Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Enhancing tribal self-governance

Transféré par

lexsaugustTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Enhancing tribal self-governance

Transféré par

lexsaugustDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

COMMENTARY

Enhancing PESA

The Unfinished Agenda

Kamal Nayan Choubey

Amendments proposed by the

previous Congress-led union

government to the Panchayat

(Extension to Scheduled Areas)

Act 1996 had the potential of

improving upon this progressive

legislation. Unfortunately, with its

successor pursuing different

priorities, the possibility of the

amendments being passed

remains rather low.

Kamal Nayan Choubey (kamalnayanchoubey@

gmail.com) is with the Nehru Memorial

Museum and Library, New Delhi.

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

febrUARY 21, 2015

bill for an amendment to the Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled

Areas) Act (PESA) 1996 was

released for public discussion by the

Ministry of Panchayati Raj (MoPR) on

2 December 2013. This bill, titled the

Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled

Areas) Bill, 2013, was formulated on the

basis of exhaustive recommendations by

the Sonia Gandhi-led National Advisory

Council (NAC) in December 2012. However, for many months, the government

did not initiate any concrete measure to

implement these recommendations and

only six months before elections the

MoPR released the bill for public discussion. The crucial point is that after the

formation of the Narendra Modi-led

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government at the centre, the bill is still available on the MoPR website seeking public

comments and opinion. It is pertinent to

ask that whether the provisions of the

new bill would be able to rectify the

vol l no 8

shortcomings of the PESA? What might

be the future of the bill during the term

of the BJP government?

The PESA has been recognised by many

activists and scholars as a progressive

law, because it gives some crucial rights to

village-level communities to manage their

lives and resources. The PESA, enacted

by Parliament in 1996, extends Panchayat Raj institutions to Schedule V (of the

Constitution) areas. In many parts of

Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand and Maharashtra, the Bharat Jan Andolan and

some other organisations mobilised people and created public pressure for the

enactment of the PESA. It is crucial to

note that the Dileep Singh Bhuria Committee, constituted in 1995 to prepare

reports for the extension of panchayati

raj in Schedule V areas, presented two

reports. One was for rural areas and the

other one was related to urban areas.

However, only recommendations related

to rural areas were accepted and the

PESA was passed by Parliament. There is

still no separate law for the urban areas

corresponding to Schedule V.

The PESA defines the gram sabha as an

organic self-governing community rather

than just a basic administrative unit of

self-governance. The member of a habitation is the natural unit of the community,

21

COMMENTARY

whose adult member constitutes the gram

sabha. The PESA has created a framework for autonomous and empowered

gram sabha in the Schedule V areas.

Communities are declared competent to

safeguard and preserve their culture

and tradition, exercise command over

natural resources, enjoy ownership of

minor forest produce and adjudicate their

disputes (Section 4(d), and 4(m)(ii)). It

empowers the village assembly to monitor

all state institutions, within its jurisdiction, such as schools and health centres,

with functionaries placed under its

control (Section 4(i), (j), (k) and (l)).

The PESA, however, has not been implemented in its true spirit and it has

been violated at many levels. First, since

the panchayat is a subject in the state list,

all states with Schedule V areas had to

change their panchayat acts in accordance

with the central act of PESA passed by

Parliament. In many states, this was only

partially implemented and some states

took many years to make rules for

Schedule V areas. Rajasthan is a prominent example of this case, where a state

act, based on the central PESA was

passed in 1999, but rules were not formulated until 2011. Since there were

many limitations in these rules, tribal

activists challenged it in the high court

and the issue is still unresolved.

Second many states formulated rules

according to PESA provisions and created a framework for the panchayat system in Schedule V areas, but some major

provisions were not fully incorporated in

these rules. For example, the central PESA

states that the gram sabha or panchayat

at the appropriate level shall be consulted

before acquiring land. While the Andhra

Pradesh act has made the provisions to

consult the mandal (block) parishad

before acquiring land, the Jharkhand

act has no provision in this regard. The

Gujarat act provides that taluka panchayats are to be consulted before acquiring

land and the Odisha act mentions that

the district panchayat shall be consulted

before acquiring land.

Third, provisions related to the powers

of gram sabhas regarding land acquisition have been rampantly violated by

many states. For example, in 2006 in

Belar village of Lohandiguda, Bastar,

22

villagers were protesting against their

land being acquired for a steel plant. On

the day set aside for official consent-taking,

a legal provision prohibiting assembly

(Section 144) was imposed on the whole

area to prevent villagers from gathering.

The villagers were then taken one by

one and forced to sign their consent.1

There are many such examples where

land has been acquired through false or

forced consent in Schedule V areas.

Though there have been many shortcomings in the implementation of the

PESA, the agitations and movements that

have strived for its implementation to be

better, particularly the ones led by the

Bharat Jan Andolan and other local

organisations, have created enormous

political awareness in many places. As

mentioned earlier, there are many areas

where the PESA has not been properly

implemented and there are many examples where the state has violated the

spirit of this act. That said, this law has

created enormous political consciousness

in many areas. When Parliament passed

this act, grass-roots organisations had

started what was called pathargadhi (stone

inscription) in many areas of Jharkhand

and Maharashtra. Through this they

inscribed the entirety of the PESA on big

stone pedestals, translating the clauses

in the act into Hindi. This created a lot of

awareness about the provisions of this

law and in many areas people used the

term hamara kanoon (our law) for the

PESA. Interestingly, in Rajasthan and

Jharkhand activists began the stone

inscribing process even before the enactment of the state-level act or the formulation of rules related to PESA. For instance,

during my fieldwork in the Udaipur district of Rajasthan I found that the nongovernmental organisation Aastha and the

Jungle Zameen Andolan established

shilalekh (another term for pathargadhi)

in more than 350 villages of Udaipur

district and declared village self-rule in

these PESA areas. It was a process of

political education for the villagers as they

informed concerned authorities in the

forest department and the block development officer about these actions. In many

villages, on the basis of the central law,

people asserted their rights over common

resources of their village and non-timber forest produce (NTFP) in their traditional Nitstar forests. They stopped the

intervention of local administration and

forest department in their day-to-day activities. Interestingly, since Rajasthan

has not formulated rules till 2011, their

claim regarding village self-rule (gaon

ganarajya) was contestable.

In recent years, many reports The

Report of Expert Group of the Planning

Commission on Development Challenges

in Extremist Affected Areas (2008), the

Sixth Report of the Second Administrative Reforms Commission (2007),

the Balchandra Mungekar Committee

Report (2009), etc have clearly underlined the dismal situation of the implementation of PESA. These and many other

reports prepared by many peoples organisations have recommended that the state

EPW E-books

Select EPW books are now available as e-books in Kindle and iBook (Apple) formats.

The titles are

1. Village Society (ED. SURINDER JODHKA)

(http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00CS62AAW ;

https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/village-society/id640486715?mt=11)

2. Environment, Technology and Development (ED. ROHAN DSOUZA)

(http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00CS624E4 ;

https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/environment-technology-development/

id641419331?mt=11)

3. Windows of Opportunity: Memoirs of an Economic Adviser (BY K S KRISHNASWAMY)

(http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00CS622GY ;

https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/windows-of-opportunity/id640490173?mt=11)

Please visit the respective sites for prices of the e-books. More titles will be added gradually.

febrUARY 21, 2015

vol l no 8

EPW

Economic & Political Weekly

COMMENTARY

should implement PESA in its true spirit

in order to counter the Maoist challenge

to the Indian state.

PESA Amendment Bill

implementation of this act and its rules.

Both the changes are necessary for

making PESA an effective law.

Fourth, the bill repeals Section 5 of

the Principal Act. This states that laws

related to the panchayats in scheduled

areas, which are inconsistent with the

provision of this act should be amended

or repealed by state legislative assemblies within one year from the date on

which this act receives the assent of the

president (Section 5). However, the bill

proposes another section (Section 7) in

lieu of existing Section 5, which says

that any union or state acts dealing with

subjects covered under this amendment

act shall be null and void if they contravene this act, unless brought in conformity within one year of this amendment

taking place (Section 7 of the bill).

Obviously, the bill tries to rectify

many drawbacks and criticisms of the

existing PESA law and it gives more power to the central government to avoid

arbitrary behaviour of many states. Indeed in the matters of land acquisition it

proposes to give more certain powers to

gram sabhas, and proposes to make the

prior informed consent necessary for

any mining or land acquisition.

The MoPR website informs that the PESA

does not specify rule making power or provide a time period by which states have to

frame rules. The language of some sections

of the PESA has been interpreted against

the spirit of the Act. This bill proposed

many important changes in the act. Some

of the vital changes are as follows.

First, it proposes a change in the Section 4(i) of the Principal Act (i e, existing

law) and renumbered it as 4(i) (i). According to the provision of Principal Act, the

gram sabha or panchayat shall be consulted before land acquisition in Schedule V Areas. However, the bill proposes that

prior informed consent of gram sabha or

panchayat should be taken before land

acquisition. It also mandates rehabilitation and sustainable livelihood plan for

the persons affected by projects in the

Schedule V Areas. However, the bill gives

rights to states to determine the processes

of taking prior and informed consent.

Second, Section 4(k) of the Principal

Act provides that the recommendations

of the gram sabha and panchayats at the

appropriate level shall be made mandatory prior to grant of prospecting license

or mining lease for minor minerals

(Section 4(k)) and for grant of concession for exploitation of minor minerals

by auctions (Section 4(l)) in Schedule V

Areas. However, according to the bill the

words prior informed consent would

substitute the word recommendations

and major minerals would also be

included in the purview of the PESA (see

Section 4(k) and 4(l) of the bill).

Third, the bill also intends to insert

two new sections (Sections 5 and 6) in

the PESA. Section 5 of the bill proposes

that both the central government and

the state governments have the powers

to notify rules for the implementation of

the act. However, no provisions of the

state government rules shall be in contravention of the central government

rules (Section 5 of the bill). Section 6 of

the bill empowers the central government

to issue general or special directions to

the state governments for the effective

First, it should be noted that the bill is

not making any provision to secure the

rights of minority groups in the villages

of Schedule V areas. It would lead to a

situation of dominance of the numerically

strong groups and increase the marginalisation of numerically smaller Scheduled

Tribes (STs) and non-ST groups. Second,

considering the experience of the PESA in

the last 16 years, there must be an autonomous body to monitor the implementation

of this act because it has been frequently

violated by government officials. Besides,

centralisation of power, as proposed by

the bill, is not a solution. Third, there have

been many demands for the extension of

Schedule V to newer areas. Such demands

have been made for areas in Kerala, West

Bengal, Karnataka, Rajasthan and other

states, which are tribal-dominated but not

presently covered under Schedule V. The

bill, however, is silent on these crucial

issues. Fourth, as mentioned earlier, the

Bhuria Committee presented another

Economic & Political Weekly

vol l no 8

EPW

febrUARY 21, 2015

Inherent Limitations of the Bill

report which was related to urban areas

under Schedule V. Interestingly a bill

was introduced in Parliament in 2001 in

this regard and it was given to the standing committee on urban development,

which submitted its report in July 2003

and recommended the enactment of this

bill. However, after that session, this bill

was enlisted for debate in every session,

till 2010, but could not get passed or was

debated by Parliament. Though the NAC

also recommended the enaction of a separate law for the urban areas of Schedule V, the bill released for the discussion

is silent on this aspect.

Agenda for the Future

Though both the Congress and the BJP

have expressed their commitment towards

decentralisation of powers, particularly

in tribal areas, the actual behaviour of

these parties has left much to be desired.

While on the one hand, the MoPR released

the PESA amendment bill in December

2013, on the other hand, in the same

month, the Ministry of Environment and

Forests (MoEF), led by Veerappa Moily,

gave clearance to 73 projects without

following the procedure established by

laws like PESA and the Forest Rights Act

(FRA). This dichotomy in policy created

apprehensions about the actual motive

behind releasing the bill for public discussion. Perhaps the United Progressive

Alliance (UPA) government wanted to

use it as an election gimmick. Again, the

present BJP government has accelerated

the process of giving clearance to various

projects. Within 100 days of the formation

of the government, the MoEF has given

environmental clearance to 240 of the

325 projects that had been in limbo as

the previous government slowed down the

process of giving clearances to various

projects due to a variety of reasons. Of

course the PESA is seen as a big obstacle

to those interested in extractive investment in forest areas. One cannot expect

the present government seeking to pass

the amendments to the PESA.

Note

1

Letter from the Struggle Committee of Belar

village, Lohandiguda, Bastar district and the

Dantewada Bhumkal Samiti to the Chairman,

National Commission for Scheduled Tribes,

October 2006.

23

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Legal Reform: Canadian Charterqf Rightsqf FreedomsDocument12 pagesLegal Reform: Canadian Charterqf Rightsqf Freedomsalex davidPas encore d'évaluation

- Slump Sale AgreementDocument35 pagesSlump Sale AgreementSagar Teli100% (1)

- PolicyDoc (2014 9 29 14 14 7 773)Document1 pagePolicyDoc (2014 9 29 14 14 7 773)lexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Tariff Schedule For FY 2016-17Document12 pagesTariff Schedule For FY 2016-17baluu99Pas encore d'évaluation

- 5051853e92b43NCLP GuidelineDocument129 pages5051853e92b43NCLP GuidelinelexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Science Role - Ch4Document10 pagesScience Role - Ch4lexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- AP Socio Eco. 2015 16 FinalDocument319 pagesAP Socio Eco. 2015 16 FinalRaghu Ram100% (1)

- Ethics in EducationDocument4 pagesEthics in EducationlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Marx and Political Theory by Robert J. PrangerDocument19 pagesMarx and Political Theory by Robert J. PrangerlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Assistant - Engineers - Model Question - Paper PDFDocument22 pagesAssistant - Engineers - Model Question - Paper PDFAnonymous jb8Rrf1gPas encore d'évaluation

- AP Reorganisation Bill, 2014Document76 pagesAP Reorganisation Bill, 2014రఘువీర్ సూర్యనారాయణPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Political Theory Philosophy by Mark E WarrenDocument8 pagesWhat Is Political Theory Philosophy by Mark E Warrenlexsaugust100% (1)

- The Need For Adherence To Values in Present Education SystemDocument3 pagesThe Need For Adherence To Values in Present Education SystemlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Science Role - Ch4Document10 pagesScience Role - Ch4lexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Science Role - Ch4Document10 pagesScience Role - Ch4lexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- India Vision2020Document108 pagesIndia Vision2020Bhavin Joshi100% (8)

- Cinema and ModernismDocument7 pagesCinema and ModernismlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Sanctioning Cruelty in THDocument2 pagesSanctioning Cruelty in THlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- VemanaDocument16 pagesVemanaTalluri RambabuPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics of TerrorismDocument9 pagesEthics of TerrorismlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Kinnaur's Curse - Economic and Political WeeklyDocument9 pagesKinnaur's Curse - Economic and Political WeeklylexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Hand Book For Personnel Officers (2013)Document401 pagesHand Book For Personnel Officers (2013)Sandeep Rana100% (1)

- A New Public Policy For A New IndiaDocument3 pagesA New Public Policy For A New IndialexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Upsc AdvtDocument12 pagesUpsc Advtshilpa023_usmsPas encore d'évaluation

- List of 100 Best Novels of All TimesDocument3 pagesList of 100 Best Novels of All TimesMuhammad Usman Khan100% (1)

- Topic 4 Further Reading Kramer Beyond Max WeberDocument21 pagesTopic 4 Further Reading Kramer Beyond Max WeberlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Names of foodstuffs in Indian languagesDocument19 pagesNames of foodstuffs in Indian languagesSubramanyam GundaPas encore d'évaluation

- Conduct Rules, 1964Document100 pagesConduct Rules, 1964lexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics of TerrorismDocument9 pagesEthics of TerrorismlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics of TerrorismDocument9 pagesEthics of TerrorismlexsaugustPas encore d'évaluation

- ICSI UDIN Guidelines for Certification ServicesDocument4 pagesICSI UDIN Guidelines for Certification ServicesSACHIN REVEKARPas encore d'évaluation

- 35 City of Manila Vs Chinese CommunityDocument2 pages35 City of Manila Vs Chinese CommunityClark LimPas encore d'évaluation

- 516A ApplicationDocument6 pages516A ApplicationHassaan KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Ubi Jus Ibi RemediumDocument9 pagesUbi Jus Ibi RemediumUtkarsh JaniPas encore d'évaluation

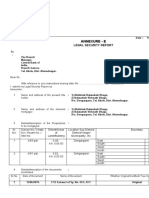

- Annexure - E: Legal Security ReportDocument7 pagesAnnexure - E: Legal Security Reportadv Balasaheb vaidyaPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Vincent Gigante, Vittorio Amuso, Venero Mangano, Benedetto Aloi, Peter Gotti, Dominic Canterino, Peter Chiodo, Joseph Zito, Dennis Delucia, Caesar Gurino, Vincent Ricciardo, Joseph Marion, John Morrissey, Thomas McGowan Victor Sololewski, Anthony B. Laino, Gerald Costabile, Andre Campanella, Michael Realmuto, Richard Pagliarulo, Michael Desantis, Michael Spinelli, Thomas Carew, Corrado Marino, Anthony Casso, 187 F.3d 261, 2d Cir. (1999)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Vincent Gigante, Vittorio Amuso, Venero Mangano, Benedetto Aloi, Peter Gotti, Dominic Canterino, Peter Chiodo, Joseph Zito, Dennis Delucia, Caesar Gurino, Vincent Ricciardo, Joseph Marion, John Morrissey, Thomas McGowan Victor Sololewski, Anthony B. Laino, Gerald Costabile, Andre Campanella, Michael Realmuto, Richard Pagliarulo, Michael Desantis, Michael Spinelli, Thomas Carew, Corrado Marino, Anthony Casso, 187 F.3d 261, 2d Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Redea Vs CADocument3 pagesRedea Vs CAana ortizPas encore d'évaluation

- QatarDocument5 pagesQatarRuth BehailuPas encore d'évaluation

- Treason Laurel Vs Misa Facts: Laurel Filed A Petition For Habeas Corpus. HeDocument29 pagesTreason Laurel Vs Misa Facts: Laurel Filed A Petition For Habeas Corpus. HeBiyaah DyPas encore d'évaluation

- Motion To Revive-FBRDocument3 pagesMotion To Revive-FBRreyvichel100% (2)

- Pecson V CA (1995)Document4 pagesPecson V CA (1995)Zan BillonesPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 173849 Passi V BoclotDocument18 pagesG.R. No. 173849 Passi V BoclotRogie ToriagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nab McqsDocument23 pagesNab McqsIzzat FatimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Board Resolution-Affiliation-Ignacio KO HOA, Inc.Document2 pagesBoard Resolution-Affiliation-Ignacio KO HOA, Inc.Xsche XschePas encore d'évaluation

- NM Civil Guard Filed Verified ComplaintDocument39 pagesNM Civil Guard Filed Verified ComplaintAlbuquerque JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- MLC CertificateDocument1 pageMLC Certificatereenashiv.raiPas encore d'évaluation

- Netaji-Life & ThoughtsDocument42 pagesNetaji-Life & ThoughtsVeeresh Gahlot100% (2)

- 07 GR 211721Document11 pages07 GR 211721Ronnie Garcia Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Echeverria Motion For Proof of AuthorityDocument13 pagesEcheverria Motion For Proof of AuthorityIsabel SantamariaPas encore d'évaluation

- DepEd Isabela City updates on PAAC issues from Jan-Sept 2020Document2 pagesDepEd Isabela City updates on PAAC issues from Jan-Sept 2020Az-Zubayr SalisaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bombay Tenancy and Agricultural Lands Act 1948Document4 pagesBombay Tenancy and Agricultural Lands Act 1948Keith10w0% (1)

- Contract of Lease - 2021Document3 pagesContract of Lease - 2021Liza MelgarPas encore d'évaluation

- Consitutional and Statutory Basis of TaxationDocument50 pagesConsitutional and Statutory Basis of TaxationSakshi AnandPas encore d'évaluation

- Architectural Consultancy AgreementDocument6 pagesArchitectural Consultancy AgreementprashinPas encore d'évaluation

- CIVPRO Mod 1 CompilationDocument33 pagesCIVPRO Mod 1 CompilationKatrina PerezPas encore d'évaluation

- Caragay-Layno V CADocument1 pageCaragay-Layno V CAGel TolentinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Imran Husain Sentencing Memo Oct 2019Document15 pagesImran Husain Sentencing Memo Oct 2019Teri BuhlPas encore d'évaluation

- 7.MSBTE Examination Procedures of Examination Cell and COEDocument5 pages7.MSBTE Examination Procedures of Examination Cell and COEpatil_raaj7234100% (1)