: relation of age to the clinical expression of disease and

subsequent development of the carrier state. J. Infect. Dis. 1985;

151: 599603.

13 Kaganov BS, Nisevich NI, Uchaikin VF et al. Acute viral hepatitis B

in children: lack of chronicity. Lancet 1990; 336: 3745.

14 Liu X, Schinazi RF. Molecular and serum epidemiology of HBV and

HCV infection and the impact of antiviral agents in China. In:

Schinazi RF, Sommadossi JP, Rice CM, eds. Frontiers in Viral

Hepatitis. Amsterdam: Elsevier BV, 2003; 1533.

15 Hyams KC. Risks of chronicity following acute hepatitis B virus

infection: a review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995; 20: 9921000.

16 Di Bisceglie AM, Hoofnagle JH. Elevations in serum

alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Cancer

1989; 64: 211720.

17 Xu B, Hu D-C, Rosenberg DM et al. Chronic hepatitis B: a

long-term retrospective cohort study of disease progression in

Shanghai, China. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003; 18: 134552.

18 Bae JS, Park SJ, Park KB et al. Acute exacerbation of hepatitis in

liver cirrhosis with very high levels of alpha-fetoprotein but no

occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J. Intern. Med.

2005; 20: 805.

19 Yao FY. Dramatic reduction of the alpha-fetoprotein level after

lamivudine treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus

infection and cirrhosis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2003; 36: 4402.

20 Goldstein NS, Blue DE, Hankin R et al. Serum alpha-fetoprotein

levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Relationships with

serum alanine aminotransferase values, histologic activity index,

and hepatocyte MIB-1 scores. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1999; 111:

81116.

21 Lok AS, Lai CL. alpha-Fetoprotein monitoring in Chinese patients

with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: role in the early detection of

hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 1989; 9: 11015.

22 Chemello L, Mondelli M, Bortolotti F et al. Natural killer activity in

patients with acute viral hepatitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1986; 64:

5964.

23 Thakur V, Guptan RC, Malhotra V, Basir SF, Sarin SK. Prevalence

of hepatitis B infection within family contacts of chronic liver

disease patientsdoes HBeAg positivity really matter? J. Assoc.

Physicians India 2002; 50: 138694.

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 23 (2008) 17281733 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Foundation and Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

1733

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Coral of The MoonDocument33 pagesCoral of The MoonViolettaFlowerPas encore d'évaluation

- Timeline Ar TonelicoDocument43 pagesTimeline Ar TonelicoRaison D'etrePas encore d'évaluation

- 07 Eosinophilic MeningitisDocument37 pages07 Eosinophilic MeningitisMai ChanisaraPas encore d'évaluation

- survival the finalist (เน็ทน้อย) PDFDocument377 pagessurvival the finalist (เน็ทน้อย) PDFPiich Kwang100% (1)

- Clinical, Biochemical, Immunological and Virological Profiles Of, and Differential Diagnosis Between, Patients With Acute Hepatitis B and Chronic Hepatitis B With Acute FlareDocument6 pagesClinical, Biochemical, Immunological and Virological Profiles Of, and Differential Diagnosis Between, Patients With Acute Hepatitis B and Chronic Hepatitis B With Acute FlareRaison D'etrePas encore d'évaluation

- Cyanotic Heart LesionsDocument40 pagesCyanotic Heart LesionsRaison D'etrePas encore d'évaluation