Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Corruption As Discourse of Dis-Enfrenchisement

Transféré par

IOSRjournalTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Corruption As Discourse of Dis-Enfrenchisement

Transféré par

IOSRjournalDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS)

Volume 20, Issue 3, Ver. VII (Mar. 2015), PP 68-71

e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845.

www.iosrjournals.org

Corruption as Discourse of Dis-Enfrenchisement

Florence F. Green and Nicholas N. Siziba

I.

Introduction

This paper looks at corruption as a diversionary, amorphous and neo-colonial idea used by the West to denigrate

African leaders and their achievements after uhuru. "Diversionary" because the term is used as a decoy to

mislead African peoples and their leaders. Instead of striving for material democracy and well-being, the

Africans are set on an anti-corruption crusade, pursuing mirages of transparency, accountability, good

democratic governance as defined for all by the same West. "Good and free" Africans are expected to be seen

and heard chasing or challenging their leaders into joining the anti-corruption crusade. The term corruption

became fashionable with the decolonization of Africa in the 1960s and thus became synonymous with postindependence African leaders and governments. The term is amorphous in that it has no definite meaning and

has different meanings to different people.

II.

The Discourse

The discourse about corruption is dominated by the views of Western governments, their non-governmental

organizations (ngos) and various activist groups like Transparency International Zimbabwe (TI-Z). These see

corruption as endemic to and a feature of African leaders who allow patronage, cronyism, tribalism and

nepotism instead of merit to be the determining factors in the choice of officials to run governance systems.

These factors that constitute the corruption edifice are seen as the malaise explaining the failure of Africans and

their governments to "run modern economies". This failure in turn feeds into another failure to break through the

cycle of poverty. As such, therefore, African leaders are viewed from a negative perspective, seen always

inclined to do harm to their respective communities.

The failures caused by the inherent corruption of African leaders are said to be the root cause of coup de tats in

Nigeria, Ghana, Uganda and other independent African states. "Are said to be" because recent evidence

published by magazines like New African shows the coups had nothing to do with African nationals themselves

seeing their leaders as corrupt. Rather, the coups had all to do with the interests of the Western powers like

America, United Kingdom, Belgium or France. The coups, according to evidence, were staged by Western

intelligence organizations on behalf of their respective governments.

In Zimbabwe, according to one, Chengu (2003:3) an anti-corruption conference in 2002 linked the country's

economic hardships the hoarding and food shortages, fuel crisis, foreign currency shortage and black market

to public sector corruption. The main features of the corruption were "bribes, kickbacks and scratching one's

(sic) in return for favours". The West and its agents see the land reform program as having benefited Mugabe

and his cronies and war veterans only. His government ministers and his relatives are said to be the new

business elite that got that rich through corrupt means. The perception here is that any rich or successful black

business person achieved that status through corruption.

The preferred anti-corruption activities of activists and other Western agents include Western-sponsored

conferences and workshops to conscientise communities about state corruption, demonstrations against

perceived corrupt government officials, disobedience to the "corrupt" state and its agents. National newspapers

have published stories of some of these activists like vowing they cannot accept arrest or prosecution by a police

force or a judiciary led by a "corrupt" commissioner-general and attorney-general respectively.

III.

A Critique of the Western view of Corruption

By identifying, defining and characterizing cronyism, nepotism and tribalism as undesirable manifestations of

African leaders' corruption, the West and its agents denigrate African wisdom as in the chiShona proverb

"Chawawana idya nehama, mutorwa ane hanganwa". In Africa sharing with relatives is natural. Hence one

would be considered strange and viewed with utmost suspicion if they chose to sup and feast with foreigners

only without their own relatives. This is to say that considering one's relatives first say, in hiring workers for

ones business is the norm. Preference of foreigners over one's own can be seen as a product of warped or

DOI: 10.9790/0837-20376871

www.iosrjournals.org

68 | Page

Corruption as Discourse of Dis-Enfrenchisement

corrupted thinking. The result of following such corrupted thinking is to weaken the leader and the institutions

they lead. A leader forced to work with or lead people he does not share much with can only be weaker than one

leading a team of buddies. A system or institution run by warring tribes cannot be expected to be effective. The

English equivalent is "charity begins at home" but it is not seen as promoting nepotism. In the final analysis, a

black entrepreneur or executive that employs or promotes own relatives ahead of non-relatives even if the

relatives qualify for the posts is likely to be investigated and even charged with nepotism, tribalism etc. But

white people have always considered their tribesmen first maybe in line with charity begins at home mantra.

That has never been labeled as corruption or seen as reason for poor performance of their economies or

businesses. In fact the recruits who are usually paid far higher than their black trainers are members of one's

Old Boys' or Fraternity Club or college buddies.

The siNdebele Izandla ziyagezana, imikhombo iyenanana or Ikhoth' eyikhothayo denote reciprocity. According

to the corruption discourse as described above, where Africans are positively returning favours among

themselves, this reciprocity falls under corruption.

Western-sponsored activists have been very active advocating and agitating for an anti-corruption commission,

policies and measures. In Zimbabwe, the anti-corruption crusade has even found its way into the new

constitution adopted in 2013. Corruption as an issue and measures to combat it constitute Sections 254 -7. The

Anti-corruption Commission (ACC) and the National Prosecuting Authority are described as the two

"institutions to combat corruption and crime" and the subject of Chapter 13 of the constitution. But even so, with

the Commission in place, they still continue to complain of "rampant corruption" particularly in the public

sector. It is as if the Anti-Corruption Commission itself is corrupt that is unable to perform!

Responding to the question when exactly the ACC was going to be established and start working, a government

official cautioned the questioner and delegates to the Business Conference at the Zimbabwe International Trade

Fair ( 2013) that the ACC they were clamouring for was most likely going to find not much corruption in public

offices but plenty in the private sector the very sector shouting loudest about corruption.

IV.

African View about Corruption

African scholars like former South African president Thabo Mbeki, Tafataona Mahoso (2014) and Zimbabwe's

2003 Tripartite Negotiating Forum (in association with the National Economic Consultative Forum, NECF)

have countered this Western view of corruption in Africa by characterizing the vice as a process involving a

corrupter or corruptive agent on the one side and a corruptible agent on the other side. Mahoso ( 2014) sees the

Zimbabweans' obsession with fighting corruption in the wake of salary scandals at ZBC and PSMAS as serving

the interests of "corrupted organizations led by corrupted leaders". The idea of these organizations is to divert

Zimbabweans from fighting against Western-imposed sanctions.

The same view came out as part of the "Kadoma Declaration" of the Tripartite Negotiating Forum (NECF

February 2003). The TNF comprising Government, business and labour had met to find common ground and

agree on prices and wages to enable the economy to grow. Perceptions of corruption were identified as a major

component of "country risk" feeding the poor image Zimbabwe had. It was in trying to demystify the risk factor

that the forum came up with the Declaration and analysis of corruption.

In essence the corrupting process is usually initiated by the corrupter finding proper procedures inhibitive and

time-consuming. He/she then approaches systems operatives and offers inducements so as to be allowed to bypass procedures and get away with murder as it were. According to this view the corrupters or corruptive are the

active agents that use and benefit from corruption. But the Western view lays blame on the corrupted or

corruptible Africans. It is like the age-old case of blaming women for prostitution and saying nothing about the

men that constitute the demand side of the equation.

Another difference between the Western and African conceptions of corruption is that the West sees people,

African leaders, as corrupt. But African scholars see systems or institutions like capitalism as corrupt. Under its

mandate the NECF's Anti-Corruption Task Force has, inter alia, the following:

- promote a service culture that mitigates against corrupt practices

- recommend changes in previous laws and practices marginalizing communities

- protect vulnerable members threatened by unfair "standards and practices, etc.

DOI: 10.9790/0837-20376871

www.iosrjournals.org

69 | Page

Corruption as Discourse of Dis-Enfrenchisement

According to this view, it is conditions, under which people live, their practices and institutions that make

people behave the way they do. It is not African peoples or leaders that are corrupt. The benefit of such a view is

that systems or institutions are man-made and can be changed or corrected by people. But people are not manmade and if one is naturally corrupt, not much can be done to correct or change that. In addition, Africans in

Zimbabwe, for instance, have only recently coined a chiShona word uori for corruption. This would demonstrate

that the concept is a new phenomenon to the African. Interestingly, the discourse of corruption in Zimbabwe

comes at a time when the West and their agents are making sustained calls for an end to Mugabes rule. This

suggests that even though words are oft coined to express ones ideational experience (Halliday - ) in this

particular instance it is not the African experience or reality that is expressed but that of the West.

Duodu (2009) writing about promoting corruption in Africa provides evidence showing that Western companies

in their struggles to win competition against rivals routinely pay bribes for contracts in Africa. He cites the case

of Mabey and Johnson, a British engineering company which pleaded guilty to corruption charges laid against it

by the British Serious Fraud Office. The corruption crimes were committed in Ghana. Interestingly, the

company was asked to pay 6.6 million pounds fine to the British state and a mere 658 000 pounds as

"reparations" to Ghana.

The M&J case is typical of many Western companies operating in Africa as Perkins (2005) illustrates. The fact

of the matter is that Western governments, their companies and civil society agents define corruption, bring it

into Africa and benefit from it. After benefiting they become the whistleblowers and reap further benefits from

that too. They are the corrupters that turn the corrupted/corruptible African into the villain thus disenfranchising

him/her. The governments and business communities of Africa are the ones whose reputation is soiled. One

would argue therefore that corruption is an integral part of Western culture that has perfected the art of

managing the vice by turning it from a business threat into an opportunity.

By contrast, Africans seem to have no idea of this lucrative business taking place under their very noses. The

discourse of corruption is hidden from the African maybe because it is alien to ubuntu/unhu. The African does

not understand the hidden agenda behind the discourse of corruption. He most probably is not aware of the

corrupt nature of the activities and institutions of his Western guests unless and until the guests themselves

define their practices as corrupt. And even then the African cannot prosecute these Western corrupters, maybe

because he does not understand the workings of the Western system.

TheRelevance Theory (Sperber and Wilson 1995) reveals that inferences made as a result of discourse become

part of the meaning arrived at. The frequent use of the word corruption in the description of African leaders and

institutions has made that word synonymous with failure. Hence African success cannot be celebrated such as

Zimbabwe's high literacy, the highest in Africa because it is an achievement of a corrupt government.

Another serious form of corruption involves the same Western systems corrupting and destroying other systems.

African thought processes and thoughts are a case in point. Primitive (read: pure, unadulterated, uncorrupted)

African thought is generally considered non-existent or of no consequence. It is not taken seriously until and

unless revised and validated by Westerners and western scholarship. This revisionism kills Africanness and

Africa's unique potential contribution to humanity. What eventually comes out of Africa and is seen as African

is as a result not African at all but a bastardized and corrupted concoction. It is the result of Africans perforce

using un-African tools and methods to craft African thoughts and systems. This dominance of foreign tools and

methods was castigated by the likes of Chinua Achebe and Charles Mungoshi (cited by Gono 2013) who are of

the view that for a solution to be relevant and work in Africa the analysis and processes leading to it must be

African by Africans.

This view of corruption may not be palatable to mainstream (read Western or Westernised) thought; but it is

significant. It tells us that Africans and their institutions are "corrupt" in the sense that genuine ubuntu or

Africanness is actively suppressed and destroyed by corruptive foreigners.

V.

Conclusion

"Corrupt" as a doing word is about spoiling, defiling and preventing systems from operating as expected. People

who corrupt systems or institutions do so for their benefit. In our case these corrupters are the West who

brought the concept to Africa for a purpose. Western companies, NGOs and sponsored activists corrupt African

leaders and institutions to ensure the West benefit at the expense of African masses.

These Westerners use the discourse of corruption to alienate and weaken an identified and targeted African

leader from her/his followers. The same Westerners encourage African people to rebel and overthrow their

DOI: 10.9790/0837-20376871

www.iosrjournals.org

70 | Page

Corruption as Discourse of Dis-Enfrenchisement

corrupt leader and are always assured of Western support and protection if they do. The net result of this is

constant instability as military juntas succeed one another without any of them removing the corruption it said

was the reason for removing the previous regime. This fact supports the argument that claims of corruption in

Africa are just a pretext for those with hidden agenda to get their own hands on African resources.

By alienating followers from their leader the former are also deprived of their identity and recreated as

dependents of the West. The followers cease to identify with their leader, they denounce and despise their

association with "corrupt" leaders. In the end, any achievements made with that leader become a source of

shame. In Zimbabwe, when land redistribution took place those who sympathized with the colonial land

ownership structure disassociated themselves from the whole liberation struggle. They refused to celebrate the

revolution as an achievement. Instead they felt defeated by Mugabe and his cronies.

Of course Africans were corrupted by the whites and their black friends to get into this state of self-denial! By

refusing to be part of victors and choosing to associate with losers, Africans actively dis-empower themselves.

They disenfranchise themselves, perhaps thanks to successful brainwashing from the West. But in the end,

African empowerment and enfranchisement will come, but only when Africans stop the institutionalized

corrupting of things African. Pure or primitive African-ness can offer a lot to humanity (Wutawunashe, 2014)

but only if it can be allowed to exist and operate uncorrupted. For this to happen African-ness may have to

isolate itself from and reject globalizing forces.

References

[1]. Duodu, C. (November 2009) "Who promotes corruption in Africa?" in New African No. 489.

[2]. Gondo K.T. (2013) "An analysis of perceptions of literature in Zimbabwe: In search of an understanding of literature in Zimbabwe" in

Zimbabwe Journal of Teacher Education volume 15 (2).

[3]. Mahoso, T. (2014) Corruption: Destruction of values in The Sunday Mail In-Depth (2 8 February pD2)

[4]. Mahoso T. (2014) "Corruption, sanctions lack of currency and destabilization" in The Sunday Mail In-Depth (23 February 1 March

pD2 ).

[5]. National Economic Consultative Forum (February 2003) Report on deliberations of the TNF at Kadoma Ranch Motel.

[6]. National Economic Consultative Forum (undated) Information file

[7]. Transparency International Zimbabwe (January March 2003) Anti-Corruption Now! Volume 2 Issue 1.

[8]. Wutaunashe, A. (2013) Dear Africa The Call of the African Dream serialized In The Patriot June December 2014

DOI: 10.9790/0837-20376871

www.iosrjournals.org

71 | Page

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Lessons from ADB Transport Projects: Moving Goods, Connecting People, and Disseminating KnowledgeD'EverandLessons from ADB Transport Projects: Moving Goods, Connecting People, and Disseminating KnowledgePas encore d'évaluation

- Corruption As A Manisfestation of Institutional Failure (VC OPARAH, 2009)Document25 pagesCorruption As A Manisfestation of Institutional Failure (VC OPARAH, 2009)vince oparahPas encore d'évaluation

- Trade and Maritime Transport Trends in the PacificD'EverandTrade and Maritime Transport Trends in the PacificPas encore d'évaluation

- A Review of The Works of Anthony GiddensDocument16 pagesA Review of The Works of Anthony Giddensalvinconcha100% (1)

- Reflections on the Debate Between Trade and Environment: A Study Guide for Law Students, Researchers,And AcademicsD'EverandReflections on the Debate Between Trade and Environment: A Study Guide for Law Students, Researchers,And AcademicsPas encore d'évaluation

- Brand ExtensionDocument22 pagesBrand ExtensionAnuranjanSinha100% (3)

- InvestasiDocument77 pagesInvestasiGallyn Ditya ManggalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Supply Chain of Domestic Nickel Ore - Antonius SetyadiDocument34 pagesSupply Chain of Domestic Nickel Ore - Antonius SetyadiВладислав ПлешкоPas encore d'évaluation

- SBM - W1 - Lecture 0 - Course IntroductionDocument8 pagesSBM - W1 - Lecture 0 - Course IntroductionLa VespataxiPas encore d'évaluation

- Macro Economics During Pandemic Covid19Document18 pagesMacro Economics During Pandemic Covid19Tommy Yulian100% (1)

- AoP Tvet ReportDocument26 pagesAoP Tvet ReportEconomic Research Institute for ASEAN and East AsiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 1 - Brand and Brand Management - Part 1 - Ngo BinhDocument16 pagesLecture 1 - Brand and Brand Management - Part 1 - Ngo BinhLa VespataxiPas encore d'évaluation

- STES, Pune Post Graduate Diploma in Management Semester-Iii Course Code - MK-305 Integrated Marketing CommunicationDocument5 pagesSTES, Pune Post Graduate Diploma in Management Semester-Iii Course Code - MK-305 Integrated Marketing CommunicationNoopur AgrawalPas encore d'évaluation

- Mitrais Mining Newsletter Vol 40Document19 pagesMitrais Mining Newsletter Vol 40FauzanWiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Utilization of Digital Marketing For MSME Players As Value Creation For Customers During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument16 pagesUtilization of Digital Marketing For MSME Players As Value Creation For Customers During The COVID-19 PandemicSahira Dody PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 KPPIP - 170921 - Indonesia Infrastructure Investment ForumDocument33 pages1 KPPIP - 170921 - Indonesia Infrastructure Investment Forumdimastri100% (1)

- The External Environment AssessmentDocument70 pagesThe External Environment AssessmentSamuel ChandalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Koordinasi Mitra Pembangunan Untuk Program Percepatan Pembangunan Kesejahteraan Provinsi Papua Dan Papua Barat Menyongsong RPJMN 2020-2024Document26 pagesKoordinasi Mitra Pembangunan Untuk Program Percepatan Pembangunan Kesejahteraan Provinsi Papua Dan Papua Barat Menyongsong RPJMN 2020-2024Saroja AjaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unicef CSR Msia 110713 LowresDocument60 pagesUnicef CSR Msia 110713 LowresParisa MinouchehrPas encore d'évaluation

- Glossary v1.0Document305 pagesGlossary v1.0Rangga DahanaPas encore d'évaluation

- An Updated Guide To Governmental and Non-Governmental Proposals For Reducing Emissions From Deforestation and DegradationDocument71 pagesAn Updated Guide To Governmental and Non-Governmental Proposals For Reducing Emissions From Deforestation and DegradationjonrparsonsPas encore d'évaluation

- FAQ On InvestmentDocument80 pagesFAQ On InvestmentIrka PlayingPas encore d'évaluation

- Leadership Trust and Employee Loyalty in Manufacturing Firms in Port HarcourtDocument11 pagesLeadership Trust and Employee Loyalty in Manufacturing Firms in Port HarcourtIJARP PublicationsPas encore d'évaluation

- EsdDocument7 pagesEsdLenny Verra JosephPas encore d'évaluation

- BRAND MANAGEMENT (SBM) - W2 - Lecture 2 - Chapter 2 - CBBE & Brand Positioning - 092021Document9 pagesBRAND MANAGEMENT (SBM) - W2 - Lecture 2 - Chapter 2 - CBBE & Brand Positioning - 092021La VespataxiPas encore d'évaluation

- Speech by President Uhuru Kenyatta During The National Leadership and Integrity ConferenceDocument4 pagesSpeech by President Uhuru Kenyatta During The National Leadership and Integrity ConferenceState House KenyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Innovation Through CommercializationDocument14 pagesInnovation Through CommercializationPhillipPas encore d'évaluation

- Mining Industrialization - Danilo Israel - PIDS PDFDocument53 pagesMining Industrialization - Danilo Israel - PIDS PDFMartin AxelrotPas encore d'évaluation

- Goldman Sach S NigeriaDocument3 pagesGoldman Sach S NigeriaSeun Oyegunle100% (1)

- APRIL Social Conflicts MappingDocument50 pagesAPRIL Social Conflicts MappingworosssPas encore d'évaluation

- SM HSBCDocument8 pagesSM HSBCRishabh KothariPas encore d'évaluation

- Indonesian Nickel BOOK 2021/2022 Indonesian Nickel BOOK 2021/2022Document2 pagesIndonesian Nickel BOOK 2021/2022 Indonesian Nickel BOOK 2021/2022nugraha kurniawanPas encore d'évaluation

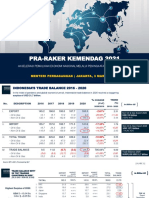

- Pra-Raker Kemendag 2021: Akselerasi Pemulihan Ekonomi Nasional Melalui Peningkatan Peran PerwadagDocument38 pagesPra-Raker Kemendag 2021: Akselerasi Pemulihan Ekonomi Nasional Melalui Peningkatan Peran PerwadagDedy Lampe PRayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Book 8Document63 pagesBook 8IndonesiaPas encore d'évaluation

- REDD 1.3 Stakeholder EngagementDocument40 pagesREDD 1.3 Stakeholder EngagementBobby ThomlinsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Singapore PESTLE ANALYSISDocument7 pagesSingapore PESTLE ANALYSISmonikatattePas encore d'évaluation

- Pacific Region Environmental Strategy 2005-2009 - Volume 1: Strategy DocumentDocument156 pagesPacific Region Environmental Strategy 2005-2009 - Volume 1: Strategy DocumentAsian Development BankPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 5 - Transformational Leadership - Assignment (Nedbank Case)Document4 pagesGroup 5 - Transformational Leadership - Assignment (Nedbank Case)Jahja100% (1)

- Indonesia Japan Economic Partnership Agreement IJEPA Indonesia InvestmentsDocument26 pagesIndonesia Japan Economic Partnership Agreement IJEPA Indonesia InvestmentsMuhamad HafizPas encore d'évaluation

- Myforesight - Malaysian Aesopace BlueprintDocument52 pagesMyforesight - Malaysian Aesopace BlueprintRushdi RahimPas encore d'évaluation

- Insurance Case StudyDocument13 pagesInsurance Case StudyWole OgundarePas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial Policy in KoreaDocument10 pagesIndustrial Policy in KoreaImrul Huda AyonPas encore d'évaluation

- President Uhuru Kenyatta's Speech During The Official Launch of The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Strategic Plan 2013-2018Document5 pagesPresident Uhuru Kenyatta's Speech During The Official Launch of The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Strategic Plan 2013-2018State House KenyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sustainable IndonesiaDocument12 pagesSustainable Indonesiaiconk10Pas encore d'évaluation

- Free Brand Identity Prism Template PowerPoint DownloadDocument2 pagesFree Brand Identity Prism Template PowerPoint DownloadKishore Kintali100% (1)

- Nigeria Advance Variation PartyDocument10 pagesNigeria Advance Variation PartyAll Agreed CampaignPas encore d'évaluation

- Pharma-MD-Cosmetic Registration (HHP21062016) PDFDocument48 pagesPharma-MD-Cosmetic Registration (HHP21062016) PDFReagen Lodeweijke MokodompitPas encore d'évaluation

- Pembangunan Berkelanjutan, Keberlanjutan Perusahaan Dan Ekonomi SirkularDocument21 pagesPembangunan Berkelanjutan, Keberlanjutan Perusahaan Dan Ekonomi Sirkularemil salim100% (1)

- LCDI Report English FINAL PDFDocument162 pagesLCDI Report English FINAL PDFRegi Risman SandiPas encore d'évaluation

- Research in Transportation Economics: Christopher WilloughbyDocument22 pagesResearch in Transportation Economics: Christopher WilloughbynanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bank Syariah Mandiri (BSM) : Via BrivaDocument1 pageBank Syariah Mandiri (BSM) : Via BrivaAnwar FirmansahPas encore d'évaluation

- Insurance in IndonesiaDocument48 pagesInsurance in IndonesiasuksesPas encore d'évaluation

- Surabaya City IndonesiaDocument70 pagesSurabaya City IndonesiaAri WibowoPas encore d'évaluation

- Doing Business in KenyaDocument32 pagesDoing Business in KenyaagrokingPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 - Green Building PDFDocument26 pages01 - Green Building PDFrajiPas encore d'évaluation

- BLOWFIELD Michael - Business and Development - 2012Document15 pagesBLOWFIELD Michael - Business and Development - 2012Sonia DominguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Indonesia LED MarketDocument31 pagesIndonesia LED Marketjavadeveloper lokeshPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of BEPZA in Attracting FDI in BangladeshDocument59 pagesRole of BEPZA in Attracting FDI in BangladeshMd Abdur Rahman Bhuiyan67% (3)

- Chinese MOG Operations in Africa - Conservation InternationalDocument56 pagesChinese MOG Operations in Africa - Conservation InternationalDouglas Ian ScottPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide To Invest in IndonesiaDocument14 pagesGuide To Invest in IndonesiaMeliaMarliantySenjaIraniPas encore d'évaluation

- "I Am Not Gay Says A Gay Christian." A Qualitative Study On Beliefs and Prejudices of Christians Towards Homosexuality in ZimbabweDocument5 pages"I Am Not Gay Says A Gay Christian." A Qualitative Study On Beliefs and Prejudices of Christians Towards Homosexuality in ZimbabweInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Socio-Ethical Impact of Turkish Dramas On Educated Females of Gujranwala-PakistanDocument7 pagesSocio-Ethical Impact of Turkish Dramas On Educated Females of Gujranwala-PakistanInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Attitude and Perceptions of University Students in Zimbabwe Towards HomosexualityDocument5 pagesAttitude and Perceptions of University Students in Zimbabwe Towards HomosexualityInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Review of Rural Local Government System in Zimbabwe From 1980 To 2014Document15 pagesA Review of Rural Local Government System in Zimbabwe From 1980 To 2014International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Extrovert and Introvert Personality in Second Language AcquisitionDocument6 pagesThe Role of Extrovert and Introvert Personality in Second Language AcquisitionInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of The Implementation of Federal Character in Nigeria.Document5 pagesAssessment of The Implementation of Federal Character in Nigeria.International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Proposed Framework On Working With Parents of Children With Special Needs in SingaporeDocument7 pagesA Proposed Framework On Working With Parents of Children With Special Needs in SingaporeInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Visual Analysis of Symbolic and Illegible Indus Valley Script With Other LanguagesDocument7 pagesComparative Visual Analysis of Symbolic and Illegible Indus Valley Script With Other LanguagesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Investigation of Unbelief and Faith in The Islam According To The Statement, Mr. Ahmed MoftizadehDocument4 pagesInvestigation of Unbelief and Faith in The Islam According To The Statement, Mr. Ahmed MoftizadehInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Technologies On Society: A ReviewDocument5 pagesThe Impact of Technologies On Society: A ReviewInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)100% (1)

- Edward Albee and His Mother Characters: An Analysis of Selected PlaysDocument5 pagesEdward Albee and His Mother Characters: An Analysis of Selected PlaysInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- An Evaluation of Lowell's Poem "The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket" As A Pastoral ElegyDocument14 pagesAn Evaluation of Lowell's Poem "The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket" As A Pastoral ElegyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Designing of Indo-Western Garments Influenced From Different Indian Classical Dance CostumesDocument5 pagesDesigning of Indo-Western Garments Influenced From Different Indian Classical Dance CostumesIOSRjournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic: Using Wiki To Improve Students' Academic Writing in English Collaboratively: A Case Study On Undergraduate Students in BangladeshDocument7 pagesTopic: Using Wiki To Improve Students' Academic Writing in English Collaboratively: A Case Study On Undergraduate Students in BangladeshInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Relationship Between Social Support and Self-Esteem of Adolescent GirlsDocument5 pagesRelationship Between Social Support and Self-Esteem of Adolescent GirlsInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Importance of Mass Media in Communicating Health Messages: An AnalysisDocument6 pagesImportance of Mass Media in Communicating Health Messages: An AnalysisInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Madarsa Education in Empowerment of Muslims in IndiaDocument6 pagesRole of Madarsa Education in Empowerment of Muslims in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Apply The Principles of Budgeting Within A MunicipalityDocument67 pagesApply The Principles of Budgeting Within A MunicipalityMarius BuysPas encore d'évaluation

- Articles of Confederation SimulationDocument7 pagesArticles of Confederation Simulationapi-368121935100% (1)

- IMO Publications Catalogue 2005 - 2006Document94 pagesIMO Publications Catalogue 2005 - 2006Sven VillacortePas encore d'évaluation

- The Populist Jurisprudent VR Krishna IyerDocument218 pagesThe Populist Jurisprudent VR Krishna IyerM. BALACHANDARPas encore d'évaluation

- The Failure of The War On DrugsDocument46 pagesThe Failure of The War On DrugsAvinash Tharoor100% (5)

- Contract Tutorial Preparation 4Document4 pagesContract Tutorial Preparation 4Saravanan Rasaya0% (1)

- Deputy RangerDocument3 pagesDeputy Rangerkami007Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Study Viet Cong Use of TerrorDocument85 pagesA Study Viet Cong Use of TerrorCu Tèo100% (1)

- A Project Work On Clean India CampaignDocument10 pagesA Project Work On Clean India CampaignyashPas encore d'évaluation

- CPCLJ2 CHP 2 AssignmentDocument2 pagesCPCLJ2 CHP 2 AssignmentKen KenPas encore d'évaluation

- Digest Gonzales vs. Pennisi 614 SCRA 292 (2010) G.R. No. 169958Document4 pagesDigest Gonzales vs. Pennisi 614 SCRA 292 (2010) G.R. No. 169958KRDP ABCDPas encore d'évaluation

- (HC) Alvis Vernon Rhodes v. Stanislaus County Superior Court - Document No. 6Document5 pages(HC) Alvis Vernon Rhodes v. Stanislaus County Superior Court - Document No. 6Justia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Tourist Visa Document Checklist: More Details Can Be Found at UDI's WebpagesDocument3 pagesTourist Visa Document Checklist: More Details Can Be Found at UDI's WebpagesibmrPas encore d'évaluation

- Attendance Sheet: 2019 Division Schools Press Conference (DSPC)Document1 pageAttendance Sheet: 2019 Division Schools Press Conference (DSPC)John Michael Cañero MaonPas encore d'évaluation

- EssayDocument10 pagesEssayalessia_riposiPas encore d'évaluation

- Indicators For GovernanceDocument16 pagesIndicators For Governanceamirq4Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sen Go EPS - Courtesy Call or MeetingDocument2 pagesSen Go EPS - Courtesy Call or MeetingKrizle AdazaPas encore d'évaluation

- Charles County Code Home Rule ReportDocument32 pagesCharles County Code Home Rule ReportMarc Nelson Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- SADARA ID Card Request Form-001Document1 pageSADARA ID Card Request Form-001Saragadam DilsriPas encore d'évaluation

- Eu Drinking Water Standards PDFDocument2 pagesEu Drinking Water Standards PDFChrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes by NishDocument10 pagesNotes by NisharonyuPas encore d'évaluation

- Resource Finder Financial and Technical Assistance For LocalDocument688 pagesResource Finder Financial and Technical Assistance For LocalRoselle Asis- NapolesPas encore d'évaluation

- Japan's Security Policy: A Shift in Direction Under Abe?: SWP Research PaperDocument35 pagesJapan's Security Policy: A Shift in Direction Under Abe?: SWP Research PaperDev RishabhPas encore d'évaluation

- Right To Information Act 2005Document42 pagesRight To Information Act 2005GomathiRachakondaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prabhunath Singh - WikipediaDocument3 pagesPrabhunath Singh - WikipediaVaibhav SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Washington's Newburgh AddressDocument3 pagesWashington's Newburgh AddressPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Question BankDocument9 pagesQuestion BankAshita NaikPas encore d'évaluation

- Right To EducationDocument21 pagesRight To EducationAshish RajPas encore d'évaluation

- Adtw e 1 2009Document3 pagesAdtw e 1 2009Vivek RajagopalPas encore d'évaluation

- Holman Et Al v. Apple, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 86Document2 pagesHolman Et Al v. Apple, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 86Justia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleD'EverandSomething Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (34)

- Be a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooD'EverandBe a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- The War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionD'EverandThe War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyD'EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,D'EverandBound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (69)

- The Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave TradeD'EverandThe Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave TradeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Shifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in AmericaD'EverandShifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (10)

- The Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartD'EverandThe Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyD'EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (18)

- When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaD'EverandWhen and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (33)

- A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem TragedyD'EverandA Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem TragedyÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (19)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageD'EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (82)

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesD'EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (70)

- Walk Through Fire: A memoir of love, loss, and triumphD'EverandWalk Through Fire: A memoir of love, loss, and triumphÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (72)

- Decolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your PracticeD'EverandDecolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your PracticePas encore d'évaluation

- White Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights EraD'EverandWhite Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights EraÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (43)

- Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its LegacyD'EverandRiot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its LegacyÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (13)

- Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaD'EverandNot a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (37)

- Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to SucceedD'EverandPlease Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to SucceedÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (154)

- Becoming All Things: How Small Changes Lead To Lasting Connections Across CulturesD'EverandBecoming All Things: How Small Changes Lead To Lasting Connections Across CulturesPas encore d'évaluation

- Shame: How America's Past Sins Have Polarized Our CountryD'EverandShame: How America's Past Sins Have Polarized Our CountryÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (86)

- Black Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and SpiritD'EverandBlack Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and SpiritÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (83)

- The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row (Oprah's Book Club Summer 2018 Selection)D'EverandThe Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row (Oprah's Book Club Summer 2018 Selection)Évaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (232)

- Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism 2nd EditionD'EverandAin't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism 2nd EditionÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (382)

- The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy: And the Path to a Shared American FutureD'EverandThe Hidden Roots of White Supremacy: And the Path to a Shared American FutureÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (11)