Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Prediction Clinical Profile To Distinguish Between Systolic and Diastolic Heart Failure in Hospitalized Patients

Transféré par

Vmiguel LcastilloTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Prediction Clinical Profile To Distinguish Between Systolic and Diastolic Heart Failure in Hospitalized Patients

Transféré par

Vmiguel LcastilloDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

European Journal of Internal Medicine 20 (2009) 313 318

www.elsevier.com/locate/ejim

Original article

Prediction clinical profile to distinguish between systolic and diastolic heart

failure in hospitalized patients

Ana Maestrea,, Vicente Gilb , Javier Gallegoa , Miguel Garcac ,

Fernando Garca de Burgosc , Alberto Martn-Hidalgoa

a

Internal Medicine Department. Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Spain

b

Universidad Miguel Hernndez, Spain

Cardiology Section, Internal Medicine Department, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Spain

Received 3 December 2007; received in revised form 12 August 2008; accepted 3 September 2008

Available online 26 October 2008

Abstract

Background: In recent decades, the growing incidence of patients with heart failure who have preserved systolic function, underlines the need to

differentiate between heart failure due to diastolic dysfunction and that due to systolic dysfunction.

Objective: To develop a prediction profile of clinical parameters that enables clinicians to differentiate between patients with systolic and diastolic

heart failure.

Methods: 164 patients admitted for congestive heart failure to the cardiology department of an academic tertiary care hospital, whose left

ventricular systolic and diastolic function had been evaluated echocardiographically and who satisfied the Framingham criteria for heart failure,

were prospectively recruited. All patients answered a questionnaire which included, in addition to other clinical variables, the Framingham criteria.

Results: Patients with diastolic heart failure (61.6%) were more likely to be older, female, and to present left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), with a

lower proportion of smokers, alcohol drinkers, coronary disease, q wave and left bundle branch block (all p b 0.005). The predicting model

obtained on the logistic regression analysis was very significant, with three variables and 72.3% of correct predictions (x2 value = 40,457,

p b 0.001). These three variables, predictors of diastolic as opposed to systolic heart failure, were female sex (OR = 3.546), left ventricle

hypertrophy (OR = 4.011) and absence of coronary disease (OR = 3.547).

Conclusion: Three variables which can be easily evaluated, female sex, left ventricular hypertrophy and presence or absence of coronary disease,

may enable clinicians to differentiate between patients with systolic or diastolic heart failure.

2008 European Federation of Internal Medicine. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Clinical characteristics; Systolic and diastolic dysfunction; Heart failure; Hospitalized patients

1. Introduction

Heart failure is one of the most serious public health

problems in the Western world and most authors consider that

we are facing the greatest cardiovascular epidemic of the 21st

century [1]. This has an increasing impact on the health of the

Corresponding author. Servicio de Medicina Interna, Hospital General

Universitario de Elche, Camino de la Almazara s/n. 03203, Elche, Spain. Tel.:

+34 966679318.

E-mail address: amaestrep@gmail.com (A. Maestre).

population since not only the incidence but also the prevalence

of heart failure is raising, with the resulting increase in

morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs [24].

Approximately 1.52% of the population have heart failure,

and the prevalence rises to 610% in patients over 65 years of

age [2,5,6], in whom it is the main reason for hospital admission

[3,7]. The annual incidence found in the Framingham study rose

from 0.3% in men aged 50 to 59 years to 2.7% in men aged 80

to 89 [6]. Despite medical advances, the mortality is still high

and heart failure is currently the third cause of cardiovascular

mortality in developed countries.

In Spain, there is no data available on the true incidence of

heart failure in the community. With regard to prevalence, a

0953-6205/$ - see front matter 2008 European Federation of Internal Medicine. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2008.09.001

314

A. Maestre et al. / European Journal of Internal Medicine 20 (2009) 313318

population based study from Asturias found a prevalence of 5%,

ranging from less than 1% in patients under 50 years old to 18%

in those over 80 years old [8]. There is more information about

morbidity, based mainly on hospital records and series [9].

Hospital admission for heart failure increased by 47% between

1980 and 1993. This increase was most pronounced in the over

65-year-old population, in which it was the main reason for

admission to hospital and accounted for 5% of all hospital

admissions. Thus, heart failure is also a significant demographic

and healthcare burden for the Spanish population [1].

Few diseases have experienced so many changes in their

epidemiology, physiopathological basis and therapeutic

approach in recent decades as heart failure. One of the main

epidemiological changes is the increasing prevalence of heart

failure in which systolic function is preserved [10,11], as shown

by numerous reports published in recent years, based on the

incidence in the community [7,12], transversal population

studies on prevalence [5,8,1315] or hospital cohorts [1620].

The heterogeneity of published studies, the use of different

diagnostic criteria and cut-off points for left ventricular ejection

fraction, and the fact that left ventricular diastolic function is

rarely evaluated, are only some of the reasons why the

epidemiology of heart failure has not been clearly established.

Although clinical features and physical examination have

failed to consistently discriminate between diastolic and systolic

heart failure in previous studies [21], in clinical practice it could

be useful to be able to differentiate between the two conditions

by means of clinical signs and symptoms.

The objective of this study was to develop a prediction

profile of clinical parameters that could make it possible to

differentiate between patients with systolic heart failure and

those with diastolic heart failure in real healthcare conditions.

2. Patients and methods

This was a prospective observational study. We included all

patients referred to the cardiology section of the University

General Hospital of Elche who were admitted to hospital for

congestive heart failure between 1 June 2002 and 31 May 2003,

whose left ventricular systolic and diastolic function was

evaluated echocardiographically within two days of admission,

and who satisfied the modified Framingham criteria for

congestive heart failure [22]. The criteria advocated by the

European Study Group on Diastolic Heart Failure were used to

measure diastolic dysfunction. This study group proposes a

restrictive approach in which diagnosis of diastolic heart failure

requires a combination of clinical signs and symptoms of heart

failure, preserved or slightly depressed systolic function and

evidence of anomalies in ventricular relaxation, filling or

distension. Systolic dysfunction was based on a left ventricular

ejection fraction of less than 45% [23,24].

Exclusion criteria were those derived from the patient (senile

dementia, being bed-ridden for a long time due to noncardiological problems, cor pulmonale or primary state of

volume overload) and those derived from echocardiography

(poor echogenic window or moderate-severe valvulopathy).

All patients answered a questionnaire which included, in

addition to other sociodemographic and clinical variables, the

Framingham criteria for heart failure (Appendix A.1). Each

patient underwent a thorough physical examination, an

electrocardiogram, chest radiography, specific laboratory tests

and a transthoracic M-mode, 2-dimensional, Doppler echocardiography. The echocardiograms were performed by a trained

cardiologist who determined whether there were valve abnormalities, left ventricular hypertrophy or pulmonary hypertension.

In addition, volumes, left ventricle diameters and a series of

parameters of ventricular dysfunction, such as left ventricular

ejection fraction and the main indexes of diastolic dysfunction,

were calculated by analysing the morphology of the maximum

transmitral flow velocity curve (Appendix A.2).

Univariate tests of statistical significance for differences in

clinical characteristics were performed. Data for continuous

variables were expressed as means and compared using the

Student's t test. Data for categorical or dichotomous variables

were expressed as percentages and compared using the x2 test

or Fisher's exact test. Multiple logistic regression analysis was

used to determine the strength and significance of clinical

characteristics as predictors of normal versus decreased systolic

function. All statistical tests were 2-sided and a p value of 0.05

was selected for the threshold of statistical significance.

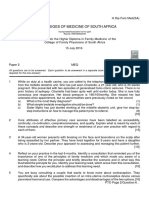

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of patients with systolic heart failure (SHF) and diastolic

heart failure (DHF).

Characteristics

Total

(n = 164)

SHF

(n = 63)

DHF

(n = 101)

P value

Age

Gender

73.02

79 (48.2%)

85 (51.8%)

105 (64.0%)

59 (36.0%)

65 (39.6%)

99 (60.4%)

33 (20.1%)

131 (79.9%)

14 (8.5%)

106 (64.7%)

44 (26.8%)

70.11

43 (68.3%)

20 (31.7%)

35 (55.6%)

28 (44.4%)

22 (34.9%)

41 (65.1%)

14 (22.2%)

49 (77.8%)

9 (14.3%)

31 (49.2%)

23 (36.5%)

74.84

36 (35.6%)

65 (64.4%)

70 (69.3%)

31 (30.7%)

43 (42.6%)

58 (57.4%)

19 (18.8%)

82 (81.2%)

5 (5.0%)

75 (74.2%)

21 (20.8%)

0.003

b0.001

11 (6.7%)

149 (90.9%)

4 (2.4%)

8 (12.7%) 3 (3.0%)

52 (82.5%) 97 (96.0%)

3 (4.8%)

1 (1.0%)

0.014

51 (31.1%)

113 (68.9%)

31 (18.9%)

133 (81.1%)

146.01

82.41

65 (39.8%)

98 (60.2%)

17 (11.1%)

137 (88.9%)

30 (19.2%)

126 (80.8%)

28 (44.4%)

35 (55.6%)

12 (19.0%)

51 (81.0%)

134.79

80.33

13 (21.0%)

49 (79.0%)

11 (18.6%)

48 (81.4%)

17 (27.9%)

44 (72.1%)

0.005

Male

Female

Hypertension

Yes

No

DM

Yes

No

Hyperlipidemia Yes

No

Smoker

Yes

No

Exsmoker

Alcohol

Yes

No

Exdrinker

CD

Yes

No

Anaemia

Yes

No

SBP

DBP

LVH

Yes

No

Q wave

Yes

No

LBBB

Yes

No

23 (22.8%)

78 (77.2%)

19 (18.8%)

82 (81.2%)

157.23

84.49

52 (51.5%)

49 (48.5%)

6 (6.3%)

89 (93.7%)

13 (13.7%)

82 (86.3%)

0.094

0.412

0.690

0.004

1.000

b0.001

0.225

b0.001

0.032

0.037

DM: Diabetes mellitus; CD: coronary disease; SBP: systolic blood pressure (mm Hg);

DBP: diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg); LVH: Left ventricular hypertrophy; LBBB:

Left bundle branch block

A. Maestre et al. / European Journal of Internal Medicine 20 (2009) 313318

315

Analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software,

version 12.0.

Table 3

Final predicting model for diastolic dysfunction in patients admitted to hospital

with heart failure.

3. Results

Variable

Odds ratio

CI of 95%

Female sex

LVH

Absence of coronary disease

3.546

4.011

3.547

(1.7247.297)

0.001

(1.9168.399)

b0.001

(1.7127.347)

b0.001

x2 value = 40,457, p b 0.001

Correctly classified: 72.3%

The final sample consisted of 164 patients, of whom 85 were

women (51.8%) and 79 men (48.2%), with a mean age of

73 years.

With regard to the prevalence of classical vascular risk

factors, 105 patients (64.0%) were hypertensive, 65 (39.6%)

were diabetic, 33 (20.1%) had hyperlipidemia, 14 (8.5%) were

active smokers, and 44 (26.8%) ex-smokers. In addition, 11

patients (6.7%) had alcohol abuse and 61 (37.2%) were obese.

Regarding main associated co-morbidities, coronary disease

was present in 31.1% of the population studied, whereas chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease and anaemia were both present

in 18.9%.

Echographic data showed systolic dysfunction in 63 (38.4%)

and diastolic dysfunction in 101 (61.6%) of the 164 patients.

The clinical characteristics of the study patients are shown in

Table 1. Patients with diastolic heart failure were older

(p = 0.003), more likely to be women (p b 0.001), with higher

levels of systolic blood pressure (p b 0.001), more likely to have

left ventricle hypertrophy (p b 0.001) and with a lower

proportion of smokers (p = 0.004), alcohol abuse (p = 0.014),

coronary disease (p = 0.005), total left bundle branch block

(p = 0.037) and q waves (p = 0.032) compared with patients with

systolic failure.

Table 2

Distribution of the Framingham criteria in patients with systolic heart failure

(SHF) and diastolic heart failure (DHF).

Framingham criteria

Total (n = 164) SHF (n = 63) DHF (n = 101) p value

PND

147 (89.6%)

17 (10.4%)

34 (21.0%)

128 (79.0%)

135 (82.3%)

29 (17.7%)

144 (88.3%)

19 (11.7%)

19 (11.6%)

145 (88.4%)

52 (37.7%)

86 (62.3%)

27 (16.6%)

136 (83.4%)

111 (67.7%)

53 (32.3%)

32 (19.5%)

132 (80.5%)

164 (100%)

0 (0%)

42 (30.7%)

95 (69.3%)

62 (38.0%)

101 (62.0%)

43 (26.4%)

120 (73.6%)

Yes

No

NVD

Yes

No

Crackles

Yes

No

Cardiomegaly

Yes

No

APE

Yes

No

S3-Gallop

Yes

No

HJR

Yes

No

Ankle oedema

Yes

No

Nocturnal cough Yes

No

Dyspnoea

Yes

No

Hepatomegaly

Yes

No

PE

Yes

No

Tachycardia

Yes

No

56 (88.9%)

7 (11.1%)

14 (22.2%)

49 (77.8%)

51 (81.0%)

12 (19.0%)

59 (95.2%)

3 (4.8%)

5 (7.9%)

58 (92.1%)

26 (46.4%)

30 (53.6%)

12 (19.0%)

51 (81.0%)

39 (61.9%)

24 (38.1%)

11 (17.5%)

52 (82.5%)

63 (100%)

0 (0%)

19 (35.8%)

34 (64.2%)

19 (30.6%)

43 (69.4%)

17 (27.4%)

45 (7.6%)

91 (90.1%)

10 (9.9%)

20 (20.2%)

79 (79.8%)

84 (83.2%)

17 (16.8%)

85 (84.2%)

16 (15.8%)

14 (13.9%)

87 (86.1%)

26 (31.7%)

56 (68.3%)

15 (15.0%)

85 (85.0%)

72 (71.3%)

29 (28.7%)

21 (20.8%)

80 (79.2%)

101 (100%)

0 (0%)

23 (27.4%)

61 (72.6%)

43 (42.6%)

58 (57.4%)

26 (25.7%)

75 (74.3%)

0.798

0.844

0.834

0.043

0.320

0.107

0.522

0.233

0.688

0.343

0.138

0.856

PND: Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea; NVD: Neck vein distention; APE: Acute

pulmonary oedema; HJR: Hepatojugular reflux; PE: Pleural effusion.

p value

LVH: Left ventricular hypertrophy.

Logistic regression analysis.

The presence of the Framingham clinical criteria was

compared in both groups by means of a univariate analysis

(Table 2). The distribution of the Framingham criteria only

showed significant differences in cardiomegaly, which was

more frequent in the group of systolic heart failure (p = 0.043).

The prediction model obtained on the multiple logistic

regression analysis (Table 3) was very significant (p b 0.001),

and made it possible to distinguish between patients with

diastolic heart failure and systolic heart failure using three

variables with a good prediction potential (correct classification

in 72.3% of cases). These three variables, predictors of diastolic

as opposed to systolic heart failure, were female sex

(OR = 3.546), left ventricular hypertrophy (OR = 4.011) and

absence of coronary disease (OR = 3.547).

4. Discussion

In recent decades, the growing incidence of heart failure with

preserved systolic function underlines the need to differentiate

between heart failure due to diastolic dysfunction and that due

to systolic dysfunction [25]. In most of the published studies,

both groups are defined using the same echocardiographic

parameterleft ventricular ejection fractionwithout specifically evaluating the indexes of diastolic function. This is the

main reason why diastolic heart failure is not referred to as such

but rather as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

[11,16,17].

Very few studies objectively evaluate diastolic function

[14,15] and all that do, except for one recently published study

that assess this parameter in hospitalized patients [26], have

been performed in a community setting. In European population, we found only one study by the German group of Fischer

et al. which evaluated the prevalence of left ventricular diastolic

dysfunction in the community using echocardiography [13].

Our study differs from others in that it includes only patients

with heart failure confirmed on echocardiography, and determines

not only the ejection fraction but also diastolic ventricular

dysfunction. In the present study, more than half (61.6%) of the

individuals had diastolic heart failure. Patients with diastolic heart

failure were older, there was a greater proportion of women, more

likely to have left ventricular hypertrophy, fewer smokers and

alcohol drinkers, less coronary artery disease and fewer q waves

or total left bundle branch block, than in patients with systolic

heart failure. In addition, patients with diastolic heart failure were

more likely to have arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus,

316

A. Maestre et al. / European Journal of Internal Medicine 20 (2009) 313318

although the differences did not attain the significance expected.

With regard to the distribution of the Framingham criteria, no

significant differences were found except for cardiomegaly.

However, the presence of third sound and hepatomegaly did tend

to be greater in the systolic dysfunction group (46.4%), as has

been reported in prior studies [27,28].

When all the previously mentioned characteristics are

combined, in our sample, female sex, left ventricular hypertrophy

and the absence of coronary artery disease explain almost 75% of

the variability between the diagnosis of diastolic and systolic heart

failure.

Most of these data correspond to a large extent with those

published so far, although some differences should be pointed

out. In our study, the proportion of patients with diastolic heart

failure was 61.6% versus 38.4% with systolic heart failure. This

greater prevalence of patients with diastolic heart failure may be

due to the fact that one of our exclusion criteria was the

existence of moderate or severe valvulopathies, since their

presence prevent the indexes of diastolic dysfunction from

being correctly determined [11,16,29]. However, in other

studies which simply evaluated whether left ventricular ejection

fraction was depressed or preserved, such patients could be

included. Since most of these patients had systolic dysfunction,

this group of patients could increase in number [18,28]. In

addition, the advanced age of our patients might have

contributed to the greater prevalence of diastolic dysfunction.

The first study performed in Spain to evaluate the percentage

of patients with altered or preserved systolic dysfunction and to

describe the clinical characteristics of both groups was carried

out in Santiago de Compostela [9]. In this study, investigators

included all the patients admitted to a cardiology department for

congestive heart failure who fulfilled the Framingham clinical

criteria and whose left ventricular systolic function had been

evaluated. Therefore, the criteria for inclusion were very similar

to ours, except that both groups were defined using a single

echocardiographic parameter, left ventricular ejection fraction,

and without specifically evaluating the diastolic dysfunction

indexes. They reported a mean age of 66.7 years, with a

predominance of men (58.5%) and the presence of arterial

hypertension in 52.2% of the cases, followed by coronary

disease in 45.4%. Fewer than 30% of the patients had preserved

systolic function. When comparing these results with those of

our study, in the former the patients were younger, there were

more men, a lower prevalence of arterial hypertension and more

coronary disease, as well as a smaller proportion of patients with

diastolic heart failure (28.8%). The authors attribute the

differences between their results and those published in other

studies to the fact that, in their hospital, elderly patients with

heart failure not thought to be secondary to coronary disease are

not referred to the cardiology service [9]. It is possible that these

elderly patients, who are controlled by other services, make up

the population sub-group most often described in other studies,

with a predominance of women and greater prevalence of

arterial hypertension. Very recently, this same group published

another study which was an extension of the first [28], over a

study period of 10 years, with results somewhat different. The

mean age in this case was higher (69.4 years versus 66.7 years),

with a higher proportion of patients with preserved systolic

function (39.8% versus 28.8%), although the rest of clinical

characteristics remained the same.

Comparing our results with those reported in other hospital

cohort studies carried out abroad, many similarities are found.

The first retrospective studies showed a clear predominance of

women with heart failure and normal systolic function, which

was consistent throughout the various sub-groups of patients

[18,27]. McDermott et al. published a retrospective review and

provided a prediction model with which they obtained a correct

classification (76%) very similar to ours (72.3%). As in our

study, patients with heart failure and normal left systolic

function were older, more often women and less likely to have a

history of coronary artery disease [27]. Unfortunately, left

ventricular diastolic dysfunction was not assessed again.

Thomas et al. evaluated the usefulness of the clinical history,

physical examination, electrocardiogram and chest X-ray in

differentiating between patients with normal and depressed

systolic function (specific diastolic indexes were not evaluated

in this study). Patients with preserved systolic function were

generally female, older and obese, with higher levels of diastolic

and systolic blood pressure; whereas tachycardia, clinical

symptoms of angina pectoris and alcohol consumption were

more frequent in patients from the other group. On multivariate

analysis, sex and tachycardia were the only clinical variables

showing significant association [16].

The first multicentre prospective study to characterize the clinical profile, hospital stay and treatment of heart failure with normal

ejection fraction concluded that the majority of patients were

women (73%), older than the men in this group and there was a high

percentage of arterial hypertension (78%), left ventricular hypertrophy (82%), diabetes mellitus (46%), and obesity (46%) [17].

Recently, results from two other studies in hospital setting with

similar results have been published. Owan et al. carried out a

retrospective study in patients hospitalized for heart failure to

define secular trends in the prevalence and survival of heart failure

with preserved ejection fraction [26]. These authors did use

specific echocardiographic parameters for diastolic dysfunction

and found that 53% of patients had reduced ejection fraction and

47% normal ejection fraction. In the other study carried out by

Bhatia et al. [20], of the 2802 patients admitted for heart failure,

31% had an ejection fraction above 50%. These patients were

more likely to be older, female, and had a significantly higher

incidence of hypertension and atrial fibrillation than those with

depressed ejection fraction. However, complications, rates of readmission and mortality were similar in both groups.

Finally, potential limitations to our study should be acknowledged to facilitate the interpretation of the results. In order to avoid

any possible measurement bias, extreme care was taken when performing the echocardiography. All the echocardiograms were

performed by an experienced cardiologist using the same equipment. However, we realise that there are a series of circumstances

such as atrial fibrillation, tachycardia or poor echographic window

that can make it difficult to evaluate left ventricular function.

Another measurement bias could arise from the reliability and

consistency of the interviewer when performing the anamnesis and

physical examination of the patients. All the interventions were

A. Maestre et al. / European Journal of Internal Medicine 20 (2009) 313318

Hyperlipidemia

Smoker

Alcohol intake

Coronary artery disease

Anaemia

Symptoms:

Dyspnoea

Acute pulmonary oedema

Nocturnal cough

Dyspnoea on exertion

Physical examination:

Weight

Height

Blood pressure

Heart rate

Temperature

Neck vein distension

Crackles

S3 gallop

Hepatojugular reflux

Ankle oedema

Hepatomegaly

Radiological data:

Cardiomegaly

Pleural effusion

Electrocardiographical data:

Rhythm

Left ventricular hypertrophy

Q wave

Left bundle branch block

Laboratory tests:

Serum cholesterol (mg/dl)

Fibrinogen (mg/dl)

Serum triglycerides (mg/dl)

Haemoglobin (g/dl)

Serum creatinine (mg/dl)

Partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) (mm Hg)

made by the same observer, who underwent training in taking these

measurements in clinical practice. The study might also be limited

by the fact that only echocardiography was used to diagnose diastolic abnormalities, since echographic diastolic indexes are dependent on the cardiac frequency, after-load and pre-load, or the time it

is performed [13]. However, the alternative techniques are invasive

or require exposure to radioisotopes, which means they are not

applicable to all the population. Another limitation could be the use

of a cut-off point of 45% for the left ventricular ejection fraction as

the only index of normal systolic function, since regional or slightly

impaired systolic dysfunction could be overlooked. We used this

value because it was recommended in the Spanish and European

guidelines we decided to use when starting the study [23,24]. A final

limitation could be that treatment and medication of the enrolled

patients was not considered and that results apply to a tertiary

referral centre and may not be applicable to other populations.

In conclusion, in this study three variables that may be easily

assessed, female sex, left ventricular hypertrophy and absence

of coronary disease, enable us to differentiate between patients

with systolic or diastolic heart failure. This clinical predicting

profile of diastolic heart failure is the first to be obtained in a

European population admitted to hospital for heart failure.

Although clinical assessment and non-invasive cardiac

investigations (chest radiography or electrocardiography) are

not a substitute for an objective evaluation of left ventricular

dysfunction, these results may help to make an initial differential

diagnosis between systolic and diastolic heart failure, especially

regarding primary healthcare or non-cardiological specialities

that depend on cardiologists to carry out echocardiograms. The

results could so enhance the clinician's confidence in making a

diagnosis of diastolic heart failure and confirm the characteristics of these patients in the hospital setting.

In the future, it could be of clinical worth to reliably

distinguish these two populations clinically up-front to stratify

treatment strategies appropriately.

5. Learning points

Although clinical features and physical examination have

failed to discriminate consistently between diastolic and

systolic heart failure by clinical assessment in previous

studies, in clinical practice it could be useful to differentiate

between these two conditions.

In this study, three variables easily evaluated: female sex, left

ventricular hypertrophy and presence or absence of coronary

disease, enabled clinicians to differentiate between patients

with systolic or diastolic heart failure.

Appendix A

A.1. Questionnaire

Clinical variables:

Age

Gender

Hypertension

Diabetes mellitus

317

2. Echographic diagnostic criteria for left ventricular

dysfunction

1)

2)

-

Systolic dysfunction:

Depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) b45%.

Diastolic dysfunction:

Evidence of abnormal diastolic function indexes:

Slow early left ventricular filling:

On Doppler echocardiography of mitral diastolic flow, in the

apical projection of four cavities:

E/A b 1 and DT N 220 ms, in patients under 50 years of age

E/A b 0.5 and DT N 280 ms, in patients over 50 years of age

In Doppler flow velocity of pulmonary veins:

S/D N 1.5, in patients under 50 years of age.

S/D N 2.5, in patients over 50 years of age.

Slow isovolumetric left ventricular relaxation:

IVRT N 92 ms, in patients under 30 years of age.

IVRT N 100 ms, in patients between 30 and 50 years of age.

318

A. Maestre et al. / European Journal of Internal Medicine 20 (2009) 313318

IVRT N 105 ms, in patients over 50 years of age.

S/D: ratio of systolic to diastolic pulmonary venous flow

velocity; this was not determined due to the difficulties involved

in this technique.

Diastolic ventricular dysfunction required the presence of

one or more of the above criteria.

Normal or mildly reduced ejection fraction (LVEF N 45%)

References

[1] Conthe P. De la hipertensin arterial a la insuficiencia cardaca. Cundo y

cmo iniciar tratamiento. Rev Clin Esp 2002;202(Extr2):916.

[2] Cowie MR, Mosterd A, Wood DA, Deckers JW, Poole-Wilson PA, Sutton

GC, et al. The epidemiology of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1997;18

(2):20825.

[3] Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Guallar-Castilln P, Banegas JR, del Rey J. Trends

in hospitalizations and mortality for heart failure in Spain, 19801993. Eur

Heart J 1997;18:17719.

[4] Massie BM, Shah NB. Evolving trends in the epidemiologic factors of

heart failure: rationale for preventive strategies and comprehensive disease

management. Am Heart J 1997;133:70312.

[5] Mosterd A, Hoes A, Bruyne M, Deckers JW, Linker DT, Hofman A, et al.

Prevalence of heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction in the general

population. The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 1999;20:44755.

[6] Ho K, Pinsky J, Kannel W, Levy D. The epidemiology of heart failure: the

Framingham study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22(Supl A):6A13A.

[7] Cowie MR, Fox K, Metcalfe C, Thompson SG, Coats AJ, Poole-Wilson

PA, et al. Hospitalization of patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J

2002;23:87785.

[8] Cortina A, Reguero J, Segovia E, Rodriguez Lambert JL, Cortina R, Arias

JC, et al. Prevalence of heart failure in Asturias (a region in the north of

Spain). Am J Cardiol 2001;87:14179.

[9] Varela Romn A, Gonzalez Juanatey JR, Basante P, Trillo R, Garca-Seara

J, Martinez-Sande JL, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of

hospitalised inpatients with heart failure and preserved or reduced left

ventricular ejection fraction. Heart 2002;88:24954.

[10] Dauterman K, Massie B, Gheorghiade M. Heart failure associated with

preserved systolic function: a common and costly clinical entity. Am Heart

J 1998;135:S310319.

[11] Hogg K, Swedberg K, McMurray J. Heart failure with preserved left

ventricular systolic function. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics and

prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:31727.

[12] Senni M, Tribouilloy C, Rodeheffer R, Jacobsen SJ, Evans JM, Bailey KR,

et al. Congestive heart failure in the community. A study of all

incident cases in Olmsted County, Minnesota, in 1991. Circulation

1998;98:22829.

[13] Fischer M, Baessler A, Hense H, Hengstenberg C, Muscholl M, Holmer S,

et al. Prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in the community.

Results from a doppler echocardiographic-based survey of a population

sample. Eur Heart J 2003;24:3208.

[14] Redfield M, Jacobsen S, Burnett J, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer

RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the

community. JAMA 2003;289:194202.

[15] Bursi F, Weston S, Redfield M, Jacobsen S, Pakhomov S, Nkomo V, et al.

Systolic and diastolic heart failure in the community. JAMA

2006;296:220916.

[16] Thomas JT, Kelly R, Thomas SJ, Stamos TD, Albasha K, Parrillo JE, et al.

Utility of history, physical examination, electrocardiogram and chest

radiograph for differentiating normal from decreased systolic function in

patients with heart failure. Am J Med 2002;112:43745.

[17] Klapholz M, Maurer M, Lowe A, Messineo F, Meisner JS, Mitchell J,

Kalman J, et al. Hospitalization for heart failure in the presence of a normal

left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:14328.

[18] Masoudi F, Havranek E, Smith G, Fish RH, Steiner JF, Ordin DL, et al.

Gender, age, and heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic

function. J Am coll Cardiol 2003;41:21723.

[19] Cleland JG, Swedberg K, Follath F, Komajda M, Cohen-Solal A, Aguilar

JC, et al. The EuroHeart Failure survey programmea survey on the

quality of care among patients with heart failure in Europe. 1: patient

characteristics and diagnosis. Eur Heart J 2003;24(5):44263.

[20] Bhatia R, Tu J, Lee D, Austin P, Fang J, Haouzi A, et al. Outcome of heart

failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl

J Med 2006;355:2609.

[21] Vasan R, Benjamin E, Levy D. Prevalence, clinical features and prognosis

of diastolic heart failure: an epidemiologic perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol

1995;26:156574.

[22] McKee P, Castelli W, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of

congestive heart failure: The Framingham Study. N Engl J Med

1971;285:14416.

[23] European Study Group on Diastolic Heart Failure of the European Society

of Cardiology. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure. Eur Heart J

1998;19:9901003.

[24] Navarro-Lpez F, de Teresa E, Lpez-Sendn JL, Castro-Beiras A. Guas

del diagnstico, clasificacin y tratamiento de la insuficiencia cardaca y

del shock cardiognico. Informe del Grupo de trabajo de Insuficiencia

Cardaca de la Sociedad Espaola de Cardiologa. Rev Esp Cardiol

1999;52(Supl 2):154.

[25] Vasan R, Levy D. Defining diastolic heart failure: a call for standardized

diagnostic criteria. Circulation 2000;101:211821.

[26] Owan T, Hodge D, Herges R, Jacobsen S, Roger V, Redfield M. Trends in

prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N

Engl J Med 2006;355:2519.

[27] McDermott MM, Feinglass J, Sy J, Gheorghiade M. Hospitalized

congestive heart failure patients with preserved versus abnormal left

ventricular systolic function: clinical characteristics and drug therapy. Am

J Med 1995;99:62935.

[28] Varela Romn A, Grigorian L, Barge E, Bassante P, de la Pea MG,

Gonzalez-Guanatey JR. Heart failure in patients with preserved and

deteriorated left ventricular ejection fraction. Heart 2005;91(4):48994.

[29] Zile M, Gaasch W, Carroll J, Feldman M, Aurigemma G, Schaer G, Ghali

J, Liebson P. Heart failure with a normal ejection fraction: is measurement

of diastolic function necessary to make the diagnosis of diastolic heart

failure? Circulation 2001;104:77982.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- VaricoceleDocument10 pagesVaricoceleDenny SetyadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexander DisciplineDocument240 pagesAlexander DisciplineOctavian Tavi100% (1)

- AnginaDocument18 pagesAnginabertouwPas encore d'évaluation

- Research ArticleDocument8 pagesResearch ArticleMiguelPas encore d'évaluation

- EuroHeart Failure Survey II A Survey On Hospitalized Acute Heart Failure PatientsDocument12 pagesEuroHeart Failure Survey II A Survey On Hospitalized Acute Heart Failure PatientsEffika PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Art 3A10.1007 2Fs00125 012 2579 0Document9 pagesArt 3A10.1007 2Fs00125 012 2579 0Sabdiah Eka SariPas encore d'évaluation

- ERC Epidemiology of Cardiac Arrest in EuropeDocument19 pagesERC Epidemiology of Cardiac Arrest in EuropeNindy MaharaniPas encore d'évaluation

- THREAT Helps To Identify Epistaxis Patients Requiring Blood TransfusionsDocument6 pagesTHREAT Helps To Identify Epistaxis Patients Requiring Blood TransfusionswitariPas encore d'évaluation

- 129 Full PDFDocument7 pages129 Full PDFHerlina ApriliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Article 1 MMDocument12 pagesArticle 1 MMNoureenHusnaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Catheter Ablation For Atrial Fibrillation: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesCatheter Ablation For Atrial Fibrillation: Original ArticleGavin WinkelPas encore d'évaluation

- International Journal of Scientific Research: General MedicineDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Scientific Research: General MedicineTriple APas encore d'évaluation

- Characteristics of Patients With Venous Thromboembolism and Atrial Fibrillation in VenezuelaDocument5 pagesCharacteristics of Patients With Venous Thromboembolism and Atrial Fibrillation in VenezuelaDhedy DheyzPas encore d'évaluation

- Order ID 3416232.edited - EditedDocument5 pagesOrder ID 3416232.edited - Editedngunyijohn001Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ejhs2901 0887Document8 pagesEjhs2901 0887Syawal DragonballPas encore d'évaluation

- Pharm D (PB) 2 YEAR 2020-2021: Under The Guidance of GuideDocument41 pagesPharm D (PB) 2 YEAR 2020-2021: Under The Guidance of Guidesufiya fatimaPas encore d'évaluation

- MINOCA STEMI Manuscript 0Document19 pagesMINOCA STEMI Manuscript 0wellaPas encore d'évaluation

- 24 Rudrajit EtalDocument6 pages24 Rudrajit EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 464 FullDocument11 pages464 FullgunnasundaryPas encore d'évaluation

- The Shortfall in Long-Term Survival of Patients With Repaired Thoracic Orabdominal Aortic Aneurysms Retrospective CaseeControl Analysis Ofhospital Episode StatisticsDocument9 pagesThe Shortfall in Long-Term Survival of Patients With Repaired Thoracic Orabdominal Aortic Aneurysms Retrospective CaseeControl Analysis Ofhospital Episode StatisticsJeffery TaylorPas encore d'évaluation

- Coronary Surgery in Europe: Comparison of The National Subsets of The European System For Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation DatabaseDocument4 pagesCoronary Surgery in Europe: Comparison of The National Subsets of The European System For Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation DatabaseDannia Riski ArianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Managementul Acut Al TVC La Cei in Tratament Cu AntiagregantDocument21 pagesManagementul Acut Al TVC La Cei in Tratament Cu AntiagregantDrHellenPas encore d'évaluation

- Pregunta Del EstudioDocument7 pagesPregunta Del EstudioMarco RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure 2017 The American Journal of MedicineDocument11 pagesDiabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure 2017 The American Journal of MedicineAlina PopaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hipertrofia VD en HTADocument8 pagesHipertrofia VD en HTAgustavo reyesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Prognostic Role of Anemia in Heart Failure PatientsDocument7 pagesThe Prognostic Role of Anemia in Heart Failure PatientsAnonymous rprdjdFMNzPas encore d'évaluation

- Characteristics and Contemporary Outcome Ventricular Septal Rupture Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction: ClinicalDocument8 pagesCharacteristics and Contemporary Outcome Ventricular Septal Rupture Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction: ClinicalJorge PalazzoloPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal Pre-Proof: Canadian Journal of CardiologyDocument45 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: Canadian Journal of CardiologyANISA RIFKA RIDHOPas encore d'évaluation

- JournalDocument11 pagesJournalewetPas encore d'évaluation

- 1201 FullDocument7 pages1201 FullDavy JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Nejmoa040532 Acut MitralDocument8 pagesNejmoa040532 Acut MitralYuliasminde SofyanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Pulmonary Oedema Clinical Characteristics, Prognostic Factors, and In-Hospital ManagementDocument10 pagesAcute Pulmonary Oedema Clinical Characteristics, Prognostic Factors, and In-Hospital ManagementaegonblackPas encore d'évaluation

- NEJMra 040291Document12 pagesNEJMra 040291alamajorPas encore d'évaluation

- Carotid JCPSP WaDocument4 pagesCarotid JCPSP Washakil11Pas encore d'évaluation

- Arteritis TakayasuDocument7 pagesArteritis TakayasuGina ButronPas encore d'évaluation

- Premature Coronary Artery Disease Among Angiographically Proven Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease in North East of Peninsular MalaysiaDocument10 pagesPremature Coronary Artery Disease Among Angiographically Proven Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease in North East of Peninsular MalaysiaLili YaacobPas encore d'évaluation

- Pontine HgeDocument4 pagesPontine HgemohamedsmnPas encore d'évaluation

- Castle AfDocument11 pagesCastle AfgustavoPas encore d'évaluation

- Endocarditis in The Elderly: Clinical, Echocardiographic, and Prognostic FeaturesDocument8 pagesEndocarditis in The Elderly: Clinical, Echocardiographic, and Prognostic FeaturesMehdi285858Pas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction On Clinical Outcome in Hypertrophic CardiomyopathyDocument9 pagesEffect of Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction On Clinical Outcome in Hypertrophic CardiomyopathyAstrid Noviera IksanPas encore d'évaluation

- De Novo Acute Heart Failure and Acutely Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure PDFDocument14 pagesDe Novo Acute Heart Failure and Acutely Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure PDFEffika PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Therapeutic Implications: Short QT Syndrome: Clinical Findings and DiagnosticDocument8 pagesTherapeutic Implications: Short QT Syndrome: Clinical Findings and DiagnosticNITACORDEIROPas encore d'évaluation

- Low Systemic Vascular ResistanceDocument7 pagesLow Systemic Vascular ResistanceMuhammad BadrushshalihPas encore d'évaluation

- Ima 1Document9 pagesIma 1larasatiwibawaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison Between Type-2 and Type-1 Myocardial Infarction: Clinical Features, Treatment Strategies and OutcomesDocument8 pagesComparison Between Type-2 and Type-1 Myocardial Infarction: Clinical Features, Treatment Strategies and OutcomesDewi Cahya FitriPas encore d'évaluation

- European J of Heart Fail - 2006 - Cokkinos - Efficacy of Antithrombotic Therapy in Chronic Heart Failure The HELAS StudyDocument5 pagesEuropean J of Heart Fail - 2006 - Cokkinos - Efficacy of Antithrombotic Therapy in Chronic Heart Failure The HELAS Studysebastián orejuelaPas encore d'évaluation

- The UP-Philippine General Hospital Acute Coronary Events at The Emergency Room Registry (UP PGH-ACER)Document11 pagesThe UP-Philippine General Hospital Acute Coronary Events at The Emergency Room Registry (UP PGH-ACER)Camille MalilayPas encore d'évaluation

- J Thromres 2012 05 016Document6 pagesJ Thromres 2012 05 016Alexandra RosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cardiovascular Prevention Measures After An Gender Differences in The Implementation ofDocument7 pagesCardiovascular Prevention Measures After An Gender Differences in The Implementation ofSeppo LehtoPas encore d'évaluation

- AorticDisten&DD CardiologyDocument6 pagesAorticDisten&DD CardiologyAlexandru CozmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure: Michael Lehrke, MD, and Nikolaus Marx, MDDocument11 pagesDiabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure: Michael Lehrke, MD, and Nikolaus Marx, MDMUFIDAH VARADIPAPas encore d'évaluation

- Chest: High Prevalence of Undiagnosed Airfl Ow Limitation in Patients With Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument8 pagesChest: High Prevalence of Undiagnosed Airfl Ow Limitation in Patients With Cardiovascular DiseaseRoberto Enrique Valdebenito RuizPas encore d'évaluation

- Heart Failure Thesis PDFDocument6 pagesHeart Failure Thesis PDFafknwride100% (2)

- Diastolic Function Is A Strong Predictor of Mortality in Patients With Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument6 pagesDiastolic Function Is A Strong Predictor of Mortality in Patients With Chronic Kidney DiseasehanifahrafaPas encore d'évaluation

- DNB Vol25 No2 142Document7 pagesDNB Vol25 No2 142Apsopela SandiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- Cardiac Surgery in Octogenarians: Peri-Operative Outcome and Long-Term ResultsDocument9 pagesCardiac Surgery in Octogenarians: Peri-Operative Outcome and Long-Term ResultsRumela Ganguly ChakrabortyPas encore d'évaluation

- CardioDocument10 pagesCardiobursy_esPas encore d'évaluation

- Development and Validation of A Risk Score For Predicting Death in Chagas' Heart DiseaseDocument8 pagesDevelopment and Validation of A Risk Score For Predicting Death in Chagas' Heart Diseaserandom guyPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal Pone 0172745 PDFDocument13 pagesJournal Pone 0172745 PDFselamat parminPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinico-Pathological Atlas of Cardiovascular DiseasesD'EverandClinico-Pathological Atlas of Cardiovascular DiseasesPas encore d'évaluation

- Microcirculation in Cardiovascular DiseasesD'EverandMicrocirculation in Cardiovascular DiseasesEnrico Agabiti-RoseiPas encore d'évaluation

- Asma - NelsonDocument22 pagesAsma - NelsonVmiguel LcastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome: Post-Transplant Diabetes MellitusDocument4 pagesDiabetology & Metabolic Syndrome: Post-Transplant Diabetes MellitusVmiguel LcastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Antitumor Effects of Octreotide LAR, A Somatostatin AnalogDocument2 pagesAntitumor Effects of Octreotide LAR, A Somatostatin AnalogVmiguel LcastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Wendy K. Fujioka, Robert A. CowlesDocument3 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Wendy K. Fujioka, Robert A. CowlesVmiguel LcastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Self-Medication in Older Urban Mexicans: An Observational, Descriptive, Cross-Sectional StudyDocument2 pagesSelf-Medication in Older Urban Mexicans: An Observational, Descriptive, Cross-Sectional StudyVmiguel LcastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- JNC 8 PDFDocument14 pagesJNC 8 PDFAlan NophalPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On Knowledge Regarding Prevention of Cervical CancerDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Knowledge Regarding Prevention of Cervical Cancerea8p6td0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mate Rio VigilanceDocument4 pagesMate Rio VigilanceilyasPas encore d'évaluation

- Foot Ankle Scenario IndiaDocument12 pagesFoot Ankle Scenario IndiaKirubakaran Saraswathy PattabiramanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 13 Bahasa InggrisDocument5 pagesChapter 13 Bahasa InggrisGildaPas encore d'évaluation

- jURNAL Anc tERPADUDocument8 pagesjURNAL Anc tERPADUcathyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethical Theories in Health and Social CareDocument5 pagesEthical Theories in Health and Social CareRameeza AbdullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Overview of Measles DiseaseDocument3 pagesOverview of Measles DiseaseLighto RyusakiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Modern Management of Incisional HerniasDocument9 pagesThe Modern Management of Incisional HerniasAnonymous oh1SyryiPas encore d'évaluation

- H Dip Fam Med (SA) Past Papers - 2016 2nd Semester 24-1-2017Document2 pagesH Dip Fam Med (SA) Past Papers - 2016 2nd Semester 24-1-2017matentenPas encore d'évaluation

- Cast Metal Restorations 2021Document56 pagesCast Metal Restorations 2021nandani kumariPas encore d'évaluation

- Jopte SPG14Document97 pagesJopte SPG14Sylvia LoongPas encore d'évaluation

- Insulin in GDM Ver 2.0Document47 pagesInsulin in GDM Ver 2.0Akash GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- NW Centenary Pub PDFDocument28 pagesNW Centenary Pub PDFRazaCreciaLastrillaMenesesPas encore d'évaluation

- Obs and Gynae OSPEDocument79 pagesObs and Gynae OSPEKitty GracePas encore d'évaluation

- Candidiasis Opportunistic Mycosis Within Nigeria: A ReviewDocument6 pagesCandidiasis Opportunistic Mycosis Within Nigeria: A ReviewUMYU Journal of Microbiology Research (UJMR)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bedouin TribesDocument38 pagesBedouin TribesAnonymousFarmerPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. Taha A Khan CVDocument4 pagesDr. Taha A Khan CVTaha Akhtar KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lang and Loe (1972) - The Relationship Between The Width of Keratinized Gingiva and Gingival Health PDFDocument5 pagesLang and Loe (1972) - The Relationship Between The Width of Keratinized Gingiva and Gingival Health PDFCinthia CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- I. LearningsDocument5 pagesI. LearningsMarie Kelsey Acena MacaraigPas encore d'évaluation

- ACF-USA 2004 Annual ReportDocument14 pagesACF-USA 2004 Annual ReportAction Against Hunger USAPas encore d'évaluation

- Family Nursing Care Plan CriteriaDocument7 pagesFamily Nursing Care Plan CriteriaAnonymous K99UIf1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Uncoordinated ContractionsDocument23 pagesUncoordinated ContractionsjoyceexallowPas encore d'évaluation

- HidrosefalusDocument13 pagesHidrosefalusmelvinia.savitri19Pas encore d'évaluation

- Oral Litchen PlanusDocument5 pagesOral Litchen PlanusWulan Ambar WatyPas encore d'évaluation

- Health-Care Workers' Occupational Exposures To Body Fluids in 21 Countries in Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument17 pagesHealth-Care Workers' Occupational Exposures To Body Fluids in 21 Countries in Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisgusdePas encore d'évaluation

- Caregiving Strategies For Older Adults With Delirium Dementia and Depression PDFDocument220 pagesCaregiving Strategies For Older Adults With Delirium Dementia and Depression PDFLucia CorlatPas encore d'évaluation

- An Intervention of 12 Weeks of (V)Document16 pagesAn Intervention of 12 Weeks of (V)Isabel MarcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Maternal and Child Health ProgrammesDocument55 pagesMaternal and Child Health ProgrammesArchana Sahu100% (1)