Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci-2000-Journal of Gerontology - Psychological Sciences-P18-26

Transféré par

Noelle GatdulaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci-2000-Journal of Gerontology - Psychological Sciences-P18-26

Transféré par

Noelle GatdulaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Gerontology: PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCES

2000, Vol. 55B, No. I, P18-P26

Copyright 2000 b\ The Gerontological Swii'lv of America

Personality Traits and Suicidal Behavior and Ideation

in Depressed Inpatients 50 Years of Age and Older

Paul R. Duberstein, Yeates Conwell, Larry Seidlitz, Diane G. Denning, Christopher Cox, and Eric D. Caine

University of Rochester Medical Center, New York.

EPRESSIVE disorders in older adults are common

(Burvill, 1995; Lebowitz et al., 1997) and are associated

with increased all-cause mortality (Gallo, Rabins, Lyketos,

Tien, & Anthony, 1997; Penninx et al., 1999; Zubenko,

Mulsant, Sweet, Pasternak, & Tu, 1997). Completed suicide

may be the most preventable lethal complication. Although the

greatest number of suicides are committed by young adults, the

rate increases throughout the lifecourse and peaks in 80-84

year olds (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 1996, 1999).

Recognizing the public health impact of completed suicide on

individuals, families, and society, the United States Congress

passed resolutions in 1997 and 1998 declaring suicide prevention a national priority (Congressional Record, 1997, 1998).

The ultimate success of these resolutions will depend in part on

the identification of suicide risk factors and correlates. Research

aimed at identifying personality traits associated with suicidal

behavior can contribute to prevention efforts by defining groups

at high risk, before the development of a major depressive

episode or an acute suicidal crisis. The identification of highrisk groups is therefore a critical component of the contemporary prevention research agenda (National Institutes of Health,

1998). Using data collected on a sample of depressed inpatients

50 years of age and older, we report analyses designed to

determine the direction and strength of associations between the

personality traits that constitute the Five Factor Model of personality (Digman, 1990; John, 1990) and measures of suicidal

behavior.

The Five Factor Model (FFM) as a Hypothesis-Testing

and Hypothesis-Generating Tool

Based on decades of factor-analytic research on personality in

the natural lexicon and questionnaires, there is considerable

(Digman, 1990; John, 1990; McCrae & Costa, 1997), but not

complete (Cloninger, Svrakic, & Przybeck, 1993; Tellegen,

1985), agreement that personality attributes can be grouped

along five major dimensions: Neuroticism, Extraversion,

Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. Because this

P18

model of personality provides a relatively comprehensive coverage of personality traits, it can be used to explore and generate

hypotheses about phenomena that have been relatively underinvestigated or about which there is relatively little theorizing.

We are aware of no theory that makes explicit predictions

about the contributions of specific personality traits to specific

dimensions of suicidal behavior in particular demographic and

diagnostic groups. Most personality theories of suicidal behavior lack the specificity warranted by the epidemiological data.

For example, despite long-established age and gender differences in suicidal behavior (Durkheim, 1897/1951; Monk, 1987),

clinical writings (e.g., Buie & Maltsberger, 1989; Hendin, 1991)

have typically emphasized the role of hostility, independent of

age, gender, or any other demographic or contextual variable.

Use of an omnibus personality questionnaire grounded in the

FFM increases the likelihood that traits central to late-life suicidal behavior are not overlooked, even if they are ignored in clinical and theoretical writings. Indeed, the FFM may be construed

as hypothesis-generating. Proponents of the FFM argue that it

provides a fixed reference point from which to assess a variety

of different scales (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Marshall, Wortman,

Vickers, Kusulas, & Hervig, 1994). It therefore overcomes a

perennial problem in personality psychology: Scales with different labels measure the same trait, while those with the same

label measure different traits.

Among others, Kagan (1994), McAdams (1994), and Block

(1995) offer less optimistic opinions of the FFM. Kagan (1994)

critiques its basic premises, including the scientific utility of a

natural language approach to personality, self-report measures,

and factor-analysis itself. He ultimately concedes that, even

though the five factors "omit too much information" and are

"insufficiently differentiated... [they] do tell us something of

interest" (pp. 45-46). McAdams (1994) also takes issue with

the basic premises and criticizes trait assessments in general on

the grounds that they fail to provide causal explanations for

human behavior, disregard the conditional and contextual nature of human experience, and fail to provide enough detailed

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

Completed suicide may be the most preventable lethal complication of depressive disorders in older adults.

Identification of risk factors for suicidal behavior has therefore become a major public health priority. Using data collected on SI depressed patients 50 years of age and older, we report analyses designed to determine the associations between the personality traits that constitute the Five Factor Model of personality and measures of suicidal behavior and

ideation. We hypothesized that low Extraversion would be associated with a lifetime history of attempted suicide, and

high Neuroticism would be associated with suicidal ideation. Results were generally consistent with the hypotheses. We

also observed a relationship between Openness to Experience and suicidal ideation. These findings suggest that longstanding patterns of behaving, thinking, and feeling contribute to suicidal behavior and thoughts in older adults and

highlight the need to consider personality traits in crafting and targeting prevention strategies.

PERSONALITY AND SUICIDE

information to predict specific behaviors in certain circumstances. Block (1995) generally accepts the premises upon

which FFM research is based, though he is somewhat critical of

the "arbitrariness" (p. 189) of factor analysis and the overreliance on self- and peer-report data. He also raises a number

of technical concerns, such as the high intercorrelations among

the ostensibly uncorrelated five factors. Still, the FFM has withstood criticism from those who share, and do not share, its basic

assumptions (Costa & McCrae, 1995; McCrae & Costa, 1997),

and it has proven useful in research on health outcomes in older

adults (Hooker, Frazier, & Monahan, 1994; Hooker, Monahan,

Bowman, Frazier, & Shifren, 1998; Hooker, Monahan, Shifren,

& Hutchinson, 1992). Those achievements may be sufficient

justification for its continued application to questions of public

health significance pertaining to older adults.

Manton, 1986; Moscicki, 1989), but the risk of completed

suicide increases (CDC, 1999). Following the logic of the categorical model, we examined the direction and strength of associations between each of the personality traits that constitute the

FFM and specific variables related to (a) suicide attempts and

(b) suicidal ideation.

The Present Study: Overview and Hypotheses

The preceding sections point to the need for a study that

measures a range of personality traits and distinguishes among

putative categories of suicidal behavior. Data were collected on

psychiatric inpatients with major depressive disorder, 50 years of

age and older, about half of whom were men. This is a relatively

homogeneous group both diagnostically and demographically,

which should allay concern that relations between personality

and suicidal behavior may be attributable to major depression,

gender, or age.

We tested two hypotheses: (1) Suicide attempters are characterized by low Extraversion, and (2) Suicidal ideation is

associated with high Neuroticism. Extraversion refers to preferences for social interaction and the tendency to experience

positive emotion (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Low Extraversion

increases risk for suicide attempts in relatively younger samples (Beautrais, Joyce, & Mulder, 1999; Roy, 1998). Although

there have been some negative findings, low Extraversion has

been empirically associated with poor social support (Krause,

Liang, & Keith, 1990; Von Dras & Siegler, 1997) and the use

of irrational and socially avoidant problem-solving strategies

(Hooker et al., 1994), characteristics also associated with attempted suicide (Linehan, Chiles, Egan, Devine, & Laffaw,

1986). With respect to the second hypothesis, Neuroticism

refers to the disposition to experience negative affect, such as

sadness, anxiety, and self-consciousness. People who are high

in Neuroticism have a tendency to report more severe physical

(Costa & McCrae, 1987) and depressive (Lyness, Duberstein,

King, Cox, & Caine, 1998) symptoms, one of which is suicidal ideation. Given the paucity of previous research on personality and suicidal behavior in older adults and our interest in

generating novel hypotheses, it seemed premature to restrict

our analyses to Neuroticism and Extraversion. We therefore

explored the contributions of Openness, Agreeableness, and

Conscientiousness to late-life suicidal behavior. Including

these three variables in the regression analyses also ensured

more precise estimates of the effects of Neuroticism and

Extraversion.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were drawn from a larger, ongoing, case-control

study of attempted suicide in major depressive disorder.

Depressed inpatients 50 years of age and older who were

admitted to the hospital following a suicide attempt were compared with similarly depressed age- (5 years) and gendermatched inpatients whose admissions were not precipitated by

a suicide attempt. Although there is significant heterogeneity in

the prevalent diagnoses of young adult suicides, after age 50,

the psychiatric diagnoses associated with completed suicide become increasingly homogeneous, and affective disorders are

present in over 70% of cases (Conwell et al., 1996). Thus, by

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

Continua versus Categories?

It is generally believed that one must want to die in order to

think about killing oneself, just as one has to have some suicidal ideation before making a suicide attempt. And, of course,

one has to attempt in order to complete suicide. It is precisely

this sort of overlap among suicide constructs that has led to the

assumption that suicidal behavior can be conceptualized along

a severity continuum, with absence of death ideation at one end,

completed suicide on the other, and death ideation, suicidal

ideation, and attempted suicide in the middle. Similarly, it has

been assumed that people can be "more or less" suicidal. Thus,

it has been assumed that one's "suicidality" can be captured by

a single, composite, dimensional variable.

The notion of a severity continuum has intuitive appeal.

Completed suicide is undoubtedly a more severe form of suicidal behavior than suicidal ideation. However, researchers studying groups of suicide ideators, suicide attempters, and completed suicides may be examining categorically discrete

populations, each characterized by a discrete set of risk factors,

reflecting distinct underlying personality traits or constituent

cognitive, affective, and motivational processes.

The number and nature of distinct suicidal populations have

been debated for years (Linehan, 1986; Maris, 1992). This discussion must continue in order to identify and ultimately test

five of the most significant, yet implicit, assumptions in the

severity continuum model. These include the notions that (a) research on attempted suicide may be a proxy for research on

completed suicide; that is, conclusions about completed suicide

can be gleaned from studies of suicide attempters; (b) research

on suicidal ideation may substitute for research on attempted

suicide; (c) suicidal ideation is a clinical risk factor for attempted

suicide and completed suicide; (d) attempted suicide is a clinical

risk factor for completed suicide; and (e) the absence of reported

suicidal ideation indicates decreased risk of attempted or completed suicide in a given population or study group.

Whereas the severity continuum model implies shared demographic risk factors across the continuum, a categorical

model suggests that each putative category of suicidal behavior

may have specific risk factors. The demographic data are generally consistent with the categorical model. Rates of attempted

suicide are highest in young women (Kessler, Borges, &

Walters, 1999), but it is older men who are at greatest risk for

completed suicide (CDC, 1999). Similarly, rates of suicidal

ideation decrease throughout the lifecourse (Blazer, Bachar, &

P19

P20

DUBERSTE1NETAL.

choosing 50 as the lower age limit for study entry, we are able

to control for affective disorder without excluding a large portion of people at risk for completed suicide.

Materials

NEO-Pl-R.T\ie NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) is a

240-item measure of the five personality dimensions consistently identified in factor-analytic studies: Neuroticism,

Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and

Conscientiousness. An extensive literature supports its reliability and validity. Coefficient alphas for the five scales range from

.86 to .92 (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Longitudinal studies conducted over periods of up to 7 years have frequently reported

test-retest correlation coefficients greater than .6, attesting to

the stability of these five domains (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Although the 60-item NEO-FFI has been used in gerontology

research (e.g., Hooker et al., 1994) and in research on depressed

outpatients (Bagby et al., 1998), we are unaware of any study

that has used the 240-item NEO-PI-R with older, depressed

inpatients.

History and number of suicide attempts.For decades, the

standard approach to research on personality and attempted

suicide involved a static group comparison of individuals seeking health care following a suicide attempt with individuals

seeking care for another reason ("nonattempters"). This approach is limited primarily because a portion of those described as nonattempters have attempted suicide in the past. As

a general principle, when personality traits increase risk for

certain adverse health outcomes, such as attempted suicide,

risk refers to the entire lifecourse and is not confined to the period of time during which subjects are enrolled in a study.

Thus, in the present study we examined the relationship between personality and (a) lifetime suicide attempter status, and

(b) number of suicide attempts.

Our data on the number of suicide attempts were based, in

part, on participants' responses to the questions: "How many

times all together in your life have you actually done something

with the intention of taking your life?" and "How many suicide

attempts have you made in your life?" With respect to the latter

question, past self-destructive behaviors were coded as suicide

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

The study was conducted at four teaching hospitals in the

northeastern United States (Rochester, NY), including two

community hospitals, one tertiary care facility, and one academic medical center. Acknowledging that there are problems

inherent in any definition of "suicide attempt" (Beck &

Greenberg, 1971; O'Carroll et al., 1996), attempted suicide was

defined as an intentional self-destructive act; an expressed wish

to die was not necessary.

Recruitment procedures were as follows. Project coordinators screened the records of all patients 50 years of age and

older admitted to the four hospitals or seen in psychiatric consultation on the medical and surgical services following a suicide attempt. Because the amount and type of comorbidity were

important variables that may have distinguished groups, comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions were not exclusionary

criteria if the diagnosis of major depressive disorder was suspected. Following approval from the patient's attending physician, a member of the research team approached patients to

obtain their informed consent to be interviewed by one of the

project coordinators (all of whom have masters degrees), and to

complete self-report questionnaires. Psychiatric diagnoses were

made on the basis of an integration of all data sources according to DSM-TII-R criteria (American Psychiatric Association,

1987) in a consensus conference attended by members of the

research team. Potential participants were excluded if the laboratory work-up, physical examination findings, and the temporal relation of depressive symptoms to the course of associated

physical illness or substance exposure suggested that the patient's mood syndrome was etiologically related to a specific

medical condition or substance exposure. Of the 87 participants

who completed the NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEOPI-R), only 2 suicide attempters and 4 nonattempters were subsequently excluded because they met criteria for organic mood

disorder; 4 other suicide attempters and 1 nonattempter who

met criteria for that disorder did not complete the NEO-PI-R.

All participants (n = 81; 34 [42%1 men, 47 [58%] women)

who completed the NEO-PI-R and met inclusion criteria were

included in the analyses; 14 others completed the NEO-FFI (60

item short form; Costa & McCrae, 1992), and 50 (34.5%) refused or were unable to complete any personality inventory despite their participation in other phases of the research and our

assiduous efforts to increase the return rate. Participants in the

larger study from which these analyses were conducted were,

on average, about 6 years older, and scored nearly 2 points

lower on the Mini Mental State Exam (Folstein, Folstein, &

McHugh, 1975; M = 25.7, SD = 4.1; M = 27.5, SD = 2.5). The

sample was predominantly Caucasian ( = 78; 96.3%), with a

mean (SD) age of 61.3 (9.6) years. The age range was 50 to 87

years. Thirty-three (40.7%) participants were married, 21 (25.9

%) were separated/divorced, and 34 (42%) lived alone at the

time of admission. One-third of the sample (n = 27, 33.3%) was

employed, and slightly less than one-third (30.8%) was either

on disability (n = 14) or unemployed (n = 1 1 ) . Thirty-seven

(45.6%) were in the midst of their first episode of major depression. Slightly less than half (n - 40,49.4%) was diagnosed with

severe major depression (American Psychiatric Association,

1987); 27 cases were judged to be moderate, and 3 were mild.

Eleven patients (14.2%) had psychotic features. Slightly more

than half (n = 44; 54.4%) had at least one additional Axis I diagnosis. The most common comorbid Axis I diagnosis was alcohol or substance abuse or dependence in full remission (n = 21,

25.9%). Dysthymia was present in about 12% of the sample (n

= \ 0). Somatoform disorders (n = 8), active alcohol/substance

disorders (n 8), panic disorder ( = 7), and phobias (n = 7)

were each present in slightly less than 10% of the sample. Scores

on the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Beck, Weissman, Lester, &

Trexler, 1974) were elevated (M = 12.4, SD = 5.7), consistent

with scores obtained on an older, depressed outpatient sample

(Hill, Gallagher, Thompson, & Ishida, 1988). Thirty-four of the

81 (41.9%) participants were admitted to the study following a

suicide attempt; 20 of these participants had made previous attempts. Eleven of the 47 patients (13.6%) whose admissions

were not precipitated by a suicide attempt had previously attempted suicide. Excluding the suicide attempts that immediately preceded and precipitated hospitalization, dates of the most

recent previous suicide attempt ranged from less than 1 week to

more than 5 years prior to admission, with the majority occurring more than 2 years prior to admission.

PERSONALITY AND SUICIDE

attempts if participants labeled the behavior as a suicide attempt

even if they disavowed an expressed intention to die. Previous

psychiatric and medical charts were reviewed in an effort to

gather additional data on the number of suicide attempts.

Discrepancies between the number of self-reported suicide attempts and chart-documented suicide attempts were resolved

by recording the higher number documented or reported.

Spectrum of Suicidal Behavior Scale (SSB).Project coordinators used this 5-point ordinal scale (Pfeffer, Stokes, &

Shindledecker, 1991) to rate the participants' most serious suicidal behavior over the past month. Thus, the SSB and SSI

cover different time frames (month prior to hospitalization vs.

week prior to interview). Participants were rated a 1 (nonsuicidal) if there was "no evidence of any self-destructive or suicidal

thoughts or actions," a 2 if there is evidence of suicidal ideation,

a 3 if they made a suicidal threat, a 4 if they made a mild suicide attempt, or a 5 if they made a serious suicide attempt. In

the present study, the SSB served primarily as a measure of suicidal ideation in the month prior to admission. For analytic purposes, we therefore dichotomized SSB scores (1 vs. other) and

estimated its reliability by means of the kappa-coefficient (K =

.54) using chart documentation of preadmission suicidal behavior as the criterion.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R.This instrument was used to establish Axis I psychiatric diagnoses

(Spitzer, Williams, & Gibbons, 1987). In order to examine its

validity in this group of older inpatients with major depression,

some members of the research team assessed psychiatric inpatients while others independently interviewed family informants (n = 26 pairs). Kappa coefficients for the diagnoses of

any substance use disorder, affective disorder, and their comorbidity ranged from 0.61 to 0.75.

Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE).The MMSE measures

cognitive function (Folstein et al., 1975). Scores can range from

0 to 30. The MMSE score is not used as an inclusion criterion;

rather, it serves solely as a means of characterizing cognitive

function.

Analytic Plan and Overview of Presentation of Results

First, descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among study

variables are reported. Kendall's tau and t statistics are presented because many of the endpoints were binary or counts

with skewed distributions. Next, the results of a series of regression analyses are reported. Binary endpoints were analyzed by

multiple logistic regression. Goodness of fit was examined by

using the Hosmer-Lemeshow (1989) test. Continuous endpoints were analyzed by multiple linear regression analysis,

which included an examination of residuals as a check on the

required assumptions of normally distributed errors with constant variance. If the residual analysis indicated a violation of

assumptions, then the data were logarithmically transformed

and standardized to behave like normal deviates (Chatterjee &

Hadi, 1988). Cases with standardized residuals greater than 3 in

absolute value were excluded as outliers from the regression

analysis. Counts and endpoints with skewed distributions were

analyzed by Poisson regression (McCullagh & Nelder, 1989),

which also included an outlier analysis. Standardized residuals

are based on components of the Pearson chi-square statistic for

goodness of fit of the model. All analyses were adjusted for age

and gender. Predictors included age, gender, and each of the

five traits that constitute the FFM: Neuroticism, Extraversion,

Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. All reported p values are two-tailed.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations (Kendall's

tau) between the NEO factors and continuous outcomes (SSI

and number of suicide attempts) are presented in Table 1. There

were slight, downward trends with age in Neuroticism and

Openness. The SSI score was positively correlated with

Neuroticism. t tests were conducted to examine the unadjusted

relationships between the personality variables and dichotomous endpoints. Table 2 shows that women, suicide ideators,

and death ideators obtained higher Neuroticism scores, and

those who had attempted suicide obtained lower scores on

Extraversion. Of the 10 intercorrelations among the 5 NEO

variables, five had absolute values less than .07; the highest

value was .46. Therefore, multicollinearity did not appear to

pose any problems for the regression analyses.

Presence and Number of Suicide Attempts

The first logistic regression sought to determine whether the

personality variables were associated with having made a suicide attempt. As shown in Table 3, those who obtained lower

Extraversion scores were more likely to have made a lifetime

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

Scale of Suicidal Ideation (SSI).Two outcome measures

were extracted from this 19-item, observer-rated measure: (a)

presence of suicidal ideation and (b) presence of death ideation

(Beck, Kovacs, & Weissman, 1979). Questions pertained to the

week prior to the interview or the interval between the suicide

attempt and interview, whichever was shorter. Thus, for those

hospitalized following a suicide attempt, the SSI provides data

on the presence of suicidal and death ideation following a suicide attempt. The first three items concern the wish to live, the

wish to die, and the extent to which one wish outweighs the

other. The presence of death ideation was operationally denned

as a score of 1 or greater in response to these three items, meaning that the wish to die outweighed the wish to live. Items 4 and

5 concern thoughts of self-destruction, either by active (e.g.,

shoot yourself) or passive (e.g., not taking medicine that is

needed to survive, refusing to nourish oneself) means. The presence of suicidal ideation was operationally defined as an affirmative response to either Question 4 or Question 5. The final

14 questions, which concern the frequency, duration, and the

participant's attitude toward suicidal thoughts, were administered only to those who reported suicidal ideation in response

to Items 4 or 5. Participants obtain relatively high SSI scores if

they report that they "accept" the suicidal thoughts, have little

control over them, have little concern about family, religion, or

other potential deterrents to suicide, have thought extensively

about how to kill themselves, written suicide notes, or changed

wills or life insurance policies. Severity of suicidal ideation was

operationally defined as the total score on the SSI. The SSI has

established reliability and concurrent validity (Beck et al.,

1979). Coefficient alpha for the current study (ideators only)

was .91.

P21

P22

DUBERSTEIN ET AL.

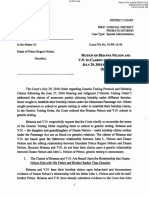

Table 1. Unadjusted Relationship Between NEO-PI and Continuous Variables: Kendall's Tau

Continuous Variable

SD

Ne

Ex

Op

Ag

Co

Age

Number of lifetime SA

Total SSI score

81

81

81

61.30

9.6

1.6

10.3

-.29***

.19*

2g***

.04

-.19*

-.15

-.17*

.04

.11

-.06

-.04

.07

-.15

-.04

-.14

0.85

7.52

Ne = Neuroticism; Ex = Extraversion; Op = Openness to Experience; Ag = Agreeableness; Co = Conscientiousness; SA= Suicide Attempts; SSI = Scale for

Suicidal Ideation.

*/><05. ***p< .001.

Table 2. Unadjusted Relationships Between NEO-PI and Dichotomous Variables: /-Statistics

Categorical Variable

Ne

Gender ( = 47 women, 34 men)

Ex

Lifetime SA (n = 45 yes, 36 no)

Suicidal ideation - SSB (n = 61 yes, 20 no)

Suicidal ideation - SSI (n = 32 yes, 49 no)

Death ideation - SSI (n = 53 yes, 28 no)

-0.15

2.66**

-2.03*

-1.50

3.11***

3.01***

-1.06

-1.24

Op

Co

Ag

0.85

-0.44

1.48

1.80

1.76

1.91

-1.77

0.14

-1.23

-1.21

-0.86

1.31

-1.60

-1.64

-0.69

Lifetime SA = participants with a lifetime history of at least one suicide attempt were contrasted with all others. Suicidal ideation - SSB = participants who scored

a 1 (absence of suicidal ideation or suicide attempt in the month prior to hospitalization) were contrasted with all others; Suicidal ideation - SSI = participants who

reported suicidal ideation in the week prior to interview (scored a 1 or higher on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation) were contrasted with all others; Death ideation - SSI

= participants who acknowledged that their wish to die outweighed their wish to live in the week prior to interview (scored a 1 or higher on the death ideation items

of the Scale for Suicidal Ideation) were contrasted with all others; Ne = Neuroticism; Ex = Extraversion; Op = Openness to Experience; Ag = Agreeableness: Co =

Conscientiousness. *p < .05; **p < .01 ;***/}< .001. All rf/s = 79, except where otherwise noted.

"Women scored higher than men.

h

Unequal variance (p < .05), there was greater heterogeneity among those with a lifetime SA; d/'tbr t-test = 78.

Table 3. Regression Results

Significant

Predicted Variable

Lifetime SA

Number of lifetime S A (outliers removed)

No suicidal ideas-SSB

Analysis

Model

1

2

3

Logistic

Poisson

Logistic

Predictor(s)

Coeff

SE

X:(D

p value

Extraversion

Extraversion

Openness

-.032

.016

-.026

-.054

+.038

.007

.025

4.43

14.06

.035

.0002

.02

.05

.01

.05

.02

Agreeableness

Suicidal ideation-SSI

Death ideation-SSI

4

5

Logistic

Logistic

Age

Openness

Neuroticism

-.087

.021

.038

+.038

+.037

.021

.018

5.65

3.73

6.38

3.87

4.49

Lifetime SA = participants with a lifetime history of at least one suicide attempt were contrasted with all others; Suicidal ideation - SSB = participants who scored

a 1 (absence of suicidal ideation or suicide attempt in the month prior to hospitalization) were contrasted with all others; Suicidal ideation - SSI = participants who

reported suicidal ideation in the week prior to interview (scored a 1 or higher on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation) were contrasted with all others; Death ideation - SSI

= participants who acknowledged that their wish to die outweighed their wish to live in the week prior to interview (scored a 1 or higher on the death ideation items

of the Scale for Suicidal Ideation) were contrasted with all others; CoetT = coefficient.

suicide attempt (Table 3, Analysis 1). The Hosmer-Lemeshow

goodness of fit was not significant, x2 (8) = 9.90, p = .27, indicating a satisfactory fit. Next, we examined predictors of the

number of previous suicide attempts using Poisson regression.

Higher Neuroticism and lower Extraversion emerged as significant predictors; however, 4 participants were outliers. In each

case, the predicted number of suicide attempts was lower than

the actual number. All 4 had at least two Axis I diagnoses; 3 of

the 4 had psychotic features. Concerned that the nature and interpretation of our findings may have been unduly influenced

by this relatively small group reporting numerous suicide attempts, we removed the outliers and conducted another Poisson

regression. The results (Table 3, Analysis 2) partially duplicated

the previous analysis. Again, Extraversion was a strong predictor, but Neuroticism was not, despite its significance in the pre-

vious analysis and its association with the number of lifetime

suicide attempts in the unadjusted analyses (Table 2). Next, we

conducted a Poisson regression to predict the number of suicide

attempts among those with a lifetime history of attempted suicide (n = 45; analyses not shown). No significant predictors

emerged, but there was a trend for those higher in Neuroticism

to make more attempts, x2 (1) = 3.17, p = .07.

Suicidal and Death Ideation

Two groups were constructed from the SSB data, those who

reported no suicidal ideation or behavior in the past month and

those who reported suicidal ideas or made a suicide attempt.

Table 3 (Analysis 3) shows that, in a logistic regression predicting absence of suicidal ideation, low Openness and high

Agreeableness emerged as significant predictors. This contrasts

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

1 .97'*

1 .69"

PERSONALITY AND SUICIDE

emerged as significant predictors of death ideation. The

Hosmer-Lemoshow for the overall model was nonsignificant,

X2 (8) = 8.33, p = .40, indicating a satisfactory fit.

DISCUSSION

These findings reinforce the notion that personality traits

ought to be seriously considered as potential risk factors for

late-life suicidal behavior and ideation. Even in this demographically and diagnostically homogenous group of psychiatric inpatients, personality traits were important predictors of

suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. Although there were

some negative findings, regression analyses supported hypothesized associations between Extraversion and attempted suicide

and between Neuroticism and suicidal ideation. These analyses

also generated a novel hypothesis linking Openness to suicidal

ideation.

Substantive Findings

Three findings are especially noteworthy. First, higher

Extraversion distinguishes people who have never made an attempt from those who have. Extraversion is positively associated with positive affect (Clark, Watson, & Mineka, 1994) and

increased social support (e.g., Von Dras & Siegler, 1997), and

negatively correlated with trait, but not state, hopelessness

(Young et ah, 1996). Extraverted individuals may be less likely

to engage in suicidal behavior even in the midst of a depressive

episode because they are more likely to recruit and affectively

benefit from friendships and family relations, perhaps as a result of better social skills (cf. Zweig & Hinrichsen, 1993).

Suicide attempts among those who are low in Extraversion may

reflect a tendency to take matters into one's own hands, rather

than attempt to recruit help from others. Strategies for treating

young adult suicide attempters (Linehan, 1993) have been informed by data linking personal concerns (Linehan et ah, 1986)

or personality dimensions (Rudd, Joiner, & Rajab, 1996) with

suicidal behavior, but similar data on older adults are rare.

Future research aimed at identifying the mediators of the relationship between Extraversion and attempter status may lead to

interventions designed to decrease the risk of nonfatal suicidal

behavior. This is important in part because suicide attempts

may exacerbate the physical morbidity (Gallo et ah, 1997; Katz,

1996 ) and mortality risks (Gallo et ah, 1997; Penninx et ah,

1999; Zubenko et ah, 1997) frequently associated with late-life

depressive disorders.

Although our findings are consistent with the notion that

Extraversion is associated with lifetime suicide attempter status,

it is possible that other personality traits (e.g., low Openness,

high Neuroticism) are associated with the lethality of attempts.

This idea could be examined in a study that includes a sufficient sample of individuals whose suicide attempts lead to severe medical complications.

Second, as hypothesized, Neuroticism is associated with suicidal ideation. However, whereas significant relationships

between Neuroticism and measures of suicidal ideation were

obtained in all three univariate analyses (SSB, SSI-Suicidal

Ideation, SSI-Death Ideation), the regression analyses told a

more complex story. Neuroticism was a strong predictor of SSIDeath Ideation in these analyses, but was not associated with

the other two suicide ideation variables. Thus, the associations

between Neuroticism and suicidal ideation in univariate analyses may be due in part to its associations with other traits, particularly Agreeableness and Openness.

Third, patients low in self-reported Openness are less likely to

report suicidal ideation. Perhaps patients low in Openness are

protected from suicidal ideation, and consistent with the severity

continuum model, they are less vulnerable to completed suicide.

However, we have previously reported that low informantreported Openness may be a risk factor for completed suicide

(Duberstein, Conwell, & Caine, 1994). How can this discrepancy be reconciled? Perhaps the apparently discrepant findings

can be ascribed to methodological differences. Self-reported

Openness and informant-reported Openness may not be comparable constructs in older, depressed persons. This is unlikely,

given the extensive literature supporting the relationship between

self- and informant-reported data (Costa & McCrae, 1992), even

in depressed outpatients (Bagby et ah, 1998). In our own sample

of 57 depressed inpatients 50 years of age and older, the relationship between self- and informant Openness (intraclass correlation coefficient = .49) was moderately strong. Acknowledging

that other methodological explanations may account for the apparently discrepant findings, substantive hypotheses must also be

entertained. People with major depression who are low in

Openness may be at increased risk for completed suicide precisely

because they are less likely to feel, or report feeling, suicidal. This

hypothesis represents a genuine challenge to the severity continuum model. Affective muting may be adaptive at earlier points in

the lifecourse, but could also increase risk for late-life completed

suicide (Clark, 1993; Duberstein, 1995). Further research on

Openness and suicidal behavior is warranted, given the obvious

implications for risk detection and prevention.

Limitations and Strengths

It cannot be assumed that the present findings generalize to

other diagnostic and demographic subgroups. Participants who

completed the NEO-PI-R were about 6 years younger and may

have had slightly better cognitive function than those who did

not complete the 240-item inventory. Nor can it be assumed

that these findings generalize to the small fraction of depressed

patients with organic mood disorder. The sample size is also

relatively small for personality research, so caution must be exercised, especially in interpreting negative findings. Finally, it

must be acknowledged that the results may have differed had

other age cutoffs been used as the lower limit of study entry

(e.g., 60 or 65).

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

with the unadjusted analyses, which showed a relationship between Neuroticism and the SSB score (Table 2). The HosmerLemeshow for the multiple regression was nonsignificant, \2

(8) = 10.75, p = .22, indicating a reasonable fit. When we dichotomized the SSI score (0 vs. > 0) and created two groups,

suicide ideators and nonideators, the logistic regression (Analysis 4) yielded one significant predictor (age), in contrast to the

unadjusted analyses, which implicated Neuroticism in suicidal

ideation (Table 2). We also conducted a linear regression with

the total score on the SSI as the dependent variable. Again, only

age was associated with that outcome, F(l,73) - 4.56,p = .04,

but there was a trend for those higher in Openness to obtain

higher SSI scores, F( 1,73) = 3.25, p = .07. Next, we created

two groups, those who reported death ideation in response to

Items 1-3 of the SSI and those who did not. Table 3 (Analysis

5) shows that higher Neuroticism and higher Openness

P23

P24

DUBERSTE1NETAL.

These limitations must be weighed against the study's

strengths, chief of which are its public health significance and

its foray into new territory. No previous study has applied a

comprehensive personality taxonomy to the study of late-life

suicidal behavior. Suicide is a major public health problem. By

attempting to identify putative risk factors for suicidal behavior,

social scientists can contribute to prevention efforts by defining

groups at high risk, before the development of an acute crisis.

This study represents a step in that direction. Other strengths of

the study include a well characterized and carefully diagnosed

sample at future risk for self-harm.

likely that suicide ideators, suicide attempters, and completed

suicides are categorically discrete groups, each characterized by

a discrete set of risk factors, reflecting distinct underlying personality and constituent cognitive, affective, and motivational

processes. Recognition of these differences may result in more

efficient prediction of attempted and completed suicide (Rudd

et al., 1996).

A promising approach to preventing suicide in older adults

involves screening for depression in primary care practices

(Unutzer, Katon, Sullivan, & Miranda, 1999). However, some

believe that the need for legalization of assisted suicide in certain contexts is as pressing a need as suicide prevention. This

dilemma is complicated by the absence of consensus regarding

the conceptualization, measurement, or treatment of psychological distress or psychiatric disorders in individuals with lifethreatening illnesses. Still, screening instruments have been

shown to have adequate sensitivity and specificity in predicting

major depression in older primary care patients (Lyness et al.,

1997). If carefully conducted preintervention research continues to implicate certain personality traits in late-life suicidal behavior, it may be desirable to screen for personality traits as

well. All screening and surveillance mechanisms should be

linked to systems capable of providing a range of interventions

and services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was financially supported in part by Public Heakh Service

Grants K07-MH01135, R03-MH55149, and RO1-MH51201. Nancy Talbot, Jill

Eichele, and anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on previous

drafts of the manuscript. We also wish to extend our appreciation to Andrea

DiGiorgio, Wendy Wyland, Jack Herrmann, Barbara Hughson, Megan

Cavanagh, and Tamson Kelly Noel for their assistance in data collection; to

Carrie Irvine for data management; and to Josephine Lauri and Marge Roberts

for manuscript preparation. An earlier version of this article was presented at

the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Chicago,

August 1997.

Address correspondence to Paul R. Duberstein, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Rochester Medical Center, 300 Crittenden Blvd., Rochester, NY

14642. E-mail: Paul_Duberstein@unnc.rochester.edu

REFERENCES

American Association of Retired Persons Foundation/Center for Mental Health

Services. (1997). Suicide prevention project: Final report summary. Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders (3rd ed.revised). Washington, DC: Author.

Bagby. R. M., Rector, N. A., Bindseil, K., Dickens, S. E., Levitan. R. D., &

Kennedy, S. H. (1998). Self-report ratings and informants' ratings of personalities of depressed outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155,

437-438.

Beautrais, A. E., Joyce, P. R., & Mulder, R. T. (1999). Personality traits and

cognitive styles as risk factors for serious suicide attempts among young

people. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 37^t7.

Beck, A. T., & Greenberg, R. (1971). The nosology of suicidal phenomena:

Past and future perspectives. Bulletin of Suicidology, 8, 10-17.

Beck, A. T, Kovacs. M., & Weissman, A. (1979). Assessment of suicidal

ideation: The scale for suicidal ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology. 47, 343-352.

Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Eester, D., & Trexler, L. D. (1974). The measure-

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that suicidal thoughts and behavior are

rooted in longstanding patterns of behaving, thinking, and feeling, and highlight the need to consider personality traits in crafting and targeting prevention strategies. Suicidal ideas and

behavior are not an inevitable consequence of aging, disease,

disability, or even depression. The current findings thus

challenge an ageist stereotype that has probably contributed

to a lack of interest in preventing late-life suicide (AARP

Foundation/Center for Mental Health Services, 1997). On the

other hand, findings must be regarded as preliminary. Several

lines of preintervention research ought to be pursued.

The "state-trait problem" potentially confounds research on

psychiatric inpatients, many of whom may be in acute distress

while completing questionnaires or participating in interviews.

Although it is unlikely that our observation that suicidal behavior and ideas are associated with Extraversion, Neuroticism,

and Openness, follow-up data, collected when patients no

longer meet diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder,

would be useful (e.g., Santor, Bagby, & Joffe, 1997). Future research may also benefit from informant reports and projective,

physiological, or other nonverbal sources of psychological

information.

By collecting data on a relatively homogeneous group of

older persons with major depression, we sought to decrease the

probability that potentially confounding effects of age or major

psychiatric diagnosis would obscure relationships between personality and suicide variables. Still, heterogeneity was apparent

in the analyses on previous suicide attempts. These analyses

suggested that Neuroticism may contribute to multiple suicide

attempts in those with comorbidity. Further research on larger

samples may be necessary to determine whether the personality

traits associated with suicidal behavior in depressed patients

with psychiatric comorbidity differ from those without comorbidity.

Even in the absence of consensus concerning the ideal design, sampling strategy, and statistical analysis required to determine whether the constructs of suicidal ideation, attempted

suicide, and completed suicide are categorically distinct (cf.

Flett, Vredenburg, & Krames, 1997; Meehl, 1992), tragedies

may be prevented for now simply by acknowledging that developing risk-identification and prevention strategies based on assumptions implicit in the severity continuum model could be

misguided. Variables associated with the absence of reported

suicidal ideation, such as low Openness, may not confer decreased risk for completed suicide. Paradoxically, in some

patients who are low in Openness, the absence of reported suicidal ideation may confer increased suicide risk.

This study uncovered the possibility that different personality variables are associated with attempted suicide and suicidal

ideation, with Extraversion associated with the former and

Openness more closely tied to the latter. We are not arguing for

eliminating the severity continuum model of suicide; rather, we

are suggesting that the categorical model has much to offer. It is

PERSONALITY AND SUICIDE

P25

ment of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 42, 861-865.

Blazer, D. G., Bachar, J. R., & Manton, K. G. (1986). Suicide in late life: Review

and commentary. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 43,216-221

Block, J. (1995). A contrarian view of the five-factor approach to personality

Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (1989). Applied logistic regression. New York:

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

description. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 187-215.

Buie, D. H., & Maltsberger, J. T. (1989). The psychological vulnerability to suicide. In D. Jacobs & H. N. Brown (Eds.), Suicide: Understanding and responding (pp. 59-72). Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

Burvill, P. W. (1995). Recent progress in the epidemiology of major depression.

Epidemiologic Reviews, 17, 21 -31.

Kagan, J. (with Snidman, N., Arcus, D., & Reznick, J. S.). (1994). Galen's

Centers for Disease Control. (1996). Suicide among older personsUnited

States, 1980-1992. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 45,3-6.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). GMWK250 death rates/or

72 selected causes, United States, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996 and 1997.

Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nchswww/data/gm250_97.pdf.

Chatterjee, S., & Hadi, A. J. (1988). Sensitivity analysis in linear regression.

New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

and Life-Threatening Behavior, 23, 21-26.

Clark, L. A., Watson, D., & Mineka, S. (1994). Temperament, personality, and

the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103,

103-116.

Cloninger, C. R., Svrakic, D. M., & Przybeck, T. R. (1993). A psychobiological

model of temperament and character. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50,

975-990.

Congressional Record. (1997). Resolution recognizing suicide as a national

health problem. (CR page S-4038, May 6).

Congressional Record. (1998). Resolution recognizing suicide as a national

problem (CR page H10309, October 9).

Conwell, Y, Duberstein, P. R., Cox, C., Herrmann, J., Forbes, N., & Caine, E.

D. (1996). Relationships of age and Axis I diagnosis in victims of completed suicide: A psychological autopsy study. American Journal of

Psychiatry, 153, 1001-1008.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1987). Neuroticism, somatic complaints, and

disease: Is the bark worse than the bite? Journal of Personality, 55,

299-316.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory

and NEO Five Factor Inventory': Professional manual. Odessa, FL:

Psychological Assessment Resources.

Costa, P. T, Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1995). Solid ground in the wetlands of personality: A reply to Block. Psychological Bulletin, 117,216-220.

Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor

model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41,417^440.

Duberstein, P. R. (1995). Openness to experience and completed suicide across

the second half of life. International Psychogeriatrics, 7,183-198.

Duberstein, P. R., Conwell, Y, & Caine, E. D. (1994). Age differences in the

personality characteristics of suicide completers: Preliminary findings from

a psychological autopsy study. Psychiatry, 57,1 \ 3-224.

Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide: A study in sociology. New York: Free Press (original work published in 1897).

Flett, G. L., Vredenburg, K., & Krames, L. (1997). The continuity of depression

in clinical and nonclinical samples. Psychological Bulletin, 121,395^116.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-Mental State: A

practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician.

Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189-198.

Gallo, J. J., Rabins, P. V., Lyketos, C., Tien, A. Y, & Anthony, J. C. (1997).

Depression without sadness: Functional outcomes of nondysphoric depression in later life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 45,570-578.

Hendin, H. (1991). Psychodynamics of suicide, with particular reference to the

young. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148,1150-1158.

Hill, R. D., Gallagher, D., Thompson, L. W., & Ishida, T. (1988). Hopelessness

as a measure of suicidal intent in the depressed elderly. Psychology and

Aging, 3, 230-232.

Hooker, K., Frazier, L. D., & Monahan, D. (1994). Personality and coping

among caregivers of spouses with dementia. Gerontologist, 34, 386-392.

Hooker, K., Monahan, D., Bowman, S. R., Frazier, L. D., & Shifren, K. (1998).

Personality counts for a lot: Predictors of mental and physical health of

spouse caregivers in two disease groups. Journal of Gerontology:

Psychological Sciences, 53B, P73-P85.

Hooker, K., Monahan, D., Shifren, K., & Hutchinson, C. (1992). Mental and

physical health of spouse caregivers: The role of personality. Psychology

and Aging, 7, 367-375.

in the natural language and questionnaires. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook

of personality: Theory and research (pp. 66-100). New York: Guilford.

prophecy: Temperament in human nature. New York: Basic Books.

Katz, I. R. (1996). On the inseparability of mental and physical health in aged

persons: Lessons from depression and medical comorbidity. American

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 4, 1-16.

Kessler, R. C., Borges, G., & Walters, E. E. (1999). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey.

Archives of General Psychiatry, 56,617-626.

Krause, N., Liang, J., & Keith, V. (1990). Personality, social support, and psychological distress in later life. Psychology and Aging, 5, 315-326.

Lebowitz, B. D., Pearson, J. L., Schneider, L. S., Reynolds III, C. F.,

Alexopoulos, G. S., Bruce, M. L., Conwell, Y, Katz, I. R., Meyers, B. S.,

Morrison, M. F., Mossey, J., Niederehe, G., & Parmelee, P. (1997).

Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life: Consensus statement update. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 1186-1190.

Linehan, M. M. (1986). Suicidal people: One population or two? Annals of the

New York Academy of Sciences, 487, 16-33.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Linehan, M. M., Chiles, J. A., Egan, K. J., Devine, R. H., & Laffaw, J. A.

(1986). Presenting problems of parasuicides versus suicide ideators and

nonsuicidal psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 6, 880-881.

Lyness, J. M., Duberstein, P. R., King, D. A., Cox, C., & Caine, E. D. (1998).

Medical illness burden, trait neuroticism, and depression in primary care elderly. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155,969-971.

Lyness, J. M., Noel, T. K., Cox, C., King, D. A., Conwell, Y, & Caine, E. D.

(1997). Screening for depression in elderly primary care patients. Archives

of Internal Medicine, 757,449-454.

Maris, R. W. (1992). The relationship of nonfatal suicide attempts to completed

suicide. In R. W. Maris, A. L. Berman, J. T. Maltsberger, & R. I. Yufit

(Eds.), Assessment and prediction of suicide (pp. 362-380). New York:

Guilford Press.

Marshall, G. N., Wortman, C. B., Vickers, R. R., Jr., Kusulas, J. W, & Hervig,

L. K. (1994). The five-factor model of personality as a framework for

personality-health research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

67, 278-286.

McAdams, D. P. (1994). Can personality change? Levels of stability and growth

in personality across the life span. In T. F. Heatherton & J. L. Weinberger

(Eds.), Can personality change? (pp. 299-314). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T, Jr. (1997). Personality trait structure as ahuman

universal. American Psychologist, 52, 509-516.

McCullagh, P., & Nelder, J. A. (1989). Generalized linear models (2nd ed).

New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Meehl, P. E. (1992). Factors and taxa, traits and types, differences of degree and

differences in kind. Journal of Personality, 60, 117-124.

Monk, M. (1987). Epidemiology of suicide. Epidemiologic Reviews, 9,51-69.

Moscicki, E. K. (1989). Epidemiologic surveys as tools for studying suicidal

behavior: A review. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 19,131-146.

National Institutes of Health. (1998). Priorities for prevention research at

NIMH: A report by the National Advisory Council Workgroup on Mental

Disorders Prevention Research. (NTH Publication No. 98-4321). Rockville,

MD: Author.

O'Carroll, P. W., Berman, A. L., Maris, R. W., Moscicki, E. K., Tanney, B. L.,

& Silverman, M. M. (1996). Beyond the Tower of Babel: A nomenclature

for suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 26,237-252.

Penninx, B. W. J. H., Geerlings, S. W., Deeg, D. J. H., van Eijk, J. T. M.,

van Tilburg, W., & Beekman, A. T. F. (1999). Minor and major depression

and the risk of death in older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56,

889-895.

Pfeffer, C. R., Stokes, P., & Shindledecker, R. (1991). Suicidal behavior and

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis indices in child psychiatric inpatients. Biological Psychiatry, 29,909-917.

Roy, A. (1998). Is introversion a risk factor for suicidal behaviour in depression? Psychological Medicine, 28, 1457-1461.

Rudd, M. D., Joiner, T, & Rajab, M. H. (1996). Relationships among suicide

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

Clark, D. C. (1993). Narcissistic crises of aging and suicidal despair. Suicide

John, O. P. (1990). The "Big Five" factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality

P26

DUBERSTEINETAL

ideators, attempters, and multiple attempters in a young adult sample.

Young, M. A., Fogg, L. F, Scheftner, W., Fawcett, J., Akiskal, H., & Maser, J.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 541-550.

Santor, D. A., Bagby, R. M., & Joffe, R. T. (1997). Evaluating stability and

change in personality and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psvchologv. 73,

1354-1362.

Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Gibbon, M. (1987). Structured clinical inten'iewfor DSM-/II-Rpatient version. New York: Biometrics Research

Department, NY State Psychiatric Institute.

Tellegen, A. (1985). Structures of mood and personality and their relevance to

assessing anxiety, with an emphasis on self-report (pp. 681-706). In A. H.

Tuma & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Anxiety and the anxiety disorders. Hillsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Unutzer, J., Katon, W., Sullivan, M., & Miranda, J. (1999). Treating depressed

older adults in primary care: Narrowing the gap between efficacy and effectiveness. Milbank Quarterly, 77, 225-256.

Von Dras, D. D., & Siegler, I. C. (1997). Stability in extraversion and aspects of

social support at midlife. Journal of Personality and Social Psvchologv, 72,

233-241.

(1996). Stable trait components of hopelessness: Baseline and sensitivity to

depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology; 105,155-165.

Zubenko, G. S., Mulsant, B. H., Sweet, R. A., Pasternak, R. E., & Tu, X. M.

(1997). Mortality of elderly patients with psychiatric disorders. American

Journal of Psychiatry. 150, 1687-1692.

Zweig, R. A., & Hinrichsen, G. A. (1993). Factors associated with suicide attempts by depressed older adults: A prospective study. American Journal of

Psychiatrv, 150, 1687-1692.

Received August 12. 1998

Accepted August 18, 1999

Decision Editor: Toni C. Antonucci, PhD

The 53rd Annual Scientific Meeting of

The Gerontological Society of America

November 17-21, 2000, Washington, D.C

Abstracts due April 3, 2000. See www.geron.org for details.

Downloaded from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on February 26, 2015

CALL FOR PAPERS!

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Ogden 2006Document16 pagesOgden 2006A.VictorPas encore d'évaluation

- Ak KeshotDocument13 pagesAk KeshothagagahajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Project On Offences Affecting Administration of JusticeDocument22 pagesProject On Offences Affecting Administration of JusticeRajeev VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- Is There Any Democracy Fo Indegineous PeopleDocument2 pagesIs There Any Democracy Fo Indegineous PeopleChristianPas encore d'évaluation

- NuisanceDocument42 pagesNuisanceChoco Skate100% (1)

- Robert Preston Whyte - Construction of Surfing Space in Durban, South AfricaDocument24 pagesRobert Preston Whyte - Construction of Surfing Space in Durban, South AfricaSalvador E MilánPas encore d'évaluation

- Feminism Regained: Exposing The Objectification of Eve in John Milton's Paradise LostDocument21 pagesFeminism Regained: Exposing The Objectification of Eve in John Milton's Paradise LostHaneen Al IbrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- Characteristics, Processes and Ethics of ResearchDocument4 pagesCharacteristics, Processes and Ethics of ResearchRellie CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Timothy A. Brown Tracy A. O'Leary David H. BarlowDocument55 pagesGeneralized Anxiety Disorder: Timothy A. Brown Tracy A. O'Leary David H. BarlowCamila JoaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gyford Catalog 2015 enDocument164 pagesGyford Catalog 2015 enAnonymous NwnJNOPas encore d'évaluation

- Introductions and ConclusionsDocument4 pagesIntroductions and ConclusionsdimmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Healthy Relationship ChecklistDocument4 pagesHealthy Relationship ChecklistNajma Sadiq100% (1)

- Leo J. Elders - The Metaphysics of Being of St. Thomas Aquinas in A Historical Perspective (Studien Und Texte Zur Geistesgeschichte Des Mittelalters) - Brill Academic Publishers (1993) PDFDocument156 pagesLeo J. Elders - The Metaphysics of Being of St. Thomas Aquinas in A Historical Perspective (Studien Und Texte Zur Geistesgeschichte Des Mittelalters) - Brill Academic Publishers (1993) PDFLucas LagassePas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Ethics: A Case StudyDocument2 pagesEngineering Ethics: A Case StudyMirae AlonPas encore d'évaluation

- Culture of Fear-Frank FurediDocument204 pagesCulture of Fear-Frank FurediAlejandra Aguilar100% (3)

- The Dark Style of Se7enDocument4 pagesThe Dark Style of Se7enAnitaPas encore d'évaluation

- GP Essay Skills 2012Document13 pagesGP Essay Skills 2012Audrey JongPas encore d'évaluation

- GE PTW Confined SpacesDocument2 pagesGE PTW Confined SpacesKural MurugesanPas encore d'évaluation

- Motion of Brianna Nelson and VN To Clarify or Reconsider The July 29,2016 Genetic Testing OrderDocument6 pagesMotion of Brianna Nelson and VN To Clarify or Reconsider The July 29,2016 Genetic Testing OrderLaw&CrimePas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study - 5Document11 pagesCase Study - 5krati123chouhanPas encore d'évaluation

- UnilabDocument6 pagesUnilabKim LaguardiaPas encore d'évaluation

- I Love You I Hate You - Elizabeth DavisDocument232 pagesI Love You I Hate You - Elizabeth Davisalexandra ene100% (1)

- Right To Command, and Correlatively, The Right To Be Obeyed" (Reiman 230) - Wolff Views PowerDocument4 pagesRight To Command, and Correlatively, The Right To Be Obeyed" (Reiman 230) - Wolff Views PowerDisneyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dowry Prohibition ActDocument40 pagesThe Dowry Prohibition ActBanglamunPas encore d'évaluation

- Virtues and VicesDocument53 pagesVirtues and VicesTorong VPas encore d'évaluation

- Pasco EmnaceDocument40 pagesPasco EmnacekuheDSPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Forms DigestDocument2 pagesLegal Forms DigestKMPas encore d'évaluation

- Soriano vs. MTRCBDocument45 pagesSoriano vs. MTRCBDawn Jessa GoPas encore d'évaluation

- Classical Ethical Theories NewDocument49 pagesClassical Ethical Theories NewBBAM I 2014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Appellants' Reply BriefDocument20 pagesAppellants' Reply BriefAnita Belle100% (1)