Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Colour Foods Jagadeesh 1 PDF

Transféré par

Dilip GuptaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Colour Foods Jagadeesh 1 PDF

Transféré par

Dilip GuptaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2004, 39, 125131

Type, extent and use of colours in ready-to-eat (RTE) foods

prepared in the non-industrial sector a case study

from Hyderabad, India

Padmaja R. Jonnalagadda,1* Pratima Rao,2 Ramesh V. Bhat2 & A. Nadamuni Naidu2

1 Food and Drug Toxicology Research Centre, National Institute of Nutrition, Jamai-Osmania (PO), Hyderabad 500 007,

AP, India

2 National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, AP, India

(Received 28 September 2001; Accepted in revised form 28 April 2003)

Summary

The type and extent of colours added to ready-to-eat (RTE) foods prepared in the nonindustrial sector of India was investigated. Of the 545 RTE foods analysed, 90% contained

permitted colours, 2% contained a combination of permitted and non-permitted colours

and 8% contained only non-permitted colours. However in RTE foods with permitted

colours, 73% exceeded 100 ppm, as prescribed by the Prevention of Food Adulteration

Act of India, and 27% were within the prescribed levels. Among the permitted colours,

tartrazine was the most widely used colour followed by sunset yellow. The maximum

concentration of colours was detected in sweet meats (18 767 ppm), non-alcoholic

beverages (9450 ppm), miscellaneous foods (6106 ppm) and hard-boiled sugar confectioneries (3811 ppm). Among the non-permitted colours found, rhodamine was most

commonly used. Some of the foods, such as savouries and miscellaneous foods like sugar

coated aniseed and almond milk, are not supposed to contain colours as per the Prevention

of Food Adulteration Act, but were found to contain colours.

Keywords

Colourants, food regulations, orange G, rhodamine, sunset yellow, tartrazine.

Introduction

In India, like most developing countries, both the

industrial and non-industrial sectors are engaged in

food processing activities. The industrial sector is

subjected to quality checks whereas the nonindustrial sector, by its very nature, is outside the

realm of quality checks and statutory controls.

Rapid urbanization has meant that the associated

sociological change is impacting on the life-style of

a large segment of the population. This is resulting

in enhanced demand for pre-packaged and precooked ready-to-eat (RTE) foods. The annual

production of RTE foods in the industrial sector

of India is 345 411 tonnes (Anon., 1995). However,

RTE foods produced in the non-industrial sector,

including bakery products like bread, biscuits,

*Correspondent: Fax: 91 40 27019074;

e-mail: nin@ap.nic.in

2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

rusks, cakes, and other RTE foods such as potato

chips, are two to three times that produced in the

industrial sector (Agarwal, 1990, 1994; Alagh,

1990; Chowdhry, 1990; Sharma & Sharma, 1994).

It has been suggested that the consumption of such

foods could sometimes lead to harmful eects

(NIN, 1994, annual report). Colour additives are

known to be one of the causes of such harmful

eects. The variety of synthetic colours, developed

in the middle of the nineteenth century, are a

reliable and economical method of partly restoring

the original shade of the foods (that would

otherwise be virtually dull) and also act as a

competitive substitute to the natural colourants

which are more expensive, less stable, and possess

lower tinctorial power (Achaya, 1984; Rao, 1990).

The use of synthetic colours by the food processing

industry is increasing because they are considered

as important adjuncts.

The use of permitted and non-permitted colours

in foods in India has been reported previously

125

126

Usage of colours in RTE foods P. R. Jonnalagadda et al.

(Khanna et al., 1973, 1985, 1986; Chakravarti,

1988; Biswas et al., 1994; Babu & Shenolikar,

1995; Dixit et al., 1995; Singh, 1997; Bhat &

Mathur, 1998; Mathur, 2000), as has the fact that

the use of non-permitted colours are known to

cause adverse eects in experimental animals

(Prasad & Rastogi, 1982; Wess & Archer, 1982;

Singh et al., 1987) and in humans (Power et al.,

1969; Chandra & Nagaraja, 1987; Sachadeva

et al., 1992). Subsequently, the use of non-permitted colours in RTE foods and other items of daily

consumption have been subjected to regulatory

scrutiny involving the judiciary (Sinha, 1988).

Repeated exposure to even the permitted synthetic

colours is hazardous (Lockey, 1977; Achaya,

1984). The Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) has

been dened as the amount of a substance that can

be consumed everyday throughout the lifetime of

an individual without any appreciable health

eects (JECFA, 1996). The ADI of erythrosine

was reduced from 2.5 to 0.1 mg kg)1 body-weight,

as it produced eects on thyroid function in shortterm studies in rats (Larsen, 1991). It has also been

reported that the consumption of a particular

brand of aniseed (saunf), having very high levels of

ponceau 4R, produced symptoms of glossitis of

the tongue in children (NIN, 1994, annual report).

Based on toxicological evaluation of synthetic

food colours the Central Committee for Food

standards (CCFS, India) has been constantly

updating the food regulations. As a part of these

regulations, certain colours such as amaranth and

Fast red E were banned and the reduction of the

synthetic food colour limit from 200 to 100 ppm in

all foods except in canned foods, jams and jellies

has been recommended. Dierent countries permit

dierent synthetic food colours. The USA permits

seven, including Fast red (which is prohibited for

use in India), Iran and Australia, thirteen each and

in the European Union (EU) sixteen synthetic

permitted food colours are permitted. European

countries have been harmonizing the regulations,

and most of the controls on colourings in food

stem from EU directives. Each country is attempting to review these controls by surveillance work.

India permits addition of eight colours, viz.

erythrosine, carmoisine, ponceau 4R, tartrazine,

sunset yellow, brilliant blue FCF, Fast green FCF,

and indigo carmine up to specied food items. In

India, the Prevention of Food Adulteration (PFA)

Act, which lays down specications on the addition of additives to foods, was amended in 1995

(Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 1995) and

permitted the use of the above-mentioned synthetic food colours in or upon food items

(Table 1).

Data on permitted synthetic food colours and

the levels to which they can be used, was used to

study, within the outlets of Hyderabad city, the

variety of RTE foods sold, the RTE foods with

added colours and the quality, quantity and extent

of use of colours in RTE foods produced by the

non-industrial sector.

Materials and methods

A total of 145 outlets, viz. supermarkets (twentythree), sweetmeat stalls (forty-ve), wholesale

markets (fteen), retail outlets selling only confectioneries and other coloured RTE foods such as

deep-fried snack foods, fun foods for children like

sugar toys, coloured synthetic powders, etc. (ten),

bakeries (twenty-one), fast food centres (six) and

small vendors (twenty-ve) were surveyed to nd

out the type and extent of RTE foods sold in the

city of Hyderabad, using a pre-tested pro forma. A

total of 545 samples of coloured food items were

purchased from the 145 outlets mentioned above.

Extraction of synthetic dyes from coloured

RTE foods

Five to ten grams of the coloured food was ground

thoroughly and colours extracted using three

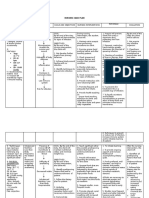

Table 1 Permitted synthetic food colours can be used in the

following foods as per the PFA Act

Food items

1. Ice-cream, milk lollies, frozen dessert, flavoured milk,

yoghurt, ice- cream mix powder

2. Non-alcoholic carbonated and non-carbonated

ready-to-serve synthetic beverages including syrups,

sherbets, fruit bar, fruit beverages, fruit drinks, synthetic

soft drink concentrates

3. Biscuits, including biscuit wafer, pastries, cakes,

confectionery, thread candies, sweets, savouries

(dal moth, mongia, phul gulab, sago papad, dal biji)

4. Peas, strawberries and cherries in hermatically sealed

containers, preserved or processed papaya, canned tomato

juice, fruit syrup, fruit squash, fruit cordial, jellies, jam,

marmalade, candied crystallised or glazed fruits

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2004 39, 125131

2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Usage of colours in RTE foods P. R. Jonnalagadda et al.

dierent methods. Mostly the samples were

extracted to identify colours by using a column

chromatography method and wool dyeing methods (Toteja et al., 1990). For certain categories of

RTE foods such as sweetmeats, bakery foods and

confectioneries, a modied method suggested by

Biswas et al. (1994) was used. The extracted

coloured solutions were spotted onto Whatman

no. 1 chromatography paper strips together with

authentic standard colours. The samples were

separated for colours using dierent solvent systems. The standard colours supplied by Bush

Boak and Allen (Chennai, India) and S.D. Fine

Chemicals Ltd (Mumbai, India) were subjected to

purity checks (Walford, 1984).

Qualitative analysis was performed by comparing the relative factor, i.e. ratio between the

distance moved by the spot of the food colour

and the distance moved by the solvent front of the

separated colours with those of standard colours,

which were prepared in water (1 mg mL)1). The

quantitative analysis of the single colours in water

solutions was done directly by measuring the

absorbance values. Blends of colours were separated by paper chromatography and the separated

colours were then eluted from paper into water

and their absorbance was measured against standard colours using a Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer (Lambda-1: C632-000; Perkin Elmer,

Norwalk, CT, USA). The values were tabulated

and calculated to express the quantity of colour in

micrograms per gram (lg mL)1 in the case of

liquid samples) of the preparation (Ranganna,

1986).

Results

A variety of RTE food products with added

colours sold in the city of Hyderabad is given in

Table 2. Most of the RTE foods sold in the

market were coloured and it is dicult to nd an

RTE food without any colour. Some of the RTE

non-vegetarian preparations, like chicken 65,

chicken manchuria and chicken gravy, were also

found to be coloured. Of the 545 coloured RTE

foods analysed, 32% were sweetmeats, 40% were

Table 2 Variety of RTE foods with added colours sold in the city of Hyderabad

Food Groups

Food items

Bakery items

Biscuits (both plain cream), wafers, rusks, cakes (sponge plum and fruit),

bread, buns, and pastries in different flavours

Lollypops in various forms like cherries, raspberries, grapes, apples, etc.;

mints, golis, gems, toffees, sugar toys in various forms of birds, candies,

fruit bars, mouth fresheners like peppermints; fun foods like chewing gums,

bubble gums, syrupy balls, confectioneries in the shape of oil seeds such as

groundnut with some gifts like rings, etc.

Bengal gram pulse flour preparations like laddus, Mysorepaks. Black gram pulse

flour preparations like jangris. Preparations with refined wheat flour:

jilebis, khajoor. Milk-based preparations: burfies and pedas, milk product-based

preparations: rasagolla, chum chum, gulabjamoon, basundi. Sweets made in the

shape of beetel leaf, cereal-based preparations like wheat halwas, halwas made

of vegetables such as pumpkin, carrot, with ghee and sugar, puffed rice

and flaked rice preparations such as laddus.

Rice flour and bengal gram pulse-based preparations such as murukus*.

Refined wheat flour preparations such as chekodi*. Bengal gram flour

preparations such as sev*, bujiya, boondi*. Fried pulses such as bengal gram

and green gram pulses.

Non-carbonated and carbonated synthetic syrups, sherbets, juices, synthetic

soft drink concentrates, badam (almond) milk*, lassi* (buttermilk, yoghurt)

Synthetic* coloured powders in different tastes like mango (aamchuran),

katmit powder, sugar* coated coloured saunf (aniseed), coconut gratings,

crushed ice, fresh green peas, soups, sauces, chicken 65, chicken manchuria,

chicken gravy, fried groundnuts*, biryani (a rice preparation), ice candies,

ice creams. Cherries, crystallized or glazed fruits such as tuiti frooti.

Hard-boiled sugar

confectioneries

Sweetmeats

Savouries

Non-alcoholic beverages

Miscellaneous foods

*Foods which are not supposed to contain added colours as per the PFA Act.

2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2004, 39, 125131

127

128

Usage of colours in RTE foods P. R. Jonnalagadda et al.

Table 3 List of permitted and non-permitted food colours

Permitted colours

Non-permitted colours

Tartrazine

Sunset yellow FCF

Ponceau 4R

Carmoisine

Erythrosine

Brilliant blue FCF

Rhodamine

Orange G

Amaranth

Fast red

Metanil yellow

hard-boiled sugar confectioneries, 21% were

miscellaneous foods and 7% were non-alcoholic

beverages. Among the 545 coloured RTE foods

analysed, 90% were found to contain permitted

colours, while 8% contained non-permitted colours, and 2% contained a combination of

permitted and non-permitted colours. Forty-ve

RTE foods had non-permitted colours and 11

had a combination of permitted and non-permitted colours. These include seven sweetmeats,

thirty-six hard-boiled sugar confectioneries and

thirteen miscellaneous foods. Non-permitted colours were absent in all the non-alcoholic beverages. The permitted and non-permitted colours

are listed in Table 3. Of the 90% of the

permitted coloured RTE foods analysed, 54%

contained tartrazine (in blend with brilliant blue

FCF), 31% had sunset yellow (in blend with

carmosine, ponceau 4R, and tartrazine), 19%

had brilliant blue FCF, 10% had carmosine, 8%

had ponceau 4R and 3% had erythrosine. The

distribution of the permitted colours in the

various food groups is given in Table 4. It was

observed that tartrazine and sunset yellow were

the most common permitted colours used. The

overall pattern of the frequency of the permitted

colours in a variety of coloured RTE foods

indicated that tartrazine in blend with brilliant

Permitted colours

Sweetmeats

Hard-boiled sugar

confectioneries

Tartrazine

Sunset yellow

Ponceau 4R

Carmosine

Erythrosine

Brilliant blue FCF

63.4

33.7

5.1

6.3

Nil

16.0

48.4

27.9

6.8

11.0

5.9

21.0

blue FCF is the most widely used colour,

followed by sunset yellow (in blend with carmosine, ponceau 4R, and erythrosine), carmosine,

ponceau 4R, brilliant blue FCF (in blend with

tartrazine) and erythrosine. There seemed to be

slight variations in the frequency of the colours

when the individual food categories are considered. It was tartrazine followed by sunset yellow,

brilliant blue FCF, carmosine, and ponceau 4R

in sweetmeats, hard-boiled sugar confectioneries,

bakery foods and miscellaneous foods, while in

non-alcoholic beverages it was tartrazine followed by sunset yellow, carmosine, ponceau 4R,

brilliant blue FCF and erythrosine. The use of

erythrosine was totally absent in sweetmeats and

miscellaneous foods, and the green colours

Indigo carmine and Fast green FCF, were not

detected in any of the coloured RTE foods

analysed in the present study (Table 4). Of the

90% of the RTE foods having permitted colours,

73% were found to exceed the 100 ppm level

prescribed by PFA, while only 27% were well

within the prescribed levels. The individual status

of each permitted colour within and above the

prescribed levels are given in Table 5. It was

observed that the limit was exceeded most for

ponceau 4R, followed by sunset yellow, tatrazine, carmoisine, erythrosine and brilliant blue

FCF. Ten per cent of the non-permitted colours

(including the 2% blended with permitted colours) present in the coloured RTE foods were

rhodamine, orange G, amaranth, Fast red and

metanil yellow. The distribution of non-permitted colours in coloured RTE foods indicated that

rhodamine followed by orange G, Fast red,

amaranth and metanil yellow are the colours

used. The pattern of distribution varied when the

individual food categories are reported (Table 6).

Miscellaneous

foods

Non-alcoholic

beverages

52.7

28.6

11.6

9.8

Nil

22.3

53.8

48.7

15.4

20.5

2.6

12.8

Table 4 Distribution of permitted

food colours in RTE foods (%)

The total percentage for each food category is more than 100 because some foods had

combinations of two colours.

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2004 39, 125131

2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Usage of colours in RTE foods P. R. Jonnalagadda et al.

Table 5 Number of RTE foods (expressed as percentage)

having colours below and above permissible levels

Permitted colours

<100 ppm

>100 ppm

Tartrazine

Sunset yellow

Ponceau 4R

Carmosine

Erythrosine

Brilliant blue FCF

31.5

28.5

23.3

37.0

53.3

64.8

68.5

71.5

76.7

63.0

46.7

35.2

Table 6 Distribution of non-permitted food colours in a

variety of coloured RTE foods (%)

Hard-boiled

Non-permitted

sugar

Miscellaneous

colours

Sweetmeats confectioneries foods

Rhodamine

Amaranth

Orange G

Fast red

Metanil yellow

Nil

14.3

85.7

Nil

Nil

36.1

25.0

22.2

36.1

13.9

30.7

15.4

Nil

38.5

15.4

The total percentage for hard-boiled sugar confectioneries is

more than 100 as they are combinations of permitted colours.

Discussion

The present study shows permitted colours were

used in the majority of the RTE foods. However,

the quantities of the colours detected ranged

from 101 to 18 767 ppm (higher or much higher

than the level of 100 ppm prescribed by Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 1995). Biswas

et al. (1994) reported the use of permitted colours

in RTE foods exceeding the then permissible level

of 200 ppm, upto a maximum of 730 ppm. In the

present study, the highest concentrations were

found in sweetmeats (18 767 ppm), non-alcoholic

beverages (9450 ppm), miscellaneous foods

(6106 ppm) and hard-boiled sugar confectioneries

(3811 ppm).

Reports on earlier studies showed that nonpermitted colours were used in wide range of RTE

foods (Khanna et al., 1973, 1985, 1986, 1987;

Chakravarti, 1988; Biswas et al., 1994; Dixit et al.,

1995). In contrast, in the present study, the use of

non-permitted colours was found to be considerably less than previously as it was detected in only

10% of the RTE foods. This could be due to the

awareness of the manufacturers to the hazards of

non-permitted colours but could also be because

2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

of the stringent action taken by the regulatory

authorities.

It was also observed in the present study that

the RTE foods shown in Table 2, although not

supposed to contain any added colours as per the

PFA Act, contained colours. Although the PFA

Act was amended in 1995 and the use of colours

restricted to specic items like biscuits, thread

candies, sweets, dalmoth, fruit juice, ice cream, etc.

a variety of RTE foods still contained synthetic

food colours (Table 2), thereby implying that the

implementation of food regulations needs to be

much more vigorous.

It was interesting to note that although the

Prevention of Food Adulteration Act (1995)

permits eight colours to be added to specic

foods, only six colours were used, i.e. tartrazine,

sunset yellow (either individual or in blend with

other permitted colours such as carmosine, ponceau 4R, erythrosine and brilliant blue FCF),

carmosine, ponceau 4R, erythrosine and brilliant

blue FCF. However, brilliant blue FCF was

mostly used in blends with tartrazine to give a

green shade to food items such as fresh green peas,

fried green peas, milk-based sweetmeat preparations, bakery foods like pastries and cakes, ice

cream, ice candies and synthetic syrups, etc. The

use of individual green colours such as Fast green

FCF and Indigo carmine were not found in any of

the coloured RTE foods in the present study.

Of the six permitted colours analysed, in the

present study, tartrazine and sunset yellow (either

in blend or individual with other permitted synthetic colours) seem to be the most popular and

often used. Similar observations were made by

Khanna et al., 1973, 1985, 1986; Chakravarti,

1988; Biswas et al., 1994; Dixit et al., 1995;

Mathur, 2000). The overall pattern of usage of

colours, in the present study, indicates that, of the

six synthetic permitted colours found to be used,

there was less common usage than expected.

Hence, there is a pressing need to revise the number

of permitted synthetic colours to be added to foods.

The predominant use of the two colours mentioned

previously could be attributed to the traditional

practice of the manufacturers to try to match the

colour of the basic raw materials such as bengal

gram dhal preparations, or as a substitute to the

natural colours like turmeric, or to attain yellow

colour in foods with added pineapple avour, and

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2004, 39, 125131

129

130

Usage of colours in RTE foods P. R. Jonnalagadda et al.

for orange to substitute the natural colours like

saron (Achaya, 1994). The use of non-permitted

colours was found to be more in hard-boiled sugar

confectioneries, bakery foods and miscellaneous

foods than in the rest of the food groups.

It can be concluded from the present investigation that although the prevalent use of nonpermitted colours has been considerably reduced,

the level or concentration of synthetic permitted

colours was noticeably higher than the specications prescribed under the PFA Act. A closer

vigilance and stricter enforcement is necessary.

Also, a better awareness is necessary for enhancing the quality of coloured RTE foods prepared

in the non-industrial sector on the part of the

State food health authorities. In addition, a

relentless campaign needs to be undertaken to

improve the awareness amongst consumers of the

unscrupulous use of synthetic food colours,

particularly concerning vulnerable consumers

such as children.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Kamala Krishnaswamy, Director,

National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), for the keen

interest shown by her in the study. The nancial

support provided by the Council of Scientic and

Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India (for

the Senior author, PRJ), and also the Ministry of

Food Processing, New Delhi (for the second

author, PR), is gratefully acknowledged.

References

Achaya, K.T. (1984). Everyday Indian Processed Foods. Pp.

154162. Delhi: National Book Trust.

Achaya, K.T. (1994). Indian Food a Historical Companion.

Pp. 140151. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Agarwal, S.R. (1990). Prospects for small scale biscuit

industry in the nineties. Indian Food Industry, 9, 1921.

Agarwal, S.R. (1994). Current and future trends of biscuit

industry in India. Indian Food Industry, 13, 3237.

Alagh, K.S. (1990). Biscuit industry in India future

scenario. Indian Food Industry, 9, 18.

Anon. (1995). Food Processing Industries In India Investment Opportunities. Pp. 98105. New Delhi: Ministry of

Food Processing Industries.

Babu, S. & Shenolikar, I. (1995). Health and nutritional

implications of food colours. Indian Journal of Medical

Research, 102, 245249.

Bhat, R.V. & Mathur, P. (1998). Changing scenario of food

colours in India. Current Science, 74, 198202.

Biswas, G., Sarkar, S. & Chatterjee, T.K. (1994). Surveillance on articial colours in food products in Calcutta

and adjoining areas. Journal of Food Science and

Technology, 31, 6667.

Chakravarti, R.N. (1988). A simple test for butter yellow,

a carcinogenic oil soluble dye in edible and cosmetic

materials. Journal of the Institution of Chemists, 60,

206.

Chandra, S.S. & Nagaraja, T. (1987). A food poisoning

outbreak with chemical dye an investigation report.

Medical Journal of Armed Forces India, 43, 291293.

Chowdhry, S. (1990). Bread industry in India looking

ahead. Indian Food Industry, 9, 2223.

Dixit, S., Pandey, R.C., Das, M. & Khanna, S.K. (1995).

Food quality surveillance on colours in eatables sold in

rural markets of Uttar Pradesh. Journal of Food Science

and Technology, 32, 373376.

JECFA, (1996). Summary of Evaluations Performed by the

Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives,

19561996. FAO/IPCS/WHO. Geneva: WHO.

Khanna, S.K., Singh, G.B. & Singh, S.B. (1973). Nonpermitted colours in food and their toxicity. Journal of

Food Science and Technology, 10, 3336.

Khanna, S.K., Singh, G.B. & Dixit, A.K. (1985). Use of

synthetic dyes in eatables of rural areas. Journal of Food

Science and Technology, 22, 269272.

Khanna, S.K., Srivastava, L.P. & Singh, G.B. (1986).

Comparative usage pattern of synthetic dyes in yellow

orange coloured eatables among urban and rural

markets. Indian Food Packer, 40, 3337.

Khanna, S.K., Upreti, K.K. & Singh, G.B. (1987). A

Comparative study on the pattern and magnitude of

adulteration of food stus during two decennial survey

terms. Indian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics, 24, 310

318.

Larsen, J.C. (1991). Erythrosine toxicological evaluation of

certain food additives and contaminants. 37th meeting of

JECFA-WHO. Food Additives Series, 28, 171180.

Lockey, S.D. (1977). Hypersensitivity to tartrazine (FD & C

Yellow #5) and other dyes and additives present in food

and pharmaceutical products. Annals of Allergy, 38, 206

210.

Mathur, P. (2000). Risk Analysis of Food Adulterants.

Doctoral Thesis. Delhi: Delhi University.

NIN (1994). Studies on newer adulterants and contaminants.

Annual Report 199394 of the National Institute of Nutrition. Hyderabad: Indian Council of Medical Research.

Power, J.G.P., Barnes, R.M., Nash, W.N.C. & Robinson,

J.D. (1969). Lead poisoning in Gurkha soldiers in Hong

Kong. British Medical Journal, 3, 336337.

Prasad, O.M. & Rastogi, P.B. (1982). Eect of feeding a

commonly used non-permitted colour orange II on the

hematological values of Mus musculus. Journal of Food

Science and Technology, 19, 150153.

The Prevention of Food Adulteration Act & Rules (1995).

Pp. 1250. New Delhi: Confederation of Indian Industry.

Ranganna, S. (1986). Handbook of Analysis and Quality

Control for Fruits and Vegetable Products. Pp. 286329.

New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill.

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2004 39, 125131

2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Usage of colours in RTE foods P. R. Jonnalagadda et al.

Rao, B.S.N. (1990). Food additives consumers viewpoint.

Indian Food Industry, 9, 1419.

Sachadeva, S.M., Mani, K.V.S., Adaval, S.K., Jalpota,

Y.P., Rasela K.C. & Chadha, D.S. (1992). Acquired toxic

methaemoglobinaemia. Journal of Association of Physicians India, 40, 239240.

Sharma, I. & Sharma, S. (1994). Prevalence of Ready-to-Eat

Food Intake Among Urban School Children in Nepal and

its Impact on Nutritional Status and Behavior. Doctoral

Thesis. Delhi: Delhi University.

Singh, S. (1997). Surveillance of non-permitted food colours

in eatables. Indian Food Industry, 16, 2831.

Singh, R.L., Khanna, S.K. & Singh, G.B. (1987). Acute and

short-term toxicity studies in orange II. Veterinary

Human Toxicology, 29, 300304.

2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Sinha, A. (1988). Food additives a critical evaluation of

regulation and enforcement mechanism in India. Indian

Food Packer, 42, 5972.

Toteja, G.S., Mukherjee, A., Mittal, R. & Saxena, B.N.

(1990). ICMR Manual Methods of Analysis for Adulterants and Contaminants in Foods. Pp. 5662. New Delhi:

Indian Council of Medical Research.

Walford, J. (1984). Developments in Food Colours. Pp. 76

79. London and NewYork: Elsevier Applied Science

Publishers.

Wess, J.A. & Archer, D.C. (1982). Disparate in vivo and in

vitro immuno-modulatory activities of Rhodamine B.

Food and Chemical Toxicology, 20, 914.

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2004, 39, 125131

131

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Comparative Study On The Dahi-Prepared From Whole Milk, Skim Milk, Reconstituted Milk and Recombined MilkDocument6 pagesComparative Study On The Dahi-Prepared From Whole Milk, Skim Milk, Reconstituted Milk and Recombined MilkDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- HIDES AND SKINS: AN INTRODUCTIONDocument6 pagesHIDES AND SKINS: AN INTRODUCTIONDilip Gupta100% (1)

- 2nd Article PublicationDocument6 pages2nd Article PublicationDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Thermoregulation in PoultryDocument7 pagesThermoregulation in PoultryDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chhana Based Sweets PDFDocument13 pagesChhana Based Sweets PDFDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- MTE-01 Bachelor'S Degree Programme (BDP) C.) Term-End Examination December, 2012 Elective Course: Mathematics Mte-01: CalculusDocument8 pagesMTE-01 Bachelor'S Degree Programme (BDP) C.) Term-End Examination December, 2012 Elective Course: Mathematics Mte-01: CalculusChowdhury SujayPas encore d'évaluation

- FDA's quality control and safety standards for animal productsDocument6 pagesFDA's quality control and safety standards for animal productsDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Apf Residential Training Programme On Packaging Technology 43Document1 pageApf Residential Training Programme On Packaging Technology 43Dilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Quality Management Teaching Material - Final PDFDocument196 pagesQuality Management Teaching Material - Final PDFDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Value Added Meat ProductsDocument2 pagesValue Added Meat Productseditorveterinaryworld100% (2)

- Agricultural ExtensionDocument30 pagesAgricultural ExtensionDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sampling and Testing MilkDocument10 pagesSampling and Testing MilkDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Egg Packing, Transport, StorageDocument13 pagesEgg Packing, Transport, StorageDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Quality and Acceptability of Value-Added Beef BurgerDocument7 pagesQuality and Acceptability of Value-Added Beef BurgerDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Current Status, Constraints and Strategy For Promoting Processed Poultry Meat ProductsDocument6 pagesCurrent Status, Constraints and Strategy For Promoting Processed Poultry Meat ProductsDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Meat - Def 0801Document18 pagesMeat - Def 0801Dilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Value Added ProductsDocument5 pagesValue Added ProductsDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Crude Fat Determination - Soxhlet Method - 1998Document3 pagesCrude Fat Determination - Soxhlet Method - 1998david_stephens_29Pas encore d'évaluation

- Processing of Buffalo Meat Nuggets Utilizing Different BindersDocument7 pagesProcessing of Buffalo Meat Nuggets Utilizing Different BindersDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Antibody Engineering 1Document23 pagesAntibody Engineering 1Dilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Termination of PregnancyDocument17 pagesMedical Termination of PregnancyDilip Gupta100% (1)

- Unit 21 - Feeding ChildrenDocument8 pagesUnit 21 - Feeding ChildrenDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Lecture On Colligative Properties in An Undergraduate CurriculumDocument5 pagesA Lecture On Colligative Properties in An Undergraduate CurriculumDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Postpartum Uterine Infection in CattleDocument26 pagesPostpartum Uterine Infection in CattleDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Enzootic Bovine Leukosis Disease Causes & SignsDocument3 pagesEnzootic Bovine Leukosis Disease Causes & SignsDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- HACCP in Table Egg IndustryDocument36 pagesHACCP in Table Egg IndustryLen Villamoya Simpas100% (1)

- Meat Judging 2007 UC Davis Ag & Env Sci Field Day: High TeamsDocument4 pagesMeat Judging 2007 UC Davis Ag & Env Sci Field Day: High TeamsDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- 219 222Document4 pages219 222Dilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Revised 6/2008 Purpose and Standards: Oultry UdgingDocument5 pagesRevised 6/2008 Purpose and Standards: Oultry UdgingDilip GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Developing Public Performance IndicatorsDocument7 pagesDeveloping Public Performance IndicatorsFarai ZanamwePas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency First Response GuideDocument13 pagesEmergency First Response GuideCarl Danley100% (2)

- Accommodative Lag Using Dynamic Retinoscopy Age.10Document5 pagesAccommodative Lag Using Dynamic Retinoscopy Age.10JosepMolinsReixachPas encore d'évaluation

- A 50-Year-Old Female With Quadriparesis Secondary To Viral Myositis: Unusual Presentation and Diagnostic ApproachDocument4 pagesA 50-Year-Old Female With Quadriparesis Secondary To Viral Myositis: Unusual Presentation and Diagnostic ApproachInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bioidentical Hormone TherapyDocument8 pagesBioidentical Hormone TherapyKorry Meliana PangaribuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Notarte CaseDocument5 pagesNotarte CaseGenesis NioganPas encore d'évaluation

- Peak Fitness WorkoutDocument6 pagesPeak Fitness WorkoutIsael AlemanPas encore d'évaluation

- 55122505241#5852#55122505241#9 - 16 - 2022 12 - 00 - 00 AmDocument2 pages55122505241#5852#55122505241#9 - 16 - 2022 12 - 00 - 00 AmAdham ZidanPas encore d'évaluation

- Irc Hazid SSDocument2 pagesIrc Hazid SSSayed RedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bridget Yvette Hughes Non-Disciplinary Order With The Texas Board of NursingDocument8 pagesBridget Yvette Hughes Non-Disciplinary Order With The Texas Board of NursingShirley Pigott MDPas encore d'évaluation

- Ace Personal Trainer Chapter 3Document45 pagesAce Personal Trainer Chapter 3Daan van der Meulen100% (2)

- 017 Incident or Near Miss ReportDocument19 pages017 Incident or Near Miss Reportimranul haqPas encore d'évaluation

- Glaxo SmithKlineDocument4 pagesGlaxo SmithKlineRRSPas encore d'évaluation

- Formulating A Dental Treatment Plan: DR Tashnim BagusDocument33 pagesFormulating A Dental Treatment Plan: DR Tashnim BagustarekrabiPas encore d'évaluation

- Commensal AmebaeDocument11 pagesCommensal AmebaeGladys Mary MarianPas encore d'évaluation

- Lisinopril, TAB: Generic Name of Medication: Brand/trade Name of MedicationDocument6 pagesLisinopril, TAB: Generic Name of Medication: Brand/trade Name of MedicationCliff by the seaPas encore d'évaluation

- Neonatal Incubator en B8B6 V1.2Document8 pagesNeonatal Incubator en B8B6 V1.2Surta DevianaPas encore d'évaluation

- EM Basic Chest Pain: Pet Mac P E T M A CDocument7 pagesEM Basic Chest Pain: Pet Mac P E T M A CAkanksha VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- NCPDocument5 pagesNCPSheana TmplPas encore d'évaluation

- Makalah: Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Kesehatan (Stikes) Maluku Husada AmbonDocument24 pagesMakalah: Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Kesehatan (Stikes) Maluku Husada AmbonAngel ViolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal KesehatanDocument11 pagesJurnal KesehatanAfifah Nurul HidayahPas encore d'évaluation

- Evaluate Hazards and RisksDocument17 pagesEvaluate Hazards and RisksJENEFER REYESPas encore d'évaluation

- DrugsDocument2 pagesDrugsJan PatrickPas encore d'évaluation

- Accessibility To Potable Water Supply and Satisfaction of Urban Residents in Lokoja, NigeriaDocument20 pagesAccessibility To Potable Water Supply and Satisfaction of Urban Residents in Lokoja, NigeriaGovernance and Society ReviewPas encore d'évaluation

- 0D Zinc Oxide NanoparticlesDocument8 pages0D Zinc Oxide NanoparticlesKevinSanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Obstetrical Nursing, Trinidad IgnacioDocument26 pagesObstetrical Nursing, Trinidad IgnaciojeshemaPas encore d'évaluation

- SORIANO, Angelica Joan M. - NURSING CARE PLAN Activity 2. NCM 114Document5 pagesSORIANO, Angelica Joan M. - NURSING CARE PLAN Activity 2. NCM 114Angelica Joan SorianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis Pareto - VENDocument6 pagesAnalisis Pareto - VENrohani panjaitanPas encore d'évaluation

- Green Playful Welcome Back To School NewsletterDocument16 pagesGreen Playful Welcome Back To School NewsletterJocelyn RoxasPas encore d'évaluation

- COVID-19 Pandemic, Socioeconomic Crisis and Human Stress inDocument12 pagesCOVID-19 Pandemic, Socioeconomic Crisis and Human Stress inMaisha Tabassum AnimaPas encore d'évaluation