Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Jason - Texture, Text and Context Vs Indexing

Transféré par

Marina MladenovićTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Jason - Texture, Text and Context Vs Indexing

Transféré par

Marina MladenovićDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Heda Jason

Texture, Text, and Context of the Folklore Text vs. Indexing

O f alt possible aspects of ordering and classifying oral and folk literaiure, I

have chosen to discuss here the relations betvveen indexing and the investi*

gadon of context(s). In recent decades, in folkloric parlance, context" has

bcen narrowed down to performance, i.e., to the most immediate and

simple social and theatricai aspects that are most readily and easilv observable and describable (Dundes 1964; Fine 1984). However, there are other

kinds of contcxt that are much morc important for thc shaping o f works of

oral and folk literature, for their significance in society, and for their

significance for individuals. The invesdgadon of these olher contcxts can

sub$tandally benefit from putung thc tcxts into some kind of ordcr, and

many quesuons can be answered only on the basis o f a body of well*ordered

texts. By anatyzing works in terms o f moufs, cpisodcs, typcs, and genres and

their texture in terms of formulae and figures o f speech and by ordering

these into meaningful groups and semandc fields, the invesugator prepares

the material for many and variegated quesuons. A series of contexts for

work$ of orai and folk literature will be briefly sketched and their reladons lo

ordering on various levels oudined.

1) Language. The dialect(s) used by a perform er/author (or group of

performers) to perform/compose the works forms its linguisdc context.

The invesdgauon of the language and of its dialects is the domain of

linguisdcs proper and not of folklorisucs, but the results of linguisdc invesugadon have to be considered as a basis from which the folklorist's invesugauon begins. The semandc aspcct of the vocabulary and the ordering o f the

vocabulary into semanuc fields are of paramount importance when cultural

and social signiflcance, meanings, and funcdons arc invcsugaied.

2) Sound. Any vocat pcrformance carries somc musical component, evcn if

not sung. (We are not concemed here with instrumental music but with the

musical component o f a performed text.) The aspect of sound also relates

to the wording of a recited work (i.e., a work not sung, be it couched in prose

or verse) insofar as intonadon may determine meanings in the text. Sentcncc structure and melody are closely connected and shape the prosody of

a work (see below, secdon 4.1).

Journal o f Folklort R tuarth. Vol. S4. No. S. 1997

Copyright C 1997 by ihe FolkJore Im titute. Indiana Umvenlty

222

Ilea Jason

While ihe musica! component of sung texts has received much scholarly

attention, very litUe research has been done on the sound component of

recited texts. The musical culture of the society forms the sound context for

both sung and recited works o f oral literaturc. Investigation of this musical

culturc is the responsibi!ity of musicologists (ethnomusicoiogists), and the

investigator of oral literature will build on thc results received from the

musicologist (classiftcations and othenvise).

3) Kinetics. Any work performed in view of an audience indudcs a kinetic

component which is the third aspect of the oral teKt, after the wording and

sound components. Movement i$ the subject of a special field of inquiry;

$ystematic descriptions and classification schemes for movement in a culture have not been made as yet (comparable to descriptions of music, for

example). Such descriptions and schcmes would help put the performance

into its contcxt.

4) Literary-artistic qualitie$. The two basic levels of the work are the texts

texture organized by the prosody and the content organized into logical

forms and content patterns.

4.1) Texture. The metric organization of the works wording into verscs,

alliteration, and rhymes; its formulae; and thc figurative language of poetic

images used have bcen much investigated. Both organizc the contcxt for

handv use by the performer-improvisor.

No index of formulae has been made to date (of any ethnopoetic genre),

and no invcstigation has come to the authors attcntion that would scarch

for those parts of thc content that are organized into formulac (semantic

fields). Both kinds o f investigations would put the individua! formula into

the wider context of its literature and culture. Recently the first index of

similcs has been compiled with thc prospect o f organizing the two parts of

similcs into scmantic fields and thus has put the individual simile into its

literary and cultural context (Selivanov 1990, done for Russian epics and

ballads; it is a pity that texts from several genres have been mixed and thus

the picture is not clear).

4.2) Content. Contem has been most elaborately investigated and ordered.

A. Aarnc (1910) bascd his typc$ for narrative and qua$i-narrativc genres on

content, while Wienert (1925) based his Sinntypen for parables on the idea

that the content expre$ses. For the non-narrative genre of proverbs,

Permjakov has established a scheme of logical types based on the logicat

form of thc argument in the proverb (see Permjakov 1968 and Kapits

1983).

All threea content type, a Sinntypc, and a logico-thematical typebring

a singlc text into the immediate litcrary context o f its variants (a serics of

variants forming a primary Iiterary context) and into the wider contexts of

its genre (or sub-genre) and o f the rcpertoirc o f thc rcspcctivc social unit

(see below, point 7).

T exture, T f.xt, and C ontext of the Folklore T ext vs. Indexing

223

The scheme of types for a genre orders the genre$ pool of contems for

various purposes. It should be kept >n mind that the meanings and

significances of works of oral and folk literature are encoded in their

content (and not in their form!). Among thc uses of an index is thc

systematic investigation o f the development in history of a culiure-society's

oral and folk literature. This is achievcd on thc basis o f a series o f descriptions of $ynchronic cross<uts of a genres repertoire in a culture*society (or

of the societys whole repertoiresee be!ow, point 6). Diverse cultures can

be systematically compared, mutual relations of oral and written traditions

and of high" and folk" literatures in a spedfic culture can be systematically

investigatcd, and so on (the emphasis hcre being on "systematically").

Investigation of mcanings has to be bascd on exact and systematic data

about content, and this data can be obtained only from well-made indices

focused on various levels: poetic images, formulae, motifs, episodes, content

types, idea-types, logical forms, genres, etc.

5) LiUrary~historical eonttxts. The whole literary repertoire, past and present,

of a culture, its whole oral and written tradition, its whole folk and high,

religious and secular literature, etc., form the most important contcxt for

the oral and folk literature of a given $ociety at a given moment in hi$tory.

Let us add that, of course, neighboring cultures (in space and time) also

form an important context. Without orderly indiccs of all levels of significancc, no systematic invcstigations of the rclations of a givcn body of

litcrature to its literary context are possiblc (investigaiions such as historical

development of literaturc, mutual influences, contacts in space and time,

Tife" of a theme, etc.).

6) Cultural conUxts. In addition to literature (and language, sound, and

movement of which oral literature is composed), culturc consists of many

more elements. All of these form contexts to literature, be it oral or written,

"folk" or high. Among these are, in order of importance for litcraturc,

bclicfs (of the official religion and otherwise), knowledge of all sorts (scientiflc/tcchnical, philosophical), and ideologies; visual arts, music, and dance;

and material culture. The relations of literature to all these as they havc

cxisted in the past and do exist in the investigated present should bc

handled in the motif index, which organizes thc content of literary work$

into scmantic fields and puts thcsc at thc disposal of thc invcstigator.

7) Soeial and psyehologicat conUxts.

7.1) Tht performer. Thc work livcs in the consciousncss of thc performcr as

an individual (a psychological aspect) and as a memt>er ofsocial groupings

on various lcvcls of complexity (a sociological aspect). Most of thesc groupngs form the audience." All pcrformers of a village or a district can bc said

to form a group, with common characteristics. Some genres are performed

in a sitting by a single individual performer; other genres in the same $ociety

224

Heda Jasort

may be performed as a production of a group of people (each piaying a

differeni pari in the production).

7.2) The audience. The audience of a performer in a single performance

may be thc fellow villagers/tribesmen of the performer, or a chance group

of people for an itinerant performer-visitor. The audience may also be

permanent, i.e., the performers villagers/tribesmen who are largely con*

stant throughout life. The oral artist's performance is socially meaningful

only in the framework of the audience. The audience-community i$ again

divisible into age, sex, professional, and class groupings; each of these can at

times function as a closed audiencc for certain groups of works. Thesc two,

the performcr(s) and the audience, are primary social actors who can bc

readily and empirically observed. Their behavior and interaction are the

uppermost level of the oral*literary work, open to immediate observation

and most easily recorded and described.

More complex groupings are secondary: they are theoretical and not

observable. They have to be consiructed by the investigator on the basis of

observable data in primary performance-audience groups, i.e., thcir investi*

gation needs much more sophisticated scholarly tools. Such secondary

groupings include ethno-religious, generational, gcnder, professionai, and

class groupings, the members of which exceed the local community. These

may be scattercd in spacc and time throughout the overall $ociety; a whole

culture-society (e.g., a nation) which is ethnically homogenous; and a

cultural area including both many ethnically homogenous culture-societies

and scattered groupings of the kinds mentioned above (consider, for in*

stance, the Muslim cultural area with its many ethnoreligious nations and

groups).

7.3) Social organizadon. A third factor impinging very much on oral and

folk literature is a societys organization and institutions. Ufe flow$ in the

framework of social organizations and institutions, and literature is part of

iifes activity. Let us mention, for example, popular religious literature

produced by religious instilutions, religious preaching that entcrs directly

into oral tradition, the culdvation of oral literature at medieval courts, oralliterary works that are obligatory parts of rituals and customs, and the

meddling into the flow of oral literature by political agents using it for

propaganda purposes. All of these change meanings and messages by

changing the pool of contents, its symbolic meanings, and the combinauons

simpler units enter into to form more complcx compositions.

Each social unit, from the individual performer to a wholc sociecy, has a

repertoire of works built from a pool of contents, combined with the help of

a set of certain composidon rules into works o f various gcnres. A mouf index

describes thc pool of contents and orders it into semandc fields; the type

index (or index of logical forms) orders and describes wholc works; and thc

gcnre indcx dcscribcs thc composidon of the repertoire. Indices of formu*

T exture. Text, and C ontext o f the Folklore T ext vs . 1ndexinc

225

lae and of figures of speech should describe and order the poetic means that

shape the texture of works. Thus, on every level indexing is a ncccssary

prerequisite to research. For a list of indices for motif, type, and genre up to

1992, see the second volume ofjason (forthcoming).

Jemsalem

REFERENCES CITED

Aame, Antti

1910 Vmeichnis der Marchentypen. FF Communications No. 3. Helsinki:

Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia Toimituksia.

Dundes, Alan

1964 *Texture, Text and Context." Southem Folklore Quarteriy 20:251-65.

Finc, Elisabeth C.

1984 TheFolklore Text. Bloomington: Iniana University Press.

Jason, Heda

(forthcomingJiVfo/i/, Typeand Genre. Vo). 1: A Manual for Compilation of Indices.

Vol. 2: Bibliography of Indices and Indexing. FF Communications.

Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatcmia Toimituksia.

Kapiis, Gcorgi I_

1983 Somaiijskieposlovid ipogovorhi. Moscow: Nauka.

Pcrmjakov, Grigorii L.

1968 hbrannyeposlovici i pogovorki narodov Vostoka. Moscovv: Nauka.

Selivanov, Fedor M.

1990 Hssdoiestvennye sravnenija msskogo pesennogo eposa: Sistematieskij ukazalel'.

Moscow: Nauka.

VVienert, Waltcr

1925 Die Typen der griechisch-romischen Fabel. FF Communications No. 56. Hcl*

sinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia Toimituksia.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Bloomfield Lecture For StudentsDocument4 pagesBloomfield Lecture For StudentsNouar AzzeddinePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter I Language, Culture, and SocietyDocument8 pagesChapter I Language, Culture, and SocietyJenelyn CaluyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cultural LinguisticsDocument29 pagesCultural LinguisticsMargaret PhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative - Typological Investigation of Nouns inDocument59 pagesComparative - Typological Investigation of Nouns inMirlan Chekirov100% (1)

- Language contact and linguistic changeDocument18 pagesLanguage contact and linguistic changeToto RodríguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Fillmore - 1968 - The Case For CaseDocument136 pagesFillmore - 1968 - The Case For CaseProfesseur MarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Verbal Hygiene by D CameronDocument2 pagesVerbal Hygiene by D CameronNandini1008Pas encore d'évaluation

- Towards A Theory of Language Policy: Bernard SpolskyDocument8 pagesTowards A Theory of Language Policy: Bernard SpolskyJurica PuljizPas encore d'évaluation

- Sociolinguistics: "Society On Language" "Language Effects On Society"Document3 pagesSociolinguistics: "Society On Language" "Language Effects On Society"Bonjovi HajanPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Concepts in LinguisticsDocument64 pagesBasic Concepts in LinguisticsJovie Oyando100% (1)

- LANGUAGE ECOLOGY AND DIVERSITY THREATSDocument19 pagesLANGUAGE ECOLOGY AND DIVERSITY THREATSElviraPas encore d'évaluation

- Oral communication norms and strategiesDocument7 pagesOral communication norms and strategiesBlancaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Speech CommunityDocument4 pagesThe Speech CommunityPyare LalPas encore d'évaluation

- DialectDocument7 pagesDialectBryant AstaPas encore d'évaluation

- VARIETIES OF ENGLISHDocument28 pagesVARIETIES OF ENGLISHStella Ramirez-brownPas encore d'évaluation

- Linguistic AreaDocument16 pagesLinguistic AreaEASSAPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Across Languages - Volume 1 Di Hellinger e BusmannDocument344 pagesGender Across Languages - Volume 1 Di Hellinger e BusmannManfredi Tuttoilmondo100% (1)

- Interface Between Morphology and Syntax in Garífuna Sentence StructuresDocument10 pagesInterface Between Morphology and Syntax in Garífuna Sentence StructuresAshreen Mirza100% (1)

- Sociolinguistics in Language TeachingDocument101 pagesSociolinguistics in Language TeachingNurkholish UmarPas encore d'évaluation

- Noam-chomsky-The Cartography of Syntactic StructuresDocument17 pagesNoam-chomsky-The Cartography of Syntactic StructuresnanokoolPas encore d'évaluation

- Underlying Representation of Generative Phonology and Indonesian PrefixesDocument50 pagesUnderlying Representation of Generative Phonology and Indonesian PrefixesJudith Mara AlmeidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Learn about the Hehe language spoken in TanzaniaDocument2 pagesLearn about the Hehe language spoken in TanzaniaAhmad EgiPas encore d'évaluation

- 1997 Lexical AffixesDocument16 pages1997 Lexical AffixesAnonymous Rapv5LS2J9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding the Relationship Between Language and SocietyDocument48 pagesUnderstanding the Relationship Between Language and Societydianto pwPas encore d'évaluation

- Beaugrande R., Discourse Analysis and Literary Theory 1993Document24 pagesBeaugrande R., Discourse Analysis and Literary Theory 1993James CarroPas encore d'évaluation

- Speech Community Under The Observing As Guided in The DefinitionsDocument4 pagesSpeech Community Under The Observing As Guided in The Definitionstariqahmed100% (1)

- Benveniste+ +Problems+in+General+LinguisticsDocument9 pagesBenveniste+ +Problems+in+General+LinguisticsEthan KoganPas encore d'évaluation

- Phonemes Distinctive Features Syllables Sapa6Document23 pagesPhonemes Distinctive Features Syllables Sapa6marianabotnaru26Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Belles-Lettes StyleDocument4 pagesThe Belles-Lettes StyleDiana TabuicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 39 Strategies For Text AnalysisDocument5 pagesTopic 39 Strategies For Text AnalysisMiriam Reinoso SánchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Tema 29Document33 pagesTema 29Leticia González ChimenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Study Guide PDFDocument4 pagesStudy Guide PDFRobert Icalla BumacasPas encore d'évaluation

- Siegel. Koine and KoineizationDocument12 pagesSiegel. Koine and KoineizationMónica Novoa100% (1)

- COUPLAND, N. Language, Situation, and The Relational Self - Theorizing Dialect-Style in SociolinguisticsDocument26 pagesCOUPLAND, N. Language, Situation, and The Relational Self - Theorizing Dialect-Style in SociolinguisticsMarcus GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Yang (2000) : "Internal and External Forces in Language Change"Document8 pagesYang (2000) : "Internal and External Forces in Language Change"phliPas encore d'évaluation

- Updated English LexicologyDocument179 pagesUpdated English LexicologyAziza QutbiddinovaPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Tenets of Structural LinguisticsDocument6 pagesBasic Tenets of Structural LinguisticsAlan LibertPas encore d'évaluation

- William Labov and The Social Stratification of RDocument3 pagesWilliam Labov and The Social Stratification of RSamaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Farris, C.S. - Gender and Grammar in Chinese With Implications For Language UniversalsDocument33 pagesFarris, C.S. - Gender and Grammar in Chinese With Implications For Language UniversalsmahiyagiPas encore d'évaluation

- Leonard BloomfieldDocument4 pagesLeonard BloomfieldArun AhujaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lehmann, Christian. Thoughts On GrammaticalizationDocument183 pagesLehmann, Christian. Thoughts On Grammaticalizationprinnn24100% (1)

- Topic 5Document9 pagesTopic 5Arian MarsinyachPas encore d'évaluation

- BS English-6th-ENGL3127-2 PDFDocument27 pagesBS English-6th-ENGL3127-2 PDFNational Services AcademyPas encore d'évaluation

- The syllable in generative phonologyDocument4 pagesThe syllable in generative phonologyAhmed S. MubarakPas encore d'évaluation

- Usage-Based Construction Grammar PDFDocument24 pagesUsage-Based Construction Grammar PDFBelenVettesePas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Literary Language, Genres and CriticismDocument32 pagesAnalysis of Literary Language, Genres and Criticismmiren48Pas encore d'évaluation

- Transformational-Generative Grammar: (Theoretical Linguistics)Document46 pagesTransformational-Generative Grammar: (Theoretical Linguistics)Les Sirc100% (1)

- Word Formation Processes in EnglishDocument12 pagesWord Formation Processes in EnglishFaisal Jahangeer100% (2)

- Power Point 1 MorphologyDocument12 pagesPower Point 1 MorphologyGilank WastelandPas encore d'évaluation

- History of SociolinguisticsDocument42 pagesHistory of SociolinguisticsTanveer Buzdar100% (1)

- HengeveldDocument100 pagesHengeveldmantisvPas encore d'évaluation

- 000 Euralex 2010 04 Plenary BOGAARDS Dictionaries and Second Language AcquisitionDocument25 pages000 Euralex 2010 04 Plenary BOGAARDS Dictionaries and Second Language AcquisitionIra PetrosyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Variation & Language VLCDocument18 pagesVariation & Language VLCAmirAli MojtahedPas encore d'évaluation

- Zeki Hamawand-The Semantics of English Negative Prefixes-Equinox Pub (2009) PDFDocument192 pagesZeki Hamawand-The Semantics of English Negative Prefixes-Equinox Pub (2009) PDFChibuzo Ajibola100% (1)

- Regional and Social Dialects Concept MapDocument2 pagesRegional and Social Dialects Concept MapMargarito EscalantePas encore d'évaluation

- KonglishDocument11 pagesKonglishIzzie ChuPas encore d'évaluation

- Makalah Language Society Bab 18 Kelompok 5Document8 pagesMakalah Language Society Bab 18 Kelompok 5Rizka Noviani Rahayu100% (1)

- File For LexicologyDocument202 pagesFile For LexicologyMiro BlackuPas encore d'évaluation

- Folklore: The Linguistics Aspect of Oral LiteratureDocument9 pagesFolklore: The Linguistics Aspect of Oral LiteratureArif WahidinPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical Poetics and Pragmatics of Slavic CharmsDocument26 pagesHistorical Poetics and Pragmatics of Slavic Charmsadu666Pas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Numskull Tales PDFDocument10 pagesIndian Numskull Tales PDFMarina MladenovićPas encore d'évaluation

- TekstoviDocument79 pagesTekstoviMarina MladenovićPas encore d'évaluation

- Repertoar Nova GodinaDocument87 pagesRepertoar Nova GodinaMarina MladenovićPas encore d'évaluation

- Burke History and FolkloreDocument8 pagesBurke History and FolkloreMarina MladenovićPas encore d'évaluation

- FFN 39 LowDocument28 pagesFFN 39 LowMarina MladenovićPas encore d'évaluation

- Zuppa IngleseDocument4 pagesZuppa IngleseMarina MladenovićPas encore d'évaluation

- Slovenian folklore and folklore studies at the turn of two millenniaDocument502 pagesSlovenian folklore and folklore studies at the turn of two millenniaNathaniel SotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading The Bible As Literature: Worksheet 4.1 On Literary GenresDocument5 pagesReading The Bible As Literature: Worksheet 4.1 On Literary GenresdarkinthekeysPas encore d'évaluation

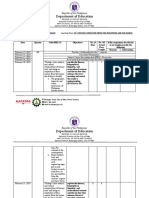

- MSAT-BOW-Template - Budget-of-Work-Matatag - Docx 21STDocument15 pagesMSAT-BOW-Template - Budget-of-Work-Matatag - Docx 21STmoanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Uptake and Localization of Dialogue Genres in the Popular Game Genshin ImpactDocument27 pagesUptake and Localization of Dialogue Genres in the Popular Game Genshin ImpactKalinda HoPas encore d'évaluation

- Roman Jakobson - The Functions of Language - Signo - Applied Semiotics TheoriesDocument7 pagesRoman Jakobson - The Functions of Language - Signo - Applied Semiotics Theorieswiandra, a.n.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cameroon Secondary Education Curriculum for English Language and Literature Form 1 & Form 2Document88 pagesCameroon Secondary Education Curriculum for English Language and Literature Form 1 & Form 2Epie Frankline100% (1)

- Study Guide for Drama TechniquesDocument7 pagesStudy Guide for Drama TechniquesEricho San Ignatius CuaresmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Magical Realism Mini UnitDocument28 pagesMagical Realism Mini Unitapi-239498423100% (3)

- Theory FaircloughDocument27 pagesTheory Faircloughngthxuan100% (1)

- Listen To The Herons WordsDocument195 pagesListen To The Herons Wordspatel_musicmsncomPas encore d'évaluation

- Democratic AestheticsDocument26 pagesDemocratic AestheticsAmadeo LaguensPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Literature Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesPhilippine Literature Lesson Plansordy mahusay mingasca100% (3)

- ALKON, Paul K. Origins of Futuristic FictionDocument166 pagesALKON, Paul K. Origins of Futuristic FictionDaniel Nikopol100% (3)

- DramaDocument8 pagesDramasyifa luthfiannisaPas encore d'évaluation

- Charlotte Pence Ed. The Poetics of American Song Lyrics PDFDocument309 pagesCharlotte Pence Ed. The Poetics of American Song Lyrics PDFaedicofidia67% (3)

- Creative Writing Learning ModuleDocument19 pagesCreative Writing Learning ModuleDaenerissePas encore d'évaluation

- GCE AL English Resouce BookDocument329 pagesGCE AL English Resouce BookMaliPas encore d'évaluation

- (Berg Film Genres) Catherine Driscoll-Teen Film. A Critical Introduction (Berg Film Genres) - Berg Publishers (2011)Document209 pages(Berg Film Genres) Catherine Driscoll-Teen Film. A Critical Introduction (Berg Film Genres) - Berg Publishers (2011)Sam Sam100% (3)

- A Reinvention of Realism in Raymond CarverDocument17 pagesA Reinvention of Realism in Raymond CarverrociogordonPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical Periods in Film StudiesDocument2 pagesHistorical Periods in Film StudiesFLAKUBELAPas encore d'évaluation

- BA in English ExamBlue PrintDocument14 pagesBA in English ExamBlue PrintshimelinigatuPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL CNF 22-23 W5Document3 pagesDLL CNF 22-23 W5Tyrone Webster PayadPas encore d'évaluation

- Myth of The Western - Carter, MatthewDocument257 pagesMyth of The Western - Carter, MatthewNathan Wagar100% (3)

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument8 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesNicole Azelea0% (1)

- 2012 Fendler LurkingDocument14 pages2012 Fendler LurkingPhung Ha ThanhPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviews: Fifth-Century Athens. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998. Pp. VIIIDocument23 pagesReviews: Fifth-Century Athens. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998. Pp. VIIIphilodemusPas encore d'évaluation

- Network Streaming Mandates Focus on Diverse Female StoriesDocument15 pagesNetwork Streaming Mandates Focus on Diverse Female StoriesjaimechsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Mil Week 5 8 Fact SheetsDocument19 pagesMil Week 5 8 Fact SheetsNIÑOYT channelPas encore d'évaluation

- Q1 Mod3 PDFDocument28 pagesQ1 Mod3 PDFmary rose89% (19)

- Trần Thị ThơDocument82 pagesTrần Thị ThơThu HuệPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary: I'm Glad My Mom Died: by Jennette McCurdy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: I'm Glad My Mom Died: by Jennette McCurdy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (2)

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipD'EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1135)

- Weapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingD'EverandWeapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (149)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1871)

- Make It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel - Book Summary: The Science of Successful LearningD'EverandMake It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel - Book Summary: The Science of Successful LearningÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (55)

- Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory SchoolingD'EverandDumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory SchoolingÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (494)

- The 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageD'EverandThe 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (72)

- Summary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (22)

- Learn Spanish While SleepingD'EverandLearn Spanish While SleepingÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (20)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- How to Improve English Speaking: How to Become a Confident and Fluent English SpeakerD'EverandHow to Improve English Speaking: How to Become a Confident and Fluent English SpeakerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (56)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (30)

- The Story of the World, Vol. 2 AudiobookD'EverandThe Story of the World, Vol. 2 AudiobookÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Follow The Leader: A Collection Of The Best Lectures On LeadershipD'EverandFollow The Leader: A Collection Of The Best Lectures On LeadershipÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (122)

- Functional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and MindD'EverandFunctional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and MindÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1)

- Learn Japanese While SleepingD'EverandLearn Japanese While SleepingÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)

- Financial Feminist: Overcome the Patriarchy's Bullsh*t to Master Your Money and Build a Life You LoveD'EverandFinancial Feminist: Overcome the Patriarchy's Bullsh*t to Master Your Money and Build a Life You LoveÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Summary: Greenlights: by Matthew McConaughey: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: Greenlights: by Matthew McConaughey: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (6)

- Summary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (15)

- Think Ahead: 7 Decisions You Can Make Today for the God-Honoring Life You Want TomorrowD'EverandThink Ahead: 7 Decisions You Can Make Today for the God-Honoring Life You Want TomorrowÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (7)

- Summary of The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business by Charles DuhiggD'EverandSummary of The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business by Charles DuhiggÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (261)

- Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to AchieveD'EverandLittle Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to AchieveÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (25)

- Taking Charge of ADHD: The Complete, Authoritative Guide for ParentsD'EverandTaking Charge of ADHD: The Complete, Authoritative Guide for ParentsÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (17)

- Growing Up Duggar: It's All About RelationshipsD'EverandGrowing Up Duggar: It's All About RelationshipsÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (37)

- Weapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingD'EverandWeapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (59)