Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Bouffard Et Al (2005) - Influence of Achievement Goals and Self-Efficacy

Transféré par

Lanz OlivesTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Bouffard Et Al (2005) - Influence of Achievement Goals and Self-Efficacy

Transféré par

Lanz OlivesDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY, 2005, 40 (6), 373384

Influence of achievement goals and self-efficacy on

students self-regulation and performance

There`se Bouffard, Maryse Bouchard, Genevie`ve Goulet, Isabelle Denoncourt, and

Nathalie Couture

Universite du Quebec a` Montreal, Canada

t is widely admitted that low self-efficacy has a detrimental impact on the functioning and performance of a

person mainly concerned with performance goals but has no impact when a person is mainly concerned with

learning goals (Dweck, 1986). However, results from both correlational and experimental studies are divergent.

Since these studies examined very few indicators of participants cognitive functioning, they may have failed to

detect those aspects that could be more vulnerable to a negative impact of the combination of performance goals

and low self-efficacy. Another concern is the lack of most studies to clearly distinguish the type of performance

goal examined, particularly the performance-avoidance versus the performance-approach goal. In the current

study, we decided to focus on performance-approach and learning goals in order to examine how self-efficacy

intervenes in their effects on participants self-regulation and performance on a cognitive task. One hundred and

forty participants (85 females and 55 males) were examined. They were randomly assigned either to the learning

or the performance-approach goals condition. In each condition, half of the participants received feedback

aimed at inducing either high or low self-efficacy beliefs with regard to the task prior to executing it aloud.

Examination of participants verbal reports, direct observation of some of their behaviours while solving the

task, and responses to a retrospective questionnaire allowed the assessment of several indicators of their selfregulation and performance. As already reported by many studies, self-efficacy influenced various aspects of

participants self-regulation and performance. However, contrary to Dwecks hypothesis (1986), when interaction

effects between self-efficacy and goals were observed, they always involved learning instead of performanceapproach goals. Findings of this study suggest that the nature of the goal might not matter as much as its

personal significance or value.

l est largement admis quun sentiment faible dauto-efficacite a un impact negatif sur le fonctionnement et le

rendement de la personne quand elle est tre`s preoccupee par des buts de performance, mais pas si elle

lest par des buts dapprentissage (Dweck, 1986). Cependant, autant les etudes de type correlationnel

quexperimental rapportent des resultats divergents. Comme ces etudes nont examine que peu dindices du

fonctionnement cognitif des personnes, elles nont peut-etre pas reussi a` detecter les aspects sensibles a` limpact

negatif de la combinaison des buts de performance et dun sentiment faible dauto-efficacite. Un autre proble`me

concerne labsence de distinction du type de but de performance examine dans la plupart de ces etudes, en

particulier le but de performance-evitement versus celui de performance-approche. Dans la presente etude, nous

avons centre notre interet sur le but de performance-approche et sur celui dapprentissage afin dexaminer

comment le sentiment dauto-efficacite intervient dans leurs effets sur lautoregulation et la performance dans

une tache cognitive. Cent quarante sujets (85 femmes et 55 hommes) ont participe a` letude. Les sujets ont ete

assignes aleatoirement a` un but dapprentissage ou de performance-approche. Dans chaque condition, un

sentiment dauto-efficacite faible ou eleve devant la tache a aussi ete induit chez la moitie des sujets avant que la

tache soit executee a` voix haute. Lexamen des protocoles verbaux des sujets, lobservation directe de certains de

leurs comportements durant la tache et leurs reponses a` un questionnaire retrospectif ont permis devaluer leur

autoregulation et leur performance. Comme lont montre de nombreuses etudes, lauto-efficacite influence

plusieurs aspects de lautoregulation et de la performance. Contrairement a` lhypothe`se de Dweck (1986), les

effets dinteraction observes entre le sentiment dauto-efficacite et les buts impliquent les buts dapprentissage et

Correspondence should be addressed to There`se Bouffard PhD, Departement de Psychologie, Universite du Quebec a` Montreal,

C.P.8888, Succ. centre-ville, Montreal, Qc, Canada, H3C 3P8 (e-mail: bouffard.therese@uqam.ca).

This study was supported by a grant from The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The authors thank the

anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this paper.

# 2005 International Union of Psychological Science

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/pp/00207594.html

DOI: 10.1080/00207590444000302

374

BOUFFARD ET AL.

non ceux de performance-approche. Les donnees de cette etude sugge`rent que ce nest peut-etre pas tant le type de

but qui importe que sa valeur ou la signification quil revet aux yeux de la personne.

e ha admitido que la autoeficacia baja impacta en detrimento del funcionamiento y el desempeno de una

persona principalmente si persigue metas de rendimiento, pero que no tiene impacto si la persona persigue

metas de aprendizaje (Dweck, 1986). Sin embargo, los resultados tanto de estudios de correlacion como experimentales difieren entre s. Dado que estos estudios examinaban unos cuantos indicadores del funcionamiento

cognitivo de los participantes, tal vez no detectaron aquellos aspectos mas vulnerables al impacto negativo de la

combinacion de metas de rendimiento y la autoeficacia baja. Otra preocupacion es que la mayora de los estudios

no distingua el tipo de metas de rendimiento examinadas, particularmente la meta de rendimiento-evitacion

versus rendimiento-aproximacion. El presente estudio se centro en las metas de rendimiento-aproximacion y de

aprendizaje para examinar como la autoeficacia interviene en sus efectos sobre la autorregulacion y desempeno

de los participantes en una tarea cognitiva. Se examino a 140 participantes (85 mujeres y 55 varones). Los

participantes se haban asignado en forma aleatoria, ya sea a la condicion con metas de aprendizaje o a una con

metas de ejecucion-aproximacion. En cada condicion, la mitad de los participantes reciban retroinformacion

orientada a inducir ya sea creencias de autoeficacia baja o alta, con respecto a la tarea antes de ejecutarla en voz

alta. El examen de los informes verbales de los participantes, la observacion directa de algunas de sus conductas

durante la tarea y las respuestas a un cuestionario retrospectivo permitieron evaluar varios indicadores de su

autorregulacion y desempeno. Como ya lo han informado muchos estudios, la autoeficacia influyo sobre varios

aspectos de la autorregulacion y el desempeno de los participantes. Sin embargo, contrariamente a la hipotesis de

Dweck (1986), cuando se observaron los efectos de la interaccion entre la autoeficacia y las metas, estos siempre

entranaban la meta de aprendizaje en vez de la de rendimiento-aproximacion. Los hallazgos de este estudio

sugieren que la naturaleza de la meta podra no importar tanto como su significado o valor personal.

Recent intentional or goal-oriented theories of

achievement motivation propose that the specific

type of goals adopted by students determines their

choices, attitudes, and performance in achievement situations. Although researchers have given

different labels to these types of goals, two large

classes have been identified in the literature:

learning or task goals and performance, ability,

or ego goals (Ames & Archer, 1988; Dweck, 1986;

Nicholls, 1984).

The contrast between learning and performance

goals bears on what a person is seeking to achieve

and how she values learning processes and the role

of effort. A person striving for learning goals in a

task is mainly concerned with personal development and the acquisition of new skills and knowledge. Learning processes and effort expenditure

are positively valued, and errors are not seen as

threatening but act as a spur to perseverance. A

person striving for performance goals is mainly

concerned with documenting and gaining favourable judgments or avoiding negative judgments

of his or her own ability. Achieving success

with low effort and outperforming others are

seen as requisite conditions towards feeling and

appearing competent. Errors and failures are

threatening because they are seen as evidence of

incompetence.

The types of superordinate goals pursued by

students are important because they elicit qualitatively different motivational patterns and contribute

to deliberate self-regulation in academic tasks

(Ames & Archer, 1988; Bandura, 1986; Dweck,

1986, 1991; Elliott & Dweck, 1988; Fisher & Ford,

1998; Pintrich & Schrauben, 1992). Many researchers maintain that learning goals are adaptive

for cognitive functioning (Archer, 1994; Bell &

Zozlowski, 2002; Dweck, 1989; Jacacinski, Madden,

& Reider, 2001) and that performance goals may

lead to less positive patterns of motivation, selfregulation, and performance, particularly when

they are combined with low self-efficacy or low

perceived ability (Ames & Archer, 1988; Archer,

1994; Dweck, 1986; Dweck & Leggett, 1988).

According to this hypothesis, when a person is

mainly concerned with showing high competence in

a task, beliefs of inefficacy or low perceived ability

with regard to the task will have a detrimental

impact on his or her functioning and performance.

This negative impact would be due to the persons

belief about the usefulness of effort and its

connotation with low competence, particularly

when the risk of failure is high. However, when a

person is mainly concerned with learning and

personal improvement, and believes that efforts

are a valuable means to improvement, perceived

ability should have no impact whatsoever. The

validity of this hypothesis is widely acknowledged

(Archer, 1994; Dweck, 1986; Dweck & Leggett,

1988; Hofmann, 1993; Midgley, 1993; Schmidt &

Ford, 2003), but there are as of yet few empirical

studies that have tested it.

SELF-EFFICACY AND ACHIEVEMENT GOALS

Correlational studies examining how levels of

perceived competence intervene in the effect of

achievement goals on task motivation and performance in school settings did not provide clear

evidence. In some cases, studies reported confirmation of the hypothesis in a given class but not

in the other (Goudas, Biddle, & Fox, 1994; Kaplan

& Midgley, 1997). Even when they distinguished

performance-approach and work avoidance goals,

Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, Carter, and Elliot

(2000) still failed to find evidence that perceived

competence moderates the effect of any of these

goals. Other studies reported even more controversial conclusions. Harackiewicz, Barron, Carter,

Lehto, and Elliot (1997) and Miller, Behrens,

Greene, and Newman (1993) found that low rather

than high perceived competence was more adaptive for students with performance goals. Miller,

Greene, Montalvo, Ravindran, and Nichols (1996)

reported that having high self-efficacy was more

beneficial for students with low performance goals.

Finally, in other studies it was students with

learning goals who were negatively affected by low

self-efficacy beliefs (Kaplan & Midgley, 1997;

Miller et al. 1996; Vezeau, Bouffard, & Tetreault,

1997).

Divergent conclusions are also reported in

experimental studies that have tested whether

self-efficacy has a detrimental effect when the

person is strongly committed to performance goals

(Cury, Biddle, Sarrazin, & Famose, 1997; Elliott &

Dweck, 1988; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996;

Johnson, Perlow, & Pieper, 1993). Thus, even

under controlled conditions, the hypothesis still

lacks empirical evidence. However, these studies

examined very few indicators of participants

cognitive functioning, thus they may have failed

to detect those aspects that could be more vulnerable to a negative impact of the combination of

performance goals and low self-efficacy. Another

concern is the type of performance goal induced.

According to Harackiewicz (Harackiewicz,

Barron, & Elliot, 1998; Harackiewicz et al.,

2000), there was a conceptual ambiguity in the

early definitions of performance goals: They

sometimes focused on gaining positive judgments

of competence, or on avoiding unfavourable

judgments of competence, or, worse, on both at

a same time. The former type of performance goal

is now called a performance-approach goal

whereas the second is called performance-avoidance. Recently, authors showed that performanceapproach goals emphasizing students pursuit and

achievement of high standards to gain positive

judgments of competence tend to foster academic

achievement (Bouffard, Boileau, & Vezeau, 2001;

375

Bouffard & Couture, 2003; Church, Elliot, &

Gable, 2000; Harackiewicz et al., 1997, 2000).

With few exceptions, studies examining how selfefficacy intervenes in the effects of performance

goals did not distinguish these types of goals, nor

did they provide the items used to assess them.

Thus, it is unclear how the conceptual ambiguity

in performance goals is involved in the diverging

conclusions. Given the potentially adaptive value

of a performance-approach goal, in this study it

was decided to test the hypothesis when this goal

was involved.

The purpose of the present study was to

examine how self-efficacy intervenes in the effects

of learning and of performance-approach goals.

Experimental manipulations were used to induce

either learning or performance-approach goals

and either high or low self-efficacy beliefs with

regard to the task in half the participants in each

goal condition. In order to focus participants

attention on learning goals, the task was presented

as an opportunity to improve vocabulary and

comprehension skills; in order to focus participants attention on the performance-approach

goal, the task was presented as an opportunity

for assessing their verbal competence.

The choice of the verbal concept identification

task (see Bouffard-Bouchard, Parent, & Larivee,

1993, for a description) is based on two important

criteria: Completion of a problem does not provide

information about correctness of the response,

thus the task is suitable for manipulating selfefficacy. The task is also suitable for thinking

aloud during execution, which should allow access

to several covert self-regulatory processes. Direct

observation of participants online self-regulation

during task execution and their answers to retrospective questions will provide additional information about the processes used to solve the task.

Using several indicators of participants functioning should increase the likelihood of observing

whether some of them are affected by the

interaction between goals and self-efficacy beliefs.

METHOD

Participants

The sample comprised 140 college students (85

females and 55 males, mean age 5 17.8 years,

SD 5 8.6 months) recruited via an announcement

in the student newspaper. They were offered $10 as

compensation for coming to the laboratory. Half

of the males and females were randomly assigned

to either the learning or the performance-approach

376

BOUFFARD ET AL.

goal condition, and in each group, half of the

students were randomly assigned to the high or the

low self-efficacy condition.

Procedure

Students were examined during an individual

session that lasted about 45 to 50 minutes. On

arrival at the laboratory, they were informed that

the experiment was aimed at knowing what

students usually do to discover the meaning of

an unknown word when only the sentence context

is available to them. Each problem was comprised

of six different sentences in which the same target

word was replaced by an imaginary word. The

subject had to discover, based on contextual cues,

the single meaningful word that adequately

replaced a nonsense word appearing in all

sentences of the problem. According to the

condition to which they had been assigned,

students received the following information about

the task.

Induction of learning goal

The task comprises problems of varying

difficulty among which one is really difficult.

However, working carefully on problems will

allow you to discover new ways and strategies as

to how solve them. You may encounter difficulties

during the solving process, but this is usual and

normal. The very important thing is to do your

best since this will lead you to improve your

vocabulary and comprehension skills which could

be useful for your learning in class.

Induction of performance-approach goal

The task comprises problems of varying

difficulty among which one is really difficult.

However, since the performance on this task is

linked to verbal IQ, working carefully on problems

will allow you to have information about your

verbal competence. You may encounter difficulties

during the solving process, but this is usual and

normal. The very important thing is to do your

best since this will lead you to get information

about your verbal IQ.

The objective of the task was then explained and

the experimenter executed a sample problem to

familiarize students. As a manipulation check,

students filled out a 10-item questionnaire developed for the purpose of this study (see

Appendix A). Five items assessed performanceapproach goals (I will work as hard as I can to get

the greater number of correct responses) whereas

five others assessed learning goals (The most

important thing to me in this task is to learn new

ways to discover the meaning of new words).

Internal consistency reached .83 and .84 respectively for the learning and the performanceapproach subscales.

Students then had 3 minutes to attempt to solve

each of three problems. They were asked to work

aloud and to report every thought without

selecting those of a specific type, and were advised

that they would be reminded to keep talking if they

seemed to forget to think aloud. Students were

requested to give a response for each problem.

Then, as a function of students assignment to the

self-efficacy conditions, they received the following

feedback about their performance.

High self-efficacy condition

You look to have worked carefully in attempting to solve these problems. You seem to be quite

at ease with this kind of task. As a matter of fact,

your three responses are correct. Usually, students

of your school level really have problems with this

task. In order to know how you compared to

them, look at these graphics that show the

percentage of students of your school level who

succeed at each of these problems.

Low self-efficacy condition

You look to have worked carefully in attempting to solve these problems. You do not seem to be

quite at ease with this kind of task. As a matter of

fact, your three responses are incorrect. Usually,

students of your school level do not really have

problems with this task. In order to know how you

compared to them, look at these graphics that

show the percentage of students of your school

level who succeed at each of these problems.

The graphics were designed to clearly show that

the students performance was outstandingly good

for those in the high self-efficacy condition,

whereas they clearly showed that the students

performance was outstandingly poor for those in

the low self-efficacy condition.

In order to check the manipulation of selfefficacy, students were informed that there were

four remaining problems to solve and that, in

order to help a colleague who was a researcher

interested in how college students could accurately

predict their performance, could they kindly try to

predict their performance on the remaining problems. They were informed that, following the

results of a previous study conducted with students

SELF-EFFICACY AND ACHIEVEMENT GOALS

of their school level, the problems were of varying

difficulty. The difficulty rating of each problem

was indicated. Then, each student received four

sheets of paper, each one corresponding to a

problem. Two questions appeared on each sheet:

The first asked whether the student believed he/she

would resolve the problem, and if yes what was

his/her level of confidence about the expected

success on a scale ranging from very unsure (10%)

to completely sure (100%). The experimenter read

aloud all the sentences of the first problem, after

which the student indicated his/her responses. This

procedure was repeated for each problem.

Exposure to the problems was limited to preclude

students from attempting to solve them prior to

rating their self-efficacy. The experimenter kept

her back to the student to reduce concern over

social evaluation. The students put their answers

in an envelope and sealed it. Internal consistency

for self-efficacy reached .85.

Students were then allowed a 20-minute period

within which to solve the four experimental

problems. As for the previous problems, they were

instructed to work aloud. However, they were now

free to choose the number and sequence of the

problems to be solved as well as whether or not to

give a response. They were permitted to rework

any of the experimental problems for whatever

reason. The only requirement was to not work on

two or more problems at the same time. At the end

of this period, students were given the option to

work for an additional 5 minutes. Those who said

they had finished all problems were offered a last

one to be chosen among one of average or of high

difficulty. Even though a student preferred to

continue working on the preceding problems or

not to do this last problem, he/she was requested

to say which one he/she would have chosen

otherwise. Finally, students were asked the two

following retrospective questions: Before you

started working, I informed you that the fourth

problem was particularly difficult. Which, among

the following alternativeschallenged, indifferent,

discouragedbest characterized how you felt

about this? I observed the sequence in which

you attempted to solve the problems. Was it at

random? (if no) What was your purpose in doing

so?

Given the deception used in this study, all

students were completely debriefed before leaving

the room about the manipulations they had

undergone. They were told that assignments to

either group were made at random and the real

objectives of the study were exposed. It was also

clearly explained to them that the task was nothing

else than a sort of game created for the purposes of

377

the study. It was emphasized that finding

responses was most often a matter of luck or

insight, and that in no way was it related to any

aspect of verbal IQ or intellectual capacity.

The entire session was tape-recorded. In addition, the experimenter directly recorded on an

observational form the number of students

glances at the clock or at a watch, instances of

reworking an already attempted problem, and

students responses to the retrospective questions.

Data codification

Self-regulation is a complex mechanism that

encompasses multiple activities, some of which

are difficult to assess because they are composed of

usually covert processes (Borkowski, Johnson, &

Reid, 1987; Bouffard-Bouchard et al., 1993;

Lefebvre-Pinard & Pinard, 1985). In order to

access multiple self-regulatory components, three

sources of information were used: verbal reports,

direct observation, and retrospective questions.

The practice problems only served to manipulate students self-efficacy and to exercise participants in expressing thoughts aloud. Therefore,

only performances on these problems were examined to verify equivalence of groups at the outset

of the procedure. The verbal reports were transcribed and segmented into units by three independent judges blind to the students classification.

The criterion used for segmentation was that a

stated idea, whether grammatically correct or not,

constituted a unit. Inter-judge agreement on

segmentation reached 91%. The written protocols

were then categorized according to a coding

scheme developed for previous studies that used

the same task and data collection procedure

(Bouffard-Bouchard et al., 1993). Only one coding

category, described below, was allowed per unit.

Inter-judge agreement, calculated on 40% of the

protocols chosen randomly, reached 85%. All

disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Verbal fluency might have been a confounding

factor. Thus, the total number of statements was

counted for each student and used as a covariate in

analyses of data issued from verbal protocols.

Measure of self-regulation

Self-regulation encompasses several different components: a cognitive component comprising strategies and activities required to solve the task; a

metacognitive component comprising strategies

aimed at controlling the solving process as well

as metacognitive experiences expressing thoughts

378

BOUFFARD ET AL.

and feelings about progress toward the goal; and a

motivational component comprising indicators of

students commitment to the task such as expenditure of effort and persistence.

1. Cognitive strategies refer to a students making

use of her/his previous knowledge about

language, like identifying the category to

which the target word belongs (a verb, a

noun, an adjective, etc.), or making use of

the contextual cues of the sentences in which

the word is embedded, etc. (see BouffardBouchard et al., 1993, for a description of

categories).

2. Metacognitive strategies refer to a students

report of supervision activities like monitoring

of processing (Hum, it seems that this word

fits well with five sentences. What could it

mean with the sixth one?), monitoring of

time, as indicated by students instances of

checking the time by glancing at the clock or

at a watch or statements about management

of working time (I already spent too much

time on this one. I will try another one.),

and planning (I better start with the easiest

one).

With regard to the latter category, students

responses to the retrospective question about their

reason for choosing the sequence in which they

attempted to solve problems were also examined;

95% of these responses fell into one of the

following categories: no specific intention (Well,

I did not really choose. I took them from left to

right); self-training or self-encouragement in

starting with the easiest problem (Yes, I thought

that solving the easy one first would boost me for

the others); management of ones cognitive functioning (I thought it was better to attempt the

difficult one first while I was fresh. I thought I

should have enough time and energy for the easiest

ones at the end).

3.

1. Metacognitive experiences refer to the students conscious internal feedback about how

and why they progress (or not) toward the

goal, and they were characterized either by a

positive or a negative valence. Metacognitive

experiences with a positive valence refer to

a students positive thoughts about solving

the problem (I feel I am close to the

solution. I am sure I will find the word),

or self-reinforcements (Good, good, you are

doing very well, lets go). Metacognitive

experiences with a negative valence refer to

self-debilitating thoughts about achieving

the goal or negative self-appraisal of ones

own ability that may interfere with solving

processes (You should not have accepted me

in your study, I am so poor at solving such

problems).

2. Motivation was examined using three indica4.

tors. The first, labelled persistence, was

scored by allowing one point for each

problem the student kept working on until

he/she found a solution (whether it was

correct or not), and one more point for

accepting the extra working time. The second

indicator, called choice of difficulty, refers to

the degree of difficulty students chose for the

additional problem. Finally, the third indicator, called mental attitude, refers to students responses about how they felt when

they were informed about the difficulty of the

fourth problem.

Actual performance was assessed using two

criteria: the number of correct responses and the

number of rejections of ones own correct

responses.

RESULTS

Due to mechanical problems, verbal protocols of

12 students (7 and 5 students respectively in the

performance and the learning condition) were lost.

Therefore, the sample included in the analyses

varied from 128 to 140 students depending on

whether or not measures were issued from verbal

protocols.

Preliminary analyses examined whether or not

goal and self-efficacy manipulations were successful. The analysis of learning and performanceapproach scores using goal condition (62) and

gender (62) as factors showed that learning

goals were higher for students in the learning

condition than for those in performance-approach

condition, F(1, 139) 5 7.79, p , .005, whereas

performance-approach goals were higher for

students in the performance-approach condition than for those in the learning condition,

F(1, 139) 5 14.47, p , .001. There was no gender

effect or interaction.

The number of students positive expectations

about the upcoming problems and the associated

levels of confidence were analysed using selfefficacy condition (62) and gender (62) as

factors. Students in the high self-efficacy condition

reported a greater number of positive expectations, F(1, 139) 5 7.92, p , .005, and higher levels

of confidence, F(1, 139) 5 7.90, p , .005, than

did those in the low condition. There was no

gender effect or interaction. These results confirm

SELF-EFFICACY AND ACHIEVEMENT GOALS

that the goal and self-efficacy manipulations were

successful.

The analysis of students performance on

problems they solved prior to the self-efficacy

manipulation according to goal condition (62),

self-efficacy condition (62), and gender (62) as

factors showed no effect for any factor nor an

interaction effect between factors. The analysis

performed to examine effect of gender on overall

dependent measures showed no difference between

males and females. Therefore, data of males and

females were aggregated in the remaining analyses.

Intercorrelations between cognitive and metacognitive strategies and metacognitive experiences

were also examined. No relation was observed

between metacognitive experiences with a negative

valence and the other measures, and the relations

between monitoring of time and other variables

were low. However, relations between metacognitive experiences with a positive valence, and

cognitive and metacognitive strategies related to

monitoring of processing and to planning ranged

from .40 to .49. Therefore, in order to avoid

problems of collinearity and duplicate analyses, a

global score of self-regulatory statements was

calculated by summing up data on these categories.

Analyses of variance (ANCOVAs) with goal

(62) and self-efficacy (62) conditions as factors

and verbal fluency as a covariate examined data

on self-regulatory statements, negative thoughts,

and monitoring of time. Since the covariate was

irrelevant for persistence and performance, it was

379

omitted (see Table 1 for means and standard

deviations). Because data on order of solving

problems, mental attitude, and choice of difficulty

were dichotomous, they were examined using Chisquare analyses controlling for each factor successively. Also, given the theoretical importance of

potential interaction between self-efficacy and

goal, marginal effect (p , .10) was further explored.

Results of the analysis on self-regulatory statements showed significant effects for the covariate,

F(1, 123) 5 18.11, p , .001, and for goal condition, F(1,123) 5 4.53, p , .05, but no effect for

self-efficacy, nor for the interaction between

factors. Whatever their self-efficacy condition,

students assigned to the learning condition (M 5

10.0) expressed more self-regulatory statements

than did those in the performance-approach

condition (M 5 6.0).

The analysis of metacognitive experiences with a

negative valence showed that students assigned

to the low self-efficacy condition (M 5 0.41)

expressed them almost twice as often than did

those assigned to the high self-efficacy condition

(M 5 0.22), F(1, 123) 5 3.05, p , .05. No effect

was found for the covariate, for goal condition, or

for the interaction between factors.

With regard to monitoring of time, significant

effects were found for the covariate, F(1, 123) 5

5.50, p , .05, and for self-efficacy, F(1, 123) 5

3.84, p , .05, as well as a marginally significant

effect for the interaction between self-efficacy and

goal condition F(1, 123) 5 3.75, p , .06. While

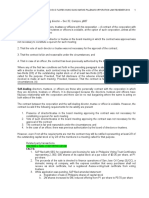

TABLE 1

Means (and standard deviations) of self-regulatory and performance measures according to goal and self-efficacy conditions

Goals

Performance-approach

Self-regulatory measures

Self-regulatory statements

Metacognitive experiences with a negative valence

Monitoring of time

Persistencea

Performance measures

Rejection of correct responsesa

Correct reponsesa

Learning

High SE

(n 5 30)

Low SE

(n 5 32)

High SE

(n 5 35)

Low SE

(n 5 31)

6.50

(8.45)

0.20

(0.38)

1.85

(1.58)

5.55

(1.14)

5.59

(8.48)

0.38

(0.48)

1.64

(2.01)

5.28

(1.89)

10.94

(11.50)

0.26

(0.40)

2.32

(1.47)

5.57

(0.69)

9.00

(8.44)

0.55

(0.65)

1.30

(1.29)

4.74

(1.73)

0.09

(0.29)

1.73

(0.83)

0.39

(0.68)

1.53

(0.91)

0.03

(0.16)

1.97

(0.72)

0.56

(0.56)

1.27

(1.02)

a

Cell sizes of variables comprising the entire sample: (n 5 33) (n 5 36) (n 5 37) (n 5 34).

SE 5 self-efficacy.

380

BOUFFARD ET AL.

students in the performance-approach condition

did not differ according to self-efficacy (M 5 1.7

for both groups), students in the learning condition who were assigned to the high self-efficacy

condition (M 5 2.3) expressed concerns about

monitoring their working time (either verbally or

behaviourally) more often than did those in the

low self-efficacy condition (M 5 1.3).

Analysis of persistence showed an effect of selfefficacy, F(1, 136) 5 5.15, p , .05, and a marginal

effect of the interaction between factors, F(1, 136)

5 2.95, p , .09. Persistence of students in the

performance-approach condition did not differ

according to self-efficacy, but students in the

learning condition who were assigned to the high

self-efficacy condition tended to persist longer

than those in the low self-efficacy condition.

Students reasons for solving problems in a

given sequence varied according to self-efficacy

and goal condition. In the performance-approach

condition, the proportion of students reporting

either reason did not differ whatever their selfefficacy condition. However, in the learning

condition, differences were found according to

self-efficacy, x2(2) 5 6.143, p , .05. Concerns

about managing their working time or cognitive

function were reported by students in both the low

and high self-efficacy condition (21% and 45%

respectively). Concerns about self-training or selfencouragement were reported by 50% and 24% of

students respectively in the low and high selfefficacy conditions. The proportion of students

reporting that they had no specific intention was

similar whatever the self-efficacy or the goal

condition.

With respect to students mental attitude about

the presence of a very difficult problem, the

proportion of those reporting discouragement

and challenge differed according to self-efficacy

conditions in both the learning, x2(2) 5 10.33,

p , .005, and the performance-approach, x2(2) 5

17.45, p , .001, goal condition. In the high selfefficacy condition, only 2% of students in the

performance-approach condition and no students

in the learning condition expressed discouragement compared to 36% and 25% of those in the

low self-efficacy condition. In the high self-efficacy

condition, 73% and 64% of students in the

performance-approach and learning condition

respectively reported challenge against 29% and

39% of students in the low self-efficacy condition.

Similar analyses performed while controlling for

self-efficacy showed no difference between goal

conditions. The proportion of students reporting

they remained indifferent about the difficulty of a

given problem was similar whatever the selfefficacy or the goal condition.

The analysis of the level of difficulty of the extra

problem selected by students showed differences

according to self-efficacy. In both the learning,

x2(1) 5 10.52, p , .001, and the performanceapproach, x2(1) 5 4.32, p , .05, goal condition,

the proportion of students saying they would

choose (or did choose) a more difficult problem

was higher in the high self-efficacy condition (66%

and 54% respectively in the performance-approach

and the learning condition) than it was in the low

self-efficacy condition (27% and 29% respectively

in the performance-approach and the learning

condition). Again, similar analyses performed

controlling for self-efficacy showed no difference

between goal conditions.

Finally, a multivariate analysis of variance

performed on students actual performance using

goal (62) and self-efficacy (62) conditions as

factors revealed an effect for self-efficacy, F(2, 135)

5 13.43, p , .001. Subsequent univariate analyses

showed that students in the high self-efficacy

condition less often (M 5 0.06) rejected correct

responses, F(1, 136) 5 23.61, p , .001, than did

those in the low self-efficacy condition (M 5 0.47),

and that they also obtained a greater number

of correct responses, F(1, 136) 5 9.31, p , .005

(M 5 1.86 and M 5 1.40 respectively in the high

and low self-efficacy condition). However, this

latter effect was qualified by a marginal interaction

between self-efficacy and goal condition, F(1, 136)

5 2.93, p , .10. While students in the performance-approach condition did not differ according to self-efficacy (M 5 1.53 and M 5 1.73

respectively for low and high self-efficacy), students in the high self-efficacy condition reached a

greater number of correct responses (M 5 1.97)

than those in the low condition (M 5 1.27), F(1,

69) 5 11.44, p , .001.

DISCUSSION

This study was aimed at examining the hypothesis

stating that self-efficacy intervenes in the effect of

goals on students cognitive functioning and

performance. Following this hypothesis, whatever

a students self-efficacy beliefs, endorsing learning

goals will led him/her to adaptive patterns of

functioning. However, self-efficacy will make a

difference for a student endorsing performance

goals. More precisely, while adaptive patterns of

functioning should be expected when a student has

high self-efficacy beliefs, the reverse should be

expected when he/she has low self-efficacy beliefs.

SELF-EFFICACY AND ACHIEVEMENT GOALS

In order to avoid confounding different types of

performance goals, it was decided to test the

hypothesis when a performance-approach goal

was involved. High and low self-efficacy beliefs

as well as learning and performance-approach

goals were experimentally induced. Manipulation

checks confirmed that self-efficacy and goals had

been induced successfully. In addition, the experimental task was carefully selected to allow for

observation of a greater number of indices of

students self-regulation, reactions, and performance than had been done in previous studies

examining the hypothesis under investigation.

Seven indicators of participants online selfregulation related to cognitive, metacognitive,

and motivational processes were examined, as well

as two dimensions of their actual performance.

Self-efficacy was found to influence various

aspects of students functioning. Those in the low

self-efficacy group expressed more instances of

negative metacognitive experiences than those in

the high self-efficacy group. While the majority of

students in the latter group reported a sense of

challenge when informed about the presence of a

difficult problem, it was the reverse in the former

group. Given the opportunity to choose the level

of difficulty of an extra problem, a majority of

students in the high self-efficacy group but a

minority in the low group said they would like to

attempt to solve a difficult one. Finally, low selfefficacy students more often rejected their own

correct responses and as a consequence, in the

learning condition, had a lower performance than

participants in the high group. In fact, after adding

scores of rejected correct responses to performance, no difference remained between selfefficacy groups in this condition.

Altogether, these findings support the claim by

Bandura and Locke (2003) about the adaptive and

central role of self-efficacy in human functioning.

They replicate the findings reported in various

studies in very different domains such as education

(Bouffard & Couture, 2003; Lee & Klein, 2002;

Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2003; Pajares, 2003;

Schunk, 1990; Zimmerman, Bandura, &

Martinez-Pons, 1992), sports (Feltz, 1988), career

counselling (Hackett, 1995; Lent, Brown, &

Hackett, 1994), organizational psychology (Gist

& Mitchell, 1992; Sadri & Robertson, 1993), or

complex decision-making and problem-solving

(Breland & Donovan, in press; Wood, Bandura,

& Bailey, 1990).

With regard to the hypothesis stating that selfefficacy would intervene in the effect of goals on

students cognitive functioning and performance,

the instances of interaction between self-efficacy

381

and goals all involved learning goals. Other studies

have reported similar conclusions (Kaplan &

Midgley, 1997; Miller et al., 1993, 1996). In the

learning goal condition, when compared to students

in the low self-efficacy condition, those in the high

condition glanced more often at their watch or at

the clock, or expressed comments about working

time allotted during solving the task. This suggests

that they were more concerned about monitoring

their working time, and more active in doing so.

This interpretation is reinforced by their responses

to the retrospective question about the sequence in

which they attempted to solve the problems.

Students in the learning condition were similarly

purposeful in choosing a specific sequence in an

attempt to solve the problems (71% versus 69%

reported a specific reason for having done so), but

their reason differed according to the level of the

induced self-efficacy. Twice as many students in

the high self-efficacy condition than in the low

self-efficacy condition reported that their aim was

managing their working time and energy across

problems. The reverse was observed for those

in the low self-efficacy condition, who instead

reported that their motive was self-training or

self-encouragement. Persistence also differed

between low and high self-efficacy groups within

the learning condition; the former showed less

persistence than the latter. With regard to actual

performance at the task, again students in the

learning condition differed according to selfefficacy; those in the high condition outperformed

those in the low condition. No evidence was found

that students in the performance-approach condition were affected by induced self-efficacy.

Different interpretations may be raised to explain

our results. Since individuals already possess a

dispositional goal orientation, it may be argued

that experimental manipulation leads to different

results according to the initial disposition. Although

it is difficult to eliminate this argument, measurement of the induced goals ensured that the

experimental manipulation was successful. Beyond

this, previous studies have shown that independent

of the link between dispositional goal orientation

and some variables, situational goal orientation has

unique and significant relations with these same

variables (Kozlowski, Gully, Brown, Salas, Smith,

& Nason, 2001).

Alternatively, it may be argued that the manipulation of goals encompassed different incentives

with regard to the importance of achieving the task

at hand. More precisely, the performanceapproach goal was induced by informing students

that task performance was linked to verbal IQ and

that working carefully on problems would allow

382

BOUFFARD ET AL.

them to gain information about it. Even though

students in the low self-efficacy group were

informed they had done poorly on the first

problems and subsequently reported low selfefficacy beliefs for the remaining problems, they

may have considered that they could work harder

and achieve a more positive demonstration of their

verbal competence. In such a case, the importance

of performing at their best may have alleviated the

expected negative impact of low self-efficacy. As

observed, whatever their self-efficacy, students in

the performance-approach condition were similarly active in monitoring their working time,

showed similar persistence, and finally achieved a

similar performance. In comparison, students in

the learning condition were told that working

carefully on problems would allow them to

improve their comprehension skills and vocabulary, which could be useful for their learning in

class. The importance of improving learning skills

may have been insufficient to compensate for the

effects of low self-efficacy. Thus, we argue that

the personal significance or value of a goal may

be more important than its nature per se.

Harackiewicz and Sansone (1991) have already

suggested that competence valuation reflecting the

degree to which a person is concerned with doing

well might sometimes have more effect on task

engagement than perceived competence. Bouffard,

Boisvert, Vezeau, and Larouche (1995) also argue

that because doing the best one can is central to

both those who are strongly concerned with

improving their competence and with getting to

the highest possible level, similar task engagement

should be expected. Being strongly motivated to

do the best one is able to may protect the person

against the deleterious effects of low self-efficacy.

Despite being plagued by self-doubts, a person

may be willing to struggle and make significant

efforts in a situation when doing so is likely to

yield important outcomes. For example, if a

student really wants to be admitted to a programme of study requiring high marks in mathematics, he may decide to expend all the effort he

can to reach this goal despite believing that this

domain is difficult for him. Similarly, if he highly

values improving his mathematics skills, he is also

likely to work hard whether he feels efficacious or

not. Conversely, thinking that gaining high marks

in mathematics is unimportant for admittance into

the programme or if he does not care about

improving his mathematics skills, it is unlikely the

student will make the effort if he is already

convinced he lacks the requisite ability.

In conclusion, the studys findings suggest that a

better understanding of the interplay between

achievement goals and self-efficacy beliefs could

be achieved by distinguishing goals according

to their importance and significance for the

person. Exploration of this issue certainly deserves

some research effort and may benefit both selfefficacy and goal-oriented theories of achievement

motivation.

Manuscript received November 2003

Revised manuscript accepted June 2004

REFERENCES

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the

classroom: Students learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80,

260267.

Archer, J. (1994). Achievement goals as a measure of

motivation in university students. Contemporary

Educational Psychology, 19, 430446.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and

action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A., & Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative selfefficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 88, 8799.

Bell, B. S., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2002). Goal

orientation and ability: Interactive effects on selfefficacy, performance and knowledge. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 87, 497505.

Borkowski, J. G., Johnson, M. B., & Reid, M. K. (1987).

Metacognition, motivation, and controlled performance. In S. J. Ceci (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive,

social, and neuropsychological aspects of learning

disabilities, Vol. 2 (pp. 147173). Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Bouffard, T., Boileau, L., & Vezeau, C. (2001). Students

transition from elementary to high school and

changes of the relationship between motivation and

academic performance. European Journal of

Psychology of Education, XVI, 589604.

Bouffard, T., Boisvert, J., Vezeau, C., & Larouche, C.

(1995). The impact of goal orientation on selfregulation and performance among college students.

British Journal of Educational Psychology, 65,

317329.

Bouffard, T., & Couture, N. (2003). Motivational

profile and academic achievement among students

enrolled in different schooling tracks. Educational

Studies, 29, 1938.

Bouffard-Bouchard, T., Parent, S., & Larivee, S. (1993).

Self-regulation of a concept formation task among

average and gifted students. Journal of Experimental

Child Psychology, 56, 115134.

Breland, B. T., & Donovan, J. J. (in press). The role of

state goal orientation in the goal establishment

process. Human Performance.

Church, M. A., Elliot, A. J., & Gable, S. (2000).

Perceptions of classroom context, achievement goals

and achievement outcomes. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 92, 4354.

Cury, F., Biddle, S., Sarrazin, P., & Famose, J. P.

(1997). Achievement goals and perceived ability

predict investment in learning a sport task. British

Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 293309.

SELF-EFFICACY AND ACHIEVEMENT GOALS

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting

learning. American Psychologist, 41, 10401048.

Dweck, C. S. (1989). Motivation. In A. Lesgold &

R. Glaser (Eds.), Foundations for a psychology of

education (pp. 87136). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Dweck, C. S. (1991). Self-theories and goals: Their role

in motivation, personality, and development. In

R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on

motivation, 1990, Vol. 38: Perspectives on motivation

(pp. 139235). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska

Press.

Dweck, C. S., & Legget, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive

approach

to

motivation

and

personality.

Psychological Review, 95, 256273.

Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An

approach to motivation and achievement. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 512.

Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1996). Approach

and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic

motivation: A mediational analysis. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 461475.

Feltz, D. (1988). Self-confidence and sports performance. In K. B. Pandolf (Ed.), Exercise and sport

science reviews, Vol. 16 (pp. 423457). New York:

Macmillan.

Fisher, S. L., & Ford, K. J. (1998). Differential effects of

learner effort and goal orientation on two learning

outcomes. Personnel Psychology, 51, 397420.

Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy:

A theoretical analysis of its determinants and

malleability. Academy of Management Review, 12,

472485.

Goudas, M., Biddle, S., & Fox, K. (1994). Perceived

locus of causality, goal orientations, and perceived

competence in school physical education classes.

British Journal of Educational Psychology, 64,

453463.

Hackett, G. (1995). Self-efficacy in career choice and

development. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self-efficacy in

changing

societies

(pp. 232259).

Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Carter, S. M.,

Lehto, A. T., & Elliot, A. J. (1997). Predictors and

consequences of achievement goals in the college

classroom: Maintaining interest and making the

grade. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

73, 12841295.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., & Elliot, A. J.

(1998). Rethinking achievement goals: When are they

adaptive for college students and why? Educational

Psychologist, 33, 121.

Harachiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M.,

Carter, S. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2000). Short-term and

long-term consequences of achievement goals:

Predicting interest and performance over time.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 316330.

Harackiewicz, J. M., & Sansone, C. (1991). Goals and

intrinsic motivation: You can get there from here.

Advances in motivation and achievement, Vol. 7

(pp. 2149). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Hofmann, D. A. (1993). The influence of goal orientation on task performance: A substantively meaningful suppressor variable. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, 23, 18271846.

Jacacinski, C. M., Madden, J. L., & Reider, M. H.

(2001). The impact of situational and dispositional

383

achievement goals on performance. Human

Performance, 14, 321337.

Johnson, D., Perlow, R., & Pieper, K. F. (1993).

Differences in task performance as a function

of type of feedback: Learning-oriented versus

performance-oriented. Journal of Applied Psychology, 23, 303320.

Kaplan, A., & Midgley, C. (1997). The effect of

achievement goals: Does level of perceived academic

competence make a difference? Contemporary

Education Psychology, 22, 415435.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., Brown, K. G.,

Salas, E., Smith, E. M., & Nason, E. R. (2001).

Effects of training goals and goal orientation traits

on multidimensional training outcomes and performance adaptability. Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Processes, 85, 131.

Lee, S., & Klein, H. J. (2002). Relationships between

conscientiousness, self-efficacy, self-deception, and

learning over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87,

11751182.

Lefebvre-Pinard, M., & Pinard, A. (1985). Taking

charge of ones own cognitive activity: A moderator

of competence. In E. Neimark, R. Delisi &

J. Newman (Eds.), Moderators of competence

(pp. 191211). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates Inc.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994).

Toward a unifying social-cognitive theory of career

and academic interest, choice and performance.

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 79122.

Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of

self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and

learning in the classroom. Reading and Writing

Quarterly, 19, 119137.

Midgley, C. (1993). Motivation and middle level

schools. In M. L. Maehr & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.),

Advances in motivation and achievement: Vol. 8.

Motivation in the adolescent years (pp. 217274).

Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Miller, R. B., Behrens, J. T., Greene, B. A., &

Newman, D. (1993). Goals and perceived ability:

Impact on student valuing, self-regulation and

persistence. Contemporary Educational Psychology,

18, 214.

Miller, R. B., Greene, B. A., Montalvo, G. P.,

Ravindran, B., & Nichols, J. D. (1996).

Engagement in academic work: The role of learning

goals, future consequences, pleasing others, and

perceived

ability.

Contemporary

Educational

Psychology, 21, 388422.

Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Conceptions of ability and

achievement motivation. In R. Ames & C. Ames

(Eds.), Research on motivation in education, Vol. 1

(pp. 3973). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Pajares, F. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and

achievement in writing: A review of the literature.

Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19, 139158.

Pintrich, P. R., & Schrauben, B. (1992). Students

motivational beliefs and their cognitive engagement

in classroom academic tasks. In D. H. Schunk &

J. L. Meece (Eds.), Student perceptions in the classroom (pp. 149183). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Sadri, G., & Robertson, I. T. (1993). Self-efficacy and

work-related behaviour: A review and meta-analysis.

384

BOUFFARD ET AL.

Applied Psychology: An International Review, 42,

139152.

Schmidt, A. M., & Ford, J. K. (2003). Learning within a

learner control training environment: The interactive

effects of goal orientation and metacognitive instruction on learning outcomes. Personnel Psychology, 56,

405419.

Schunk, D. H. (1990). Goal setting and self-efficacy

during

self-regulated

learning.

Educational

Psychologist, 25, 7186.

Vezeau, C., Bouffard, T., & Tetreault, F. (1997). Impact

du type de buts et du sentiment dauto-efficacite sur

lautoregulation et la performance dans une tache

cognitive [Impact of types of goal and self-efficacy on

self-regulation and performance in a cognitive task].

International Journal of Psychology, 32, 114.

Wood, R., Bandura, A., & Bailey, T. (1990).

Mechanisms governing organizational performance

in complex-making environments. Organizational

Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 46, 181201.

Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M.

(1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The

role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting.

American Educational Research Journal, 29, 663676.

APPENDIX A

Goals questionnaire

L:

PA:

L:

L:

PA:

PA:

L:

PA:

PA:

L:

The most important thing to me in this task is to learn new ways to discover the meaning of new words.

The most important to me is to be among those who will discover the greater number of correct responses.

I will work as hard as I can to discover and master new skills to improve my vocabulary.

I hope that working on this task will allow me to discover things I do not know yet.

The most interesting to me in this task is to know how many correct responses I will find.

My main objective will be to class myself in the very best at this task.

I hope to have the feeling of having learned new things when I will have finished the task.

It is important to me to outperform others in this task.

I will work as hard as I can to get the greater number of correct responses.

Gaining new knowledge and skills is my main objective in this task.

L 5 Learning; PA 5 Performance-approach.

For each item, students must specify their level of agreement on a scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (completely agree).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Government Procurement Reform Act SummaryDocument24 pagesGovernment Procurement Reform Act SummaryAnonymous Q0KzFR2i0% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Jurisprudence On Human Trafficking - Research SJDHSJDHDFDocument3 pagesJurisprudence On Human Trafficking - Research SJDHSJDHDFLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Strictly Privileged and Confidential: MemorandumDocument3 pagesStrictly Privileged and Confidential: MemorandumLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- BarangayS in General TriasDocument2 pagesBarangayS in General TriasLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Nature Is A WhoreDocument1 pageNature Is A WhoreLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- 43) Calaagan Golf Club vs. Sixto ClementeDocument2 pages43) Calaagan Golf Club vs. Sixto ClementeLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- A) CIR Vs Sony PhilippinesDocument2 pagesA) CIR Vs Sony PhilippinesLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- E. CIR vs. Mirant (Phils) Operations CorporationDocument2 pagesE. CIR vs. Mirant (Phils) Operations CorporationLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- 19) Advance Paper Vs ArmaDocument2 pages19) Advance Paper Vs ArmaLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- BibliographyDocument2 pagesBibliographyLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Major Scale Modes Three Notes Per StringDocument1 pageMajor Scale Modes Three Notes Per StringLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- 6) Ty Vs Filipinas Compania de SegurosDocument1 page6) Ty Vs Filipinas Compania de SegurosLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Affidavit of LossDocument2 pagesAffidavit of LossLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- Olives, Lanz Aidan L. Olives 31 March 2016 11382597 Special Proceedings Reflection PaperDocument3 pagesOlives, Lanz Aidan L. Olives 31 March 2016 11382597 Special Proceedings Reflection PaperLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- Part IX EMPLOYER LOCKOUTDocument6 pagesPart IX EMPLOYER LOCKOUTLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Complaint For Support SampleDocument6 pagesComplaint For Support SampleLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Olives Week 1 DigestDocument8 pagesOlives Week 1 DigestLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Garcia Vs Drilon (Petitioner and SC)Document3 pagesGarcia Vs Drilon (Petitioner and SC)Lanz Olives80% (5)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Olives Labor Law Reflection PaperDocument5 pagesOlives Labor Law Reflection PaperLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Real Estate Loan AgreementDocument4 pagesReal Estate Loan AgreementLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- 1) Public Company - Rule 3.1 (M)Document6 pages1) Public Company - Rule 3.1 (M)Lanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- CLFR Nov 29 FinalDocument197 pagesCLFR Nov 29 FinalLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Conclusion Draft Why Should We Not Join TPPDocument2 pagesConclusion Draft Why Should We Not Join TPPLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Legal Writing Course OverviewDocument11 pagesAdvanced Legal Writing Course OverviewLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- RemindersDocument9 pagesRemindersLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- SSS VsDocument2 pagesSSS VsLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Olives, Lanz Aidan L. Olives 31 March 2016 11382597 Special Proceedings Reflection PaperDocument3 pagesOlives, Lanz Aidan L. Olives 31 March 2016 11382597 Special Proceedings Reflection PaperLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- RemindersDocument9 pagesRemindersLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- Mariwasa union registration upheldDocument3 pagesMariwasa union registration upheldLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- CIR Wins Tax Remedies CasesDocument37 pagesCIR Wins Tax Remedies CasesLanz OlivesPas encore d'évaluation

- ADEC - International Community Branch 2016-2017Document23 pagesADEC - International Community Branch 2016-2017Edarabia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- AP Psychology Mnomonic DevicesDocument7 pagesAP Psychology Mnomonic DevicesBellony SandersPas encore d'évaluation

- Eln402 Assess 1Document17 pagesEln402 Assess 1api-3546316120% (2)

- Reading and Writing 4 Q: Skills For Success Unit 4 Student Book Answer KeyDocument3 pagesReading and Writing 4 Q: Skills For Success Unit 4 Student Book Answer KeyPoornachandra50% (2)

- Booklet Inglés Convers - IV Ok (28julio 2014)Document36 pagesBooklet Inglés Convers - IV Ok (28julio 2014)calamandro saezPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis Pengambilan Keputusan Konsumen Dan: Brandpositioning Kopi Instan Di Kota SurakartaDocument12 pagesAnalisis Pengambilan Keputusan Konsumen Dan: Brandpositioning Kopi Instan Di Kota SurakartaRachelMargarethaGultomPas encore d'évaluation

- IPT - Information Processing TheoryDocument6 pagesIPT - Information Processing TheoryCarl LibatiquePas encore d'évaluation

- 1.2.6 - Risk in Outdoor ExperiencesDocument6 pages1.2.6 - Risk in Outdoor ExperiencesMatthew Pringle100% (1)

- The Good of Children and SocietyDocument285 pagesThe Good of Children and SocietyHuzeyfe GültekinPas encore d'évaluation

- A World Leading Hypnosis School - Hypnotherapy Training InstituteDocument6 pagesA World Leading Hypnosis School - Hypnotherapy Training InstituteSAMUELPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Nature of Educational PsychologyDocument44 pagesNature of Educational Psychologypintupal2008100% (8)

- Transdiagnostic CBT For Eating Disorders "CBT-E": Christopher G FairburnDocument100 pagesTransdiagnostic CBT For Eating Disorders "CBT-E": Christopher G FairburnValentina Manzat100% (1)

- Lesson 1 FinalsDocument5 pagesLesson 1 FinalsJannah Grace Antiporta Abrantes100% (1)

- 12 Figley Helping Traumatized FamiliesDocument30 pages12 Figley Helping Traumatized FamiliesHakan KarşılarPas encore d'évaluation

- Life and Work of Saadat Hasan MantoDocument9 pagesLife and Work of Saadat Hasan MantoMuhammad Junaid SialPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL in Making ConclusionDocument6 pagesDLL in Making ConclusionAnonymous pLT15rHQXPas encore d'évaluation

- TPSC Field Report Writing GuidelineDocument7 pagesTPSC Field Report Writing GuidelineJackson Logo'sPas encore d'évaluation

- Nurjannah's PaperDocument16 pagesNurjannah's PaperNurjannaHamzahAbuBakarPas encore d'évaluation

- ResearchDocument41 pagesResearchAngel82% (11)

- Herbert Gans On LevittownDocument2 pagesHerbert Gans On LevittownAnastasiia Sin'kovaPas encore d'évaluation

- Junior Training Sheet - Template - V6.3Document39 pagesJunior Training Sheet - Template - V6.3Rishant MPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of Terms: Maed-FilipinoDocument14 pagesDefinition of Terms: Maed-FilipinoMarceline Ruiz0% (1)

- Design Rules For Additive ManufacturingDocument10 pagesDesign Rules For Additive ManufacturingKazalzs KramPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Baby ThesisDocument43 pagesFinal Baby ThesisCrystal Fabriga AquinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Bullying To The Mental Health of StudentsDocument40 pagesEffects of Bullying To The Mental Health of Students葉Este100% (8)

- Sample Chapter - The Ultimate EU Test Book 2013 Administrator (AD) Edition - FreeDocument31 pagesSample Chapter - The Ultimate EU Test Book 2013 Administrator (AD) Edition - FreeAndras Baneth0% (2)

- Disabilities in SchoolsDocument8 pagesDisabilities in Schoolsapi-286330212Pas encore d'évaluation

- The North American Book of the Dead Part IIDocument11 pagesThe North American Book of the Dead Part IIDean InksterPas encore d'évaluation

- Scholarly Article About Social Studies Education PDFDocument4 pagesScholarly Article About Social Studies Education PDFJoy AlcantaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Chet Holmes - UBMS WorkbookDocument250 pagesChet Holmes - UBMS WorkbookNguyễn Hoàng Bảo100% (12)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityD'EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsD'EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionD'EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (402)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeD'EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BePas encore d'évaluation

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedD'EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (78)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementD'EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (40)