Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

tmp15DB TMP

Transféré par

FrontiersDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

tmp15DB TMP

Transféré par

FrontiersDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

3

The Emergence of Language

Comprehension

MARYELLEN C. MACDONALD

1. Introduction

At the time when the first Emergence of Language volume was published (MacWhinney,

1999), many researchers in language comprehension argued that comprehension behavior was emergent from processes that weighed probabilistic information from many

sources to arrive at the most likely interpretation of linguistic input (see MacDonald

and Seidenberg, 2006, for review). For example, English speakers have no trouble understanding sentence (1) below, even though most of the words in the sentence bank, to,

cash, and check have multiple meanings and parts of speech, and the sentence even contains two different meanings of to. Given all this ambiguity, why is comprehension so

easy?

(1) I went to the bank to cash a check.

The answer from constraint-based accounts of comprehension is that ambiguity might

be overwhelming in isolation, but in the context of a broader sentence and discourse,

comprehenders can rapidly settle on what is the most likely interpretation of nominally

ambiguous input. They do so in part by favoring interpretations that are more frequent

overall (the monetary sense of bank is more frequent than its other meanings in English

as a whole), but the real power in the system comes from context-dependent processing:

check in the context of bank and cash likely refers to a bank check rather than other meanings. This view has sparked extensive research investigating the nature of the constraint

integration and the time course of weighing probabilistic information during sentence

processing. It also raises two important questions: (1) How do people learn to weigh all

the probabilities so rapidly? And (2) where do these probabilities come from?

Answers to (1) take several different forms but all involve claims in which representations (such as word meanings) vary in speed of access as a function of past use, and that

people implicitly learn the statistics of their environment, including their linguistic environment, from a very young age (e.g., Lany and Saffran, 2011). Note that environment

here may encode simple co-occurrences independent of structure or word order (such

The Handbook of Language Emergence, First Edition. Edited by Brian MacWhinney and William OGrady.

2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

82

Maryellen C. MacDonald

as the common co-occurrence of boy and girl), and these co-occurrences may be helpful

in comprehension, but many constraints are highly sensitive to knowledge about exact

word order or sentence structure, so that, for example, to is interpreted differently in

the context of went to the and to cash. Similarly, its the exact sentence environment, not

simple co-occurrences of cash and check, that guides interpretations in Ill cash a check vs.

Ill check if I have cash (see MacDonald and Seidenberg, 2006; Tanenhaus and Trueswell,

1995, for discussion of frequency- and context-sensitive comprehension mechanisms).

These issues concerning knowledge of sentence structures lead us to question (2):

Why does the language have the statistical properties it has, and not others? More specifically for sentence structures, why are some kinds of sentences much more common than

others? I began to address this question in the first Emergence of Language volume, where

I sketched three puzzles about how some aspects of language seemed to emerge from

other language domains (MacDonald, 1999). Those ideas knocked around in my head

for an embarrassingly long time, gradually acquired a broader empirical base with new

studies that my colleagues and I conducted, and eventually emerged as a more specific

account of interactions between language production, language comprehension, and

language form that I have called the ProductionDistributionComprehension (PDC)

Account (MacDonald, 2013a). The PDC claim is that language has many of the statistics

it has, and therefore constraint-based comprehension processes yield the comprehension

patterns that they do, in large measure because of the way language production works.

At some level this has to be true: language production is a necessary step in the creation

of utterances and therefore of their statistical patterns over time and over producers. But

the PDC is more than the observation that speaking produces language. It is that biases

inherent in the production process actively create important distributional regularities

in languages, which in turn drive constraint-based comprehension processes.

Before we investigate these claims more fully, it is important to define their limits.

In saying that language form and language comprehension processes owe a great deal

to language production, I do not mean that language production processes are the only

source of language form and language comprehension. The language producers aim is

to communicate a message, and so of course the producers utterance must reflect that

message. If production difficulty were the only constraint on utterance form, then every

utterance would be some easily produced grunt. Instead, the claim here is that during the

process of converting an intended message to a linguistic utterance developed to convey

that message, many implicit choices must be made for the form of the utterance, and the

production system gravitates toward those message-appropriate forms that are easier

than other forms. Thus while the message is clearly central in dictating the utterance

(the whole point of the utterance is to convey the message), language production processes themselves also shape the utterance form. Sometimes this approach is contrasted

with communicative efficiency (Jaeger, 2013; Ramscar and Baayen, 2013), but the PDC

isnt anti-efficiency; indeed it makes a prediction about how the balance between ease

of production and good communication may shake out: Because production is harder

than comprehension (Boiteau, Malone, Peters, and Almor, 2014), an efficient system is

one in which tuning utterance forms to aid production fluency is overall more efficient

than one that is tuned to the needs of the comprehender (see MacDonald, 2013a, 2013b,

for discussion).

MacDonald (2013a) summarized evidence for three biases in production, each of

which promotes the use of easier utterance forms over more difficult ones. The basic

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

83

logical chain is the following: (1) Language production (and all motor action) is controlled by a plan that is at least partially developed before it is executed. In the case of

language production, we will call this plan an utterance plan, independently of whether

the utterance plan is ultimately spoken, signed, or written.1 (2) The utterance plan must

be held in memory until it is ready to execute. (3) Language producers must monitor

the state of their utterance plan and its execution to make sure that each part of the plan

is executed at the right time, and that upcoming parts are ready to be executed. (4) An

utterance plan is essential for fluent production, but these memory and monitoring

burdens can lead to disfluency and other errors. There is therefore pressure to limit

the amount and complexity of advance planning, and so language producers learn to

plan incrementally, meaning that they plan some portion of the utterance and begin

to execute this plan (e.g. to speak) while they are simultaneously planning upcoming

portions. (5) This incremental interleaving of planning and execution is accomplished

more easily with certain utterance forms than others, and MacDonald argued for three

types of biases that tend to result in more easily planned forms in the utterance plan.

These biases reflect the essential memory demands of constructing, maintaining, and

monitoring an utterance plan. The three biases are first generally described below,

followed by examples of how they influence production patterns and comprehension

in English and other languages.

1.1 Easy First

Some words and concepts are more easily retrieved from memory than others, owing to

their greater frequency in prior experience, recent mention (givenness) in the discourse,

salience for the producer, or consistency with the producers perspective (MacWhinney,

1977), or other reasons (e.g. Bock, 1987). These forces affect the formulation of the

producers intended pre-linguistic message, with the result that linguistic elements

conveying these central aspects of the message (such as the word dog conveying

the conceptual representation of dog activated in the message) are activated more

quickly than are words or phrases for less central message components. Given incremental utterance planning, in which producers begin overt production early while

simultaneously planning upcoming portions of the utterance, it is advantageous to

place quickly retrieved elements early in the utterance plan and to begin to execute

that portion of the plan while simultaneously continuing to plan less immediately

accessible elements. This is the essence of the Easy First bias, which is also known

in the production literature as accessibility or availability. Beginning with easy material allows the producer to off-load (that is, produce) already retrieved elements

right away, while at the same time continuing to plan the more difficult (less easily

retrieved) parts of the utterance. The alternative of beginning with hard elements

is not so desirable: Initial production is delayed while waiting for the hard words

to be retrieved from memory, and the utterance plan grows large with the already

retrieved easy words. Thus overall difficulty is reduced when relatively easy elements

lead the way in the utterance plan. The account goes beyond common arguments

for the effect of salience in utterance form and grounds the effect in the nature

of retrieval from long-term memory and utterance planning, in that the salience of

some part of the message affects ease of retrieval from memory, which affects word

order (MacDonald, 2013a). The link to memory here allows the linking of salience

84

Maryellen C. MacDonald

to other memory-based effects that are not tied to noun animacy or other features of

message salience.

1.2 Plan Reuse

A key aspect of motor learning is persistence and reuse of an abstract motor plan from

a previous action: an action that has already been performed is more likely to be performed again. Thats the basic notion of Plan Reuse (also known as structural persistence

and syntactic priming). These reuse effects are found in all levels of language production, including repetition of recently perceived or produced sentence structures, words,

phrases, accents, gestures, and many other features of language production (e.g. Bock,

1986). Of most interest for us here, language producers routinely reuse sentence structures and fragments that they have recently produced or perceived, even in the absence

of overlap of words across the first and second use of some structure. In some cases, the

reuse of a structure is immediate, as when someone utters a passive sentence and then

immediately utters a second one. Such rapid reuse may reflect immediate episodic memory of a prior utterance, but other reuse is over longer periods and not so obviously from

episodic memory. Instead, plan reuse is thought to reflect long-term statistical learning

over past comprehension and production experience (Chang, Dell, and Bock, 2006).

Both the Easy First and the Plan Reuse biases reflect properties of recall from memory,

and both promote more practiced elements over less practiced ones, but the nature of

the elements differs. Easy First is a bias toward easily retrieved lexical items, whereas

Plan Reuse refers to the ease of developing an abstract plan, largely independent of the

content. Sometimes these two biases can work together, as when English speakers tend to

put animate agents in the subject position, yielding active sentences such as The girl read

the book and The teacher graded the test. Here Easy First promotes the use of animate entities

in early and prominent subject position (Bock, 1987), and Plan Reuse promotes the use

of the frequent active sentence structure with SVO word order. In other situations, the

two biases can work in opposite directions, such as when Easy First promotes the early

occurrence of some element, which results in the need for a rarer sentence structure, as

when a salient patient of some action is in the prominent subject position, yielding a

passive sentence, such as The girl was scolded by the teacher.

1.3 Reduce Interference

This third factor also reflects the memory burdens of utterance planning, though perhaps

more the burdens of short-term maintenance than retrieval from long-term memory. A

well-known phenomenon from the memory literature is that when someone has several

things to recall from memory, the elements can interfere with one another, leading to

omissions or errors in recall, particularly when the elements overlap in semantics and/or

phonology (Conrad and Hull, 1964). Because utterance plans are maintained in memory

before execution, elements in the plan can interfere with one another, just as elements in a

list can create interference when someone is trying to recall the list. Language producers

attempt to reduce this interference by omitting optional elements of the utterance or

using a word order that allows interfering elements to be distant from each other in the

utterance (Gennari, Mirkovic and MacDonald, 2012).

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

85

These three biases are only sketched here, but each of them has quite extensive empirical support within language production research.2 Though this chapter is supposed to

address the emergence of comprehension processes, its worth noting that these biases are

themselves at least in part emergent from other non-linguistic systems. These include

the nature of motor and action planning, where a plan precedes execution and must be

maintained in memory, the nature of recall from long-term memory, which is such that

some content is inherently easier to recall than other knowledge, the nature of increased

speed and fluency of action with practice, and the nature of ordering of actions in action

or motor planning, which is such that attention or queuing mechanisms order easier

actions before more difficult ones. Given all these commonalities between language production and production of other kinds of complex plans and motor sequences, it is not

surprising that non-linguistic action research also yields evidence biases that resemble

Easy First, Plan Reuse, and Reduce Interference (see MacDonald, 2013a for discussion).

Production processes require a winner-take-all system, meaning that producers must

settle on only one alternative form: we must settle on either Give Mona the book, or Give the

book to Mona, and we cannot utter some blend of the two. This winner-take-all characteristic, together with adherence to these three production biases, means that a producers

utterances will tend to favor certain forms that mitigate production difficulty over forms

that are more difficult to plan and execute. Aggregating these effects across many, many

language producers, we can see that the language as a whole will tend to have a higher

proportion of easier forms than of more difficult ones. Again, ease of production is not

the only influence on utterance form, but the argument here is that it has substantial

effects on the distributional regularities in the language. These distributional regularities

in turn are the fodder for constraint-satisfaction processes in language comprehension,

to which we turn next.

2. The Role of Language Statistics in Comprehension

Processes

From the perspective of a language comprehender, two critical features of language

input are (1) that speech input is fleeting and arrives over time, so that it is important

to interpret the input rapidly, and (2) that there are statistical dependencies between

some portion of the input and parts arriving earlier or later; encountering am going, for

example, strongly promotes the existence of the subject pronoun I earlier in the input and

increases the probability of encountering a prepositional phrase (to the store) or adverb

(now) downstream. Research from a number of different theoretical perspectives has suggested that comprehenders exploit these statistical dependencies both to refine interpretation of prior input with the newly arrived input and to predict upcoming input based

on what has already arrived (e.g., Hale, 2006; Levy, 2008; MacDonald, Pearlmutter, and

Seidenberg, 1994; MacDonald and Seidenberg, 2006; Tanenhaus and Trueswell, 1995), so

that input that is predictable in context is comprehended more quickly than unexpected

input. Much of this research has been aimed at demonstrating that comprehenders are

able to use probabilistic information extremely rapidly and that they can combine multiple probabilistic constraints in sophisticated ways. More recent studies have begun to

investigate statistical learning over combinations of distributions, in infants (e.g. Lany

86

Maryellen C. MacDonald

and Saffran, 2011) and continuing through adulthood (Amato and MacDonald, 2010;

Wells, Christiansen, Race, Acheson, and MacDonald, 2009), which allow comprehenders

to learn over the input that they have encountered. What the PDC adds to this work is a

link to the origin of the statistics used in constraint-based comprehension, in that important distributions can be traced to producers attempts to reduce production difficulty.

In the following sections, we review two classic examples in sentence comprehension,

making these links between production choices, distributions, learning, and sentence

comprehension more explicit.

3. The PDC in Syntactic Ambiguity Resolution: Verb

Modification Ambiguities

A well-known syntactic ambiguity, the verb modification ambiguity, is shown in (2), in

which an adverbial phrase could modify one of two different actions described in the

sentence. Example (2a) shows a fully ambiguous structure, (2b) shows an example in

which verb tense disambiguates the sentence in favor of the local modification interpretation, in which the adverb yesterday modifies the nearest verb left rather than the more

distant phrase will say, and (2c) is an example of distant modification, in which tomorrow

modifies the distant verb, will say.

(2) (a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Verb modification ambiguity: John said that his cousins left yesterday.

Local modification: John will say that his cousins left yesterday.

Distant modification: John will say that his cousins left tomorrow.

Equivalent message to (2c): Tomorrow John will say that his cousins left.

English comprehenders very strongly prefer to interpret ambiguous sentences like (2a)

to have the local modification interpretation (as in 2b) rather than distant modification (2c). This pattern is often thought to arise directly from innate syntactic parsing

or memory biases to favor local phrasal relationships over long-distance ones, variously formulated as Right Association (Kimball, 1973), Late Closure (Frazier, 1987), and

Recency (Gibson, Pearlmutter, Canseco-Gonzalez, and Hickok, 1996). A key assumption has been that these parsing principles operate on purely syntactic representations

without lexical content (e.g., Frazier, 1987). This approach accorded well with the fact

that, with few exceptions (Altmann, van Nice, Garnham, and Henstra, 1998; Fodor and

Inoue, 1994), the lexical content of sentences like (2) has minimal effect on English speakers strong bias in favor of local modification, making verb modification ambiguities the

best available evidence for lexically independent innate parsing algorithms that operate

over abstract syntactic structures.

As Table 3.1 summarizes, the PDC approach accounts for the local interpretation

biases without innate parsing algorithms. Instead the effects emerge from comprehenders learning over the distributional regularities in the language, which in turn stem

from the biases of producers to favor certain sentence forms that minimize production

difficulty.

In Step 1 in the table, the Easy First production bias discourages production of distant

modification sentences like (2c) because more easily planned alternatives exist. In (2c),

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

87

Table 3.1. ProductionDistributionComprehension (PDC) account of greater comprehension difficulty for ambiguities resolved with distant modification (2c) than with

local modification (2b). Modified from MacDonald, 2013a

PDC steps

1

Production

Easy First, where shorter phrases precede longer ones,

discourages production of ambiguous structures like (2a) with

intended distant modification (2c), and instead promotes

production of other forms to convey the same message (2d)

(MacDonald, 1999; MacDonald and Thornton, 2009).

Distribution

Comprehension

As a result, ambiguous sentences with intended distant

modification are much rarer than ambiguous sentences

resolved with local modification (MacDonald and Thornton,

2009; Sturt, Costa, Lombardo, and Frasconi, 2003).

The comprehension patterns reflect the language statistics in

Step 2:

a. Overall, the rarer distant modification sentences are harder

than the more common local modification sentences

(Altmann et al., 1998; MacDonald and Thornton, 2009).

b. However, a subtype of verb modification ambiguities does

not violate Easy First in its distant modification form, owing

to the relative length of phrases in these sentences. These are

readily produced by speakers who intend distant modification, are common in the language, and are easily comprehended (MacDonald and Thornton, 2009).

a relatively long phrase (that his cousins left) precedes a short one (yesterday), but Easy

First promotes a short-before-long phrase order, as in (2d) or John said yesterday that

his cousins left. Step 2 identifies the distributional consequences of speakers avoiding

utterances like (2c): in comprehenders previous experience, ambiguous sentences

like (2a) overwhelmingly are associated with a local modification interpretation like

(2b). Comprehenders learn these statistics and are guided by them in interpretation

of new input (Step 3). They have difficulty comprehending largely unattested forms

like (2c), but they readily comprehend the special type of distant modification sentences that dont violate Easy First and that do exist in the language. These sentences,

such as the examples in (3) (with brackets to indicate the local vs. distant modification), are ones in which the modifier (very slowly) is longer than the embedded

verb phrase (swimming), so that the Easy First short-before-long bias promotes a

verb verb modifier structure independent of whether a local or distant interpretation

is intended.

(3) (a) Local modification

(b) Distant modification

Mary likes [swimming [very slowly]]

Mary [likes [swimming] very much]

88

Maryellen C. MacDonald

For these special cases in which distant modification is common in past experience,

comprehenders can readily interpret ambiguities with either the local or the distant modification interpretation, as dictated by the lexical and discourse context. Its even possible

to find ambiguous sentences of this type in which comprehenders initially strongly prefer the distant modification interpretation, something that should never happen if there

is an innate parsing bias toward local modification. An example is in (4), which is a

quote from US Supreme Court Chief Justice John Robertss majority opinion (original

available at http://www.supremecourt.gov/, opinion date June 26, 2013). As the bracketing shows, the embedded verb phrase to do so is shorter than the modifier for the first

time here, and so the word order in (4a) is the preferred one, independent of the writers

intended interpretation. Upon reading the ambiguous version in (4a), a tempting interpretation is (4b), in which the court had declined for the first time to do something.

The broader context makes it clear that the correct interpretation is instead the local

modification in (4c), where the doing something is for the first time. I havent made

a study of what lexical statistics, such as past co-occurrences of decline and temporal

expressions like for the first time, might promote the incorrect interpretation here, but

the point is clear that the existence of sentences like this, together with the empirical

data from MacDonald and Thornton (2009), argue against an innate comprehension

bias for local modification. Instead, comprehenders have a learned bias toward what

has happened in the past, and that this prior linguistic experience owes to aspects of

production planning.

(4) (a) Original ambiguous sentence: We decline to do so for the first time here.

(b) Distant modification:

We [decline [to do so] for the first time here].

(c) Local (intended) modification: We [decline [to do so for the first time here]].

This claim for the role of past experience in subsequent comprehension processes is at the

heart of constraint-based accounts of language comprehension, which have been applied

to many other syntactic ambiguities (MacDonald and Seidenberg, 2006; Tanenhaus and

Trueswell, 1995). The added value of the PDC is, first, a greater emphasis on the role of

learning probabilistic constraints (e.g., Amato and MacDonald, 2010; Wells et al., 2009),

and, second, an account of the production basis for many of the language distributions

that people learn and use to guide comprehension. Extending the PDC to other syntactic

ambiguities is ongoing; the approach holds promise because (1) these ambiguities turn

on the relative frequency of alternative uses of language, which can be readily learned

from input (Wells et al., 2009), and (2) certain production choices affect syntactic ambiguity. For example, variation in availability of genitive forms (the professors daughter vs.

the daughter of the professor) in English vs. other European languages affects the distribution of noun modification ambiguities and their interpretation in these languages

(see Mitchell and Brysbaert, 1998, for review and Thornton, MacDonald, and Gil, 1999,

for constraint-based studies of cross-linguistic similarities and differences). Similarly,

producers manage production demands through the use of optional words (e.g. V. Ferreira and Dell, 2000), which have substantial effects on ambiguity, the distribution of

formmeaning pairings, and consequent experience-driven ambiguity resolution processes. Thus the PDC prediction is that all syntactic ambiguities can ultimately be traced

to producers implicit utterance choices (at least some of which are in the service of

reducing utterance planning difficulty), the consequent distributions in the language,

and comprehenders learning over those distributions.

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

89

4. Production and Comprehension of Relative Clauses

In this section, we consider how the three production biases, Easy First, Plan Reuse, and

Reduce Interference, affect the nature of relative clause production in English and several

other languages. Relative clauses are an especially good choice to investigate the PDC

claims because all three biases interact in interesting ways and because the comprehension of relative clauses is a topic of immense interest in sentence comprehension, and

patterns of comprehension have also been used to argue for key positions in linguistics.

A reconceptualization of relative clause interpretation would therefore have enormous

consequences for sentence comprehension and linguistic theory.

Relative clauses are clauses that modify a noun phrase. By definition, they contain

at least a verb and often a subject and an object. There are several different types, of

which two have been the most heavily studied in language comprehension research:

subject relatives and object relatives. An example of each is in (5). In (5a) the book is being

modified by the bracketed relative clause; because the book is the object of the relative

clause verb (found), this structure is called an object relative clause. A subject relative

clause is illustrated in (5b), where woman is the subject of the relative clause verb wrote.

These two examples dont seem to pose much difficulty to the reader, but in fact subject

and object relative clauses have played a central role in defining the differences between

language competence and performance in generative linguistics. They have also had an

enormous impact in essentially every area of comprehension research, from acquisition,

to adult comprehension, to studies of aphasia and other language impairments.

(5) (a) Object relative: The book [that I found at the thrift shop] was about marsh

ecosystems.

(b) Subject relative: The woman [who wrote it] turns out to be my next-door

neighbor.

The origin of relative clauses importance can be traced to claims by Miller and Chomsky

(1963), who observed that the repeated recursive operation of embedding one object relative inside another one yielded an uninterpretable sentence. For example, the rat [the

cat [the dog chased] ate]died (from Newmeyer, 1998) is so impenetrable that many people dont notice that the rat doesnt seem to have died until after it was eaten. Miller

and Chomsky (1963) pointed to a distinction between linguistic competence and ability

to use that knowledge: linguistic performance is their explanation for the difficulty of

these sentences. They argued that while linguistic competence (in our case, recursion)

is infinite, performance, specifically the ability to use this knowledge to comprehend

center-embedded structures, is constrained by limitations on short-term memory capacity (Miller, 1956). In the case of object relative clauses, the memory burden stems from the

multiple incomplete nounverb dependencies arising as the sentence unfolds, so that

the comprehender must first anticipate a verb for each noun (the rat the cat the dog) and

hold these unintegrated nouns in memory, and then when the verbs are encountered

(chased ate died), associate them appropriately with the nouns (Wanner and Maratsos,

1978; Gibson, 1998). By contrast, the more comprehensible English subject relatives interleave nouns and verbs, reducing the memory burdens: The dog [that chased the cat [that

ate the rat]] died.

90

Maryellen C. MacDonald

In the years since those initial observations, relative clauses have made a mark on virtually every facet of language comprehension research. One reason is Miller and Chomskys (1963) argument for a competenceperformance distinction of infinite capacity for

recursion, but constrained in practice by working memory limitations. Several other factors also promoted the prominence of relative clauses in comprehension work. First,

relative clauses are widely held to be syntactically unambiguous (Babyonyshev and Gibson, 1999), so that comprehension difficulty cant be attributed to ambiguity resolution

processes. Second, subject and object relatives can be made to differ by only the order

of two phrases, as in the order of the senator and attacked in (6ab), so that researchers

can contrast comprehension of sentences for which the lexical content seems perfectly

matched. The vast majority of a very large number of studies in English and many other

languages, across children, adults, and individuals with brain injury, disease, or developmental atypicality, show that object relatives are more difficult than their matched

subject relatives (see OGrady, 2011, for review). The logic here seems perfectly clear:

Because the difference in difficulty cant be ascribed to lexical factors or ambiguity resolution, it must reflect purely syntactic operations and the memory capacity required to

complete them (Grodner and Gibson, 2005).

(6) (a) Object relative: The reporter [that the senator attacked] admitted the error.

(b) Subject relative: The reporter [that attacked the senator] admitted the error.

This competenceperformance account of working memory overflow in relative clause

comprehension continues as the dominant perspective in linguistics, language acquisition, adult psycholinguistics, and communicative disorders, despite criticisms of each

of the components of this argument. These criticisms include evidence that multiply

center-embedded sentences need not be incomprehensible (Hudson, 1996), that comprehension difficulty is strongly influenced by the words in the sentence and therefore

cannot reflect purely syntactic processes (Reali and Christiansen, 2007; Traxler, Morris

and Seely, 2002), that object relatives do contain a non-trivial amount of ambiguity

directly related to comprehension difficulty, again refuting the assumption that relative

clauses provide a pure measure of syntactic difficulty (Gennari and MacDonald, 2008;

Hsiao and MacDonald, 2013), that the degree of prior experience with object relatives

predicts comprehension success in children and adults, a result not captured by memory

overload approaches (Roth, 1984; Wells et al., 2009), that peoples comprehension capacity for recursive structures is more accurately described by a system in which working

memory is inseparable from linguistic knowledge than by one with separate competence and performance (Christiansen and Chater, 2001), and that, cross-linguistically,

relative clause complexity does not always predict comprehension difficulty (Carreiras,

Duabeitia, Vergara, de la Cruz-Pava, and Laka, 2010; Lin, 2008). The resilience of memory overflow accounts in the face of these myriad challenges in part reflects the essential

usefulness of the constructs of working memory capacity and competenceperformance

distinctions in cognitive science. However, a second factor is that there has been no

really compelling alternative account that captures both the subject-object relative

asymmetry as well as these other phenomena. The PDC approach aims to provide

exactly this.

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

91

5. The PDC Approach to Relative Clauses

In this section, we consider how the three production biases, Easy First, Plan Reuse, and

Reduce Interference, affect the nature of relative clause production in English and several other languages. My colleagues and I have studied production of relative clauses

both in corpus analyses of natural language and in several types of different laboratory experiments. Our work has addressed the circumstances under which producers

do and do not utter object relative clauses. The production side of the PDC is all about

producers available choices of alternative utterance forms, and we observed that producers who want to convey a message with an object relative clause could also (typically

unconsciously) choose an alternative form, a passive relative (which is a form of subject

relative). Some examples are in (7).

(7) (a) Active (object) relative clause: The toy that the girl is hugging

(b) Passive relative: The toy thats being hugged by the girl

Given our goal of linking comprehension difficulty to language distributions and ultimately production choices, an aim in our relative clause research has been to investigate

producers choices of object relatives vs. passive relatives (e.g. (7a) vs. (7b)), the factors

that motivate these choices, and the consequences for relative clause comprehension.

Many of our studies have used a picture description task in which participants view

a cartoon scene depicting several people and events and answer questions about the

picture; we structure the task and the pictures so that peoples responses often contain

relative clauses, though we never explicitly instruct them to use relative clauses and

never mention relative clauses at all. The use of pictures increases consistency of topic

across multiple speakers, and it also allows us to present the same materials and tasks to

speakers of different languages (e.g., Gennari, Mirkovic, and MacDonald, 2012; Montag

and MacDonald, 2009). In the experiment, participants see a picture with several people

and objects. After a few seconds to inspect a scene, participants hear a question about

some pictured entity that is being acted on in the picture. Half of the time, the question

refers to an inanimate entity, such as What is white? referring to a toy (a stuffed bear)

that a girl is hugging, and half of the time, the question presented to the participant refers

to an animate entity, such as a man being hugged by a girl. Participants then answer the

question. The scenes are designed to have several entities of the same type, such as several toys, so that simply saying The toy in reply to What is white? does not provide a

felicitous answer. We also provide instructions that discourage spatial descriptions such

as The toy on the right, and so speakers often produce relative clauses in order to

provide an informative answer to the question.3

A key manipulation in these studies is the animacy of the entity being described; thus

we have the question What is white? eliciting an answer identifying the toy being

hugged, and on other occasions the same scene is paired with the question Who is

wearing green?, which refers to the elderly man being hugged. The animate/inanimate

status of what is to be described has an enormous influence on producers choices of

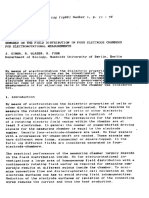

utterance form. Figure 3.1 shows the percentage of active object relatives (like 7a) that

people produce in six languages when describing animate and inanimate elements of

92

Maryellen C. MacDonald

% Active Object Relatives Produced

100

Describing animates

Describing inanimates

80

60

40

20

0

English

Spanish

Serbian

Japanese

Language

Korean

Mandarin

Figure 3.1. The frequency with which object relative clauses are produced to describe animate

and inanimate entities in a picture description task, calculated as a percentage of all relative

clauses produced. The English, Spanish, and Serbian data are from Experiments 1a, 2, and 3

respectively of Gennari et al. (2012). The Japanese data are from Montag and MacDonald (2009),

Korean from Montag et al. (in preparation), and Mandarin from Hsiao and MacDonald (in

preparation)

our pictures. These percentages are calculated over all relative clause responses, so the

percentage of passive relatives (as in 7b) is the inverse of the object relatives shown in

the graph.

Figure 3.1 shows that in six diverse languages, when people are describing something inanimate (e.g., toy), they readily produce object relatives like (7a), but they almost

never do so in describing something animate (man). Instead, they utter passive relatives

like (7b). This result holds across head direction: English, Spanish, and Serbian have a

head-first relative clause structure in which the noun being described precedes the relative clause, as in the toy [that the girls hugging], while Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin

have a head-final [relative clause] head-noun structure. The effect also holds over wide

variation in case marking: Serbian, Japanese, and Korean have extensive case marking

on the nouns, while the other three languages have little or none. Perhaps most interesting for our purposes here, active object relatives and passive relatives have identical

word order in Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin (the passive is indicated by a passive

morpheme on the verb or at the start of a relative clause), and its clear from Figure 3.1

that the animacy effects hold in these cases as well as they do in the three Indo-European

languages, for which word order does differ in the two relative clause types.

These results raise two important questions within the PDC: why does animacy have

these strong effects, and what are the consequences for comprehension? Both of these

questions are addressed in Table 3.2. Step 1 in this table describes how producers use

of object relatives vs. passive relatives is shaped by the joint action of Easy First, Plan

Reuse, and Reduce Interference biases in production planning. On this view, animate

nouns are more likely to be in passive constructions not simply because they are more

conceptually salient and more quickly retrieved from memory (as in Easy First) but

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

93

Table 3.2. PDC account of greater comprehension difficulty for object than subject relative clauses (citations refer to English results). Modified from MacDonald 2013a

1

Object relatives (7a) are common when the noun being described is inanimate

(toy) but are avoided when the relative clause describes something animate (boy),

for which passive relatives (7b) are produced instead (Gennari et al., 2012;

Montag and MacDonald, 2009). These patterns are owed to at least three

production biases:

a. Easy First: animate nouns are conceptually prominent and easily retrieved from

memory, leading to their position in early or prominent sentence positions. The

passive relative (7b) allows the described noun to be in the prominent subject

position of the relative clause.

b. Plan Reuse: the rate of passive relatives varies with the viability of passives in

the language more generally, reflecting the reuse of passive forms from other

sentence types (Montag and MacDonald, 2009).

c. Reduce Interference: there is more interference between conceptually similar entities (e.g. two animate nouns as in man/girl in the hugging picture in

Figure 3.1) than there is when an animate entity (girl) acts on an inanimate one

(toy). This interference can be reduced by omitting the agent in the utterance

plan, which is possible in passive forms (7b), but not in object relatives (7a). The

higher the conceptual similarity between sentence participants in the event to be

described, the more speakers produce passive agent-omission relative clauses

(Gennari et al., 2012).

2

3

People readily learn these correlations between animacy and relative clause type

(Wells et al., 2009).

Comprehenders who encounter the start of a relative clause have very different

expectations of how it will end, depending on whether something animate or

inanimate is being described, with consequences for comprehension:

a. When relative clauses describe something inanimate like toy, English speakers

rapidly anticipate an object relative (7a); for animates (boy), object relatives are

vanishingly rare and are not expected by comprehenders (Gennari and MacDonald, 2008).

b. The less producers are willing to say an object relative to convey a particular

message, the less comprehenders expect one, and the more difficult the comprehension is when a sentence in fact turns out to contain an object relative

clause (Gennari and MacDonald, 2009).

also because the passive construction allows producers to omit mention of the agent

of the action, in that they can omit the by-phrase (e.g., by the girl) in the passive (7b),

but this omission is not an option in object relatives like (7a). Of course speakers can

choose agentless constructions for rhetorical reasons, perhaps the best-known of which

is exemplified by the responsibility-ducking Mistakes were made. My colleagues and

I have argued that in addition to these situations in which agentless structures are chosen

94

Maryellen C. MacDonald

to convey a particular message, agent omission also has a difficulty-reduction function within language production, specifically allowing the producer to reduce the memory interference that arises when two semantically similar entities, such as man/girl, are

part of the message to be conveyed. Gennari, Mirkovic, and MacDonald (2012) found

these agent-omission effects in English and Spanish (where both the passive and a second structure permit agent omission). They showed that these agent-omission effects

stemmed not from animacy per se but from the semantic overlap of entities that arises

when both an agent and a patient are animate. In both languages, they manipulated the

similarity of animate entities interacting with one another in pictures and found that the

more similar the agent and a patient are, the more likely speakers were to omit the agent

in their utterance.

These results suggest that utterance planning difficulty affects utterance form. That

is, the passive bias for animate-headed relative clauses is not simply an effect of how the

producer frames the message to be conveyed (though that also has an effect on utterance form). Instead, the passive usage shown in Figure 3.1 also reflects the operations

of the language production system, so that ease of retrieval from long-term memory,

and the maintenance processes within working memory, shape the utterance choices

that speakers make. These results may help to tease apart alternative hypotheses concerning more egocentric production (in which production choices aid the producer) and

audience design, in which utterance forms are chosen to aid the comprehender. Communication clearly requires elements of both (see Jaeger, 2013; MacDonald, 2013a, 2013b),

but the agent-omission data appear to be evidence for a production-based motivation for

utterance form. That is, semantic similarity is known to impair recall in memory tasks

and to increase speech errors in production studies (see MacDonald, 2013a), suggesting that there are real production costs to planning an utterance containing semantically

similar items. Our data suggest that producers mitigate this cost by choosing a structure

in which they can omit one of the semantically overlapping entities. Although more

research is needed, its less obvious how these choices could help the comprehender;

semantic relationships in a sentence are often thought to have a facilitative effect, as in

priming, and so eliminating these semantic associations wouldnt seem beneficial.

We are just beginning to understand the factors behind the patterns in Figure 3.1,4

but it is clear that speakers very different choices for animate-describing and

inanimate-describing relative clauses have robust effects on the distributional regularities in these languages. Steps 23 of Table 3.2 show the cascade of consequences of

these choices. As described in Step 2, comprehenders who are exposed to the distributional regularities in their linguistic input implicitly learn the co-occurrences between

discourse environments, words, and sentence structure, so that, for example, they come

to expect object relative clauses modifying inanimate entities like toy but they do not

expect this structure modifying animate entities like man. Step 3 in the table reviews

how comprehenders rapidly bring this information to bear in comprehension, so that

people expect object relatives where theyre commonly produced but are surprised

by them in unexpected environments, leading to comprehension difficulty. The vast

majority of studies demonstrating the difficulty of object relatives have used materials

in which something animate is being described the very situation that producers

avoid and that comprehenders have learned not to expect. Gennari and MacDonald

(2008) showed that when readers encounter text that might be an animate-headed object

relative clause, such as The reporter that the senator , they expect the text to continue

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

95

with some other construction, such as The reporter that the senator had said was an idiot

didnt show up for work, and they have difficulty comprehending these sentences when

they turn out in fact to be object relative clauses, as in The reporter that the senator attacked

admitted the error. Gennari and MacDonald (2009) further tied these results to production

patterns: comprehenders dont expect animate-headed relative clauses to turn out to

be object relatives precisely because theyre almost never produced. Together, these

results suggest that object relative clause comprehension is simply another example

of ambiguity resolution comprehenders rely on past experience with relative clauses

to guide their interpretation of new ones, and it is this reliance that leads to incorrect

expectations for the unusual sentences that populate psycholinguists experiments.

The results do not reflect any pure effect of syntactic complexity on comprehension

(Gennari and MacDonald, 2008).5

On this view, relative clauses, which have been central to current conceptions of

memory and language use in virtually every subfield of psycholinguistics, turn out to

be wholly unsuited for that role, as they are not unambiguous, and their comprehension

reflects detailed knowledge of correlations between words and structures, not abstract

syntactic representations and putative burdens of holding abstract structures in memory. What then becomes of working memory limitations as a source of comprehension

difficulty, particularly within Miller and Chomskys (1963) competenceperformance

claims for infinite recursion limited by working memory? The short answer is that

researchers may further debate competenceperformance distinctions, but relative

clauses should no longer be offered as evidence of overflow of syntactic memory

representations that limit infinite recursive capacity. A more precise answer about

implications of the relative clause work requires closer attention to what working

memory is and isnt. In saying that the PDC account refutes claims for working

memory limitations in sentence comprehension, my colleagues and I do not mean

that working memory doesnt exist: to the contrary, a prime reason why language

users track the statistics of the language and use them to anticipate upcoming input

is precisely because language comprehension requires significant memory capacity,

and generating expectations for likely outcomes reduces these burdens. However, we

do reject the notion that peoples working memory capacity can be described as a

performance limitation independent of their linguistic knowledge/competence (Acheson

and MacDonald, 2009; MacDonald and Christiansen, 2002; Wells et al., 2009). Our

position reflects broader trends linking working memory and long-term knowledge

(Cowan, 2005), emergent from the temporary maintenance needs of other cognitive

processes (Postle, 2006). Specifically for relative clauses, comprehension capacity varies

with long-term knowledge of these structures, derived from experience. Language

producers provide some kinds of experiences (some kinds of relative clauses) more than

others, with consequences for language distributions, learning over those distributions,

and for the memory demands needed to comprehend these structures: the memory

capacity and experience cannot be separated. Of course computational limitations,

including memory limitations, are also at the heart of the PDC argument for why

producers prefer some utterance forms over others, but this does not mean that the

competenceperformance distinction can simply be shifted to production, because,

again, linguistic working memory, specifically the capacity to produce certain utterance

forms, is not separate from long-term linguistic knowledge or experience (Acheson and

MacDonald, 2009).

96

Maryellen C. MacDonald

6. Emergence in Comprehension, and in Production Too

This chapter has included two examples of how comprehension behavior that is

commonly thought to stem from innate parsing principles and memory representations

can be traced instead to the nature of language production. In the first example, a

classic syntactic ambiguity the verb modification ambiguity illustrated in (2) has

repeatedly been argued to be preferentially interpreted with local verb modification

either via innate parsing biases or innate memory biases (recency effects). I argued that

this interpretation bias was instead emergent from the distributional regularities in

the language that people are biased toward local modification for those subtypes of

the construction for which local modification is frequent in the language, and they do

not have this bias for other subtypes of the construction in which local modification is

not the dominant interpretation in past experience. I further argued that these distributional regularities can be traced to production patterns that stem from producers

following the Easy First word order, which in this case promotes the production of

short phrases before long ones. Thus comprehension patterns emerge from learning

over distributional regularities that themselves emerge from production biases. And

the chain doesnt stop there: MacDonald (2013a) argued that these production biases

themselves emerge from basic properties of action and motor planning in which simpler

plans are gated (via attention systems) to be executed earlier than more complex plans.

The second example, relative clause production, is more complex but follows the

same argument: comprehension patterns are emergent from learning over distributional

regularities in the language which are themselves emergent in a significant degree

from producers following the three production biases, in an attempt to reduce the

computational burdens of production planning. Ascribing a central role to production

demands does not mean that communicative goals do not also play a role in shaping the

utterance they must. However, a critical component of meeting those communicative

goals is producing utterances fluently and soon enough to keep a conversation going,

and the production biases appear to be central to achieving those goals. It will take

some time to test the PDC approach in other constructions and languages, but in the

meantime, the availability of extensive language corpora in many languages permits

comprehension researchers to examine the relationship between production patterns

(in the corpus) and comprehension behavior, even if they have not yet investigated

the production pressures that create the distributional regularities that are observed

in a corpus. The PDC suggests that it is essential to investigate such linkages before

declaring that comprehension behavior owes to highly specific design features in the

language comprehension system.

NOTES

1 The modality of the utterance (spoken, signed, texted, etc.) does have effects on the utterance plan

but we will ignore modality-specific influences here.

2 Examples of research on Easy First/Accessibility are: Bock, 1987; F. Ferreira, 1991; McDonald,

Bock and Kelly, 1993; Tanaka, Branigan, McLean, and Pickering, 2011. For discussion of Plan

Reuse/Syntactic Priming, see Bock, 1986, and Pickering and V. Ferreira, 2008. For discussions of

Reduce Interference see: Fukumura, van Gompel, Harley, and Pickering, 2011; Gennari, Mirkovic,

and MacDonald, 2012; and Smith and Wheeldon, 2004.

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

3

97

A few of these studies had written questions and written replies by participants rather than spoken

questions and responses. There have been no substantial differences in the proportions of structures

uttered in written and spoken versions of our studies to date.

One difference not discussed here is variation in the overall rate of object relatives in Figure 3.1, for

example why Serbian speakers prefer object relatives to passives to a much greater extent than do

speakers of the other languages in the figure. Although a definitive answer to this question awaits

additional research, Gennari et al. (2012) pointed to two properties of Serbian that may affect the

rate of passive usage. First, Serbian has obligatory case marking on the relative pronoun, which is

placed before the rest of the relative clause. The need to utter the case-marked form forces speakers to

commit to a relative clause form before beginning to utter it, and this early commitment may affect

passive usage. Second, Serbian has a greater freedom of word order within relative clauses than

the other languages in Figure 3.1. Gennari et al. observed some Serbian word order variations as a

function of noun animacy, and it may be that where speakers of other languages alternate between

structures, Serbian speakers alternate between word orders as a function of animacy or other factors.

Again, exactly why these patterns obtain is not yet clear.

A fuller treatment than is presented here would include the fact that object relatives with pronoun

embedded subjects (The boy/toy she splashed ) have different production biases, different rates of

production, and different comprehension patterns than the examples discussed here. We must also

consider whether Easy First, Plan Reuse, and Reduce Interference provide an adequate account of

why multiply embedded object relatives, like Miller and Chomskys (1963) The rat [that the cat [that the

dog chased] ate] died, are essentially never produced, and the extent to which comprehension difficulty

here can also be traced to ambiguity resolution gone awry rather than to hard limits on working

memory capacity.

REFERENCES

Acheson, D. J. and M. C. MacDonald. 2009.

Verbal working memory and language

production: Common approaches to the serial

ordering of verbal information. Psychological

Bulletin 135(1): 5068. doi:10.1037/a0014411.

Altmann, G. T. M., K. Y. van Nice, A. Garnham,

and J.-A. Henstra. 1998. Late closure in

context. Journal of Memory and Language 38(4):

459484. doi:10.1006/jmla.1997.2562.

Amato, M. S. and M. C. MacDonald. 2010.

Sentence processing in an artificial language:

Learning and using combinatorial constraints.

Cognition 116(1): 143148. doi:10.1016

/j.cognition.2010.04.001.

Babyonyshev, M. and E. Gibson. 1999. The

complexity of nested structures in Japanese.

Language 75(3): 423450.

Bock, J. K. 1986. Syntactic persistence in

language production. Cognitive Psychology

18(3): 355387. doi:10.1016

/0010-0285(86)90004-6.

Bock, K. 1987. An effect of the accessibility of

word forms on sentence structures. Journal of

Memory and Language 26(2): 119137.

doi:10.1016/0749-596X(87)90120-3.

Boiteau, T.W., P.K. Malone, S. A. Peters, and

A. Almor. 2014. Interference between

conversation and a concurrent visuomotor

task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General

143(1): 295311. doi: 10.1037/a0031858.

Carreiras, M., J. A. Duabeitia, M. Vergara, I. de

la Cruz-Pava, and I. Laka. 2010. Subject

relative clauses are not universally easier to

process: Evidence from Basque. Cognition

115(1): 7992. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2009

.11.012.

Chang, F., G. S. Dell, and K. Bock. 2006.

Becoming syntactic. Psychological Review

113(2): 234272. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.113

.2.234.

Christiansen, M. H. and N. Chater. 2001.

Connectionist psycholinguistics: Capturing

the empirical data. Trends in Cognitive Sciences

5(2): 8288.

Conrad, R. and A. J. Hull. 1964. Information,

acoustic confusion and memory span. British

Journal of Psychology 55: 429432.

Cowan, N. 2005. Working Memory Capacity. New

York: Psychology Press.

Ferreira, F. 1991. Effects of length and syntactic

complexity on initiation times for prepared

utterances. Journal of Memory and Language

30(2): 210233. doi:10.1016/0749-596X(91)

90004-4.

98

Maryellen C. MacDonald

Ferreira, V. S. and G. S. Dell. 2000. Effect of

ambiguity and lexical availability on syntactic

and lexical production. Cognitive Psychology

40(4): 296340. doi:10.1006/cogp.1999.0730.

Fodor, J. D. and A. Inoue. 1994. The diagnosis

and cure of garden paths. Journal of

Psycholinguistic Research 23(5): 407434.

Frazier, L. 1987. Theories of sentence processing.

In J. Garfield (ed.), Modularity in Knowledge

Representation and Natural-Language Understanding, pp. 291307. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Fukumura, K., R. P. G. van Gompel, T. Harley,

and M. J. Pickering. 2011. How does

similarity-based interference affect the choice

of referring expression? Journal of Memory and

Language 65(3): 331344. doi:10.1016

/j.jml.2011.06.001.

Gennari, S. P. and M. C. MacDonald. 2008.

Semantic indeterminacy in object relative

clauses. Journal of Memory and Language 58(4):

161187. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2007.07.004.

Gennari, S. P. and M. C. MacDonald. 2009.

Linking production and comprehension

processes: The case of relative clauses.

Cognition 111(1): 123.

doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2008.12.006.

Gennari, S. P., J. Mirkovic, and M. C.

MacDonald. 2012. Animacy and competition

in relative clause production: A

cross-linguistic investigation. Cognitive

Psychology 65(2): 141176.

doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.03.002.

Gibson, E. 1998. Linguistic complexity: Locality

of syntactic dependencies. Cognition 68: 176.

Gibson, E., N. Pearlmutter, E. Canseco-Gonzalez,

and G. Hickok. 1996. Recency preference in

the human sentence processing mechanism.

Cognition 59(1): 2359.

doi:10.1016/0010-0277(95)00687-7.

Grodner, D. and E. Gibson. 2005. Consequences

of the serial nature of linguistic input for

sentential complexity. Cognitive Science 29(2):

261290.

Hale, J. 2006. Uncertainty about the rest of the

sentence. Cognitive Science 30(4): 643672.

doi:10.1207/s15516709cog0000_64.

Hsiao, Y. and M. C. MacDonald. 2013. Experience and generalization in a connectionist

model of Mandarin Chinese relative clause

processing. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 767. doi:

10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00767.

Hudson, R. 1996. The difficulty of (so-called)

self-embedded structures. In P. Backley and

J. Harris (eds.), UCL Working Papers in

Linguistics 8: 283314.

Jaeger, T. F. 2013. Production preferences cannot

be understood without reference to

communication. Frontiers in Language Sciences

4: 230. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00230.

Kimball, J. 1973. Seven principles of surface

structure parsing in natural language.

Cognition 2(1): 1547.

Lany, J. and J. R. Saffran. 2011. Interactions

between statistical and semantic information

in infant language development.

Developmental Science 14(5): 12071219.

doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01073.x.

Levy, R. 2008. Expectation-based syntactic

comprehension. Cognition 106(3): 11261177.

doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.05.006.

Lin, C. J. C. 2008. The processing foundation of

head-final relative clauses. Language and

Linguistics 9(4): 813838.

MacDonald, M. C. 1999. Distributional

information in language comprehension,

production, and acquisition: Three puzzles

and a moral. In B. MacWhinney (ed.), The

Emergence of Language, pp. 177196. Mahwah,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

MacDonald, M. C. 2013a. How language

production shapes language form and

comprehension. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 226.

doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00226.

MacDonald, M. C. 2013b. Production is at the

left edge of the PDC but still central:

Response to commentaries. Frontiers in

Psychology 4: 227. doi:10.3389/

fpsyg.2013.00227.

MacDonald, M. C. and M. H. Christiansen. 2002.

Reassessing working memory: Comment on

Just and Carpenter (1992) and Waters and

Caplan (1996). Psychological Review 109(1):

3554; discussion 5574.

MacDonald, M. C., N. J. Pearlmutter, and M. S.

Seidenberg. 1994. The lexical nature of

syntactic ambiguity resolution. Psychological

Review 101: 676703.

MacDonald, M. C. and M. S. Seidenberg. 2006.

Constraint satisfaction accounts of lexical and

sentence comprehension. In M. J. Traxler and

M. A. Gernsbacher (eds.), Handbook of

Psycholinguistics, 2nd ed., pp. 581611.

Amsterdam: Elsevier.

MacDonald, M. C, and R. Thornton. 2009. When

language comprehension reflects production

constraints: Resolving ambiguities with the

help of past experience. Memory and Cognition

37(8): 11771186. doi:10.3758/MC.37.8.1177.

The Emergence of Language Comprehension

MacWhinney, B. 1977. Starting points. Language

53: 152168.

MacWhinney B. (ed.) 1999. The Emergence of

Language. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

McDonald, J. L., K. Bock, and M. H. Kelly. 1993.

Word and world order: Semantic,

phonological, and metrical determinants of

serial position. Cognitive Psychology 25(2):

188230. doi:10.1006/cogp.1993.1005.

Miller, G. A. 1956. The magical number seven,

plus or minus two: Some limits on our

capacity for processing information.

Psychological Review 63(2): 8197.

doi:10.1037/h0043158.

Miller, G. A. and N. Chomsky. 1963. Finitary

models of language users. In R. D. Luce, R. R.

Bush, and E. Galanter (eds.), Handbook of

Mathematical Psychology, vol. 2, pp. 419491.

New York: Wiley.

Mitchell, D. C. and M. Brysbaert. 1998.

Challenges to recent theories of

cross-linguistic differences in parsing:

Evidence from Dutch. In D. Hillert (ed.),

Sentence Processing: A Crosslinguistic

Perspective, pp. 313335. San Diego, CA:

Academic Press.

Montag, J. L. and M. C. MacDonald. 2009. Word

order doesnt matter: Relative clause

production in English and Japanese. In N. A.

Taatgen and H. van Rijn (eds.), Proceedings of

the Thirty-First Annual Conference of the

Cognitive Science Society, pp. 25942599.

Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society.

Newmeyer, F. J. 1998. Language Form and

Language Function. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

OGrady, W. 2011. Relative clauses: Processing

and acquisition. In E. Kidd (ed.), The

Acquisition of Relative Clauses: Processing,

Typology and Function, pp. 1338. Amsterdam:

John Benjamins.

Pickering, M. J. and V. S. Ferreira. 2008.

Structural priming: A critical review.

Psychological Bulletin 134(3): 427459.

doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.427.

Postle, B. R. 2006. Working memory as an

emergent property of the mind and brain.

Neuroscience 139(1): 2338.

doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.005.

Ramscar, M. and H. Baayen. 2013. Production,

comprehension, and synthesis: A

communicative perspective on language.

Frontiers in Language Sciences 4: 233.

doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00233.

99

Reali, F. and M. H. Christiansen. 2007. Word

chunk frequencies affect the processing

of pronominal object-relative clauses.

Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology

60(2): 161170. doi:10.1080

/17470210600971469.

Roth, F. P. 1984. Accelerating language learning

in young children. Journal of Child Language

11(1): 89107. doi:10.1017/S0305000900005602.

Smith, M. and L. Wheeldon. 2004. Horizontal

information flow in spoken sentence

production. Journal of Experimental Psychology:

Learning, Memory, and Cognition 30(3):

675686.

Sturt, P., F. Costa, V. Lombardo, and P. Frasconi.

2003. Learning first-pass structural attachment

preferences with dynamic grammars and

recursive neural networks. Cognition 88(2):

133169. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(03)

00026-X.

Tanaka, M. N., H. P. Branigan, J. F. McLean, and

M. J. Pickering. 2011. Conceptual influences

on word order and voice in sentence

production: Evidence from Japanese. Journal of

Memory and Language 65(3): 318330.

doi:10.1016/j.jml.2011.04.009.

Tanenhaus, M. K. and J. C. Trueswell. 1995.

Sentence comprehension. In J. L. Miller and

P. D. Eimas (eds.), Handbook of Perception and

Cognition. Volume 11: Speech Language and

communication, pp. 217262. San Diego, CA:

Academic Press.

Thornton, R., M. C. MacDonald, and M. Gil.

1999. Pragmatic constraint on the

interpretation of complex noun phrases in

Spanish and English. Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 25:

13471365.

Traxler, M. J., R. K. Morris, and R. E. Seely. 2002.

Processing subject and object relative clauses:

Evidence from eye movements. Journal of

Memory and Language 47(1): 6990.

doi:10.1006/jmla.2001.2836.

Wanner, E. and M. Maratsos. 1978. An ATN

approach to comprehension. In M. Halle,

J. Bresnan, and G. A. Miller (eds.), Linguistic

Theory and Psychological Reality, pp. 119161.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wells, J. B., M. H. Christiansen, D. S. Race, D. J.

Acheson, and M. C. MacDonald. 2009.

Experience and sentence processing:

Statistical learning and relative clause

comprehension. Cognitive Psychology 58(2):

250271. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2008.08.002.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Which is more accurate: Consecutive or simultaneous interpretingDocument13 pagesWhich is more accurate: Consecutive or simultaneous interpretingcarlosPas encore d'évaluation

- Skehan Modelsof Speakingandthe Assessmentof Second Language ProficiencyDocument24 pagesSkehan Modelsof Speakingandthe Assessmentof Second Language Proficiencyesra topuzPas encore d'évaluation

- Stockholm University: Department of EnglishDocument31 pagesStockholm University: Department of EnglishDr-Mushtaq AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Boers (2013) Cognitive Linguistic Approaches To Teaching Vocabulary Assessment and IntegrationDocument18 pagesBoers (2013) Cognitive Linguistic Approaches To Teaching Vocabulary Assessment and IntegrationEdward FungPas encore d'évaluation

- Skehan Nurturing NoticingDocument23 pagesSkehan Nurturing NoticingAmir SarabadaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Production and Speech Error: ObjectivesDocument12 pagesLanguage Production and Speech Error: ObjectivesPriyansh GoyalPas encore d'évaluation

- Model of Speech Production Planning - Shattuck-Hufnagel2019Document13 pagesModel of Speech Production Planning - Shattuck-Hufnagel2019Eduardo Flores GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice Effects On Speech Production Planning: Evidence From Slips of The Tongue in Spontaneous vs. Preplanned Speech in JapaneseDocument28 pagesPractice Effects On Speech Production Planning: Evidence From Slips of The Tongue in Spontaneous vs. Preplanned Speech in JapaneseBeth KongPas encore d'évaluation

- Sentence ProcessingDocument20 pagesSentence ProcessingAlfeo OriginalPas encore d'évaluation

- Bai MoiDocument9 pagesBai Moimunhi1602Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Influence of Task Structure and Processing Conditions On Narrative RetellingsDocument28 pagesThe Influence of Task Structure and Processing Conditions On Narrative RetellingsThangPas encore d'évaluation

- (2010) Formulaic Language and Second Language Speech Fluency - Background, Evidence and Classroom Applications-Continuum (2010)Document249 pages(2010) Formulaic Language and Second Language Speech Fluency - Background, Evidence and Classroom Applications-Continuum (2010)Như Đặng QuếPas encore d'évaluation

- Word Formation in Business NewsDocument8 pagesWord Formation in Business NewsJumi PermatasyariPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentasi PsycholinguisticsDocument13 pagesPresentasi PsycholinguisticsRupianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Execution of Speech PlanDocument7 pagesExecution of Speech PlanMUHAMMAD ARROFIQ SAPUTRAPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.1 Definition of Speaking: Review of Related LiteratureDocument20 pages2.1 Definition of Speaking: Review of Related LiteratureKhairil AnwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Fluency in Second Language AssessmentDocument17 pagesFluency in Second Language AssessmentAndréa EscobarPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive Linguistic Approaches to Teaching VocabularyDocument17 pagesCognitive Linguistic Approaches to Teaching VocabularyZaro YamatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Abrams - The Effect of Synchronous and A SynchronousDocument26 pagesAbrams - The Effect of Synchronous and A SynchronouswaxpoeticgPas encore d'évaluation

- An Over View of Formulaic Language and Its Possible Role in L2 Fluency DevelopmentDocument12 pagesAn Over View of Formulaic Language and Its Possible Role in L2 Fluency DevelopmentKrystian NawaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Frequency-Based Measures of Formulaic LanguageDocument3 pagesFrequency-Based Measures of Formulaic LanguageThangPas encore d'évaluation

- When Is It Appropriate To Talk Managing Overlapping Talk in Multi Participant Voice Based Chat RoomsDocument13 pagesWhen Is It Appropriate To Talk Managing Overlapping Talk in Multi Participant Voice Based Chat RoomsFatma Şeyma KoçPas encore d'évaluation

- Williams and Locatt 2003 - Phonolo G Ical Memory and Rule LearningDocument55 pagesWilliams and Locatt 2003 - Phonolo G Ical Memory and Rule LearningLaura CannellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Word Sense Disambiguation - FINAL by Workineh Tesema GudisaDocument21 pagesWord Sense Disambiguation - FINAL by Workineh Tesema GudisasenaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Foreigner Fyp - Speech Error From Cognitive Science PerspectiveDocument20 pagesForeigner Fyp - Speech Error From Cognitive Science Perspectiveahfonggg928Pas encore d'évaluation

- How Language Is ProducedDocument9 pagesHow Language Is ProducedPitri KarismandaPas encore d'évaluation

- IntelligibilityDocument53 pagesIntelligibilityMaria Laura MorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Process of Speech ComprehensionDocument5 pagesThe Process of Speech ComprehensionAnisa Safitri100% (1)

- Planning: Speech: Levelt's Model of L1 ProductionDocument22 pagesPlanning: Speech: Levelt's Model of L1 Productionkawtar oulahcenPas encore d'évaluation

- Execution of Speech PlanDocument8 pagesExecution of Speech PlanNur Chaulani YunusPas encore d'évaluation

- Springer Journal of Philosophical Logic: This Content Downloaded From 129.130.252.222 On Mon, 08 Aug 2016 09:12:16 UTCDocument27 pagesSpringer Journal of Philosophical Logic: This Content Downloaded From 129.130.252.222 On Mon, 08 Aug 2016 09:12:16 UTCGuido PalacinPas encore d'évaluation

- Nonliteral Language Processing and Methodological ConsiderationsDocument52 pagesNonliteral Language Processing and Methodological ConsiderationsNatalia MoskvinaPas encore d'évaluation

- O'Grady 2011 Language Acquisition Without An Acquisition DeviceDocument15 pagesO'Grady 2011 Language Acquisition Without An Acquisition DevicehooriePas encore d'évaluation

- (2nd Group) PSYCHOLINGUISTICDocument2 pages(2nd Group) PSYCHOLINGUISTICsarfian0% (1)

- Q2 Oral Comm. Week 2Document12 pagesQ2 Oral Comm. Week 2Jennie KimPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Lexicon2011Document34 pagesMental Lexicon2011Fernando lemos bernardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ma Lin Do 08 Word NetDocument6 pagesMa Lin Do 08 Word NetFreedom PikoPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory of Automaticity by MoorDocument22 pagesTheory of Automaticity by Moorteguh sawalmanPas encore d'évaluation

- TFG4Document5 pagesTFG4Inma PoloPas encore d'évaluation