Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Sacrifice (Chess)

Transféré par

lyna_mada_yahooCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sacrifice (Chess)

Transféré par

lyna_mada_yahooDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

3/29/2015

Sacrifice (chess) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sacrifice (chess)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In chess, a sacrifice is a move giving up a piece in the hopes of

gaining tactical or positional compensation in other forms. A sacrifice

could also be a deliberate exchange of a chess piece of higher value

for an opponent's piece of lower value.

Any chess piece except the king may be sacrificed. Because players

usually try to hold on to their own pieces, offering a sacrifice can

come as an unpleasant surprise to one's opponent, putting him off

balance and causing much precious time to be wasted trying to

calculate whether the sacrifice is sound or not and whether to accept

it. Sacrificing one's queen (the most valuable piece), or a string of

pieces, adds to the surprise, and such games can be awarded

brilliancy prizes.[1]

1

a

The move 6. Bxf7+ is a bishop sacrifice.

Contents

1 Types of sacrifice

1.1 Real versus sham

1.1.1 Real sacrifices

1.1.2 Sham sacrifices

1.2 Other types of sacrifices

1.2.1 Forced versus non-forced

2 Examples

2.1 Deflection sacrifice

2.2 Sacrifice to avoid losing

2.3 Non-forcing sacrifice

2.4 Positional sacrifice

2.5 Sacrifice to checkmate

2.6 Queen sacrifice leads to smothered checkmate

3 See also

4 Notes

5 References

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrifice_(chess)

1/8

3/29/2015

Sacrifice (chess) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Types of sacrifice

Real versus sham

Rudolf Spielmann proposed a division between sham and real sacrifices:

In a real sacrifice, the sacrificing player will often have to play on with less material than his opponent for

quite some time.

In a sham sacrifice, the player offering the sacrifice will soon regain material of the same or greater value, or

else force mate. A sham sacrifice of this latter type is sometimes known as a pseudo sacrifice.[2]

In compensation for a real sacrifice, the player receives dynamic advantages which he must capitalize on, or risk

losing the game due to the material deficit. Because of the risk involved, real sacrifices are also called speculative

sacrifices.

Real sacrifices

Attack on the king. A player might sacrifice a pawn or piece to get open lines around the vicinity of the

opponent's king, to get a kingside space advantage, to destroy or damage the opposing king's pawn cover, or to

keep the opposing king in the center. Unless the opponent manages to fend off the attack, he is likely to lose. The

Greek gift sacrifice is a canonical example.

Development. It is common to give up a pawn in the opening to speed up one's development. Gambits typically

fall into this category. Developing sacrifices are frequently returned at some point by the opponent before the

development edge can turn into a more substantial threat such as a kingside attack.

Strategic/positional. In a general sense, the aim of all real sacrifices is to obtain a positional advantage. However,

there are some speculative sacrifices where the compensation is in the form of an open file or diagonal or a

weakness in the opponent's pawn structure. These are the hardest sacrifices to make, requiring deep strategic

understanding.

Sham sacrifices

Checkmate. A common benefit of making a sacrifice is to allow the sacrificing player to checkmate the opponent.

Since checkmate is the ultimate goal of chess, the loss of material (see Chess piece relative value) does not matter

in a successful checkmate. Sacrifices leading to checkmate are typically forcing, and often checks, leaving the

opponent with only one or a few options (example, checking the king with the knight, queen takes the knight, then

rook checkmates the king with absence on the queen).

Avoiding loss. The counterpart to the above is saving a lost game. A sacrifice could be made to force stalemate or

perpetual check, to create a fortress, or otherwise force a draw, or to avoid even greater loss of material.

Material gain. A sacrifice might initiate a combination that results in an overall material gain, making the upfront

investment of the sacrifice worthwhile. A sacrifice leading to a pawn promotion is a special case of this type of

sacrifice.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrifice_(chess)

2/8

3/29/2015

Sacrifice (chess) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Simplification. Even if the sacrifice leads to net material loss for the foreseeable future, the sacrificing player may

benefit because they are already ahead in material and the exchanges simplify the position making it easier to win. A

player ahead in material may decide that it is worthwhile to get rid of one of the last effective pieces the opponent

has.

The tactical sham sacrifices can be categorized further by the mechanism in why the sacrifice is made. Some

sacrifices may fall into more than one category.[3]

In deflection sacrifices the aim is to distract one of the opponent's pieces from a square where it is

performing a particular duty.

In destruction sacrifices a piece is sacrificed in order to knock away a materially inferior, but tactically

more crucial piece, so that the sacrificing player can gain control over the squares the taken chessman

controlled.

A magnet sacrifice is similar to a deflection sacrifice, but the motivation behind a magnet sacrifice is to pull

an opponent's piece to a tactically poor square, rather than pulling it away from a crucial square.

In a clearance sacrifice the sacrificing player aims to vacate the square the sacrificed piece stood on, either

to open up for his own pieces, or to put another, more useful piece on the same square.

In a tempo sacrifice, the sacrificing player abstains from spending time to prevent the opponent from

winning material because the time saved can be used for something even more beneficial, for example

pursuing an attack on the king or guiding a passed pawn towards promotion.

In a suicide sacrifice, the sacrificing player aims to rid himself of the remaining pieces capable of performing

legal moves, and thereby obtain a stalemate and a draw from a poor position.

Other types of sacrifices

Forced versus non-forced

Another way to classify sacrifices is to distinguish between forcing and non-forcing sacrifices. The former type

leave the opponent with no option but acceptance, typically because not doing so would leave them behind in

material with no compensation. Non-forcing sacrifices, on the other hand, give the opponent a choice. A common

error is to not recognize when a particular sacrifice can be safely declined with no ill-effects.

Examples

Deflection sacrifice

In the diagram,[4] GM Aronian's queen on d3 is at the top of the ladder, and his rook on d1 represents the bottom.

He mistakenly played 24. exd4??, opening up the e-file for Black's rook. After Svidler played 24... Re1+!,

Aronian was forced to resign, because Black's move forces the reply 25. Rxe1 (or 25. Qf1 Qxf1#), after which

White's queen is undefended and therefore lost.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrifice_(chess)

3/8

3/29/2015

Sacrifice (chess) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Aronian vs. Svidler

Tal Memorial Tournament, Moscow 2006

a

1

a

This particular type of sacrifice has also been called the "Hook and

Ladder trick", for the white queen is precariously at the top of the

"ladder", while the rook is at the bottom, supporting it.[5]

Position after 24. exd4??

Sacrifice to avoid losing

Evans vs. Reshevsky, New York 1963

a

1

a

Black played 1... Qxg3? and White drew with 2. Qg8+! Kxg8 (on

any other move Black will get mated) 3. Rxg7+!. White intends to

keep checking on the seventh rank, and if Black ever captures the

rook it is stalemate.[6]

This save from Evans has been dubbed "The Swindle of the

Century".[7] White's rook is known as a desperado.

Black to move

Non-forcing sacrifice

This time Reshevsky is at the receiving end of a sacrifice.[8] White has just played h2h4. If Black takes the knight

he has to give up his own knight on f6 to avoid mate on h7. Instead, he simply ignored the bait and continued

developing.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrifice_(chess)

4/8

3/29/2015

Sacrifice (chess) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Najdorf vs. Reshevsky, New York 1952

a

1

a

Position after 13... h6 14. h4

Positional sacrifice

Spassky vs. Tal, Moscow 1971

a

1

a

In this game[9] Black played 14... d4! 15. Nxd4 Nd5. In exchange

for the sacrificed pawn, Black has obtained a semi-open file, a

diagonal, an outpost on d5 and saddled White with a backward

pawn on d3. The game was eventually drawn.

Black played 14... d4

Sacrifice to checkmate

The following example features a forced bishop sacrifice by White. White can force mate in two moves in the

diagram at left as follows: 1. Bg6+ hxg6 2. Qxg6#

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrifice_(chess)

5/8

3/29/2015

Sacrifice (chess) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1

a

White to move

Queen sacrifice leads to smothered checkmate

McConnell vs. Morphy, New Orleans 1849

a

1

a

In this position, Black moves 22. ... Qg1+ forcing the white rook

to take black's queen by 23. Rxg1 ; the king cannot take the

queen because it would have been in check from the knight on h3.

Having forced the rook out of a position where it was defending

the f-file and into a position where it blocked the king from making

any move, the black knight delivers a smothered mate by 23. ...

Nf2# .[10]

22. ... Black to move

See also

Exchange sacrifice

Queen sacrifice

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrifice_(chess)

6/8

3/29/2015

Sacrifice (chess) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Desperado

Chess tactics

Chess terminology

The Game of the Century

Dragoljub Mini a game shows the sacrifice of a rook for a tempo.

Notes

1. Horowitz, Al (December 28, 1967). "Chess:; A 23-Move Bind Winds Up With Brilliant Queen Sacrifice"

(http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FA0E14F73E541B7B93C3A8178FD85F4C8685F9). The New

York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

2. Rudolf Spielman, "The Art of Sacrifice in Chess", 1995, Dover, ISBN 0-486-28449-2

3. This classification scheme was presented by Hans Olav Lahlum in a series of articles in Norsk Sjakkblad, no. 2

2006 (http://sjakk.no/nsf/norsk_sjakkblad/06_nr2.pdf) (p. 44), no. 3 2006

(http://sjakk.no/nsf/norsk_sjakkblad/06_nr3.pdf) (p. 44), no. 4 2006

(http://sjakk.no/nsf/norsk_sjakkblad/06_nr4.pdf) (p. 44), no. 5 2006

(http://sjakk.no/nsf/norsk_sjakkblad/06_nr5.pdf) (p. 35), and no. 6 2006

(http://sjakk.no/nsf/norsk_sjakkblad/06_nr6.pdf) (p. 31) (Norwegian)

4. "Levon Aronian vs Peter Svidler (2006)" (http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1434844).

ChessGames.com. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

5. The Hook & Ladder Trick (http://beta.uschess.org/frontend/magazine_124_313.php) Chess Life Dana Mackenzie

6. Evans vs. Reshevsky, USA 1963 (http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1252040)

7. Stalemate! (http://www.michess.org/webzine_199907/okeefe.shtml) Jack OKeefe, Michigan Chess Association.

8. Najdorf vs. Reshevsky, 1952 (http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1101209)

9. Spassky vs. Tal, 1971 (http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1128868)

10. "chessgames.com" (http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1075508). pp. James McConnell vs. Paul

Morphy, New Orleans 1849. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

References

Andrew Soltis. The Art of Defense in Chess. McKay Chess Library, 1975. ISBN 0-679-14108-1.

Leonid Shamkovich. The Modern Chess Sacrifice. Tartan Books, 1978. ISBN 0-679-14103-0.

Israel Gelfer. Positional Chess Handbook. B. T. Batsford Ltd., 1991. ISBN 0-7134-6395-3.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sacrifice_(chess)&oldid=646382031"

Categories: Chess tactics Chess terminology

This page was last modified on 9 February 2015, at 18:40.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrifice_(chess)

7/8

3/29/2015

Sacrifice (chess) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply.

By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered trademark

of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrifice_(chess)

8/8

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Programmes: The Official Selection - The Main Event of The FestivalDocument1 pageProgrammes: The Official Selection - The Main Event of The Festivallyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Parallel Sections - These Are Non-Competitive Programmes Dedicated To Discovering OtherDocument1 pageParallel Sections - These Are Non-Competitive Programmes Dedicated To Discovering Otherlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Edward Aloysius Murphy, JRDocument1 pageEdward Aloysius Murphy, JRlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Cannes Film FestivalDocument2 pagesCannes Film Festivallyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- History: Jean Zay French Minister of National EducationDocument1 pageHistory: Jean Zay French Minister of National Educationlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Caméra D'or Un Certain RegardDocument1 pageCaméra D'or Un Certain Regardlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact: European Films ISBN 0333752104Document1 pageImpact: European Films ISBN 0333752104lyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess HistoryDocument1 pageChess Historylyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- International Critics' Week French Union of Film CriticsDocument1 pageInternational Critics' Week French Union of Film Criticslyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Shatranj Islamic Arabian Europe Byzantine Empire Southern Europe Norman Conquest of EnglandDocument1 pageShatranj Islamic Arabian Europe Byzantine Empire Southern Europe Norman Conquest of Englandlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess HistoryDocument1 pageChess Historylyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual Fritz9Document95 pagesManual Fritz9lyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual DGTDocument16 pagesManual DGTlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Rules of Chess960 (Fischer Random Chess) : Chess960 Uses Algebraic Notation ExclusivelyDocument6 pagesRules of Chess960 (Fischer Random Chess) : Chess960 Uses Algebraic Notation Exclusivelylyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Middle Persian Ferdowsi Raja English British Museum Hind ChosroesDocument1 pageMiddle Persian Ferdowsi Raja English British Museum Hind Chosroeslyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess HistoryDocument1 pageChess Historylyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Al-Ghazali Good Disposition: The Alchemy of HappinessDocument1 pageAl-Ghazali Good Disposition: The Alchemy of Happinesslyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Soyot Turkic Language: FirzānDocument1 pageSoyot Turkic Language: Firzānlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess History: Original Name Modern Name Original MoveDocument2 pagesChess History: Original Name Modern Name Original Movelyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess HistoryDocument1 pageChess Historylyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Middle East Plurale Tantum: Libro de Los JuegosDocument1 pageMiddle East Plurale Tantum: Libro de Los Juegoslyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Die Hindu Abu Al-Hasan 'Alī Al-Mas'ūdī Military Strategy Mathematics Gambling Astronomy Ivory Backgammon NushirwanDocument1 pageDie Hindu Abu Al-Hasan 'Alī Al-Mas'ūdī Military Strategy Mathematics Gambling Astronomy Ivory Backgammon Nushirwanlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess HistoryDocument2 pagesChess Historylyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Cox-Forbes Theory Hiram Cox Duncan Forbes ChaturajiDocument1 pageCox-Forbes Theory Hiram Cox Duncan Forbes Chaturajilyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Sanskrit Backgammon: AshtāpadaDocument1 pageSanskrit Backgammon: Ashtāpadalyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess HistoryDocument1 pageChess Historylyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Iran (Persia) : Iranian Shatranj Fritware New York Metropolitan Museum of ArtDocument2 pagesIran (Persia) : Iranian Shatranj Fritware New York Metropolitan Museum of Artlyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess HistoryDocument1 pageChess Historylyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess Tournament World Chess Championship Chess Theory Fide Computers Online GamingDocument1 pageChess Tournament World Chess Championship Chess Theory Fide Computers Online Gaminglyna_mada_yahooPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Heisman Dan - Everyone's 2nd Chess Book-Thinkers' Press (2005)Document127 pagesHeisman Dan - Everyone's 2nd Chess Book-Thinkers' Press (2005)roland usonPas encore d'évaluation

- Omega GambitDocument11 pagesOmega GambitmpollinniPas encore d'évaluation

- Lead Sheets 09-11Document15 pagesLead Sheets 09-11nikitakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Botvinnik-Smyslov Games 14 17 PDFDocument11 pagesBotvinnik-Smyslov Games 14 17 PDFjuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Liew - The Chigorin Defence - Move by Move 2018 Ocr Amp BMDocument341 pagesLiew - The Chigorin Defence - Move by Move 2018 Ocr Amp BMazazel100% (4)

- Interview With Kasparov About Mikhail TalDocument10 pagesInterview With Kasparov About Mikhail TalEverton AmarillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mating PatternsDocument13 pagesMating PatternsRenukha PannalaPas encore d'évaluation

- (Pe) g6 - Board GamesDocument11 pages(Pe) g6 - Board Gamesastraeax pandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Abnormal UsageDocument18 pagesAbnormal UsageGTR CoordinationPas encore d'évaluation

- Meadley CGM WatsonDocument93 pagesMeadley CGM WatsonIan ShanahanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lakdawala - Cyrus - Larsen - Move - by - Move PDFDocument254 pagesLakdawala - Cyrus - Larsen - Move - by - Move PDFRadu-Cristian Fotescu100% (3)

- Susan Polgar - Watch The QueenDocument5 pagesSusan Polgar - Watch The QueenRenukha PannalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Solitaire ChessDocument9 pagesSolitaire ChessJohnDave Muhex PoncedeLeon100% (1)

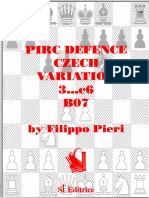

- Pieri Filippo Pirc Defence Czech Variation 3 c6 b07Document207 pagesPieri Filippo Pirc Defence Czech Variation 3 c6 b07Βαγγέλης Μισθός100% (1)

- SCL AL00线路图 (4A) PDFDocument69 pagesSCL AL00线路图 (4A) PDFSmartFix agudeloPas encore d'évaluation

- Neistadt - Practical Chess - 803 Chess Puzzles TO SOLVE - BWC PDFDocument134 pagesNeistadt - Practical Chess - 803 Chess Puzzles TO SOLVE - BWC PDFpablomatus0% (1)

- DocportalDocument2 pagesDocportalkidocrossPas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook of Chess CompositionDocument71 pagesHandbook of Chess CompositionAnonymous OFQuRiZOUzPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesChess Lesson PlanBaby ZoePas encore d'évaluation

- ChessDocument25 pagesChessRicardo Martinez100% (1)

- B73 Sicilian Dragon: 41 Characteristic Chess PuzzlesDocument14 pagesB73 Sicilian Dragon: 41 Characteristic Chess PuzzlesBill HarveyPas encore d'évaluation

- Mastering The Center IM Mat Kolosowski: The Material Is Divided Into 3 ChaptersDocument4 pagesMastering The Center IM Mat Kolosowski: The Material Is Divided Into 3 ChaptersAdrian Andres Szoichet EscobarPas encore d'évaluation

- Intro To Chess SyllabusDocument2 pagesIntro To Chess SyllabusTolis ApostolouPas encore d'évaluation

- CN 07Document23 pagesCN 07Ed BoldtPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade CorrelationsDocument1 pageGrade CorrelationsMarcela Costa67% (6)

- U17 Tripura State Selection Prospectus 2023Document4 pagesU17 Tripura State Selection Prospectus 2023Arijit SahaPas encore d'évaluation

- DynamicSystems - Boris AvrukhDocument19 pagesDynamicSystems - Boris AvrukhIulian BugescuPas encore d'évaluation

- Diaphragm ForceDocument3 pagesDiaphragm ForceMưa Vô HìnhPas encore d'évaluation

- Lane 44Document11 pagesLane 44Brody MalonePas encore d'évaluation

- Witson MceDocument12 pagesWitson MceJohn SmithPas encore d'évaluation