Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Causes

Transféré par

ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκη0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

7 vues4 pagesw

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentw

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

7 vues4 pagesCauses

Transféré par

ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηw

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme TXT, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 4

Hi there.

In the previous video, we looked at

the results of the trust question.

And to be fair we were pretty critical

about land surveys in general,

and about the trust

question in particular.

Well, in this video,

we're going to look at what social

scientists actually do with the results.

We'll look at some of

the assumptions that they make.

We'll examine some of the plausible

hypotheses about the role of

trust in society.

Now there's a large body of literature

on what determines trust and

it's divided itself into three mutually

incompatible rival schools of thought.

There are those who argue that

trust is deeply culturally rooted,

that it belongs almost to the values

learned in early childhood.

Among the evidence they site to support

this claim is that trust levels of

those in an immigrant group reflect

those in the home country rather than in

the host country,

even after several generations.

Other social scientists believe that trust

is a learned phenomenon that is part of

one's process of socialization.

Robert Putnam is one of these.

He and others cite the evidence

of a link between trust and

institutional membership, and

participation in civic society.

As they're yet another group that also

believes that trust is learned, but

they contend that the mechanism is not

socialization but one of confidence.

They point to the evident relationship

between well ordered societies and

recorded levels of interpersonal trust.

The World Values Survey

collects the results of

the trust question in the form of

a single index on a separate webpage.

Some of the observations date

from the turn of the millennium.

They're 15 years old.

Does this matter?

Well it doesn't if you believe that trust

attitudes are relatively constant and

fluctuate at the most

within a small range.

And that's seems to be

the assumption underlying their use.

Culturalists span their

expectations over generations.

Institutionalists discuss changes

taking place over decades.

And the only breach that

the governance school has discovered,

is the deep changes in trust

accompanying major regime changes,

such as the collapse of communism

at the end of the 1990s.

But does this belief withstand closer

examination of the recent data?

In many instances,

the latest world value survey results do

indeed coincide well with

the results of earlier surveys, but

there are exceptions, and

here are some examples.

The Netherlands for example, which is

drifting in an economic malaise since

the financial crisis of 2008, has actually

improved it's index by a whole 25 points.

Thailand, which once formed part of

the explanation that high trust level is

reflected in it's traditional

Buddhist values, fell by 18 points.

No doubt because of the political

problems in the country.

But there again Egypt,

which has been through at

least one social political revolution to

the Arab Spring, remains almost unchanged.

By contrast Jordan, possibly under

the impact of the Syrian refugee crisis,

has seen it's trust score by 34 points.

And the largest change of all is the

collapse of trust in Ecuador, from 72.7 to

14.5, taking them from 22nd in the world

rankings right down to 7th from bottom.

A second assumption made by social

scientists is that there is

a direct link between

interpersonal trust and

generalized trust placed

in government institutions.

The evidence of the latter is

not as widely available as for

the former, nor over a similar time span.

But there is support in local and

regional studies for this assumption.

I however have a sneaking suspicion

that those answering this question will

have difficulty in separating

the institution of

government from the actual

government in power.

Now, throughout this lecture we've

argued the pivotal role played by

trust in society.

Well now, let's try to operationalize that

assumption with a series of hypotheses.

These hypotheses will follow

a track leading from homogeneity in

society to levels of trust, from levels

of trust to the quality of governance,

and from the quality of governance

to economic growth and prosperity.

First, we could argue that the more

homogeneous a society is in

terms of ethnic composition,

religious diversity, and income and

wealth equality, the higher is

likely to be its level of trust.

Large differences within society

make it more difficult to

engage in activities that allow

the creation of bridging capital.

In the presence of a clearly

defined outsider pushes people

into associations that encourage

inward looking bonding capital.

Second, we could argue

the higher the levels of trust,

the better the quality of governance.

In a high trust society, you will

allow non-group members to act on your

behalf in the belief that they will act in

the interest of society as a whole, and

not for the narrow sectional

interests of their own.

Thirdly, we could argue that

good governance will lead to

better economic performance.

That the fact that governments will

operate efficiently and predictably will

create conditions of confidence and alter

the planning scenarios for investment.

Citizens will be willing to defer

immediate consumption in the form of

savings or taxation for the certain

expectation of returns in the future.

Investment scenarios by business will

improve and the extra capital will act as

a transmission belt for

economic growth and prosperity.

Of course,

we can always reverse the causation.

Prosperity allows a society to divert

more resources to good governance.

Economic growth allows

greater expenditure of

government without competing

with current consumption.

Extra levels of public provision,

especially in education,

also contribute to higher levels of trust.

Moreover, knowing that institutions

work removes the need for

bribery and corruption.

And this too would filter back into

enhancing levels of interpersonal trust.

A confidence in good governance in terms

of openness and transparency, as well

as the efficient provision of public

goods, would also reduce the incentive for

social groups, however defined,

to grab shares for themselves.

And this, again,

will reduce the relevance of homogeneity

as an operational factor in society.

Let's sum up then.

In this video,

we've looked at the assumptions made

about the causes of interpersonal trust.

We've looked at whether trust levels

are stable, and whether interpersonal and

generalized trust are linked.

We've also examined the causal

chain linking homogeneity to trust,

to governance, and to economic progress,

and we've looked at the reverse causation.

Now, in this video, we've continually

talked about links between factors.

Such links may be logical.

But the foundation of much social science,

and

particularly political economy, is that

they are also statistically verifiable.

And in the next video we'll

examine how this is done.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 2 - 5 - Light (5 - 48)Document3 pages2 - 5 - Light (5 - 48)ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - 7 - Week 1 - Lecture 6 (11m20s)Document6 pages1 - 7 - Week 1 - Lecture 6 (11m20s)ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - 6 - Week 1 - Lecture 5 (7m51s)Document4 pages1 - 6 - Week 1 - Lecture 5 (7m51s)ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Deducing The LocationDocument4 pagesDeducing The LocationΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Map of GDP PPPDocument2 pagesMap of GDP PPPΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - 5 - Week 1 - Lecture 4 (8m43s)Document5 pages1 - 5 - Week 1 - Lecture 4 (8m43s)ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - 4 - Week 1 - Lecture 3 (7m37s)Document5 pages1 - 4 - Week 1 - Lecture 3 (7m37s)ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Movements and Cone of ConfusionDocument2 pagesMovements and Cone of ConfusionΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - 3 - Week 1 - Lecture 2 (6m52s)Document4 pages1 - 3 - Week 1 - Lecture 2 (6m52s)ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - 2 - Week 1 - Lecture 1 (6m52s)Document4 pages1 - 2 - Week 1 - Lecture 1 (6m52s)ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- PovertyDocument4 pagesPovertyΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is SoundDocument3 pagesWhat Is SoundΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- World MapsDocument2 pagesWorld MapsΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- GDP Current ValuesDocument4 pagesGDP Current ValuesΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- GDP PPPDocument4 pagesGDP PPPΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Map of Ethnic FragmentationDocument1 pageMap of Ethnic FragmentationΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Map of GDPDocument2 pagesMap of GDPΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Map of PopulationDocument2 pagesMap of PopulationΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Map of Linguistic DiversityDocument2 pagesMap of Linguistic DiversityΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Political EconomyDocument3 pagesPolitical EconomyΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Configuring The WorldDocument3 pagesConfiguring The WorldΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- PopulationDocument4 pagesPopulationΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - 1 - Introduction (5 - 35)Document3 pages2 - 1 - Introduction (5 - 35)ΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Linguistic FragmentationDocument4 pagesLinguistic FragmentationΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκη100% (1)

- Map of Religious DiversityDocument1 pageMap of Religious DiversityΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethnic FragmentationDocument4 pagesEthnic FragmentationΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Religious FragmentationDocument4 pagesReligious FragmentationΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Correlation and RegressionDocument4 pagesCorrelation and RegressionΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- Map of TrustDocument2 pagesMap of TrustΕιρήνηΔασκιωτάκηPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- DINDIGULDocument10 pagesDINDIGULAnonymous BqLSSexOPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonDocument7 pagesWhat Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonMichael VladislavPas encore d'évaluation

- 14 Jet Mykles - Heaven Sent 5 - GenesisDocument124 pages14 Jet Mykles - Heaven Sent 5 - Genesiskeikey2050% (2)

- MC-SUZUKI@LS 650 (F) (P) @G J K L M R@601-750cc@175Document103 pagesMC-SUZUKI@LS 650 (F) (P) @G J K L M R@601-750cc@175Lanz Silva100% (1)

- Prac Research Module 2Document12 pagesPrac Research Module 2Dennis Jade Gascon NumeronPas encore d'évaluation

- As If/as Though/like: As If As Though Looks Sounds Feels As If As If As If As Though As Though Like LikeDocument23 pagesAs If/as Though/like: As If As Though Looks Sounds Feels As If As If As If As Though As Though Like Likemyint phyoPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 6107116501871886934Document38 pages5 6107116501871886934Harsha VardhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit I. Phraseology As A Science 1. Main Terms of Phraseology 1. Study The Information About The Main Terms of PhraseologyDocument8 pagesUnit I. Phraseology As A Science 1. Main Terms of Phraseology 1. Study The Information About The Main Terms of PhraseologyIuliana IgnatPas encore d'évaluation

- NBPME Part II 2008 Practice Tests 1-3Document49 pagesNBPME Part II 2008 Practice Tests 1-3Vinay Matai50% (2)

- 1120 Assessment 1A - Self-Assessment and Life GoalDocument3 pages1120 Assessment 1A - Self-Assessment and Life GoalLia LePas encore d'évaluation

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Moment Musicaux Op No in E MinorDocument12 pagesSergei Rachmaninoff Moment Musicaux Op No in E MinorMarkPas encore d'évaluation

- Operational Risk Roll-OutDocument17 pagesOperational Risk Roll-OutLee WerrellPas encore d'évaluation

- Pharmaceuticals CompanyDocument14 pagesPharmaceuticals CompanyRahul Pambhar100% (1)

- Leku Pilli V Anyama (Election Petition No 4 of 2021) 2021 UGHCEP 24 (8 October 2021)Document52 pagesLeku Pilli V Anyama (Election Petition No 4 of 2021) 2021 UGHCEP 24 (8 October 2021)Yokana MugabiPas encore d'évaluation

- Digi-Notes-Maths - Number-System-14-04-2017 PDFDocument9 pagesDigi-Notes-Maths - Number-System-14-04-2017 PDFMayank kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Ethics AssignmentDocument12 pagesProfessional Ethics AssignmentNOBINPas encore d'évaluation

- Joint School Safety Report - Final ReportDocument8 pagesJoint School Safety Report - Final ReportUSA TODAY NetworkPas encore d'évaluation

- Mari 1.4v2 GettingStartedGuide PDFDocument57 pagesMari 1.4v2 GettingStartedGuide PDFCarlos Vladimir Roa LunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consent 1095 1107Document3 pagesConsent 1095 1107Pervil BolantePas encore d'évaluation

- DLL - Science 6 - Q3 - W3Document6 pagesDLL - Science 6 - Q3 - W3AnatasukiPas encore d'évaluation

- Skin Yale University Protein: Where Does Collagen Come From?Document2 pagesSkin Yale University Protein: Where Does Collagen Come From?Ellaine Pearl AlmillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Opportunity, Not Threat: Crypto AssetsDocument9 pagesOpportunity, Not Threat: Crypto AssetsTrophy NcPas encore d'évaluation

- Ten - Doc. TR 20 01 (Vol. II)Document309 pagesTen - Doc. TR 20 01 (Vol. II)Manoj OjhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arpia Lovely Rose Quiz - Chapter 6 - Joint Arrangements - 2020 EditionDocument4 pagesArpia Lovely Rose Quiz - Chapter 6 - Joint Arrangements - 2020 EditionLovely ArpiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Law Scope and RegulationDocument21 pagesCorporate Law Scope and RegulationBasit KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Step-By-Step Guide To Essay WritingDocument14 pagesStep-By-Step Guide To Essay WritingKelpie Alejandria De OzPas encore d'évaluation

- Apple NotesDocument3 pagesApple NotesKrishna Mohan ChennareddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Autos MalaysiaDocument45 pagesAutos MalaysiaNicholas AngPas encore d'évaluation

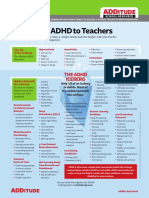

- Explaining ADHD To TeachersDocument1 pageExplaining ADHD To TeachersChris100% (2)

- GASB 34 Governmental Funds vs Government-Wide StatementsDocument22 pagesGASB 34 Governmental Funds vs Government-Wide StatementsLisa Cooley100% (1)