Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Clanak Nije Moje Vlasništvo, Postavljam Ga Kakobih Mogla Skinuti PDF Koji Mi Treba, Unaprijed Se Ispričavam

Transféré par

tinaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Clanak Nije Moje Vlasništvo, Postavljam Ga Kakobih Mogla Skinuti PDF Koji Mi Treba, Unaprijed Se Ispričavam

Transféré par

tinaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

After-School Activities and Leisure

Education

28

Jaume Trilla, Ana Ayuste, and Ingrid Agud

28.1

Introduction

Robert Louis Stevenson, the author of stories that have filled the leisure time of

many readers both adult and child alike, wrote an essay in 1887 suggestively

entitled An Apology for Idlers which defended the virtues, including those in

the educational sphere, of idleness. He offered the following dialogue between an

upstanding citizen and a boy who, during school hours, was lying under the linden

trees on the bank of a stream:

How now, young fellow, what dost thou here?

Truly, sir, I take mine ease.

Is not this the hour of the class? And shouldst thou not be plying thy Book with diligence,

to the end thou mayest obtain knowledge?

Nay, but this also I follow after Learning, by your leave.

Learning, quotha! After what fashion, I pray thee? Is it mathematics?

No, to be sure.

Is it metaphysics?

Nor that.

Is it some language?

Nay, it is no language.

Is it a trade?

Nor a trade neither.

Why, then, what ist?

Indeed, sir, as a time may soon come for me to go upon Pilgrimage, I am desirous to note

what is commonly done by persons in my case, and where are the ugliest Sloughs and

Thickets on the Road; as also, what manner of Staff is of the best service. Moreover, I lie

here, by this water, to learn by root-of-heart a lesson which my master teaches me to call

Peace, or Contentment. (Stevenson 2009)

J. Trilla (*) A. Ayuste I. Agud

Department of Theory and History of Education, University of Barcelona, Mundet, Campus

Mundet, Llevant, Barcelona, Spain

e-mail: jtrilla@ub.edu; the@ub.edu

A. Ben-Arieh et al. (eds.), Handbook of Child Well-Being,

863

DOI 10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8_28, # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014

864

J. Trilla et al.

The educational universe during Stevensons time was quite different from that

of today. In addition to the informal education that the boy in the story enjoyed and

flaunted, there was the family, the school (which many were unable to attend), and

a few other educational institutions. Nowadays, at least in developed countries,

schooling is compulsory and many other institutions have emerged with explicit

educational purposes. The educational life of our children is no longer limited to

family, school, and the street. In fact, our children spend many hours in school and

little time in the street (and even less beside a stream). After school many children

attend art workshops on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays or basketball practice

Tuesdays and Thursdays for a game on Saturday or Sunday. Some of those who do

not participate in sports take part in weekend activities at recreational centers or are

members of an organization such as the Boy Scouts. Some children might go to the

neighborhood play center or toy library or regularly attend music school. There are

those whose parents have hired a private tutor because they are doing poorly in

math. In summer, some children go to camp for 2 weeks, and because school

holidays are so long and parents have no idea what to do with their children,

some are enrolled in other extracurricular activities. In a study of a large sample

of children and adolescents in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, we found that

more than three fourths of the subjects regularly participated in extracurricular

activities, and more than one third of the sample also participated in more than one

activity (Trilla and Ros 2005).

This chapter is devoted to the entire range of after-school and free-time education

opportunities which are based on two premises that we assume are widely shared. The

first is that free time is important to the welfare and quality of life of people in general,

including children (Levy 2000; Trilla et al. 2001). The second premise is that previous

education influences how a person uses their free time. As expressed, these premises

are hardly debatable. However, while their theoretical and generic formulation may be

generally accepted, there are many significant issues that are far less clear when trying

to specify the premises in more exact terms or when trying to act on them. Do all uses

of free time contribute to the welfare of people and the community? Are some leisure

activities humanly and socially more desirable than others? If so, which ones? Finding

an answer to this question is necessary when addressing the second premise from an

educational perspective. For example, how can education help children enjoy qualitatively better leisure time? What free-time educational institutions, programs, and

resources currently exist and what others should exist? These are the questions we

explore in this chapter.

This chapter is divided into three parts. The first section deals with conceptual

issues related to free time and leisure and their application with respect to children.

The second section discusses the relationship between education and free/leisure

time. It begins by considering the justification for educational intervention into

childrens free time, based on an analysis of values and countervalues of educational intervention. Subsequently, the various aspects of what we call the pedagogy of leisure (education in, for, and through free time) are systematized. We also

devote part of this second section to identifying the factors that have influenced the

development of this education sector. The third section presents the various

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

865

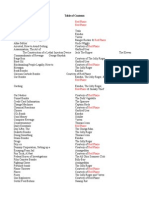

educational environments in which to spend free time, such as institutions, programs, facilities, activities, and resources. These are presented as an index, after

which their shared characteristics are analyzed. Then, in the epilogue, and drawing

on the suggestions offered in Stevensons text, the possible limitations that should

be imposed in the name of childrens welfare on the accumulation of institutionalized educational activities are discussed.

28.2

Free Time and Leisure: Ideas and Realities

28.2.1 The Concept of Free Time

Leisure, free time, and other similar terms such as recreation and idle time

are common expressions whose meanings are clear when they are used colloquially.

When we try to define them rigorously or use them in real situations, however, we

realize that the concepts they represent are not always as clear as they seem. We

devote this first section of the chapter to these conceptual issues and to proposing

certain stipulations that will be useful for the remainder of the chapter.

Initially, the concepts of free time and leisure are usually defined as the opposite

of work. Free time would be the time left once an individual has fulfilled his or her

obligations at work (in the case of adults) or at school (in the case of children).

Nevertheless, it is obvious that not all non-work time (or non-school time) is real

free time. The time allocated to ones basic biological needs and certain family

obligations would not be classified as free time. The formulas normally used for

a rough definition of free time or leisure are shown in Fig. 28.1. This simple outline,

which may be valid as a first approximation, is clearly insufficient when it is used in

an in-depth exploration of the real structure of the time and activities of todays

complex society. In our view, the outline is insufficient for the following three

reasons:

1. Because it is only really applicable in the case of working adults or in-school

children. The outline does not address what free time or leisure represents for

those social groups who do not work or attend school. For example, what is free

time for a prisoner, a sick person, the unemployed, or a child excluded from the

education system? Are these people fortunate to have plenty of non-work time,

or does their particular situation make it difficult for or even deny them the

possibility to truly enjoy leisure? At this point it would be helpful in the

framework of our social-labor context to interpret a consideration made by de

Grazia (2000) when commenting on Aristotles concept of leisure. De Grazia

explains that for a Greek philosopher, the condition for enjoying leisure is not

only to have non-occupied time at ones disposal, but more accurately to be

freed from the need to be busy. In this sense, people who ought to be working but

are unemployed would not be in the best condition to enjoy leisure, despite

having all time in the world at their disposal. Based on this idea, it could be said

that only those who have freed themselves from the need to work for a while

because they have worked before, or those who, as in Aristotles times, did not

866

J. Trilla et al.

Fig. 28.1 Simple outline of

the concepts of free time and

leisure

NON-WORK TIME

WORK TIME

(SCHOOL TIME)

BIOLOGICAL

NEEDS,

FAMILY and

SOCIAL

OBLIGATIONS, etc.

LEISURE

or

FREE TIME

have to work because they had an army of slaves to do it for them, are truly able

to appreciate leisure.

2. The outline is also insufficient because it does not include activities or times

which for certain people have a marked quantitative or qualitative significance.

For the religiously devout, is time devoted to their religious practices free time? Is

time a person dedicates to philanthropic tasks or volunteer work leisure time? The

outline in Fig. 28.1 is overly simplistic, requiring very dissimilar activities to be

placed in the same bag, activities to which people no doubt assign a very different

meaning. The central sector of the outline would have to include a diverse range

of activities all grouped together such as personal hygiene, standing in line to

renew your passport, praying, taking care of children, or carrying out acts of

solidarity. To address this, some authors have introduced other terms or concepts

into the discourse on time which highlight the insufficiency of the simple division

between work and free time or leisure. Concepts such as socially useful time

and idle time (instead of free time) suggest the need to use a more complex and

precise outline than the one proposed in Fig. 28.1.

3. The outline is too simple because it does not provide criteria to distinguish

between free time and leisure. It is true that in everyday language both expressions are used interchangeably. In some cases, however, it may be appropriate to

distinguish them based on the denotative or connotative contents that they both

represent. On the one hand, free time, literally refers to an area or specific type of

overall time, while leisure seems to refer to a type of activity. Free time would

be, so to speak, a container, and leisure would be its possible content.

We therefore propose a more precise model than the previous one, overcoming

some of the limitations mentioned above (Trilla 1993a). In the outline in Fig. 28.2,

we no longer start out from the difference between work and free time or leisure but

from two more general, clearer categories that we call available time and

nonavailable time. These categories are explained in more detail below, but, in

short, nonavailable time is that which individuals have committed to tasks that

cannot be avoided. It is time usually governed by external forces, dictated by

inescapable obligations according to the status of the individual. Available time

would be that which remains.

Nonavailable time can be divided into the time spent directly or indirectly by

work (or school for children) and the time occupied by what we call non-work

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

867

Professional work (or school)

Work (or

school)

Housework

Outside-work (or extra-curricular)

activities

Basic biological needs

Non-available

Non-work

obligations

Family obligations

Social obligations

TIME

Religious activities

Self-imposed

social

occupations

Social volunteering activities

Other institutionalised training activities

Available

Non-autotelic personal occupations.

Free time

Sterile free time

Leisure

(J. Trilla)

Fig. 28.2 Complex outline of free time and leisure

obligations. In the first case, we have paid work or housework and the time spent on

work-associated or school-associated activities such as travelling or homework.

In the non-work obligations category we include basic biological needs: sleep,

personal hygiene, and eating. We call them basic because when the time taken for

such needs exceeds the strictly necessary minimum, or when we add another

dimension to those activities, they acquire an additional significance (or even

a different substantive significance) which would place them in another category.

Sleeping-in on a Sunday morning just for pleasure or a meal where gastronomic or

social enjoyment are the main motivations would be activities closer to leisure than

to the nonavailable time category. The second non-work obligation is family

obligations such as looking after children, and the third is social, administrative,

and bureaucratic obligations such as completing income tax returns.

After discounting these times, there is some time left that we can use with much

greater discretion. This is what we call available time. Available time also has two

subcategories: the time for self-imposed social occupation and genuine free time.

The difference between the two is that for the first type we make a commitment,

albeit independently and voluntarily, with an authority beyond our control.

Examples of self-imposed social occupations would be certain religious activities,

voluntary activities with social purposes (volunteering in the strict sense of the

word, political affiliation, trade-union membership), and institutionalized training

activities. In these latter activities we do not include the formal schooling of

children since for them this would be comparable to adult professional work.

868

J. Trilla et al.

In all these cases, the commitment is acquired voluntarily, but until the individual

decides to end it, his or her decisions will be determined by others. The difference

between self-imposed social occupations and genuine free time is often very subtle

but can be illustrated with examples. An individual can decide to devote time to

reading poetry on a daily basis, but if one day he fails to do so he does not have

explain it to anyone since he has not established any external commitment. However, if a young person, with the same autonomy, decides to dedicate every

Saturday afternoon to being a child-group facilitator, he makes a commitment to

an external body. Therefore, if he does not show up on Saturday, he should

apologize and give a reason why. To put it another way, in self-imposed social

occupations the individual voluntarily gives up a portion of his available time to an

institution (philanthropic, political, trade-union body), and the management of that

time is transferred, to a certain extent, to that institution.

Finally, genuine free time can be further divided into three different kinds of

activities: nonautotelic voluntary occupations, sterile free time, and leisure in its

strictest sense. In a nonautotelic voluntary activity, the subject has absolute autonomy in deciding whether and how to carry out the activity, but the activity is not the

end in itself and performing the activity is not necessarily pleasant. An example

could be activities related to cultivating the body beyond that necessary to maintain

health. The difference between these and leisure activities is that the main motivation of the former is the achievement of something other than the gratification

offered by the activity itself. Those who devote a portion of their free time to lying

in a tanning machine do not always do so for the pleasure offered by this act but

rather to show off a tan.

Sterile free time is poorly lived free time, i.e., time that generates feelings of tedium

and frustration, a whiling away of time but with a bad conscience. It is called sterile

time not because it is not productive (because leisure is not productive either),

but because when a person does not produce anything, there is no satisfaction for

that person who has sterile time on his hands. Sterile time is time to which not even the

subject himself gives significance.

28.2.2 Three Basic Conditions of Leisure and Their Application to

Childhood

The concept of leisure refers to a type of activity rather than a type of time. Leisure

is closely related to free time, but the two should not be confused or considered to

be exactly the same. In this section, we first discuss one of the most classic and wellknown definitions of leisure, proposed some years ago by the French sociologist

J. Dumazedier; and second, we propose a more restrictive and coherent characterization of leisure in accordance with the preceding outline and considerations.

Based on a survey of individuals perception of leisure taken early in the second

half of the last century, Joffre Dumazedier (1915-2002) proposed the following

definition of leisure (Dumazedier 1960): Leisure consists of a number of

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

869

occupations in which the individual may indulge of his own free will either to rest,

to amuse himself, to add to his knowledge or improve his skills disinterestedly or to

increase his voluntary participation in the life of the community after discharging

his professional, family and social duties. After stating that leisure is a kind of

activity or occupation, Dumazedier proposes one of its most essential characteristics: its voluntary nature. To be considered a leisure activity, it must give the

individual the freedom to decide to do it or not. The definition goes on to give

the characteristic functions of leisure: rest, amusement, and development. Finally,

the definition establishes the conditions that make leisure possible. Leisure can take

place once the individual has freed a portion of his time from work, family, and

social obligations. Dumazediers definition thus offers a broader conceptualization

than that proposed by the previous outline since it coincides with what we call

available time. In this sense, a different way to characterize leisure is that it consists

of any activity in whose performance the following three conditions converge:

autonomy, autotelism, and pleasure/satisfaction.

28.2.2.1 Autonomy

We understand the first condition, which we call autonomy, but for which other

words such as freedom or voluntariness are also often used, in a twofold sense:

autonomy in the what and autonomy in the how. Autonomy in the what means

freedom to choose the activity. Thus, leisure presupposes the existence of free time.

He who has no free time according to the characterization of the concept we

propose above is unlikely to enjoy leisure. Autonomy in the how means that

during the activity the individual maintains control over its development and how it

unfolds. However, since these concepts (autonomy, freedom, and voluntariness) are

extremely complex and subjective, and to avoid falling into an idealistic or idyllic

view of leisure, we must add at least two additional clarifications. First, the

autonomy referred to is relative. It is obvious that as in any other aspect of life,

autonomy in leisure is never total. In relation to leisure activity, each individual

enjoys a defined level of autonomy that we call the freedom field, which is made

up of a variety of factors, discussed below.

Contextual factors. The context (family, social, cultural, geographic) gives the

subject a set of possibilities with which to fill his leisure with content. These

possibilities refer to the availability of spaces, resources, and products, as well as

to that of people with whom he can relate (peer groups, family, friends). Thus, the

freedom field of a specific individuals real free time depends upon the range,

diversity, and richness of the set of possibilities that his context offers. As a simple

example, if someone lives in a tropical country, the daily practice of Nordic skiing

is not part of his freedom field.

Socioeconomic factors. While important, contextual factors often do not act

alone in determining leisure activity. In fact, what really affects this is the place

the individual occupies in the context, e.g., his social role or economic status.

Accessibility to certain leisure possibilities offered by the context also depends

on the individuals ability to afford them economically.

870

J. Trilla et al.

Psychophysiological factors. Each persons freedom field is limited (or enabled)

by their psychophysiological and evolutionary status. Leisure options vary

depending on each individuals development, state of health, and so on.

Stereotypes and selective or discriminatory traditions. The leisure context also

includes a set of social codes, moral norms, customs, traditions, fashions, and

stereotypes that constrict real possibilities in the use of free time. Such codes

guide and sometimes impose (or deny) certain leisure pursuits according to variables such as gender and family role (e.g., girls have to play with dolls, and boys

with toy soldiers).

Educogenic factors. The personal and, in particular, educational background

(schools, family, and informal education) determine the leisure of each person.

Depending on this background, certain individuals will have the necessary aptitude,

abilities, skills, and disposition (or not) to make a leisure activity viable. There are

cultural and instrumental skills (languages, techniques, knowledge) and propensities that are necessary to be able to enjoy certain kinds of leisure. While a person

may be able to afford a certain activity, unless their previous education has instilled

in them a certain predisposition for that activity it is unlikely to form part of their

field of possible choices. A child choosing to read for leisure depends not only on

the availability of books or libraries but also on whether his or her education has

aroused a taste for reading.

Another point that needs to be made about autonomy as an essential condition

for leisure is that it must be understood as a subjective feeling of autonomy,

something akin to what Neulinger (2000) calls perceived freedom. Leisure can

be and indeed often is induced, manipulated, or alienated. Moreover, in this

sense and as is discussed later, leisure can be more subtly or subliminally induced

than other activities that are imposed in a direct or explicit way. However, to call

something leisure, the subject must at least have the subjective consciousness that

he is acting voluntarily, even when objectively and from the outside it may be

obvious that the individual is being heavily manipulated. At this point we are not

trying to define positive leisure, just leisure and nothing more. Consequently, while

the individual is aware, albeit incorrectly, that he or she has chosen leisure autonomously, even the most manipulated and unconsciously directed leisure is no less

leisure than leisure of the most personal, creative, and truly autonomous nature.

28.2.2.2 Autotelism

The second condition in defining leisure is autotelism, highlighted by Aristotle as

the most essential part of this concept. It means that the leisure activity has purpose

in and of itself (Cuenca 2004). Even when the activity can produce certain results or

material goods, and even when one of the individuals motivations is to obtain such

an outcome, the first justification of the activity must be the intrinsic satisfaction

that it is able to produce. A person who likes fishing, if successful, obtains

a material product from the activity a fish that he can eat or give to friends.

However, a pure leisure activity seeks no reward; it is partaken in because the

fisherman likes fishing and feels good when doing it. As is well known, many

fishing enthusiasts return their catch to the sea.

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

871

28.2.2.3 Pleasure and Satisfaction

This brings us to the third essential condition: leisure as a pleasant task, satisfactory

and fun. An unpleasant, boring, or tedious leisure activity is, if anything, simply

failed leisure; it is not really leisure at all but the sterile time discussed above. The

pleasure or satisfaction referred to here, however, should not be confused with the

most rudimentary or prosaic meaning of amusement. The leisure activity does not

necessarily mean laughter and revelry, it means being happy with what you are

doing. And leisure does not exclude effort. Those who devote leisure time to

solving intricate chess problems call upon a considerable amount of intellectual

effort, and the physical or psychological effort of those who climb mountains is no

less significant. However, both chess and mountain-climbing may well be considered leisure because despite being activities whose pursuit requires effort, they are

also enjoyable to those who participate in them.

To summarize, regardless of a particular activity, leisure consists of the use of

free time to engage in an autotelic occupation, autonomously chosen and

performed, whose practice is pleasant for the individual.

The concept of leisure must be applied to the different stages of life, taking into

consideration the specific parameters (especially social and psychophysiological)

that characterize each stage. Specifically, childrens leisure has two features that at

first glance appear contradictory: one that plays down autonomy and another that

would make childhood a privileged period for leisure.

If it is possible to establish comparisons between the different stages of life

based on the role played in each of them by the extremes of security-autonomy,

dependence-independence, or control-freedom, it is obvious that, in general terms,

during childhood the importance of or need for the first term in each pair is greater

than in subsequent stages. Psychogenic and physiological characteristics, socioeconomic conditions, and legal frameworks constrict the possible autonomy of a child

in favor of protection and custody. These questions, which naturally affect all

aspects of a childs life, are particularly relevant with regard to leisure. Physical

and mental immaturity, economic dependence, and laws that limit the legal responsibilities of children define the possibilities for childrens leisure that render them

qualitatively and quantitatively different from those of an adult. In terms of an

absolute and somewhat idealistic concept of freedom, this would mean that the

level of autonomy in childrens leisure is lower than in the following stages of life.

However, even if that were true, it would be nothing more than a trivial finding

unless it produced more operational consequences.

The greater need for custody in childhood can be understood either as a restriction on a childs autonomy of leisure or, more positively, as a requirement for

a more appropriate form of protection and oversight of the childs possible autonomy. Since this autonomy is more fragile, more easily manipulated, and more open

to arbitrariness exercised by persons and institutions that have control over childhood, appropriate mechanisms must be established to protect child leisure. Some of

these mechanisms already exist but are not always adequate. They are often ladened

with adult projections, double standards, and an excessively protectionist spirit.

Rather than actually protecting childrens leisure, these mechanisms limit and

872

J. Trilla et al.

reduce childrens leisure even more than may be justified or reasonable. Of course,

it is not easy to find the right balance between security-autonomy, dependenceindependence, and control-freedom, but if in all aspects of childhood the search for

such balance is necessary, in that of leisure it appears as one of the principal

educational challenges.

While it is true that childrens leisure is more constrained than that of adults,

paradoxically there exists a diffuse ideology that considers childhood a privileged

period for leisure and play. Indeed, a good deal of what constitutes the cultural

concept of childhood which, according to the well-known thesis of Arie`s (1996),

has been forged in the modern age is made up of elements that are related to

leisure. Todays concept of childhood is being shaped by progressive schooling, the

consequent distancing of the world of work, formation of the bourgeois nuclear

family, and other elements often closely related to leisure, e.g., specific clothes for

children, differentiation between child and adult games, the emergence of childspecific literature, and so on.

This modern concept of childhood is basically represented through three additional images that place the child respectively in the school, the family, and at play.

Literature and iconography illustrate these three images corresponding to the three

fundamental roles in modern childhood: the schoolchild, the child as son/

daughter, and the playing child. Thus, the world of play becomes one of the

three fundamental contexts of childhood. And no sooner do we consider it a world

typical of that period, the social construct excludes all other periods of life from the

recreational world: adult play, for example, is thought of as childish, a residue of

childhood, or at best something accepted as a way of keeping physically and

mentally fit for work and thus subordinate to it. In this construct, it is most

appropriate for a child to learn and play and for an adult to work. Thus, according

to this modern view of the roles of each stage of life, the world of play and by

extension, leisure corresponds, in a privileged fashion, to childhood.

28.3

Leisure and Education

28.3.1 Justification of Educational Intervention: Values and

Countervalues in the Context of Free Time and Leisure

Social representations of free time and leisure have differed throughout history.

Both positive and negative images of leisure have been created. Leisure as something positive and desirable is how it was portrayed in classic Greece and Rome,

with different contents in each case. The ancient Greeks and Romans understood

leisure as a value, even as something dignified that could make life virtuous and

happy. Conversely, leisure has at various times been represented as just the

opposite, a countervalue, a vice, or the source of all evil. This is the Puritan concept

of leisure that dominated certain attitudes from the seventeenth century and is still

present today, though perhaps only residually.

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

873

In this sense it is interesting to note how certain reflections that tried to propose

a positive social image of leisure provocatively used the negative connotations

imposed by bourgeois Puritanism on such terms as laziness or idleness. In The Right

to Be Lazy (1880), Marxs son-in-law Paul Lafargue argues that we should aspire

not to the right to work, but to the right to welfare. He began the first chapter of his

work with the following quote from Lessing: Let us be lazy in everything, except

in loving and drinking, except in being lazy (Lafargue 2002). In a 1932 essay

suggestively entitled In Praise of Idleness, Bertrand Russell wrote:

Like most of my generation, I was brought up on the saying: Satan finds some mischief

for idle hands to do. Being a highly virtuous child, I believed all that I was told,

and acquired a conscience which has kept me working hard down to the present moment.

But although my conscience has controlled my actions, my opinions have undergone

a revolution. I think that there is far too much work done in the world, that immense

harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous, and that what needs to be preached in

modern industrial countries is quite different from what always has been preached.

Everyone knows the story of the traveler in Naples who saw twelve beggars lying in the

sun (it was before the days of Mussolini), and offered a lira to the laziest of them. Eleven

of them jumped up to claim it, so he gave it to the twelfth. This traveler was on the

right lines. . . . The wise use of leisure, it must be conceded, is a product of civilization

and education. A man who has worked long hours all his life will become bored if he

becomes suddenly idle. But without a considerable amount of leisure a man is cut off from

many of the best things. There is no longer any reason why the bulk of the population

should suffer this deprivation; only a foolish asceticism, usually vicarious, makes us

continue to insist on work in excessive quantities now that the need no longer exists

(Russell 1960).

As we mentioned before, free time is basically like a container. It can host

values and countervalues, positive social functions, and other more dubious

contents, positive leisure and negative leisure all at the same time. Thus, it

would be realistic and reasonable to see that just as any other social reality in

a world of contradictions, free time and leisure are ambivalent and contradictory

realities.

Figure 28.3 summarizes some of the values ascribed to leisure and their

corresponding countervalues, which are discussed in the following sections.

28.3.1.1 Freedom, Autonomy, Independence versus Alienation,

Manipulation, Dependence, and Control

Free time is, as the name suggests, an area of freedom, a time when personal

autonomy should dominate when choosing an activity and how to do it. It is the

freedom in the what and the how mentioned above. However, it is also a time

for alienation and manipulation: alienation made more dangerous because we are

not generally aware of it. We all know only too well that work is usually subject to

someone elses decisions or processes that we cannot personally control; yet at the

same time we may be under the impression that we do what we want in our free

time, when in reality it is a time often subject to hidden pressures, stereotypes,

fashions, and control.

874

J. Trilla et al.

VALUES

freedom, autonomy

COUNTER - VALUES

alienation, uniformity, manipulation

happiness, pleasure, amusement

frustration, boredom, tedium

autotelism, disinterested knowledge

ostentation, leisure merchandise

creativity, personalisation

consumerism, mass production

sociability, communication

isolation, lack of communication,

negative solitude

activity, self-motivated effort

passivity, indolence

culture

cultural trivialisation

everyday values

monotony, inertia

extraordinary values

extravagance, the bizarre

solidarity, social participation

lack of solidarity, indifference

Fig. 28.3 Values and countervalues of leisure and free time

28.3.1.2 Happiness, Pleasure, Amusement versus Frustration,

Boredom, Tedium

The other essential feature of a leisure activity is the satisfaction or pleasure

produced by its realization. However, free time is also a producer of dissatisfaction,

frustration, unhappiness, boredom, and tedium. Leisure activity can produce

dissatisfaction when we do not have access to certain products because the leisure

activity is something that creates want and at the same time is extraordinarily

selective and discriminatory. Frustration can arise from having high expectations

(e.g., about a holiday) that will never be achieved. Free time can also produce

unhappiness in the form of a guilty conscience generated by the still-present Puritan

work ethic because we are not doing something apparently useful or profitable.

Finally, free time (supposedly the quintessential time for pleasure) is occasionally

a time of boredom and tedium, sometimes because it is not easy to ascribe any sense

to such time since it is yet to be fairly valued by society, and sometimes because we

have not had the opportunity to learn how to use it satisfactorily.

28.3.1.3 Autotelism, Disinterested Knowledge (Value of Use) Versus

Utilitarianism, Ostentation, Leisure Merchandise (Value of

Exchange)

We have already seen that according to the Aristotelian concept, leisure is an activity

that has an end in itself. However, in contrast to this autotelic leisure value, there is

the countervalue of leisure as a form of ostentation, as shown by Thorsten Veblen in

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

875

his now classic work from 1899, The Theory of the Leisure Class: leisure as

a symbol of status, wealth, and power (Veblen 2004). An example would be one

who travels not for the pleasure of travelling in itself, but to show off that he can

afford to go to fashionable destinations. This leisure merchandise includes the free

time of those who use tanning machines or work out in the gym, not for health or

wellness but to show off their fantastically beautiful body. Countervalue also

includes the value of free time employed in activities and relationships by

those whose aim is to climb the social ladder. Leisure is thus perverted when its

ostentatious function predominates over its value of use and the very sense of the

activity itself.

28.3.1.4 Creativity, Personalization, Difference versus Consumerism,

Mass Production

It is said that leisure is also the most suitable time for exercising creativity, for an

occupation dominated by the highly personal nuance that each individual can give

it, a time for personalization, originality, creativity, and authenticity. However, the

opposite often occurs: leisure pursuits can be the most mass-produced, vulgar,

uniform, and mediocre of all human activities. It is not difficult to perceive the

real contradiction that leisure (the abstract kingdom of personalization) is something even more impersonal than work itself. It would be hard to find 100,000

individuals doing exactly the same thing at exactly the same moment at work, yet

this occurs regularly at a football stadium or when thousands are on the road

returning from a leisurely weekend, or millions of people are watching the same

TV show at the same time.

In regard to consumerism, we can see that not only has the consumption of

products and services and the use of institutions and professionals become essential

for leisure, consumption itself has become a leisure activity. Going shopping (or

window-shopping) and walking around the mall are considered leisure activities as

much as going for a walk, to the cinema, or to the theatre.

28.3.1.5 Sociability, Communication Versus Isolation, Lack of

Communication, Negative Solitude

Free time is a special time for social relationships and communication but it is also

a time when solitude (of the negative or unwanted variety) is even more obvious

and pathetic than in any other moment in life (Kelly 1983). The loneliest solitude is

what we feel when alone at a party, when we have no one to go out with on

a Saturday evening or to go on holiday with.

Likewise, there are other pairs of values and countervalues that fall into free

time: time for activity, self-motivated effort, indolence, and passivity, or, in contrast, time for frenetic, blind activism, culture, banality, and cultural frivolity; space

where the best of the everyday can be realized (relaxed relationships with others,

gathering for coffee, and the small, enriching hobbies we all have), as can the worst

of monotony, inertia, and routine; time too for the extraordinary, adventure, but also

fertile ground for simple extravagance; and finally, time for solidarity and social

participation as well as for indifference and not caring.

876

J. Trilla et al.

Free time is, therefore, an ambivalent and contradictory reality: a container filled

with the best and the worst contents, the best and the worst possibilities. Pedagogy

must begin to recognize it as such because it is precisely this ambivalence that

justifies educational intervention in leisure. If free time were an idyllic reality,

a world in which freedom, creativity, sociability, and solidarity truly predominate,

pedagogical action would be unnecessary if not hazardous: If it aint broke, dont

fix it. If free time were the best of all worlds, there would be no reason to improve

it with education. The fact that free time leaves much to be desired is precisely the

reason that educational action is needed.

On the other hand, if free time failed to offer real expectations of social and

human development, pedagogy should not intervene either, and it would be better to

find a more suitable area for intervention (Kleiber 1999, 2001). The pedagogy of

leisure makes sense precisely because of the ambivalent reality of free time;

because leisure time is abounding in values and countervalues, in positive and

negative possibilities, in noble and harmful contents, and in which educational

action can help optimize. To achieve this, however, the educational intervention

would have no alternative than to make value choices, options that will promote

certain forms of leisure and reject others. That is perhaps why after highlighting its

virtues in general, so many experts who have studied the educational issues relating

to leisure end up qualifying it with adjectives: creative leisure (Csikszentmihalyi

2002), serious leisure (Stebbins 1992, 2007), humanist leisure (Cuenca 2000).

Without these or other positive adjectives, educational intervention in leisure

would be confused and aimless.

28.3.2 Purpose of the Pedagogy of Leisure

The relationship between education and free time/leisure is often approached on the

basis of the two concepts respectively referred to as education in free time and

education for free time. In the former, free time would simply be a space

that could be used to host some type of educational activity. In the latter, free

time becomes the educational objective. Both approaches are logically distinct

but not necessarily conflicting or contradictory. In analyzing them a possible area

of convergence can be seen (Fig. 28.4). When free time is taken as a space for

some educational process (education in free time), there are two possibilities: One

is that the process is oriented toward purposes that have nothing directly to do with

leisure, e.g., the child who has to devote some part of his non-school time to

receiving private classes. The other possibility is that the educational process that

takes place in free time is directed at developing some kind of knowledge, skill, or

attitude that allows the individual to use his leisure in a richer, more positive, and

pleasant way.

Something similar occurs when free time is understood as an objective (education

for free time). Two alternatives may also be considered in this case: that education for

free time can be achieved in typically leisure situations or in contexts outside that of

leisure, such as the school (Ruskin and Sivan 2002; Sivan 2008). It is conceivable that

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

877

Aimed at nonleisure purposes

Education IN

free time

Aimed at leisure

purposes

Education

THROUGH

leisure

In leisure situations.

Education FOR

free time

In non-leisure

situations

Fig. 28.4 Relationship between education and free time. The purpose of the pedagogy of leisure

even in its curricular activity, the institution of school could include among its goals the

provision of cultural resources that enable richer leisure possibilities. For example,

the subjects of language and literature could be useful not only for learning spelling

or the history of literature, but also for developing the capability and sensibility to

enjoy reading.

Doubtless the core of the outline described above would constitute a more

specific justification of the pedagogy of leisure. That is to say, the most suitable

purpose of such pedagogy would be to educate simultaneously in and for leisure.

In fact, the combination of both approaches reinforces each individually. To use

free time for purposes contradictory to it, though perfectly legitimate, means

converting that time into something else; this free time evidently ceases to be

experienced as such. On the other hand, it seems that the best way to educate for

leisure is to do so in free time, in other words, through leisure. It would not

be necessary to insist on this if we were not so accustomed to forgetting the simple

core statement of active pedagogy: What we learn is what we do. The best way to

learn how to use free time in a very autonomous, pleasant, and creative way is

naturally through situations and activities that effectively make such conditions

a reality.

Thus, in a limited sense the pedagogy of leisure would be education through

leisure (that is, simultaneously in and for free time). In a broader sense, however, it

may also include the other possibilities mentioned in the full outline.

878

J. Trilla et al.

28.3.3 Factors in the Development of the Pedagogy of Leisure

Having described the general justification for educational intervention in leisure,

we now examine a number of factors that have motivated the emergence and

development of a diverse but quantitatively significant set of institutions, programs,

resources, facilities, and educational activities related to childrens free time. We

consider the reasons for the proliferation of free-time educational centers, toy

libraries, extracurricular activities, summer camps, scouts and guides, and a long

and varied list of other organized educational provisions in our society.

There are two reasons for the appearance and development of new educational

institutions or interventions. The first stems, in principle, from outside education

itself and consists of social, economic, demographic, and political factors. There are

educational needs that arise as a consequence of phenomena that initially have little

to do directly with education. A clear example is nursery schools. Centers for

early-childhood education were first created not so much for educational needs

but rather for custody. It was the incorporation of women into the work world

outside the home that caused the need for such schools. It is from there that

the pedagogical discourses began to emerge to legitimate on the one hand and

implement on the other this form of infant education. Applying this idea to the other

end of life, the same could be said of the increasingly cited and demanded

pedagogy for the elderly. Interventions and programs with educational content

addressed to senior citizens have not appeared because only now have we discovered that the elderly can continue learning (this has always been known), but

rather because of factors as far from pedagogy as the increase of life expectancy

or the advancement of the retirement age. In short, pedagogical actions are often

responses to situations produced by factors that are not initially directly related to

education.

It is also true that this kind of sociologistic explanation for educational intervention does not entirely address its raison detre. Social factors explain the

emergence of the need for and characteristics of a certain area of action, but they

cannot account for the peculiarity of the educational response that such need

receives. In order to prepare a response, pedagogy has to be theoretically and

technically prepared. It is for this reason that clarification of the genesis of new

educational interventions also demands recourse to the internal pedagogical discourse, to its conceptual and theoretical basis, to the technical background it has

accumulated, and to possible antecedents that prepare and facilitate new educational actions.

28.3.3.1 Social Factors

Among other possible factors outside the field of educational science that have

converged to create the need for educational institutions addressing childrens free

time, there are two that are particularly relevant and paradigmatic. One is the

gradual disappearance of traditional spaces for spontaneous play and the informal

horizontal socialization of children, and the other is the partial loss of the familys

role in safeguarding and giving content to their childrens leisure.

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

879

It is hardly surprising that the pedagogy of leisure was originally

a fundamentally but not exclusively urban reality. It was in cities where the need

for playgrounds, toy libraries, and organized summer activities urgently arose. This

was primarily due to the very young being increasingly deprived of their traditional

spaces for play and peer relationships. Traffic and safety issues expropriated the

street from children, and land speculation and excessive construction did the same

with other natural spontaneous play spaces (vacant plots of land, nonurbanized

areas). It is true, however, that play can be adapted to environmental conditions.

Moreover, the conditions themselves often become the reason for or means of the

recreational activity. The city, as Jane Jacobs (1961) brilliantly described in The

Death and Life of Great American Cities, with its streets and squares, markets and

shops, neighbors and passers-by, trees and pavement, has served as a stimulus,

argument, playing field, hideout, and place for adventure for childrens spontaneous

amusement. However, despite this huge capacity for play to adapt, which materially

and symbolically transforms any environment into a space and object for play, there

is a point where conditions become so adverse that this proves impossible. The city

then becomes a dangerous and hostile place for the child (Tonucci 1997). It is true

that the sight of children playing in the street is disappearing from the urban

landscape, thus creating the need for alternative scenarios: toy libraries, enclosed

and expressly designed playgrounds, or commercial recreational spaces.

Another major social factor that has created the need for childrens free-time

educational institutions is the family. Certain transformations in family life have

resulted in the reduction or loss of some of the familys traditional functions in

relation to childrens leisure. In addition to being an economic unit and the heart of

affective relationships, the traditional nuclear family was a leisure community, i.e.,

the framework in which a good deal of its members took part in free-time activities

together. School and the nuclear family became established as the two main

institutions for childrens custody and education. But while the school played

a minor role in the direct provision of child leisure activities, the same could not

be said of the family. For the very young and to a lesser extent the slightly older

child the most significant natural setting for their leisure was in the family

environment. Directly or indirectly, and for better or worse depending on the

case, the family was the most relevant authority to guide, enable, and give content

to childrens free time. Control over and responsibility for childrens leisure rested

traditionally within the family institution, which shaped both everyday leisure

activities and those weekly or annual routines (weekends and holidays).

This picture of family leisure has been changing in parallel with other alterations

taking place in that institution. Womens work outside the home, a significant

relaxation of relationships within the family, progressive disengagement of the

conjugal family (parents and children) in relation to other family members (grandparents, uncles, aunts), the quest for higher levels of personal autonomy for each

group member, or the diversity of todays family models (reconstructed families,

single-parent families) are factors that have blurred the image of the family as

a leisure community. It is true that the family is still important in this task, but

a series of educational institutions has appeared to take over the familys role.

880

J. Trilla et al.

Summer camps, childrens clubs, extracurricular activities, and the like now

assume the functions related to childrens free time that were previously carried

out within the family structure.

28.3.3.2 Pedagogical Factors

The previous section offers examples of social factors at the root of the need for

free-time educational institutions, but to enable them to be developed and extended

there must also be a relevant pedagogical discourse that legitimizes and justifies

them. This is examined in the following section.

Broadening the Concept of Education

One of the most significant theoretical evolutions to have taken place in pedagogy,

especially since the second half of the twentieth century, was the broadening of the

concept of education and, consequently, extending the possible range of intentional

educational interventions. On the one hand, there has been a vertical extension:

From considering childhood and youth as almost the only stages at which we are

susceptible to education, we have moved to accepting, without reservation, that we

are receptive to teaching throughout our entire life. The concepts of lifelong

learning and continuing or recurrent education for adults, and even the elderly,

are now commonly accepted in the education sciences. Another expansion has been

horizontal. The concepts of nonformal and informal education (and others that are

parallel or similar such as open learning and extracurricular education) demonstrate

the idea that education extends far beyond the strict confines of the school (Trilla

1993b). If we accept these concepts, we cannot ignore the educational scope of the

design of play spaces and materials, free-time educational centers, and, in general,

the wide range of institutions and resources that will shape an entire field of leisure

education.

Recognition of the Role of Play in Development

Recognition that play is an essential activity for childhood development is another

factor that legitimizes the pedagogy of leisure. This is not the place to review the

many explanatory theories used to justify the pedagogy of leisure, but it is necessary

to highlight the fact that almost all psychological theories about childrens play

stress the importance it has in child development. Since the theory of K. Groos, who

explained that play is a preparatory exercise for adulthood and which he considered

a spontaneous mode of self-education, all subsequent authors on the subject

(W. Stern, S. Hall, E. Claparede, F. Buytendijk, K. Buhler, J. Piaget, and the

psychoanalytic theorists) have emphasized one aspect or another but they accept

the role of play in development (Elkonin 2010). Some, like Vygotsky, go even

further by considering play a basic factor of development and a conducting

activity that determines the childs development (Vygotski 2001, pp. 154-155).

Play is not the only free-time activity, but it is one of the most paradigmatic,

above all in early childhood. Thus, recognition of recreational activity as a factor in

childhood development necessarily had to strengthen the refinement of pedagogical

reflection on free time.

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

881

Growing Appreciation of the Values Traditionally Marginalized by School

The school as an institution traditionally has favored the intellectual over other

learning dimensions of the individual. However, the pedagogical requirement of

a comprehensive education that omits none of the facets of the human being and

harmoniously strengthens each of them is now dated. The idea of integral education

is a long-standing pedagogical aspiration that school has rarely satisfied in practice.

This institution has focused on cognitive aspects, while in the curricula and practice

in general the presence of emotions, sociability, artistic expression, or even physical

education (other than the few exceptions that simply prove the rule) have traditionally occupied a secondary and subordinate role.

If the integral education discourse served to reassess a series of personality

aspects such as those mentioned above and the educational institution par excellence, i.e., the school, failed to assume them to a satisfactory extent, other areas or

educational institutions should have assumed them on a supplementary basis.

However, the school, or at least the traditional school, was reluctant to accept

a set of values that were being updated ideologically, such as spontaneity, autonomy, creativity, relationship with the environment, and so on. The organizational

models of the traditional school (rigid, fossilized, bureaucratic, and hierarchical)

and their methodologies (rote learning, passive, decontextualized) were, in fact, the

antitheses of the values that the most advanced pedagogy was demanding.

In short, the theoretical overview of pedagogy was growing with a set of new or

recovered goals and values that conventional educational institutions failed to

properly address. What was being asserted was that the cultivation of creativity,

sociability, self-expression, and autonomy would perhaps be more in keeping with

a kind of educational institution or medium that had free time as a sphere of action.

Thus, it is a fact that leisure educational institutions have championed the values

mentioned above. On occasion they have assumed them in the belief that they

should do so as a necessary complement (or supplement) to the school.

Formulation of the right to education in free time

Article 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United

Nations in 1948, already established the right to the leisure: Everyone has the right

to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic

holidays with pay. The definition of this right in the case of children, as established

in 1959 by the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child, explicitly linked it

to education. Principle 7 of the Declaration, devoted specifically to education, states the

following: The child shall have full opportunity for play and recreation, which should

be directed to the same purposes as education; society and the public authorities shall

endeavour to promote the enjoyment of this right. In the update of the document which

led to the Convention on the Rights of the Child adopted in 1989, also by the United

Nations, an entire article is dedicated to childrens leisure. Article 31 states that

(1) States Parties recognise the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in

play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate

freely in cultural life and the arts. (2) States Parties shall respect and promote the right

of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall encourage the

882

J. Trilla et al.

provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and

leisure activity. Furthermore, many nations have incorporated explicit references to

the childrens right to leisure and education in their free time into their own legislation

(constitutions, and educational, social, and cultural laws) (Lazaro 2006).

Obviously, the legal recognition of a right does not mean that in reality the

necessary conditions exist for everyone to exercise it, let alone have equal opportunities to do so. Social and economic inequalities in the formal educational system

are certainly the same or probably even more so for free-time education. Nonetheless, it remains true that these legal formulations regarding education in free time

have contributed to the social endorsement of this educational area and to the public

bodies that are gradually assuming their responsibility in relation to it.

28.4

Specific Areas of the Pedagogy of Leisure

28.4.1 Institutions, Programs, Activities, and Resources

As we have seen, educational activities related to free time can take place in a very

wide range of institutions, programs, facilities, activities, and resources. In fact, all

the educational contexts and mediums that have a bearing on the use that individuals make of their free time should be considered areas of the pedagogy of leisure.

The simplest way to organize the existing diversity of these areas is to divide them

into two groups: specific and nonspecific.

Specific areas of the pedagogy of leisure would be all those institutions and

activities that are simultaneously specifically educational and specifically linked to

free time, i.e., institutions expressly created for the purpose of educating through

pursuits that are characteristic of leisure. This group includes toy libraries, educational activities for holidays, childrens free-time clubs, and certain extracurricular

activities. Nonspecific areas would be those that are not specifically educational and

are not specifically linked to free time, i.e., school, family, and leisure industries.

The school is a specifically educational institution but, except at specific times, does

not act through free-time activities; leisure industries obviously address free time but

are more accurately characterized by their economic and commercial components

than by the components potentially connected with education. As nonspecific

mediums have already been widely and expressly discussed in other chapters of

this book, we present the most significant specific institutions, activities, and

resources in the following sections (Calvo 1997; Puig and Trilla 1996; Trilla and

Garca 2002).

28.4.1.1 Children Clubs and Centers for Free-time Education

Children clubs and centers for free-time education refer to a wide range of institutions that have different names according to the traditions of each country but they

explicitly approach free time as an area for educational intervention and assume it

in an overall fashion. They do not specialize in just one kind of leisure activity such

as toy libraries or other institutions which we discuss below. Children centers are

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

883

constituted as spaces for meeting and a range of activities, with the presence of

facilitators (professionals or volunteers) and where the users are usually children

from the same community. There are basically three types of children centers:

(1) those that operate on a weekly basis, (2) those that operate on a daily basis, and

(3) those that operate only at specific times of the year (mainly during school

holidays).

Despite the organizational and institutional diversity and the variety of pedagogical methodologies they may adopt, perhaps that which best characterizes this

type of educational institution is the collective leisure dimension that they facilitate

and encourage. Without eliminating the possibility that a child may choose some

individual leisure activity while at the club (reading or playing alone, for example),

the purpose of this institution is to be a place of encounters. If these childrens clubs

have any justification it is to provide the option of collective play, activities that

require company and reciprocity, cooperative leisure, building peer relationships,

and shared projects.

28.4.1.2 Holiday Educational Activities Performed Outside the Childs

Place of Residence: Summer and Overnight Camps,

Excursions, Volunteer Camps

As reflected in the section heading, in this section we bring together a variety of

childrens free-time educational activities that share the characteristic of taking

place outside their usual place of residence. Despite their limited duration (generally 10-15 days), they have relevant educational potential that can be summarized

by the following characteristics:

1. Intensity of the experience. These are short but remarkably intense experiences

as they encompass the totality of the childs life, 24 h a day. In terms of time,

they represent a total educational situation. This requires a more comprehensive

pedagogical approach than other, part-time leisure educational institutions.

2. Opportunity of educationally addressing the everyday. From that described

above, these activities include a variety of everyday life situations (meals,

sleeping, down time) which are omitted from possible pedagogical interventions

in other educational institutions except in the family or at boarding school. The

treatment of everyday events as an area of meeting primary needs is one of their

most important educational dimensions.

3. Temporary separation from the family environment. For the child, these activities mean experiencing temporary separation from the physical, emotional,

relational, and regulatory bastion of the family environment. For younger children, this may be an important moment in the necessary and progressive process

of reducing family dependency. The subject experiences a different model of

time management, relationships, and so on that provides a more objective

perspective of their own customary family model.

4. Contact with a different environment. For the city child, a stay at a summer camp

offers the possibility to know the rural world first hand and to have direct contact

with nature. Since these activities are not limited to city children, they always

represent a change from the childs own environment, with a broadening of his

884

J. Trilla et al.

or her horizons, with all that it may mean (e.g., ways of life, customs,

landscapes).

Other formats also exist in this group of educational activities, e.g., thematic

summer camps where all the activities revolve around a certain area of interest (e.g.,

sport, music, ecology); volunteer camps where the holiday dimension makes

room for carrying out some form of service, whether social, agricultural, or

archaeological in nature; or treks (walking, cycling), which would be something

akin to travelling camps.

28.4.1.3 Playgrounds and Recreational Open Spaces

Though we must continue to insist that urban policies, where possible, adopt as one

of their objectives the recovery of streets and public squares as favorable places for

spontaneous play, this does not deny the fact that it may often be necessary to adapt

open spaces to ensure that children have the opportunity to play outdoors. From

a pedagogical perspective there are two fundamental criteria to consider when

designing play spaces: they must be based on the real requirements of spontaneous

play and they must stimulate and enrich such recreation.

In regard to the first criterion, it must be said that any intervention to set up play

spaces and their equipment should be based on knowledge of the reality of

childrens play. Direct observation of spontaneous games is a necessary source of

information in designing a truly functional park. The needs of different age groups

must be taken into account when determining the size of the space and its elements.

Younger children must be able to play with earth, sand, and water, and depending

on the location of the park, they should do so in a more or less protected space. It

would be appropriate to have conventional play elements at their disposal (e.g.,

slides and swings) as well as multipurpose structures that can be turned into a house,

hideout, or shop counter. Older children will require more open spaces where team

sports can be played, an element that entails a certain amount of controlled risk.

Nonetheless, just as we mentioned above that it would not be appropriate to isolate

leisure spaces too much, it would also be unadvisable to separate play areas

according to different age groups. Interactions between children of different ages

are always enriching. Younger children try to imitate and emulate older childrens

play through observation; older children learn to respect the play of the young.

The design of the park must awaken new and richer play possibilities. This can

be achieved by shaping the land (e.g., level changes, slopes, vegetation, hideouts,

ponds, water channels, places for skating and biking, roundabouts and porches) and

the incorporation of certain elements such as structures, trampolines, tunnels, walls,

and painted signs on the floor. In general, spaces and components that allow for

multiple uses are preferable to those that are for special use. One of the virtues of

spontaneous play is the adaptation and symbolic and/or physical re-creation that the

child does with places and materials.

Parks or adventure playgrounds also deserve special mention. These are spaces

whose main characteristic is their intentional lack of specific order or explicit

structures. They are expressly designed desert islands in an urban environment. In

this kind of park, children enjoy absolute freedom in their use of the space and

28

After-School Activities and Leisure Education

885

usually have rudimentary materials at their disposal with which to build cabins,

hiding places, and so on. They are a way of facilitating the components of

experiment, adventure, secret, and apparent disorder that the group games which

children play often possess.

28.4.1.4 Play Centers and Toy Libraries

The playgrounds we have just discussed satisfy a part of the childs need to

enjoy adequate spaces for recreational activity. However, there are games

that require another type of equipment and special facilitators such as toys. Play

centers were created to provide this space and to expand the usability of these

facilitators.

The first toy library seems to have been opened in Los Angeles in 1934. In 1960,

UNESCO popularized the idea and since then they have spread worldwide.

In addition to their primary function (i.e., to provide an adequate public space

with good toys for childrens recreational activity), toy libraries usually serve other

purposes related to play and education: guiding parents on the purchase and use of

toys, the creation of new play materials, encouragement of activities and collaboration with other neighborhood institutions, and testing and assessing industrial

toys. Of course, toy libraries also address the tasks directly derived from their

primary functions, such as the selection of toys based on quality, hygiene, and

educational criteria; the cataloguing, repair, and maintenance of toys; and guidance

and help provided by facilitators in the use of toys.

As with outdoor playgrounds, an important aspect of toy libraries in relation to

their function as a social service is their location. The characteristics inherent in

their use make them a type of facility that must be easily and readily accessible,

which means their distribution should be decentralized. Rather than a few

macrocenters that entail a long journey to get there, it would be more beneficial

to establish a good network of small and medium-sized toy libraries that reaches

numerous neighborhoods and villages.

28.4.1.5 The Scout Movement

Founded in 1907 by the British military officer R. Baden Powell, scouting has been

one of the most popular child and youth movements in the world. Originally it

accepted only teenagers, but in 1914 admission was extended to include younger

children, and girls had their own scouting group in 1912. Leaving aside the (in

some cases) significant ideological and religious differences and nuances

that numerous national and international scouting associations have incorporated

into the movement, there is remarkable unity in the underlying principles and basic

methodologies of the scouting associations. In fact, scouting constitutes a complete

civic education program that has been enjoyed by thousands of young

people over generations. Though scouting is still a significantly active movement,

crises have been arising for some time over some of its more formal aspects such as

uniforms and rituals. On a deeper level, issues have also arisen because of certain

resistance to the much-needed methodological renewal that the movements

material and ideological transformation requires. Despite this, as far as our

886

J. Trilla et al.

subject is concerned, it must be said that the emergence and development of

many other free-time educational initiatives has been used the techniques, experiences, and people from scouting. Scout movements have covered and still cover an

important space in the framework of free-time educational interventions.

Some of the traits that mark other areas of the pedagogy of leisure (e.g., summer

camps, free-time clubs) are perfectly applicable to scouting. There is, however, one

fundamental difference: diverse methodologies, doctrines, and pedagogical

models usually emerge in other expressions of the pedagogy of leisure; in contrast,

scouting is in itself an entire educational methodology. Moreover, it is

a methodology based on and fueled by an explicit and well-defined philosophy

of life and education.

28.4.1.6 Monothematic Activities, Facilities, and Leisure Resources

Grouped under this heading are all the associative entities created to encourage,

usually altruistically, some particular artistic, cultural, or sports specialty during

free time. Members or practitioners of these kinds of activities partake of them

more for their content than for some utilitarian purpose. This does not prevent high

standards and demands being achieved on many occasions. In any case, the

enjoyment and satisfaction, which are the essence of any leisure activity, are

never lost. Examples are childrens choirs, folk groups, theatre groups, amateur

sports teams, and excursion groups. This category also encompasses a realm of

extracurricular activities that take the form of courses or workshops on a wide range

of subjects, including visual arts, dance, music, new technologies, yoga, and

languages. We should also include such institutions and facilities as libraries,

museums, zoos, and other cultural installations that usually offer specific programs

aimed at filling childrens free time through their educational sections or

departments.

28.4.2 Shared Structural and Functional Characteristics